15 minute read

Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce 2017 Annual Magazine

YOU CAN’T “BEAT L.A.!” NOT WHEN IT COMES TO SPORTS.

Sports play an important role in the fabric of L.A. as a source of fan appreciation and the driver of a multibillion dollar industry.

BY JIM FARBER

Rarely has a single day changed the profile of a city more than April 18, 1958 did for Los Angeles. On April 17, L.A. was a minor outpost in the world of sports, a continent away from where the real action was.

Yes, there was a professional football team, the Rams. The City had hosted the Olympics in 1932. There was minor league baseball and horse racing, as well as the occasional pro golf and tennis tournament. There was pro wrestling (if you consider that a sport, remember Gorgeous George?). There was boxing and roller derby and the slam-bam entertainment of demolition derby.

The real exception was in college sports, driven by the greatest cross-town rivalry in the country, which ignited any time UCLA and USC squared off. And once a year, there was the glory of the Rose Bowl game. But no one really thought of L.A. as a sports empire, and the first chant of BEAT LA was a long way off.

Then, on April 18, 1958, it all changed.

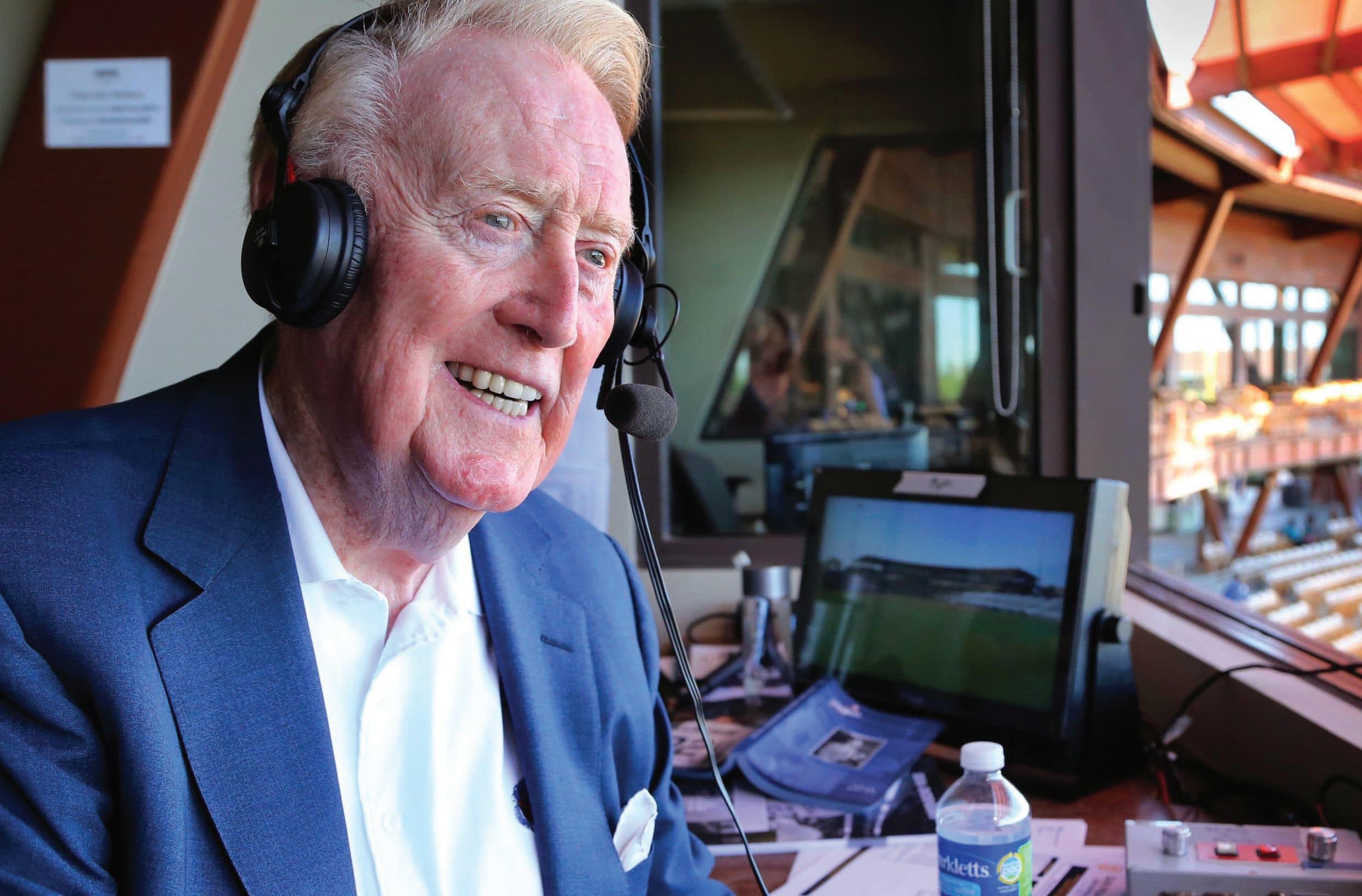

The former Brooklyn Dodgers played their first game as the Los Angeles Dodgers on a makeshift field at the Coliseum, defeating their National League rivals, the Giants, 6-5 before a crowd of 78,672. That game put L.A. on the national sports map. It also introduced baseball fans to the voice of Vincent Edward “Vin” Scully, who was destined to become as beloved by the City as the team itself.

It’s interesting, though, to imagine what the conversations in the Brooklyn Dodger clubhouse must have been like prior to the big move. The team had roots in the New York borough that went back to 1890! They’d played 62 seasons as a professional baseball team, had their name changed from the Bridegrooms to the Trolley Dodgers to simply the Dodgers. They’d also acquired a scruffy nickname, “Dem Bums!” Their fans loved them, especially when they went up against and beat their dreaded nemesis, the New York Yankees. They would be leaving the greatest sports city in the country and heading 3,000 miles

west essentially because the city fathers of Brooklyn refused to pony up the money to build a new ballpark. Sound familiar?

A few of the players, like Duke Snider, who was born in L.A., and Jackie Robinson, who had been a star at UCLA, knew what lay in store. But for most of the team, Walter O’Malley’s cross-country adventure meant a betrayal of their fans and the uprooting their families for who knows what?

That first season O’Malley made a tactical/marketing decision to stay with old guard players like Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Gil Hodges and Clem Labine, mainly because he felt they symbolized the Dodger brand. It proved to be a bad idea and the team finished in last place. But the next season, driven by a corps of young players, including a pair of fireballers named Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, the team captured its first championship as the Los Angeles Dodgers!

In the years that followed the Minneapolis Lakers became the Los Angeles Lakers; the San Diego Clippers became the LA Clippers; and the former minor league Angels became the Los Angeles Angels of the American League. Professional hockey, soccer, women’s basketball and Grand Prix auto racing also joined the roster.

If there was a golden era, it had to be the 1960s. UCLA was winning basketball titles. USC was consistently in the Rose Bowl.

The Dodgers were in the World Series. The Lakers were on top of the NBA. And the chant, BEAT L.A., became something to be proud of. Other titles followed. The Kings would take the Stanley Cup and the Sparks would become the premier team in women’s professional basketball.

In 2012, a study conducted by the L.A.

Sports Council and the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce calculated the combined impact of sports (collegiate and professional) on the economy of L.A. had reached a level of $4.1 billion!

As the report stated, Using data obtained confidentially from 50 local sports organizations (the survey

excludes high school sports and certain special one-time events) the study compiled and evaluated aggregate annual revenue, employment and attendance figures for the calendar year 2012.

“The sports industry stimulates economic development, contributes to workforce development and enhances the sense of

community. This study validates a fact that we already know to be true … L.A. is a great sports town and will continue to be one,” said Alan Rothenberg, chairman of both the Sports Council and the Chamber. This the first study in three years and the eighth overall in a series dating back to 1993. It is the most comprehensive of its kind for the L.A. region.

The survey included professional franchises, sports venues, horseracing tracks, major colleges and universities, as well as annual recurring events such as the L.A. Marathon, the Long Beach Grand Prix and the Rose Bowl Game.

According to the results, sports pumped $1.7 billion directly into the local

economy last year, which, after factoring in the customary economic multiplier provided by a federal government agency, translates into an overall gross economic impact of $4.1 billion. The weighted multiplier of 2.47 was derived from data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and was used to quantify the ripple effect that consumer spending

within the sporting events industry has on the overall regional economy.

The report, according to David Simon, current president of the L.A. Sports Council, only focused on a specific segment of the overall impact of sports. It did not take into account, as Simon points out, revenue produced from the sale of television rights and team related

THE SUCCESS OF AN OWNER IS JUDGED NOT NECESSARILY BY THE PERFORMANCE OF A TEAM ON THE FIELD, BUT BY THE VALUE OF THE FRANCHISE.”

manufacturing. It did not focus on the vast employment network directly related to sports: from coaches, players and administrators, to the business of sports management, sports medicine and most recently sports analytics. It’s like a pyramid that reaches from the owners at the top down to the level of the grounds staff, ticket takers and concessionaires.

“$4.1 billion dollars is a significant amount of money,” Simon emphasizes. “But if you take into account all the related employment and services, the number is substantially higher. And that report was compiled in 2012!”

While the economic impact sports bring to L.A. is substantial, Simon emphasizes that sports also has a direct impact on the City’s psyche — fans identify with teams, whether they bleed Dodger-blue, are part of Clipper Nation, or shout “Go Bruins!” “Go Trojans!”

“There is an incredible amount of money in sports today that just wasn’t there 50 years ago,” Simon observes. “From the time Donald Sterling bought the Clippers for $12 million, the team’s value increased 100 times! That’s why a premier L.A. franchise like the Dodgers can attract high level investors like Magic Johnson. The success of an owner is judged not necessarily by

the performance of a team on the field, but by the value of the franchise.”

Another important aspect of sports in L.A. has been the growth of diversity in the city’s population, which has allowed new sports, particularly professional soccer, to thrive by focusing ticket sales toward a specific community’s interest.

“It’s harder now, with so many teams, to command the City’s attention,” Simon points out. “But if you can command the attention of your fans, even if they only represent 10 percent of the overall community, you can be very successful financially.”

FOOTBALL COMES AND GOES AND COMES AGAIN

Professional football came to L.A. in 1946 when, after a contentious battle between the NFL and team owner, Dan Reeves, the Cleveland Rams headed west to become L.A.’s first professional team franchise. The Rams’ play-by-play announcer from 1937 through 1965 was Robert J. “Bob” Kelley,

known as “The Voice of the Rams.” He was the first in a line of star commentators of L.A. sports that would include Chick Hearn as “the voice of the Lakers,” and Vin Scully as “the voice of the Dodgers.”

From 1949-1955 (during the pre Super Bowl era) the Rams were in the NFL’s championship game four times led by quarterbacks Bob Waterfield and Norm Van Brocklin, along with a wild-running wide receiver nicknamed Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsh. During the 1960s it was the “Fearsome Foursome” that led the way: Rosey Grier, Merlin Olsen, Deacon Jones and Lamar Lundy. The team made it to the Super Bowl once, in 1979, where they lost a closely competitive game (until the fourth quarter) to the Pittsburgh Steelers.

The Rams departure from L.A. technically began in 1980, when Georgia Frontiere, who had inherited the team following the death of her husband, Carrol Rosenbloom, decided to move to the team to Anaheim. In 1995, following a succession of costly losing seasons,

Frontiere moved the team to Saint Louis where they would remain until 2016.

During the interim, from 1982-1994, L.A. had its strange love/hate affair with Al Davis and the Oakland Raiders who became the Los Angeles Raiders, only to abandon the city to again become the Oakland Raiders. It ended badly and left L.A. without an NFL franchise for the next 20 years.

Finally, after an endless succession of fits and starts and new stadium proposals, L.A. was reunited with the Rams, who played their first home game at the Coliseum on Sept. 18, 2016. But the real Rams story is still to unfold as L.A. awaits the construction of the new $2.66 billion City of Champions Stadium and Entertainment in Inglewood scheduled to open in August 2019 and host the Super Bowl in 2021.

The 298-acre project (projected to be roughly three times the size of Disneyland) is being driven by Rams’ owner Stan Kroenke who spearheaded the team’s move and the project, which in addition to its 80,000-seat stadium, will include a new entertainment complex with 8.5 million square feet of office tower space, a 6,000-seat music and theatre venue, ballrooms, a multiplex movie theatre, a lake, luxury hotels, highscale dining and a NFL Flagship Campus. Other potential uses for

the sites that have been suggested include the NCAA men’s basketball finals, the FIFA World Cup finals, the World Figure Skating Championships and a site for multiple events of the (proposed) 2024 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

“Los Angeles is built to host the Super Bowl,” City of L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti said in a statement. “We helped forge this great American tradition as its very first host in 1967 and now, at long last, we’re

bringing it back where it belongs. L.A. is already welcoming a record number of visitors from around the world and Super Bowl LV will bring even more economic prosperity to our region.”

Then on Jan. 10, the San Diego Chargers announced they were going to leave their long-time home and join the Rams as L.A.’s second NFL franchise. Eventually the two teams will share the new stadium.

But until then, the new Los Angeles

Chargers (that’s going to take some getting used to) will play their games at the Stub Hub stadium in Carson.

GOING FOR THE GOLD

On July 30, 1932, the Olympic torch entered the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and signaled the beginning of the 10th games of the modern era. It was by far the biggest sporting event in the City’s brief sports history. Ironically, L.A. had been the only

city to bid for the games. There were 117 events representing 14 different sports. Babe Didrikson won gold in the javelin and the hurdles. Buster Crabe (who would later play Flash Gordon) won the 400 meter men’s freestyle.

In 1984, the games returned to L.A. in a manner that will never be forgotten by those that competed and those that

attended the competition. It was also the first time an Olympic Games, under the direction of Peter Ueberroth, ended not with a deficit, but with a substantial surplus! Now, L.A. is actively lobbying to be awarded the 2024 games, a decision that will be announced at the conclusion of the Olympic Committee’s meeting in Lima, Peru, next September.

According to a survey conducted by Loyola University in February 2016, 88 percent of Angelenos polled said they were in favor of the games returning to the city. One of the strengths behind the L.A. bid, according to Mayor Garcetti, is the existing availability of sports

venues and other needed facilities. L.A., the mayor has said, will not require the level of construction that Paris will face. President Trump also offered his support for the Los Angeles Olympic bid in a phone conversation with Mayor Garcetti that took place in November 2016. Another strength of the Olympic bid the proposal committee has said, is based on a number of transportation infrastructure projects that will help move people to and from the games — to the point that they are dubbing 2024 the “car-free Olympics.”

According to David Simon, the L.A. Sports Council is trying to help the Olympic bid by attracting competitions in Olympic sports to L.A. leading up to 2024. They include: the World Cup of Modern Pentathlon, a world fencing competition to be held in Long Beach in 2017, the World Baseball Classic in March, and an international cycling event.

RAH! RAH! RAH! STAND UP AND CHEER FOR COLLEGE SPORTS

According to UCLA’s Athletic Director, Dan Guerrero, “When you talk about college sports on a general basis, there are more than 1000 academic institutions that have an economic impact on their specific community. There are smaller communities where the college or university represents the primary source of entertainment. But when you’re talking about a city like L.A., so many other factors come into play.”

In fact, it’s hard to think about college sports in L.A. without taking into account the starring role played by UCLA and USC.

“The impact on the community from a university athletic program like UCLA or USC’s can be significant in a number of ways,” Guerrero observes. “It contributes to the vibrancy and pride of the community; it brings in revenue and it enhances the tax base because of the dollars these programs generate.”

By far the two greatest revenue drivers are the men’s football and basketball programs.

“At UCLA,” Guerrero says, “football and basketball account for about a third of a $100 million dollar budget. Factor in television contracts and that number goes even higher. Those funds then go to support other sports programs. At UCLA, we field 25 teams, 11 men’s and 15 women’s. Our program employs 100-150 full time employees. But when you factor in facility operations and the staff for all the games, that number more than doubles.

WE ARE VERY FORTUNATE IN LOS ANGELES TO HAVE TWO MARQUEE UNIVERSITY ATHLETIC PROGRAMS THAT ARE A MERE 12 MILES APART. THERE IS NO OTHER CITY IN THE COUNTRY THAT CAN BOAST TWO PROGRAMS OF THE MAGNITUDE AND SUCCESS RATE

We are very fortunate in L.A. to have two marquee university athletic programs that are a mere 12 miles apart. There is no other city in the country that can boast two programs of the magnitude and success rate (calculated in NCAA championships) that one finds in Los Angeles.

“Athletic programs also contribute greatly to the branding of a university,” Guerrero stresses. “It has definitely helped enhance our brand at UCLA, not just nationally, but around the world.”

TITLE IX

On Feb. 28, 1972, senator Birch Bayh of Indiana added an amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965 that was up for renewal. His amendment became known simply as Title 9. Bayh pointed

out that women were not given the opportunities that men were. Men were the ones given academic opportunities such as scholarships and funding while women were not viewed as equal. Only 1 percent of the athletic budgets went to female sports at the college level. On the high school level, male athletes outnumbered female athletes 12.5 to 1. After the adoption of Title IX, which became law on June 23, 1972, there was a 600 percent increase in the number of women playing college sports. “It was all about balance, fairness, and equality,” the Indiana senator told his colleagues. “Everyone was to be treated the same no matter what.”

The statue mandated equality for the

funding of men’s and women’s sports in 10 areas.

1. Whether the selection of sports and levels of competition effectively accommodate the interests and abilities of members of both sexes.

2. The provision of equipment and supplies.

3. Scheduling of games and practice time.

4. Travel and per diem allowance.

5. Opportunity to receive coaching and academic tutoring on mathematics only.

6. Assignment and compensation of coaches and tutors.

8. Provision of medical and training facilities and services.

9. Provision of housing and dining facilities and services.

10. Publicity.

Did it work?

“Well,” says Guerrero with a laugh, “In Rio the women won considerably more medals than the men. That’s at least partially attributable to the impact of Title IX.”

Looking ahead, no one can say exactly what the future holds. But it certainly looks bright for sports as a major component of the L.A. economy and lifestyle.