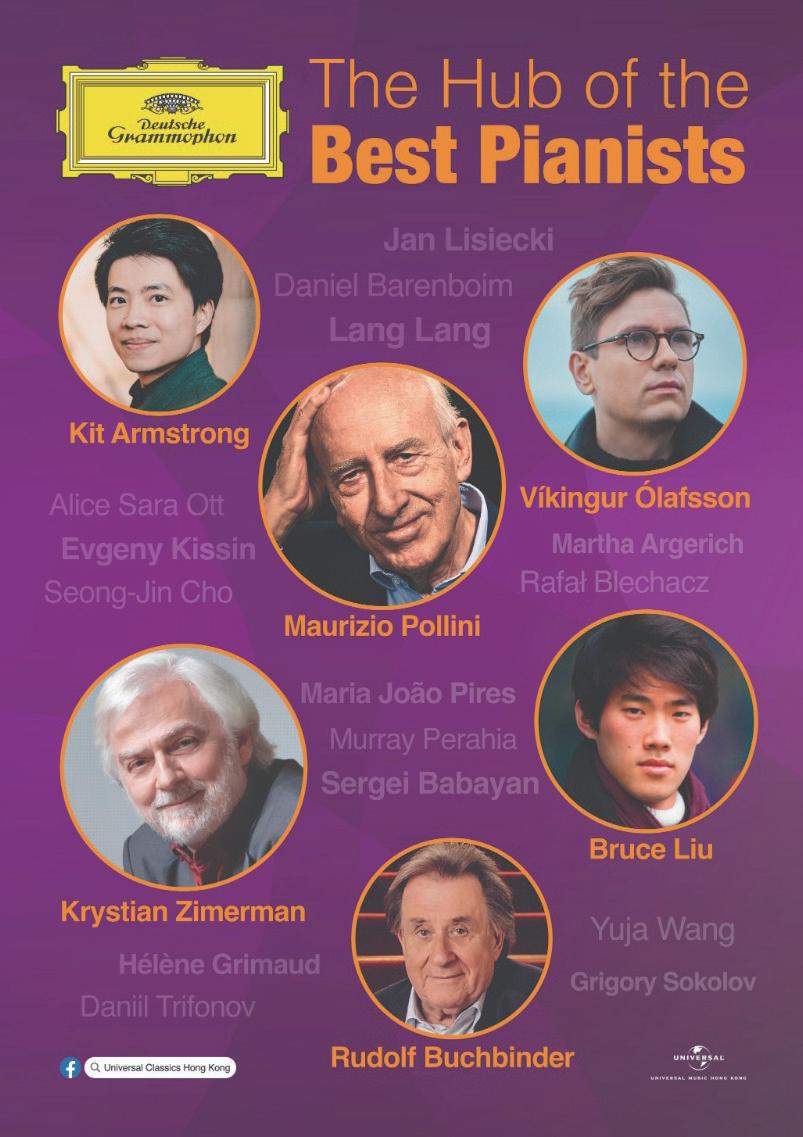

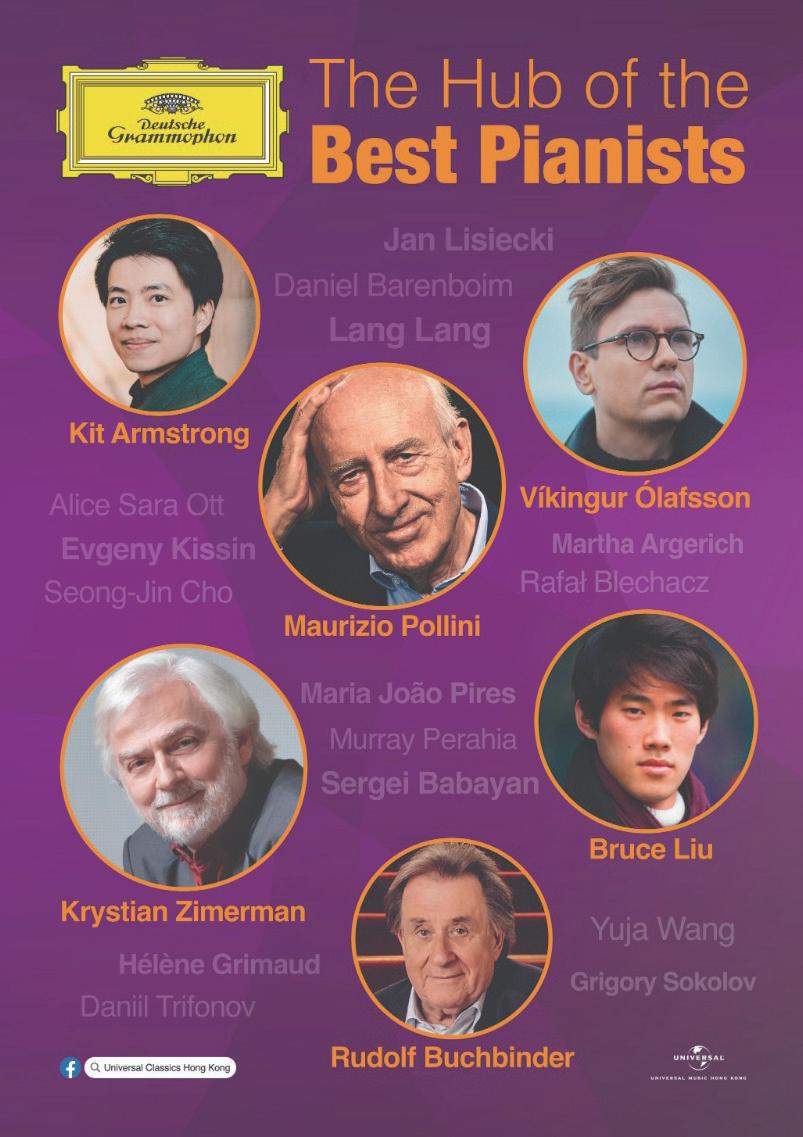

KIT ARMSTRONG

Ever since Kit Armstrong entered the international music stage twenty years ago, his activities have exerted an enduring fascination upon music lovers. Today he maintains an active career as pianist, composer, and organist. He performs as a soloist in major international venues such as the Berlin Philharmonie, Vienna Musikverein, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, and Suntory Hall Tokyo, and appears with some of the world's finest orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic, Dresden Staatskapelle, NHK Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields.

A passionate chamber musician, Armstrong has developed close artistic partnerships with other leading instrumental and vocal artists. The complete Mozart sonatas for piano and violin with Renaud Capuçon have featured at the Salzburg Mozartwoche Festival and Berlin's Boulez Hall. Armstrong has given song recitals with Benjamin Appl, Julian Prégardien, and others. Recent European tours with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra and Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, one of the world's leading early music ensembles, reflect longstanding collaborations. Armstrong has appeared as an organ recitalist at the Berlin Philharmonie, Vienna Konzerthaus, Philharmonie de Luxembourg, Weiwuying in Kaohsiung, as well as in cathedrals throughout Europe.

At the age of 5, Armstrong came to classical music through composition, and has developed a broad oeuvre of solo, vocal, chamber, and symphonic works. Edition Peters publishes Armstrong's compositions, which have been commissioned by the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Schubertiade, Bachwoche Ansbach, and Klavierfestival Ruhr among others.

Armstrong has held artist-in-residence appointments offering a wide spectrum of musical formats, combining activities as composer, pianist, conductor, and organist, at institutions including the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, the Mozartfest Würzburg, the Festspiele MecklenburgVorpommern, the Musikkollegium Winterthur, and coming up in 2023, the Museumsgesellschaft Frankfurt.

2

BIOGRAPHY

Armstrong's solo piano albums include Bach, Ligeti, Armstrong and Liszt: Symphonic Scenes, both released by Sony Classical, as well as various live recitals on DVD, including Bach's Goldberg Variations and Its Predecessors at the Concertgebouw Amsterdam (Unitel, 2017) and Wagner - Liszt - Mozart at the Bayreuth Margravial Opera House (C-Major, 2019). In 2021 Deutsche Grammophon released a double CD dedicated to a panorama of works by William Byrd and John Bull: The Visionaries of Piano Music.

Born in 1992 in Los Angeles, Armstrong started studying composition at Chapman University and physics at California State University, later chemistry and mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania and mathematics at Imperial College London. He earned a bachelor's degree in music at the Royal Academy of Music in London and a master's degree in pure mathematics at the University of Paris VI. Alfred Brendel has guided Armstrong as teacher and mentor since 2005. Their relationship was captured in the film Set the Piano Stool on Fire by Mark Kidel.

In 2012, Armstrong purchased the Church of Sainte-Thérèse in Hirson, France as a hall for concerts and exhibitions. This cultural centre that he created is home to interdisciplinary projects reaching a regional as well as cosmopolitan public, and has been the subject of profiles in the national and international press.

3

© Marco Borggreve

PROGRAMME NOTES

Allegro appassionato, Op. 70

CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Camille Saint-Saëns has often been a controversial figure. A child prodigy in the rank of Mozart and Mendelssohn, and later a capable musician whose command of musical materials had left even Liszt and Wagner in awe, he was not infrequently blamed for composing works that are indifferent. A popular musical dictionary of the early 20 th century stated that "no one possesses a more profound knowledge than he (Saint-Saëns) does of the secrets and resources of the art; but the creative faculty does not keep pace with the technical skill of the workman"; and it went on and described his compositions as neither "frivolous enough" nor sufficiently captivating to "take hold of the public by that sincerity and warmth of feeling." Composer Modest Mussorgsky put it even more bluntly; he spoke straight to his face with the comment "you will deceive no one with your pretty tunes!" But Saint-Saëns was actually a classicist and archconservative living in the age of later Romanticism, and he knew what he was doing. Reflecting on his own music, he concluded that "I ran after the chimera of purity of style and perfection of form."

Pianistically, Saint-Saëns upheld the doctrines of the previous eras. In his youth, he acquired his pianistic skills from Camille Stamaty—a pupil of Friedrich Kalkbrenner, the famous master of old-school pianism who once offered to train the young Chopin and was turned down. Unlike those who came from similar background but evolved to embrace "New Music", like Liszt, Saint-Saëns safeguarded his early ideals all his life. Indeed, his pianistic texture often conforms to that of the previous brilliant school of Ignaz Moscheles: brilliant, objective, and highly effective. Combined with his clever orchestration, this manner of pianistic writing created five brilliant concertos that thrilled many. But many would also argue that such pianism alone is incapable of carrying the weight of Romantic ideals. Maybe that is why Saint-Saëns retrieved from composing extended pianistic compositions for solo piano, such as sonatas; instead, he focused on smaller salon pieces that are perfect match to his pianistic textures. Allegro appassionato, Op. 70 is one of those pieces. Perhaps it is not unfair to say, within his self-imposed limitation he was a master in his own right.

Allegro appassionato opens with a bold statement of three notes: the first two ascending in steps, and the third falling almost shockingly to a minorsixth below—lodging on an unresolved leading note. Unyielding, this bold

4

statement recurs immediately, then again and again, often in faster tempi. Brilliant passageworks are set against this recuring three-note motive from time to time, creating both a sense of harmony and some moments of conflict. Not unlike the case in Saint-Saëns's other pianistic works, brilliant passageworks in Allegro Appassionato tend to employ few hidden melodic lines. The piece features an extended middle section, which combines the previous three-note motive with new materials in a free manner. This piece also appears in a version for piano and orchestra.

Piano Sonata No. 11 in A major, K. 331

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791)

The Piano Sonata No. 11 in A major, K. 331 is one of Mozart's best known pianistic works. Its last movement, the 'Turkish March', is often performed on its own. This work demonstrates Mozart's mastery of musical forms and pianistic textures, and it showcases his ability to bend musical elements to his will.

The composition date of this sonata is disputable. For years, it was a general belief that Mozart composed this sonata in Paris in the summer of 1778, along with two other piano sonatas, K. 330 in C and K. 332 in F. Even Ludwig von Köchel, whose Mozart catalogue we still use today, assigned the Sonata to this period. But based on more recent discoveries connected to Mozart's changing handwriting, watermarks, and the paper he used for notation, many have concluded that the piece was most likely originated from a later time, between 1781 and 1783. The importance of this controversy in dating is that Mozart was under drastically different circumstances in those two periods. If the newer estimate (which is becoming the generally accepted assumption) is indeed true, Mozart might even have composed K. 332, as pedagogical material.

At first glance, this sonata looks almost typical, almost like a standard "fast-slowfast" sonata. Indeed, it has three movements, including a fast and rhythmic finale. But a closer look reveals something less predictable. None of the three movements is in the so-called "sonata form." The first movement is a set of variations based on a graceful theme, whose subsequent variations—while exploring various musical possibilities through a systematic incorporation of multiple devices—look more like a display of compositional options than an attempt to create drama that is typical in the opening movements of Mozart's sonatas. The middle movement, normally the slowest of the three movements (an arrangement that highlights the standard "fast-slow-fast" construction), is

5

actually a minuet. The 'Turkish March', as charming as it is, destabilises the tonal core of the sonata; it opens in the unusual key of tonic minor, and ventures boldly and quickly through various keys that are based on two different tonal centres. All these arrangements create a tremendous demand for a grand closure, which Mozart provided in the end. The sonata ends with a prolonged and dazzling passage that is built almost entirely on plagal and perfect cadences in the home key of A major.

The Earl of Oxford's March|The Bells WILLIAM BYRD (1540-1623)

MelancholyPavan|Fantasia

JOHN BULL (1562/63-1628)

English keyboard music from the late Renaissance to the time of Purcell was innovative and daring. A distinctive harpsichord/virginal style was gradually formed, apart from the organ style. Two of the key figures during this period of stylistic formation were William Byrd and John Bull.

Harpsichord/virginal compositions from this era appeared in many forms, including variations, dances, and fantasias. On one hand, many variations were keyboard arrangements of polyphonic vocal music armed with decorative figurations; some, on the other hand, were built on ostinati or short rhythmic patterns (instead of on pre-existing melodies). William Byrd's The Bells is an example of the latter. The piece is a set of colourful variations over an exceptionally short ground bass: only two notes, a semibreve C and a minim D, which keep alternating to depict the tolling of bells. Byrd employed complex contrapuntal lines above this bass line, presumably an attempt to keep listeners' attention throughout the composition's nine sections.

Solo keyboard dances from this period often employed compositional techniques similar to those used in variations; however, dances tended to be less solidly structured and less complicated. John Bull's Melancholy Pavan, a slow and somewhat stately dance, is an example. Fantasias, different from solo dances and variations, often based neither on existing melodies nor pre-set patterns/motives. Instead, they were frequently governed by successive points of imitation. This manner of composition is showcased in Bull's Fantasia.

6

In this era, the title of a composition might provide clues to its origin. Byrd's The Earl of Oxford's March was closely related to the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, who was Byrd's patron. The piece is military in character, filled with passages that depict drumbeats and trumpet calls. Evidently a popular work as soon as it was composed, it appeared in multiple collections of keyboard works that were widely circulated at the time.

Études de dessin

KIT ARMSTRONG (1992-)

For centuries, music and painting have been subject to aesthetic parallels and shared inspirations. When I think of painting, I see the art of drawing as not only its foundation, but its heartbeat. It was my wish in Études de dessin to translate the expression of drawing into the world of music.

Colour and texture often go together in music. This applies especially to the piano, whose potential is realised through creating acoustic illusions— that a note appears to lead to another, or that touch informs the character of a sound. It may even be the very disconnect between acoustic reality and perception that can elevate piano music to a magical experience. I am immediately reminded of ink drawings where, similarly, the dissociation from optical reality allows a paradoxical feeling of being closer to its essence.

Fundamental to both cases is the invitation to let technical details blossom, in the beholder's imagination, into sentiments. A brushstroke becomes expressive not only through such attributes as smoothness and elegance; it may project intimations of character that are so abstract and yet so personal, as only a series of tones could otherwise do.

(Programme notes by the composer)

Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach's Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue is perhaps his most celebrated stand-alone keyboard composition. The work's popularity never seems to wane despite the change in musical taste over time. It survived the age of Empfindsamkeit in the 18 th century, the several generations of 19 th century Romantics, the time of first commercial sound-recordings, and the

7

PROGRAMME NOTES

more recent "early music movement." Mendelssohn and Brahms played it. Virtuosos like Liszt and Busoni performed it—often as it is printed, without added bravura or embellishments. Generation of students learned it. Scholars studied it. As David Dubal pointed out, its "emotional content remains 'Romantic' to each generation."

In 1717, Bach was imprisoned in Weimer for a month. Upon his release, he left almost immediately for Cöthen, where he would compose many of his secular works, include the Brandenburg Concertos. It is often believed that much of Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue was also composed there. The work exists in many manuscripts. Evidently, multiple manuscripts were circulating in Bach's home, and he seemed to be altering the piece on a continuing basis, sometimes without regard to previous alterations. A logical explanation is that he was frequently preparing pedagogical drafts for the needs of individual students. The work, as we know it today, consists of a number of variants which, however, pertain to textural details and do not affect the overall shape of the piece.

The composition consists of three main sections, each of which Bach added title to: Fantasia, Recitativ, and Fuga. The Fantasia is often the focal point that commentators pay most attention to. It has been described in Art of Fugue: Bach Fugues for Keyboard, 1715-1750 as "Bach at his most Baroque, Bach at his most extravagant, untrammeled, physical, in your face." It has a short but almost furious opening, followed by an unending stream of tonally and rhythmically unstable figurations, before two elaborated sets of half-notated arpeggiations take over. The Recitative has attracted slightly less attention, but it is not any less remarkable. It features a constant fluctuation of mood; chromatic and delicate monophonic lines alternate repeatedly with dissonant chords in close position, creating a persisting sense of unresolved tension. The fugue is different from many fugues in The Well-Tempered Clavier in the sense that it is for display and not education. As a result, refined details would give way to spontaneous effects, and sense of balance to calculated asymmetry. In this fugue, contrapuntal tools such as stretto are absent; meanwhile, the fugal subject is not only ambiguous in both tonality and phrasal structure, but also subjected to a great deal of variation when it recurs.

8

Variations on the Cantata Weinen,Klagen,Sorgen,Zagen (after J.S. Bach)

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, Lamenting, Tormenting, Despairing) is Liszt's relatively unknown work; it is a set of intense variations based on a chromatic bass progression borrowed from Johann Sebastian Bach's cantata, BWV 12. Apparently, Liszt employed chromaticism in a much more radical way than Bach did. Bach always preserved a clear sense of tonality; Liszt, however, allowed tonal identity to simply fade away, showing a path towards its total absence. Some found this work puzzling, including The New York Times critic Harold C. Schoenberg, who considered it "hard to describe as Liszt himself, for it is a combination of nobility and sentimentality, poetry and vulgar effects."

Almost fifteen years after he retired from the stage, Liszt was a different man when he composed this work. The work is dark, bearing little resemblance to the showpieces that once made him a popular icon. On the contrary, it is sometimes reminiscent of the darker passages in his Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata, which depicts scenes beyond life. Composed in 1862, the piece was probably connected to the death of Liszt's two children with Countess Marie d'Agoult: Blandine-Rachel and Daniel. His last remaining child with the Countess Cosima, would later marry Richard Wagner.

The work opens with an intense introduction that features a series of ascending chromatic octaves in the bass line, creating a mood corresponding to the work's title. When Bach's bass line is introduced, it is first accompanied by a short and syncopated counter-motive, which is then replaced by consecutive intervals in sixth. Next, pianistic devices common in Liszt's previous compositions—chord-streams with alternating hands, marcato melodies accompanied by dazzling repeated notes, virtuosic octaves, broken chords with wide skips—are adopted one by one, bringing the piece to a climax. Approaching the end, a recitative marked lagrimoso (tearful) takes over, gradually blurring any sense of tonality. The final section incorporates the hymn tune Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan (What God Ordains Is Always Good), which receives a tonal treatment.

PhD in Musicology, HKU

9

Programme notes by Chung-Kei Edmund Cheng

10 H K U

www.muse.hku.hk

PRESENTED BY FOLLOW US

SUPPORTED BY HKU MUSE

© Marco Borggreve

PRESENTED BY FOLLOW US

SUPPORTED BY HKU MUSE

© Marco Borggreve