7 minute read

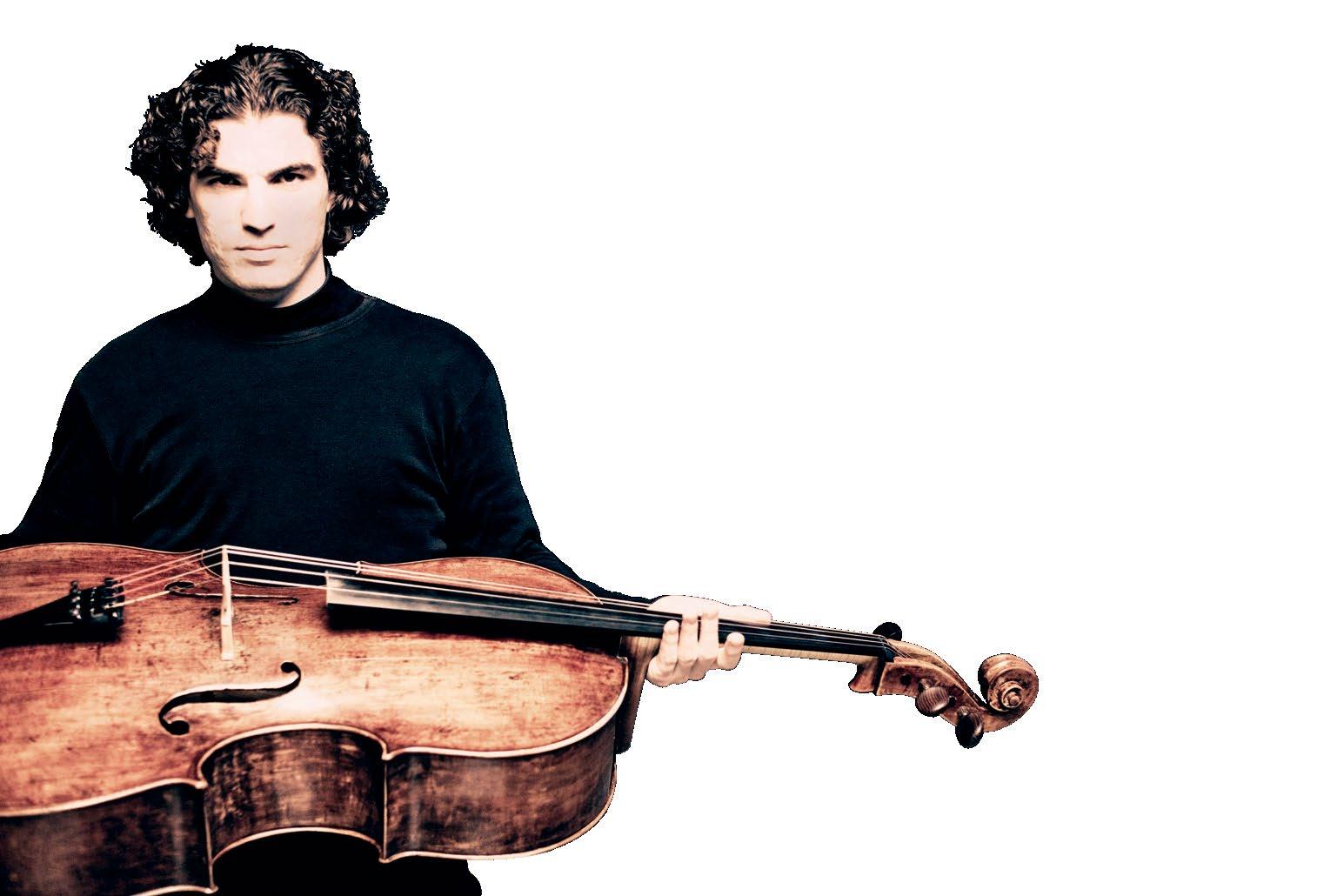

Human, all too human Paul Lewis

25 October 2022

With Schubert, I started on the dark side. The first sonata I played as a teenager was the A minor D. 784. It's one of his pivotal sonatas, written around the time he got his syphilis diagnosis. In the wake of that death sentence, everything became bleak. That's the core of his message. The change of his style and musical language was immediate and shocking. That was my introduction to Schubert— I didn't start with the cosy, early music—so he has always been essentially a dark composer for me.

Advertisement

I've always been struck by his lack of answers. With Beethoven, there are questions, but he almost always creates some sense of resolution. That's rarely the case with Schubert. And yet there's also a sense of hope. For me, that makes him the most human of all composers—especially now, when we don't have answers to very much.

'There are so many things going on and the challenge is to control these and achieve the balance you're looking for'

His music has so many layers of emotion—the surface ones, but many others just beneath that. It's the same with the piano writing—there are so many things going on and the challenge is to control these and achieve the balance you're looking for. His writing can be quite awkward and not very pianistic. There's a famous story that he had his friends round and tried to play the Wanderer Fantasy but broke down, gave up and said, "Let the devil play it." I don't think he necessarily had the ability to play to the level of technical difficulty of his music, but I imagine he had a fantastic ability to control levels of pianissimo, with a high level of touch control.

With Schubert, more than with any other composer, the condition of the piano is crucial. You need an instrument that will help you play infinite levels of pianissimo. You want to go down to an almost imperceptible volume, but to keep the core of the sound—a whisper that somehow gets to the back of the hall. It's difficult to achieve that with a piano that's set up to be powerful and bright, for playing Rachmaninov in a 3,000-seat hall. You need something more subtle, with an even left pedal voicing that allows you to play incredibly softly, without skating on the surface of the keys. You have to play into the keys, pressing them down very slowly but with the notes still sounding. That depends on how the action has been set up. For my recording I used a Steinway Model D in Flagey, and Thomas Hübsch, the Berlin Philharmonie's piano technician, spent a day working on it.

'You're dealing with tiny gradations of sound, colour and character, but they're so significant. They set up the whole character of a piece'

Alfred Brendel was a huge influence in my understanding of Schubert. When I played to him in the 1990s, he opened new doors in terms of how to think about this music. His lessons are still vivid, even at this point. I'm not sure how much I took on board immediately, but these things take time to process and to translate into your own musical thinking and language. I remember playing him the G major Sonata D. 894. We spent a lot of time balancing the opening—you can do that endlessly, balancing the chords, colouring each individual voice. You're dealing with tiny gradations of sound, colour and character, but they're so significant. They set up the whole character of a piece.

The sonatas on this CD [Schubert: Piano Sonatas, D. 537, 568, 664] are all earlyish works. The A minor D. 537 is a precursor to the later A minor sonatas. It doesn't have the sense of distress or bleakness or even anger of those, but all the ingredients are there. It's interesting that the slow movement theme is the same he uses in the last movement of the great A major D. 959. Obviously, this was a theme that meant something to him. It has the sense of intimacy and introspection that you instantly recognise as being Schubert. It's hard to define what that is, though—maybe it's a sense that it doesn't project itself out to you but draws you in.

The E-flat sonata D. 568 is an incredibly beautiful, lyrical piece. It doesn't have the storm clouds or the particular depth you have in the later sonatas, but it's a big piece, on a grand scale, and it has all the ingredients of what would become dark in his music later on. There's a sense of longing, "sehnsucht", which turned into something a little bit more desperate later on, but is merely nostalgic in the early pieces.

The "little" A major D. 664 is probably one of his best-known sonatas. I played it 20 years ago when I did my last sonata series and haven't played it since. Back then, it was my least favorite Schubert Sonata, probably because it's so popular and I didn't see the depth in it. Coming back to it, I see what I missed first time around—it is a pleasure to play.

It's 20 years since I gave my first Schubert series, and everything is different, somehow. When you come back to something you haven't played for a long time, you see things in a different way, in a different balance. When you let music rest and live your life, experiencing things and playing other music, it all feeds in and influences your interpretation. When I played these sonatas 20 years ago at the Wigmore Hall, we recorded them for posterity. There are some good things in these recordings, but from this perspective, aged 50, looking back to 30-year-old me, I hear a blandness. At this point in my life, I see so much more detail in the music, including the richness of the expressive detail that perhaps I missed 20 years ago.

Maybe that's the learning process. When I study a new piece these days, it takes much longer than it did all those years ago. I remember learning Liszt's Dante Sonata when I was 15 and playing it in a concert two weeks later. That's not long to get under the notes. I have a recording of my performance and, of course, there's so much missing in terms of expression and detail. When you're younger, you're at the start of that learning process, and it takes a lifetime to get under the skin of these great works. There are endless possibilities to unearth and it simply takes time.

'Performing a series is an indulgence. It's a chance to spend lots of time with music that you love'

Performing a series is an indulgence. It's a chance to spend lots of time with music that you love. People talk about series being definitive, but I don't think that's ever the case. It is always just a particular journey within the output of a composer's work. Schubert piano sonatas show us so many things, many of which are fundamental to what he expresses, but it can't be everything because it lacks the human voice, which is probably the most fundamental part of Schubert's work. You have to know his songs intimately and to bring that knowledge, because there are so many cross-references, so many ways that the lieder and the sound of the human voice feed into his piano sonatas.

Even across a series, my interpretations change a lot. The piano is a big factor, as well as the hall—subconsciously, you're always adapting to what you're hearing and the feedback. Every time I play a concert, I treat it as a lesson. I go back the next day and think it all through wondering, "What can I do to improve this?" You comb through everything and try to be your own best teacher. It's always changing. Every concert experience is a step in the process.

© 2022 Paul Lewis

HKU MUSE 10 Years

In the last 10 years, MUSE has amused, bemuse and confused the standard practices in concert presentations, bringing new ideas and energies to the cultural offering in Hong Kong. In doing so, it has raised the University as a major force in cultural leadership, and as a cultural hub for the HKU community and friends. Most of all, MUSE has been a muse for many: inspiring us to explore, create, and think more deeply. MUSE has made the Grand Hall, with its astounding acoustics, a cultural home, a cultural lab, and a living room that lives and breathes live music anew. There are

‧ MANY DEBUTS, such as Berliner Barock Solisten, Khatia Buniatishvili, Jeremy Denk, LENK Quartet, Yunchan Lim, Jan Lisiecki, NOĒMA, Nobuyuki Tsujii, Zhu Xiao-mei;

· MANY FIRSTS, such as the release of Beethoven 32 Sonatas Vinyl and CD boxsets with Alpha Classics, the publishing of In Time with the Late Style book with Oxford University Press, and the launch of Around Twilight LectureDemonstration and the Music in Words podcasts;

· MANY RETURNING STARS, such as Angela Hewitt, Paul Lewis, Konstantin Lifschitz, Jean Rondeau, and Takács Quartet;

· MANY NEW WORKS by HKU composers, such as David Chan, Owen Ho, Anthony Leung, Peter Tang, Kiko Shao, and Jing Wang;

· MANY STUDENT ENGAGEMENTS, such as writing programme notes, performing alongside professional musicians, and gaining practical art administration experience;

· MANY IN-DEPTH EXPLORATIONS on monumental works, such as the complete cycle of Beethoven Violin Sonatas, Bartók String Quartets, Bach Well-Tempered Clavier, Schubert Piano Sonatas, and Schubert Song Cycles;

And, most importantly, there are many collaborations and amazing moments that will always be treasured by our audiences. What's your unforgettable MUSE moment? That's why we are here—to make the invaluable possible. So as we celebrate our 10 th anniversary, be a muse for us in whatever way you can to encourage MUSE for years to come.

於2013年啟用的李兆基會議中心大會堂是港大百週年校園的亮點建築,原址為 水務署的配水庫,服務港島各區超過半世紀。「繆思樂季」與大會堂同步誕生, 致力令這個具備美妙音響效果的場地成為普羅大眾樂意踏足,並不時流連忘返的 「知識庫」。

「繆思樂季」起步之初即另闢蹊徑,朱曉玫的《哥德堡變奏曲》(2014)、呂培原的琵 琶古琴演奏會(2014),至今仍為樂迷津津樂道。往後列夫席茲的貝多芬鋼琴奏鳴曲 全集(2017)、休伊特的巴赫平均律鍵盤曲集(2018)、以及近年塔克斯四重奏的巴爾 托克全集(2019),均開風氣之先,提供現場聽全某一整卷音樂經典的機會,一新觀 眾耳目。其中,列夫席茲八場音樂會的現場錄音,「繆思樂季」還與Alpha Classics 合作,發行了全球限量版的黑膠和鐳射唱片(2020)。

推廣知識交流是大學的使命,「繆思樂季」除了在節目策劃上與音樂系合作無間,還 不時邀請系內老師與樂手或嘉賓以對談、導賞、示範講座等形式,將相關的人文知 識一點一滴、深入淺出介紹給觀眾,冀能做到寓教於樂,與眾同樂。

但「繆思樂季」的合作對象並不囿於港大校園。樂評人如臺灣的焦元溥博士、加拿大 的邵頌雄教授、本地的李歐梵教授,都是「繆思樂季」的好伙伴。焦博士的「音樂 與文學對話」系列(2018, 2019, 2020)固然是寓教於樂的好例子。邵教授先獨家專 訪朱曉玫,為她 2014年的演奏會作鋪墊;隨後在「人文 ‧ 巴赫」(2015)與李教授 暢談巴赫創作中的人文思想。兩位教授的對談往後還發展出一本文集《諸神的黃昏》, 由「繆思樂季」策劃,牛津大學出版社出版(2019)。

說到與眾同樂,不能不提2017年推出的「眾聲齊頌《彌賽亞》」。這個每次由不同 的本地指揮、樂手、歌唱家與觀眾普天同慶的活動,已是不少熱愛合唱的樂迷每年 臨近聖誕翹首以待的節目。

過去三年疫情肇虐,看著精心策劃的節目不得不一個接一個取消,「繆思樂季」的團隊 並沒有因此而氣餒,還隨即變陣,陸續推出推介本地年輕音樂家的「薄暮樂敘」示範 講座(2020, 2021, 2022)、與香港管弦樂團合辦的「聚焦管弦」室樂系列(2021, 2022, 2023)、梅湘四重奏首演80週年系列(2021),還有與美國巴德音樂學院、M+博物館 共同籌劃的《水墨藝術與新音樂》中西混合室內樂創作交流項目(2021, 2022)。

「繆思樂季」今年剛滿十歲,但它不會以原來配水庫的「服務超過半世紀」為限。 因為,十年樹木,百年樹人,像「繆思」這樣的一個樂季,十年,只是一個開始。

陳慶恩教授