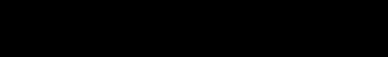

KONSTANTIN LIFSCHITZ

Konstantin Lifschitz has established a worldwide reputation for performing extraordinary feats of endurance with honesty and persuasive beauty. He is giving recitals and playing concertos in the world's leading concert halls, besides being an active recording artist. His performance was praised as "the most magical moment" and "deeply satisfying" by The Independent , and "naturally expressive and gripping" by The New York Times.

Born in Kharkov, Ukraine in 1976, at the age of five, Lifschitz was enrolled in the Gnessin Special School of Music in Moscow as a pupil of Tatiana Zelikman. After graduating he continued his studies in Russia, England, and Italy where his teachers included Alfred Brendel, Leon Fleisher, Theodor Gutmann, Hamish Milne, Charles Rosen, Karl-Ulrich Schnabel, Vladimir Tropp, Fou T'song, and Rosalyn Tureck, mostly at the Lieven International Piano Foundation.

Since his sensational debut recital in the October Hall of the House of Unions in Moscow at the age of 13, Lifschitz performs solo recitals at major festivals and the most important concert venues worldwide and appears with leading international orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, to name a few.

As a soloist, Lifschitz has collaborated with leading conductors such as Mstislav Rostropovich, Vladimir Spivakov, Yury Temirkanov, Sir Neville Marriner, Bernard Haitink, Sir Roger Norrington, Fabio Luisi, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Marek Janowski, Eliahu Inbal, Mikhail Jurowsky, Andrey Boreyko, Dimitry Liss, Dmitry Sitkovetsky, Alexander Rudin, and Christopher Hogwood.

4

As a chamber musician, Lifschitz has collaborated with such artists as Gidon Kremer, Maxim Vengerov, Vadim Repin, Misha Maisky, Mstislav Rostropovich, Natalia Gutman, Dmitry Sitkovetsky, Lynn Harrell, Patricia Kopatchinskaja, Daishin Kashimoto, Leila Josefowicz, Carolin and Jörg Widmann, Sol Gabetta, Eugene Ugorski, Alexander Knyazev, and Alexander Rudin.

Lifschitz appears as a conductor with such ensembles and orchestras as Moscow Virtuosi, Century Orchestra Osaka, Solisti di Napoli Naples, Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra Wernigerode, St. Christopher Chamber Orchestra Vilnius, Musica Viva Moscow, Lux Aeterna and Gabrieli Choir Budapest, Dalarna Sinfonietta Falun, and Chamber Orchestra Arpeggione Hohenems. Leading from the piano, he released all of Bach's seven keyboard concertos with the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra which led to another European tour. In 2019 he successfully led the China journey of the Lucerne Chamber Philharmony, which was founded and artistically directed by himself.

As a prolific recording artist, he has been releasing numerous CDs and DVDs, many of which have received exceptional reviews. Amongst them are eight recordings for the Orfeo label including Bach Musical Offering , the 'St. Anne' Prelude and Fugue, and Three Frescobaldi Toccatas (2007), Gottfried von Einem Piano Concerto with the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (2009), Brahms Second Concerto and Mozart Concerto K. 456 under Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (2010), Bach The Art of Fugue (2010), the complete Bach Concertos for keyboard and orchestra with the Stuttgart Kammerorchester (2011), Goldberg Variations (2015), and 'Saisons Russes' with works of Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, and Jakoulov (2016). In 2008, a live recording of Lifschitz's performance of Bach Well-Tempered Clavier (Books I and II) at the Miami International Piano Festival was released on DVD by VAI. In 2014, Beethoven's complete Violin Sonatas with Daishin Kashimoto were released by Warner Classics. In 2020, to celebrate the composer's 250-year jubilee, Lifschitz released CD and Vinyl boxsets of Beethoven 32 Piano Sonatas with Alpha Classics (live recordings at HKU).

Lifschitz is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music in London and has been appointed a professor of the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts since 2008.

5

Konstantin Lifschitz in Recital

15 APR 2023 | SAT | 8PM

RACHMANINOV Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Op. 42

Theme. Andante

Var I. Poco più mosso

Var. II. L'istesso tempo

Var. III. Tempo di Minuetto

Var. IV. Andante

Var. V. Allegro (ma non tanto)

Var. VI. L'istesso tempo

Var. VII. Vivace

Var. VIII. Adagio misterioso

Var. IX. Un poco più mosso

Var. X. Allegro scherzando

Var. XI. Allegro vivace

SHOSTAKOVICH 24 Preludes, Op. 34

No. 1 in C major, Moderato

No. 2 in A minor, Allegretto

No. 3 in G major, Andante

No. 4 in E minor, Moderato

No. 5 in D major, Allegro vivace

No. 6 in B minor, Allegretto

No. 7 in A major, Andante

No. 8 in F-sharp minor, Allegretto

No. 9 in E major, Presto

No. 10 in C-sharp minor, Moderato non troppo

No. 11 in B major, Allegretto

No. 12 in G-sharp minor, Allegro non troppo

- INTERMISSION -

PROKOFIEV Three Pieces, Op. 59

Promenande

Landscape

Pastoral Sonatina

MEDTNER Sonata-Ballade, Op. 27

Allegretto

Introduzione. Mesto

Finale. Allegro

Var. XII. L'istesso tempo

Var. XIII. Agitato

Intermezzo

Var. XIV. Andante (come prima)

Var. XV. L'istesso tempo

Var. XVI. Allegro vivace

Var. XVII. Meno mosso

Var. XVIII. Allegro con brio

Var. XIX. Più mosso. Agitato

Var. XX. Più mosso

Coda. Andante

No. 13 in F-sharp major, Moderato

No. 14 in E-flat minor, Adagio

No. 15 in D-flat major, Allegretto

No. 16 in B-flat minor, Andantino

No. 17 in A-flat major, Largo

No. 18 in F-minor, Allegretto

No. 19 in E-flat major, Andantino

No. 20 in C-minor, Allegretto furioso

No. 21 in B-flat major, Allegretto poco moderato

No. 22 in G-minor, Adagio

No. 23 in F-major, Moderato

No. 24 in D-minor, Allegretto

7

II

- INTERMISSION -

STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring

I. Adoration of the Earth

Introduction

Augurs of Spring: Dances of the Young Maidens

Ritual of Abduction

Spring Rounds

Ritual of the Two Rival Tribes

Procession of the Elders

The Kiss of the Earth

Dance of the Earth

II. The Sacrifice

Introduction

Mystic Circles of the Young Maidens

The Chosen One

Evocation of the Ancestors

Ritual of the Ancestors

Sacrificial Dance of the Chosen One

9

IV

10

It is impossible to imagine modern piano repertory and pedagogy without the contribution of Russian composers from the late 19th century through the first half of the 20 th century. Often remarked as the 'golden age' of Russian pianism, this period saw the international careers of such household names as Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943), Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953), and Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975). Their piano compositions have since stood out amid centuries of keyboard canon for their opulent sounds, intricate forms, pyrotechnical virtuosity, and their vast emotional landscape ranging from profound melancholy to sardonic humor. In their own time though, these now widely exalted features stemmed from variously motivated artistic experiments against the backdrop of aesthetic, technological, and political changes. Indeed, this gilded era of Russian piano music was also the age of a changing world: The Viennese modernism challenged European music's long-established aural sensibility; the rise of recording, radio, and film questioned art music's alleged pretensions to media non-specificity; and the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath besieged Russian musicians' lives and livelihoods with inescapable political circumstances. Wrestling with such a changing world, the fin-de-siecle generations of Russian pianist-composers offered their responses through the piano. The tongue-in-cheek dissonances so frequently observed in Prokofiev's music may be heard as the composer's playful, but perhaps also ambivalent, engagement with atonalism; the luxurious grandeur typical of Rachmaninov's piano writing may recall the cinematic sound of Hollywood, where the emigrant musician lived out the last years of his life; and the regularly deployed madcap moments of musical farce in Shostakovich's compositions may be

11

tucking away messages of either veiled resistance or bitter acquiescence to the cultural politics the composer endured. Yet, more than bearing earwitness of a tumultuous period in history, the piano music of Prokofiev, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, and their compatriot colleagues has also outlived their own time thanks, in no small part, to the creativity, labour, and commitment of generations of latter-day pianists, your artist(s) today included, who have taken upon themselves to tackle the technical and interpretive challenges in bringing this music alive with an unfailing sense of immediacy: an immediacy that allows our hearings of these Russian piano classics to overlap with the complex emotional world of their progenitors, and allows us to contemplate the commonalities between their times and our own.

A contemporary of Rachmaninov's, Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951) was also a Moscow Conservatory-trained pianist and composer. Despite his relative obscurity today, Medtner was among the foremost Russian composers of piano music from the first half of the 20th century. Contrasting Rachmaninov's international concert career, Medtner eschewed the limelight—a deliberate act to keep his art from commercial entrenchment. During Medtner's exile following the 1917 Revolution, Rachmaninov, with whom Medtner maintained a lifelong friendship, secured him an American tour in 1924. In America, Rachmaninov often heeded his manager's recommendations, including "never play pieces lasting longer than 17 minutes" so as not to try the patience of his American audience. While Rachmaninov's quick adaptation to American concert culture and business may indeed have brought him fame and prosperity, Medtner, often described by his colleagues as shy, aloof, and lofty-minded, was not one to succumb to commercial pressure. Instead, he insisted on presenting lengthy recitals exclusively of his own music, often including large-scale, multimovement piano sonatas. Following his commercially unsuccessful American tour, he subsequently lived in Germany and France for short periods before settling in North London in 1935. That same year, he published a tract entitled The Muse and the Fashion , in which he expounded a vehement defense of Romantic music against European music's decisive swerve towards modernism. Towards the end of his life, Medtner found patronage from the Maharajan of the Indian state of Mysore, who established the Medtner Society and launched a

12

project to have his complete piano works recorded with the composer himself as soloist. Medtner managed to record all of his works before his death in 1951.

Medtner's music champions the familiar tropes of late Romanticism: chromatic harmony, lush melody, and full-bodied texture, but amid these old familiars, one can also easily find the composer's distinctive voice, characterised by his pensive expression and folkloric imagination. Fairy tale, or 'skazka', after which Medtner named as many as 38 of his piano pieces, is a unique type of character composition that Medtner cultivated throughout his career. Some of these pieces carry subtitles, but it is uncertain whether the composer had specific programmes in mind despite the allusions. Perhaps they are more, as one Medtner scholar has claimed, "tales of personal experiences and conflicts in one's inner life" than descriptive stories. Ranging from the charming to the epic, from the urbane to the pastoral, these Fairy Tales attest to Medtner's equally eloquent and intense style, as well as his superb ability to construct captivating musical narratives. Among the selection for the present concerts: Op. 20, No. 2, 'Campanella', or bell song, produces a portentously menacing effect as befits its illustrative marking at the beginning, pesante: minaccioso, sempre al rigore di tempo e sostenuto; Op. 26, No. 3 contains some of Medtner's most ingenious harmonic sleight of hand; Op. 35, No. 4 reenacts the storm-calling scene in Shakespeare's King Lear with a tempestuous series of proliferating polyrhythmic patterns, to which Medtner added the quote "Blow, winds! Blow until your cheeks crack!"; and Op. 42, No. 1, the 'Russian Tale', draws inspiration from traditional folk music, contrasting the composer's often high-minded contemplation by returning to formal and melodic simplicity. The same kind of fantastical meandering characteristic of the Fairy Tales also permeates many of Medtner's other compositions, including his imaginative Sonata-Ballade, Op. 27 of 1912. Shorn up by an intricate web of motivic connections enlivened by an extended harmonic palette, the Sonata-Ballade traverses a vast emotional and spiritual landscape, as it transports listeners from glistening beauty, through turbulent conflicts, to joyous celebration.

Before the time of Medtner and Rachmaninov, Russian music of the 19 th century was a scene dominated by the so-called 'Mighty Five', a group of five

13

composers who banded in the 1860s to promote Russian national identity through their music by carving out a style distinct from such ready-made European models as German lieder or Italian opera. Among the group's members, Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) was a unique voice, known for incorporating Eastern modal harmonies, unconventional orchestration, and folk melodies in his composition. The piano suite, Pictures at an Exhibition , is arguably his best-known work. Written in 1874 in tribute to Mussorgsky's friend, the artist Viktor Hartmann, whose career was cut short at the age of 39. The friendship between Mussorgsky and Hartmann shared a common root in their searches for a national art, one which drew its strength from the legacy of Russian folklore. Several of the original paintings on which Mussorgsky based his Pictures have been lost, the creative spirit behind them, however, may be said to live on in audible forms through Mussorgsky's deeply felt musical depictions. The suite has inspired countless visual artists over the years, and it has also been arranged for orchestra by many composers, most notably by Maurice Ravel in 1922.

Representing a viewer walking through the exhibition, the suite is structured with five Promenades , recurring musical interludes with variations serving to reflect the composer's changing feelings about the various paintings as he encountered them. Between the Promenades are 10 movements, each representing a different painting. These movements are diverse in character, ranging from playful depictions of children's toys, through surreal imaginations of animatronic costumes, to haunting evocations of catacombs and sepulchers. Gnomus , the first painting the composer saw, was originally a sketch of a wooden nutcracker magically brought to life as a misshapen dwarf. Il vecchio castello ('the old castle') and Tuileries were architectural and landscape paintings with incidental human figures, which Mussorgsky amplifies in his music first with a gentle but gloomy song evocative of a hurdy-gurdy-accompanied dirge sung by a journeyman bard, and then with a scherzo depicting a group of quarreling children in the Parisian gardens. The slow but incessant bass ostinato in Bydło ('ox cart') captures the heavy trudge of the draft animal, and by contrast, the fleeting acciaccaturas in Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks, the following movement, aptly renders the absurd comedy of a human-sized feathery costume. ‘Samuel’

14

Goldenberg and ‘Shmuÿle’ were portraits of two Polish Jews, one rich and one poor. The original painting of Limoges, le marché ('the marketplace at Limoges’) is presumed lost, but Mussorgsky's music seems to be depicting a scene at the street market, with a group of chattering men and women in the foreground. The original painting of Catacombæ depicted Hartmann himself examining the catacombs of Paris, but through his music, Mussorgsky brings his listeners into the grief he experienced at the artist's death. The grieving continues into the second part of the movement, Cum mortuis in lingua mortua ('with the dead in a dead language'), to which the composer added a footnote in the score, "Well may it be Latin! The creative spirit of the departed Hartmann leads me to the skulls, calls me close to them and the skulls glow softly from within." The final two movements of the piece are imbued with an unmistakably Russian essence. The painting by Hartmann, The Hut on Fowl's Legs, is masterfully brought to life by Mussorgsky's music, as one hears how the hut jolts and then takes flight through a nocturnal sky, accompanied by the harrowing imagery of the folkloric witch Baba Yaga grinding human bones to power her craft. The Great Gate of Kyiv was an architectural design of Hartmann's that was never actually constructed. Nonetheless, in Mussorgsky's imagination, the gate stands in all its grandeur, as he envisions the chanting of priests and a religious procession, culminating in the triumphant return of the Promenade theme, rounding off the walk-through at the exhibition with sublime elation.

Rachmaninov's Variations on a Theme of Corelli make use of La Folia, one of European music history's most enduring tunes. The tune's origin may be traced back to the folk music of late 15th-century Portugal, where it was used to accompany dances in popular festivals, and its name, meaning 'folly' in Italian, refers to dancers' frenzied twirls. A century later, La Folia spread to nearby Spain and then across the Mediterranean to Italy via the Spanish musicians working there. Its distinctive and evocative chord progression appealed to many musicians of the Baroque era, who then improvised and composed variations on the tune as well as bent the music to fit the changing tastes of their own time, sometimes transmuting its original frolic and fancy into courtly elegance and decorum. Corelli, Handel, and Vivaldi all riffed on this famed tune, and Rachmaninov continued this tradition by furnishing La Folia's time-

15

tested harmonic formula with deeply felt Romantic fervor. The variation set is conceived as a unity, with an intermezzo (or a cadenza, rather) before the 14th variation, and final quick variations leading to a gentle coda. Distinguished by its textural clarity and harmonic audacity, the ambitiously scaled Corelli Variations—perhaps a symbol of renewed confidence after his unsuccessful Piano Concerto No. 4—represents a new phase in Rachmaninov's creative trajectory, foreshadowing the great successes of his Paganini Rhapsody and Symphony No. 3 which immediately followed.

From Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier to Chopin's 24 Preludes, composition sets organised by a complete traversal of the 24 major and minor keys are not only pedagogical staples for learning to play and to improvise on keyboard instruments, but they also become a litmus test for compositional prowess, as one is expected to display a wide variety of expressions, moods, and characters within a prescribed procedure of cycling through the keyboard's chromatic gamut. A 20 th -century essay in this august tradition of keyboard preludes, Shostakovich's 24 Preludes, Op. 34 are testaments to his immense skills and creativity as a first-rate composer for the piano and a pianist, an achievement sometimes overshadowed by Shostakovich's better-known symphonies, operas, and film scores.

Despite their brevity, Shostakovich's 24 Preludes, organised according to the circle of fifths (i.e., C major and A minor, followed by G major and E minor, and so on), are character vignettes, each with a unique and memorable design. Across the cycle, Shostakovich juxtaposes not only a wide range of affects and moods, from the humorous to the contemplative, as well as diverse compositional styles and techniques, ranging from neo-Baroque counterpoint to Jazz-inspired syncopations. These juxtapositions imbue the 24 Preludes with a playful, almost whimsical quality, which sets them apart from the portentous and trenchant strains often found in Shostakovich's other works. The opening prelude begins with a simple and modest alberti bass only to quickly meander into a series of piquant harmonies. Shifting into the relative minor, the 2nd prelude stands out for its highly gestural rhythmic clusters. The 3rd prelude is mostly gentle and melancholic, in contrast with the 4th prelude, which is ruminative and learned,

16

harkening back to the contrapuntal style of the high Baroque. The 5th prelude is etude-like, with its cavorting passagework, while the 6th's jagged melodic profile gives rise to its distinctively ludic quality. The serene 7 th prelude is especially complemented by the zany gait of the 8 th and the perpetual motion of the 9th. The 10th and the 11 th preludes make up a contrasting pair of melancholy and comedy, while the 12th's free-flowing lyricism stands opposite the 13th's economical theme and accompaniment. The elegiac 14 th prelude takes on a darker hew, but the mood is soon lightened by the effervescent 15 th and the care-free 16 th. In the 17 th prelude, one hears a reminiscence of Chopin's nocturnes, but the lively and playful 18th immediately brings the listener back to Shostakovich's world. The gentle sways in the 19 th prelude, a barcarolle , are contrasted with the energetic fury of the 20th. The bubbly 21st prelude is followed by the deeply reflective 22nd. The 23rd prelude then introduces a new sound world, veiled and ethereal, before the last prelude, pithy and humorous, rounds out the cycle.

Another set of pithy character pieces, Three Pieces, Op. 59 by Prokofiev were composed in 1934 shortly before the composer returned to the Soviet Union after his period of living abroad. Most of this foreign period was spent in France, and these three pieces perhaps could lend a glimpse into what he might have drawn from the Gallic influences. The first two pieces, Promenade and Landscape take on an arid quality that is in stark contrast with the severe and sometimes sardonic style often observed in Prokofiev's more substantial compositions. At once exquisite, playful, and somewhat ambivalent, these two short pieces are superseded by the last piece, Pastoral Sonatina, which exudes gentle charm and urbane lyricism.

Rachmaninov's Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2 marks the beginning of the composer's foray into the long-standing genre of keyboard prelude. It was written in the fall of 1892 and premiered by the composer at the Moscow Electrical Exposition staged by the Imperial Russian Technical Society. The immense popularity the Prelude enjoyed ever since brought as much fame as embarrassment for the composer, as audiences everywhere began to clamor for its inclusion in any recital programme of Rachmaninov's. Owing also to the

17

neglect of his publisher to copyright the music, haphazard arrangements by others for a motley combination of instruments kept springing up, ranging from trombone quartet, to marching band, to solo banjo.

After the Prelude in C-sharp minor, Rachmaninov adopted a more systematic approach to his preludes. Together with the Prelude in C-sharp minor, Rachmaninov's first set of 10 Preludes, Op. 23 (1903) and his second set, 13 Preludes, Op. 32 (1910) make up a total of 24 pieces encompassing all major and minor keys. Frequently alternating between tranquil lyricism and passionate drama, these preludes are hallmarks of Rachmaninov's signature style, frequently evoking the mood, expression, and technique found in his larger compositions such as the well-known Piano Concerto No. 2, which was completed in 1901. These wide-ranging preludes make for a scintillating emotional world of their own, as one hears cascading chromatic deluges, bustling polyphonic passages, and meticulously calculated climactic eruptions, contrasted with simpler melodies imbued with effortless charm, modal sonorities alluding to the Slav mystique, and labyrinthine harmonies evoking a mixture of mysticism and nostalgia.

Compositions for two pianos are rarities within the repertory of Russian concert piano music. While solo compositions are often considered the more serious vehicles for the ambitious pianists, the two-piano repertory reveal yet a more playful, light-hearted, and perhaps collegial side of the Russian piano virtuoso culture. Two Pieces, Op. 58, composed by Medtner around 1940, is a case in point. Joined by pianist Arthur Alexander, Medtner played the set for the public for the first time in a BBC radio broadcast on March 3, 1946, following his prior engagements with the radio including a broadcast of his playing Beethoven's 'Appassionata' Sonata on New Year's Day. The Two Pieces are individually titled as follows: Russian Round Dance , dedicated to Medtner's pupil Edna Iles, and Knight Errant , dedicated to the Russian-born piano duo Vronsky & Babin. The first piece of the set loosely resembles a khorovod, a type of brisk Russian dance music, and the second opens with a robust theme which is then elaborated and transformed through a series of sonata-formal procedures.

18

Rachmaninov's Suite No. 2, Op. 17 is another example of collegial collaboration at the pianos. Together with his cousin and teacher Alexander Siloti, Rachmaninov premiered the work at a concert of the Moscow Philharmonic Society on November 24, 1901. Full of lush melodies and florid passagework, the Suite, albeit conventional in style, strives to assemble an engaging variety of musical ideas and tonal colors that consistently grip the listener's attention. It also carefully attends to blending the two piano parts together to such a degree that they can hardly be distinguished. The Suite begins with a chordal and energetic March, continues with a dazzlingly hypnotic Walz, a luxurious and ecstatic Romance, and culminates with a highoctane Tarantelle which closes with a coda laden with fast-moving acrobatics at the keyboards.

Like Rachmaninov, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) also ended up settling in America as an expatriate following his decades-long exile from Russia, but it was in Paris where he first rose to international fame as the composer for Ballets Russe, a ballet company led by the resourceful impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Stravinsky wrote The Rite of Spring for the company's 1913 season, and it was premiered at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on May 29, 1913. The three chief collaborators behind The Rite of Spring were Stravinsky himself, the Slavic folklore expert and stage designer Nicholas Roerich, and the choreographer and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. In a letter to Diaghilev, Roerich explained his conception of the work, "My object was to present a number of pictures of earthly joy and celestial triumph, as understood by the Slavs." The French poet Jean Cocteau wrote of it as "a masterpiece; a symphony impregnated with savage pathos, with earth in the throes of birth, noises of farm and camp, little melodies that come from the depths of the centuries, the painting of cattle, deep convulsions, prehistoric georgics."

The music of The Rite of Spring is brutal, repetitive, and highly complex. Its savage violence confronts head-on the aesthetics of impressionism championed by Stravinsky's contemporaries Debussy and Ravel, who were at the time the paragons of Parisian musical life. Having pitilessly edited out the seamless flow of Romantic and Impressionistic music, The Rite of Spring

19

becomes a kind of cubist music, in the sense of how its sonic materials sound as if they were superimposing upon and slicing into one another with their jagged edges. At the same time of making audible the brutality and otherness of the primitive rite, Stravinsky also invokes the oriental sounding octatonicism, seeking validation for his stylistic extravagances in self-professed ethnographic authenticity. Though primarily known as a version used during dance rehearsals, the two-piano arrangement of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring has been recorded and performed as a composition in its own right. Its popularisation as a concert piece owes partly to Michael Tilson Thomas and Ralph Grierson's 1967 performance to which Stravinsky gave his own blessing. Some 50 years earlier, though, Stravinsky played the same version with Claude Debussy at a private party at the home of the French music critic Louis Laloy. As Laloy later recounted, "Debussy agreed to play the bass. Stravinsky asked if he could take his collar off. His sight was not improved by his glasses, and pointing his nose to the keyboard and sometimes humming a part that had been omitted from the arrangement, he led into a welter of sound the supple, agile hands of his friend. Debussy followed without a hitch and seemed to make light of the difficulty. When they had finished there was no question of embracing, nor even of compliments. We were dumbfounded, overwhelmed by this hurricane which had come from the depths of the ages and which had taken life by the roots."

Programme notes by Morton Wan MPhil in Musicology, HKU PhD Candidate in Historical Musicology, Cornell University

20

HKU MUSE 10 Years

In the last 10 years, MUSE has amused, bemuse and confused the standard practices in concert presentations, bringing new ideas and energies to the cultural offering in Hong Kong. In doing so, it has raised the University as a major force in cultural leadership, and as a cultural hub for the HKU community and friends. Most of all, MUSE has been a muse for many: inspiring us to explore, create, and think more deeply. MUSE has made the Grand Hall, with its astounding acoustics, a cultural home, a cultural lab, and a living room that lives and breathes live music anew. There are

‧ MANY DEBUTS, such as Berliner Barock Solisten, Khatia Buniatishvili, Jeremy Denk, LENK Quartet, Yunchan Lim, Jan Lisiecki, NOĒMA, Nobuyuki Tsujii, Zhu Xiao-mei;

· MANY FIRSTS, such as the release of Beethoven 32 Sonatas Vinyl and CD boxsets with Alpha Classics, the publishing of In Time with the Late Style book with Oxford University Press, and the launch of Around Twilight LectureDemonstration and the Music in Words podcasts;

· MANY RETURNING STARS, such as Angela Hewitt, Paul Lewis, Konstantin Lifschitz, Jean Rondeau, and Takács Quartet;

· MANY NEW WORKS by HKU composers, such as David Chan, Owen Ho, Anthony Leung, Peter Tang, Kiko Shao, and Jing Wang;

· MANY STUDENT ENGAGEMENTS, such as writing programme notes, performing alongside professional musicians, and gaining practical art administration experience;

· MANY IN-DEPTH EXPLORATIONS on monumental works, such as the complete cycle of Beethoven Violin Sonatas, Bartók String Quartets, Bach Well-Tempered Clavier, Schubert Piano Sonatas, and Schubert Song Cycles;

And, most importantly, there are many collaborations and amazing moments that will always be treasured by our audiences. What's your unforgettable MUSE moment? That's why we are here—to make the invaluable possible. So as we celebrate our 10 th anniversary, be a muse for us in whatever way you can to encourage MUSE for years to come.

Prof. Daniel Chua

於2013年啟用的李兆基會議中心大會堂是港大百週年校園的亮點建築,原址為 水務署的配水庫,服務港島各區超過半世紀。「繆思樂季」與大會堂同步誕生, 致力令這個具備美妙音響效果的場地成為普羅大眾樂意踏足,並不時流連忘返的 「知識庫」。

「繆思樂季」起步之初即另闢蹊徑,朱曉玫的《哥德堡變奏曲》(2014)、呂培原的琵 琶古琴演奏會(2014),至今仍為樂迷津津樂道。往後列夫席茲的貝多芬鋼琴奏鳴曲 全集(2017)、休伊特的巴赫平均律鍵盤曲集(2018)、以及近年塔克斯四重奏的巴爾 托克全集(2019),均開風氣之先,提供現場聽全某一整卷音樂經典的機會,一新觀 眾耳目。其中,列夫席茲八場音樂會的現場錄音,「繆思樂季」還與Alpha Classics 合作,發行了全球限量版的黑膠和鐳射唱片(2020)。

推廣知識交流是大學的使命,「繆思樂季」除了在節目策劃上與音樂系合作無間,還 不時邀請系內老師與樂手或嘉賓以對談、導賞、示範講座等形式,將相關的人文知 識一點一滴、深入淺出介紹給觀眾,冀能做到寓教於樂,與眾同樂。

但「繆思樂季」的合作對象並不囿於港大校園。樂評人如臺灣的焦元溥博士、加拿大 的邵頌雄教授、本地的李歐梵教授,都是「繆思樂季」的好伙伴。焦博士的「音樂 與文學對話」系列(2018, 2019, 2020)固然是寓教於樂的好例子。邵教授先獨家專 訪朱曉玫,為她 2014年的演奏會作鋪墊;隨後在「人文 ‧ 巴赫」(2015)與李教授 暢談巴赫創作中的人文思想。兩位教授的對談往後還發展出一本文集《諸神的黃昏》, 由「繆思樂季」策劃,牛津大學出版社出版(2019)。

說到與眾同樂,不能不提2017年推出的「眾聲齊頌《彌賽亞》」。這個每次由不同 的本地指揮、樂手、歌唱家與觀眾普天同慶的活動,已是不少熱愛合唱的樂迷每年 臨近聖誕翹首以待的節目。

過去三年疫情肇虐,看著精心策劃的節目不得不一個接一個取消,「繆思樂季」的團隊 並沒有因此而氣餒,還隨即變陣,陸續推出推介本地年輕音樂家的「薄暮樂敘」示範 講座(2020, 2021, 2022)、與香港管弦樂團合辦的「聚焦管弦」室樂系列(2021, 2022, 2023)、梅湘四重奏首演80週年系列(2021),還有與美國巴德音樂學院、M+博物館 共同籌劃的《水墨藝術與新音樂》中西混合室內樂創作交流項目(2021, 2022)。

「繆思樂季」今年剛滿十歲,但它不會以原來配水庫的「服務超過半世紀」為限。 因為,十年樹木,百年樹人,像「繆思」這樣的一個樂季,十年,只是一個開始。

陳慶恩教授

十年樂事:像「繆思」這樣的一個樂季

24

... one of the most gratifying interpretations of the

South China Morning Post

R E C O R D E D A T T H E U N I V E R S I T Y O F H O N G K O N G B E E T H O V E N 3 2 S O N A T A S K O N S T A N T I N L I F S C H I T Z 1 7 - L P W O R L D W I D E L I M I T E D E D I T I O N B O X S E T 1 0 - C D B O X S E T

piano sonata cycle.

Magazine R E L E A S E D O N A L P H A C L A S S I C S

vinyl or CD, Beethoven sonatas

in Hong Kong shine.

Beethoven

Gramophone

On

recorded