23 minute read

Pyramid Scheme: Collecting Coins of the Ptolemaic Empire by Dave Michaels

By David S. Michaels

The Pyramids at Giza were already more than 2,200 years old when the Macedonian king Alexander III, later called the Great, arrived at Memphis in 332 BC. The Egyptian priestly caste promptly switched allegiance from the Persians, the previous occupiers, to their new Macedonian masters, proclaiming them as liberators and Alexander as true heir to the pharaohs of ages past.

Alexander proceeded to the sacred site of Siwa in the Libyan desert, where an oracle pronounced him the son of the great god Amun, whom the Greeks likened to Zeus. He took the oracle seriously, as it fit with his notion that he was god-sired, if not divine. As he prepared to move on, Alexander decided to place his mark on Egypt by founding a city at the mouth of the Nile Delta. Allegedly, he traced out the city plan himself. This Alexandreia would soon become one of the world’s great cities, capital to a new era of Egyptian greatness.

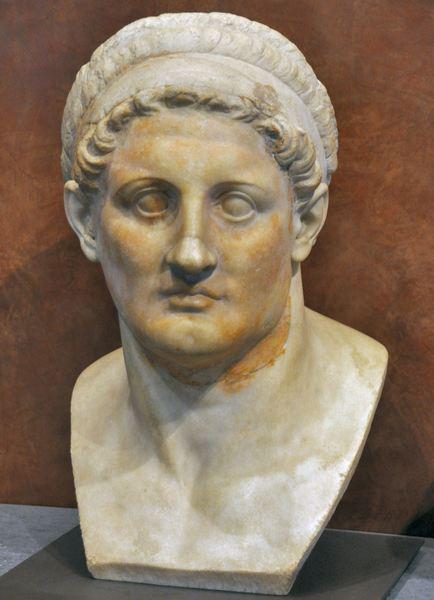

Accompanying Alexander in this visit was his close friend Ptolemy, an officer in the elite Companion Cavalry. As canny as he was capable, Ptolemy took careful note of Egypt’s enormous assets, including its easy defensibility, the agricultural bounty provided by the Nile’s periodic flooding, and the rich gold mines of Nubia and the eastern deserts. Upon Alexander’s death in 323 BC, Ptolemy sought and was granted the prized satrapy of Egypt. Alone among the Diadochi (“successors”), he was content with this sphere of influence and resisted all temptation to grasp for supremacy over the whole of Alexander’s vast empire. In 306 BC, he assumed the royal title of Basileos (king), making himself heir to three millennia of Egyptian Pharaohs. His male and female descendants would rule Egypt and its provinces for nearly three centuries, until the fall of Kleopatra VII in 30 BC.

Figure 1: Ptolemy I Soter, bust in the Louvre.

Rich Legacy

The Ptolemaic Empire lasted longer than any other major Hellenistic kingdom and left a rich legacy for future scholars and collectors in the form of an extensive coinage in gold, silver, and bronze. These beautiful coins have been collected and studied for centuries, most notably by Ionnis Svoronos (1863-1922), a Greek archaeologist and numismatist whose 1904 publication Ta Nomismata tou Kratous ton Ptolemaion remains the most extensive scholarly study of the entire series. In recent years his torch has been picked up by Catharine Lorber, whose “Coins of the Ptolemaic Empire” (ANS, 2018) employs the latest scholarship to survey the first four reigns of the dynasty, from Ptolemy I Soter through Ptolemy IV, from 323 BC to 204 BC, often termed the Empire’s Golden Age.

This period set the pattern for the entire Ptolemaic pageant in terms of coin design, denominations, and mint designation. These rulers struck truly stunning coins in gold, silver, and bronze, remarkably for their sheer size and weight as well as their highly artistic designs.

Collectors of the Ptolemaic series face a few challenges. Gold coins, as might be expected, are usually quite pricey. In contrast, the basic unit of the Ptolemaic economy, the silver tetradrachm, is widely available, usually at comparatively modest price. However, unlike other Hellenistic kingdoms that feature a portrait gallery of rulers, the vast majority of Ptolemaic silver coinage depicts the dynasty’s founder, Ptolemy I Soter (“savior”), with only a relative few special issues portraying the contemporary ruler. Yet this is a highly sophisticated coinage, whose evolving style and vast assortment of mintmarks, symbols, and regnal dates will reward careful scrutiny.

Here is a brief rundown of the most important and intriguing Ptolemaic kings and queens, and the coins they created:

Ptolemy I as Satrap

As Satrap (323-306 BC), Ptolemy’s earliest coinage was modeled on that of Alexander the Great: gold staters of the Athena / Nike type and silver tetradrachms with the familiar portrait of Herakles wearing a lion skin, along with Alexander’s name and royal title. These early silver tetradrachms were on the same Attic standard employed by most mints outside of Macedon proper, with a tetradrachm of approximately17.25 grams. Starting in Memphis, the mint was soon relocated to Alexandreia, with subsidiary mints in the outlying provinces of Cyprus, Kyrenaica, and Phoenicia. Control marks included a ram’s head, symbolic of the god Amun, and a rose. While not particularly rare in today’s market, these Egypt-mint Alexander tetradrachms tend to be struck from beautifully engraved dies and hence fetch a premium price, usually in the low to mid five-figures.

Figure 2: Tetradrachm in name of Alexander III, Memphis, c. 323-211 BC (CPE 19), current CNR 525581. Figure 3: Tetradrachm of Ptolemy I as Satrap, c. 319 BC, CPE 33 (ex Triton XXII, lot 400).

About 319 BC, Ptolemy began altering the design of the silver: Alexander’s portrait replaced Herakles, this time wearing an elaborate elephant-skin headdress recalling his victories in India. A few years later, the reverse also changed to a striding figure of Athena Promachos, with a subsidiary design of an eagle perched on a thunderbolt, probably Ptolemy’s personal blazon. In 313/2 BC, the weight was reduced, the first of several reductions that eventually ended up with a tetradrachm of about 14.25 grams. This approximated the lighter Phoenician standard and the one employed in Macedon proper at the time. Moreover, it enabled Ptolemy to set up a closed economic system that would benefit the Egyptian treasury for centuries to come, as anyone entering the kingdom from one of the other Hellenistic states was forced to change their heavier coins for the lighter Ptolemaic issues, with the treasury skimming off the difference.

The Satrapal tetradrachms of Ptolemy usually start at around $1,000 in VF condition, with the earlier full-weight examples commanding much more. An unusual feature of these coins is the common presence of graffiti, usually in the form of Greek letters scratched on the reverse fields; evidently it was common practice to “make your mark” on coins in Ptolemaic times.

Figure 4: Ptolemy I, reduced standard, c. 306-300 BC, CPE 72 (Triton XXIV, lot 799).

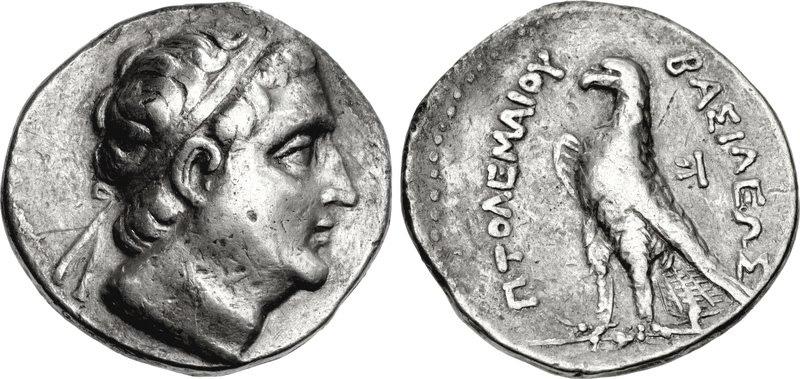

Ptolemy I as King

Upon assuming the royal title in 306 BC, Ptolemy began placing his own portrait and name on gold staters, with a reverse showing the deified Alexander in a chariot pulled by elephants. In 294 BC, Ptolemy took the important step of placing his portrait on silver tetradrachms. The king is depicted with startling realism, with a long face, heavy, overhanging brow, deep-set eyes and a pronounced chin, a rather homely effigy starkly different from the idealized male beauty of Alexander. Both this obverse portrait and the new reverse design, an enlarged version of the eagle-on-thunderbolt blazon, would reverberate down through history, becoming the standard Ptolemaic coin types for the next two and a half centuries and influencing coin design for the next 2,000 years.

Figure 5: Tetradrachm of Ptolemy I as King, CPE 137 (Triton XXIV, lot 800) Figure 6: Ptolemy I trichryson or pentadrachm, CPE 128 (ex Triton XXII, lot 404)

Also struck was a silver coin of two tetradrachms weight, a silver octodrachm, although they were never minted in large numbers and remain very rare (hence pricey) today. More widely struck was a new gold coin of 17.85 grams, heavier than any previous gold piece; called a trychryson (“thrice golden”), today it is usually called a gold pentadrachm, At the other end of the monetary spectrum, Ptolemy introduced a range of bronze denominations to supplement the other metals. His immediate successors expanded on this, issuing huge bronze coins intended to replace the silver drachm and smaller fractions. These became the coins of everyday commerce in Egypt and helped to foster a thriving economy.

Delta Mystery

A system of control letters and symbols was introduced to keep track of issues, maintain quality control and designate branch mints. Many of the portrait tetradrachms and gold pieces have a curious feature – a tiny delta (Δ) tucked in a curl of hair behind Ptolemy’s ear. In a 1967 article in ANS Museum Notes, numismatist Orestes Zervos proposed that the delta was the furtive signature of a singularly talented die engraver who served the Alexandreia mint. While attractive, this theory could not

stand close scrutiny. The delta also appears on the earlier Alexander-elephant skin types and continues well into the next reign, meaning the “delta engraver” would have had an unrealistically long lifespan. In some tetradrachms the delta is replaced by an alpha (A) or an omega (Ω); rather than a signature, Lorber proposes that it is a “cryptic control mark” serving some as-yet unknown internal mint function.

Ptolemy I Soter died peacefully in his bed in 282 BC. His coinage types froze in place, with his portrait continuing to appear on the vast majority of silver coins issued by Ptolemaic kings and queens for the next two and a half centuries. This, plus the fact that all male rulers were named Ptolemy, often makes it difficult to determine which king struck a particular coin. In this, the Ptolemaic practice of dating coins by the king’s regnal year is helpful to modern collectors and scholars. Today, portrait silver tetradrachms attributed to Ptolemy I Soter usually fetch a premium over those attributed to his successors, though style, strike, and nice silver surfaces free of marks or graffiti are equally important in determining price.

Ptolemy II: Able Successor

As successor, his last-born and favorite son, Ptolemy II, proved to be an able ruler who built on the founder’s sound diplomacy and fiscal policies. While his wars bore mixed results, his domestic projects were many and lasting, including construction of the famous Pharos lighthouse and the world’s first Museon (“hour of the muses”), incorporating the Library of Alexandreia. Most of Ptolemy II’s silver coinage retained the types and portrait of his father, with a few exceptions. A series of rare tetradrachms struck at mints in Cilicia bear his portrait (CPE 400-406). Even more innovative are the coins that sprang from his complex marriage history. His first wife, Arsinoe I, bore him three children, including the future Ptolemy III; however, in 275 BC another Arsinoe, Ptolemy II’s full sister, arrived at court and the two women clashed, leading to Arsinoe I’s exile. In 273 BC, Ptolemy II married his sister in the manner of the old Egyptian Pharaohs. This shocked the Greek world but set a precedent for future sibling marriages within the Ptolemaic dynasty. Greek wags gave Arsinoe II the nickname Philadelphos, (“brother loving”); the new queen embraced the term. As beautiful and intelligent as she was crafty and ambitious, Arsinoe II Philadelphos became a role model for future Ptolemaic queens.

Figure 7: Ptolemy II portrait tetradrachm, Cilician mint, CPE 404 (ex CNG 93, lot 609).

Figure 8: Gold Half-Mnaieion of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II, (Triton XXIV, lot 801) Sibling Gods

The sibling marriage was marked by a new and remarkable issue of immense gold coins, each weighing nearly an ounce, bearing four portraits: those of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II on the obverse, and Ptolemy I and Berenike I on the reverse. Bearing the legend ΑΔΕΛΦΩΝ / ΘΕΩΝ (“to the sibling gods”), they mark the official deification of the ruling couple. Each coin was tariffed at 100 silver drachms, called a mina, and was hence called a mnaieion; today, this coin type is often called a gold octodrachm. A half-mnaieon (or gold tetradrachm) worth 50 drachms was also struck in considerable numbers. In a world where a silver drachm was a day’s wage for a skilled craftsman or a soldier in peacetime, each coin was worth a not-so-small fortune. The world had never seen such an ostentatious display of wealth.

After Arsinoe II’s death, Ptolemy II struck a new series of silver and gold coins with her veiled portrait alone, wearing a type of tiara called a stephane, a ram’s horn (just visible poking out from the veil), and bearing a lotus-tipped scepter over her shoulder, all symbols of divinity. Denominations include large silver dekadrachms, tetradrachms, and gold mnaieia, all carrying the symbol of a double cornucopia on the reverse along with the legend “of Arsinoe Philadelphos.” These would continue to be struck into future reigns, the gold in particular. Never before had a female ruler been so extensively honored, setting forth a continuing tradition of a strong female presence in future Ptolemaic regimes. Figure 9: Silver Dekadrachm of Arsinoe II (Triton XXIV, lot 803).

Ptolemaic III: Peak of Empire

Ptolemy II died in 246 BC and was succeeded by his son, Ptolemy III, later called Euergetes (“benefactor”). Another dynamic and capable king, his reign witnessed the peak of Ptolemaic power. Almost immediately after inheriting the throne, he launched

a major war against the neighboring Seleukid Kingdom which saw his armies advance all the way to Babylon. At one point he was tempted to seek Alexander’s mantle and unite the whole Hellenistic world under his control, but an uprising by native Egyptians (the first of many) forced his withdrawal to regain control. Ptolemy III’s image as a mighty conqueror is reflected on his coinage, which was immense and varied. While most of his silver tetradrachms portray Ptolemy I, a few of the newly won provincial mints struck coins with his own portrait. These portrait issues are all rare and fetch mid-five figure prices.

Figure 10: Ptolemy III, portrait tetradrachm, Ainos mint, cf. CPE 474A (see current CNR, 565950). His wife and co-ruler, Berenike II, also appears on a range of gold and silver denominations, including the largest of all Ptolemaic silver coins, an immense silver 15-drachm piece (pentakaidekadrachm). Svoronos knew of only two such coins; today they remain quite rare, though obtainnable in the mid six figures.

Even Ptolemy III’s bronze coins tended toward the gigantic, with the introduction of a bronze octobol, tariffed at 1.3 silver drachms, averaging 47 millimeters in diameter and weighing 92 grams. These immense bronzes are increasingly popular with collectors and prices, while still affordable, are climbing.

Ptolemy III was reputedly as avaricious for knowledge as he was for military glory, for he scoured the world for books for his library, even resorting to the trick of seizing and copying every book unloaded at the docks in Alexandreia, then returning the copies to the owners and keeping the originals. He died at the age of 58 in 222 BC, apparently of natural causes, bequeathing the throne to his eldest son, Ptolemy IV Philopator (“father-loving”). Figure 11: Berenike II, AR Pentadrachm, CPE 742 (ex Triton XXII, lot 417).

Ptolemy IV - V: Decadence and Decline

Here the Ptolemaic Kingdom’s history takes a sharp turn, for Ptolemy IV Philopator (222-204 BC) proved unworthy of his inheritance and squandered much of the power, wealth and prestige accumulated by his predecessors. Ptolemy IV’s portrait issues in silver and gold are exceedingly rare, but they depict him with a rather fleshy face and a head of curly hair. Alas, nearly all the succeeding Ptolemies were cast in his mold – fat, lazy, pleasure-loving dilettantes with little care for the people they governed.

His sister and wife, Arsinoe III, was made of sterner stuff. During the battle of Raphia against the Seleukids in 217 BC, she led her own contingent of soldiers and exhorted them on the battlefield, promising to pay them two mnaieia apiece if they rallied to victory, which they promptly did. Her own portrait appears on a very rare series of gold coins. Figure 12: Portrait Tetradrachm of Ptolemy IV (see current CNR, 531644).

Philopator’s sudden death in 204 BC left the throne in the hands of his six-year-old son, Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose reign was almost entirely controlled by various viziers. Alone among the later Ptolemies, coins actually displaying his youthful portrait are not terribly rare and readily obtainable. Once he started ruling on his own and showing signs of independence, his ministers arranged his murder and the throne once again devolved to a child, the six-year-old Ptolemy VI.

Figure 13: Portrait Tetradrachm of Ptolemy V (ex CNG 114, lot 442).

Ptolemy VI - VIII: Revival & Dynastic Turmoil

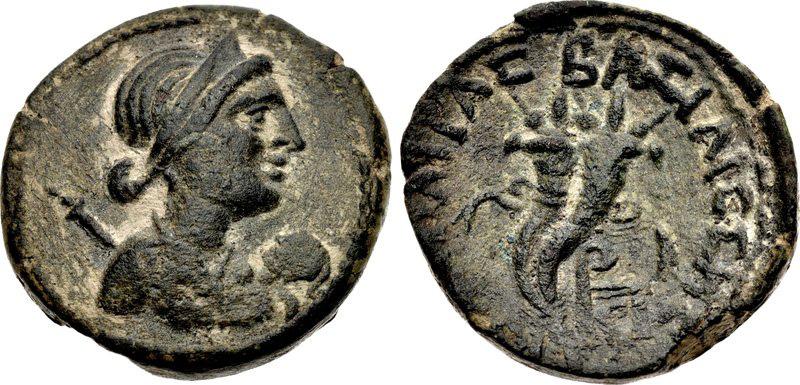

Surprisingly, Ptolemy VI Philometor (180-145 BC) survived his perilous childhood and grew into a capable ruler, the last Ptolemy to show any true governing or military skills. Unfortunately, no contemporary Egyptian coins display his portrait, although bronze coins struck in the regions he conquered, including Phoenicia, apparently depict his handsome profile, recognizable by way of a number of engraved gems of him. His silver tetradrachms of the Ptolemy Soter type are quite common and many are of exceptional style, the last reign of which this can be said. They are also usually quite affordable, unless in superb condition.

Ptolemy VI’s sister and wife, Kleopatra II, was a formidable character in her own right, whose reign continued after her husband’s tragic death in battle in 145 BC. Her female descendants, all Kleopatras, followed her example and were heavily involved in the dynastic politics of not only the Ptolemaic Kingdom, but the neighboring Seleukid Kingdom as well. Contemporary bronze coins often depict an attractive female head likely representing Kleopatra II as Isis; indeed one type has an obverse legend naming “Queen Kleopatra.” It has also been proposed that the later gold mnaieions in the name of Arsinoe II, struck in the Ptolemy VI-VIII, actually portray Kleopatra II and / or her daughter, Kleopatra III. While this theory is not universally accepted, these later queenly portraits do not much resemble the early effigy of Arsinoe II, and the ubiquitous letter K behind the head could stand for Kleopatra. Figure 14: Bronze 29mm depicting Kleopatra II as Isis.

Pot Belly and Flute Player

Alas, she also had to contend with her brother and co-ruler, the scheming, self-interested Ptolemy VIII Physcon (“pot-belly”). His extreme decadence became legendary throughout the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, though he did possess one true talent – for survival. A handful of portrait coins do exist, revealing that his nickname was certainly apt.

Figure 15: Portrait Tetradrachm of Ptolemy VIII (ex Triton XXII, lot 428). During the reigns of Ptolemy IX through XII, the fabled wealth of Egypt was frittered away on futile dynastic civil wars and massive bribes to the rising power of Rome. Unfortunately, none of these kings seems to have struck a true portrait coinage, and the ubiquitous types depicting Ptolemy I Soter show a significant decline in artistic quality, production values and silver content. The practice of dating coins by regnal year was expanded to include co-ruling kings and queens, so many coins display multiple regnal dates in Greek letter numerals (usually preceded by a symbol resembling a Latin L, meaning “year”). The mint of Paphos on Cyprus became increasingly important, producing nearly as many late Ptolemaic coins as Alexandreia. These later Ptolemaic tetradrachms are plentiful in today’s market and are generally quite affordable, although some dates in the series are quite rare.

Ptolemy XII Auletes (“the flautist,” reigned 80-51 BC) gained his nickname by his delight in playing the flute at religious festivals and artistic competitions. Like Nero, he was a better musician and performer than he was a ruler. He still managed to hold the throne for the better part of three decades, despite being usurped at one point by his eldest daughter, Berenike IV, and spending nearly three years as an exile in Rome, 58-55 BC. He had with him his favorite daughter, Kleopatra VII, who thereby gained some valuable insights into Roman psychology and set the stage for the dramatic final chapter in the Ptolemaic saga.

Kleopatra VII and Rome

Kleopatra VII’s reign, commencing in 51 BC, went through a typically Ptolemaic series of betrayals by her siblings before, in 48 BC, she found a champion in the great Roman Dictator Julius Caesar. Captivated by her charm and intelligence, he restored her throne and even married her, under Egyptian law anyway. She bore him a son in 47 BC, who went on to become Ptolemy V Caesarion, last of his line. After Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, Kleopatra made a new liaison with the Triumvir Mark Antony, who sired three more children with her. In 36 BC, Antony made Kleopatra his co-ruler over the entire eastern Mediterranean, restoring Ptolemaic Egypt to its glories under the first Ptolemy.

Of course Rome, not Egypt, held the true power here, as became evident when the strained relations between Antony and Caesar’s heir, Octavian, erupted into open civil war in 32 BC. Antony and Cleopatra soon found themselves outmaneuvered, defeated and bottled up in Alexandreia, where they both committed suicide in August of 30 BC. Ptolemy Caesarion was executed by Octavian (although he spared the children of Kleopatra and Antony), and Egypt passed under Roman control, where it would remain for another seven centuries.

Throughout the kingdom’s final decades, the Ptolemaic coinage system continued its gradual descent. Early in Kleopatra’s reign, a shortage of silver forced her to issue bronze coins artificially valued at 80 and 40 drachms for circulation within Egypt. Although these 8 Figure 16: Bronze 27mm of Kleopatra VII and Caesarion (ex CNG 105, lot 456).

Figure 17: Bronze 80 drachm of Kleopatra VII, c. 49 BC. bronze portraits of Kleopatra are frequently worn and battered, they still fetch strong prices. The domestic silver shortage was partly due to the need to pay huge armies of Roman soldiers. In 36 BC, silver tetradrachms were struck at a mint under Ptolemaic control in Syria, possibly Antioch, to pay Antony’s soldiers. These impressive coins bear portraits of Kleopatra and Antony on opposite sides; notably, her head is on the obverse. Though not exceedingly rare, these tetradrachms were struck in somewhat debased metal that was subject to corrosion over the centuries, so finding one with strong portraits and good surfaces is quite difficult today. That, combined with the marquee names of Kleopatra and Antony, make decent examples quite expensive.

Even under Roman rule, an echo of the Ptolemies lasted for centuries more in Egypt. The Romans absorbed and maintained the Ptolemaic administrative and economic system, including fundamentally the same form of coinage. The scheme set up by Ptolemy I Soter survived, if not nearly so long as the pyramids, longer than any other Hellenistic institution, and his coins carried his vision to the present day.

Figure 18: Tetradrachm of Kleopatra VII and Mark Antony, circa 36 BC, Syrian or Phoenician mint

TABLE OF PTOLEMAIC RULERS WHO ISSUED COINAGE Rarity scale (applies to coins in VF to EF condition): Common – Regularly appears in internet, print and public auctions. Gold coins usually available under $5-8,000, silver coins available under $500, bronzes $100 - $200. Scarce – Occasionally appears at auction. Gold coins available @ $10,000, silver coins @$1,000, bronzes under $300. Rare – Seldom appears at auction. Gold coins typically over $10,000, silver coins over $1,500, bronzes over $500. Very rare, Extremely rare – Each step approximately doubles value. After Ptolemy I, his portrait continues to appear on the standard silver coinage of each succeeding ruler. Where a portrait coin exists of the contemporary ruler, this is depicted and noted to the right. From Ptolemy IX through XV, no portraits exist of contemporary king, so a Ptolemy I portrait type is portrayed. Bronzes, with a few exceptions, are non-portrait.

Portrait Ruler

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy II

Reign

Satrap 323–306 BC King 306–285 BC

Rarity

Gold portrait: Scarce Silver non-portrait: Common Silver portrait: Common Bronze: Common

co-ruler from 286 BC, sole ruler 285–246 BC Gold: Common Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (his portrait): Very Rare Bronze: Common

Arsinoe II Philadelphos 273–268 BC

Ptolemy III Euergetes 246–222 BC

Berenike II 244-221 BC

Ptolemy IV Philopator 222–204 BC

Arsinoe III Thea Philopator 220-204 BC

Ptolemy V Epiphanes

Cleopatra I Syra

Ptolemy VI Philometor 204-180 BC

194-176 BC

180–145 BC

Kleopatra II 175-c. 116 BC Gold: Common Silver Dekadrachm: Scarce Silver Tetradrachm: Very Rare

Gold: Scarce Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (his portrait): Very rare Bronze: Common

Gold: Rare Silver: Very rare

Gold portrait: Ext. rare Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (his portrait): Ext. rare Bronze: Common

Gold: Ext. rare

Gold portrait: Ext. rare Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (his portrait): Scarce Bronze: Common

No coins

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Bronze: Common Bronze (his portrait?): Scarce

Gold (disguised portrait as Arsinoe II?): Common Bronze (her portrait, as Isis): Scarce

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (Physcon) 170-116 BC

Kleopatra III 141–101 BC

Ptolemy IX Soter II (Lathyros)

Kleopatra IV Kleopatra V Selene

Ptolemy X Alexander 116-107 BC; 88-81 BC

116-115 BC 115–107 BC

107-88 BC

Kleopatra Berenike III Ptolemy XI Alexander 105–80 BC 80 BC (18 days)

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (Auletes) 80-58 BC; 55-51 BC

Kleopatra VI Tryphaena Berenike IV 80-57 BC 58-55 BC

Kleopatra VII Philopator Thea Notera 51-30 BC

Ptolemy XIII 50-47 BC Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (his portrait): Ext. rare Bronze: Common

Gold (disguised portrait as Arsinoe II?): Scarce

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common

No coins No coins

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common

No coins No coins

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common

No coins No coins

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Common Silver (her portrait): Scarce Bronze (her portrait): Common

Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Scarce

Ptolemy XIV 47-44 BC Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Scarce

Ptolemy XV Caesarion 44-30 BC Silver (Ptolemy I portrait): Scarce Bronze: Rare

IMPORTANT BOOKS: GENERAL “Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age” by Peter Green (University of California Press; reprint edition 1993). A monumental and yet highly readable account of the Hellenistic World.

IMPORTANT REFERENCES AND RESOURCES: NUMISMATIC

“Coins of the Ptolemaic Empire, Part 1, Volumes 1 and 2 (Precious Metal and Bronze)” by Catharine Lorber (ANS, 2018). A massive, long-anticipated catalogue of coins struck by the first four Ptolemaic kings, it essentially rewrites the sections on these rulers in J. N. Svoronos’ classic, but now much out of date, Ta Nomismata tou Kratous ton Ptolemaion (1904). The coinage of Ptolemies I through IV is supplemented by a few issues possibly attributable to Cleomenes of Naucratis, the predecessor of Ptolemy I in Egypt, as well as by coinages of Ptolemy Ceraunus, Magas, and Ptolemy of Telmessus, members of the Lagid dynasty ruling their own kingdoms outside of Egypt. Available through the American Numismatic Society website, with direct link here: http://numismatics.org/store/lorber/

“Ta Nomismata tou Kratous ton Ptolemaion” by Ionnis Svoronos (Athens, 1904), has long been the preferred reference for Ptolemaic coinage. Though more than a century old, it still offers remarkably comprehensive coverage. It is a rare title and commands a daunting price whenever it comes up for auction; the original, moreover, is in an archaic form of Greek. However, in a tremendous service to the pursuit of numismatics, Catharine Lorber’s excellent translation and partial update of Svoronos’s work, complete with plates, is available online at Ed Waddell’s website, coin.com. A direct link is here: https:// www.coin.com/images/dr/svoronos_book2.html

Ptolemaic Coins Online (American Numismatic Society): This is a website in progress that will eventually digitize Coins of the Ptolemaic Empire as well as Svoronos’s work: http://numismatics.org/pco/?fbclid=IwAR2sAa31ax3P3vsU_ NYTjk5qbxa8S4UcwL9eEAnCTIhj-HyCRsXmylftilU