24 minute read

EMPIRES OF MYSTERY: Collecting Greco-Baktrian Coins by David S. Michaels

EMPIRES OF MYSTERY:

Collecting Greco-Baktrian Coins

By David S. Michaels

With the United States having recently concluded a costly 17-year-long war in Afghanistan, it’s become almost a truism—a “factoid” if you will—that Afghanistan is unconquerable, that it defeated Alexander the Great and every other foreign power that’s ever dared to invade it.

The problem with this notion: At least in Alexander’s case, it’s simply wrong. Alexander the Great wasn’t defeated in Afghanistan. In the fourth century BC, he invaded and conquered ancient Baktria—largely contiguous to modern Afghanistan—and it remained under the rule of Greek kings for the next two centuries. Yes, it was a tough and bitter slog that cost tens of thousands of lives. But define “success” however you will, 200 years of unbroken rule in a distant land has to count for something. These Greek kings even expanded their realm beyond the Hindu Kush and into northern India, almost unimaginably remote from their homeland.

What’s more, the Greek rulers of Baktria and northern India created something unique in history—a vibrant, diverse, multinational society that fused the cultures of Europe, Iran, Central Asia and India.

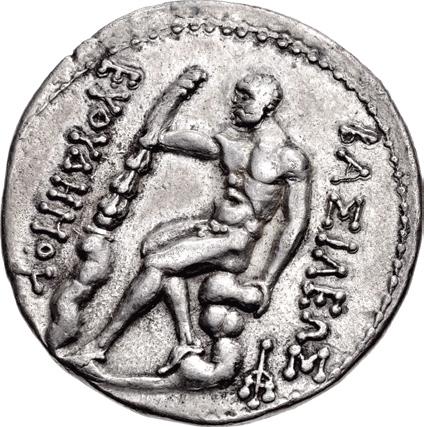

Figure 1: Silver Tetradrachmn of Eukratides I “The Great” (Triton XXV, lot 561)

From Alexander’s arrival in Baktria in 330 BC down nearly to the birth of Christ, this remarkable and exotic cultural melting pot took root and thrived, until it was finally snuffed out by new invasions of outside peoples. Today, only the faintest echoes survive. The history of these distant lands has been almost entirely erased. In all the records of ancient historians writing within a few centuries of their existence, only about 600 words refer to the Greek kingdoms of Baktria and India. Their cities have been swallowed by sand and scrub.

Only one thing has survived in any quantity—the coin of the realm. And what coins they left us: Gigantic gold medallions, silver multiples the size of tea plates, large silver tetradrachms with portraits nearly photographic in their realism, bronzes in all sorts of odd shapes and sizes. All testify to the great wealth of the land and the brilliance of the civilization that produced them.

But coins can only tell us so much. Of nearly all these rulers, we know only their names and faces, and those so faithfully rendered that if one of them walked into the room, you’d recognize him. Beyond that, it’s all guesswork. Trying to reconstruct the history of these Empires of Mystery is like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle with 90% of the pieces missing.

Where On Earth?

This saga takes place within a region the Greeks of the Classical age thought impossibly remote, barbarous, and entirely unsuitable to civilized life as they conceived it. It comprised several provinces, or Satrapies, of the old Persian Empire abutting the towering Hindu Kush Mountains, including Arachosia, Margiana, Sogdiana and Baktria; on the other side of the Hindu Kush, the Indo-Greek Kingdoms at various times included Gandhara, the Punjab, Shurasena, and Malla. These regions are now part of the “stan lands,” Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, as well as northern India. Though considered rugged and inhospitable, the realm included vast tracts of fertile fields, rich wildlife, navigable rivers, and immense mineral wealth, not to mention a sizeable native population in hundreds of small towns.

The exact boundaries of the Empires of Mystery are hard to establish, and shifted this way and that over three centuries of Greek occupation. Though usually spoken of as a singular “Greco-Baktrian Empire” or “Indo-Greek Kingdom,” it is clear the political entities were rarely, if ever, unified, which is why this article refers to them in the plural.

Alexander in the Orient

Alexander III “the Great” was only 20 when, in 336 BC, he inherited the Kingdom of Macedon from his father, Philip II. He bequeathed his son an invincible army, composed of an infantry phalanx of superbly trained pikemen carrying 16-foot spears, and a powerful cavalry arm of expert horsemen. He also left Alexander with a mission— to lead a unified Greece in attacking and plundering the vast Achaemenid Empire to the east, finally avenging the attempted Persian invasion of Greece nearly 150 years before.

Alexander went far beyond his father’s vision, not just raiding and plundering Persia, but swallowing it whole. In three titanic battles, he routed a Persian army many times the size of his own and pursued the fleeing King Darius clear across his disintegrating Achaemenid Empire. When Darius was assassinated on the approaches to the distant province of Baktria by two of his own Satraps, Alexander kept on going in hot pursuit of the Great King’s murderers.

When Alexander crossed into Baktria in 330 BC, he was not yet 24 and had just smashed the greatest empire on earth with ridiculous ease, bringing all of Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, Egypt, Iraq and Iran under his direct rule. But the most difficult campaign of his career lay ahead. For the next three years, he marched back and forth across Baktria, often having to deal with revolts that sprang up in in the regions he’d supposedly pacified. His army suffered horribly from extreme weather and deprivation. The population proved even more hostile than the elements, adopting hit-and-run tactics much like those of the present-day Taliban.

Finally, after three excruciating years, the enemy leaders were killed and Alexander decided to declare victory and move on. He also hit upon a diplomatic masterstroke: He took to wife Roxane, daughter of a powerful Sogdian warlord, and encouraged his men to take Persian and Baktrian brides as well. He inducted thousands of native Baktrian warriors into his army, giving them a stake in his continuing conquests. After settling 13,000 of his veterans in the region and founding several new cities, including at least three called Alexandria, he crossed into India and fought his last great battle, a victory against King Porus. He had notions of continuing on, seeking the literal ends of the Earth, but his Macedonian and Greek soldiers refused to follow him. Heartsick and worn out, he made his way back to Babylon, where he fell suddenly ill and died at age 32 in May of 323 BC.

Funeral Games

With no successor but an infant boy and a half-witted brother, Alexander’s generals set to carving out spheres of influence within this brave new world. Within 20 years, the Macedonian Empire had split into three major and several minor kingdoms. The biggest of these, dwarfing all the others, was seized and held by the commander of Alexander’s elite bodyguard, Seleukos, Nikator (“Conqueror”), a crafty general and statesman par excellence. His realm sprawled from Syria and Phoenicia in the west all the way to the outskirts of India, and included all of Baktria. He reigned 30 years; his son and grandson, Antiochus I and II, reigned five decades more, spanning most of the third century BC.

With so much territory to control, the Seleukid kings adopted the old Persian system of governance and appointed local governors called Satraps, who had enormous authority in their provinces. Along with this came a certain amount of autonomy. As time went on, the Satraps of the most far-flung provinces became semi-independent potentates. It remained only for one or more of them to take “semi” out of the equation.

Rebel Satrap?

During this unsettled period, one of these Eastern Satraps, named Sophytes, struck coins in his own name, rather than those of his Seleukid overlord. It is not known whether this was an act of rebellion or whether he was just testing the limits of his authority.

His name, Sophytes, seems more Indian than Greek. In fact, a “Sopeithes,” possibly a variant spelling, is named by one of Alexander’s biographers as a northern Indian king who fought against the conqueror during the Indian campaign of circa 325 BC. The Sophytes coinage has been dated by various authorities to between 304 and 240 BC. Perhaps, late in his career, King Sopeithes came to an accommodation with the Greeks and was appointed a local Satrap of Baktria and Greek-ruled India. Or perhaps Sophytes was his son, or someone entirely unrelated.

Figure 2: Tetradrachm of Sophytes (Triton XXII, lot 445)

Coins of Sophytes fall into three groups: an immense number of Athenian-type “owl” tetradrachms of a distinctive Baktrian style, an issue of drachms and hemidrachms with an Athenian-style obverse and a standing eagle reverse, and a more limited issue with a distinctive helmeted male head on the obverse and a rooster and caduceus on the reverse.

The portrait coins carry the name Sophytes in Greek letters, without the royal title Basileos, or King. Silver denominations from tetradrachm down to obol are known, with tetradrachms and didrachms exceptionally rare. The rooster reverse is highly unusual for a Hellenistic issue; perhaps it is a personal badge. Taken together with the caduceus, wand of the messenger god Hermes, the rooster would seem to be bearing a message. In Greek mythology, the rooster is a symbol of the victory of light over darkness, the dawn of a new day.

Baktrian Breakaway

Around 250 BC, another Seleukid satrap of Baktria, a certain Diodotos, chose to put his own portrait on coins struck in his province instead of his ostensible sovereign, Antiochos II (261-246 BC). On the reverse, Diodotos employed a personal blazon, a striding figure of Zeus hurling a thunderbolt. Initially, Diodotos demurred from a full break from the Seleukid Empire, employing the name of Antiochos II on his coins.

A more recent theory by Jens Jakobsson proposes that the coins that appear to depict Diodotos with the name of Antiochos in fact belong to another independent Baktrian king, “Antiochos Nikator.” This theory has gained acceptance in some circles, but has been challenged by Brian Kritt in his book “New Discoveries in Baktrian Numismatics” [CNG, 2015], which employs a detailed die analysis to support the more traditional interpretation of these gold and silver issues.

We know very little about Diodotos, or about the kingdom he seized. He must have had a sizeable army in order to defend his realm against the Seleukids and the Parthians, who soon carved out their own kingdom southwest of Baktria. Eventually, the Parthian kingdom would occupy most of present-day Iraq and Iran, thereby cutting off the Greco-Baktrian kingdom from direct contact with the Greek-ruled west. This is one reason the Greek historians of the west make so little mention of Baktria in their writings – out of sight, out of mind, out of history.

Diodotus ruled jointly for some time with his son of the same name (Diodotus II), who eventually succeeded him in about 235 BC. It appears as though Diodotus II continued to strike coins with the portrait of his father, but with the family name of Diodotus replacing that of Antiochos on the reverse; concurrently or a bit later, the portrait of the younger Diodotus replaces that of the elder. But after roughly a 10-year reign, Diodotus II was overthrown by the satrap of Sogdonia, a man named Euthydemos.

Figure 3: Extremely rare posthumous silver tetradrachm of Diodotos I (Triton XXV, lot 556 ).

Euthydemos the Honest

Figure 5: Tetradrachm of Euthydemos I with young features (Triton XXII, lot 449)

Euthydemos presents an interesting picture of a ruler. We know three things about him—he was bold, he was honest, and he was stubborn. We know he was bold because he took the initiative to overthrow his overlord and make himself king. We can say he was honest, as least as far as his appearance goes, because he is one of the few rulers who actually ages on his coins. His early coins depict him as a relatively smooth-faced young man, as seen at left. By the end of his reign, he is the aged, care-worn fellow we see below.

As for stubborn, Euthydemos is mentioned by the second-century BC historian Polybius in his biography of the Seleukid king Antiochos III the Great (222-187 BC). According to Polybius, Antiochos decided to march east and reconquer all the lands that had been lost by his forebears. In 208 BC he arrived in Baktria, ruled by Euthydemos. The Baktrian ruler commanded a huge cavalry arm, more than 10,000 riders. But these were routed by the Seleukid army and Euthydemos took refuge in the city of Baktra, where he remained under siege for more than two years. Eventually, Antiochos wearied of the siege and cut a deal, allowing Euthydemos to retain power. His stubbornness had paid off.

Figure 6: Tetradrachm of Euthydemos with elderly features (Triton XXV, lot 552)

Polybius also mentions Euthydemos had a son named Demetrios, the next Baktrian king, who succeeded to the throne circa 200 BC. Demetrios wasn’t satisfied with holding just Baktria and Sogdonia. He launched a major invasion of India, probably about 190 BC, and conquered a huge swath of it to the north of the Peninsula. His coins show him wearing an elaborate headdress in the form of an elephant’s head, including trunk and tusks. This is not just a reference to his Indian conquests, but also an homage to Alexander the Great, the first Westerner to enter India.

Figure 7: Tetradrachm of Demetrios I (Triton XXV, lot 553)

Royal Pageant

After Demetrios, the recorded history of his successors almost disappears. We are forced to reconstruct what happened next from the coins alone. It does seem that Demetrios, while occupied in India, appointed his son, his brothers and perhaps other relations to rule Baktria in his stead. Perhaps they carved the kingdom up, perhaps they ruled the same lands by committee —we really don’t know. They all seemed to have ruled between 190 and 175 BC. In this Royal Pageant we have…

Euthydemos II (c. 185-180 BC), probably the son or younger brother of Demetrios, who was obviously quite young when named king and doesn’t age at all in his portraits. This and the scarcity of his coins indicate a very brief reign.

Pantaleon (c. 185-180 BC), whose portrait coins are exceptionally rare. His remarkable, fleshy portrait is backed with a seated figure of Zeus holding an image of Artemis holding two torches, a curious local variation on the king of the Olympian gods.

Figure 8: Rare tetradrachm of Pantaleon (Triton XXV, lot 555)

Agathokles (c. 185-175 BC), perhaps the younger, thinner brother of Pantaleon. His coins are more easily obtained than those of Pantaleon, though one can’t call them “common.” His portraiture is razor-sharp and he seems to have a bit of a mad gleam in his eye. Further suggesting a tie to Pantaleon, his reverse also shows a standing Zeus holding an image of Artemis light-bringer.

Curiously, the three rulers above struck a middledenomination coin in a metal nearly unknown to the Western ancient world: cupro-nickel. The only logical place this metal could have come from is China, where it was known as “white copper.” Surviving pieces usually have a rough, pitted appearance with inclusions of pure copper, suggesting the Greek mintmasters had trouble getting the nickel hot enough to properly alloy with copper. This, and the difficulty in obtaining nickel, is likely why the denomination was quickly abandoned.

Antimachos (c. 180-170 BC), who modestly calls himself Theos, or “god.” His coins are among the most amazing portrait pieces ever struck, depicting a rather self-satisfied and jovial-looking man sporting a peculiar Macedonian sun hat called a kausia.

Figure 12: Tetradrachm of Antimachos (Triton XXII, lot 461)

We haven’t said much about the reverses on these coins, but these are very important. The ruler usually puts his patron god or gods on the back, along with his name and titles. Antimachos depicts Poseidon, the Greek God of the sea, holding his trident. Yet Baktria was mostly land-locked, except for one corner that butted up to the Caspian sea, itself a big lake. One explanation may be that Poseidon is also the god of earthquakes, and these are rather common, and frequently devastating, in Afghanistan.

Apollodotos I (c. 180-160 BC), who is also depicted as aged and jowly. He could be a brother of Antimachos, as on his rare Attic-weight portrait coins, he is also depicted wearing the kausia. His area of control was likely centered in northern India because his small square silver drachms are commonly found there. He could thus be considered the first fully Indo-Greek ruler, although too little is known about his area of control to be certain.

Figure 10: Tetradrachm of Apollodotos I (Triton XXV, lot 558)

Demetrios II (c. 150-145 BC), possibly the younger son of Demetrios I, or of Euthydemos II, he seems to have attempted to solidify his rule over both Greek India and Baktria. For a few years he enjoyed success, but came to grief when he took on a usurper named Eukratides. The latter counterattacked, shredding the army of Demetrios, leading to his downfall and demise.

Eukratides the Great

Eukratides, possibly the son of a successful general and a Seleukid princess, built on this success until he deposed all rival rulers and absorbed their realms into his own. His first coins are relatively modest: Eukratides wears the simple diadem of a Hellenistic king and identifies himself only with his name and the title Basileos. The reverse type is distinctive: The heavenly twins Castor and Pollux, sons of Zeus, galloping on their steeds, holding couched spears.

Figure 13: Gold stater of Eukratides I Megas (Triton XVIII, lot 837)

As his conquests increased, his imagery and titles became more grandiose. On all his coins, he now wore an unusual helmet, a broad-brimmed variant on the Greek Boeotian helmet much like the pith helmets worn by British colonial officers of the late 1800s. On some of his coins he appears as a mighty Greek hero, heroically nude, with a powerful, muscled back, hurling a spear as Zeus would a thunderbolt. His title became Eukratidoy Megalou Basileos—“Greatest King Eukratides.”

If the sheer number of his coins are any indication, Eukratides was indeed “The Greatest.” His coins are found in a swath across Afghanistan and Northern India. Among them is the largest ancient gold coin ever found—A mammoth gold 20-stater piece, weighing 169 grams, nearly six ounces, and nearly 60 millimeters in diameter.

This gigantic gold piece was apparently found in 1867 by six Afghani men near the town of Bukhara. As in “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” the finders commenced killing one another – the six men were winnowed down to three, two, and one, who risked all to take his treasure to the center of the numismatic world, London.

The above story was provided by a French numismatist under contract with the British Museum. His name is now unknown, but he anonymously published an account of his discovery years later: As he was having lunch one day with some friends, one told him of an encounter with a shaggy beggar who tried to sell him an enormous gold coin which, of course, must be a forgery. He described the piece, and the Frenchman realized it might not be a fake. He tracked down the ragged beggar, who pulled out an old leather case and unwrapped the biggest gold coin the Frenchman had ever seen. And, being familiar with the amazing Baktrian coins starting to trickle out of Central Asia, he realized it had to be authentic.

The “beggar” demanded 5,000 pounds for the coin—an incredible sum in 1867, equivalent to about $600,000 today. The Frenchman calmly wrote out a check for 1,000 pounds and told the owner he had 20 minutes to think it over; after that, the price would go down to 800 pounds, then 500, and so on. The beggar scowled at him, then took the check and handed the Frenchman the coin. Although the Frenchman was supposed to be working for the British Museum, the coin ended up in the trays of the Biblioteque Nationale in Paris, where it resides today.

Other coins of Eukratides tout his family lineage. This tetradrachm has on the obverse the jugate portraits of his father and mother, Heliokles and Laodike. Note that Heliokles wears no kingly diadem—although he may have held a high rank, he was not a king. But you can just detect that Laodike is wearing a diadem—she may have been of royal blood, which is how Eukratides possibly justified his claim on the throne.

Eukratides also struck many bronze coins of a hybrid Greek-Indian design, including square bronze denominations with Indian Karosthi script on the reverse. This follows on from the earlier coinages of Apollodotus I, who began issuing parallel denominations—a heavier series of coins in the standard Greek denominations with Greek legends only, and a lighter, bilingual series of coins featuring Indian themes and deities.

Figure 14: Gold 20-stater piece of Eukratides I (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 15: Dynastic tetradrachm of Eukratides I (Triton XXII, lot 469)

Menander / Melinda

Eukratides seems to have ruled all of Baktria and associated regions west and north of the Hindu Kush. At one point, he seems to have crossed the towering range and entered the area of Gandhara. His control of this region was short-lived, however, and he appears to have been pushed out of northern India and Pakistan by another Greek King named Menander Soter (“Savior”). Menander is one of the only Greek kings to have entered Indian lore—in a Buddhist text called the “Melinda Panha” he is described as “learned, eloquent, wise and able.” The book claims him as a convert to Buddhism: “And as in wisdom Figure 11: Extremely rare Attic-weight Tetradrachm of so in strength of body, swiftness, and valor there was Menander I, aka “Melinda” (Triton XXV, lot 565) found none equal to Melinda in all India. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.”

Menander ruled more than three decades, circa 155 to 130 BC. His authority seems to have extended from Gandhara south of the Hindu Kush clear across India, as noted by Oliver Hoover, “as far east as the old Mauryan capital of Patilaputra and as far south as the Hindu Holy City of Mathura.” While not the first “Indo-Greek” as opposed to “Greco-Bactrian” king (that appears to be Apollodotos I), his reign did much to solidify and consolidate Greek rule in the region, which would continue at least another century and a half. While his Attic-weight silver

coins are extremely rare, with only three to five known specimens, his Indian-standard silver coins are abundant, indicating this part of his realm enjoyed a thriving economy.

But while the Greek kingdom of India throve, Baktria faced catastrophe.

Bad End

The one brief account we have of Eukratides’s life, by the Roman historian Justin, claims he reigned more gloriously than any of his predecessors, but came to a bad end. His wars eventually drained the treasury, leading to collapse and anarchy. Eventually he was murdered by his own son, who drove his chariot repeatedly over his father’s corpse, rending it limb-from-limb.

Archaeological evidence points to multiple invasions of the Baktrian Kingdom from all sides, starting right around 145 BC. The culprits are the Parthians in the West, the Scythians in the North, and the Yuezhi, Asiatic steppe nomads rather like the Huns and Monghols, in the East. Whether the assassination of Eukratides threw the door open to the invaders, or whether his death was a result of the frontier collapse, we can’t say.

Who was the murdering son? We have coins of three possible culprits— Eukratides II, who ruled briefly from about 145 to 140 BC; Heliokles I, who ruled a steadily shrinking realm from 145 to about 130 BC; and Plato, whose coins are the rarest of the three, reigning for a handful of years during the same span.

Plato’s rare coins depict a frontal view of a chariot bearing the sun god Helios on the reverse. Baktrian scholar Frank Holt has suggested this is an oblique reference to the desecration of Eukratides’s body, fingering himself as the parricide. This may be a stretch, but we have nothing else to go on.

Figure 17: Tetradrachm of Plato, son (and killer?) of Eukratides I (Triton XV, lot 1348)

The longest-reigning son, Heliokles, was the last Greek king of Baktria. He fought a rear-guard action against the invaders, but was finally overwhelmed between 130 and 125 BC. The invaders, though, absorbed Greek culture and produced coins that combined Greek, Parthian and Indian motifs. This polyglot culture survived for some centuries, eventually becoming what we now refer to as the Indo-Parthian and Indo-Sasanian cultures.

Indo-Greek Afterglow

This was not the end of the Greek orient, however. Greek rule beyond the Hindu Kush, in Gandhara, the Punjab and other regions of northern India, continued for at least another century and a half. After Menander, the Northern Indian kingdom seems to have fragmented. We have coins of literally dozens of kings, and in some cases queens, many of whom must have ruled concurrently. These rulers generally stuck to a specialized hybrid Greek-Indian form of coinage based on a silver tetradrachm weighing about 9.5 grams, drachms of roughly 2.4 grams, and bronzes of several denominations, several of them square. The obverse legend naming the king or queen is in Greek letters, while the reverse repeated this in the Indian alphabet Kharosthi. A future article will deal in-depth with the Indo-Greek and other kingdoms of ancient India.

Although both the Indo-Greek and Indo-Skythian kingdoms were eventually absorbed into the native Indian dynasties, and eventually the Kushan Empire, their fusion of Greek and Indian culture proved durable. The Greek model of coinage, including portraiture and Greek legends, were incorporated by the Kushan and Gupta rulers of India that followed. The serene faces of Buddha and Maya and the deities of the Hindu pantheon found in classic Indian sculpture carry clear echoes of the Apollo, Cybele and their Greek cousins, down to this day.

Collecting the Coins

Greco-Baktrian coins were struck in gold, silver, cupro-nickel, and bronze. In general, the coins are widely available in the numismatic marketplace. Some rulers, like Eukratides and Menander, are commonly found in both print and online auctions, as well as dealer stocks and fixed price lists. Other rulers are much rarer and more difficult to find. Assembling a complete or nearly complete ruler set would be a major accomplishment, but by no means impossible.

tetradrachms of the more common Baktrian or Indo-Greek kings can be had for as little as $300, but rare rulers in high grade can fetch $50,000 or more. Small denomination silver coins and bronzes, however, are rather neglected by the collecting public, and even rare and attractive examples can be obtained for well under $200.

As noted repeatedly before, the portraiture found on the earlier Greco-Baktrian coins is the finest of any Hellenistic series. The superb execution, the inventive bust types and the evocative reverses all testify to the great skill of the engravers and mint masters in these far-flung regions. A carefully assembled collection of coins from these Empires of Mystery, arrayed on one or more trays, is truly a sight to behold.

TABLE OF GRECO-BAKTRIAN RULERS

Rarity scale (applies to coins in Good VF to EF condition):

Common – Regularly appears in internet, print and public auctions. Gold coins usually available under $5,000, silver coins available under $500, bronzes under $200.

Scarce – Occasionally appears at auction. Gold coins available for a minimum $10,000, silver coins $1,000, bronzes under $300.

Rare – Seldom appears at auction. Gold coins typically over $10,000, silver coins over $1,500, bronzes over $500. Very rare, Extremely rare = Each step approximately doubles value.

Many rulers also struck special issues with different obverse and reverse types that can be of considerable rarity.

Portrait Ruler

Sophytes

Diodotus I

Reign

Satrap (?) c. 280/78270 BC

C. 255-235 BC

Diodotus II C. 235-225 BC

Euthydemos I C. 225-200/195 BC

Rarity

Silver non-portrait: Scarce

Silver portrait: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Gold: Scarce

Silver: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Gold: Rare

Silver: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Gold: Rare

Silver: Scarce

Bronze: Scarce

Demetrios I C. 200-185 BC

Euthydemos II

C. 185-180 BC

Agathokles C. 185-175 BC

Pantaleon C. 185-180 BC

Antimachos I Theos C. 180-179 BC

Apollodotos I C. 160-155 BC

Antimachos II C. 160-155 BC Gold: Very rare

Silver: Scarce

Bronze: Common

Silver: Rare

CU-NI: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Silver: Rare

CU-NI: Scarce

Bronze: Scarce

Silver: Extremely rare

CU-NI: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Silver: Scarce

Bronze: Rare

Silver portrait: Extremely Rare

Silver drachm (nonportrait: Common

Bronze: Common

Silver drachm (nonportrait): Common

Bronze: Rare

Demetrios II C. 150-145 BC Silver: Rare

Eukratides I Megas C. 160-155 BC Gold: Rare

Silver (diademed portrait): Rare

Silver (helmeted portrait): Common

Silver dynastic: Rare

Bronze: Rare

Eukratides II C. 145-140 BC Silver: Scarce

Plato C. 145–140 BC Silver: Extremely rare

Heliokles I C. 145–130 BC Silver: Scarce