The Cantuarian

Front Cover: Amelie Board (6b, MR)

Front Cover: Amelie Board (6b, MR)

Front Cover: Amelie Board (6b, MR)

Front Cover: Amelie Board (6b, MR)

The Captain’s Speech Ludo Kolade 6

The Chaplain’s Chapter Lindsay Collins 8

Galpin’s House Michael Boyne 10

Fields of Gold Trajan Majomi 14

Proust Uncut Sophie Sy-Quia 18

A Glass Act Naomi Cray 20

Purple Patch Purples 24

Shell Shock Shells 28

Novel Advice A. F. Steadman 34

Milk and Sleep Briony Cobb 40

The Maker’s Tale Peter Pinder 44

Hard Graft Gavin Merryweather 48

Writing Music Annalise Roy 52

Football Fanatic Rob Harrison 56

Buzz Cars David Perkins 58

Play it Again Roberta Mak 60

Chasing Legends Maddie Aldag 62

Dancing Queen Elina Lin 66

FREDIE FREDIE 70

Wisdom Teeth Charlotte Lester 78

Bred in the Bone Lilia Trigg 80

Earthy Secrets Ross Lane & Jess Twyman 84 Yes, Chef! Andy Snook 90

The Long Ranger Fede Elias 92 Faith Natalya Hoare 94

Salvete Prize Annika Li, Dylan Shearer & Molly Jones 96 Daybreak Song Finn Cleghorn-Brown 102

Sport Jack Pelling & Lucy Andrews 106

Music Lucas Emmott 118

Drama Imogen Melrose 124

From the Archive The Cantuarian 1922 136 King’s Week 144 Art Exhibition 150 Valete 156

Editor Anthony Lyons

Photographer Matt McArdle Designer Cobweb Creative Archivist Peter Henderson

Cobweb Creative yvonne@cobwebcreative.org

Matt McArdle Photography mattmcardle13@mac.com

The Cantuarian info@cantuarian.co.uk

At last, we’ve managed to publish The Cantuarian in the right calendar year, because pupils, staff and OKS rose to a fresh challenge after years of frustrating delays. What follows is, of course, largely a tribute to a constructive decade of leadership by a memorably erudite, industrious and architectural Headmaster, Peter Roberts, who set the school magazine free and allowed it to take new paths and break new ground.

‘We hope you’ll agree that the following pages capture once again a unique school ethos.’

We hope you’ll agree that the following pages capture once again a unique school ethos. King’s is a centre of learning without snobbery, prejudice or arrogance. The word ‘culture’ is never used at this school to mean decorative or recreational activities, because it knows that culture is merely what distinguishes humanity from the biology we share with other great apes.

At King’s, culture is not just art, music, theatre or literature, but also sport, mythology, religion, languages, science and philosophy, and every other activity that chimpanzees and bonobos do not practise. At King’s, rugby is no better than chess, painting is no better than computing, and debating is no better than praying. Human curiosity, enterprise and the pursuit of excellence inspire us all. And it’s a cultural melting pot as a result, since 74 different nations this year have sent their sons and daughters here to learn how to feel, think and behave like adults. Yes, King’s pupils are no longer suppressing emotions but learning to air them openly and steer them creatively, rather than pretending rationality is still the Holy Grail.

How humbling it’s been putting this issue together. A boy born in Kyiv explains why 2022 has been tough. A girl stumbles across an uncut edition of Proust on a classroom shelf and gets it cut. Another girl tells us which stained glass windows in Canterbury Cathedral she likes best. Purples reveal their ambitions for later life, and Shells give advice to their would-be successors from prep schools. An award-winning OKS tells pupils how to write a novel without going mad; another explains how to bring up a child according to nature; and another charts an astonishing career living on his wits in the Far East.

And the school staff prove they are much more than their jobs suggest. The chap who runs the place, the land and buildings on which we all depend, is an Iron Man. The accompanist at Congers is a gifted composer. The indefatigable young polyglot in Modern Languages is a soccer nutter. And the brilliant History teacher, who could easily live in the past if he so chose, is fully aware of the way the past affects the present and our global future day by day. If that’s not enough, a renowned pupil pianist, who plays entire Chopin polonaises from memory, celebrates her father learning the piano, aged 72. Also, a daughter celebrates her father’s brilliant career as a cyclist, and a god-daughter celebrates the dancing genius of her godmother, the greatest of all Chinese ballerinas. I could go on, but do read for yourself.

If you have any ideas for future issues, please get in touch.

Anthony Lyons Editor info@cantuarian.co.uk

Anthony Lyons Editor info@cantuarian.co.uk

ood afternoon, everyone.

My most recent experience of Shirley Hall has been frantically scribbling for my A’ Levels, so I can only say I’m delighted to be back here instead to celebrate the end of school, surrounded by my friends and family.

The Captain of School’s speech is certainly an intimidating task. I wondered whether to compose a speech filled with life-changing bits of advice, the sort of speech that would be spoken about for years to come. But I’m only an 18-year-old boy, so this afternoon I decided instead to talk from the heart about my experience of King’s, a school which to me has meant very much over the past five years.

I remember the first time I was hit by the King’s spirit, the first time I understood what it meant to be a King’s pupil, was House Song in Shell. Now for those who don’t know, King’s House Song is perhaps the most fiercely competitive event of the calendar year. Rivalries are formed, friendships are put to the test, and I will not even dare mention what goes on if two houses happen to choose the same song! But I still vividly remember approaching Shirley Hall for my first House Song and immediately I was hit by this wall of sound of houses chanting, and singing, and enjoying themselves. This highlighted to me just what we are as a school – passionate. I believe this is what makes us unique compared with other schools. We are passionate about everything we do, from art, to drama, to sport, to music, and we celebrate the success of

those on the cricket pitch just as much as we do the success of those on the stage or in the science labs.

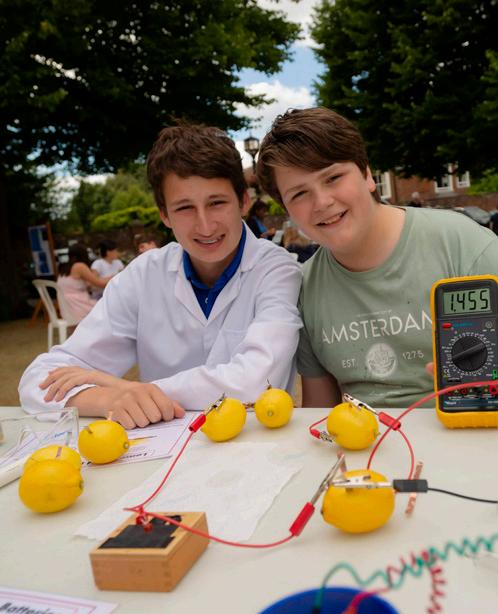

Now this year marked the 71st King’s Week, and being able to welcome parents back into the school has been fantastic. But for me the return of King’s Week proper epitomises all that King’s is: a joyous, inclusive, and fantastically talented community. Whether you went to see Elliot amaze us all at the jazz, or Max take to the stage in Twelfth Night, or perhaps you were even lucky enough to see Louis Smeeton sporting a particularly dashing tank top at Fleetwood Mac, what I’m sure we can all agree on is that not only has the standard this year been exceptionally high, but to be able to relax, and enjoy, and celebrate amongst friends and family has been extraordinary, and something we have not taken for granted.

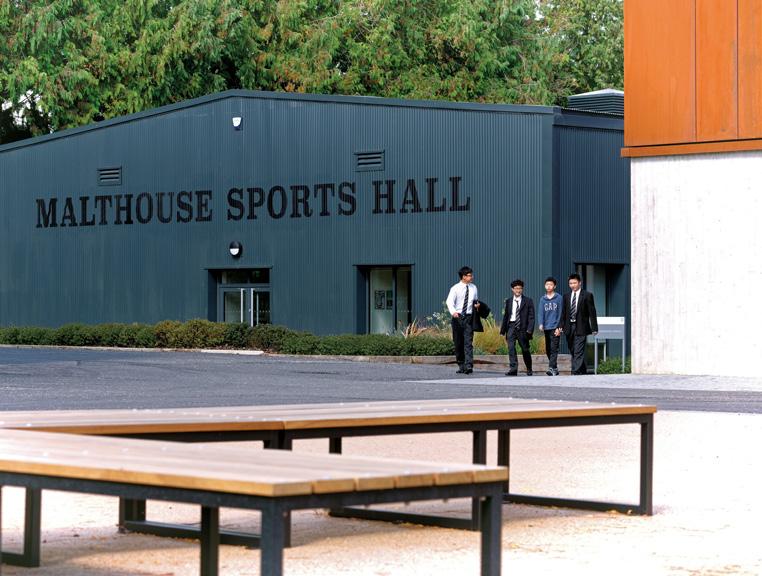

Sadly, the end of this year’s King’s Week also means we must say goodbye to the Headmaster and Mrs. Roberts. The Headmaster joined King’s in 2011, and in his time here he has taken this school on in leaps and bounds. He has spearheaded projects such as the Malthouse, opened international colleges in Shenzhen, Cambodia, and right here in Canterbury, and set up the new science block. This is all the more impressive when you consider that he did all this alongside a strict seven-day-a-week training regime for the Paris marathon. Ultimately, the Headmaster’s ability to be fun and himself, with frequent ramblings in either Latin or French, which still to this day we do not understand, allows each student to be themselves too, and for that he will be sorely missed. Alongside

‘What I’m sure we can all agree on is that not only has the standard this year been exceptionally high, but to be able to relax, and enjoy, and celebrate amongst friends and family has been extraordinary.’

‘I’m only an 18-year-old boy, so this afternoon I decided instead to talk from the heart about my experience of King’s, a school which to me has meant very much over the past five years.’

him is Mrs. Roberts, who is not only a massive support to the Headmaster, but a quiet leader herself. I am also told she is a fantastic harpist (there you go: don’t say this speech didn’t teach you anything). Mr. and Mrs. Roberts, on behalf of everyone here at King’s, I would like to say a massive thank you and wish you the very best for your retirement.

I would also like to thank the Senior Leadership Team - Mrs. Worthington, Miss Lee, Mr. Bartlett and Mr. Hunter, whose relentless efforts have navigated the school through the pandemic so successfully.

And now, the 6a’s. I would like to thank my friends and the whole of the 6a year group. For our year to have so many individuals excelling in different areas is a truly impressive feat. This ranges from Henry and Octavia raising thousands of pounds for various charities, to Funbi and Melissa spearheading FREDIE groups promoting racial and sexual equality, to Maya performing with the Chineke Junior Orchestra at Soccer Aid in front of 60,000 people. But perhaps more impressive still has been our year’s ability to pull together despite the challenges of the pandemic. How many hours must we have spent sat in our

bedrooms in front of a screen? More likely, how often did we set our alarms for 8:59am to roll out of bed for our 9am lessons? But to be able to come through such a tough period and then complete our first-ever public exams, I think, is truly incredible, and something we should be very proud of ourselves for. This resilience, to persevere despite what is going on around us, is what has prepared us so well to tackle challenges head on, and why we should be excited about whatever the future holds for us.

‘The Headmaster’s ability to be fun and himself, with frequent ramblings in either Latin or French, which still to this day we do not understand, allows each student to be themselves too, and for that he will be sorely missed.’

I would like to finish with a quote from OKS, Michael Morpurgo, which reads, ‘If I learned anything in life, I have learned that you can’t cling on.’ So, this would be my final message to all of us: whilst this chapter of our lives is now over, take confidence from what we have learnt and achieved here at King’s. Use those experiences to tackle whatever obstacles we face in our future, and celebrate both what has been and what is to come.

King’s Chaplain, Lindsay Collins, muses on the holiness of hospitality.

King’s Chaplain, Lindsay Collins, muses on the holiness of hospitality.

Having had the privilege of serving as Chaplain of The King’s School for the past five years, and looking forward to beginning my sixth year in this special community, I find myself reflecting on what has made my time here so fulfilling. It is easy to comment on our awesome students, the friendliness and hard work of the committed staff, or even the beautiful setting in the Precincts of Canterbury Cathedral. But overhearing some wedding guests enjoying the exceptional food and service of our wonderful catering department during the summer holidays, I realised they had articulated exactly what it is: ‘The hospitality of The King’s School is second to none,’ they said.

And in that one word, ‘hospitality’, they summed up for me what is the ethos of The King’s School and what underpins everything else that goes on here. I should not be surprised, because hospitality has been the bedrock of Christianity in Jesus’ golden rule of love for God and for our neighbour. Hospitality was also practised for centuries by the monks on this very site, who followed the rule of St. Benedict that required them to welcome the guest as Christ himself.

The Israelites in the Old Testament were constantly reminded to ‘welcome the stranger because you know what it is to be a stranger in a foreign land’. The richness of The King’s community comes from the diversity of our members and we welcome students from across the globe. Over the past year staff and students have formed a range of committees to find ways of ensuring we show all who come through our door the best hospitality that we can, because true hospitality matters in a community. As the former Archbishop, Rowan Williams, wrote: ‘Hospitality invites the stranger to come into our own safe space and thereby turns the place of safety into a place of risk. Hospitality is an adventure that you have without travel. Hospitality implies and requires the questioning, stretching

and maybe transgressing of the boundaries that make our life orderly, predictable and pleasant. True hospitality lets things get under your skin.’

In preparing King’s students for the unpredictability and constantly changing nature of the world, hospitality becomes a key skill that they need to have encountered and practised themselves. In learning to make room for the other, they allow themselves to be open and hospitable to new ideas, different cultures and beliefs, alternative ways of seeing and of being.

Such understanding will only help to create people of peace and justice in our world. As Letty Russell wrote: ‘Hospitality is the practice of God’s welcome by reaching across difference to participate in God’s actions bringing justice and healing to our world in crisis.’

In order to practise hospitality we need to learn to make space in our lives. In a world of continued busyness, a lesson we all took away from lockdown was the appreciation of space, of stillness and of silence. Whilst we missed social and tangible interaction, we recognised that making space for reflection, for new ways of living, for discerning what is truly important in our lives, is a necessary part of our development. It is perhaps why students so enthusiastically embraced the introduction of a 9pm midweek voluntary service of Compline in school, for it creates an opportunity for them to reflect on making space in their lives for the things that matter: friends and family, love and justice, fun and joy.

The writer to the Hebrews was inspired when he wrote, ‘Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.’ My prayer for The King’s School is that it will never lose sight of the importance of

for the stranger, whoever and whatever that

love

stranger might be.

‘‘In that one word, ‘hospitality’, they summed up for me what is the ethos of The King’s School and what underpins everything else that goes on here.’’

‘In preparing King’s students for the unpredictability and constantly changing nature of the world, hospitality becomes a key skill that they need to have encountered and practised.’

‘Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.’ (Hebrews 13:2)

The campfire burned brightly in the peaceful garden. I laughed and exchanged stories with friends, happy to be part of this community known as Galpin’s. Galpin’s is a place that I can call my home and holds many memories because of the amazing people who live there.

Galpin’s is located right at the centre of the school, and I’ve found this convenient for sleeping in when I’m lazy, and inviting friends over from other houses during breaks. It’s also close to the Music School, which has motivated me to improve my clarinet skills. While the location is a huge advantage to being part of Galpin’s, the most important part of the house is the people.

When I arrived in Shell, I was intimidated by the new environment. It was my first boarding experience and I was extremely homesick. The addition of the independence required at a boarding school made me incredibly nervous. To be honest, I was considering asking my parents to let me leave the school. However, I soon found out that many people were struggling with the same problem, which made me feel less alone. I finally got the courage to start talking with the people in my house and realised I was worried about nothing, because these people would end up being my best friends. They have helped me through tough times at school, and were always supportive when I needed them.

The Sixth Form when I was in Shell were also intimidating to talk to, but over the course of the year I came to understand that the Sixth Formers are also teenagers, at the end of the day, and were just as immature as us. The Shell monitors from 6b would end up talking to us a lot, giving us advice or just messing around in house.

Galpin’s is known for its competitiveness when it comes to school events. We have won the overall House rowing cup every year since 2010, and we won the sailing cup every year from 2011-18. At the moment we have boys in many 1st teams (ranging from rugby to rowing, cricket to tennis, chess to fencing), and we are well known for being a very musical house (we have 3 pianos in the house).” During House Song, our conductor will always put their heart and soul into the piece they arrange, which encourages all of our house to try its best and win. It also gives us a role model to look up to.

One of the highlights of the summer term is the Galpin’s Garden Gig. This is held on the 3rd Sunday of the Autumn term and is viewed a little like a mini King’s Week! In the morning we move the sofas and chairs into the garden from our common room, and we put the King’s Week deck chairs onto the lawn, all facing our table tennis terrace. There are gazebos and food and drink on offer (all free!) and everyone

‘Galpin’s is a place that I can call my home and holds many memories because of the amazing people who live there.’

Michael Boyne (5th, GL) told us he was proud to live in Galpin’s, and we asked him why.

in the school is invited to join us, either on stage as singers and musicians, or in the audience. It is a really fun afternoon. I clearly remember Louis, Elliot, and Maya Moh from last year entertaining us for a solid two hours. This year we had Giorgio, Seb, Will, Flore, Mr T and more. Seeing everyone happy and having a good time on a sunny day in our garden made me really proud to be in Galpin’s.

Another thing that separates Galpin’s from other houses is that we have a brilliant housemaster, Mr. Sanderson. He has supported the house greatly when it comes to making school life enjoyable. By providing many types of entertainment, such as a PS4, a football table, darts and a movie night, every so often he has brought together many different year groups and made the house more alive. Whenever someone needs moral assistance, Mr. Sanderson is always available, willing to talk and give advice.

Other staff in the house also play a huge role in why Galpin’s is remarkable. Every cleaner and matron is very friendly. Our talks range from school-work to embarrassing stories that make us all laugh. Sadly, our matron, Michelle May, is leaving in a couple of months. She has brought joy into our house and cheered everyone up just with her presence, and never failed to resolve issues within the house. Even though she is leaving, she will still be fondly remembered and part of Galpin’s.

Galpin’s will always be a home to me. My fondest times belong in this house and it is the reason why I enjoy school so much. I need to make sure that I use my remaining two years at King’s wisely, because the cheerful, chaotic atmosphere of Galpin’s is something I don’t believe I’ll be able to experience again.

‘My fondest times belong in this house and it is the reason why I enjoy school so much.’

‘Whenever someone needs moral assistance, Mr. Sanderson is always available, willing to talk and give advice.’

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I never believed there could be such a conflict in my lifetime. I recall long summers with my grandparents in their village outside Kharkiv, and attending elementary school close to the city centre. I remember the Ukrainian people. I remember friends, parents of friends, teachers and my family. These days, I turn to memories of Ukraine for comfort when current affairs cause turbulence in my life.

It is because of these sacred memories that seeing footage of familiar buildings reduced to rubble is difficult. On the second week of the invasion, I woke up to a video of the town hall under heavy shelling. The town hall stands at the top of what is known locally as ‘Freedom Square’ in the city of Kharkiv. It is the cultural centre of a fine town with many universities and historic buildings. I once attended classes in a building across the street from the site of the impact, and daily drove past the town hall.

That video made me understand that the Russian tactic is to weaken and disorientate the Ukrainian people however possible, even if it means destroying the culture, morale and

emotional integrity of innocent civilians. While I find losing something at a distance difficult, I struggle to understand how people can witness and withstand such terror and horror firsthand.

I often think of my aunt and uncle, who live in Kharkiv. A few days before I was leaving the town to return to school in England last summer, I talked to them about when we would see each other next. While sitting outside their new home, we made plans. Now, in all likelihood, we will not see each other for months or even years. The freedom to roam they took for granted after years of living in the same city has been replaced by the confines of their basement, now their constant shelter from shelling. The images and sounds they have shared with the rest of the family are deeply haunting.

In the past, I wondered how victims of war cope with loss. After hearing accounts of the war from my friends and family I now see that such perils make victims feel any form of retaliation is fit and necessary. After days of confinement to her basement shelter, I shared an emotional phone call with my aunt, who was starting to feel the effects of living in

cramped space and hearing

Trajan Majomi (6b, TR) was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 2006. He explains what life has been like since February 2022.

a

constant

‘I recall long summers with my grandparents in their village outside Kharkiv, and attending elementary school close to the city centre.’

artillery fire. Her form of retaliation had to be mental and emotional resilience, which proves difficult to maintain when the shelling is nonstop.

My grandparents, who were abroad during the invasion, struggle to come to terms with their displacement. Based on my time in Ukraine, I believe that Ukrainian values centre on routine and role fulfilment. Like other Ukrainians of their generation, my grandparents grew up valuing a nuclear household. In my eyes, these values offer stability and safety, both difficult to find in war.

During the Easter holiday I visited my grandparents and tried to be a supportive grandson. I tried to be sensitive and considerate, especially after they received news from home that was not good news. While this was a turbulent period for them, they seemed positive and optimistic. To my surprise, they had even maintained their daily routine and diets. The endless meals to fatten me up, coupled with my grandfather’s never-ending list of anecdotes, made

‘It is because of these sacred memories that seeing footage of familiar buildings reduced to rubble is difficult.’

that visit feel like any other visit, and I realised this maintenance of routine by my grandparents was the only way they could cope with being barred from their country and their cherished home. But behind these attempts to cope, and their seeming optimism, there was fear and anxiety with every video from the front lines and every phone call from a friend in the know.

By sharing this account, I am trying to convey the effect the war has had on my family. I am lucky that none of those close to me have suffered fatally, and I hope this will stay the case, not only for myself but for others as well.

I hope also the conflict in Ukraine will be the last of its kind, and that with the end of this war humanity can move forward and abandon the mentality that causes leaders of nations to engage in such devastating behaviour.

‘The freedom to roam they took for granted after years of living in the same city has been replaced by the confines of their basement.’

‘Behind these attempts to cope, and their seeming optimism, there was fear and anxiety with every video from the front lines.’

‘She was both disappointed and excited to see that the pages of the book were uncut.’

One day, during an English lesson in the Maugham Library, Sophie Sy-Quia, who is bilingual in French and English, spotted a copy of Proust on the shelves but, after a crafty peek, she was both disappointed and excited to see that the pages of the book were uncut. When her English teacher saw the unsullied text, of course he called in the School Archivist, Peter Henderson, who not only supplied his own paper knife so that Sophie could cut open the pristine volume and have a good read, but also gave us the following details about her discovery:

Marcel Proust’s À L’Ombre des Jeunes Filles en Fleurs was the second volume in his sequence of novels À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. It was published in 1918 and won the Prix Goncourt.

In the Maugham Library are two of a three-volume set published in 1934. The cover states this is the ‘145e édition’ and the cost is 45 francs per volume. These particular copies did not belong to Maugham but were part of a collection of books given to King’s by OKS Bruce Money.

The pages were ‘uncut’ because each group of eight pages was printed on one sheet of paper and then folded and bound. The reader would therefore need to use a paper knife, or a letter opener, to cut open the pages at the top and the side. (Or, as was not uncommon in the 19th and early 20th Centuries, give it to a bookbinder to be trimmed and bound.)

The King’s School Library has most of the French volumes in a 1954 edition, as well as the Penguin complete Remembrance of Things Past (in the CK Scott Moncrieff / Terence Kilmartin translation) from 1983. So no need for that paper knife.

Those who want a quick Proustian fix might even try the Gallic Press’s ‘graphic novel’ version: In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower published in 2019 that runs to just 112 pages. [But not in the Library.]

This is what happened when A’-Level English student, Sophie Sy-Quia (6a, BR), stumbled across a text in French on the shelves of the Maugham Library.

Canterbury Cathedral contains over 1,200 square metres of stained glass depicting inspirational stories of men and women that relate to the history of the Cathedral and its community, as well as British saints. It is thought to be amongst some of the oldest in the world, according to the latest research, and is one of Europe’s largest collections of early medieval stained glass.

The Miracle windows are in the Trinity Chapel, on the north side. The eastern-most window, half-way up on the left side, depicts the story of Mary of Rouen (formerly thought to be Mad Mathilda of Cologne). Dating from about 1213, the Miracle Windows show ordinary men and women going about their lives, some suffering from physical or mental illnesses, before being cured through divine intervention or benevolence. Mary, a citizen of Rouen, suffered from violent mood swings, and was healed after a visit to the tomb of St. Thomas Becket. Here she is shown in one of her ‘dancingaround-mad-with-hilarious-joy’ phases (to be followed by collapsing in a heap of despair) – what might today be called bipolar disorder. The two men either side are subduing her with bundles of sticks –more of a visual signal that this is a mad person than actual treatment at the time. Its inclusion in the Miracle windows is somewhat obvious; Mary’s story is relatable to many of the pilgrims since they too would have been seeking a cure for their ailments.

In the North Quire aisle, at Triforium level, above the right-hand Bible Window, the Siege of Canterbury is depicted, likely based on the story of St. Alphege. The window itself dates from about 1180, whilst

Given the profusion of fine devotional art on our doorstep, we asked Naomi Cray (6b, KD) to tell us about her favourite stained glass in Canterbury Cathedral.

the Siege of Canterbury itself took place in 1011, almost a hundred and seventy years before its completion. An eyewitness account of the event makes chilling reading and would probably have been known to the artist who designed this panel and influenced several of the design choices. The details shown on the window are graphic and dynamic – a lance piercing the chainmail of the soldier on the left whilst the people in the town are lobbing large lumps of flint at the attacking Danes. The Siege of Canterbury is shown on the cathedral for several reasons: the Vikings entered the city and held several influential religious figures hostage, as well as burning down parts of the cathedral. They were, however, unsuccessful at holding the town, and nor could they raise a ransom for the Archbishop. The Siege is shown because it proves that the spirit of community in the town will always overcome adversity.

Also in the North Quire aisle, on the left-hand Bible Window, at the very top, is The Magi Following the Star, from 1178. It shows the three wise men (known to medieval viewers as Magi) on horseback, travelling towards Bethlehem. These horses appear to be great beasts trotting boldly, but they are quite small compared to their riders. This is true of medieval horses – they were small, about the size of a Welsh pony. The agitation of the Magi so close to their goal is palpable – two are pointing passionately in the direction of Bethlehem, whilst the other has his head turned over his shoulder, looking back at his companions. This scene is probably included on the window because it is very recognisable, as well as relating to pilgrimages – something the Cathedral would want to show near the shrine of Thomas Becket because it would have been seen by so many pilgrims.

‘Dating from about 1213, the Miracle Windows show ordinary men and women going about their lives, some suffering from physical or mental illnesses, before being cured through divine intervention or benevolence.’

‘An eyewitness account of the event makes chilling reading and would probably have been known to the artist who designed this panel.’

We asked the 2022 Purples what they want to be when they grow up.

I want to be a neuropsychologist.clinical Yes, I am a nerd, but I will have the privilege of reading people’s minds. I hope to do this through studying Psychology at university, then progressing with a masters in Neuropsychology and a PhD in Clinical Psychology. Not to sound creepy, but I am excited to open up a brain. I have always been intrigued about activity in the brain and how this affects human behaviour; most of the time I don’t know what goes on in my brain, so I may as well figure out what goes on in other people’s.

Emma Stewart

Every morning when I leave the Linacre front door, I think of Nelson walking into that same drive to see Lady Hamilton. I look up at the orange stones in the ruined infirmary, caused by fire in 1174. I step into the Dark Entry and look across at the cathedral water tower; built in the 1160s, it is one of the oldest plumbed water systems in the world. I step onto Green Court. It is a frosty Autumn morning, and I can smell bacon. There is just time for breakfast before my History lesson. I think I may be working too hard.

George PaineI hope that my future self will look back and feel proud of how fully I have lived my life. This starts with a gap year when I will catch up on sleep… no, sorry, I mean do work experience, but also do the fun stuff like travelling, partying and making new friends. I am interested to see where a History degree will take me (I have no clue) but hopefully I will survive uni and then land a good job or possibly go to law school. Then maybe have a family? Or maybe just live with my 10 cats… To be honest, I don’t think the details matter, though, because whatever I do I won’t have any regrets. I will have taken risks and made mistakes but I will be happy knowing that I have experienced everything that I could possibly have wanted.

Anoushka Durham

I want nothing more than to be on the stage. Awaiting decisions for my drama school applications makes me fuelled with excitement for what hopefully may be to come. But, of course, this is a risky plan and a degree in Political Science, for which I have a few offers, gives me an alternative career direction to pursue. Nevertheless, a theatre company that works with primary school children focusing on confidenceboosting and their development is how I want to set up my own business. That is, of course, after my own time in the professional industry, working with like-minded people and creating art. Perhaps my ambition is bigger than reality sees fit!

Daisy LedgerI have chosen to study Physics at university because it is the field that I find most exciting, and it also leaves many doors open for me. There are several career pathways a Physics degree would enable me to pursue, such as Engineering, Computer Science or even Finance. However, continuing with my education after my undergraduate degree and potentially going into academia and research currently appeals to me the most. There are many branches of Physics being researched as it is a very broad subject. My time at university will help me decide what I’m most interested in.

Oluwole DelanoI want to be a Vexillologist (a studier of flags). A Geography degree is only the first step for me; the bulk of my study during my youth shall be via playing Fifa in my room until ungodly hours. This may be a solitary lifestyle, but in the long term it’ll make a heck of a party trick and, who knows, maybe the potential future Mrs. SB will be a flag-follower like me. People often tell me I’m only in it for the money, but it’s more about the history. Flags aren’t just about shapes and colours, you know. Each one has its own meaning. I don’t think I can ever learn enough in this study; flags are ever-changing. However, maybe there will be a day when we are all united under the same flag (hammer and sickle) and I can put my feet up knowing that there is no more for me to learn.

Nelson Standley Barrow

Nelson Standley Barrow

I want to be a creative when I grow up. Now I know that sounds incredibly abstract and borderline pretentious but ever since I was a very young child, I’ve always found it cool that an idea in someone’s head can materialise into something tangible. I wanted more than anything to be able to do that myself. In keeping with my cringe theme, I believe everyone should follow their dreams because you only get one chance at life. So, I’m taking the most realistic root for me to reach that goal, which is through music. Music is my main passion, and success in music will give me the platform and freedom to convey my thoughts, emotions, and experiences through whatever medium I feel like. And bring in lots of money.

Tobi AderibigbeMy dream is to be at the forefront of innovative veterinary medicine and all of its seismic advances.

Yes, I want to work with animals in the traditional veterinary sense – muddy fields and dirty hands – but

I also want to do more. I am spending the first three months of my gap year on an internship with Chester Zoo, as part of their exotic birds team, and then I am setting off to Southern Africa for the following six months to, hopefully, gain my safari game driver’s licence. I hope to be able to dip my toes into each and every part of the exciting world that is veterinary medicine. So, following my interview for the university of Nottingham, which I hope goes well, I will be starting my journey within a field of science which offers a lifetime of challenge and fulfilment. Ellie

DeanI have applied to study Economics at university. And no, my reasoning doesn’t stem from tucking into countless Economist magazines as a child or stumbling upon the movie Moneyball. It’s much more organic than that. Growing up in Nigeria, I experienced the devastating irony of a country developing quickly but still ridden with issues like mass poverty. For my whole childhood it seemed like the country always took one step forward but two steps backwards. So that’s why I’m striving to become a public finance economist – simply to help the country finally move in one direction.

Kamsi UzombaI’m uncertain of what I want to do. I would love to own by own design house, creating furniture, clothing and everything in between. I would also love to do advertising or work in the creative sectors of large firms. A degree in some area of art or design, after my foundation year, at Central St. Martins is the dream. Earning money for something that I enjoy doing would be pretty insane, being able to afford a multitude of houses in different countries and just keeping up with my own spending habits. But that’s only possible if I can eventually decide what I actually want to do!

Lili Clifton

Lili Clifton

I want to be a venture capitalist. Yes, in short, I am happy selling my soul for a handsome pay cheque at the end of each month. I am going to Bath University to read Economics, hoping to gain a better understanding of what makes the financial world spin. Perhaps, however, I will have a sudden change of heart, develop a sense of morality or, more likely, the grey drizzly London skies will finally take their toll, in which case I wouldn’t mind jetting off to South America to pursue a career in rugby (and work on my salsa!).

Ludo Kolade

King’s is an awesome place. King’s is a brilliant place. King’s is a big place. But most importantly King’s is not a scary place. King’s may seem scary, but in reality it’s the best place in England.

The teachers aren’t the spawn of Satan (well, some of them are) and you won’t get lost unless you don’t ask other people where something is. Just don’t join any house apart from School House and you’ll be just fine.

The lessons are demanding but fun. Make sure you do every subject so you have a real feel for what you want to do for GCSE and A’ Level. Take a shower every night. Clean your teeth, especially if you eat the same amount of junk food as some of my peers. Clean your desk, change your bedding and go to sleep as early as you can, so you can wake up bright and early.

Do all your homework two days early so you don’t get detention. Organize. Use Teams to the best of your advantage and check your emails ten times a second to make sure you don’t miss any events.

Respect your elders, especially the other years, and make as many good friends as possible. Connections are key at King’s.

Be kind to your matron since she will be the one looking after you when you are ill. Do not do anything that will upset her.

Most importantly, if you feel like what you are doing is wrong, don’t do it.

From LM

The 2022 Shells give advice to prep school pupils who are coming to King’s.

I know you must be really worried about coming to King’s so here are some ideas that, I hope, will calm you nerves. A thing you don’t need to break out about is buying stationery. I remember the anxiety and faff before coming to King’s about having the right equipment, only to realise that they have their own school shop in the social centre (a great place to hang out with friends and meet new people), selling everything from folders to rubbers.

Another thing to note before you come to King’s is reading – which I know you will love – but rather than just focusing on fun easyreaders, try a few classic novels (I promise, this will help). Not only do they make you smarter, but once you get started, they can also be super-enjoyable! If I had to give you a few recommendations, I’d say: Mrs. Dalloway, Jane Eyre, Animal Farm, 1984, Brave New World, All Quiet on the Western Front (which I am not sure is a classic but is great all the same), The Great Gatsby and Dracula (a difficult read but give it a go anyway).

This may sound obvious, but it is still important: don’t forget what you learnt before King’s. The summer holiday is a long time, and it is easy to forget things, but before you come to King’s just flick through your old books (if you haven’t destroyed them first) and refresh your memory.

As for some social points: remember to make friends early on, with people in your year, house, classes and especially your dorm (if you are a boarder). Remember you will be spending much of your five years with these people and it is advisable to make a good impression and loyal friendships early on, but don’t focus all of your effort into one person, because if they betray you, leave the school or are ill then there will be no one to turn to because everyone will have already joined other friendship groups. Also, be open-minded. King’s will be a great change, and you need to be prepared for anything thrown at you.

A few more things. Have a notebook to write down reminders. This will help them stick in your mind. Read everything assigned and do everything you are told but don’t forget to relax and enjoy yourself. Finally, it may be useful to join as many clubs and activities as you can. Not only are they fun but they will be useful later on while you develop your interests, and they will also impress your teachers and maybe even your (distant) future university.

Have fun. What is the worst that can happen?

Many thanks, BB

I know that you may be experiencing many different emotions in anticipation of the beginning of your time at King’s. I have been a Shell for little more than a month, but already there are many things I wish I had known before coming here.

First, try not to worry too much. Everyone says this, but it was only when I arrived that I realised it was true; I hate to use such a clichéd metaphor, but everyone is in the same boat. Everyone coming into Shell is guaranteed to be feeling nervous; it is likely that they are worrying about some of the same things you are. This especially applies to boarders if they are nervous about leaving home for the first time. Everyone gets homesick in one way or another, and you’ll probably get over it quite quickly.

One of the biggest things I was worried about is common to many people when beginning a new school: would I make friends? I wish someone had told me that this was not even worth worrying about. As long as you are amiable, kind, and polite, you are practically guaranteed to find someone amongst the approximately one hundred and fifty people in your year who you get along with. If you are boarding, you will automatically become close with the people in your dorm and house. There is always going to be someone you do not particularly like, but very few people at King’s are unashamedly mean. Even if you are worried about this, there are many people you can talk to. Shells have more free time than any other year at King’s, so use this time for trying new things, and seizing every opportunity. You could discover something that you really enjoy. Take advantage of all that’s offered, especially extra-curricular activities.

The older years at King’s practise several slightly unusual traditions, mostly dedicated to making fun of the Shells, but this is all done in good spirit. My advice is just to go along with it – make sure you respect the older years even if you disagree with some of them. They are, however, mostly more than willing to help you with anything.

At some point in the first few weeks of Shell, you will get lost. Because the school is spread out over such a huge campus, it is difficult at first to get your bearings, and it is inevitable that you will be late to some lessons because of this. There will always be people around to direct you.

If you are a boarder, make sure to bring lots of sweets and chocolate; don’t try and be that healthy person who brings mixed nuts and rice cakes if you don’t actually like them. You won’t end up eating them, and instead will have to stick out the first week without sweets before you can go into town and get supplies. Also, make sure you don’t buy long tracksuit bottoms because they’re really annoying and they just trail along the ground (this happened to me).

Try to enjoy it! Or at least get through the first few weeks. These are very busy, so half term arrives very quickly. Of course, none of this advice can truly prepare you for beginning as a Shell at King’s, but hopefully it will ease some of your worries, and reassure you that everyone has felt the same way.

Good luck! HF

Dear New Shell (and the fluttering butterflies in your stomach),

You’ve done it. You’ve made the ultimate decision to join King’s next year. You may be experiencing mixed emotions at this moment. Excitement may be prickling at your fingertips while worry tugs at your heart. It is completely natural to feel this way. This is a huge leap to a future you can’t foresee. Who wouldn’t you be nervous?

I came from Hong Kong, a small, bustling city packed with lights and noise. It had been my home for as long as I could remember. I had never expected to ever say goodbye to it, let alone take such a journey at the age of thirteen to go to school in the UK. Sitting in the plane, I looked down upon the glittering city of Hong Kong. By leaving it, I was also leaving behind everything I knew and loved: friends and family; restaurants I had regularly visited; the local library; everything that had watched me take my first breath of air offered by the sweet world.

There were moments when I wondered what the point of it all was. Why did I abandon the place I loved most, only to be faced with the unknown? Why did I stand there, left with a suitcase of memories, when I could have turned and walked back to familiarity and warmth? Why? Everyone’s been there – the time when you must take risks. I took that risk. My path forwards in life would never have been trodden as sure-footed as it is today, if I had stayed in that tiny city of unfulfilled dreams.

When I first came to King’s, I knew nobody and had no idea where to go. I was worried about making friends, for fear of being judged, excluded, and ignored. After my first few days of school, I realized that I had worried all for nothing. No one will judge you in any way at King’s. In only a matter of time, I was chatting with people of different cultures, nationalities, genders, and interests. We had fun together. Friends are everywhere, just waiting to be found. I was surprised at how friendly and welcoming everyone was to new pupils like me. It’s a nice feeling to be able to exchange smiles with someone passing by, or to receive random compliments that make your day. It’s a feeling of togetherness, clustered in the dining hall, and day and boarding houses. King’s will become like a second home to you in no time.

Don’t worry about not knowing where your next lesson is, or the route back to the main campus – everyone was once new and has experienced the same things that you’re going to. I remember being a little confused about some of the locations of my classes. Whenever I got lost, I would find anyone nearby –older pupils, teachers, members of staff – and ask them for directions. I did feel awkward and embarrassed; it was my third week of school, and I was still getting lost every now and then. If you ever find yourself having these thoughts, just remember that others will understand. No one judges anyone here at King’s. Take your time to remember where everything is. Take notes of it in your timetables and diaries. As well as locations, remind yourself of assignments given to you, and try to use most of the time given at the end of the day to do your prep. As daunting as it may be, the workload is manageable once you get the hang of it.

I am really thrilled that you’ll soon be joining us, and I hope you’re looking forward to it. Do your best, and good luck.

Dear New Shell,

I have been at King’s for a month now, so I thought I would write to encourage you about the coming academic year. If you are like me, you will be forcing the thought of being at a new school next year out of your mind. The truth is, to have some apprehension is natural but let me help you to clear your mind.

If you take any advice on board from this letter, you must take this: buy comfortable shoes and wear them in before coming to King’s. Otherwise, you will get blisters and you will not be able to walk, and that makes things a lot harder. Do yourself a favour and, before the first few days, when you will have tours and be running to and from the right and wrong classrooms, wear your shoes around the house so they become softer. Please.

As a young, new student, with no public exams that loom at the end of the year, it is vital that you keep an open mind. King’s offers an overwhelming myriad of opportunities and, whilst you can, it is astounding the variety of what you can take part in. Whether this is debating or dancing, give it a go. There is nothing to lose from going to an audition for a play or starting a new sport. Take advantage of everything you can, because you will never be at a place like this again.

New people are different. New people are interesting. New people are exciting. New people are not terrifying. Fear of the unknown can be hard to rationalise because, well, you just do not know what you will have to deal with. But, having an open mind, again, is key when you come to your new school. Make an effort with new people and do not prejudge them or their opinions of you. Push yourself to talk to someone different and to make connections all over your year. Just having one introductory conversation with someone can break the ice, and having a friendly face around school will make it easier to feel included.

Sometimes it is easy to forget that everyone wants to help you; no one is ‘out to get you’ and trying to make your life difficult. Ask if you need help with anything: getting lost, prep, lesson timings or music lessons. Everyone at King’s is happy to help and there is no shame in not knowing. But do not worry: you will figure things out much more quickly than you expect.

Now you have some helpful pointers for when you come to King’s, the transition should be smoother. Overall, remember to have an open mind about people and opportunities, and do not worry about not knowing. King’s is an amazing school, so focus on the positive aspects when you join because there are so many.

Best wishes, FB

I don’t want to claim how amazing the school is and how it’s a truly unique experience because honestly, when I was your age, if I read something like that I would immediately think that the student had a gun pointed to their head and was forced to write only generic nice things about the school.

Of course, I am not saying the school isn’t any of those things since, even though at the time of writing I am only half a term into the school, I have changed enormously as a person and have developed new skills, like being organised. But the greatest piece of advice I can give is that, although you may be at the top of your present school and you have all the power over the younger years, don’t let that influence you, because you will be joining a school with hundreds of other pupils and, trust me, you do not want to be the over-confident, insensitive person who talks back to older years. Ultimately what I’m getting at is, be confident but humble. You can be outgoing and make conversation with the older years, but you must remember the boundaries.

Homesickness is a huge problem in boarding school, and though I might not suffer from it, some of my greatest friends, unfortunately, miss their families, their beds, even their siblings. Although I don’t have any cure for this, and you just need to get used to it, I do have to say you have a multitude of people to talk to, whether it be Matron or just someone in your dorm. Personally, I find it very difficult to open up about problems in my life but one aspect of King’s I can truly appreciate is the availability of help from anyone.

The first thing that struck me about King’s is its genuinely interesting teachers. I was even somehow struck by a desire to learn FRENCH VOCAB! Now, of course, all the teachers at King’s are incredible, but the personality of some has truly hit me, making them my favourite teachers. The first not only finds fault with all my essays but can entertain the whole class for a total of three lessons while talking about the first 24 words of a long book, which really makes sure we don’t miss a single detail. In the lessons of the second I love the random tangents we pursue, starting from a 6a quotation like ‘I tell you I feel no emotions at all when I’m reading this’, but also discussing the insane patriarchy of ancient society. The third puts up with my constant lateness to lessons, and constantly forgetting my books.

My first month at King’s has been nothing but charming and enchanting. It is probably the easiest school to fit into because, unlike other schools I know, King’s truly embraces every talent no matter how wild it is. Ultimately what I love so much is the diversity of people. All my friends are so wildly different from me we have nothing in common but just being in the same environment, and this is enough to create the greatest bond. In the end the friends you make here will be your friends forever.

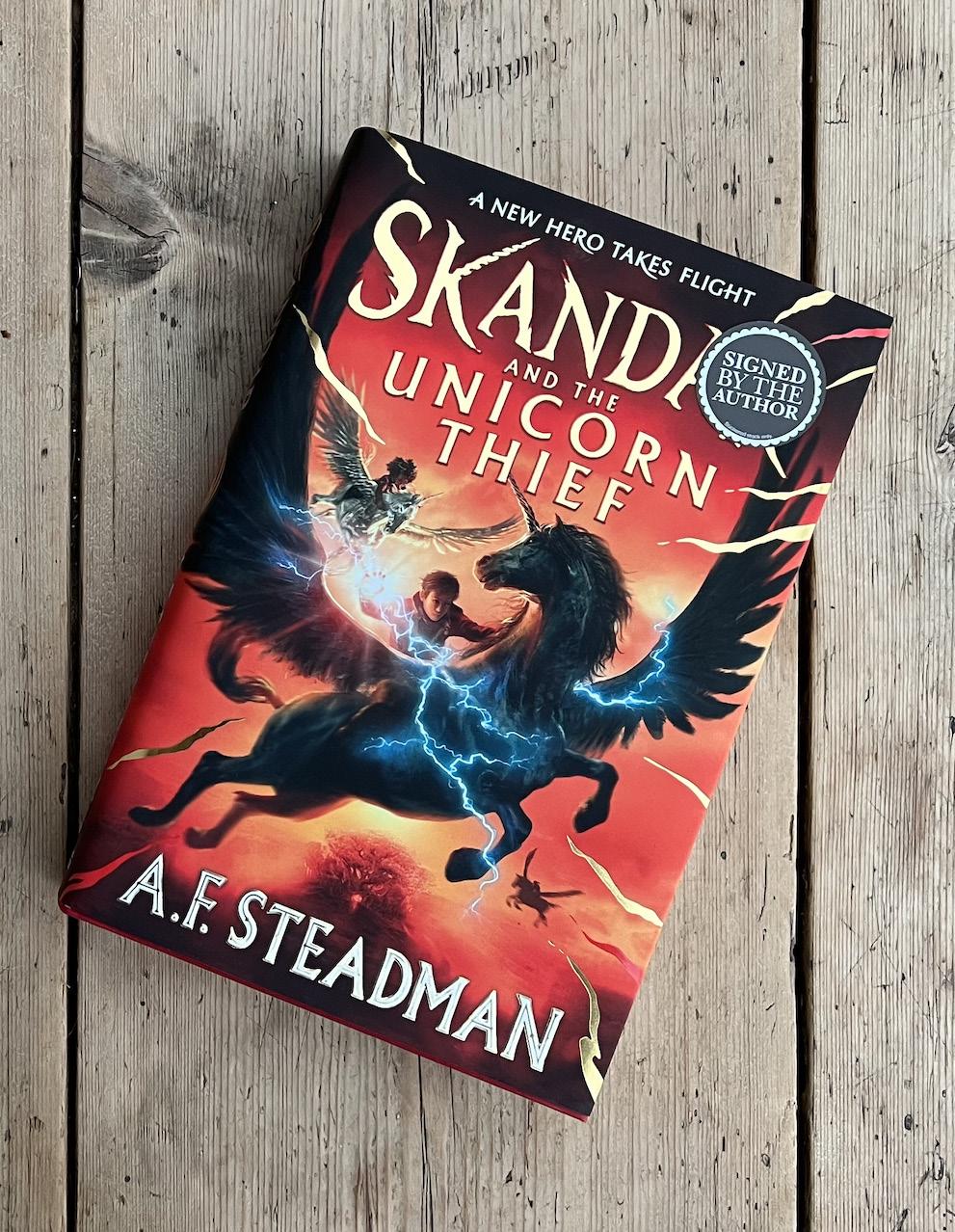

P B-EAre you a writer with novel ambitions? Here is some precious expert advice from A. F. Steadman OKS, author of the Skandar series.

Dear Writers,

As you embark on the tumultuous and rewarding journey of writing a novel of your own, I want to reassure you that every author I know – myself included – finds it challenging. There is a common misconception that writing a book should always be fun and easy, that if you’re not enjoying every second of it – or brimming with endless creativity, or effortlessly writing thousands of words a week – then you are not a true ‘writer’.

But what is a writer, really? For me, it is someone who puts pen to paper – or more likely fingers to keyboard nowadays – and perseveres because they want to tell a story. So much of writing a novel is an exercise in not giving up. When I write my first drafts, I have a daily wordcount. I work out how many words I need to write per day in order to get me to a whole book – in the case of the Skandar books, that’s around 80,000 words – in time to meet my deadline. Some days, I will write 1000 words in an hour without even looking away from my screen; on other days, it takes me five hours to write 100 words. I know that doesn’t sound very magical or romantic, but that’s what works for me.

Of course, that doesn’t mean I don’t run into problems on my way through the novel itself. And as you start your own books, I want to give you some advice that covers some obstacles writers face throughout the drafting process.

One of the most common worries when you start out on a novel is that your idea is not good enough for you to begin writing. A good piece of advice another author gave me is to try out the idea in a short story. Pick one aspect of the idea, or a character, or a single scene, and test it out. When you’ve written the short story, ask yourself whether you wanted to keep writing. Did it feel like there was more to be explored? If the answer to those questions is yes, then your worries about the idea are probably unfounded.

On the other hand, if you feel like the idea needs more development, then there’s plenty of ways to find inspiration. Listen to music – perhaps make a playlist to help you develop the world of the story or a particular character. Watch films or television series that cover similar ground to the idea you are thinking about. And of course, read books. Many writers struggle to write when they’re not reading, and I think that makes a lot of sense. It can be fiction, poetry, non-fiction, plays – anything. This will all help fill up your creative well and get your imagination flowing.

Once you’re happy with your idea and ready to start writing, your next challenge will raise its scary head: the blank page. This is the moment when you are staring at the white paper or computer screen and there is nothing on it. Not one word. You might type a sentence and then delete it immediately. It

‘What is a writer, really? For me, it is someone who puts pen to paper – or more likely fingers to keyboard nowadays – and perseveres because they want to tell a story.’

feels impossible that you will ever fill one page up, let alone three hundred. If you are encountering this problem, you are not alone. I have found that one way to overcome it is to plan out your novel. I’ll be honest and tell you I didn’t really plan my first book, Skandar and the Unicorn Thief. But as the series has gone on, I have made increasingly detailed chapter plans. Outlines can be as vague or as fleshed out as you like – some of mine are one line for a whole chapter; others are bullet points for almost every scene. Plans give you direction when you feel unsure of what is going to come next. They help you see the shape of the whole novel. But they are not for everyone or every book. An alternative way of combatting the blank page problem is to write out of order. I know some authors who write the end of the book first and

notebooks,

computer files

one third

then work their way up to it; I know others who write a collection of different scenes from different parts of the story in separate word documents and then splice them all together. Do what works for you.

At just over one third of the way through the novel, you are going to panic. I can almost guarantee you this. My theory is that this is the last point when you can turn back and start again. There are many words on the page already, and many more to go, and this is the stage you will ask yourself – is it worth it? Is it worth writing this story to the end? My best advice here is to try to keep going. Sometimes I wonder how many outstanding novels there are out there – in notebooks, in computer files – that are only one third

‘Sometimes I wonder how many outstanding novels there are out there – in

in

– that are only

written. Don’t let yours be one of those.’

‘This is the stage you will ask yourself – is it worth it? Is it worth writing this story to the end?’

written. Don’t let yours be one of those. Keep writing, even if you only manage one hundred words a day in your lunch break. Don’t stop. Don’t look back. Don’t delete.

When you get to the end you are going to think it’s a pile of rubbish. Everybody does. It’s not – but this is how you’ll feel. I think it has something to do with the fact you cannot read all of your book at once, you cannot see what you’ve written, and when you write that final sentence, the anxieties set in and make you forget all the good work you’ve done. Take a deep breath. Don’t read it straight away. Take a couple of weeks off from the whole thing, maybe even three if you have time. I promise you that when you come back to the novel you’ll impress yourself, you’ll surprise yourself – and you might even love what you’ve written.

One last thing to remember is that when you’re writing a first draft there really aren’t any rules. You just need to end up with a whole book –nobody needs to see how you got there. The books that you read in your lessons, or you buy from a bookshop, or find in a library, went through this whole process (and more!) before ending up on a shelf. Most writers wouldn’t want you to see their first draft, so don’t compare yourself to their finished work. Write the story you want to write, and I promise it will be worth it.

Wishing you the very best of luck on your novel-writing journey.

Yours sincerely, A. F. Steadman (2005-2010, MR)

‘Write the story you want to write, and I promise it will be worth it.’

A. F. Steadman grew up in the Kent countryside, getting lost in fantasy worlds and scribbling stories in notebooks. Before focusing on writing, she worked in Law, until she realized that there wasn’t nearly enough magic involved. She is the author of the New York Times bestselling Skandar series.

Ateacher of mine once quoted Krishnamurti, who said, ‘It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a sick society.’ This claim remained at the back of my mind for the next ten years, but it was only when I became a mother that I really understood the truth it tells.

No facet of Western society is sicker than the way we raise our children. We have become far detached from the biological and physiological needs both of children and mothers, and this detachment has become so ingrained in our culture that nobody questions it any more.

My generation has abysmal mental health. We abuse drugs and alcohol at an ever-increasing rate and our attention spans are shrinking decade by decade, but we fall into the same parenting patterns and make the same mistakes our parents made. Against those who do ask questions, we defend our decisions by saying, ‘Well, my parents did (x-y-z) and I turned out fine.’ To me, questioning whether I really was fine is a process I felt I owed my children.

In the UK, despite being a firstworld country with free healthcare, we have the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world. It is normal, even despite all our knowledge of attachment theory, to leave our newborn babies to cry in a room alone to ‘teach them independence’. The separation of mother and baby begins in utero. Formula companies sponsor maternity units. Dummies and bottles are given in welcome packs. We are told to buy formula ‘just in case’. Women are encouraged to breastfeed initially but as soon as the child is six months old, they are told they need to stop, that it’s somehow wrong or perverse, despite the World Health Organisation recommending feeding to ‘age two and beyond’ and the global average age of weaning from the breast being four and a half years.

Our health professionals receive only two hours of breastfeeding training, despite UNICEF estimating that even a moderate increase in breastfeeding rates could save the NHS a minimum of £40 million a year in protection against disease, not considering that the chances of breast, ovarian and uterine cancer in the mother decrease with breastfeeding duration. But in a culture where we tell parents ‘Fed is best’ to save both their feelings and the effort of providing adequate support, our rates are not going to improve. Fed is the bare minimum, so why can we not strive for better?

We are afraid of offending people, afraid to break generational patterns, but we might have to admit our parents could have done better if we are to encourage something that clearly has not only health and financial but also psychological benefits. This is not to say formula is not a worthy substitute in circumstances where breastfeeding genuinely isn’t available, but it should be offered on prescription, for free, thus removing the competitive advertising that is so capable of damaging the confidence and conviction within the breastfeeding relationship.

If feeding is the most contentious aspect of parenthood, then sleep is a close second. We are told we must put our children on a separate sleep surface, preferably in their own room, to protect them from suffocation and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). But in many other cultures there is no term for bedsharing or cosleeping; it’s just called ‘sleeping’. In Japan, where SIDS rates are the lowest in the world, it is the norm for children and parents to sleep on the same surface until the child decides otherwise, usually around ten years old.

In the UK, however, we go further than just putting young babies in cots in separate rooms. After nine months of being lulled to sleep in the safe, warm

Briony Cobb OKS (2009-13,

, who is training to become a doula, explains the right way to nurture a child.

‘In the UK, despite being a first-world country with free healthcare, we have the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world.’

environment of the mother’s uterus, babies don’t like being put in their own room, so they cry. But instead of responding to our crying children, our culture tells us to leave them to cry because they are manipulating us, despite not having developed the part of the brain responsible for manipulation until the age of three. It doesn’t consider why babies wake up – to keep themselves alive, regulate their own breathing through their parents (the reason we are designed to sleep close) and protect themselves from SIDS, which used to be called ‘cot death’ for a reason. The sleep-training lobby is now a multi-million-pound industry. It is also completely unregulated, which means that anyone can call themselves a ‘sleep coach’ and extort hundreds of pounds from exhausted parents by telling them they must go against the instinct that kept our species alive for hundreds of millennia and let babies scream until their systems go into shutdown and they stop crying to conserve energy.

Parents who leave their children to cry out will defend themselves by claiming there’s no evidence it’s dangerous, but the reason there is no direct evidence is because no ethics committee will pass a study that allows babies to ‘cry it out’ on the grounds that this could irrevocably harm attachment. Dr. James McKenna, a world expert in safe infant sleep, has a clear view: ‘Euro-American care practices and our infants’ ability to accommodate these practices suggest that we are pushing infant and maternal adaptability too far, with deleterious consequences for short-term survival and long-term health.’

When a mother breastfeeds and bedshares with her child, nobody makes any money, and the government takes no taxes. The culture needs to push back and change, but bad practice is so ingrained, and new parents are so vulnerable, exhausted and loaded with new hormones, that without policy change it’s unlikely this will happen. Policy change rarely happens when there’s no economic benefit.

‘‘Anyone can call themselves a ‘sleep coach’ and extort hundreds of pounds from exhausted parents.’’

The way we raise our children in the West is based on a cultural narrative fulfilling the needs not of our children but of patriarchal, white supremacist colonial capitalism or, as trauma therapist Kelly McDaniel says in her book, Mother Hunger, the ‘misogynistic and patriarchal life forces that disempower women’.

Given the state of the Western world these days I wouldn’t trust them with my dirty laundry, let alone the mental and physical well-being of my child. I trust instincts that have kept our species alive for a quarter of a million years. They seem to work.

‘Our culture tells us to leave them to cry because they are manipulating us, despite not having developed the part of the brain responsible for manipulation.’

Images: Briony Cobb - @bri_and_alf

Images: Briony Cobb - @bri_and_alf

Like the work of the great Greek poet, Pindar, the life of Peter Pinder OKS (1966-69, GL) celebrates the fruitful ups and downs of life and the stubborn genius of the mind’s eye. For more than 50 years now, Peter has lived on his creative wits and self-taught craftsmanship, and this is his tale.

Ihave fond memories of King’s. It was a refreshing change from my prep school, which was more like a Dickens boot camp. The freedom to buy chocolate was one of my first reliefs. And being allowed to bicycle anywhere we wanted.

On the academic side I was hopeless. I still have my report cards from 1966-69. I managed to be bottom in 80% of subjects, and was continuously on Satis, so I had to report to the Headmaster, Canon Newell, all the time. We got to know each other quite well.

I only realized later in life that there was a word for me. It wasn’t ‘thick’; it was ‘dyslexic’. I couldn’t read properly, amongst other things. I remember having to read out loud when it was my turn during evening prayers. The anxiety would build up days beforehand. And when the time came for me to read ‘The road to Damascus’, I started ‘The road to Domestos’. The roars of laughter continued while I stumbled through the rest.

What I did enjoy most at King’s was the carpentry shop, The Caxton Society and the art classes. But by the time O’ Levels came I only passed three, so I was doomed to repeat the Fifth Form. I called my father and told him I wanted to leave King’s and do something else. He was only too happy since he felt he was wasting his money on me. Asked what I planned to do, I had no idea, but told him Engineering.

‘‘When the time came for me to read ‘The road to Damascus’, I started ‘The road to Domestos’. The roars of laughter continued while I stumbled through the rest.’’

I then applied as an apprentice at Dennis Brothers in Guildford, who made fire engines, garbage trucks and other specialized vehicles. They first sent me to a government school that trained you on machines, and workshop processes, while you made your own tools. While receiving a salary from Dennis Brothers I had finally found something rewarding that I was good at. After a year I had to go to the factory and spend a few days in each department, then do six months on the chassis, installing the hydraulic brakes. After two months of this repetitive work, I quit. My mother was furious. I was 17 years old.

The one subject I wasn’t too bad at was Divinity, under Mr. Gollop. He always liked to pick on me in class. And since our class started just after recess, a lot of us were still eating snacks. If he caught you, he’d confiscate the food and eat it himself. So, one day I went to the Joke Shop, just outside the Mint Yard Gate, and bought some very spicy joke jellybeans. I pretend to eat one. He confiscates them. And eats one. Glaring, his face reddens, and he improvises a quick quiz, throwing a jellybean for each right answer. That didn’t go down too well.

So, with £200, a passport and a sleeping bag, I planned to visit my father in Switzerland, where he worked. While I was hitchhiking, it started raining, and when a truck stopped to pick me up, the driver asked me where I was going, and I told him Australia. He said he wasn’t going that far. But in my mind I was. And 13 months later, having passed through many exotic countries, with many stories to tell, I arrived in Darwin, the backdoor to Australia. I had no money left, nor any shoes, just a sarong and a Balinese T-shirt. Within an hour I got myself a job washing cars. After a few days I could feed myself and afford some shorts and flip-flops to blend in with the local mob. I also adjusted my public school accent to the Aussie twang, so I could get a job digging ditches in 100 degrees of heat.

Leaving Darwin, I hitchhiked around Australia, picking up odd jobs as I went. I ended up with a reasonable salary working in a gold, copper, and bismuth mine doing the assay. The mine was in the middle of nowhere, and I spent nine months saving up money. In the small hut they provided for accommodation, someone had left a Philippine Airline poster featuring a very attractive airhostess.

Knowing nothing about the Philippines, I arrived in 1972. And fell in love with the place. I met lots of very nice people and took a course in TV production as an excuse to stay longer and do something. But when Martial Law was declared, all TV and Media were closed down, so I returned to Darwin and got a job in the YMCA where they sent me 200 miles into the bush to start a YMCA with the Aboriginal tribes. I was my own boss. Since the YMCA had been sponsored by the government, they gave me an open shopping list of what I wanted: pick-up truck, a

small dingy with an outboard motor, film projectors, band equipment, trampolines, roller skates, and all the gymnastic equipment (since I used to be a gymnast) and all the art materials I could think of, including leather tools and jewelry-making stuff. And with more than 100 aboriginal children to do things with, I first learned how to do things, and then taught the children. We did batik, silk-screening, pottery, sculpture, painting and so on. The one thing I got a passion for was leather tooling. But the kids were a little impatient so I made them a gig they could use to make a belt for themselves in 30 minutes.

I would also take small groups out to far-away beaches where we would camp for a few days. They would go hunting and fishing the way their fathers had taught them, and we’d sleep in the sand around a fire. For two years I was having fun, and making more fun. For a Christmas break, and to report back to my bosses, I flew to Darwin, but on Christmas Eve 1974 Darwin was devastated by Cyclone Tracy and I had to resign my job in Maningrida.

I headed back to the Phillipines in 1975. And since then I have never left. I settled in Baguio, a town four hours north of Manila, 1500 metres up in the mountains. Not too hot, not too cold. It was established by the Americans at the beginning of the last century, a tribal area unconquered by the Spanish, where the Igorot tribes live. From them I first learned woodcarving, while I continued my leather tooling skills making all sorts of things with local designs inspired by the Igorot people. I put up a shop, and was commissioned by the Hyatt Hotel, who were building a hotel here, to do a tavern in tooled and painted leather. Soon after that, one of my bag designs got a big hit on the international

‘‘My latest work, which now hangs over one of the dining tables in the restaurant, is a diorama called ‘One Late Afternoon at Leonardo’s’, which is a whole story in itself. ’’

fashion market, and so I set up a small factory, and was able to buy land and build a house. I had three children already. I put up a shop in the Hyatt Hotel, making all sorts of things in leather, wood, fibreglass and combinations of them all, until 1990, when a 7.9 earthquake devastated Baguio, including the Hyatt Hotel.

By that time my Disco bags were already out of fashion, so I supplied the big department stores in Manila with all sorts of other things. It was quite tiresome having to go there every month. In 2008 I was thinking of something unique to sell in Baguio. And since Filipinos love trophies, and have a display corner in almost every household, I started carving small Igorot figures, doing their tribal dances and rituals, and made them into trophies. With a small collection, I made a flyer and gave them to schools, government offices, golf clubs, local festivals and various companies. They were an instant hit for the local market that usually got rather tacky shop-bought, mass-produced trophies. My range expanded fast as the market demanded custom designs, until 2020, when the pandemic hit. Lockdowns and all the events needing trophies stopped. So, with some of my workers, I built a bamboo house with bamboo from my son’s bamboo plantation. It gave me time to make things for the interior, ideas I’d had for a long time, but never found time for. After about a year building it, some wandering blogger posted it on the internet, and thus we got inundated with the curious. My wife Ella

thought of making it into a restaurant, aptly named Pinderella’s Kitchen. It now has many short videos on You Tube.

In 2022 my trophy business resumed fullspeed, with trained staff doing most of the work, which now leaves me time to have fun with whatever my dyslexic mind dreams up. My latest work, which now hangs over one of the dining tables in the restaurant, is a diorama called ‘One Late Afternoon at Leonardo’s’, which is a whole story in itself. The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party in the foreground, with da Vinci behind, painting himself in the mirror, while on the other side is Michelangelo, Leonardo’s former boyfriend, repairing the statue of his new boyfriend, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, which he called David. Out on the balcony at the back is Jesus and the Disciples having cocktails before supper.

Over the years I have made thousands of things. Some were hits; some were not. I even made a car out of a junked VW 1600. Copying a Hummer design made in fibreglass, half a Hummer and half a Bug, I aptly named it Bugger. Some of the other things I have made can be found on Google.

‘In 2022 my trophy business resumed fullspeed, with trained staff doing most of the work, which now leaves me time to have fun with whatever my dyslexic mind dreams up.’Two Aboriginal boys on Peter’s Belt-o-matic. The Baguio City Hall. A trophy depicting an Igorot dance. Bugger.

Isuppose the question is, how does someone who leaves grammar school in 1981 with a basic set of O’ and A’ levels, and who doesn’t go to university (well, actually, I was aiming at Portsmouth Polytechnic at one point), end up as Capital Projects Director at King’s, looking after, at this precise moment in time, the Mint Yard Science Development Project? A clue is in the title: by grafting!

My working career now spans over forty-one years, with only one week of voluntary ‘redundancy’ (between jobs) and encompassing only three employers, albeit one of them twice – King’s. It has been built almost entirely on graft plus basic ability, an accumulation of professional qualifications post-school, the acquisition of work-specific knowledge and, of course, some luck along the way.

My first piece of luck was sitting an aptitude test at an insurance company HQ in Gloucester when applying, with pressure from my father, who worked in the insurance industry, for an A’-Level trainee scheme. It turned out I had seen the aptitude test before in the form of a Christmas newspaper

quiz section only a couple of months back, so I was well placed to answer all of the questions!

I passed the aptitude test and started work in September 1981. I didn’t immediately warm to the professional exams that I was supposed to take, and ended up taking nine years to complete what others did in three, but I followed that up by motivating myself to undertake an additional qualification relating to my role as a risk control and property surveyor. That role had come about through hard work and determination to get out of the office and onto the road, which I managed at the age of 22, when at that stage the youngest surveyor in the company was 30. Hard work in the office, hard work on the road, covering thousands of miles and carrying out far more surveys than was expected, eventually led me to the role of Assistant Chief Surveyor at the age of 28. I had managed to impress enough people with my work ethic that I was entrusted with this position, ahead of those with more years of experience in the tank.