‘La République’

The French Embassy: A new direction to its soft power

Coco Xing’s Thesis Portfolio

Tutor: Laszlo Csutoras

Project G: Foreign Affairs

Introduction

page 4-5

Section 1: Traditional Role of The Embassy

page 6-11

Section 2: Embassy Mission Statement: A New Approach

page 12-13

Section 3: The reflection of the civil society

page 14-19

Section 4: Correlations between Indonesian and France

page 20-21

Section 5: The experiment of the new approach to embassy design

page 22-33

Conclusion

page 34-35

Bibiliography

page 36-45

Appendix

page 46-47

With the rapid development of society and the pattern of the world, the capability of military power is no longer suitable as a strength strategy for the current situation. France uses culture as its soft power to strengthen its influence to raise its global competitiveness.1 Diplomacy has shifted from unilateral expansion and plunder to win-win cooperation between developed and developing countries, seeking a delicate balance in mutual advancement. In the context of the embassy as a particular institutional building that symbolises the power and majesty of the nation in another country, and which is most of the time a completely inviolable and private domain that citizens are not permitted to enter freely, it is clear that the traditional embassy building in the past can be transformed into a space where public and private spheres can co-exist harmoniously in a way that is more accessible to the citizens of the nation and locals, and eventually to the welfare of the residents of the local community, thus becoming a theme that can be investigated.

As a traditional power, France has historically and culturally influenced the world. The German philosopher Jurgen Habermas defined the salon space, where the French aristocracy and the commoners interacted at the time, as an essential representation of the public sphere.2 Salon culture gave rise to the emergence of a civil society, which was further liberated in terms of cultural and ideological freedom. Is it possible to reverse the strategic significance of the Embassy from a more national to a more communal level?

Image 1. ‘Soft-Power-Pillars’.

1 Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, ‘Roadmap for France’s Soft Power’, France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, accessed 18 August 2024, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/theministry-and-its-network/the-work-of-the-ministry-for-europe-and-foreign-affairs/roadmap-for-france-ssoft-power/.

2 Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1992).

The Past

The Embassy was initially developed in Italy during the Renaissance, and embassies and resident ambassadorial officials in European countries subsequently followed it. Under Louis XIV’s reign, his diplomatic strategies combined with his political ambition were brutal and bloody, as well as military and wars. In contrast to such radical and inhumane tactics, and parallel to this, his substantial sponsorship of the Palace of Versailles led to the flourishing of French culture and the arts and the recognition of France as the future cultural hub of Europe.

France and Indonesia

Before the contemporary diplomatic relations between France and Indonesia were established in 1951,3 France was connected to Indonesia through the Dutch East India Company. During the Napoleonic Wars, France briefly ruled Indonesia after taking control of Dutch territories.4 In the meantime, Dutch Governor Herman built a grand palace in the French Empire style, known as Het Groote Huis.5 Shifting the timeline from history to present-day French diplomatic approaches and ties, with a particular focus on relations with Indonesia, cultural exchanges are the top priority in current relations between the two countries, followed by economic and military procurement relations.6 Also, not only the historical evolution, such as the Indonesian national awakening, which the French Revolution enlightened but also the continuity of the civil law system from France due to the influence of Dutch colonisation in terms of the law. Moreover, the political philosophy of the Republic of Indonesia is partly influenced by the model of the French Republic.7

Current State

In recent years, France has realised that the world is hyper-competitive and that the boundaries between soft power and traditional manifestations of authority have vanished. Rethinking the meaning of cultural diplomacy and soft power has become essential.8 Thus, France’s continued investment in educational programmes abroad and es-

3 The Jakarta Post, ‘France Celebrates Bastille Day in Iconic Style - Fri, July 15, 2011’, The Jakarta Post, accessed 10 November 2024, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/07/15/france-celebrates-bastilleday-iconic-style.html.

4 ‘Indonesia | History, Flag, Map, Capital, Language, Religion, & Facts | Britannica’, 9 November 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Indonesia.

5 P. A. Heuken, Historical Sites of Jakarta (Jakarta: Cipta Loka Caraka, 1982), 199-200

6 Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, ‘France and Indonesia’, France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, accessed 10 November 2024, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/indonesia/france-and-indonesia-65165/.

7 Timothy Lindsey, Indonesia: Law and Society, Fully rev. and exp. 2nd ed. (Annandale, N.S.W: Federation Press, 2008), 2

8 étrangères, ‘Roadmap for France’s Soft Power’.

tablishment of its own educational institutions locally constitute a new tool. In Jakarta, France has already built a French Institute to export French culture and values.9

The existing French Embassy in Indonesia was built in 2014 by Segond-Guyon Architects. The architecture consists of two modest five-storey blocks linked by a podium, one of which serves as the Embassy’s administrative space and the other as the French Institute. The building entrance has separate gates and is strictly secured and fenced. The two-storey podium occupies the entire buildable area. It includes publicly accessible spaces, such as the embassy’s control area and the main facilities of the French Institute, which feature an auditorium, library, and café.10 In this regard, the current French Embassy in Jakarta is designed to open a part of the space for cultural exchange to the public. Through the French Embassy officials, it can be noted that the French Institute offers French language learning programmes. However, the complexity of the security level of the Institute, which is adjacent to the Embassy’s premises, makes it seem like an inaccessible, high-security facility compared to a regular college.

Embassy as a typology

Throughout the history of the development of embassy architecture, from the mid-15th century when the Milanese used to send representatives to other Italian city-states in the most isolated areas of the existing palaces and private residences, and in line with the lifestyle of the aristocracy at the time to represent the monarch. Then, in the 19th century, the first embassies dedicated to Constantinople served as a stage for the great powers to fight against each other, and the buildings were designed as palaces on the hills to show the influence of the mighty empire. These stately buildings never cared about their surroundings but infused them with the neoclassicism of their country. Since then, embassy buildings have debated adopting local or national styles. As a result, embassy architecture also raised the fundamental political question of whether to retain one’s national style to impress the host with one’s strengths or show ‘goodwill’ to the host by imitating the local architecture.

Over the next sixty years, embassy architecture shifted from the neo-classicalism of the past to post-modernism as industrialised nations competed for power one after the other. Growing embassy entourages separated the ambassadors’ residences from the embassies, and some designers combined the two, using bridges as a linking tool. Emerging or less powerful countries have gained attention through sophisticated designs that convey soft power. For the great powers, embassy buildings were used during the Cold War as the best tool to represent a country’s image to the outside world, with each country trying to compete for attention using technological prowess and superior modernity to create an image of openness and forward-thinking. But this was dashed by repeated embassy bomb attacks, such as the 1983 bomb attack on the US Embassy in Beirut, which killed people. Eventually, the design strategy had to be changed, enhanced security measures were urgently implemented, and even the excellent location in the city centre was abandoned in favour of the suburbs to achieve tight fortifications. Therefore, many countries have followed suit since then. Hence, Wilkinson concludes that the design of

9 Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, ‘“Influence through Law” Strategy’, France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, accessed 18 August 2024, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/ the-ministry-and-its-network/diplomacy-roles/vital-diplomatic-work-conducted-from-france/article/influence-through-law-strategy.

10 ‘Embassy of France and French Institute in Jakarta / Segond-Guyon Architectes’, ArchDaily, 5 January 2016, https://www.archdaily.com/779863/embassy-of-france-and-french-institute-in-jakarta-segond-guyonarchitectes.

embassies is heavily influenced by the geopolitical climate, which has shifted towards creating symbols of protection and power.11

However, through on-the-ground observation at the embassy compound in Canberra, Australia, this does not seem to be the case. This may be due to the correlation between the relationship between the host country and the country the embassy represents and its international influence. The US embassy in Australia still has a reasonably tight defence mechanism. Still, because of the friendship between the US and Australia, the level of defence is visibly weakened compared to many countries that are at odds with the US. The French embassy in Canberra looks like the garden of a large suburban family with a two-storey building and no police reserve from the street. The Finnish Embassy in Canberra has the appearance of a neighbourhood library, with everything open and unfenced. This also shows that if the host country is on good terms with the embassy country, the design of the embassy will be more open and inclusive. The international status of the embassy country and its national strategic approach will also influence the level of defence of the embassy. 11 Tom Wilkinson, ‘Typology: Embassy’, The Architectural Review (blog), 9 December 2019, https:// www.architectural-review.com/essays/typology/typology-embassy.

Hence, through the preceding sections, it is possible to realise that the French Embassy has a solid potential to become a new typology of the embassy, which means turning from the severe traditional style to a more accessible and socially acceptable container of civil society. The design attempts to push the limits of the embassy’s security, providing maximum public space through the site’s original topographical changes and manageable circulations while maintaining the essential functions of the embassy properly at the same time. Therefore, the embassy’s role was shifted from an exclusive diplomatic space to a more open community-centric venue. On this basis, the embassy can be used as a culture hub, forming mutual cultural exchange with Indonesian local communities through collaborative initiatives instead of only exporting French culture. Also, the embassy could work as a platform for generating new open dialogue between nation the nation and the public through forums, exhibitions, performances, lectures, and other events, promoting values of inclusivity and shared growth.

The principal of civil society inevitably focuses on citizens. The evolution of the living environment of the citizens resulted in the emergence of public space, which became more of a multi-purpose venue related to political, environmental, and cultural affairs before the idea of space serving the public emerged. The definition of public space has also shifted with the evolution of society. In addition to the distinction between public and private spheres mentioned by Habermas, the political scientist Hannah Arendt showed in her research that social activities in Ancient Greece were also divided into those in the public realm and those in the private realm. They were both spaces that users could access, and both could create a harmonious and inclusive social environment. The difference between public and private was between the activities they hosted. Open spaces are considered to be huge, and neighbouring communities use these spaces for festivals, religious events, markets and occasional sports fields. Public space originates in Greece, where the marketplace was located at the centre of the city-state and was the outright public realm. The word Agora refers to the marketplace, which was also the site of social gatherings and political assemblies in the area. As such, it was the most symbolic of social, political and economic importance. It was a sacred place in those times, and its importance revolved around religion.12

Typologies of Public Spaces

UN-Habitat defines public spaces as places for various activities and must be multi-functional spaces for social interaction. They can be places where celebrations of a diverse culture can take place, provide basic amenities for community life, and allow for the movement of goods and people. Public spaces have many different spatial forms, including parks, streets, connected trails, recreational plazas, marketplaces, and spaces on roadsides and between buildings. Public spaces also have a vital role and position in society’s livelihood and human rights, facilitating economic exchanges and the dissemination of culture among diverse people.13

The Role of Public Spaces in France

Since the nobles invited literati, artists and experts to their salon events, the salon became the starting point of the Enlightenment.14 Society progressively shifts from noble to civil society, and the arts and literature are no longer exclusive to nobility. The Enlightenment was also one of the causes of the revolution.15 With the development

12 Riya Atray, ‘History of Public Open Spaces’, RTF | Rethinking The Future, 20 July 2022, https://www. re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a7347-history-of-public-open-spaces/.

13 UN-Habitat, ‘SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space.’ (United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi., 2018).

14 Mark Cartwright, ‘Parisian Salons & the Enlightenment’, World History Encyclopedia, accessed 25 September 2024, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2374/parisian-salons--the-enlightenment/.

15 Lindsay Bernhards, ‘The Center of Cultural Innovation: Parisian Salons’, accessed 11 November 2024,

of salon activities, the public’s voice was gradually heard in the cultivation of rational thinking brought by Enlightenment ideas, and the collision of expression and opinions in freedom eventually resulted in the French Revolution. The crash of the nobility finally transformed the noble society into a civil society, in which there were no more class discrepancies, and individuals were allowed to enjoy the entertainment that used to be exclusive to nobles.

Since then, the salon’s meaning has transformed from a gathering of literati dominated by the female aristocracy to a more universal public art exhibition.16 Public spaces on the street, such as the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots, became spaces where many scholars and literati met and exchanged new perspectives in the twentieth century.17

Different philosophers have defined civil society differently from Ancient Greece to contemporary Europe. Ultimately, the subject of civil society is the public itself, and the welfare and well-being of the public are the foremost priorities.

Interestingly, the discovery of public space in France is distinctive regarding using and observing public space during American Fourcher’s ten-day tour of Paris. Public space in France is usually highly preserved, whether it’s a park that has had a lot of labour and money invested in its maintenance, a closed and disused shop down the street that has been covered up by the landlord with an art installation, or a café that has been swept and rearranged during the day and at night to allow for the best possible interaction between the public and the space. Of course, in such an environment, there are expectations of people’s mannerisms, elegance, and reservedness, which are the opposite of the relaxed casualness and borderlessness of the Indonesians. For this reason, marketplaces in France are often organised by the state and government rather than private endeavours.18

Paris has the most cinemas worldwide per capita, and the cinema was born in France for entertainment, cultural exchange, and communication. The famous Cannes Film Festival, in addition to the screening of films in the Palais des Festivals et des Congrès, which is not open to the public, in 2001, the Cannes Film Institute and the Cannes City Council cooperated in providing free cinema services to local citizens and festival attendees every night during the festival, which is conducted outdoors and is exclusively a temporary event for the general public.19

The museum is the most popular public space for cultural expression in modern cities, and George Bataille has commented that the origin of the contemporary museum is closely related to the development of the guillotine. The establishment of the Louvre Museum, the most famous museum in France, is directly related to the French Revolution. Before this, the Louvre was the seat of the French monarchs, but it was, in turn, a container for artwork for a long time, as monarchs all over the world displayed their wealth and authority with their collections during that era. Furthermore, museums were closely associated with politics and expressions of power. But before the Revolution, the state https://www.edgeofyesterday.com/time-travelers/the-center-of-cultural-innovation-parisian-salons.

16 Regina De Con Cossio, ‘The Origins of the French Salon’, Sybaris Collection (blog), 22 August 2018, https://sybaris.com.mx/the-origins-of-the-french-salon/.

17 Annette Charlton, ‘Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots - Two Famous Paris Cafés | A French Collection’, accessed 12 November 2024, https://www.afrenchcollection.com/who-wins-parisian-rival-cafes/.

18 Mike Fourcher, ‘The French Way of Open Space’, Middling.Industries (blog), 23 July 2022, https:// middling.industries/2022/07/23/the-french-way-of-open-space/.

19 ‘Cinéma de la Plage’, in Wikipédia, 1 August 2024, https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cin%C3%A9ma_de_la_Plage&oldid=217278573#cite_note-4.

and the aristocracy usually controlled art production; the Academy carefully managed it, and visitors were restricted to the elite; the Louvre, as an exhibition space for works of art, was more like a fortress, irrelevant to the general public. Then came the Revolution, when all fine art was finally recognised as the public wealth of the people, not only as a declaration of wealth but also as a statement of civilisation, education and democracy, known as the Enlightenment.20

Case study for functioning and programming: Palais de Tokyo – Lacaton and Vassal

The Palais de Tokyo was designed as a venue for world expositions from the beginning, with two separate museums. The Palais de Tokyo, often discussed today, is on the west side of the building, which has hosted many different events. In addition to the traditional history of the museum, the later establishment of The Palais du cinéma, the Centre National de la Photographie, the Institut des Hautes Études en Arts Plastiques and the contemporary art centre all reflect the temporary and flexible character of the institutions and events that have been hosted in this venue. The Institut des Hautes Études en Arts Plastiques was an episodic educational institution, the Palais de l’Image was never formally used, and the Centre National de la Photographie was later relocated for the creation of the Musée d’Art Contemporain. Thus, the Palais de Tokyo, both preceding and after its transformation by Lacaton and Vassal, is characterised by the temporary aspect of events and exhibitions as well as institutions.21

Lacaton and Vassal extensively used what was already there in this renovation, retaining the great freedom of space rather than dividing it to achieve maximum spatial freedom and mobility, making it more open and welcoming. They felt that the place had to work like a town square. So, they referenced the notion of access, meeting place, and spatial freedom that the place Djemaa-el-Fnaa in Marrakech brings to the table. A ground without dividing lines, obstacles and limitations of street furniture, a completely open space, infinitely self-renewing and changing with the use and movement of people. In this refurbishment project, stairs and footbridges, only light interventions, have been used outside to improve accessibility and safety, weakening the monumental significance that the site brings, thus reflecting its temporary character.22

20 Elizabeth Rodini, ‘Museums and Politics: The Louvre, Paris (Article)’, Khan Academy, accessed 13 November 2024, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/approaches-to-art-history/tools-for-understanding-museums/museums-in-history/a/museums-politics-louvre.

21 ‘The Site & Its History - Palais de Tokyo’, accessed 14 November 2024, https://palaisdetokyo.com/en/ the-site-and-its-history/.

22 ‘Rehabilitation of the Palais De Tokyo’, Architectuul, accessed 14 November 2024, https://architectuul. com/architecture/rehabilitation-of-the-palais-de-tokyo.

Indonesia is formally a presidential republic, but it is the product of a delicate compromise between secularism and the ideology of the Islamic regime. The first of Indonesia’s five founding principles, ‘Pancasila,’ requires citizens to ‘believe in God Almighty’. Citizens must choose one of the six religions recognised by the government (Islam, Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism) and register, and atheists may be discriminated against.23

The history of Europe is difficult to summarise briefly in a few words in a very short paragraph, but the perceived shift towards a decline in the view of divinity ought to be apparent. From the medieval nightmare of being controlled by the Papacy, then the Renaissance, which put aside religious concepts and praised the ancient Greeks for their wisdom without being controlled by religion, but mainly identified with their notion of aesthetics rather than with their notion of the divinity, onwards to the Enlightenment, which favoured education in scientific theories and eventually to the present time, when all kinds of modernism are prevalent, French culture has seen the part of the divinity eliminated gradually.24 This contrasts sharply with the strong religious ethos of Indonesia.

According to Plato’s idea of a city and citizens, despite the justice and the ideal city, in his Republic, he described the good life as challenging consumer culture and the idea that satisfying desires defines the good life, which is a virtue, wisdom, and self-discipline that leads to a state of well-being and fulfilment, or eudaimonia.25 Additionally, looking at Politics by Aristotle stated that “man is by nature a political animal” in this book. Humans will self-identify as caring about society, the country, and the citizens around them. Therefore, the engagement of citizens in public affairs and social discourses is responsible for achieving a true republic.26 By consuming these two ancient Greek wisdoms, it is obvious that we should understand the primary desires that a city or society should have, which are to satisfy a human’s good well-being and create a supportive environment with engagement by providing humane care towards a commonwealth of goodness, in the term of Greek Agathos

23 Rémy Madinier, ‘Pancasila in Indonesia a “Religious Laicity” Under Attack?’, in Asia and the Secular, ed. Pascal Bourdeaux et al. (De Gruyter, 2022), 71–92, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110733068-005.

24 ‘Renaissance | Encyclopedia.Com’, accessed 15 November 2024, https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/language-linguistics-and-literary-terms/literature-general/renaissance.

25 Dorothea Frede and Mi-Kyoung Lee, ‘Plato’s Ethics: An Overview’, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Winter 2023 (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2023), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/plato-ethics/.

26 Cheryl E. Abbate, ‘“Higher” and “Lower” Political Animals: A Critical Analysis of Aristotle’s Account of the Political Animal’, Journal of Animal Ethics 6, no. 1 (2016): 54–66, https://doi.org/10.5406/janimalethics.6.1.0054.

Context analysis

Plans to relocate Indonesia’s capital were conceived as early as the 1950s. At the beginning of this century, plagued by severe traffic and environmental problems in the current capital, Jakarta, this idea started to gain traction with concerns. It was not until 2022 that the project was officially launched. On the island of Kalimantan, Nusantara is a pristine site, a blank paper to be painted by the government. The ruling leaders had grand ambitions to construct this deserted land into an environmentally friendly cosmopolitan city.

Not only because of these unsolvable and intractable realities, the idea of relocating the capital was used as a political tool. The first was to de-centralise Java and Jakarta and to ameliorate the imbalances of power, influence, and municipal infrastructure in areas marginalised after independence. As the capital city of a twentieth-century post-colonial state, it was tasked with telling its citizens and the world about its nationalist ideology. Post-colonial strategies of national construction have also resulted in the design of the capital city being dominated by monumental buildings and urban spaces that represent the national vision of the ruling regime. At the same time, civil society and ordinary people are often objectified and not treated as actual occupants.

Achmadi argues that the elaborately designed capital cities, such as Brasilia and Canberra, dominated by grand architecture and urban spaces, are devoid of civic character. They tend to symbolise state power and rarely reveal the real social dynamics of the country. She also suggests that the design of the capital should provide a diversity of public spaces that should not mask the informality of Indonesian urban life in favour of providing space for it. The new capital should facilitate the emergence of a more robust civil society in Indonesia and allow civil society to play a role in its democratic future. Hence, the new capital should not use the urban form solely to reflect the identity of the country as perceived by the elite but rather to serve and promote interaction between the various socio-economic classes of the urban population. 27

27 Amanda Achmadi, ‘After Jakarta: Imagining a New Capital’, Indonesia at Melbourne (blog), 25 June 2019, https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/after-jakarta-imagining-a-new-capital/.

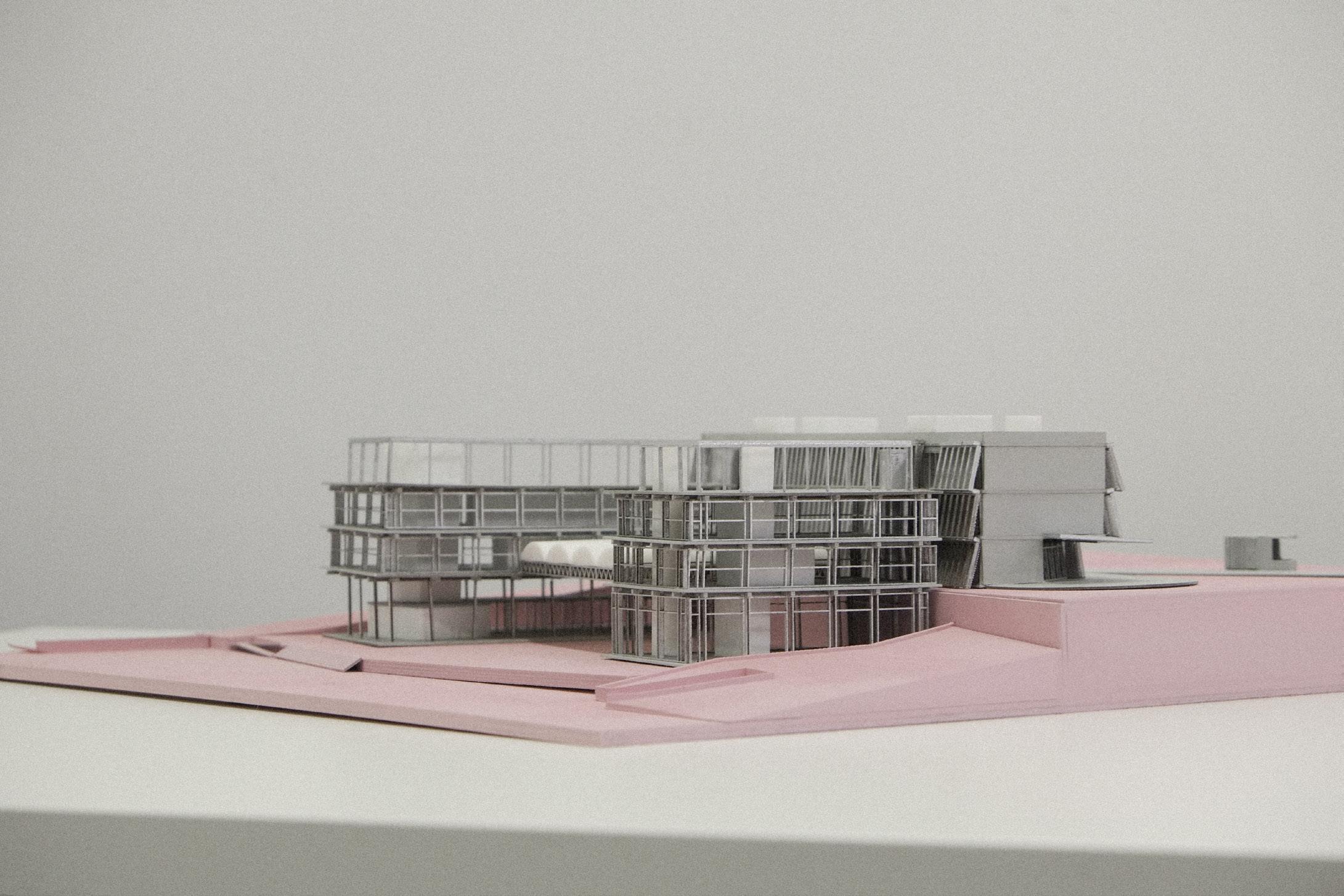

This new French Embassy design in Nusantara reflects the warm relationship between Indonesia and France, currently defined by robust economic, trade, and cultural exchanges grounded in peaceful dialogue. Most Indonesians hold a positive view of France, appreciating the cultural richness that has come to characterise French diplomacy today.28

Considering these friendly relationships, this embassy design departs from the more traditional, secure, and enclosed structure of the French embassy in Jakarta. While the existing embassy includes a French cultural centre, its enclosed setting limits public interaction, creating a barrier to the openness that contemporary diplomacy increasingly values. This design takes on the challenge of rethinking embassy architecture to balance secure private office and residential functions with unprecedented openness to the public, thereby creating a space where citizens can engage with and explore civic responsibilities in an open, inclusive environment.

The new embassy seeks to serve as a welcoming platform for citizens, allowing a degree of access that aligns with the embassy’s role as a bridge between nations. The design builds a space for diplomatic affairs and intercultural interaction, where everybody alike can experience shared dialogue through activities such as stand-up comedy, lectures, performances, art classes, language courses, film screenings, and book clubs. By inviting people to participate in these activities, the embassy’s public spaces become integral to the local community, eventually serving as a social condenser that forms gatherings and idea exchanges reminiscent of France’s salon culture. Historically, French salons were spaces where intellectuals and artists exchanged perspectives with nobles, often challenging established ideas and advancing social progress.

German philosopher Jürgen Habermas famously defined the salon as a core element of the public sphere. According to Habermas, the public sphere is the social realm where citizens can freely discuss public affairs and participate in politics independently of formal political power—a critical foundation for democracy.29 In simpler terms, it is a public space where citizens can express themselves without interference from the state, existing between governmental structures and society. As a reference to ideas mentioned in the previous section, Aristotle defined human beings as “political animals” with an innate inclination to engage in civic life and governance.30 Embassies, by their nature, embody a country’s presence and responsibility within another nation. However, they are often designed as formal, distant institutions, discouraging public engagement. Therefore, it will match the idea of Plato’s goodness in life and the city.

While the embassy symbolically resonates with these values, it does not need to express them through architectural features explicitly. Instead, it should function as a vessel that supports republican ideals. Through accessible, everyday activities as an anchor point that welcomes the public, the design moves beyond the embassy’s usual formalities, transforming it into a space devoid of hierarchical implications—a step towards a republic where it serves as a forum for managing shared public matters.

28 BBC, ‘2013 World Service Poll’, 10 October 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20151010192245/ http://www.globescan.com/images/images/pressreleases/bbc2013_country_ratings/2013_country_rating_ poll_bbc_globescan.pdf.

29 Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere.

30 Abbate, ‘“Higher” and “Lower” Political Animals’.

A balance between openness and inclusivity to security

To achieve this balance of openness and security, the design leverages the natural topography, which offers steep terrain as a natural barrier to separate secure office and residential spaces from public zones. This spatial separation is enhanced by strategically controlled circulations and schedules that harmonise public and private use. Different users have dedicated pathways to prevent interference. The ambassador’s entrance and the main office entry are situated on opposite sides of the office building, ensuring privacy through distinct circulation cores while maintaining connectivity.

French architect Dominique Perrault used metal mesh as the façade of the cycling and swimming pool complexes in the competition organised by Berlin to bid for the Olympic Games. By drawing on this practice, to utilised the bullet-proof properties of metal mesh in the design of the embassy, adding a layer of misty vision and strong protection to the embassy office building, which is entirely made up of floor-to-ceiling glass windows, thus further enhancing the openness of the embassy without neglecting adequate security.

In addition, the design of the stadium also makes the public space conscious of the urban fabric, transforming the surrounding site into a more democratic and user-friendly, and eventually anti-authoritarian, building.31 Although the stadium is an entirely public building compared to an embassy, which should maximise the public aspect, it is still worthwhile to learn from this point of view.

31 Arquitectura Viva, ‘Olympic Velodrome and Swimming Pool, Berlin - Dominique Perrault Architecture’, Arquitectura Viva, accessed 16 November 2024, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/velodromo-y-piscina-olimpicos-2.

The use of spatial typology

The consulate area is accessible from the underground parking directly to a public plaza, library, and café. Visitors entering the consular offices are filtered through a reception area before accessing the main service floors. The topmost office levels, linked by a private bridge and elevator to the embassy’s main workspace, offer additional privacy and dedicated rooftop gardens for staff. In essence, the public area of the embassy is a fully enclosed space, beginning from the auditorium on the ground floor, ascending through a central dining area, and reaching a multifunctional hall at the top. These spaces serve as amenities during the week and transform into public weekend areas.

Not only will the temporary programmes be running under the Shed, but there are also some possible temporary activities and functions that we could recall regarding the temporalities that the Palais of Tokyo had. For instance, the restaurant on the first floor draws inspiration from the Malaysian embassy in London, which serves traditional Malaysian dishes to the public on weekends, creating a cultural exchange.32 Similarly, the multifunctional second floor could offer French language classes, continuing the educational role of the French Institute in Jakarta.33

The ambassador’s residence, a penthouse situated on the second floor of the embassy’s office building, offers a seamless transition between private and public areas. The left side hosts the household’s private quarters, the central section houses the ambassador’s residence, and the right side features a reception area that opens onto a rooftop garden shared with the embassy’s public building, ideal for hosting private dinners and receptions as a salon as a parlour.

32 ‘Malaysia Hall Canteen - London’, accessed 15 November 2024, https://malaysiahall.has.restaurant/.

33 ‘IFI Jakarta’, Institut français Indonésie (blog), 4 November 2024, https://www.ifi-id.com/jakarta/.

In the context of Nusantara’s development as a new capital, this embassy serves as a model for inclusive civic architecture. It recognises the importance of public spaces in creating a sense of community and belonging. As a platform for cross-cultural dialogue, it provides opportunities for Indonesians and the French to engage in meaningful exchanges, deepening their understanding of one another’s histories, values, and aspirations via temporary events.

A completely new city deserves an experimental challenge. There is no way for architecture not to act as an ideological container. If this is necessary, architecture must serve the majority better than it serves the very minority. The design reflects the evolving role of embassies in the modern world and tests the possibilities of balancing the public sphere and the private sphere. By merging security, openness, and functionality, it redefines the embassy not as a distant symbol of state power but as a dynamic venue for cultural diplomacy and public engagement. This shift represents a forward-thinking vision for the role of architecture in diplomacy, paving the way for a more inclusive and interconnected future.

The design of this embassy theoretically enables a shift from subjectification to objectification of civil society towards the institutions of other governments, undermining the pursuit of cultural symbolism and the embodiment of state authority that has characterised the design of embassies in the past. It challenges the traditional aspirations of embassy architecture and transforms the embassy from a status of weak connection with citizens to a status suitable for civil society’s reverie on the architecture of an institution that represents the public.

In our relatively peaceful generation, this design could be seen as a visionary experiment grounded in the aspirations of republican ideals. It may be a dream or a hopeful trial for a future where embassies truly serve as platforms for civic engagement, open to the citizens they represent.

• Abbate, Cheryl E. 2016. ‘“Higher” and “Lower” Political Animals: A Critical Analysis of Aristotle’s Account of the Political Animal’. Journal of Animal Ethics 6 (1): 54–66. https://doi.org/10.5406/janimalethics.6.1.0054

• ‘Agora’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://camo.githubusercontent.com/2620356938523c09b197cf305044c574a0c3cd22113b1986acc9295f6c2d02d7/68747470733a2f2f692e70696e696d672e636f6d2f6f726967696e616c732f35372f31632f34322f35373163343264313437663834666638393 161326336313763343237636136352e6a7067

• Amanda Achmadi. 2019. ‘After Jakarta: Imagining a New Capital’. Indonesia at Melbourne (blog). 25 June 2019. https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/after-jakarta-imagining-a-new-capital/.

• Anonymous. 2022. ‘Why Indonesia Matters’. The Economist 445 (9322): 16.

• Atray, Riya. 2022. ‘History of Public Open Spaces’. RTF | Rethinking The Future. 20 July 2022. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a7347-history-of-public-open-spaces/.

• ‘Australian Accused of Ramming into US Embassy Gate’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https:// lh3.googleusercontent.com/AqCEXOpw4XJEyOhSGu-8QgPmcN0ayQW7Ax_OyOmXCwTPE-cjvJU-eRAdoCRy3z9ntTxNAKlA6XY-4kkerKm7nMa3c7CrQnVtdw=s512

• Avermaete, Tom. 2018. ‘The Socius of Architecture: Spatialising the Social and Socialising the Spatial’. The Journal of Architecture 23 (4): 537–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2018.1479353

• BBC. 2015. ‘2013 World Service Poll’. 10 October 2015. https://web.archive.org/ web/20151010192245/http://www.globescan.com/images/images/pressreleases/bbc2013_country_ ratings/2013_country_rating_poll_bbc_globescan.pdf.

• Cartwright, Mark. n.d. ‘Parisian Salons & the Enlightenment’. World History Encyclopedia. Accessed 25 September 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2374/parisian-salons--the-enlightenment/

• Charlton, Annette. n.d. ‘Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots - Two Famous Paris Cafés | A French Collection’. Accessed 12 November 2024. https://www.afrenchcollection.com/who-wins-parisian-rival-cafes/

• ‘Cinéma de la Plage’. 2024. In Wikipédia https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cin%C3%A9ma_ de_la_Plage&oldid=217278573#cite_note-4.

• Cossio, Regina De Con. 2018. ‘The Origins of the French Salon’. Sybaris Collection (blog). 22 August 2018. https://sybaris.com.mx/the-origins-of-the-french-salon/

• Crow, Thomas E. 1985. Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris. New Haven: Yale University Press.

• Cupers, Kenny. 2014. ‘The Social Project’. Places Journal, April. https://doi.org/10.22269/140402.

• Elizabeth Rodini. n.d. ‘Museums and Politics: The Louvre, Paris (Article)’. Khan Academy. Accessed 13 November 2024. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/approaches-to-art-history/tools-for-understanding-museums/museums-in-history/a/museums-politics-louvre.

• ‘Embassy of France and French Institute in Jakarta / Segond-Guyon Architectes’. 2016. ArchDaily. 5 January 2016. https://www.archdaily.com/779863/embassy-of-france-and-french-institute-in-jakarta-segond-guyon-architectes

• étrangères, Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires. n.d.-a. ‘France and Indonesia’. France DiplomacyMinistry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Accessed 10 November 2024. https://www.diplomatie.gouv. fr/en/country-files/indonesia/france-and-indonesia-65165/

• ———. n.d.-b. ‘“Influence through Law” Strategy’. France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Accessed 18 August 2024. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/the-ministry-and-its-network/ diplomacy-roles/vital-diplomatic-work-conducted-from-france/article/influence-through-law-strategy.

• ———. n.d.-c. ‘Roadmap for France’s Soft Power’. France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Accessed 18 August 2024. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/the-ministry-and-its-network/ the-work-of-the-ministry-for-europe-and-foreign-affairs/roadmap-for-france-s-soft-power/.

• Frede, Dorothea, and Mi-Kyoung Lee. 2023. ‘Plato’s Ethics: An Overview’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Winter 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/plato-ethics/

• ‘French Ambassador Returns to Australia After Submarine Dispute’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bbf8e9c0b77bd1b70356eee/1634046280405-H6XFUFYLIZZKKSEJI9FJ/7893512762_3e15af5070_b.jpg?format=2500w

• ‘Gedung-Aa-Maramis’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://images.bisnis.com/ posts/2022/03/22/1513597/gedung-aa-maramis.jpg.

• Habermas, Jürgen. 1992. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

• Heuken, P. A. 1982. Historical Sites of Jakarta. Jakarta: Cipta Loka Caraka.

• Hill, Hal. 2000. ‘Indonesia: The Strange and Sudden Death of a Tiger Economy’. Oxford Development

Studies 28 (2): 117–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688310.

• ‘IFI Jakarta’. 2024. Institut français Indonésie (blog). 4 November 2024. https://www.ifi-id.com/jakarta/

• ‘Indonesia | History, Flag, Map, Capital, Language, Religion, & Facts | Britannica’. 2024. 9 November 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Indonesia.

• ‘Indonesia Is Poised for a Boom—Politics Permitting: Thousand-Island Progressing’. 2022. The Economist (Online), November. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2736376665/abstract/B1E509320C7048C7PQ/1.

• Lemonnier, Anocet. n.d. ‘Salon of Madame Geoffrin’. World History Encyclopedia. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/image/18461/salon-of-madame-geoffrin/

• Lindsay Bernhards. n.d. ‘The Center of Cultural Innovation: Parisian Salons’. Accessed 11 November 2024. https://www.edgeofyesterday.com/time-travelers/the-center-of-cultural-innovation-parisian-salons.

• Lindsey, Timothy. 2008. Indonesia: Law and Society. Fully rev. and exp. 2nd ed. Annandale, N.S.W: Federation Press.

• ‘Louvre Museum’. n.d. Expedia.Com.Au. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://www.expedia.com.au/ Louvre-Museum-Paris-City-Center.d502223.Attraction.

• Madinier, Rémy. 2022. ‘Pancasila in Indonesia a “Religious Laicity” Under Attack?’ In Asia and the Secular, edited by Pascal Bourdeaux, Eddy Dufourmont, André Laliberté, and Rémy Madinier, 71–92. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110733068-005.

• ‘Malaysia Hall Canteen - London’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://malaysiahall.has.restaurant/

• Mike Fourcher. 2022. ‘The French Way of Open Space’. Middling.Industries (blog). 23 July 2022. https://middling.industries/2022/07/23/the-french-way-of-open-space/.

• Molly. 2021. ‘A Brief History of Salons’. The Salon Host (blog). 5 June 2021. https://thesalonhost.com/ brief-history-of-salons/

• Post, The Jakarta. n.d.-a. ‘France Celebrates Bastille Day in Iconic Style - Fri, July 15, 2011’. The Jakarta Post. Accessed 10 November 2024. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/07/15/francecelebrates-bastille-day-iconic-style.html.

• ———. n.d.-b. ‘July 14 Spirit Enlivens Relations between France and Indonesia - Tue, July 14, 2020’. The Jakarta Post. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2020/07/13/ july-14-spirit-enlivens-relations-between-france-and-indonesia.html.

• ‘Rehabilitation of the Palais De Tokyo’. n.d. Architectuul. Accessed 14 November 2024. https://architectuul.com/architecture/rehabilitation-of-the-palais-de-tokyo

• ‘Renaissance’. 2024. In Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Renaissance&oldid=1256048611.

• ‘Renaissance | Encyclopedia.Com’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/ literature-and-arts/language-linguistics-and-literary-terms/literature-general/renaissance

• ‘Salon | Etymology of Salon by Etymonline’. n.d. Accessed 8 August 2024. https://www.etymonline. com/word/salon.

• ‘Soft-Power-Pillars’. n.d. Accessed 15 November 2024. https://brandfinance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Soft-Power-pillars-1.jpg

• Tchoukaleyska, Roza. 2018. ‘Public Places and Empty Spaces: Dislocation, Urban Renewal and the Death of a French Plaza’. Urban Geography 39 (6): 944–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1 405872

• ‘The Site & Its History - Palais de Tokyo’. n.d. Accessed 14 November 2024. https://palaisdetokyo. com/en/the-site-and-its-history/

• Twilley, Stephen. 2020. ‘The Enduring City: Jakarta, Indonesia’. Public Books (blog). 6 May 2020. https://www.publicbooks.org/the-enduring-city-jakarta-indonesia/

• UN-Habitat. 2018. ‘SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space.’ United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi.

• Vidler, Anthony. 2014. ‘Architecture and the Enlightenment’. In The Cambridge Companion to the French Enlightenment, edited by Daniel Brewer, 184–98. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781139108959.014

• Viva, Arquitectura. n.d.-a. ‘Olympic Velodrome and Swimming Pool, Berlin - Dominique Perrault Architecture’. Arquitectura Viva. Accessed 16 November 2024. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/velodromo-y-piscina-olimpicos-2

• ———. n.d.-b. ‘Palais de Tokyo, Paris - Lacaton & Vassal’. Arquitectura Viva. Accessed 25 September 2024. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/palais-de-tokyo-10.

• Wilkinson, Tom. 2019. ‘Typology: Embassy’. The Architectural Review (blog). 9 December 2019. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/typology/typology-embassy

• Williams, Tom. 2022. ‘View the Full Cannes 2022 Cinéma de La Plage Lineup Below’. British Cinematographer (blog). 18 May 2022. https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/view-the-full-cannes-2022-cinema-de-la-plage-lineup-below/.

‘La République’ by Coco Xing 2024

Tutor: Laszlo Csutoras

Project G: Foreign Affairs