COAmag

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Editorial EDITOR

Daniel Mahoney

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Rob Levin

EDITORIAL ADVICE

John Anderson

Dru Colbert

Darron Collins ’92

Jennifer Hughes

Caitlin Meredith

Suzanne Morse

Chris Petersen

EDITORIAL CONSULTANT

Jodi Baker

DESIGN

Corey Blake

Z Studio Design

Administration

PRESIDENT

Darron Collins ’92

PROVOST

Ken Hill

ASSOCIATE ACADEMIC DEANS

Jamie McKown

Bonnie Tai

DEAN OF ADMISSION

Heather Albert-Knopp ’99

DEAN OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

Shawn Keeley ’00

DEAN OF ADMINISTRATION

Bear Paul

DEAN OF STUDENT LIFE

Sarah Luke

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Rob Levin

Board of Trustees

TRUSTEE OFFICERS

Beth Gardiner, Chair

Marthann Samek, Vice Chair

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

DAN MAHONEY

Since I began thinking about the 50th anniversary issue of the magazine and how to honor the past while looking toward the future, I’ve had the image of the Roman deity Janus in my mind. Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. In sculptures, drawings, and coins, Janus is depicted as having two faces looking simultaneously to the past and future.

I was introduced to Janus by the art film distribution company Janus Films. Starting in the early 1950s, Janus brought an amazing array of international films to audiences in the US, including the work of Sergei Eisenstein, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, François Truffaut, and Yasujiro Ozu, among so many others.

The directors of films distributed by Janus extended time in ways most directors in the US did not. Movies in the US seemed to want to crush time into a ball, to make two hours feel like 20 minutes.

Our host told us El Comandante regularly gave long speeches venerating the Cuban Revolution. He loved taking his audiences back to 1959, but was unable to register the boredom on their faces in 2000. For Castro, the present and future were in a constant state of surrender to the revolutionary past.

Hank Schmelzer, Vice Chair

Ronald E. Beard, Secretary

Jay McNally ’84, Treasurer

TRUSTEE MEMBERS

Cynthia Baker

Timothy Bass

Michael Boland ’94

Joyce Cacho,

Alyne Cistone

Barclay Corbus

Sarah Currie-Halpern

Heather Richards Evans

Marie Griffith

Cookie Horner

Anniversaries are times we look to the past and the future. We look at where we were and where we are going. One purpose of an anniversary is to congratulate ourselves on making it this far. Huzzah, COA! Onward we go!

Nicholas Lapham

Casey Mallinckrodt

Anthony Mazlish

Chandreyee Mitra ’01

Nadia Rosenthal

Abby Rowe

Laura McGiffert Slover

Laura Z. Stone

Steve Sullens

Claudia Turnbull

LIFE TRUSTEES

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

John N. Kelly

William V.P. Newlin

When my spouse and I were in Cuba, we happened to catch a televised speech by Fidel Castro. I should say, we caught some of a speech by Castro, as the entire thing lasted four hours and we had a whole country to see.

As Darron points out, COA founding president Ed Kaelber said: Any college that is not constantly seeking new ways of doing things is only half alive. I don’t know if it’s the natural beauty of campus, my smart and funny colleagues, the bracing wind off of the Atlantic, or the amazing students, but being at COA, I’ve never felt more alive.

John Reeves

Henry D. Sharpe, Jr.

TRUSTEES EMERITI

David Hackett Fischer

William G. Foulke, Jr.

Amy Yeager Geier

George B.E. Hambleton

Elizabeth D. Hodder

Philip B. Kunhardt III ’77

Chantal Akerman’s film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, distributed by Janus Films, features one of the most amazing scenes I’ve ever seen. The lead character, Jeanne Dielman, mixes and shapes ground beef into a meatloaf in real time. I’ll just say that again, she mixes and shapes ground beef into a meatloaf in real time. The whole thing is glorious.

The film Jaws came out in 1975, the same year as Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. The amazing scene in Jaws where Quint, Brody, and Hooper sing after showing each other their scars, lasts as long as it takes Jeanne Dielman to shape a meatloaf.

There are wonderful pieces of writing in this issue of the magazine that deal with time and the challenges of being present: A conversation with Okwui Okpokwasili, College of the Ecstatic, and Today is not special. I hope you devour each of them.

Philip S.J. Moriarty

Phyllis Anina Moriarty

Cathy Ramsdell

Hamilton Robinson, Jr.

William N. Thorndike

John Wilmerding

EX OFFICIO

Darron Collins ’92

At College of the Atlantic, we envision a world where creativity, presentness, compassion, respect, and diversity of nature and human cultures are highly valued. A world where all people have the opportunity to construct meaningful lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of future generations.

COA Magazine is published annually for the College of the Atlantic community.

coa.edu

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger says, “If we can see the present clearly enough, we shall ask the right questions of the past.” I keep looking for a third face on Janus, one that signifies the present.

For a preteen a year is endless, but for an octogenarian 50 years passes in the blink of an eye. COA is moving into exciting territory: new faces, new buildings, new energy—don’t blink or you might miss it.

Beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings is a whole lot of territory for a single god to cover, but the Romans were nothing if not ambitious.

According to Eleanor Roosevelt, the coolest first lady in history, “Tomorrow is a mystery. Today is a gift. That’s why we call it ‘The Present.’”

If Janus were to have a third face—a face for the present—I’d want it to look like COA emeritus faculty in philosophy John Visvader. For many years John led weekly Tai Chi sessions at COA. On certain mornings, in the midst of a chaotic 10-week term, there would be an oasis of calm movement happening in the center of campus. As he led these sessions, John would repeat the phrase: make it delicious…make it delicious…make it delicious… Dan

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT

DARRON COLLINS ’92

Back out of all this now too much for us ... Here are your waters and your watering place. Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.

Robert Frost, DirectiveCollege of the Atlantic is many things: a geography—acreage delineated on maps; an assemblage of infrastructure—buildings and sheds and the metal, glass, and wood that give them form and function; a legal entity— an institution with the authority to grant degrees based on collectively established norms. Yet, as we look back at our 50-year history and project our thoughts into the future, I feel most satisfied describing COA as a collection of some of the most driven, creative, and caring people the world has known. We are the students, staff, faculty, trustees, alumnx, parents, philanthropists, and partners who have walked these acres, who have been sheltered and nourished by this architecture, and who have wrestled with, and built, and benefited from the idea of human ecology.

human ecologists who, across the past five decades, have worked to build a better world.

In the words of our founding president, Ed Kaelber:

Any college that is not constantly seeking new ways of doing things is only half alive. But the very fact that there has been the need to coin the phrase ”experimental college” is an indication that the structures and teaching methods of many colleges have become rigid and unresponsive to changing conditions in our society.

College of the Atlantic expects to be experimental in the best sense of the word. Above all, we will build into the structure of the college a mechanism that insists on continuing evaluation. Without selfcriticism, rigor becomes empty form and compassion becomes merely sentiment. Education, as we see it, is possible only as this institution changes to reflect new knowledge and new techniques aimed at meeting the changing needs of man [sic] and his environment.

Here at COA, we have done that selfcriticism and self-correction—and we continue to be experimental, even with 50 years of academics under our belts. Without jettisoning the kernels of brilliance and distinctiveness in our genetic code, our experimenting, evaluation, and self-criticism is carrying us through an institutional adolescence in many important ways.

2 About our cover

3 News

3 Love of philosophy spurs chair gift

4 Housing needs come to the fore

5 COA celebrates 50th academic year

6 New faces

12 Goldsworthy comes to COA

14 College of the Ecstatic

16 Student profile: Isidora Muñoz Segovia ’22

18 Just doing my part

22 COA’s community garden celebrates its 50th year

24 Alumnx profile: Ryan Higgins ’06

25 A farewell letter to the COA community

26 Home on the range

31 Donor profi le: Mary K. Eliot, Casey Mallinckrodt, and Walter Robinson

32 Student profile: Desmond Williams ’23

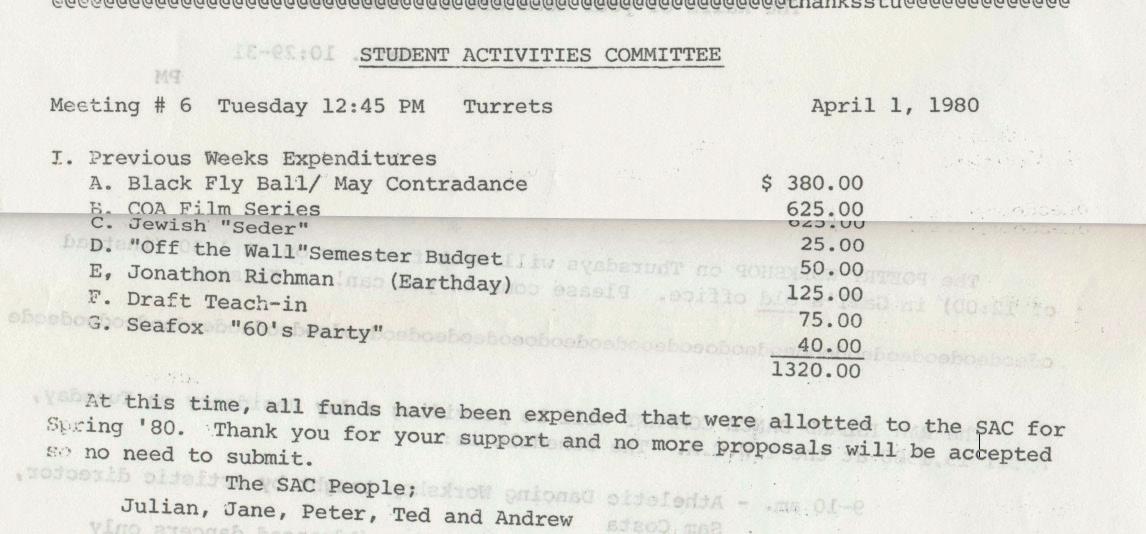

34 Off the Wall

36 Origins

Centerfold: To dwell in possibility

38 Islands in our lives

40 Looking for the weather inside

44 Bits & pieces

46 Alumnx profile: Jasmine Smith ’09

48 Why I give: Lisa Bjerke ’13, MPhil ’16

49 Alliances

50 Difficult conversations

51 Interns in the community

52 Creating lasting cross-cultural relationships

And there are thousands of us. In these pages we celebrate the stories and the work of some in the hopes of painting an impression of us all. That work is one of watercolor, not hyperrealism. As any human ecologist worth their mettle would do, we don’t only relish the past, but sift critically through our stories with a methodical kaizen geared toward a better next 50 years.

I often find myself imagining being at an All College Meeting in the 1970s, surrounded by the Kaelbers and Carpenters and Katonas, by the Pingrees, Johnsons, and Hazards, building an institution to reverse the failing health of the planet. We have come so far, on so many fronts, and for this we can point gratefully to the ideas and actions of so many COA

Today, our version of human ecology is profoundly connected to the real world. I find a most powerful hope in this connectivity because we have successfully resisted the all-too-plausible future where connection homogenizes to an educational leastcommon denominator. I find hope because our people—those who make us who we are—have made wildly creative, wonderful homes and lives in a multitude of places, all while embracing and deriving inspiration from the world some of us once turned our backs on. That connectivity is what has provided, and what will continue to provide, the speed and creative power of experimentation we need in these times. Frost’s Directive was a foundational text at COA when students arrived in 1972. It continues to be foundational to me to know that our watering place feeds, and is fed by, a much larger aquifer.

Enjoy reading this special 50th academic

54 Of islands and institutions

55 Transformative experiences

56 Alumnx notes

59 Community notes

63 Retirements

64 In memoriam

66 Making something from everything…

67 Alumnx books

70 Millard

71 Today is not special

year edition of COA Magazine with both a celebratory and critical eye on our past so that you—one of those foundational people I spoke of earlier—can continue to help strengthen our form and function.

Most importantly: thank you for being a part of this wonderful and wonderfully experimental college, Darron

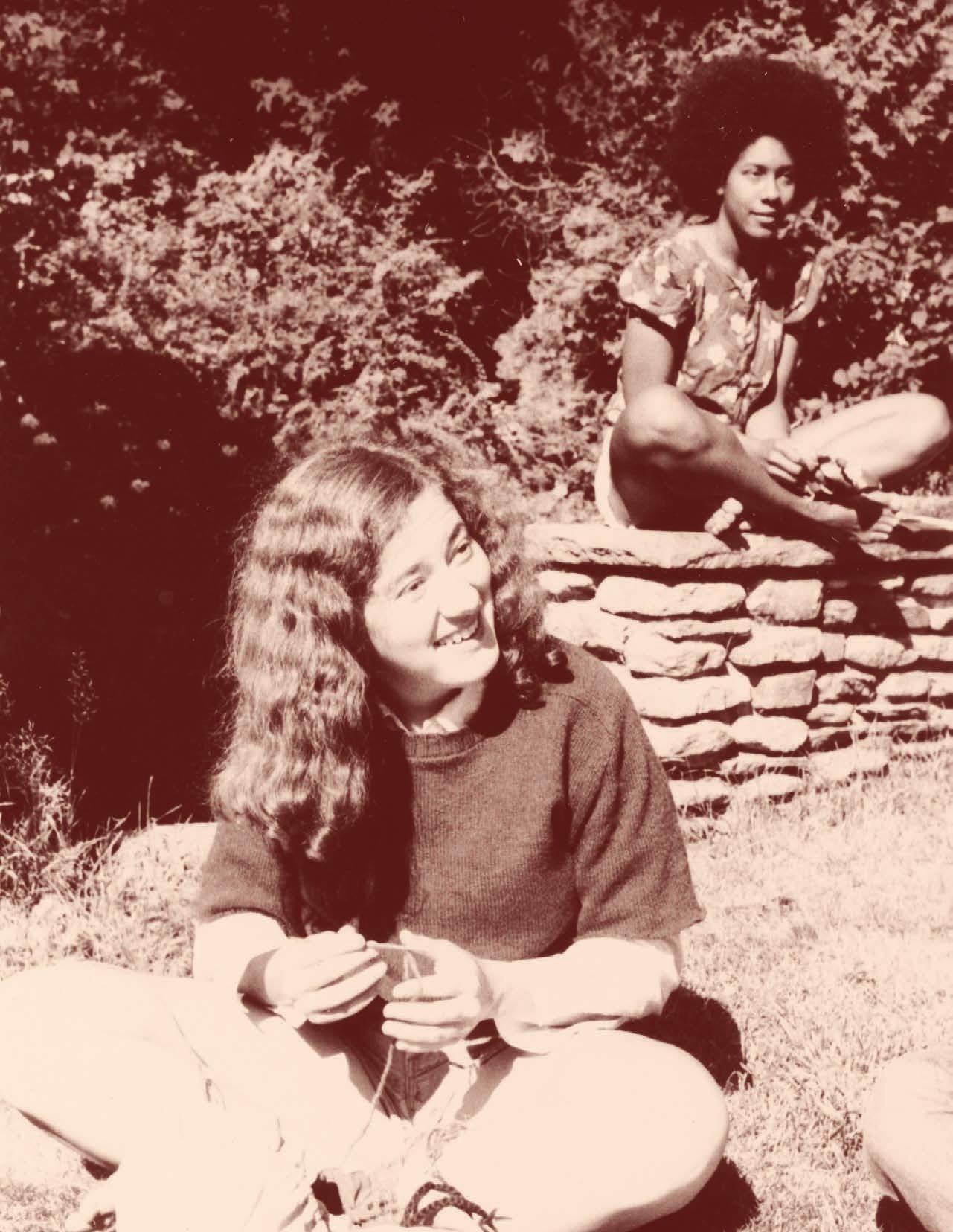

About our cover

By Rob LevinIn the summer of 1971, 13 students and three faculty members embarked on the College of the Atlantic experimental pilot program. Their challenge was to test and evaluate what would become COA’s interdisciplinary, place-based approach. Working collaboratively, those students and faculty joined several staff members and trustees in raising and answering questions about the future direction of the college. Among that intrepid bunch were Diane Pierce-Williams and Jill Tabbutt-Henry. Their engaged work and spirit of open exploration helped prove COA as a concept, which, one year later, in the fall of 1972, would lead to the college’s first academic class.

DIANE PIERCE-WILLIAMS

As a member of the first entering class at another experimental, interdisciplinary institution, participating in the pilot program for the soon-to-open College of the Atlantic was the perfect summer job for me.

Although there was no degree or certification in the offing, we took our courses seriously. Each of us worked toward a final project, researching and presenting our notions of what could happen on Bar Island. As I recall, Jill was creative enough to propose an aquaculture facility. My own idea was much less visionary: that it should be a nature preserve.

Like at other residential colleges, much of our joy and growth came during extracurricular moments. There were the usual frisbee games, meetings, and late night discussions. Other aspects were more particular to that time and place such as watching the comings and goings of the Bluenose ferry, standing firewatch at night, or exploring the abandoned mansion next door.

There is something else I carry besides treasured remembrances of an idyllic summer in Bar Harbor. COA provided a certain intellectual infrastructure. My vocational pursuits have included positions as varied law professor, community volunteer, and librarian. All those roles had to do with how people interact with their environments, thus I have remained a proponent of human ecology during the half-century since I was first introduced to the concept. I deeply appreciate that COA continues to offer that framework to others.

and now:

JILL TABBUTT-HENRY

That summer at COA, 1971, quite simply, changed my life. It made me realize that education—at its best—is dynamic, evolving, and focused on the needs of the learners—and the world itself. It made me think about not only what I wanted to learn, but how I wanted to learn it. I went off to my first semester at another college after that, but it paled in comparison. I would soon return to COA to be part of the admissions staff, selecting the first year of students—including myself!— and staying for two years.

Some years later, I got bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the fi eld of community health education. I was a family planning community educator, worked internationally as a curriculum developer and trainer in sexual and reproductive health counseling, and was a curriculum developer and trainer in long-term, homebased care.

I had learned at COA that I could find my path by holding education accountable to meeting my needs. I applied those same principles in all my curriculum development and training work—addressing the needs of the learners. I will always be grateful for the impact on my life of that summer program, with its smallbut-stellar staff, and the tiny college that grew from it. They taught me self-worth, resilience, creativity, and to always question both the purpose and the impact of my actions on the world. What incredible gifts! What an incredible education!

Then and now: Diane Pierce-Williams Then Jill Tabbutt-HenryLove of philosophy spurs chair gift

By Rob LevinACOLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC

ALUM who was one of the driving forces behind the technology that helped expose the biggest corporate securities fraud of the 21st century is behind the creation of a new academic chair in philosophy at College of the Atlantic.

Jay McNally ’84, whose data analytics software played a key role in uncovering important details of the notorious Enron scandal, said that endowing The McNally Family Chair in Human Ecology and Philosophy is one way of making sure that current and future COA students are exposed to many of the same ideas that influenced the early years of the college.

“Important elements of the COA curriculum, like transdisciplinarity, self-directedness, or experientiality, there are philosophical issues that are tied to that, and those issues have greatly influenced my life and career. I have felt unconstrained,” McNally said.

COA students as they navigate their selfdesigned academic paths, he said.

“Philosophy is one of the mirrors that helps let us know who we are. In a way it’s also a compass that tells us where we are going. It tells us what the nature of the world is, and in a certain way keeps us honest,” McNally said. “Understanding ethics and morality is a key way that we, as individuals or as cultures, can make determinations on why we do the things we do.”

Dr. Heather Lakey ’00, MPhil ’05 is the inaugural holder of the McNally Family Chair. As an undergraduate and graduate student at COA, through a second master’s degree at University of Oregon and the doctoral program at University of Maine, Lakey deeply understands the importance of philosophy to an interdisciplinary education.

said. “It is an honor to be appointed to this position and I am grateful to the McNally family for enshrining philosophy as a core part of COA’s curriculum.”

Studies in philosophy and ethics drove McNally’s success with Ibis Consulting, his pioneering electronic discovery firm that worked on the Enron case, he said, and his self-directed COA education continues to influence his interactions with the professional world.

“There are always ways to push the direction of an investigation rather than follow the evidence, but the idea of morality and ethics and the ability to look at yourself in the mirror and know that you were an honest and truthful broker is one of the reasons I became popular among influential people to handle these things,” he said.

“I was encouraged at COA to question and analyze and be responsible with my activities, but to explore the territory and make the connections that were important to me.”

Philosophy and ethics, McNally said, underpin science, business, and culture. This vital, interdisciplinary role makes this area of study especially important to

“Because human ecology studies the relationships between human beings and their natural, cultural, and constructed environments, it is imperative that we think carefully about these concepts and their complex interrelationships. What do we mean by human? What distinguishes a natural environment from a cultural or constructed one? Philosophy provides intellectual resources to productively engage these questions and to imagine new ways to theorize these relationships,” Lakey

“Conducting complex legal investigations required the ability to talk to a lot of people from very different perspectives, including law, technology, and business. At COA I learned how to learn, and I learned how to work with other people.”

The McNally Family Chair is established in honor of the graduation of McNally’s daughters, Rose Besen-McNally ’19 and Lily Besen-McNally ’20, from COA. Rose is currently a graduate student at University of Maine, and Lily is enrolled in a graduate program at Maine College of Art.

Jay McNally has served the college as a trustee since 2002. He previously helped create, endow, and instruct in COA’s sustainable business program, helped fund a chair position in the humanities, and founded the Russo Scholarship, in honor of his grandparents, Rose and Michael Russo.

“As a college that has very deep intellectual roots, it’s important to make sure that the education at COA never becomes superficial, that we continue to question everything, that we continue to examine the world in deep detail, and that we continue to look for connections in disparate areas,” he said.

“The McNally Family Chair is one of the things that will allow us to do that in perpetuity.”

Housing needs come to the fore

By Rob LevinASKY-HIGH, ultra-competitive housing market, lack of affordable housing, and diminishing rentals are issues being felt across the US, and the communities around COA that have been traditional sources of student housing are no exception. While students here have long grappled with a lengthening tourist “shoulder season” making some rentals unavailable at the beginning of the school year, the rise of Airbnb and pandemic purchasing of second homes has led to record-low amounts of available housing at all.

With this new reality in mind, college officials have adjusted development priorities, paused the multi-stage project on the north end of campus (the Davis Center for Human Ecology was the first of several planned developments), and set their sights on increasing student housing options. Utilizing more than $8 million raised in the recent Broad Reach Capital Campaign for student residences, the school has made offcampus purchases in Bar Harbor, partnered with a community revitalization group in Mount Desert, and set plans in motion for a new residence hall on campus within the past year.

“By greatly increasing capacity on campus and adding space in town and on the island, we’ll have gone a long way toward assuring a productive and beneficial living and learning environment for every COA student,” says COA president Darron Collins ‘92. “While the college has long favored the idea of having many of our students live off campus and support local landlords, the profound changes to the rental market have caused us to rework how

we approach housing, and led us to develop a program that better supports our students’ needs.”

Starting in earnest in the fall of 2021, OPAL architect Tim Lock and project manager John Gordon, who worked together with architect Susan Rodriguez on the recent Davis Center for Human Ecology, met with students, staff, trustees, and faculty to scope out the need for new housing. The result: a planned 12,000-square-foot residence hall with room for nearly 50 students, built to Passive House standards. The facility, slated to open in fall 2023, will include a fully outfitted, multi-stationed community kitchen, large common area with exposed mass-timber beams, and a covered outdoor gathering area. The building is proposed for the south end of campus, near the south parking lot and Blair/Tyson residences.

The College of the Atlantic Mount Desert Center, developed in partnership with community revitalization group Mount Desert 365, will bring space for 15 students, a faculty/staff apartment, and a year-round storefront to Main Street in Northeast Harbor beginning this summer. The project, made possible with gifts from Mitch and Emily Rales and Lalage and Steve Rales, was designed by Gordon, wearing his hat as an architect this time and working with project manager Millard Dority, COA’s founding director of buildings and grounds who retired this year (see page 70). Energy performance and low-carbon emissions are again at the forefront of the design.

In the fall of 2021, COA was presented with the opportunity to purchase the

“Summertime” apartments on Highbrook Road and a small block of houses on Norris Avenue and Glen Mary Drive, both in Bar Harbor. The nine properties, with room for nearly 40 students, had typically been rented to COA students during the academic year, so when they went on the market, Collins, dean of administration Bear Paul, and others knew they had to act. Those properties, now securely in COA’s hands, underwent major energy and efficiency upgrades with guidance from director of energy David Gibson (see page 8) during the winter.

Combined with the Birch Tree Lane apartments just to the north of campus that were acquired in 2019, the college now has rental space off campus for 80 students. When the new campus residence hall opens in 2023, COA will have capacity to house 290 students, or 83 percent of the 350-person student body.

“I cannot overstate my gratitude to the many people who helped make these changes possible,” Collins said. “I want to thank each and every one of them for helping COA students thrive.”

Development plans for the north end of campus—which include removing the old arts and sciences building and adding additional performance space to Gates Community Center, a welcome pavilion off the entrance drive, and a multi-use building near the center of campus—are still planned, even if timing is up in the air. Funding for these projects was included in the successful $55 million Broad Reach campaign.

COA celebrates 50th academic year

By Rob LevinRECORD ENROLLMENT, a new, 30,000-square-foot academic center, and a cadre of strong regional partners in attendance highlighted College of the Atlantic’s 50th convocation ceremony.

Scores gathered for the event in front of the new COA Davis Center for Human Ecology, an interdisciplinary, passive house facility with regionally sourced, mass timber construction, 350 solar panels, wood fiber insulation, and triple-insulated, bird-safe windows. Speakers included COA governance moderator Olivia Paruk ’24, architects Susan Rodriguez of Susan T Rodriguez | Architecture • Design and Tim Lock of OPAL, Craig Kesselheim ’76 of COA’s first incoming class, and COA President Darron Collins ’92.

The center includes a new teaching greenhouse, dedicated on Sept. 9 as the Congresswoman Chellie Pingree ’79 Greenhouse, with the Congresswoman on hand for the occasion.

“I’m so proud of my alma mater College of the Atlantic for remaining dedicated to ecology and innovation,” Pingree said.

“For 50 years, COA has put Maine on the national map for positive climate action. Their new, beautiful Davis Center for Human Ecology will nurture growth and green learning for generations to come.”

COA’s 50th academic year began with the largest applicant pool in the college’s history, 536 applications for approximately 100 spaces. Fall 2021 marked the college’s highest fall enrollment to date, with 373 students from 49 countries and 40 states. That number leveled out to around 350 fulltime-equivalent students over the course of the academic year, which is the school’s enrollment cap.

“The 50th class marks an impressive chapter in COA’s history,” said Paruk at the opening of the afternoon convocation ceremony. “This is a great time for introspection, where we can learn from our past, and continue to grow and enrich ourselves to help serve all current and future change makers without losing sight of the ideals we hold close to our hearts.”

The college has come a long way since its founding in 1969 and first enrollment in

1972, Kesselheim said in his alumnx address.

“As a prospective student, I came to a campus where there were no classes to visit, because the college hadn’t actually started yet. There were no students to mingle with or chat with or just get a vibe from. There were no faculty on campus, there was no cafeteria to sample, no dorms to peek in on,” Kesselheim said. “So, instead we talked to the founders of the college… who wanted this year-round institution to be part of Bar Harbor life, island life, and we talked about their dreams, and considered ourselves invited.”

The Davis Center for Human Ecology is COA’s first purpose-built academic building since the early 1990s. It was designed during a multi-year community process by Rodriguez in collaboration with OPAL, and built within COA’s rigorous discarded resources framework by Maine’s E.L. Shea Builders and Engineers.

“Our team has worked hard to design a building that could only be here. One that is derived from this unique intersection of the natural world and the study of human ecology,” Rodriguez said.

Palak Taneja, literature and writing

By Rob LevinCOLLEGE OF THE

ATLANTIC is pleased to welcome Palak Taneja as a new faculty member in literature and writing.

As a child, Taneja made her way to and from school in busy Jalandhar, India, once the site of one of the largest refugee camps in the world. An overly quiet student who liked best to blend into the background, Taneja was brilliant with her studies and loved to learn, but so shy that barely a teacher knew her name. That all began to change when she discovered the power of literature, and a series of excellent English teachers helped her discover that stories could serve as a medium through which to understand the world, and gain one’s voice in the process.

Later, studying English at the University of Delhi, a fascinating world of ideas opened up for Taneja as she read and discussed texts that talked about Marxism, postcolonialism, and other theories of modern life, and began to understand how these ideas filtered down through the stories we tell one another, and the way that people search for meaning in the day to day.

“It was a way of understanding the world through literature and seeing some of the biases and some of the things that exist on a deeper level, and knowing that even in, say the 1940s, when equality wasn’t a thing, there were some people who were progressive enough, who wrote about women as full-fledged characters,” she said. “Literature always gives you the hope that better things are possible. I am personally not an optimistic person, so literature helps me balance that out. Even though most of the stuff that I read is sort of tragic, there is always a sliver of hope in there somewhere.”

It’s this life-changing power of books and stories that compelled Taneja to continue studying English at Emory University, where she received a MA and PhD in English. For her doctoral dissertation, she focused on the partition literature of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and the way that objects have played a central role in the lives of those who have lived, and continue to live, through decades of upheaval in the area.

“A lot of my work has to do with trying to discover

that part of myself, because I come from a family that underwent partition. Both sides of my family were in what is now known as Pakistan, and a lot of those stories I couldn’t get access to directly because my grandparents had passed, so I’ve gotten many of those stories from the objects that my family has and the stories that they associate with it,” she said. “That was the personal motivation that sparked that research, but more generally I’m interested in the idea of hierarchical systems in society, classes, gender, caste, race, and how those get influenced and reflected in post-colonial literature.”

COA is fortunate to have Taneja join the college as a new faculty member, provost Ken Hill said. “Her focus on postcolonial literature, South Asian studies, and digital humanities will expand and strengthen our curriculum. We are delighted to have her join our team.”

Taneja is excited to be working within COA’s interdisciplinary pedagogy, for the many possibilities of a humanecological perspective, and by the highly engaged nature of COA students.

“When I interviewed here I was pleasantly surprised by the fact that students were a part of the process, how they were asking questions, and how very active they were with it,” she said. “I hadn’t seen that before, and I was appreciative of that fact because I remembered being one of those invisible students in school.”

Taneja is the recipient of a number of awards, including the QTM Advanced Graduate Completion Fellowship, Department of Quantitative Theory and Methods, Emory University. Her publications include; “Partition: Oral Histories” (Postcolonial Studies @ Emory); and “Book Review: This Side/That Side Restorying Partition: Graphic Narratives from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh curated by Vishwajyoti Ghosh” (Postcolonial Studies @ Emory).

In her free time, Taneja enjoys spending time with her kitten, Syaah, and rooting for the Atlanta United Football Club. She is enjoying exploring Bar Harbor and getting to know Acadia National Park.

New faculty Jonathan Henderson, music

By Jeremy Powers ’24JONATHAN HENDERSON turns on his Zoom camera, unmutes his microphone, and gives a thumbs up. Instruments hang on the wall in the background, a few guitars, a fretless bass, and the bookshelf to his right stretches up to touch the ceiling.

College of the Atlantic is pleased to welcome Henderson as a new faculty member in music. He plays bass, percussion, piano, and guitar, and brings a unique insight into how social structures and music interact and affect one another. His experience as a teacher and professional musician show his love and dedication to the craft, and he is excited to begin teaching at COA.

“I’m really interested in interdisciplinary work, and as an ethnomusicologist I’m interested in the intersection between music, anthropology, politics, and history. COA feels like a great place to be able to teach at those intersections and collaborate in a creative way with students and other faculty members,” he says.

Henderson completed his graduate work in ethnomusicology at Duke University and worked as an instructor and mentor in the departments of music and African American studies there. He has a range of teaching experience, both in secondary and higher education settings, and his is a student-focused teaching philosophy.

“A lot of my work begins with what interest students have in music and working out from there,” he says. “I think the best teachers are life-long learners, and I love being in the classroom because I’m always surprised by what a student shares, or I’m caught off guard by a piece of music that they bring in that I’ve never heard.”

Watching students grow as musicians is another thing he loves about teaching. “I know that through my work they’ll figure out ways of incorporating music into their lives going forward, and learn skills that they can apply to everyday situations,” he says.

Henderson has some plans in the works to expand the musical offerings at COA. One project is to start using a newly renovated recording studio on the second floor of Gates Community Center, an effort led by COA audio

visual technology specialist Zach Soares ’00 which has been in the works for a while. “It’ll be great to have students creating podcasts in the studio, recording original music, and just getting in there to learn about this technology,” he says. He is also hoping to start a Brazilian percussion ensemble in the fall term.

COA is delighted to add Henderson to the faculty, provost Ken Hill said. “In the coming years, Jonathan will teach courses on ethnomusicology, studio recording, composition, and applied instrument training. His broad musical training spans multiple regions and historical genres, and will be most welcomed in our community.”

In his musical life outside of teaching, Henderson has a band called Kaira Ba, which is a collaborative project with Senegalese musician Diali Cisshoko. “We’re still going to try to remain active from a distance. We have a few things happening this year that I’m going to fly in for, and in the summer, we’ll be collaborating more closely. We’ll be playing at the Ossipee music festival in Maine, down near Portland in the summer, in July.” Additionally, Henderson recently premiered a piece titled Anechoia Memoriam, “which is a participatory installation for a typewriter that electro-mechanically controls a grand piano. The score for this piece is composed of over 150 names of people of color killed by law enforcement in the United States, so it’s designed as a participatory memorial,” he says.

In his free time, Henderson enjoys getting outside with his family and exploring the Maine coast. “I also love cooking and baking, which seems to square pretty well with Maine winters,” he laughs. He also, of course, enjoys listening to music, and since he’s moved here, he’s had a certain piece on his mind. “I’ve always loved visiting the ocean, but I’ve never actually lived in such proximity to the ocean before. I’ve been thinking recently about a piece called Become Ocean by the composer John Luther Adams, which is an orchestral work that is very textural and is composed around the idea of energy building and releasing through the development of waves. It’s just a series of several waves kind of swelling and receding. It’s maybe 40 minutes long, and I’ve been thinking about that since being here, so I’ll have to put it back on and listen to it again,” he says.

David Gibson, director of energy

By Jeremy Powers ’24COLLEGE

OF THE ATLANTIC director of energy David Gibson brings extensive experience working with renewable energy in the public sector, the private sector, and as an energy educator. He is excited to engage with students through COA’s interdisciplinary approach, and is already helping the COA community realize their ambitious renewable energy framework.

“I worked for an educational nonprofit for five years out in Reno, Nevada and really enjoyed working with students and teaching the next generation the tools and skills they’ll need to address the climate crisis and transition off fossil fuels,” Gibson says. “COA’s mission to eliminate fossil fuel use on campus by 2030 really drew me in, and made me want to be somewhere that aims to be a leader and demonstrate that to the community.”

In his first months at COA, Gibson has jumped head first into bringing the college’s green energy goals to life. The college recently bought 11 units of off-campus housing, and Gibson immediately began coordinating installation of heat pumps and improving the insulation of the buildings. “Every building that we add insulation to, we’re saving money in the short term and saving carbon pollution in the long term,” he says. “If we don’t address our existing building stock and make it more efficient, we’re just going to continue wasting energy 40, 50, 100 years from now.”

Energy-use literacy and awareness is something that Gibson is working to bring to COA, partly through real-world, practical applications and partly through in-class learning. He’s taught two classes, one with math and physics professor David Feldman called Math and Physics of Sustainable Energy and one called Green Building Through the Lens of LEED, the latter in which students had the opportunity to work on sustainability projects on campus and have a meaningful impact outside of class.

“I’ve been working directly with students on some of the energy projects and see the same thing happening in other aspects of managing the college, and to me that’s just such a wonderful, real-world experience

where you’re learning about stuff in classes and then being able to apply it,” he says.

Gibson founded Powered by Sunshine, a nonprofit working to put Nevada on track for 100% renewable energy by 2040, and he worked for Envirolution (through Americorps VISTA) teaching K-12 students about energy efficiency and literacy. “The effort to educate students to be smarter energy consumers, I just see as really essential towards transitioning our building stock,” he says.

He also serves as the vice chair for the Sierra Club Maine Chapter, and in this position has successfully led efforts to pass two energy-related bills in the Maine legislature in 2021. LD1659 requires Efficiency Maine, a quasi-state agency, to provide more affordable avenues for efficiency and clean energy projects, and is focused especially towards low-income communities and communities of color. LD99 requires the Maine State Treasurer and Maine Public Employee Retirement System to fully divest from fossil fuels by 2026. “Essentially, over the next 20 years, Maine is going to have to invest at least $40 to $50 billion to transition off of fossil fuels… and we can see a return on investment for, ideally, the homeowners and building owners,” he says.

Gibson holds a BS in civil engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute, is certified LEED AP BD+C by the Green Building Certification Institute, US Green Building Council, is a Certified Energy Manager by the Association of Energy Engineers, and holds a Permaculture Design Certificate.

Gibson has transitioned two homes entirely off of fossil fuels, including a post and beam farmhouse built in 1828. He owns a homestead with his wife, Willow, and the two of them are implementing a permaculture plan there. They have planted a nut grove with chestnuts, heartnuts, pecans, and hickories, and a fruit orchard with apples, pears, peaches, plums, cherries, and a variety of berry bushes. He enjoys hiking, mountain biking, alpine and cross country skiing, snowshoeing, paddling, and other outdoor activities.

April Nugent, manager, Peggy Rockefeller Farms

By Jeremy Powers ’24IT’S A MILD, SUNNY DAY as April Nugent picks her way across a field at College of the Atlantic Peggy Rockefeller Farms, eyes peeled for hidden cow patties in the knee-high grass. As she walks, she points out some of the geography—the brook that splits the farm in two, the sheep pasture, the yellow farmhouse, and the gray barn that sits back from the road. A wisp of breeze rustles the leaves of the oaks and aspens at the edge of the field; a cow lows softly as it works through a patch of grass.

Nugent, the new manager of Peggy, as it’s affectionately known, has been around farm animals most of her life. From the age of eight, her family raised chickens, turkeys, geese, and goats. Being involved in the everyday care of these animals and marketing the farm’s products sparked her interest and set her path in life, she says. She’s loved combining farming with education since her days at Hampshire College, and looks forward to doing so in COA’s interdisciplinary environment.

“I like working and living in environments with a focus on asking big questions and challenging the current way of doing things,” she says, “and farming and caring for the land and the animals makes me feel empowered to make meaningful change in the world and gives me a sense of purpose.”

Nugent is an alum of Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she studied sustainable agriculture with a focus on livestock management. She explored many facets of agriculture at Hampshire, including food systems, animal physiology, dairy herd management, environmental ethics, and farm business management, and even managed to work in an oil painting class or two, she says. After graduation, she became Hampshire’s grass fed livestock operations manager with a specialization in rare breed swine genetics.

“We are super lucky to have April,” says COA administrative dean Bear Paul. “She impressed everyone throughout the interview process, and she’s been even more impressive on the job. CJ Walke did a wonderful job establishing COA’s operations at Peggy, and April has come in and built off the work CJ did. April has really made Peggy her own and has some super exciting ideas that she’s making happen.”

Nugent has known about COA for a long while and says that the college has always spoken to her.

“I had looked at COA when I was a prospective student, but I opted to stay closer to home,” she says. “I’ve stayed interested in COA ever since, so when this opportunity came up, I just knew it would be the perfect fit. ”

The 125-acre Peggy Rockefeller Farms is operated as both a production and educational facility, with a handful of workstudy students employed there during the academic year. Classes such as Agroecology, Wildlife Ecology, and COA Foodprint make use of the farm, and students can use the property for class projects and independent studies.

Nugent looks forward to expanding on all of the educational opportunities the farm holds and tying the farm and the academic program together more directly. She’s also working to improve systems and better balance the work and study portions of workstudy positions on the farm. During her first winter at the college, she teamed up with COA Partridge Chair in Food and Sustainable Agriculture Systems Kourtney Collum to teach a course on farm animal management.

New trustees

By Rob LevinJOYCE CACHO

with fellow trustees, she hopes that COA will become a post-COP 26 leading education institution by embedding Environmental, Social, and Governance and Task Force on Financial-Related Financial Disclosures metrics into its operations and finance policies to capture COA’s culture and goals.

Drawing from a rich familial legacy of engagement and investment in education, she was additionally drawn to COA’s innovative and integrative approach to teaching.

Cacho and her husband recently moved to Massachusetts and enjoy summer sailing in Rockland, ME. She enjoys hiking, snowshoeing, tennis, golf, and volunteering to support ecosystem and community health. Joyce’s Cardamom and Crystalized Gingerbread Pudding is a family favorite!

HEATHER RICHARDS EVANS

“WE’RE STANDING AT A CROSSROADS,” is how our new distinguished trustee Joyce Cacho, PhD described why she joined the board of trustees for the College of the Atlantic. “COA has incubated how tertiary education should be done, which is particularly valuable during this moment in time defined by a global pandemic and racial reckoning for which the US is the epicenter.”

Uniquely suited for this moment and opportunity, Cacho is a change catalyst who brings broad and deep expertise to the board, coupled with a clear and dynamic vision for COA’s future. Fluent in five languages, she has leveraged her background in multiple industries nationally and internationally, including Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America. She is a recognized leader in innovation, growth and business culture transformation, while also being a passionate sustainability advocate by meaningfully embedding ESG enterprise risk management in business growth strategy.

Cacho notes that COA’s history, vision, and numerous accolades, which include being the first college to be carbon neutral, one of the first to divest fossil fuel holdings from its endowment, and being named the greenest college in the country by The Princeton Review, align with her own experience, vision, and passion. During her time with COA working

“COA is exemplary of education that prepares our talent pipeline for the US and abroad, where integrative thinking and respect for ‘other’ is paramount in both business and personal decisions,” says Cacho. Cacho hopes that COA will work to normalize BIPOC and other currently under-represented communities throughout the complexity of private and public education. Doing so is integral to COA being a welcoming, inclusive ecosystem and a champion of normalizing the broad base of diverse perspectives that student populations bring, and which is required of course and academic program content today.

Passionate about financial accounting governance and its role in creating business and community resilience, Cacho is a board director of Sunrise Banks, NA, an OCC-US Treasury regulated financial institution, one of 950+ Community Development Financial Institutions, a Certified Benefit Corporation with national and Minnesota charters, and a member of the Global Alliance for Banking on Values. The bank offers financially inclusive products and embraces social entrepreneurship and innovation on the cutting edge of the rapidly emerging fintech industry across the country.

Previously, she served as a board director of Land O’Lakes, Inc., a Fortune 200 company and one of the nation’s largest farmer cooperatives. She is among Savoy Network’s 2017 and 2021 Most Influential Black Corporate Directors, and Directors and Boards Magazine’s 2018 Directors to Watch

HEATHER RICHARDS EVANS is founder and president of Yaverland Foundation, which supports conservation, education, and the arts, with a particular focus on programs benefiting underserved communities.

Evans has broad experience in governance, strategic planning, and master planning. She enjoyed practicing law as a litigation associate in New York prior to moving to London where she lived for 10 years before returning to the US. After a brief stint in Connecticut, Evans now resides in Delaware. While in London, Evans was active in strategic planning for the American Friends of the British Museum, Business in the Community, and West London Action for Children. Her board service, as well as her ad-hoc work, are informed by the communities in which she lives and complement Yaverland’s mission.

Evans served for a year in an advisory role on the COA Buildings & Grounds

Committee before her election to the board. She is excited to have the opportunity to work with the diverse and talented group of individuals comprising the COA community in exploring our collective understanding of human ecology.

“I’m energized by the challenges and possibilities of building upon the vision of COA’s founders 50 years ago as we proceed together in strengthening a framework that supports the exploration of what it means to be a world in balance,” she said.

Evans is a seasonal resident of MDI. In a mobile world, Northeast Harbor has always been the place where she, her three adult children, extended family, and friends can reliably find each other and renew their sense of wonder.

Evans has an AB in history from Princeton University and received her JD from NYU School of Law. She completed additional graduate work in environmental planning at the University of Pennsylvania. Evans is a member of the New York and New Jersey State Bar associations.

CHANDREYEE MITRA ’01

first crew of students to spend a summer on Great Duck Island, where she researched Herring Gulls, an experience that she credits with shaping her subsequent passion for scientific research. “I love COA as an institution and firmly believe in its mission and vision,” she says.

Mitra takes a whole-organism and interdisciplinary approach to her research, using tools from animal behavior, physiology, anatomy, and evolutionary biology. The central goal of her work is to explore how observed behavioral and physiological traits are affected by changes in environmental variables.

An associate professor of biology at North Central College, where she has taught since 2015, Mitra probes these areas using two very different animal systems—field crickets and butterflies.

“My work with field crickets has focused on the idea that adaptive phenotypic plasticity is one way for species to persist in variable environments,” she says. “Specifically, I have examined aspects of the environmentally mediated life-history trade-off between flight and reproduction in different polyphenic morphs.”

Through her parallel work with swallowtail butterflies, Mitra has focused on the costs and benefits of male nuptial gift giving. In many butterfly and moth species, males take in salt from the environment and transfer it to females during mating. Mitra’s work examines how salt availability affects male behavior and fitness, and how variation in male-provided salt affects the fitness of females and their offspring.

As part of that first crew on Great Duck, at what would become the Alice Eno Field Research Station, Mitra credits her time at COA with sparking a lifelong passion for scientific research.

“My time on Great Duck, especially doing research with John Anderson, helped me find my path to becoming a researcher working in animal behavior. And that eventually led to my seeking a position teaching at a small liberal arts school where, like John did for me and so many, I could introduce undergraduates to the wonders of scientific research.”

Mitra holds a PhD and an MS from the University of Nebraska School of Biological Sciences. Previous to her current appointment at North Central, she served as assistant professor of biology and coordinator of the environmental studies program there. She has been a National Institutes of Health Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award Fellow, a graduate teaching and research assistant at the University of Nebraska, a field assistant at the University of California Hastings Natural History Reservation, and a wildlife biologist at the Lassen National Forest. Her research has been published in Animal Behavior and Ecological Entomology. Mitra has presented numerous times at the Animal Behavior Society Annual Meeting, the National Conference on Undergraduate Research, and the Midwest Ecology and Evolution Conference, among others.

BIOLOGIST CHANDREYEE MITRA ’01 has been a dedicated fan of College of the Atlantic since she attended school there back in the late 1990s. She was part of the

She writes, “Human activity is changing the abiotic environments of many extant species, and how a species responds to such changes may affect its persistence in a changing world. One nearly instantaneous way animals can respond to changes in their environment is by changing their behavior. Therefore, my students and I have been working on how organisms adjust their behavior based on the surroundings they happen to find themselves in.”

Public outreach efforts are a big part of Mitra’s career. She helped celebrate Monarch Madness at the Growing Place, coordinates Project BudBurst at North Central, and has organized display tables at the Insect Festival, the WonderLab Museum of Science, Health and Technology, and University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, among other efforts. She is a member of the Animal Behavior Society, the Association for Biology Laboratory Education, Sigma Xi, the Society for the Study of Evolution, and the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

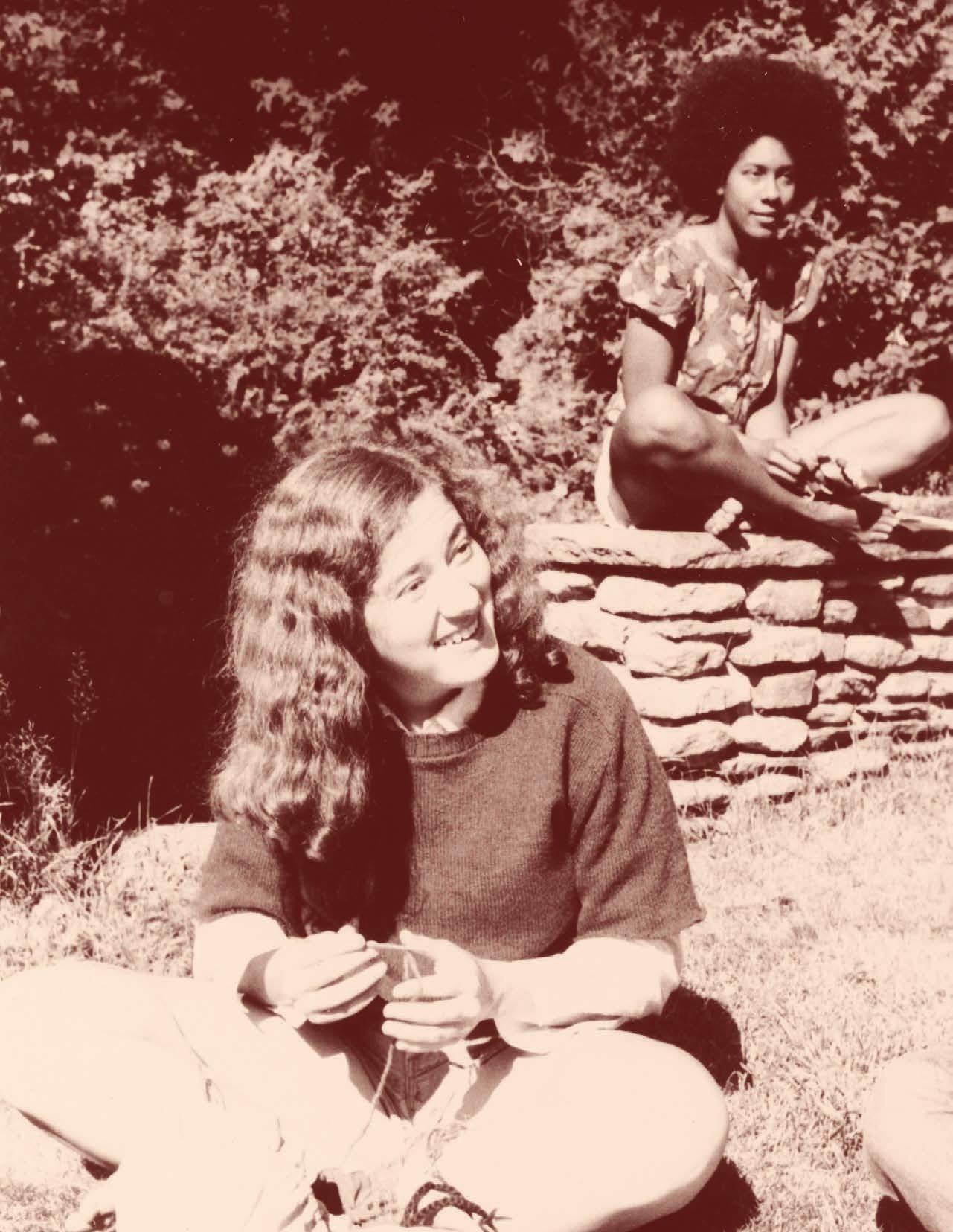

Goldsworthy comes to COA

ENGLISH

SCULPTOR, photographer, and environmentalist Andy Goldsworthy visited COA in the fall of 2021.

Goldsworthy gave a fascinating and wide-ranging talk and slide show featuring art he created during the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020 and 2021. While most of the world was hunkered down working remotely, Goldsworthy was engaged in creating work in and around his property in Penpont,

Scotland. For Goldsworthy, who is used to traveling internationally to create work, being locked down was something new but also oddly rooted in how he approaches working: “I’ve always said the best way to understand change—and my art is about change—the best way to understand change is by staying in the same place.” The following quotations are from Goldsworthy’s talk at COA.

“It’s not like these works are illustrating some political view. They are about trying…they come out of trying to figure things out, which is what I do when I make art. I’m trying to figure things out, trying to understand what’s going on. What’s in front of me, the weather, the light, the stone.”Left: Andy Goldsworthy, Watershed (detail), 2019. Installation at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.Courtesy: Galerie Lelong. Right: Plaque at the base of the wall, Storm King. Credit: Catherine Clinger.

“The way something changes and decays is as important as the way it’s made. And I learn as much about the material and the place as it decays as when I make the work. And that is the essential driving force… It is the reason why I make my art.

When I make things, I learn about them, I understand them, I have a connection to them. It’s a knowledge that can only be gained by touching and by working. I’m not trying to improve what is there, I can’t do that, but I do feel this deep need to be involved in the land.

As I said before, It’s not like I’m trying to illustrate some political or environmental issue with my work. The work is an environmental issue. I am an environmental issue. I live and breathe that.”

“There’s always this leap into the unknown for me… But it’s quite extraordinary, the solutions that can arise.”

College of the Ecstatic

By Terry Tempest Williams

By Terry Tempest Williams

“IAMECSTATIC to be here,” I recall a student saying to me on my first visit to COA.

From that day forward, I have called College of the Atlantic, “College of the Ecstatic.”

My husband Brooke and I had been invited by Steven Katona and his wife Susan Lerner for a tour of the college in 1999. Steve was president of COA, as well as being one of its founding faculty members as a biologist.

The setting was impressive, a learning community on Mount Desert Island devoted to human ecology with a shimmering view of the Atlantic Ocean from campus. We had just come back from an inspiring lunch when a puppet procession led by large, imaginary animals and comical birds was underway. We followed the procession through the woods. At its helm was the creator—Eli Nixon ’99.* We were led by the beasts down trails to the small cove as panels of text soared from the pines above and were pulled dripping from the bay by way of zip-lines. A wild band of horn players accompanied the pageantry with music composed by another student, Nikolai Fox ’00. Word had it that various students trained in forestry and agro-ecology were now draped in paper maché receiving theater directions from Eli. It was all a grand, feral pageant: an epic Battle Between Hope and Fear.

Later that afternoon, we listened to students speak about their senior projects. The puppet theater we had experienced outside was expanded inside as Eli spoke of art as a vehicle for social change capable of illuminating our relationship with Nature, interconnected and interrelated. As they spoke, the field of human ecology was cracked wide open. I not only saw a brilliant student courageously engaging with the world with their original vision, I saw a leader who transcended

categorization. They not only spoke about what was possible, but necessary through igniting the imagination.

I asked Eli if they would come with their band of puppets from College of the Ecstatic and accompany me to Fire & Grit, the Orion Society’s gathering of writers, educators, and public policy makers to be held at the National Conservation Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

Eli accepted the invitation. A month later, we organized an artistic coup.

As an invited writer, I had been given 30 minutes to speak. I yielded my time to Eli and their troupe without warning government officials. A revised Battle Between Hope and Fear with banners flying across the auditorium ensued. They brought the house down. These students from COA bypassed rhetoric and touched the heart. One of the lasting images for all of us was seeing the dignified Barry Lopez dancing with a 10-foot tall carrot as he wore the paper maché husk of a rhinogahog.

Today Eli Nixon continues their work as a cardboard constructionist and educator, activist, and creator of magic in schools and community centers around the country. After two decades, we are back in touch and once again, Eli has agreed to collaborate. We will gather at Cape Cod on a beach with Harvard Divinity School students and discuss Eli’s new book, Bloodtide: A New Holiday in Homage to Horseshoe Crabs. It will be another portal of possibilities we can walk through together.

I think of Samantha Haskell ’10, a young agrarian who is now the owner of the revered independent bookstore, Blue Hill Books. She has not only built on the bookstore’s solid tradition of being smart and savvy, she is activating an intellectual community of care within the next generation of residents and readers in Hancock County in Blue Hill, Maine.

*Eli Nixon ’99 formerly used the name Beth. Their book is available for order through 3rd Thing Press and Samantha Haskell ’10 is happy to order it for you at Blue Hill Books.

*Eli Nixon ’99 formerly used the name Beth. Their book is available for order through 3rd Thing Press and Samantha Haskell ’10 is happy to order it for you at Blue Hill Books.

Samantha writes:

As students, our line was always, “Human ecology is everything,” which is both hyperbolic and true. The context of the human’s relationship to the environment is all-encompassing, particularly in the anthropocene, but it also includes us as conscientious observers. The concept is expansive, overwhelming, and liberating; find the thing you’re most interested in, whatever it may be, rest assured it is relevant, and now explore it deeply, critically, thoughtfully. This is human ecology in action.

For me, it was rural communities. How do we define a sense of place? What brings us together? This became courses in landscape architecture, American literature, ornithology, and environmental law. Then an exploration of the communities near national parks around the world. After graduating, it bloomed into running the independent bookstore in my hometown, and becoming president of the local land trust. I hope that I’m helping to advance and meld those traditions today in the place that I love.

And close to home in my own state of Utah, I think of Ky Osguthorpe ’19, who is now the government grassroots liaison for the Utah Rivers Council. We met recently at the Save Our Great Salt Lake rally. Like Eli and Samantha, Ky is passionate about her work, even as it involves embracing grief alongside her love as she witnesses the Great Salt Lake disappear into a horizon of salt.

Ky writes:

The air of mystery around human ecology is intentionally cultivated by professors, their courses, and the inescapable final assignment of the school, the Human Ecology Essay. This assignment gives students an opportunity to define human ecology, a seemingly odd task for students who have ostensibly spent four years studying the subject.

Like most of my peers, I had a difficult time figuring out what to write. I ended up writing my essay about leaving Mormonism and feeling isolated, stuck in a chasm between people who hate the LDS church and those who belong to it, and trying to figure out what kindness meant through it all. I equated human ecology to the rivers that flow between such chasms. I wrote, “To seek connection is to participate in human ecology, to believe, in the face of deep canyons, that there exists something exciting, something dynamic and stochastic between the world’s stubborn monoliths of false certainty.”

So here I am, an ex-Mormon, river-loving human ecologist. I look at the impossibly high walls on either side of myself, feel the depth of the chasm in which I stand, and remember that between towering evils, good and truth reside in meandering cracks.

This is why College of the Atlantic is singular—passion gives rise to hope where students can put their love into

action. “It’s an Ivy League education that cares about our relationship to the Earth and all its inhabitants in all its diversity,” Steve Katona, now president emeritus, told me so many years ago. I see this same kind of leadership continuing through the exuberance and generosity of spirit with President Darron Collins ’92 and COA’s committed faculty and staff.

The testament to being awake, alive, and engaged in this liminal moment of climate collapse and a global pandemic resides in the pragmatic vision of our young people. Eli Nixon, Samantha Haskell, and Ky Osguthorpe are examples from the COA student body and alumnx who are not only “finding beauty in a broken world” but creating beauty in the world they find.

On this 50th anniversary celebration of College of the Atlantic, I still see this small college on Mount Desert Island as College of the Ecstatic, where the embodied intellectual life at COA encourages each student to become their highest and deepest selves, be it through a pageantry of puppets, owning an independent bookstore in rural Maine, or protecting the shrinking Great Salt Lake in the climate of now.

Isidora Muñoz Segovia ’22

THERE WERE MANY THINGS that attracted me to COA when I applied. I was looking at schools in Europe and not really considering the US as a potential home for four years of my life. However, right when I thought I had made up my mind to study in Ireland, COA came into the picture. It was the small college, tight-knit community, and nature-oriented education that mesmerized me. This was not what I thought the US could

NUTRITIONAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Before coming to COA I knew I wanted to focus on something related to environmental politics, Indigenous knowledge, and climate change. Throughout my time at COA, I have learned that a way to combine all of these passions is through the study of food systems. Nutritional Anthropology taught me so much about human history, how we relate to our food, how evolution reflects our society’s eating habits, and how intertwined that is with our culture and identity. This class made me even more interested in the science behind the chemical reactions of different foods. I really enjoyed how Kourtney Collum taught this class because I felt that by the end of the term I had learned so much and I was eager to continue learning more.

offer in terms of colleges.

I think one of the biggest factors that attracted me to COA was its location and the degree in human ecology. I knew I needed a lot of greenery close to me, and Acadia National Park seemed like a real-life dream. Human ecology looked like the perfect combination of everything I was interested in, mostly because it allowed me to create my own focus. The problem was,

right when I realized COA was perfect, I also realized I wanted to take a year off to gain realworld experience. After getting accepted to the college, I asked to defer for a year and COA agreed. It could not have worked out more perfectly; in my gap year I gained many skills I would find myself using as a student at COA.

GARDENS & GREENHOUSES: Theory/Practice of Organic Gardening

This was an amazing class because it was the perfect mixture of hands-on experience that I was so eager to get from COA, a super interesting syllabus, and a really great class dynamic, which was so important during the first pandemic term. One of the coolest things about this course, taught by Suzanne Morse, was that, due to the nature of being remote, each one of us had completely different climates we were using to grow our orchards. My parents were really excited about me redesigning our garden into a beautiful edible green space!

STUDENT SCHEDULE

DEPT/ID COURSE NAME

ES 1014 Gardens & Greenhouses: Theory/Practice of Organic Gardening

ES 2040 Introduction to Forestry

HS 3095 Nutritional Anthropology

Morse, Suzanne

Morrell, Hale

Collum, Kourtney

Monday/Thursday

Tuesday

Tuesday/Friday

INTRODUCTION TO FORESTRY

Introduction to Forestry was taught by Hale Morrell ’12 and, similar to Gardens and Greenhouses, it was a great mixture of hands-on experience and more traditional class time. This class truly opened my eyes to an area that I don’t often think about when considering climate change and sustainability. Forest management is such an important topic that you don’t usually learn about in school, unless you are very interested in it. I really enjoyed the special guests—professionals in the field from Maine and around the world. In particular, I really enjoyed our class with Matheus Couto who works with Brazil’s UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Couto gave a fascinating talk about agroforestry, reforestation, eucalyptus, and GMOs in Brazil.

PICTURE WAS TAKEN during my fi rst term at COA in one of my favorite classes, Ecology: Natural History, with Steve Ressel. The class went on a field trip to Borestone Mountain and spent a night camping by the river as we immersed ourselves in the ecology of the site. I had a hard time choosing only one picture because there are so many treasurable moments at COA. I was able to gain fi rst-hand knowledge about Maine’s ecology through the course. This grounded me with a sense of place and was exactly the type of experiential class I was looking for when I applied to COA. DAYS

CREDITS 1 1 1

Just doing my part

Ursa Beckford ’17 interviews US Rep Chellie Pingree ’79

WITH A NEW ADMINISTRATION comes new challenges and new opportunities. What does it mean to work in government after the challenges of the last administration? For US Congresswoman Chellie Pingree ’79 it means remembering your roots while becoming chair of the House Appropriations Committee Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, one of the most powerful positions in Congress. Ursa Beckford ’17 brings us this insightful interview with the congresswoman.

I’ve been focusing on those issues in the infrastructure packages we are working on right now.

Similar to how it was framed in the Green New Deal, you can’t just talk about environmental issues and leave out people. It can’t be just about the environment. You have to think about environmental justice and then you have to think about people’s everyday lives. How do people get to work? Do they have childcare? Do they have health care? Are their own lives manageable and healthy? Do they have housing? Really, the things that people confront every single day in Maine. So I think I always look at it through that lens. How are we going to do this and make sure we also are thinking about people?

When people ask me about human ecology, I tend to say, It’s not just a funny degree with a complicated name… It’s actually how you take some of these science-related issues and think about them from a human perspective.

UB: That’s fascinating, because I think human ecology is often defined as the study of the relationships between humans and their natural or social environments, meaning someone might focus on one or the other. But you see them as integrated.

CP: Yeah, part of the difference is that once you’re out of college you’re trying to implement what you learned... So you have to think about everything.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC

UB: How does COA continue to influence you?

URSA BECKFORD: To start off with, what are you focused on right now? What makes you get up in the morning?

CHELLIE PINGREE: Well, as a member of Congress, every day is a little bit different. One of the challenging, but wonderful, things about this job is you wake up in the morning and you’re often facing a day completely different from the day before. We do everything from deal with challenging constituent issues to internal debates and negotiations within our own party. We have committee meetings and hearings, we’re working on bills, we’re voting on the floor. But overall, I’ve always worked on some of the same themes. I’m an organic farmer in my other life, so everything about farming and food systems has been at the forefront for me. We’re doing a lot of work on climate change and its relationship to agriculture. So

CP: You spend a fair amount of time in college and you learn things that you don’t know you’ll use until much later in life. I learned a lot of different things that still impact my life. I even took a couple of business classes, I took basic bookkeeping. I don’t know how I snuck that class in, but I’ve run a small business most of my life, so I still lean on a lot of that knowledge.

I was at COA the other day. They were opening up the Davis Center for Human Ecology, and I was very excited because it’s such a green building and my committee oversees the Forest Service budget, so I’ve been interested in funding a lot more forest product innovation. One of the things about that building is they used wood fiber insulation, a new product that’s going to be made by GO Lab, a company in Maine, using a German technique to repurpose wood byproducts into environmentally friendly insulation material that is really efficient.

We’ve had somebody from GO Lab come and testify at agriculture hearings to talk about how to have a sustainable forest and how

a product made out of wood holds onto carbon, which then stays in the building and becomes a carbon sink for a long time. I think this was the first time that they’d used wood fiber insulation in a building on a large scale, and it’s at COA. So it’s nice how it all tied together for me. COA is doing a lot of really great stuff that is topical for what we’re working on today. I feel really connected to the things happening at the college.

UB: What was it like to be back on campus?

CP: I found myself talking to another alums and saying, When I was here, it was before this building burned down... And I sort of felt like one of those really old people who’s like, Yeah, in my day we only had one building...

When I first got there in the 1970s, we didn’t have on-campus housing. There was just a weird little motel down the road they rented for students… It was like a horror movie motel. You could share a tiny, gross, smoke-filled room with a roommate. So very quickly a couple of my friends and I found a place to rent in town. Today, I feel like I’m talking to people who can’t even conceive that it was the same college when I was there. But I just love the fact that it’s grown, it’s become a college with a lot more resources and more opportunities. It’s great.

UB: How has human ecology influenced your life and work? I imagine you’re the only powerful congresswoman with a degree in human ecology. Do you notice that you bring a different perspective?

CP: I’m sure I’m the only congressperson who has this degree. I think it’s a combination of that degree, but also coming from Maine, where I don’t think people separate the natural world from our daily lives as much as you might in some other places. You can go up to anybody in Maine and start a conversation about the weather. When you live in a rural area or area impacted by weather, people talk about it all the time. And that may seem incidental, but it’s a reflection of the fact that people pay attention to what’s going on outside. A lot of Mainers are much more aware of things like, Have the trees changed? What season are we in now? A huge percentage of Maine people burn wood to heat their houses. They have a garden in their backyard. They can’t wait to get outdoors, whether they’re hikers or hunters or cross-country skiers. Some people really like going fishing or being

on lakes… That’s always given me this perspective that everybody has an equal amount of concern about their lives because their lives are rooted in nature.

BACK TO THE LAND

UB: Did you bring that human-ecological perspective to COA, or did it develop there, or later on?

CP: I chose COA because it was a college in Maine that represented some of the things that interested me, but it wasn’t as if I grew up in life thinking, I want to be an environmentalist. Before I went to COA, I had been living in Maine for a couple years and was a back-to-thelander, which really hadn’t been my plan in life either. I grew up in Minneapolis, went to an alternative high school in Massachusetts, and then followed a boy to Maine. I was reading Helen and Scott Nearing’s books, and I decided it was something that made a lot of political sense… It was a way to differentiate yourself from what the establishment was doing. We had a government we couldn’t trust, sending our friends and siblings to Vietnam, and you had to live a life to show that you were protesting the status quo. So even though I didn’t know much about how to run a wood stove or can tomatoes or anything, it just somehow all flowed.

So I guess I brought all of that to College of the Atlantic when I got

Representative Pingree at the dedication of the Congresswoman Chellie Pingree ‘79 Greenhouse, part of the COA Davis Center for Human Ecology.there, and it colored what I wanted to study. I wasn’t interested in going to a school where you had a lot of required classes that you had to take… I was sort of done taking classes the way I had in high school. Being able to focus on what I wanted to do and figuring out how all those things fit together was pretty useful.

UB: So it seems like your views on human ecology are really related to your core interests in Congress and they go back to those early days.

CP: When I was at the college, I mostly focused on growing things, growing plants. Eliot Coleman, who sort of became the guru of organic farming, taught a few classes... I instantly gravitated to being a farmer, having an organic farm, living a rural life.

By the time I ran for the House, I had, one way or another, either been a gardener or had a small farm, or had a small business related to farming, all my life. I served for eight years in the Legislature, where I focused more on health care, prescription drug prices, things like that. When I got to Congress, there were a lot of members who were very focused on health care, and it’s a big national issue. That’s when we passed the Affordable Care Act. But I literally found no one who was interested in food systems. There were a few people who supported organic farming, but it wasn’t their issue. So that really was when I just dove in and said, look, I know so much about agriculture, organic farming, the changing consumer market, what people want to buy, what they want to eat, what they want to feed their kids, toxins related to the environment—all those things. I was like, This is a void and someone needs to do this.

UB: What do you think your younger self would’ve said about you coming to serve in Congress? It’s interesting to hear about your earlier views on government, and here you are.

CP: Well first off, I literally had never engaged with the political process in terms of whether I was a Democrat or Republican, or how political parties worked, until a few months before I ran for the Legislature in 1992. I always voted, but I paid very little attention to it all. I’d never gone to a party meeting. And certainly when I was a teenager, I felt very alienated from government. I didn’t engage in it.

I really started to get interested in the process of governing on a local level because I live in such a small town. We have a town meeting every year in March, a form of government in and of itself. The entire town fits into a big room and takes a vote on every line item in the budget. And it really got me thinking much more about how the system works, how we govern. You weren’t abstracting it

because you think about it all the time. You talk to people in your town about it… You don’t think, Oh, that’s government and it doesn’t connect with me. It’s more like, What do I want to have happen in my future, in my kids’ future?

Eventually I was a tax assessor, then a planning board member, and then I was on the school board. That got me thinking about how you get the five people on the school board to agree about what you think is important for your kids. So I came into government and got comfortable with it in a totally different way.