FACULTY

AND STUDENTS

PUT PUBLIC HEALTH INTO PRACTICE

FACULTY

PUT PUBLIC HEALTH INTO PRACTICE

NICOLE BAYNE, MPH ’21, AND SUKHMANI KAUR, MPH ’24, ARE WORKING ON RESEARCH INVOLVING HOUSEHOLD CLEANING TECHNIQUES AND INDOOR AIR QUALITY.

The Applied Practice Experience (APEx) helps students gain an on-the-ground understanding of health systems and communities, allows them to explore the area of public health they are most passionate about, and provides an opportunity to apply what they have learned in the classroom to make an impact on public health at community, national, or global levels.

To ensure students of all backgrounds have the financial flexibility to pursue the APEx that is most meaningful to them, consider making a gift to Columbia Mailman today.

Make your gift today at publichealth.columbia.edu/give or contact Laura Sobel at ls3875@cumc.columbia.edu to discuss the power of leadership giving.

View the digital version at publichealth.columbia.edu/ CPHmagazine.

DEAN

Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH

ASSOCIATE DEAN AND CHIEF COMMUNICATIONS OFFICER

Vanita Gowda, MPA

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Dana Points

ART DIRECTOR

John Herr

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Tim Paul

COPY EDITOR

Emmalee C. Torisk

As part of our commitment to environmental stewardship, this issue is printed by The Standard Group on Rolland Enviro™ 100% recycled paper.

© 2024 Columbia University

CONNECT WITH US Alumni:

msphalum@cumc.columbia.edu publichealth.columbia.edu/alumni

SUPPORT US Development:

msphgive@cumc.columbia.edu publichealth.columbia.edu/give

WORK WITH US Career Services:

msphocs@cumc.columbia.edu publichealth.columbia.edu/careers

LEARN WITH US Admissions:

ph-admit@columbia.edu publichealth.columbia.edu/apply

2024–2025 EDITION

COLUMNS FEATURES

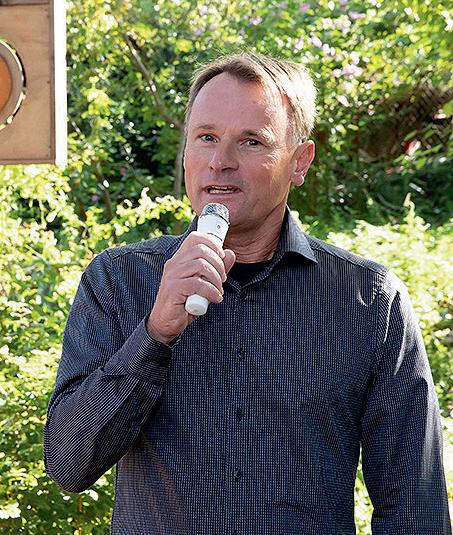

In her last year as dean, Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, discusses public health past and future with alumna Perri Peltz, MPH ’84.

16 Community at the Center

In the heart of New York City, the School offers community research and training experiences unlike any other. By Dana Points

22

Faculty and students are working hard to communicate about public health in the most effective ways. By Christina Hernandez Sherwood

28

Lead, arsenic, and other metals are all around us, with important health effects. By Caroline Wilke

As the School’s Program on Forced Migration and Health has its 25th anniversary, the need for its leadership has never been greater. By Jim Morrison

36

With a new professorship and Child Health Center for Learning and Development, the School is doubling down on children’s health. By Paula Derrow

After 16 years as dean of the wonderful Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, I plan to conclude my service in June 2025 and focus on my role as a faculty member and director of the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center. It has been my privilege to lead this remarkable institution and to help advance our community’s shared mission to build a healthy and just world.

I feel honored to have played a role in our School’s trailblazing history. For more than a century, the School has educated public health leaders, conducted groundbreaking science, and developed innovative solutions to protect and improve population health. Today, Columbia Mailman School leads in taking on the most pressing global public health challenges, including health inequities, the climate crisis, environmental threats to health, emerging infectious diseases, violence, the need for healthy longevity, and much more.

Since its founding, our School has been deeply intertwined with and dedicated to population health in New York City and the greater region. Over the years, hundreds of our graduates have gone to work for our city’s agencies and initiatives; two School deans have also served as commissioner of health of the city; and our faculty, staff, and students have conducted research, served on commissions, implemented programs, and more, throughout the city. Our latest endeavor, the Community Health Equity Collaborative, profiled in our cover story (page 16), will further strengthen our partnerships and contributions in Northern Manhattan and across our beloved city.

Telling our School’s stories through this magazine is always a highlight of my year.

One of the magazine’s goals is to engage our amazing network of alumni, donors, and friends who create meaningful change around the world. Thank you for your continued support of our School. And to all of our alumni, faculty, staff, and students: I am grateful for the opportunity to have been a part of your professional journey and our School’s significant contributions to the public’s health.

Wishing you good health,

Dean Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH

EXPOSOMICS, WHICH ANALYZES DATA FROM ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURES— PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL, BIOLOGICAL, AND PSYCHOSOCIAL—WILL TRANSFORM PUBLIC HEALTH MUCH AS GENOMICS HAS REVOLUTIONIZED MEDICINE. And the new Columbia Mailman Center for Innovative Exposomics promises to be a major player in the space. “Our genes don’t provide a complete picture of disease risk. Health is also shaped by what we eat and do, our experiences, and where we live and work,” says the new Center’s director Gary Miller, PhD, vice dean for research strategy and innovation and professor of Environmental Health Sciences. The exposome is the compilation of these factors.

The Center’s team, drawn from across the Columbia University scientific community, is driving discovery and innovation through the development of new methods and workflows to measure complex exposures in blood and other biological samples. Miller and colleagues are leading an

arm of a global study using exposomics to examine determinants of cancer in people of African descent. Other investigators are studying cancer, liver disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. (Miller was also recently asked to lead the new NEXUS [Network for Exposomics in the U.S.] Coordinating Center at Columbia University, with more than $7 million in National Institutes of Health funding.)

The Center for Innovative Exposomics partners with the Biomarkers Core Laboratory of the Irving Institute for Clinical Translational Research, the Columbia Precision Medicine Initiative, and the Data Science Institute. With links to the European Human Exposome Network, France Exposome, and the Expanse Project, the Center promises to be an international intellectual hub, connecting academia, industry, and government, to share information about this rapidly evolving field.

Epidemiology

trailblazer

W. Ian Lipkin, MD, marks 40 years in research and 50 in medicine.

Lipkin’s 40th Anniversary

Leading scientists from around the world convened last spring to celebrate the extraordinary career and transformative scientific work of W. Ian Lipkin, MD, the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology and the founding director of the Center for Infection and Immunity (CII). The daylong symposium marked Lipkin’s 40th year in research. Panelists, most of whom have collaborated with Lipkin for decades, highlighted Lipkin’s significant accomplishments, including the fact that he spearheaded the development of the technology of pathogen discovery used worldwide, which he has used to identify more than 1,500 viruses and advance science on serious outbreaks including West Nile virus, SARS, Zika, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2.

Recognition for Public Service

Diana Hernández, PhD, associate professor of Sociomedical Sciences, and Parisa Tehranifar, DrPH ’04, associate professor of Epidemiology, were inducted into the Academy of Community and Public Service.

Medical Center Award to Smith Gilbert Smith, administrative director at CII, received the Columbia University Irving Medical Center Baton Award, recognizing team players who contribute to the medical center’s success.

Llanos at the White House

Adana A.M. Llanos, PhD, MPH, associate professor of Epidemiology, was an invited participant at the 2024 White House Minority Health Forum.

5 Faculty Among Top 1,000

Dean Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, and four Columbia Mailman School colleagues are among the Best 1,000 Female Scientists in the World, as rated by Research.com. Elaine L. Larson, PhD, RN; Regina M. Santella, PhD; Frederica P. Perera, MPH ’76, DrPH ’82, PhD ’12; and Melanie Wall, PhD, all made the list.

Weissman Wins Award

Myrna Weissman, PhD, the Diane Goldman Kemper Family Professor of Epidemiology and Psychiatry, is the recipient of the Women in Medicine Legacy Foundation’s Alma Dea Morani Award, which recognizes a woman who has furthered the practice of medicine and made significant contributions outside medicine.

Fullilove and Rosner on PBS

Robert Fullilove, EdD, and David Rosner, PhD, MPH, professors of Sociomedical Sciences, were featured in The Invisible Shield, a PBS documentary examining public health’s role in improving lives.

THANKS IN GREAT PART TO THE FIELD OF PUBLIC HEALTH, LIFE EXPECTANCY HAS ROUGHLY DOUBLED SINCE 1900. By 2050, the number of people aged 80 or older is expected to triple. Society now faces the challenge of optimizing our longer lives by extending our “healthspan”—years of life lived free of disease and disability. Dean Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, has long been a leading researcher and advocate for healthy aging; now she is leading CHAI, the Columbia University Irving Medical Center Healthy Aging Initiative, a medical center-wide steering committee defining a new vision for aging research at Columbia. This spring, its Healthspan Extension Summit brought together 300 researchers and guests from across the medical center and beyond to present findings in basic science, clinical medicine, and public health.

Allison E. Aiello, PhD ’03, of the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center led a discussion examining the need to translate basic science insights from animal models to humans. The Columbia Aging Center’s Alan Cohen, PhD, said animal models are important but cautioned that mice with short lifespans are substantially different

from humans. CUIMC clinicians presented findings on disrupted sleep, which disproportionally affects older people. Representatives from neurology, nursing, pulmonology, and cardiology also shared findings. Columbia Mailman’s Thalia Porteny, PhD, spoke to the effect that social determinants of health have on aging, while Katherine Keyes, PhD ’06, MPH ’10, pointed to spikes in suicide and binge drinking among older adults.

Daniel Belsky, PhD—a co-lead on the symposium planning committee with Gregory Alexander, PhD, RN, of Nursing, and Caitlin Hawke, associate director of programming at the Columbia Aging Center—added that scientists need to both “translate up from the basic sciences, but also translate back down,” to make sure mechanisms identified in the lab are present in communities of people.

Katrina Armstrong, CEO of CUIMC, concluded the plenary by announcing that CHAI would immediately launch $240,000 in pilot funds to foster new collaborations. “I feel a sense of optimism coming from the people in this room, but also an incredible sense of urgency,” she said. “We need to get this work done.”

HEATHER KRASNA, PhD, EdM, ASSOCIATE DEAN OF CAREER SERVICES, TOOK A CLOSE LOOK AT SALARY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PUBLIC- AND PRIVATE-SECTOR JOBS AND PUBLISHED RESULTS IN THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Thirty of 44 occupations paid at least 5 percent less in government than the private sector, with 10 occupations paying 20 percent to 46.9 percent less. To develop a sustainable public health workforce, health departments must consider adjusting salary or using creative incentives such as student loan repayment for hard-to-fill roles.

A NEW INITIATIVE AT COLUMBIA MAILMAN SCHOOL WILL INVEST IN PUBLIC HEALTH SOLUTIONS FOR THE SURGING MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS—for example, examining how changes to the physical and social environment affect mental health. Called SPIRIT (Social Psychiatry: Innovation in Research, Implementation, and Training) and led by Katherine Keyes, PhD ’06, MPH ’10, the effort will explore the root causes of the rise of mental health problems, including social determinants of health. Fifty participating faculty come from across Columbia University Irving Medical Center and explore factors giving rise to mental illness, such as the emotional stress of climate change, social media and other new technologies, as well as what is driving poor outcomes in populations like Black and LGBTQ+ communities.

Other efforts will examine how brain development, stress response, and loneliness each play a role. Researchers will also examine possible solutions. These include school- and community-based prevention programs, economic and social policy, crisis support, and stigma reduction. SPIRIT also offers pilot funding and mentoring to scholars to further expand the research and keep the scholarship and collaboration going long term.

The Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health welcomes a new department head this fall. Thoai D. Ngo, PhD, MHS, is an internationally recognized scientist working at the intersections of global public health, population dynamics, gender equality, and sustainable development. He comes to the School from the Population Council, where as vice president for social and behavioral science research he led a global team of interdisciplinary scientists with expertise in climate science, demography, epidemiology, economics, public health, and sociology. Before that, Ngo was the vice president and senior director of research at Innovation for Poverty Action, directing a team of 500 research staff in conducting over 250 impact evaluations of programs and policies to address global poverty in 18 countries.

Ngo is also the founding director of the Girl Innovation, Research and Learning (GIRL) Center, a globally recognized hub for research on adolescents. He received a PhD in epidemiology and population health from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and his Master of Health Science in global epidemiology and disease control from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

AS THE CLIMATE WARMS, SWATHS OF PERMAFROST ARE THAWING. ARCTIC PERMAFROST STRETCHES ACROSS Alaska, Scandinavia, Russia, Iceland, and Canada and is a reservoir of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. With little known about these potentially infectious agents, the School’s Center for Infection and Immunity (CII) was invited to visit Fort Wainwright, Alaska, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility. J. Kenneth Wickiser, PhD, the administrative director of the Global Alliance for Preventing Pandemics (GAPP) at CII, was one of a handful of civilians present as advisors in February when Army Corps of Engineers members extracted samples for research to detect pathogens in permafrost. “Melting of permafrost will trigger the release of pathogens not seen for thousands and thousands of years,” says Wickiser, an associate professor of Population and Family Health. “Most of our work out of CII and GAPP is in temperate or tropical climates. But we will be working in other climates, and these are the places likeliest to be subject to climate change. A significant number of people are living on top of or exposed to permafrost.”

Researchers inside the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permafrost tunnel, which is held at around 25° F, prepare to take samples.

The Army Corps of Engineers will send ice core and permafrost samples to CII to assess for viral and bacterial pathogens, and CII will direct further sampling from areas where there is currently no melting but where permafrost is expected to melt in the future. “The goal is to get ahead of this,” says Wickiser, and tests invented at CII, VirCapSeq-VERT and BacCapSeq, will enable CII to do so. “The tools we have here are great in that they assess all pathogens simultaneously. So you don’t have to know exactly what you are looking for to find it.”

The same innovative tests are also helping CII interrogate wastewater at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Like permafrost, wastewater can contain a massive biological load, and looking for harmful pathogens can be like seeking a needle in a haystack. But CII’s tests enable the noninvasive detection of pathogens circulating in a community of hundreds of students housed in close quarters. “COVID-19, measles, mpox, adenovirus ... our technology finds everything all at once,” says Wickiser. With new uses for CII’s tests arising frequently, there is seemingly no end to the potential for these breakthrough technologies.

TWO STUDIES BY ROBBIE M. PARKS, PhD, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH SCIENCES, POINT TO HOW CLIMATE CHANGE MAY WORSEN HEALTH EFFECTS DUE TO HEAT EXPOSURE. Parks and fellow researchers found that temperature spikes due to climate change led to a marked increase in the number of hospital visits for alcohol-related disorders, including alcohol poisoning, alcohol-induced sleep disorders, and alcohol withdrawal in New York state. The higher the temperature, the more hospital visits. Higher temperatures also resulted in more hospital visits for disorders related to cannabis, cocaine, opioids, and sedatives, but only up to a

point—possibly because above a certain temperature people are less likely to go outside. The findings could inform policy on proactive assistance of alcoholand substance-vulnerable communities during periods of elevated temperatures, which stand to become increasingly common due to climate change.

In a separate study, Parks and fellow researchers also determined that an estimated 1.8 million incarcerated people in the United States—primarily in Florida and Texas—are exposed to a dangerous combination of heat and humidity, on average experiencing 100 days of such conditions each year. In recent decades, the number of

dangerous humid heat days in carceral facilities has increased, with those in the South experiencing the most rapid warming. (The Starr County Jail in Rio Grande City, Texas, averaged 126 days of dangerous humid heat per year.) Exposure can lead to heat stroke and kidney disease from chronic dehydration, among other health issues. “Dangerous heat impacting incarcerated people has been largely ignored, in part due to perceptions that their physical suffering is justified,” says Parks. “Laws mandating safe temperature ranges could mitigate the problem.” Forty-four states do not require air conditioning for inmates.

OpenAI’s GPT-4 can accurately interpret types of cells important for the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing with high consistency equivalent to the performance of human experts doing time-consuming manual annotation, Biostatistics researchers reported in Nature Methods.

The researchers assessed GPT-4’s performance across 10 datasets covering five species and hundreds of tissue and cell types, including both normal and cancer samples. GPT-4 matched manual analyses in more than 75 percent of cell types in most studies and was notably faster.

“The process of manually annotating cell types for single cells can take weeks to months,” says study author Wenpin Hou, PhD, assistant professor of Biostatistics. “GPT-4 can transition the process from manual to a semior even fully automated procedure and be cost-efficient and seamless.” The researchers have developed GPTCelltype software to facilitate the automated annotation of cell types using GPT-4. While GPT-4 surpasses current methods, there are limitations. “But fine-tuning GPT-4 could further improve performance,” Hou says.

AMERICANS LIVING IN PUBLIC HOUSING SUPPORTED BY THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (HUD) have significantly lower blood lead levels than comparable populations, likely due to tighter enforcement of residential lead paint laws in HUD buildings, reports a new Columbia Mailman School study.

HUD provides affordable housing assistance to nearly 5 million families. The new study is the first to examine blood lead levels (BLLs) by federal housing assistance status. People with HUD assistance had 11.4 percent lower blood lead levels than a comparable waitlist group. They also had 40 percent lower odds of having a risky BLL. No protective effect was seen for housing choice vouchers. (HUD enforces more stringent lead controls in public housing units versus voucher-eligible units.) The link between housing assistance and BLLs was weaker for non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American participants than for non-Hispanic Whites, possibly due to exposure to other lead sources, such as contaminated drinking water and pollution.

“Lead exposure is a major health risk at any level,” says senior author Ami Zota, ScD, associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences. Elevated BLLs in adults are linked with high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and kidney problems. Even low levels of exposure among children have been associated with neurocognitive impairment, poor school performance, behavioral problems, and criminality later in life. Approximately 3 million children currently live in public housing.

24% 35% 53%

INCREASE IN NUMBER OF FULL-TIME FACULTY SINCE 2014

PROPORTION OF FULL-TIME FACULTY WHO ARE PEOPLE OF COLOR, A HISTORIC HIGH

PERCENTAGE OF TENURED FACULTY WHO ARE WOMEN

Reducing Cancer Risk Residing in a more walkable neighborhood protects against obesity-related cancers in women, report researchers in Epidemiology. They studied 14,274 women for more than 20 years and found that those in neighborhoods with higher walkability levels, as measured by average destination accessibility and population density, had a lower risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Moderate protective associations were also found for endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, and multiple myeloma. 28% EIGHT 25

People with cognitively stimulating occupations between ages 30 and 70 had a lower risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia after age 70, finds a new study reported in Neurology The study is the first to connect cognitively stimulating occupations and reduced risk for MCI and dementia with objective assessments rather than subjective evaluations.

The researchers looked at occupations such as teacher, salesperson, nurse and caregiver, office cleaner, civil engineer, and mechanic. The group with low occupational cognitive demands had a 37 percent higher risk of dementia compared to the group with high occupational cognitive demands. “Our study highlights the importance of mentally challenging job tasks to maintain cognitive functioning,” says Vegard Skirbekk, PhD, former professor in the Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health and the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center, who initiated the project. The next step will be to pinpoint the specific occupational cognitive demands that are most advantageous for healthy aging.

Researchers at Columbia Mailman School and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene have found that a stunning 30 percent of New York City residents experience energy insecurity, meaning they are unable to pay household energy bills, are in debt due to energy bills, have received a shutoff notice, or have shown other signs they are unable to meet their household energy needs due to cost. Residents with indicators of energy insecurity had higher odds of respiratory, mental health, and cardiovascular conditions and electric medical device dependence than residents with no indicators, the researchers reported in Health Affairs.

More than 1 in 4 New York City residents experienced indoor temperatures that were too cold (30 percent) or too hot (28 percent). Twenty-one percent had difficulty paying utility bills. Of those, a majority were in debt for energy costs. Three percent of residents experienced service shutoffs for heat, electricity, or gas. Black non-Latino and Latino residents, renters, recent immigrants, and households with children all experienced significantly higher levels of energy insecurity than their counterparts, notes study senior author Diana Hernández, PhD, associate professor of Sociomedical Sciences.

OLDER ADULTS WITH ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) HAVE A HIGHER CAR CRASH RISK THAN OTHER OLDER ADULTS, finds a study that tracked more than 2,800 drivers aged 65 to 79 with in-vehicle devices for more than three years. The researchers linked ADHD to a 74 percent increased risk of crashes, a 102 percent increased risk in self-reported traffic tickets, and a 7 percent increase in the risk of hard braking events.

About 8 percent of adults are known to have ADHD. “ADHD could affect driving safety in different ways,” says Guohua Li, MD, DrPH, professor of Epidemiology. Inattention might result in a driver failing to notice a vehicle coming from the side, while impulsive tendencies could lead to speeding or cause a driver to cut in when it might be safer not to do so. Enhanced screening, diagnosis, and clinical management of ADHD in older adults might help counter driving issues, as could limiting use of in-vehicle media, such as the ability to make phone calls while driving.

96% 66 24%

NUMBER OF COUNTRIES REPRESENTED IN STUDENT BODY

LIKELIHOOD A GRADUATE IS EMPLOYED OR CONTINUING THEIR EDUCATION WITHIN SIX MONTHS OF GRADUATION

PROPORTION OF STUDENTS WHO ARE UNDERREPRESENTED MINORITIES

report that the average liter of bottled water contains 240,000 detectable plastic fragments—a far greater number than previous estimates.

MAKING POLICE THE PRIMARY SOLUTION FOR INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE (IPV) MAY HARM SURVIVORS, according to a new study that is the first to review the consequences of IPV policing in the U.S. IPV, which includes physical and sexual violence, psychological abuse, and other forms of coercion between current or former partners, impacts more than 40 percent of people in the U.S. The country has long maintained a police-centric response to IPV, despite growing calls for reform; there is mixed evidence that arrest reduces subsequent victimization and studies have documented an association between mandatory arrest laws and risk of survivor arrest.

The researchers analyzed scholarly articles about IPV published over 40 years. “More research is needed, but we know the current approach is ineffective and damaging,” says Seth Prins, PhD ’16, assistant professor of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences. The study noted greater negative effects for Black survivors, as well as a lack of research into some consequences of IPV policing, such as police violence against survivors, reduced help-seeking, survivor arrest, or child protective services involvement.

There is a growing unmet need for treatment for cannabis use disorder (CUD), yet treatment has actually decreased since 2004, particularly in states with medical cannabis dispensaries. “We found that specialty treatment for cannabis use disorder remained very low and decreased in states with dispensary provisions, even among people reporting pastyear CUD, which is an indicator of treatment need,” says Pia Mauro, PhD, assistant professor of Epidemiology. CUD has negative health and social consequences yet there are no pharmacological treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration. While cannabis use in the U.S. remains illegal at the federal level, 38 states and the District of Columbia have medical cannabis laws, and 24 states and the district have recreational cannabis laws. “Few people needing CUD treatment in our study perceived a need for treatment,” Mauro observes. In other studies, cannabis laws have been associated with lower cannabis-related perceived harms.

“We urgently need to target efforts in support of people with CUD, particularly in states with dispensaries. This includes training providers to increase screening and discussions about cannabis use,” says Mauro.

500+ 18% 419

PROPORTION OF STUDENTS WHO ARE FIRST-GENERATION COLLEGE GRADS

NUMBER OF CAREER COUNSELING APPOINTMENTS WITH ALUMNI COMPLETED BY THE OFFICE OF CAREER SERVICES LAST YEAR

NUMBER OF CLASSES OFFERED DURING THE 2023–2024 ACADEMIC YEAR

Dean Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, has led Columbia Mailman School of Public Health to become one of the world’s top institutions for public health education and science. Through 16 years, thousands of students, and one global pandemic, her leadership has ensured that students go out into the world prepared to innovate and take charge to address society’s most persistent and urgent public health challenges. As she prepares to step down at the end of the 2024–2025 school year, Fried talks with alumna and Board of Advisors member Perri Peltz, MPH ’84, about what’s needed and what’s next for public health.

Thank you, Dean Linda Fried, for your visionary leadership. Take us back to when you started. How did you see this school then?

The school that I had the privilege to join 16 years ago had amazing people and was ready to rise to a whole new level. There was deep commitment to the public and the public good, and enough expertise to cover the leading edge of so many issues. My role has been in part to better support people’s success, to ensure the School has the institutional goals and capabilities and the bench staff to tackle the very complex issues that we were intent on tackling.

As somebody who had experience with the School back in 1984 when I was a master’s student and then when I returned as a doctoral student, I’ve seen the evolution. How did you take on the enormity of what you have been able to accomplish?

I was excited to come to an institution of such deep commitment and to lead in building the fabric of an institution that could support its mission: to bring scientific knowledge to the problems that threaten people’s health. And then to build the science, to understand how to keep people healthy. That commitment was there.

My approach to leadership is to help enable an institution to be great. It requires building the substance from the bottom up rather than the image from the top down, so that you can actually deliver on what the future needs.

When I met you, Linda, maybe 15 years ago. I remember thinking that you were looking at this school in a very big way. You spoke about systems. You used the word interdisciplinary. What were you thinking, and have you accomplished that?

It was clear to me that the challenges of the 21st Century are ones where no one discipline is sufficient to understand them or to solve them. The causes are complex and multifactorial. Let’s take really any health problem, whether it’s what causes a pandemic or what causes people to develop heart disease or stroke. Science has unveiled that there are many factors that have to come together in a perfect storm to end up with those outcomes, and you need multiple disciplines to understand the truth.

It’s never one thing that causes ill health, and it’s never one thing that creates health. You need to have multiple disciplines working together from different points of expertise to say, well, how do we solve this effectively? In 2008, it was clear to me that there was no academic institution that had yet taken those learnings about the necessity of interdisciplinary thinking and intentionally built the range of sciences needed to solve these challenges effectively. We had to figure that out. And we had to transform from very strong disciplinary expertise—not scuttle that, not throw it out, but expand capabilities—and unite disciplines to solve complex problems. My 16 years here has been dedicated to laying that foundation; to have successful interdisciplinary science be the norm. The great news is we have accomplished it.

When I walked out of that meeting, I thought to myself, doesn’t she know that academia doesn’t do this? Honestly, I didn’t think that there was a chance that you could accomplish what you were talking about. Of course, at the time, I didn’t know you. How is this school different now?

It looks very different. That’s not all due to me. It is due to our ability to come together as an institution and ask: What will the future demand of a great school of public health, a great science institution, an educational institution, committed to building a better future of health? We interrogated that together and came to a shared agreement that interdisciplinary science and knowledge had to be at the core. That has required many levels of change. Over a number of years, we went through formal processes to identify the issues that we should confront that are threatening our health and decide whether they required interdisciplinary solutions, scientifically and educationally.

Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, becomes dean of the School. A national leader in the field of geriatric health and epidemiology, she is the first woman in the position.

The Biostatistics Epidemiology Summer Training Diversity Program (BEST) for students from underrepresented backgrounds begins. In subsequent years, it is joined by other “pathway” programs to bring historically marginalized groups into the public health field.

A strategic planning process identifies critical issues for public health in the 21st century.

Dean Fried is instrumental in launching Columbia University’s first global center in Europe.

Professors Quarraisha Abdool Karim, MS ’88, PhD, and Salim S. Abdool Karim, MS ’88, MD, PhD, publish a study in the journal Science finding that tenofovir gel is effective in preventing HIV transmission in women.

The School establishes the Climate and Health Program.

The revamped MPH Core Curriculum debuts, providing a rigorous program of interdisciplinary training in public health science and leadership. The Center for Injury Science and Prevention, a CDC-funded Injury Control Research Center, is founded.

Columbia Mailman School and the Columbia Journalism School take responsibility for leading Age Boom Academy, a summer boot camp for journalists on aging issues.

The University creates the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center, an endowed, universitywide, interdisciplinary research and policy center housed within the School.

Sidney and Helaine Lerner establish the Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion and corresponding endowed professorship in public health promotion.

The Incarceration and Public Health Action Network is developed to examine mass incarceration through a public health lens and incorporate criminal justice reform into public health education.

The Master of Healthcare Administration (MHA), offered through the Department of Health Policy and Management, gives students intensive training in leadership and management along with a broad introduction to public health, health policy, and healthcare systems.

ICAP at Columbia begins providing technical assistance for the Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (PHIA) Project to capture the state of the epidemic in the most affected countries.

President Barack Obama cites the School’s research at a White House meeting to shine a light on the link between climate and health.

The first cohort of Tow Scholars is announced. Supported by the Tow Foundation, the program fosters research by mid-career faculty.

Researchers at the School’s Center for Infection and Immunity (CII) report that chronic fatigue syndrome is a physical illness, rather than a psychological disorder.

The Symposium on Preventing Childhood Obesity brings together researchers across disciplines.

An international roster of experts gathers in Shanghai to address aging in China and around the world at the Columbia-Fudan Global Summit on Aging and Health.

Fried receives the Inserm International Prize, a scientific award given each year by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, the French equivalent of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

The Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education (GCCHE), a network of health professions schools and programs, launches.

The School partners with Barnard College to offer a 4+1 program that allows undergraduates to earn an MPH a year after they graduate with a BA. Similar programs follow with other schools.

David Rosner, PhD, MPH, and Gerald Markowitz, PhD, give testimony in a landmark case in which paint manufacturers are found responsible for lead contamination in California. Toxic Docs, a repository of documents related to toxic exposures, launches.

The Yusuf Hamied Fellowship Program, supported by the celebrated Indian scientist and pioneering business leader, catalyzes collaborations between researchers at Columbia Mailman School and their counterparts in India.

Experts from across the School pioneer testing techniques and therapies for COVID-19, conduct modeling to forecast spread, and offer technical assistance worldwide. Faculty and students support community awareness and vaccine programs.

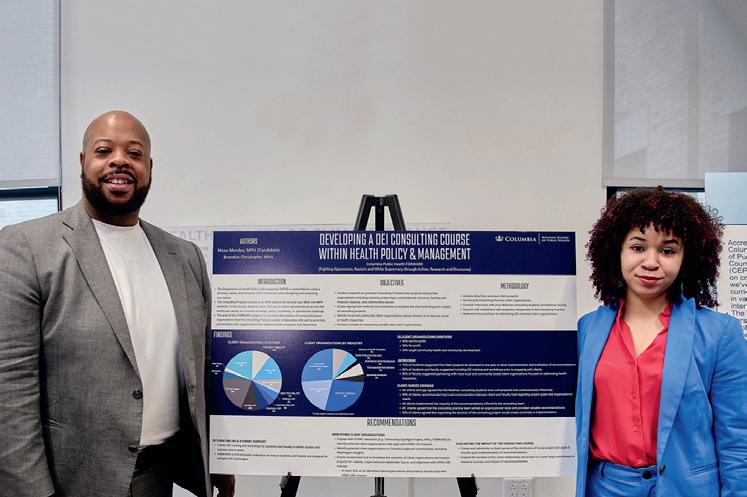

Students, faculty, and staff create the FORWARD (Fighting Oppression, Racism and White Supremacy through Action, Research and Discourse) initiative, one in a series of efforts to promote inclusive and equitable education in the field of public health..

Here’s a key example. In 2008, climate change and its effects on health rose in our analysis to one of the top issues that will threaten health in this century. We know that climate change is causing extremes of heat, changes in hurricanes, flooding, drought, a whole set of natural disasters, wildfires. It’s causing food insecurity and water insecurity. And all of those are threatening human health and threatening human survival and creating, in many parts of the world, refugees. And I didn’t even mention the rise in infectious diseases in areas that never saw them before, like malaria, because of a warming climate. There is no one discipline that can address all those consequences. All of these require teams of people handling these different problems.

Working together as teams, we went on to build the governance to support interdisciplinary work. Will faculty be promoted for interdisciplinary work? Will they have interdisciplinary centers to work in that will bring these teams together? We’ve built the governance to support success in interdisciplinary science. We have recruited 130 new faculty in my time as dean, in large part to bring the expertise to tackle the issues of our collective future.

In your letter to the School community sharing that you would be concluding your service as dean, you write, “We have accomplished so much together, but our ambitious community knows there is more to be done.” What is on the horizon?

Public health was responsible for adding 25 of our increased 30 years of life expectancy over the last century. Now, public health needs to take the lead in ensuring those additional years are healthy. There is an opportunity for the United States to invest in a new vision of public health focused on healthy longevity for everyone. There are many dimensions where public health needs to rise and to redefine the role of the public health system, so as to deliver conditions that enable people in every community in this country to be healthy. And there are many other challenges. Why are cancers rising in young people? How do we eliminate the number four cause of death around the world, which is air pollution? Health is a human right. Public health has shown that prevention works. And it is public health’s responsibility to deliver the vast majority of health to the public.

Is there anything else that keeps you up at night in terms of public health?

The threat of loneliness is a huge threat. It is a consequence of many forces which are new to human beings, like social media, disinformation and misinformation, the pandemic exacerbating disconnection from other human beings. Young people and old people, especially, feel isolated and lonely. And then on top of that, loneliness is shredding our ability to come together to solve issues that we can only solve together. If we want to solve loneliness, by definition, we need to do it together.

Drug addiction and substance use are other issues where we need collective action, both to care for people who are addicted, but also to tackle the factors that are driving people to addiction. No one approach can solve this alone.

As you are talking about things that have kept you up at night, I recall that at some of the deepest, darkest moments—the COVID-19 pandemic being one—you have seemed calm. You said to me at the time that this had to do with your deep faith in the School and your love of the School. What is it that you love about it?

I love walking in the door every morning. I am surrounded by people who are committed to creating knowledge as a basis for a better world and empowering all sectors of society to accomplish that. It’s inspiring to be surrounded by people who are committed to the public good; who are spending their lives dedicated to improving well-being and elevating human society. How can that not be inspiring?

When I talk to people on your staff about what makes you such an incredible leader, it’s not related to public health specifically; it’s leadership skills. You have been a student of leadership. What have you learned?

MY COLLEAGUES AND I HAVE BEEN ABOUT CHANGE FOR THE GOOD SINCE I’VE BEEN AT THE SCHOOL, AND WE HAVE ACCOMPLISHED TRANSFORMATION TOGETHER.

I was persuaded to study leadership out of necessity many years ago. I observed that principled and effective leadership matters. I was confronted by the need to see if there was a skill set I could learn because I’m a physician, I’m a scientist, but neither of those calling cards come with training in leadership skills.

What I’ve learned over the years is that there is a whole set of skills that can be applied at any stage of leadership, and that some of what you need to do is to create a vision of what the future demands—that is aspirational, and that, hopefully, will unite people and inspire them to work together. And then it’s your responsibility as a leader to make that aspiration clear and to make it achievable and to make every person feel they can be part of it, and they won’t fall off the boat that’s going there.

What is next for Dean Linda Fried?

Well, I understand I’ve earned a sabbatical, which I will take. But I’m excited to come back to the faculty and continue to lead the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center, a university-wide center dedicated to the idea that we can create a third demographic dividend, where societies and people flourish because of longevity, not despite it.

What wonderful news that you will be returning. Linda, as we conclude is there one message that you would like to share with the Columbia community?

I’ll give you two. One is that change is more than possible. People say that longstanding institutions cannot change. And particularly that universities don’t change. I very proudly can say that my colleagues and I have been about change for the good since I’ve been at the School, and we have accomplished transformation together.

The other message is something I am obsessed with, which is that public health is an exemplar of public goods. For capitalism to survive there are essential components that we must make sure are strong because everyone gains from them and no one profits from them. Public health requires collective investment to prevent disease, disability, and injury—which accounts for seventy percent of our overall health. And when we make adequate investment in public health at the science level, at the practice and policy level, all people have the opportunity to flourish and all sectors of society do better.

We’re going to end with a Linda Fried Fun Fact. I have learned that you have a black belt in Aikido. Has that training informed the way in which you work?

I trained in Aikido for many years; it’s deeply part of who I am. Aikido is a nonviolent Japanese self-defense art in which you learn that you don’t have to be big and muscular to lead. You can lead change, if attacked, by joining with the attacker and redirecting aggression toward a shared end while protecting the attacker from getting hurt. It’s possible to do that in almost any situation, to turn situations of conflict to better ends and mutual benefit. And that is the foundation of how I think about leadership.

The School hosts the inaugural Data Science for Public Health Summit, convening public health leaders to consider the many dimensions of data science in public health.

Faculty, with researchers across the University, launch the Columbia Scientific Union for the Reduction of Gun Violence (SURGE).

A team led by Dean Fried synthesizes evidence on the aging-related pathophysiology underpinning the clinical presentation of frailty. The findings appear in the inaugural issue of the journal Nature Aging

CII launches the Global Alliance for Preventing Pandemics (GAPP) to establish sustainable infrastructure for infectious disease discovery, surveillance, diagnostics, and response through global capacity building.

As the School celebrates its centennial, Dean Fried leads a visioning exercise to chart a course for the coming decades.

Dean Fried co-chairs a commission that publishes the National Academy of Medicine Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity.

Dean Fried receives the Insignia of the Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest order of merit, recognizing her positive impact on France and on a global level.

The School announces the recipients of eight Dean’s Centennial Grand Challenges grants for interdisciplinary research projects that address some of the 21st century’s biggest public health challenges.

The Food Systems and Public Health certificate program launches to train students in the role that food plays in public health.

Columbia Mailman ranks third in the nation for NIH Prime Awards to schools of public health, with a gain of 61 percent since 2018.

The School co-organizes the inaugural Global First Ladies Academy, hosting eight first ladies from African nations and U.S. first lady Dr. Jill Biden.

The Columbia Mailman Center for Innovative Exposomics launches to bring sophisticated environmental analysis to open new avenues for prevention and treatments.

Professor Katherine Keyes, PhD ’06, MPH ’10, leads the newly created SPIRIT (Social Psychiatry: Innovation in Research, Implementation, and Training) initiative to catalyze collaboration to address the mental health crisis.

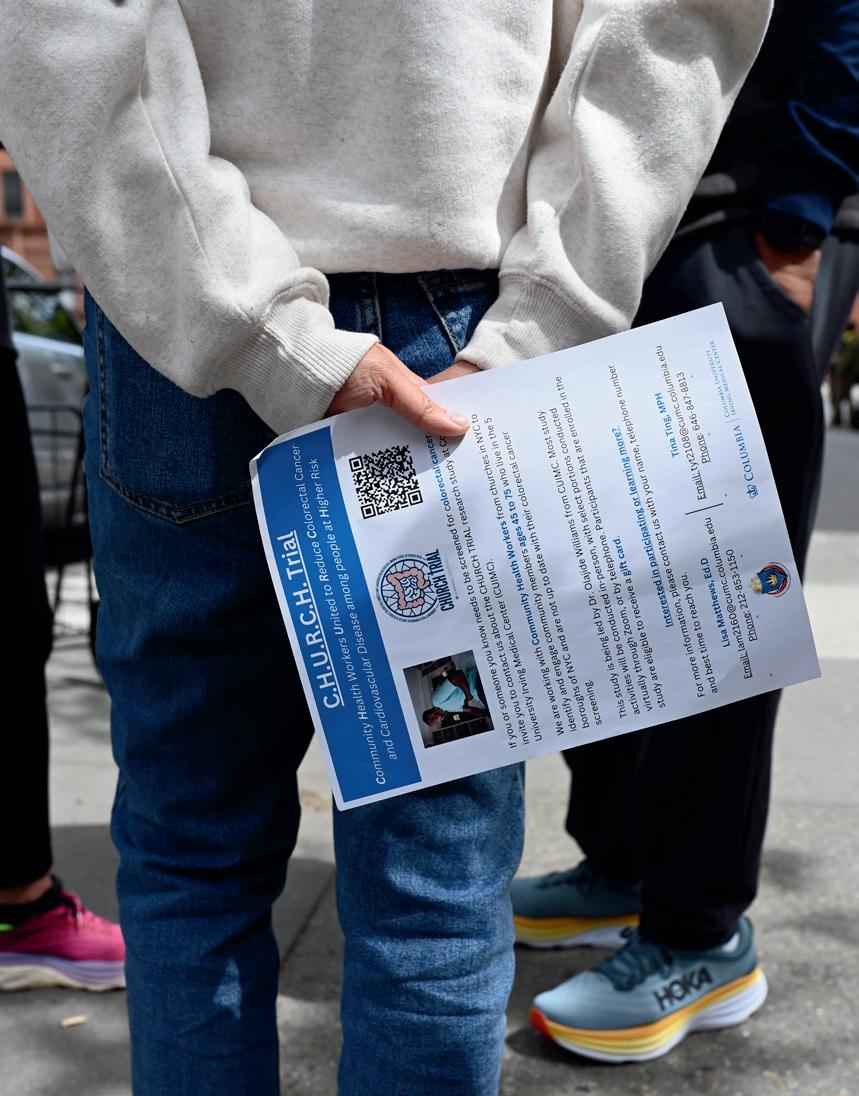

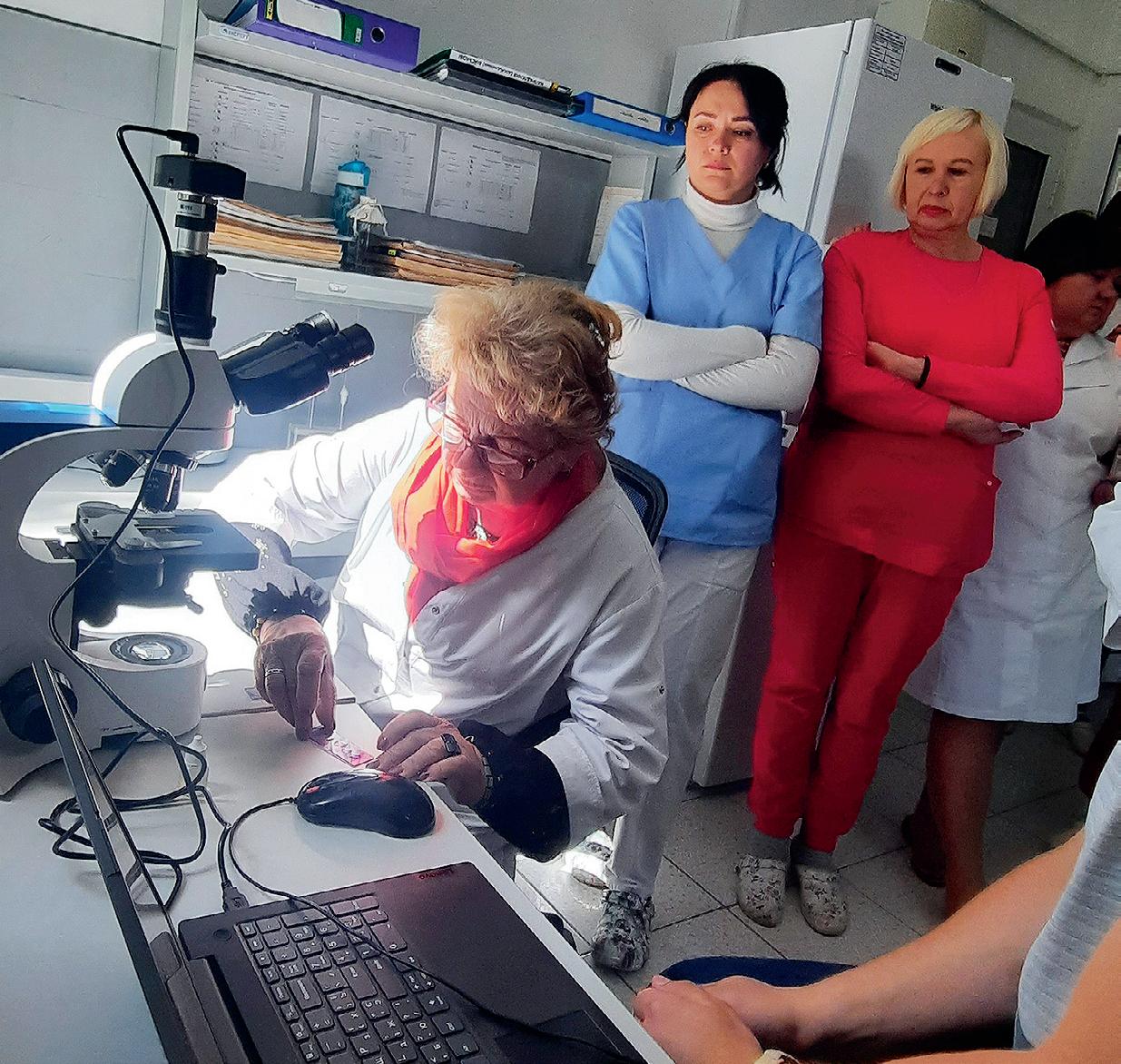

SCENES IN THE CITY From top left: Student Hersh Pareek, MPH ’25, doing outreach for the CHURCH study in Harlem; Bermarys Santos Pimentel examines her family’s air purifier in the Bronx; ICAP outreach assistant Ramiah Fennell; students Sarahy Martinez, MPH ’25, and Lilly Krupp, MPH ’25, at God’s Love We Deliver; Harlem community member Ilean Taylor and student Tobechi Dimkpa ’25, at Convent Avenue Baptist Church; South Bronx Unite is the School’s partner on air pollution research; the ICAP mobile van in the community; Nicole Bayne, MPH ’21, project manager, and Sukhmani Kaur, MPH ’24, research assistant, work on indoor air quality research; Convent Avenue Baptist Church Deaconess Marie Taylor, a CHURCH trial outreach volunteer; Markus Hilpert, PhD, leads air pollution research; a flyer for the CHURCH trial; Kaur and Bayne with Marileidy Pimentel at her home; Mychal Johnson, cofounder of South Bronx Unite; tobacco ads in Harlem have been a focus of research by Sociomedical Sciences Assistant Professor Daniel P. Giovenco, PhD, MPH

Faculty, staff, and students from Columbia Mailman School are working with New York City neighborhood residents to shed new

light on persistent public health challenges.

By Dana Points

COLUMBIA MAILMAN SCHOOL ALREADY HAD A CENTURY-LONG HISTORY OF DEVELOPING RESEARCH PARTNERSHIPS, facilitating student practica, and collaborating to improve public health in Northern Manhattan. Then COVID-19 hit. When the School’s leaders saw how longstanding health inequities fueled the pandemic’s devastating effect on the neighborhood, they knew they had to do more. And so, in 2021, under the guidance of Dean Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, the School began to lay the groundwork for a Community Health Equity Collaborative (CHEC), launched in 2024, that would build new academic-community partnerships, accelerating efforts to decrease health inequities and improving the health of neighboring communities. Today, Columbia Mailman School is doing more than ever to reach out to those who live in the community and to its churches, nonprofit organizations, religious institutions, and advocacy groups.

In the field of public health, two or three decades ago, the norm was that experts communicated to the public when there was certainty. “That model said, ‘I don’t want to create stress about health risks, particularly environmental ones, until I know there is sufficient data,’” says Mary Beth Terry, PhD ’99, a professor of Epidemiology and Environmental Health Sciences

who has been at Columbia Mailman School for 25 years, first as a PhD student and then as a faculty member.

Today, community organizations are increasingly partners from the ground up. “Ideas are first discussed with community advisory boards to get their input on whether a project is worthwhile,” says Terry. “The ‘deficit’ model of communication has been replaced with a ‘dialogue’ model. The deficit model is linear. The dialog model is a circle: You still have scientists with disciplinary expertise, but you also have community members who have their own expertise, and policymakers. And we acknowledge that science evolves constantly so we have to communicate on an ongoing basis.”

You can see that circle in action in a collaborative effort underway between the School’s scientists and activists in

laboration that used monitors to document traffic related to the opening of a grocery warehouse. “We were able to highlight the environmental impacts of the new facility on the community,” says Markus Hilpert, PhD, associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences and one of the project’s leads. The findings were published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated to community members through outreach events. The research has helped South Bronx Unite fight land use and transportation policies that would increase traffic in the community.

The researchers’ latest effort, funded through the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, has more than tripled the number of sensors of the previous project, allowing for more detailed analyses as they measure, minute by minute, levels of particulate matter, carbon mon-

the South Bronx. The South Bronx experiences heavy truck traffic, and air pollution has had a devastating effect on the health of its residents, most of whom are low-income people of color. The area has one of the nation’s highest rates of asthma, with 1 in 4 children affected. The Mott Haven neighborhood is often referred to as “Asthma Alley.”

A research project organized by environmental justice group South Bronx Unite and environmental health scientists at Columbia Mailman School has installed 25 air pollution monitors in strategic locations throughout Mott Haven and nearby Port Morris, with a control monitor in the affluent, tree-filled western Bronx neighborhood of Riverdale, which has fewer industrial sources of particulate matter.

This research is driven by the community’s needs and designed to answer its questions. It is modeled on an earlier col-

oxide, ozone, and other substances. An anemometer, which measures wind speed, helps pinpoint air pollution sources.

Community-generated research ultimately cycles back to community organizations, which advocate for policy changes that foster health. Peer-reviewed research conducted with Columbia Mailman School scientists helped a coalition of advocacy groups co-led by South Bronx Unite to successfully lobby for New York state’s cumulative impacts law, which is designed to prevent the approval and reissuing of permits for actions that would increase inequitable pollution burdens on disadvantaged communities.

Terry is leading another air pollution research project in Washington Heights and the Bronx that is looking at indoor air quality. The team equipped families with HEPA air purifiers and measured inflammatory biomarkers for chronic disease.

They also provided the families with “green” cleaning products and an educational video about environmental and lifestyle risk factors and chronic disease risk reduction strategies. Families such as Marileidy Pimentel, Juan Santos, and their daughter Bermarys, who live in the Bronx, aren’t in the dark as study participants—they’ve been asked for their feedback as the project has unfolded. “Despite 30 years of research, chronic diseases were not reduced across all groups,” says Terry. “So our old model of communicating with communities didn’t work. Now this idea of having community involvement in lots of projects versus only special projects is becoming the norm. The National Cancer Institute now requires scientists to understand what is relevant to the community and how to have an ongoing dissemination of information related to the cancer burden there. And funders increasingly emphasize how the work being done reduces health disparities, versus only reducing disease risk.”

Connecting with the community includes forging partnerships with nonprofits that have deep roots in specific populations. Nour Makarem, PhD, assistant professor of Epidemiology, is leading a first-of-its-kind Food Is Medicine clinical trial in New York City in partnership with the nonprofit God’s Love We Deliver (GLWD). The trial began enrolling participants in August, with a focus on recruiting in Harlem and Washington Heights. A conversation between Makarem and Kelly V. Naranjo, MS, manager of research and evaluation at GLWD, was the impetus for the project and other nonprofits have since signed on.

The study’s goal is to help determine how to enhance the effectiveness of medically tailored meals (provided by GLWD) among people who have multiple risk factors for heart disease, such as Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Among those with more severe disease, who qualify for medically tailored meals, the research is examining whether

supplementing meal delivery with a culturally relevant heart health curriculum will result in improved diet quality and better blood sugar and blood pressure metrics. “We have joined with Ryan Health, a community healthcare provider, and partnered with the nonprofit Harvest Home Farmer’s Market to implement community-centered nutrition education, including cooking demonstrations and fresh produce bags,” Makarem says. Among a second group of people who have less severe disease and don’t currently qualify for meals, the study is examining whether introducing the special meals earlier in the course of disease might forestall problems and, if so, what “dose” of meals is most impactful and cost effective. The American Heart Association is funding the research.

“A really big piece of community-engaged research is having your finger on the pulse of what is important to people, what works, and what doesn’t,” says Makarem. Students involved in the study are learning this firsthand. They began volunteering with GLWD in the weeks leading up to the study and engaging with the communities they would be recruiting from by screening for diabetes and high blood pressure at neighborhood health fairs. Now, they are recruiting patients and administering questionnaires to the 200 residents who will participate in the study, scheduling them for program appointments, and keeping them engaged for eight months.

Along the way, students get a firm understanding of community-engaged and community-led research, and the hurdles that researchers face. “The students are great at working with participants in different neighborhoods, from different backgrounds. They are learning how to implement contextual interventions and how we are in ongoing conversation with the community as the study progresses,” Makarem says.

The Food Is Medicine study is hardly the only current research that engages students with community members. The

CHURCH trial (CHURCH stands for Community Health workers United to Reduce Colorectal cancer and cardiovascular disease among people at Higher risk) focuses on colorectal cancer awareness in collaboration with Black churches in Harlem and the Bronx. It is a National Institutes of Health–funded research study based at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. CHURCH partners with community health workers from the churches to engage New York City residents aged 45 and older who are not up to date with colorectal cancer screening. It’s just one of the projects spearheaded by the Columbia Center for Community Health, which is co-led by Robert E. Fullilove, EdD, associate dean for community and minority affairs and professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sci-

MPH ’25—to recruit study participants. Kim has found community-based research to be a valuable learning opportunity. “Sometimes in an academic environment you fall into being told things.You learn about a health issue, but hardly do you experience or talk to people dealing directly with it. Being part of community-based research has been meaningful in that regard. I learn in class, but then I see something out in the community, and I can connect the two.”

Much of the current research was already under way when, as a natural outgrowth of its work on health equity and justice,

ences at Columbia Mailman School, and Olajide A. Williams, MD, MS ’04, professor of Neurology and vice dean of community health at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

CHURCH draws many of its research assistants from Columbia Mailman School’s student population. “Working in the community is often interdisciplinary, cross-School, student-involved work, and it takes place in New York City— all things that make Columbia Mailman School a truly distinctive place to study,” notes Kathleen J. Sikkema, PhD, chair and Stephen Smith professor of Sociomedical Sciences. Valerie Kim, MPH ’25 (in center photo, above), joined as a research assistant earlier this year. She attends health fairs and church events, where she works alongside community members—and fellow students such as Tobechi Dimkpa, MPH ’25, and Hersh Pareek,

Columbia Mailman School announced that it was launching CHEC, housed in the Dean’s Office, with the goal of continuing and expanding innovative partnerships with Northern Manhattan communities to address complex underlying causes of health inequities and better improve health.

Faculty members Kelli Hall, PhD ’10, an associate professor of Population and Family Health, and Alwyn T. Cohall, MD, professor of Public Health and Pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Columbia Mailman School, led an extensive project to plan the new effort and identified more than 50 active community partnerships already run by departments, individual faculty members, administrative offices, and student groups. ICAP at Columbia was rolling through Harlem and the Bronx with a mobile clinic, evaluating whether using mobile health units to deliver

Air pollution is a focus of research and advocacy in the South Bronx.

integrated health services for people with opioid use disorder could improve HIV and substance use treatment and prevention. And for close to a decade, Daniel P. Giovenco, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor of Sociomedical Sciences, had been examining how minority communities are disproportionately targeted with ads for the deadliest tobacco products and looking at the link between tobacco use and neighborhood characteristics, such as tobacco retailer density, local tobacco control policies, and exposure to product advertising.

But while the breadth of the School’s partnerships was strong, “as meaningful as the School’s public health work has been to date, it has not been enough to fully offset the structural and societal issues that create disparities in the opportunity for health,” says Fried. “Addressing the underlying causes of health inequities in Upper Manhattan and the U.S. as a whole is a complex challenge that requires new solutions and partnerships between community, academic, and other organizations.” This School-wide centralization of CHEC within the Dean’s Office will ensure that collaboration with partners across departments and centers is coordinated to support outcomes.

CHEC is designed to be a true collaboration with the community, with neighborhood members receiving training on community-based participatory research (to enhance their capacity to collaborate with academic researchers) and community leaders helping the School’s faculty and staff to set goals and design service-learning projects for students that would foster learning in real-world settings. “This office is a lever we can use to dislodge health inequity and create conditions to foster health equity, while also creating a model of how academia can engage with the community respectfully,” says Ana Jimenez-Bautista, who was named executive director of CHEC in September and will fully assume her new role in 2025.

Successful public health interventions will likely require integration or consideration of many of the disciplines rep-

resented at Columbia University—from architecture to engineering to medicine. CHEC will provide the University with an umbrella for cross-discipline initiatives that can be guided by Columbia Mailman’s deep history and experience in New York City community engagement. The CHEC office will work with community members to jointly identify health priorities and the opportunities for successful intervention, with support of academic data science capabilities and implementation science. Three examples of interdisciplinary areas CHEC might focus on are trauma (which has a significant intergenerational impact on mental and physical health); support for formerly incarcerated individuals (including health support but also education, housing, and jobs); and neighborhood conditions such as pollution and food insecurity.

Jimenez-Bautista, who has worked in Northern Manhattan since 1989 and had roles at Columbia Mailman School for a decade, feels the time is right for the School to engage more deeply and cohesively with these long-standing challenges. “Thanks to Dr. Bob Fullilove and others like Dr. Williams, community-based participatory research has blossomed. We have talent and the interest from many of the faculty here in community-based research.” The School already has a 25-year history of partnership with WE ACT, the West Harlem environmental action coalition that has explored environmentally driven causes of poor health. But more can be done, and students are eager to participate. Says Jimenez-Bautista, “The students are coming in with more interest in prevention, in starting upstream of many of the health problems we are seeing, and engaging the common person in active participation. There are more robust student organizations at the School working on community engagement. I’ve seen a qualitative change since the pandemic—if you say, let’s talk about community, there are immediately ten students who raise their hand. That wasn’t always the case.”

Dana Points, the editor of this magazine, lives in Harlem.

A science storytelling class with Columbia Journalism School. A Health Policy and Management panel featuring the aide who spearheaded President Biden’s COVID-19 messaging. A contest to encourage creative communication strategies for public health professionals. These are just a few of the ways students and faculty are getting the word out about public health.

By Christina Hernandez Sherwood

Illustration by David Cooper

There is no denying it:

Today’s information landscape is punctuated by an increased mistrust of science, a partisan political climate, and a cacophony of social media voices. Public health experts must shout—strategically— in order to be heard.

This has led to expanded interest in a skill that Columbia Mailman School has long emphasized: public health communication—that is, the act of conveying public health information not only to peers, but also to society at large.

Public health professionals are realizing they need to change the way they think about this key skill. “Public health is largely invisible until there's a crisis. When the crisis recedes, the public health workforce fades into the background,” says Michael Sparer, JD, PhD, chair of Health Policy and Management. “We haven’t effectively communicated how public health makes life better for all of us, all of the time.”

Over the last year, faculty members have contributed to mainstream media outlets in growing numbers, publishing a host of articles and opinion pieces on a range of public health topics. The School’s public health professionals have long worked to effectively translate their research into practical lessons and health policy suggestions, Sparer says. But the onslaught of mis-

information surrounding the pandemic has amplified interest in communicating effectively. “More researchers are figuring out how to reach audiences that are not going to pick up the New England Journal of Medicine, but who might watch Fox News,” says Sparer. The School’s Communications office has seen a significant uptick in news articles and faculty op-eds published in top-tier mainstream outlets, notes Vanita Gowda, MPA, associate dean and chief communications officer. “Our School is a leading media source due in part to our educational focus on health communication. But our location in New York City—a media hub—and our faculty’s efforts to make public health knowledge and evidence as widely accessible as possible are also critical,” she says.

The interest in health communication also inspired a new class: When longtime friends Julie Herbstman, PhD, professor of Environmental Health Sciences and director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, and Duy Linh Tu, dean of academic affairs and professor of professional practice at Columbia Journalism School, shared a meal a few years ago, the conversation soon turned to work. While chatting about their respective challenges— Tu as a science journalist in a rapidly evolving field and Herbstman as a researcher trying to communicate her science without formal training in communication—they realized they could help each other. “There is a perception that scientists and journalists have an adversarial relationship,” Herbstman says. “It doesn’t need to be that way. We need each other, but we don’t work together very well.”

Spurred by (now former) Columbia University Provost Mary C. Boyce’s call for interdisciplinary course proposals, Herbstman and Tu, who met as undergraduates at Tufts University, began to develop a class that would, Herbstman says, “bridge the gap between scientific research and the distribution of important health information to the public.” The course, The Scientist and the Storyteller, demystifies public health research and journalism, emphasizing that the two can share the same goal: to bring science to the public.

During sessions in the Columbia Journalism School “World Room” where the Pulitzer Prizes are announced each spring, Herbstman and Tu helped a cohort of students (those studying public health and those with a journalism focus) to understand the differences, and similarities, in the two fields. “What is the role of an editor versus the role of a peer reviewer?” Herbstman says. “How is grant writing different from pitching in a journalistic setting?”

Herbstman, who explained the life cycle of a research study for the students in the class, says the biggest difference between the fields is the time frame in which they work. “Journalists call me and they need information by this afternoon,” Herbstman says. “But from an idea to a research paper can be five-plus

Over the last year, Columbia Mailman School faculty have taken on a remarkable range of topics and written for a wider audience than ever.

Read excerpts from their work.

years. How do you make that newsworthy today?”

“Losing your first tooth is a rite of passage for many children. But what if we never talked to them about this normal part of childhood? ... Imagine if, instead of rewarding children with a dollar bill, our silence and stigma led them to hide this experience out of embarrassment. ... This lack of knowledge, insufficient support, and feeling of shame are exactly what many people experience when it comes to periods.”

MARNI SOMMER, DrPH ’08, MSN, RN, professor of Sociomedical Sciences, and co-author Joanne Armstrong, MD, MPH, in Fortune

By the end of the course, each student had written a journalistic story about a scientific article, working with editors from Scientific American and Forbes to polish the pieces as if for publication. Herbstman says she hopes the course inspires future public health professionals to work with journalists to communicate their research. “Otherwise, the impact of our work is limited to the handful of people who are on PubMed,” a massive database of scientific literature.

Herbstman talked about the course as a member of a panel on bridging the gap between scientific information and public understanding held as part of the Health Policy

and Management Healthcare Conference last April, another sign of the School’s vigorous interest in this topic. Moderated by Robert Shepardson, senior lecturer in Health Policy and Management and co-founder of the advertising agency SS+K, the session also featured Kevin Munoz, assistant press secretary at the White House.

During the panel, Munoz emphasized how today’s “deeply fragmented media environment” called for meeting people where they are to communicate valuable health information. “You need to be in the tabloids. You need to be

“Graduates of for-profit institutions … are not achieving the same labor market outcomes as their counterparts from more traditional colleges and universities [even though] their institutions were held to the same academic accreditation standards. With this in mind, the next time your admissions or hiring committee excludes or scoffs at applicants with online degrees, think twice.”

ROXANNE RUSSELL, PhD, adjunct assistant professor of Health Policy and Management, in Inside Higher Ed

on TikTok, Instagram. All of these are going to play a role in how you communicate about public health issues,” he said.

For a long time, many public health professionals believed sharing their work meant talking about their scientific findings with graphs, data, and statistics, but without interpretation. “They would assume that public health information could speak for itself,” says Gina Wingood, ScD, MPH, the Sidney and Helaine Lerner Professor of Public Health Promotion in Sociomedical Sciences, director of the Lerner Center for

“If you were to go to buy a $1 chocolate bar but were told it would actually cost $6, you would probably complain about the $5 difference and refuse to pay it. But if you were buying an airline ticket priced at $250 that turned out to cost $255, you would be more likely to proceed. This illustrates the widespread and influential phenomenon of ‘mental accounting,’ which helps explain why individuals, institutions, and societies perceive the value of money as relative to its origin and purpose.”

KAI RUGGERI, PhD, professor of Health Policy and Management, in the Financial Times

“The

implications of climate change on HIV health outcomes have not historically been made obvious, but as an international development community, we are beginning to see the range of risk behaviors associated with climate change impacts, especially among women. We have a responsibility to establish programming that reflects what we know.”

ANDREA LOW, MD, PhD, adjunct assistant professor of Epidemiology in ICAP, in The Hill

Public Health Promotion, and director of the Health Communications Certificate. But if the COVID-19 pandemic left public health professionals with one lesson about communication, Wingood says, it’s that the public needs help interpreting scientific findings (not to mention parsing jargon).

An example of COVID-19 communication done right: the wildly successful Dear Pandemic, a social media campaign co-founded by Sandra Albrecht, PhD, assistant professor of Epidemiology, to combat misinformation about COVID-19. Albrecht was part of an interdisciplinary team of researchers and clinicians who took to Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram in the early days of the pandemic to deliver factual information in nonpartisan, accessible language for the public.

A winning formula for public health communications, Wingood says, includes using messages from trusted messengers that address social determinants of health, appeal to the reader’s emotions, and include visuals that tell the story— and reaching out across a diverse array of communication channels. For instance, she says, information for older adults could use compelling narratives directly from older adults. “There’s no monolithic audience who’s going to respond in the same way,” Wingood says. “Public health messages need to be framed for diverse audiences. Health literacy is another underestimated problem. Messages should use nontechnical language and aim to motivate a single action rather than a lifestyle change. Health literacy is a cornerstone of messages

On a sense of purpose

“Research shows that having more sense of purpose in life, and of control over one’s life and health (a so-called internal locus of control), are associated with better physical health, including less disease, pain, strokes, dementia, and Alzheimer’s. Yet, while many people find such purpose through reliance on faith and traditional religions … it can consist of social and political ideals as well.”

created by the Lerner Center’s founder, the late Sid Lerner, an advertising-industry legend.

Columbia Mailman School students practice designing compelling health messages by competing in the Lerner Center’s annual Health Messaging for Justice competition, which challenges students to create products that reduce stigma, enhance social justice, and counteract racism. This year’s submissions spanned communication products ranging from a documentary on transforming spaces for accessibility, to a “get to know you” card game for new sexual partners.

The student competitors, who came from across departments, were scored on messaging, creativity, design, and dissemination strategy, topics frequently covered in their coursework, Wingood says. The winning submission came from Jazmyne Bullock, Courtney George, Ugomma Korie, and

On racism in drug policy

“At face value, New York’s Good Samaritan law seems like an important step towards harm reduction; however, upon closer examination, it simply masks an ongoing mandate to criminalize drug users.”

JOHN PAMPLIN II, MPH ’14, PhD ’20, assistant professor of Epidemiology, on Thirteen.org

Megan Spinella (all ’25); their submission, Health, Happiness, and Life: A Guide for Expectant Black Mothers in NYC, is a free podcast that melds personal stories with expert interviews. The student winners “were excellent at integrating issues of health literacy and tailoring their podcast to the audience of African American women,” Wingood says.

Students can study health communications in single courses or through the Health Communication Certificate, where they learn about mobile health, email marketing, data visualization, and infographics, and how to tackle misinformation. Graduates of the program, which offers extensive exposure to health communications experts across New York City, have gone on to careers in city and national health departments, in the media, and at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as at digital communication agencies, healthcare companies, and nonprofits.

Health communication courses include the long-running Writing for Publication in Health Policy and Management, which was recently taught by Maria Smilios, author of The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis. Every full-time Health Policy and Management student takes a professional development course called PIVOT that helps them learn to communicate about their work through mock interviews and simulated conversations. “Everybody’s searching for different ways of communicating with different audiences,” says Sparer. “There’s much greater attention being paid now, among academics, to how to more effectively reach the consumers you want to reach.”

Christina Hernandez Sherwood specializes in journalistic storytelling. See more at christinahernandezsherwood.com. Additional reporting by Neha Kumar, MHA ’24.

Metals are at once essential and unavoidable in our environment. Now a growing body of research at Columbia Mailman School is uncovering their health risks— and exploring state-of-the-art antidotes for overload.

By Carolyn Wilke

Present in the Earth’s crust since our planet formed, metals are everywhere. They occur in soils and rocky ores. They circulate in the water we drink and the air we breathe. Our food—from vegetables to grains to fish—carries metals too. Our daily activities expose us to metals, in our surroundings and in commercial products. (A new study at the School even found metals in tampons.)

“These are really important environmental exposures,” says Ana Navas-Acien, MD, PhD, MPH, Leon Hess Chair and Professor of Environmental Health Sciences. And with its myriad biological interactions, the metallome— the array of metals in our bodies— is crucial to human health.

Many metals are essential for life, such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Others, including copper, zinc, and iron, are required in small amounts. As parts of proteins and enzymes, these metals enable the chemical reactions that keep us alive.

But the body’s relationships with some of these substances can sour if they are present at too high a concentration. Meanwhile, other metals and metalloids are toxic at even low levels. These elements—lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic—can wreak havoc on cells and tissues.

Human activities, such as mining or burning fossil fuels, can liberate metals, including toxic ones. As chemical lookalikes of essential metals, harmful metals can interfere with biological processes. For instance, lead mimics calcium while cadmium imitates zinc. “That’s one of the key ways in which they induce toxicity,” Navas-Acien says.