ERICA MCKEEHEN

2023 THESIS EXHIBITION

COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO

Photography MFA

JESSICA HAYS

BODY BREEZE EARTH MICAHMCCOY

COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO PHOTOGRAPHY MFA GRADUATING CLASS 2023 Jessica Hays Erica McKeehen Micah McCoy 3-14 15-28 29-42

© Columbia College Chicago 2023 Printed and bound in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Columbia College Chicago Photography Department is proud to present the 2023 MFA Thesis Exhibition Catalogue which showcases the work of three emerging artists: Jessica Hays, Erica McKeehen and Micah McCoy.

These artists confront their audiences with work that brings into view important issues from underrepresented populations; work that challenges societal expectations; work that confronts the threats of climate change; and work that transcends our experiences of everyday life. These artists challenge us to question the world through their own lens. Focusing on drought conditions that are endemic across the Western United States, Jessica Hays’s work raises questions about the fragility of our planet and our collective responses to the immediate concerns of climate change effecting our daily lives. Micah McCoy’s work, loosely based on the JudeoChristian story of Job, witnesses a family faced with existential crisis in a chillingly desperate landscape. Blurring the line between traditional documentary and the fictional, McCoy’s photographs allow the individual characters portrayed to function as surrogates in mythmaking. Erica McKeehen’s photographs of the Chicago burlesque community, including herself, work to de-stigmatize how burlesque and broader topics related to sex work are talked about and viewed in our society.

The variety of form, subject matter and issues included in this catalogue are evidence of the Columbia College Chicago MFA Photography Program’s mission to support artists with diverse ideas. These three artists have succeeded in producing work that, although varied in theme and approach, is powerful and poignant.

The work of these artists has been generously supported by the dedicated staff and faculty of the Photography Department. The renowned Museum of Contemporary Photography staff have been an integral part of the program and have supported each of these artists along the way. We thank everyone who has given their time, including the many professionals from greater Chicago cultural institutions; the national and international visiting artists, critics, and curators whose interactions with these artists has been invaluable; and the writers whose essays accompany each artists’ work in this exhibition catalogue.

It is with great pride that we congratulate the graduating Columbia College Chicago MFA in Photography class of 2023.

Kelli Connell Graduate Program Director

JESSICA HAYS

The Sun Sets Midafternoon

Because we tend to concentrate our attention on the things depicted in a photograph – the accumulated stuff that existed, at least for an instant, in front of a camera’s lens – we don’t often consider the fact that the photographer was yet another thing that was present at that very same location at the moment of exposure.

The depicted things in a photograph constitute its subject matter, and it is usually (though not always) easy to convey subject matter in language. Whereas the (undepicted, yet undeniably present) mind of the person behind the camera manifests as form. We have a hard time using our words to discuss form in a photograph, just as we struggle with describing the ineffable richness of the interior of any human being.

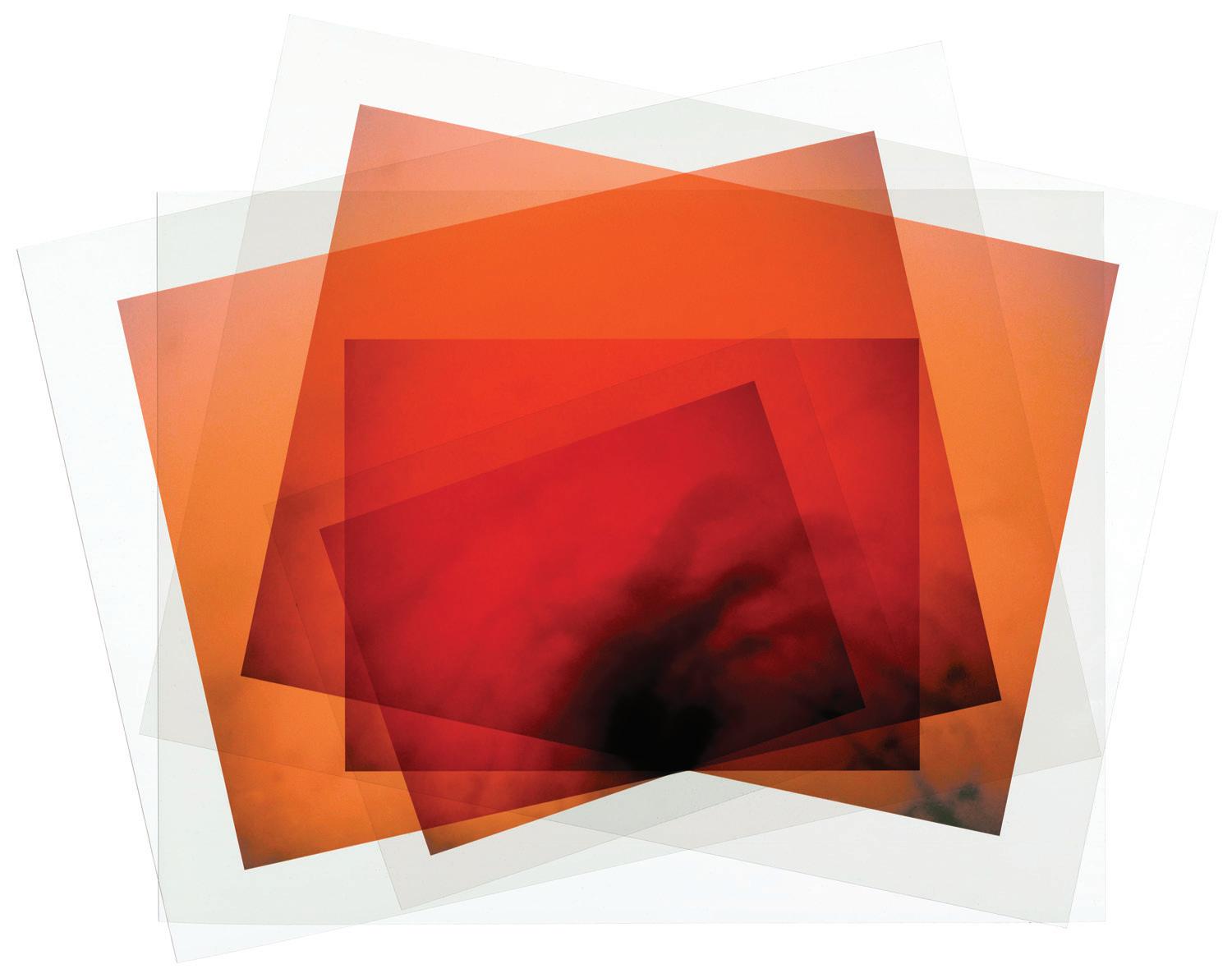

The achievement of Jessica Hays in The Sun Sets Midafternoon is twofold: first, she adroitly portrays a dire and unsustainable situation that we continue to ignore at our own peril. If her sole objective is to heighten our attention to not only the devastation wrought by massive wildfires, but also to the larger environmental crises that such fires portend, then – in these harrowing and heartbreaking photographs – she has succeeded. But what I want to suggest goes further than that, to the essence of her photographic endeavor. In these pictures, Jessica depicts herself and her self – evoking (and not just describing) her fully inhabited and highly idiosyncratic relationship towards this world and her (and thus our) tenuous place in it. And it’s in this way that she elevates her already potent subject matter and really twists the knife; these are not photographs that we can easily shake off.

At the risk of stating the obvious: Jessica placed her body (and her machine) in these situations. We needn’t know if she was ever in real danger to nonetheless surmise that her footing was not always secure, and that her skin baked in the intense heat, and that the smoke stung her eyes and nostrils. She herself became a part of the conditions – beyond all intellectualizing or narratizing of the science or history of fires and climate change –and the photographs she made are formal realizations of her embodied presence.

Note, for example, how Jessica estranges us from classically beautiful landscapes by offering instead seemingly unearthly colors in the skies, or atmospheres of choking thickness, or smolder and char – that we can smell, that we can feel – as far as the eye can see. (Or, similarly, in the Horizon Line book, how she deploys very large and long prints that bleed to the edges in order to immerse the viewer not only in a visual experience, but in a physically grounded one of turning the expansive pages.

This estrangement that Jessica enacts in her pictures is persuasive because it is informed by a unique perspective – it literally springs from her history. She writes: “Begun after experiencing the devastation of a wildfire in my hometown, this work explores solastalgia, which describes emotional and existential distress caused by negative environmental change, generally experienced by people with lived experience closely related to the land.”

Thus we see how an otherwise “topical” examination of fires and climate crisis becomes uncanny in the hands of the photographer who allows (invites) pre-reflective personal perception to inform her picture making. Uncanny because entirely individual to the maker, and yet formally palpable to the viewer.

And that broader connection to an audience is important to Jessica, who, as part of her practice, speaks on issues of mental health, trauma, relationship, loss, and loneliness. After grasping the initial call to arms conveyed in these photographs, we come to recognize that they are simply too beautiful – too wholly thoughtful – to express grief alone (although it is certainly there). In The Sun Sets Midafternoon, Jessica Hays shows us that a real love and reverence for the land is the foundation of hope, and of any real possibility of change.

Tim Carpenter, April 2023 Photographer, Writer, and Educator

Downed Line, 2020

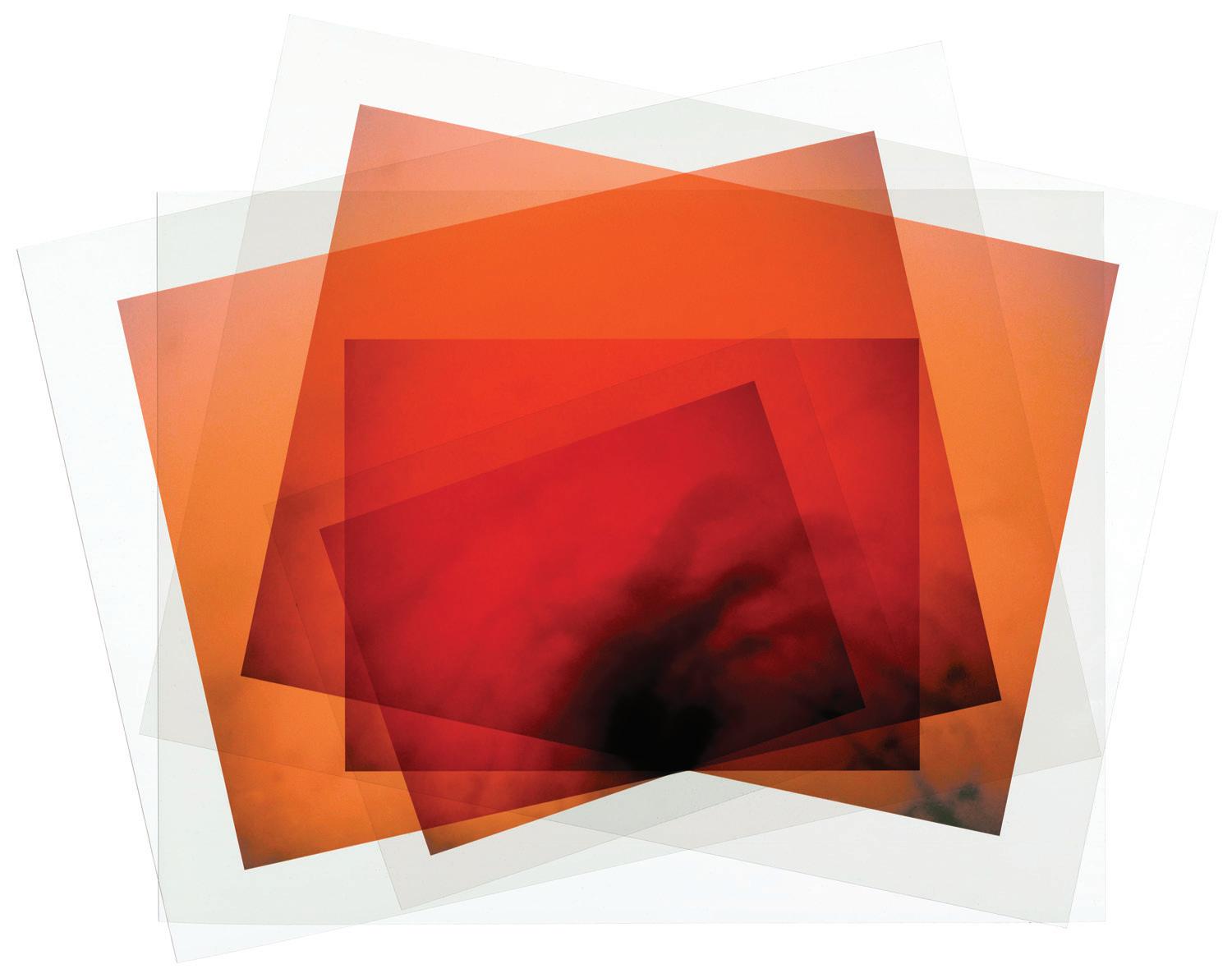

Red Rain, 2020

Alder, 2022

Red Rain, 2020

Alder, 2022

Murmuration, 2020 (following page)

Field Fire, 2022

Field Fire, 2022

White Bark, 2022

Fireweed, 2022

One Year, 2022

Splinter, 2021

Caution Zone, 2021

White Bark, 2022

Fireweed, 2022

One Year, 2022

Splinter, 2021

Caution Zone, 2021

Burnfall, 2021

Downfall, 2022 Ghosts, 2020

Burnfall, 2021

Downfall, 2022 Ghosts, 2020

Solar, 2020

Solar, 2020

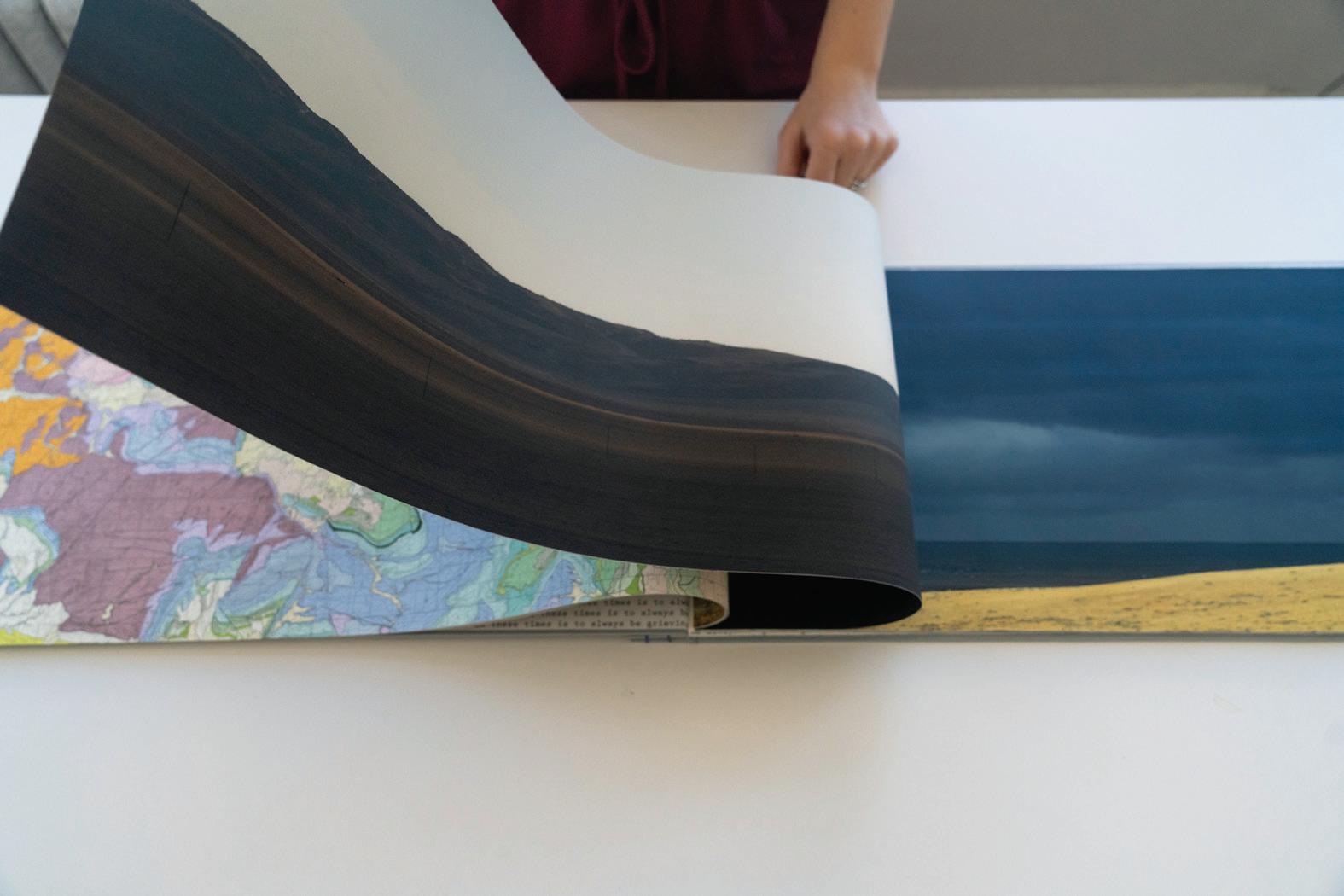

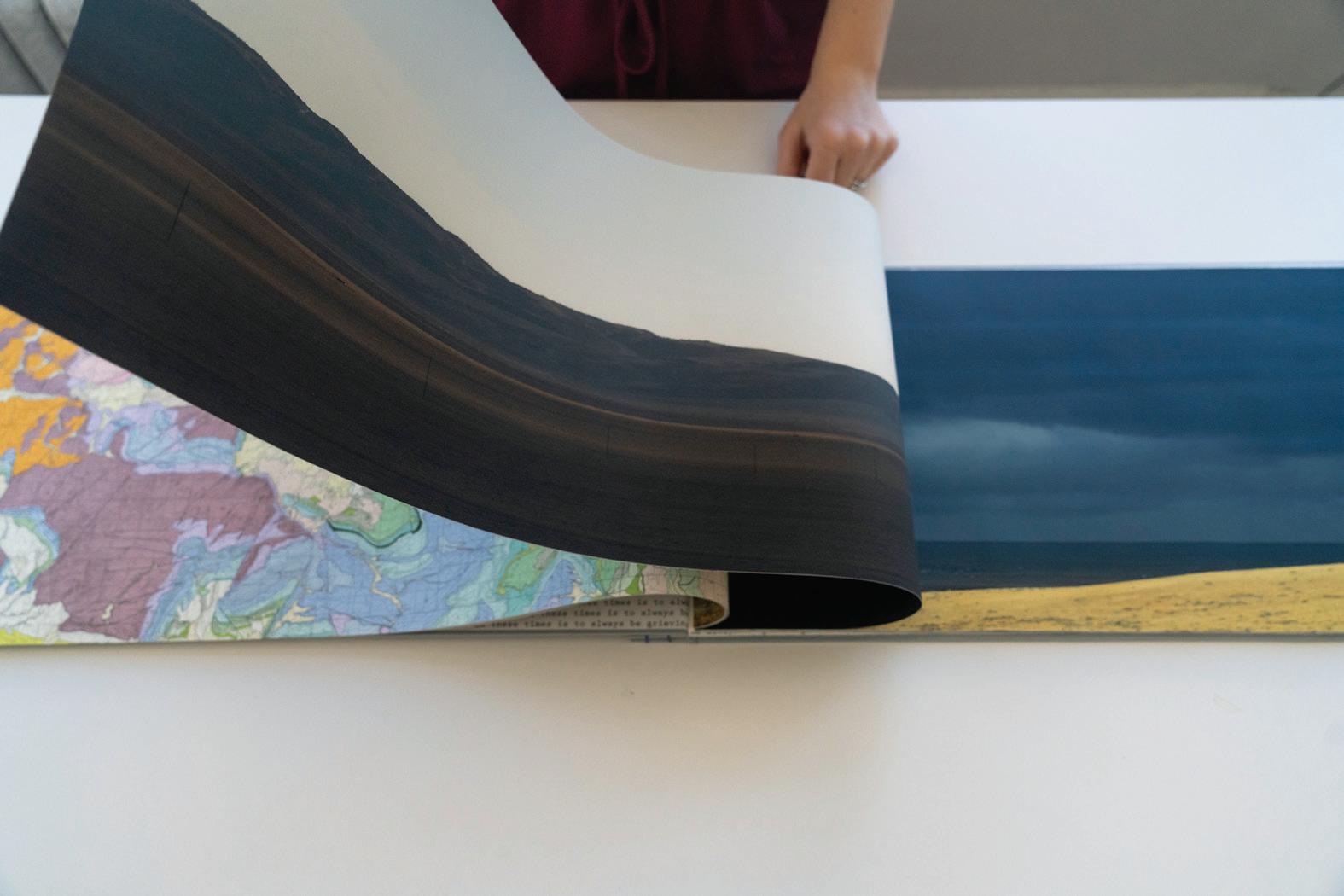

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Cover, 2023

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Interior View, 2023 (above)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, First page view, 2023 (right)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Cover, 2023

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Interior View, 2023 (above)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, First page view, 2023 (right)

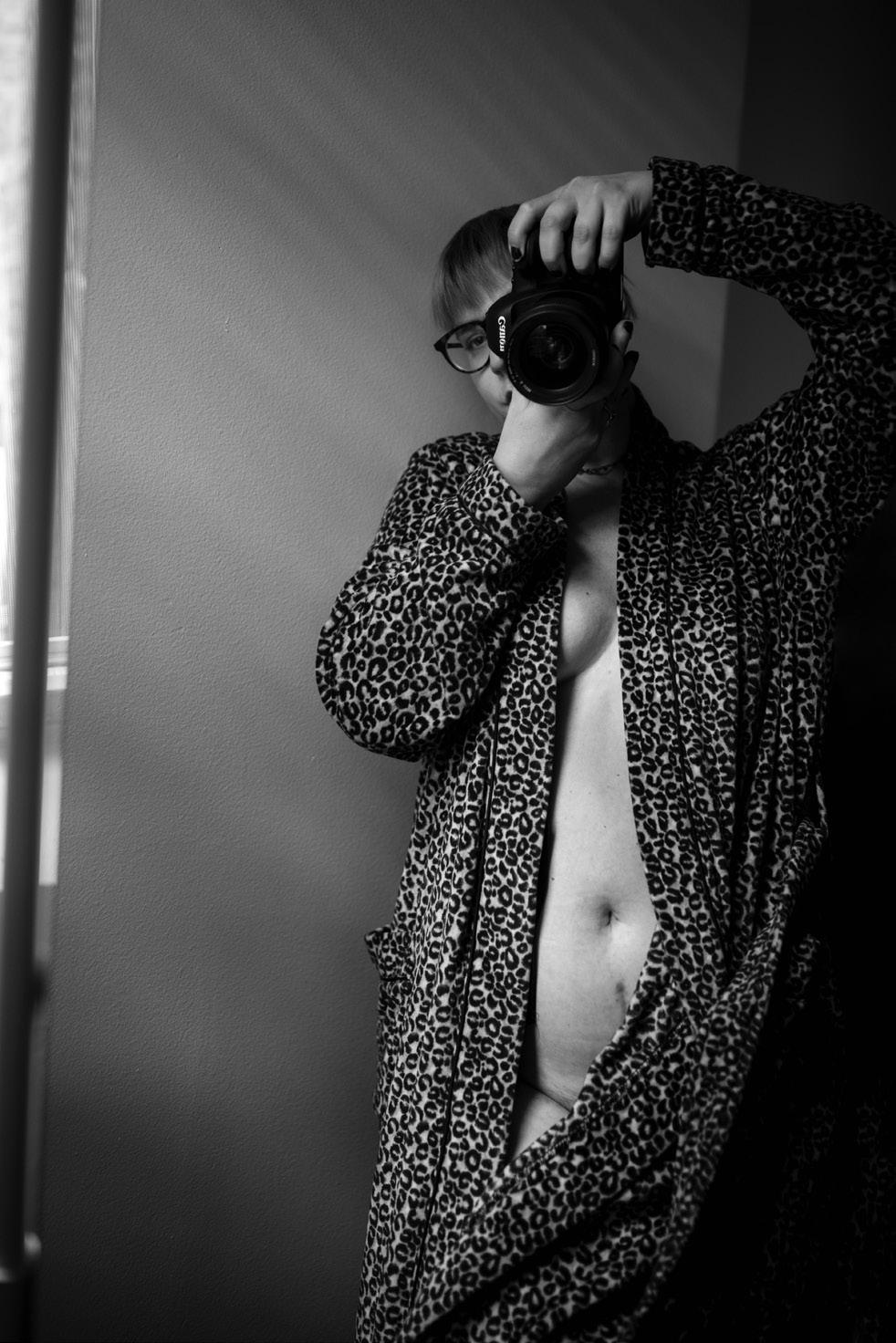

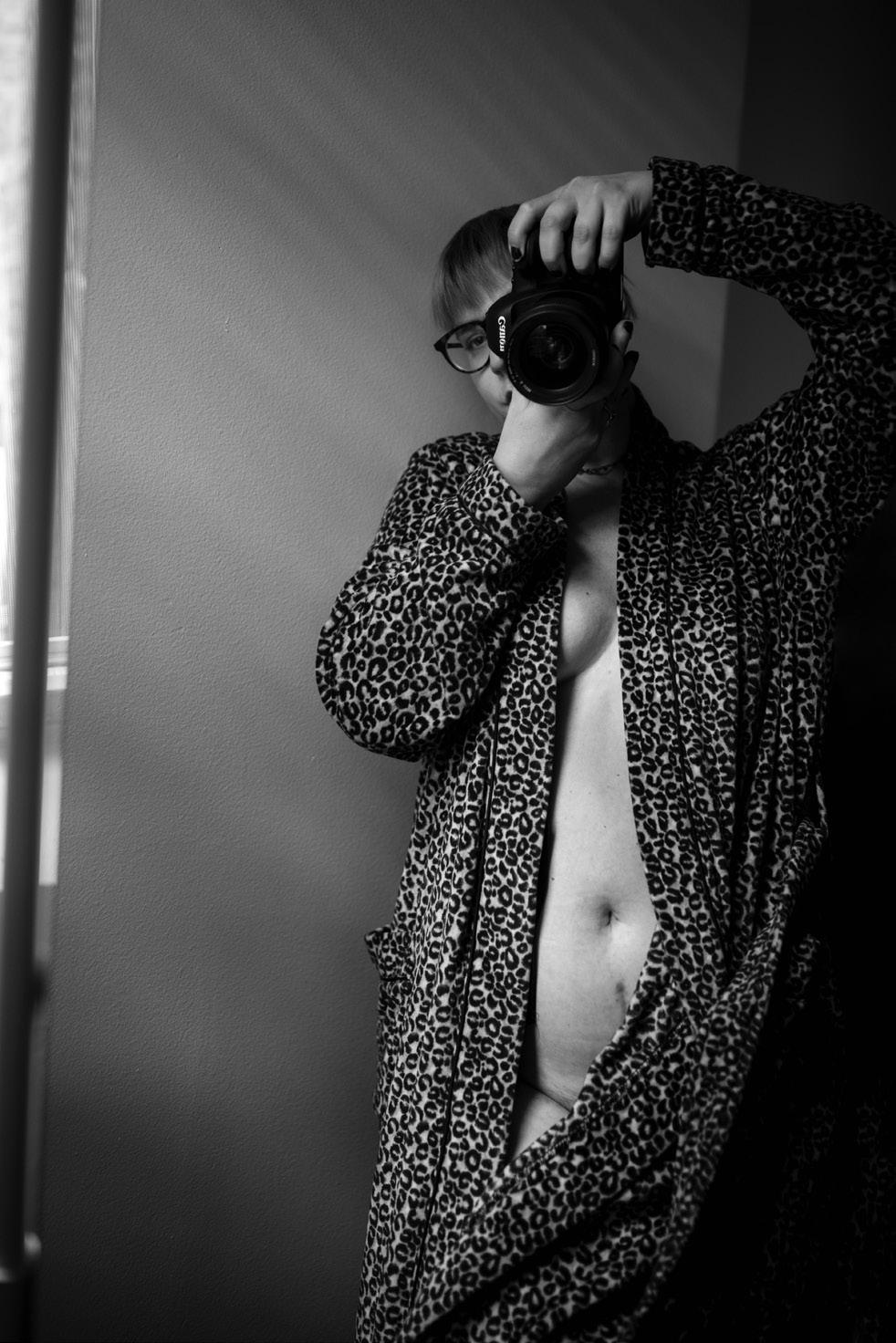

ERICA MCKEEHEN

Erica McKeehen was born in rural Ohio in 1987, during the Reagan administration and before the internet was accessible in most households. Common for many creativetypes who are stuck in small towns, she immersed herself in art wherever she could find it—in movies, music videos, and magazines. McKeehen was most drawn to imagery of provocative women, such as Madonna and Marilyn Monroe, who proudly display their sexualities in front of the camera. Fast forward twenty-or-so years later and she is in graduate school studying photography, and still compelled by unapologetic women. But instead of admiring celebrities from the distance, she found herself in the audience of live burlesque performances.

Burlesque is a variety show comprised of acting, comedy, and striptease. The performers play with the power of suggestion, celebrating female sexuality as out in the open, but not up for grabs. This version of the artform dates back to the mid-19th century where performers then parodied popular theater or opera shows, mocking heroes like Shakespeare, while also foregoing the constrictive clothing of the era for more risqué skirts that put legs on full display. Burlesque changed over time and the striptease became a mainstay in the 1920s.

McKeehen was first introduced to burlesque soon after the election of Donald Trump, and the performance resonated with her as a powerful antidote for her fears of what the new presidential administration could mean for women’s rights. She began performing shortly after, and this part of her life naturally made its way into her visual art practice. McKeehen started creating a photographic index of fellow burlesque performers, and then dozens of images of one performer, Katina, who became her closest friend and muse. In these images, we see Katina in the many locations that she inhabits or has inhabited—a Chicago apartment she shares with her husband, a flat on the southern coast of Spain, her childhood home in Michigan, the backstage rooms of venues. In each, we see an undeniable care between photographer and photographed. We sense the passing of time and know that McKeehen spent many hours waiting for the light to fall just right.

Over time, McKeehen realized she was tackling something bigger than documenting her friends and fellow performers. She found that her depictions added an important perspective that contrasts with most representations of sex workers. While digging through archives and art history textbooks, she found a trove of images of sex workers portrayed anonymously—fully nude except for a mask over their faces, or with their heads cropped entirely out of the images. These photographs leave little room for a viewer to form an empathetic connection. Alternatively, she found images of sex workers portrayed as victims living on the streets or in squalor, who appear to need someone to swoop in and save them. These photographs can perhaps create empathy in the viewer, but they also potentially equate sex work as an industry that is only a last choice. McKeehen firmly establishes her practice as counter to either of these extreme representations, and hopes to show us that sex work, like all professions, is complex.

She states: “I resist voyeurism and spectacle and instead explore creative camaraderie and community through nuanced views of femme experience, sexuality, and autonomy.” We see this nuance in images of Secret Mermaid, who is pictured playing video games or lounging at home, displayed alongside images of her go-go-dancing in dimly-lit clubs. McKeehen does not explain the difference in occupation between Secret and Katina, because she doesn’t feel like she should have to. She wants us to push against our own notions of what sex work should look like, and to see the stories she presents with fresh eyes: A person on the phone. A person sewing a costume. A person holding hands with their partner. A person getting ready to go out at night. An occupation. An occupation of choice. An occupation of choice that can be profoundly feminist. These images remind us that if we can understand female sexuality as something joyful and not shameful, we can broaden our worldview beyond dominant patriarchal and puritanical standards. A powerful suggestion indeed.

Kristin Taylor Curator of Academic Programs and Collections at the Museum of Contemporary Photography

SIze 5 and 1/2 (from Secret Mermaid ) , 2022

Kristin Taylor Curator of Academic Programs and Collections at the Museum of Contemporary Photography

SIze 5 and 1/2 (from Secret Mermaid ) , 2022

Here Lately ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (above)

Country Life ( from Days of Rust), 2022 (top left) Disco Sunday ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (bottom left)

Here Lately ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (above)

Country Life ( from Days of Rust), 2022 (top left) Disco Sunday ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (bottom left)

Pillowcase ( from Days of Rust), 2023

Strange Desire ( from Days of Rust), 2022

Pillowcase ( from Days of Rust), 2023

Strange Desire ( from Days of Rust), 2022

Hair Dye ( from Days of Rust), 2021

Hair Dye ( from Days of Rust), 2021

Cover Me ( from REVEAL), 2022 (above)

Kitty and Greta ( from REVEAL), 2022 (left)

Cover Me ( from REVEAL), 2022 (above)

Kitty and Greta ( from REVEAL), 2022 (left)

Only Sour Cherry ( from REVEAL), 2018 (above)

Valencia, Spain ( from REVEAL), 2022 (right)

Christmas Party Kiss ( from REVEAL), 2022 (overlaid on right)

Only Sour Cherry ( from REVEAL), 2018 (above)

Valencia, Spain ( from REVEAL), 2022 (right)

Christmas Party Kiss ( from REVEAL), 2022 (overlaid on right)

Curtain ( from REVEAL), 2022

Bordel ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022

Curtain ( from REVEAL), 2022

Bordel ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022

These Dreams ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (above) Gig Suitcase ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (left)

These Dreams ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (above) Gig Suitcase ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (left)

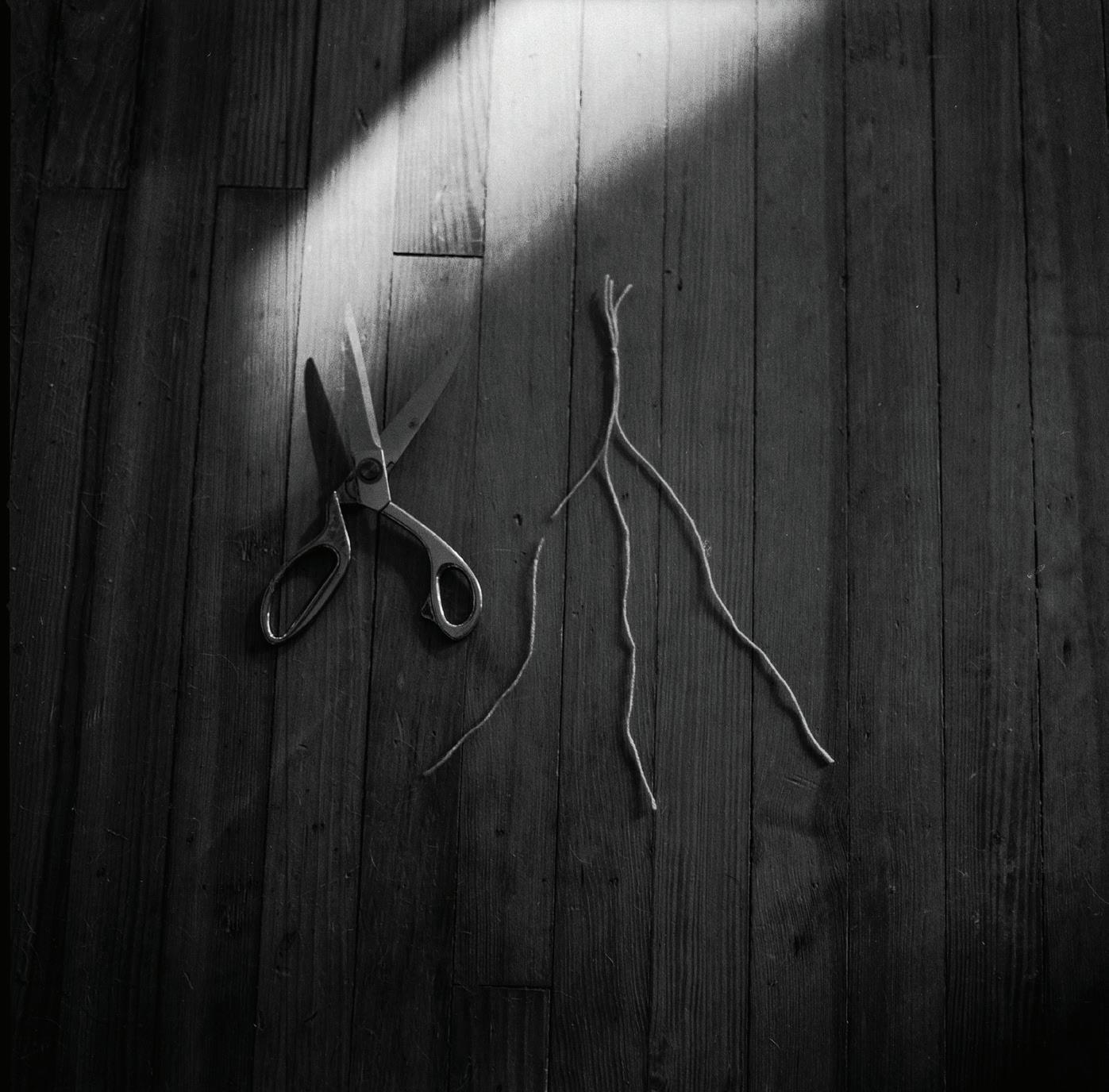

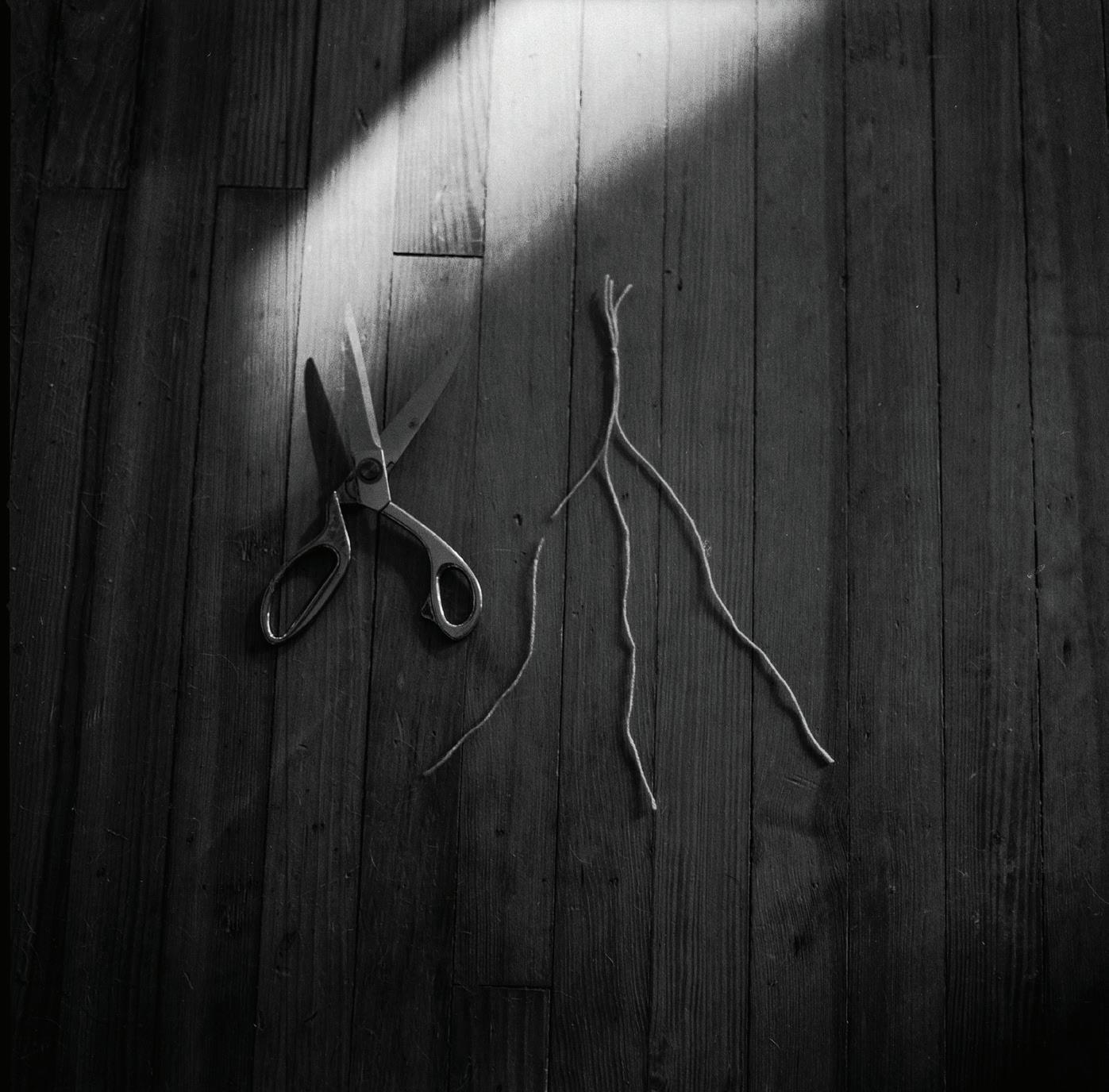

MICAH MCCOY

“Men sat in the street wagering their souls all / while I just wanted to wake up. / I’ve been here before across the bridge to home,” Micah McCoy writes in one of the poems that bears a weight equal to that of his photographs in Minor Prophet. Implausibly enough, I too have been here before; he and I are from towns just 15 miles apart in a central Illinois county of fewer than 17,000 of those souls.

So I know this landscape intimately. What I don’t know is the world of this work. At least not yet, even after repeated viewings (a state of affairs which I enjoy very much). That’s because – as is proper – Minor Prophet is not “about” any particular place on the face of this earth. Which is to say that it is not descriptive of a location, but rather evocative of a situation that pervades both inside and outside the maker – an ultimately unresolvable situation at that.

There are four “characters” (whom we meet in staged photographs that subtly suggest interiorities that are perhaps not entirely frictionless with one another) and they appear to be a family. Still life pictures – of scissors, or of some communion wafers – portend without too much specificity. The plains are nondescript, and although we recognize a variety of seasons, this work does seem to me to have a mind of winter; one hears misery in the sound of this wind.

Nostalgia is often supposed of (or imposed upon) black-and-white photography, but here the tensions and ambiguities are simply too fresh, too wholly present, to belong to any history. “I do desire to summon a wistfulness but if the pictures relate in some way to the past, I think their primary dialect is regret,” Micah says. What’s done is done, but regret is the inescapable echo of what’s done. It stays always close to hand.

Now – mind you – all of this is the artist’s creation. The actual members of his family, and the actual home and land which they inhabited, have nothing to do with this. Micah is a photographer, and the gift/curse of his camera is that he can (must) make use of the absolutely real to convey the absolutely unreal. As proof: “I didn’t really learn anything new about myself or my family while making this work,” he notes. “I had pictures in my mind that I wanted to make, that I believe say certain things.” This, I believe, is why we photographers choose to work with and through our strange machines. To make pictures – which are new things in the world, and different in kind from that world – not mere documents of things already existent.

Speaking to the core of this work, Micah describes “a family faced with existential crisis in a chillingly desperate landscape.” Every unhappy family is for sure unhappy in its own way; I submit that every artist is similarly broken in his or her own way. Minor Prophet stands plainly as evidence of Micah McCoy’s brokenness, and – more importantly – as testament to his longing to make tenuous communion (to wager his soul) with the people and places that are the stubbornly actual stuff of this world, which is the only one we have.

Tim Carpenter, December 2022 Photographer, Writer, and Educator

Tim Carpenter, December 2022 Photographer, Writer, and Educator

THANK YOU

The Photography MFA Class of 2023 would like to extend our gratitude to the following people for their continued support and guidance throughout our education at Columbia College Chicago:

Christina Z. Anderson

Todd Anderson

Evan Baden

Laura Bauknecht

Aimee Beaubien

David Belmar-Medez

Dawoud Bey

Bob Blandford

Joseph Bogdan

Carol Boss

Whitney Bradshaw

C. M. Burroughs

Ingrid Burton

Alison Carey

Tim Carpenter

Jonathan Castillo

Daniel Coburn

Stephanie Conaway

Kelli Connell

Paul D’Amato

Margaret Denny

Grace Deveney

Katina Donoghue

Carolyn Drake

Natasha Egan

Odette England

Terry Evans

Jes Farnum

Peter Fitzpatrick

Nancy Floyd

Doug Fogelson

Gregory Foster-Rice

Marissa Fox

Andres Gonzalez

Shaul Guerrero

Megan Hansen

Asha Iman-Veal

Karen Irvine

David Johnson

Tom Jones

Barbara Kasten

Natalie Krick

Aviya Kushner

Jessica Labatte

Whitney LaMora

Lindsey Lee

Amy Leners

Pixy Liao

Robert Linkiewicz

Sally Marvel

Dirk Matthews

Lindsey McCann

Caitlin McCoy

Janie McCrae

Shannon McKeehen

Nick Meyer

Amy Mooney

Abelardo Morell

Jennifer Murray

Chris Nightengale

Niki Nolin

Ryan Parker

Colleen Plumb

Mimi Plumb

Kristine Potter

Melissa Potter

Christopher Rauschenberg

Odeth Reinoso

Richard Renaldi

Rebecca Reuland

Bailey Russel

Laura Santoyo

Ross Sawyers

Forrest Simmons

Royce Smith

Samantha Stawiarski

Dana Stirling

Kristin Taylor

David Trinidad

Ian van Coller

Carmen Winant

A special thank you to Hahnemühle for their generous donation of photographic paper for the Spring 2023 MFA Exhibition.

Photography Learn more at colum.edu/photomfa

MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHY

The Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) at Columbia College Chicago is the world’s premier college art museum dedicated to photography and has over 16,800 works in the collection. As an international hub, we generate ideas and provoke dialogue among students, artists, and diverse communities through groundbreaking exhibitions and programming.

Learn more at mocp.org

Photography, MFA

In Columbia’s graduate Photography program, students push their creative boundaries in a community of emerging artists.

Our fine art focus encourages students to develop their unique practice while also investigating the history, theory, and criticism of contemporary image making.

Elina Ruka MFA ’16

Elina Ruka MFA ’16

Red Rain, 2020

Alder, 2022

Red Rain, 2020

Alder, 2022

Field Fire, 2022

Field Fire, 2022

White Bark, 2022

Fireweed, 2022

One Year, 2022

Splinter, 2021

Caution Zone, 2021

White Bark, 2022

Fireweed, 2022

One Year, 2022

Splinter, 2021

Caution Zone, 2021

Burnfall, 2021

Downfall, 2022 Ghosts, 2020

Burnfall, 2021

Downfall, 2022 Ghosts, 2020

Solar, 2020

Solar, 2020

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Cover, 2023

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Interior View, 2023 (above)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, First page view, 2023 (right)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Cover, 2023

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, Interior View, 2023 (above)

Horizon Line, Handmade Artist Book, First page view, 2023 (right)

Kristin Taylor Curator of Academic Programs and Collections at the Museum of Contemporary Photography

SIze 5 and 1/2 (from Secret Mermaid ) , 2022

Kristin Taylor Curator of Academic Programs and Collections at the Museum of Contemporary Photography

SIze 5 and 1/2 (from Secret Mermaid ) , 2022

Here Lately ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (above)

Country Life ( from Days of Rust), 2022 (top left) Disco Sunday ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (bottom left)

Here Lately ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (above)

Country Life ( from Days of Rust), 2022 (top left) Disco Sunday ( from Days of Rust), 2021 (bottom left)

Pillowcase ( from Days of Rust), 2023

Strange Desire ( from Days of Rust), 2022

Pillowcase ( from Days of Rust), 2023

Strange Desire ( from Days of Rust), 2022

Hair Dye ( from Days of Rust), 2021

Hair Dye ( from Days of Rust), 2021

Cover Me ( from REVEAL), 2022 (above)

Kitty and Greta ( from REVEAL), 2022 (left)

Cover Me ( from REVEAL), 2022 (above)

Kitty and Greta ( from REVEAL), 2022 (left)

Only Sour Cherry ( from REVEAL), 2018 (above)

Valencia, Spain ( from REVEAL), 2022 (right)

Christmas Party Kiss ( from REVEAL), 2022 (overlaid on right)

Only Sour Cherry ( from REVEAL), 2018 (above)

Valencia, Spain ( from REVEAL), 2022 (right)

Christmas Party Kiss ( from REVEAL), 2022 (overlaid on right)

Curtain ( from REVEAL), 2022

Bordel ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022

Curtain ( from REVEAL), 2022

Bordel ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022

These Dreams ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (above) Gig Suitcase ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (left)

These Dreams ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (above) Gig Suitcase ( from Secret Mermaid), 2022 (left)

Tim Carpenter, December 2022 Photographer, Writer, and Educator

Tim Carpenter, December 2022 Photographer, Writer, and Educator

Elina Ruka MFA ’16

Elina Ruka MFA ’16