9 minute read

DK Salutes America's Garage Builders

Advertisement

This is a new series we will be doing trout the year in conjunction with the folks at Dennis Kirk titled “Unsung - Dennis Kirk Salutes The Garage Builders.” While there have been many articles in this very magazine about the creations of garage builders, few details about their lives make it into those stories, the history of the men and women who can’t leave well enough alone and what it takes to join the ranks of America’s

Garage Builders. Each of these articles will also include a full-length video interview with the subject. You can find the interview at https:// youtu.be/luYx5jiPj4U, and I invite you to hear his story in his own words. The following is my interpretation of our afternoon together celebrating the spirit of

Hand Made Motorcycles.

I’ve known Ed, or should I say Mr. Fish, for quite some time now.

Neither my wife nor I can bring ourselves to call him by his first name, not because he is our elder in years but because we have been the benefactor of his knowledge. Of course, for me, that has been mostly in the way of machine and fabrication skills, but for both of us, Mr. Fish has shown us better living through the things you do.

Ed started off life as a kid who just didn’t like sports or what most of his friends were doing at a young age until one of them let him ride a homemade scooter. Being in the fifties, there wasn’t such an animal as a minibike yet; these kids were inventing what would hold fast as a sub-culture to this very day. Being from South Western Pennsylvania, Ed Fish grew up in a culture of hard-working blue-collar folks with that can-do attitude, a feature that would be reinforced in him at a young age. Early on in school, only 9th grade, in fact, Ed found himself in shop class where they had a welder that even the teacher didn’t know how to use. Ed

already knew from the things he had been tinkering with that if you could weld, you could do anything, so when the teacher threw him the book, Ed went straight to work on learning the skill.

Ed tried college for about one semester but quickly decided that he didn’t like it and never felt like he fit in. By trade, he became a machinist/tool and die, maker. Starting on that path in 1966, he went to work at ALCOA in New Kensington, PA. Eventually, he received his journeymen’s papers from them. This was the first plant to make aluminum in the world and was called Works 1. Of the many stories you’ll hear about the steel industry in Pittsburgh, ALCOA had a significant impact on the industrial revolution with an ally that Andrew Carnegie himself advised not to waste time on. ALCOA was right across the river from another great Pittsburg icon, PPG. With Allegheny Ludlum right up the road from them both, the Allegheny Valley became a hotbed of factory workers and row house full of their families. If you had a job in one of those three plants, you did well. Most area people were able to drive nice cars and bikes thanks to those jobs with little to no previous education. When the ALCOA plant locked the doors in 1971, it was a tough blow to the community. In his free time, Mr. Fish loved to race motorcycles. This part of the country is known for two of the most legendary cross-country races; The Fireball and the Blackwater 100. These were early versions of what would eventually become the AMA’s GNCC races. In the day, they were referred to as “Hundred Milers” and ate motorcycles like handfuls of popcorn. He got a Class C license racing flat track, road racing, and competing in some of the first cross-country races. He started in ’67 in the Western PA Scramble Assoc. After a few years of that, Ed became quite a flat track racer and competed all over the mid-west through the mid-1970s. He said it was without much success, but his stories tell of a life lived to the fullest. For a while, he raced with the Springsteen Brothers, who were both great racers.

Of course, many of you will remember the legendary Jay, but Ed also raced against his brother Ken and said that he was equally good in the day. At the ripe old age of 28, Ed started to feel the strain of racing because most of the guys next to him were only 18 + and Mr. Fish commented that it doesn’t sound like that big of a difference but that many years on the race track makes a pretty big impact. Ed road raced in Daytona, Road Atlanta, and the Poconos before hanging it up, but his true love was always flat track racing.

During his time running around the country racing motorcycles, Fish would meet another important figure from motorcycling that got his start in Pittsburgh, Eric Buell. It was sometime between 1974 and 1976 when the two decided to start a company in Ed’s mother’s basement called Pittsburgh Performance Products. Eric’s dad was a patent lawyer who had a client that developed AL Clad, which was aluminum with a thin cutter layer of stainless steel. This revolutionized cookware with the Al Clad brand of pots and pans, but Eric saw road racing brake rotors in this new invention. Together, Ed and Eric made disc brakes for racers who were obsessed with shedding weight. The product never quite took off, but it was an exciting time for them both. Eric and Ed were quite different personalities: Eric was haphazard and driven, and Ed was methodical and somewhat fussy. Being a machinist, he had a methodical way about him. Of course, Eric was fast as hell on the track. Ed said he almost rode too hard; he either crashed or won, but apparently, his pre-race condition was spent going just as hard at life, and chaos followed him all the day they knew each other. Once on a trip to Daytona, Ed had his bikes washed, polished, and ready to go while Eric shoveled his stuff into the truck and was ready to put the bike together on the trip down. Most people don’t know that Harley had bought an Italian company that sold a road racer RR250. They had an Italian rider and also had Eric Buell ride one for the factory team. At one point, Eric decided he was fed up. He dropped everything, went back to college to finish his degree, and got a job with Harley, and the rest is history.

Ed went out on his own and fulfilled his dream to own his own machine shop. He added buildings onto the family property, where he operated his shop for the next 47 years. At one time, he was able to employ 11 workers and made everything from farm equipment to parts for the railroad industry. He retired from the shop at the age of 72 and now spends his days restoring old Triumphs and taking the occasional odd job for machining.

Ed did a lot of motorcycle machine work, and in the 1960s and 1970s,

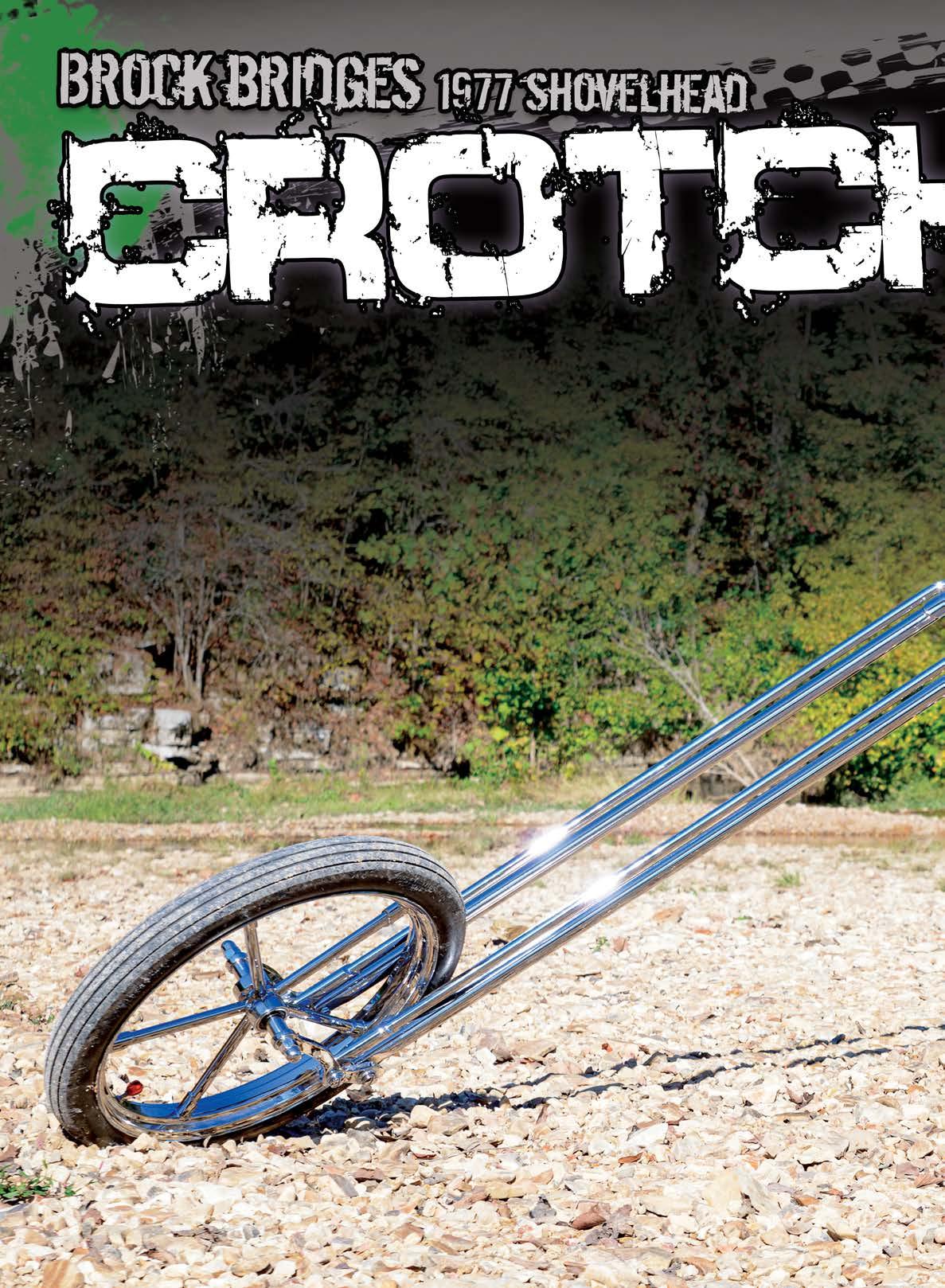

he met a lot of people that had their own small shops and were turning out great stuff. Ed actually wonders why the younger people today aren’t doing more of this like his generation did. He tells them not to start with an expensive top-shelf custom bike or car but to start small. There is a way you can afford it if you are willing to put the work in. He has only ever owned one new bike; the rest have been projects, including the Purple Yaffe style chopper in the photo. That bike was built with the help of his dear late friend Albert Moore; many will recognize that name from his days running “Albert’s Chrome,” which served the motorcycle industry for decades. Ed loves old Ironhead Sportsters done in a 1960’s style, but nothing does it for him like old Triumphs, especially the Triumph Cub. This 200cc trail model Triumph came along after the English company got news back from America in the late 50’s that they needed a better little bike than their current Terrier 155. Somewhere around the sixties, they came out with the Cub, and it took hold with the young crowd because it was light, fast, and cheap. Ed does these restorations today, one part a time with painstaking attention to detail. Because of the care he shows to the process, his builds are better than fresh off the floor when he is finished with them. No matter how big his machine shop ever got, Ed always kept his own little shop away from the work to do his projects. He says that this would save his employees his frustration by not being able to find things and being upset that someone might have moved his tools, but any true garage builder will understand what it’s like to have sanctuary in your shop, even if it’s smaller than the one you work in day in and day out.

We talked for some time about the garage culture that was such a big part of the area Ed lived in growing up and how so many guys back then did it out of necessity. There just weren’t big paint shops or performance shops like there are today, and a young man’s economy is quite a different thing as well. Many of Ed’s contemporaries did a lot of the work themselves. Small garages all over the area would be abuzz with sanders and welders, spraying paint and tuning carbs to get ready to cruise out and show off their creations to the world. The guys never cared about what was new or old; it was about what was cool and what you could do with it—even today. Ed doesn’t need or want the “new” big stuff…but he will race you to pick up that dusty old box of parts that he can use to build with. He gets a personal sense of pride and satisfaction from building something out of nothing, and probably always will.

NO THERE ISN’T ANY REAL PRIZE, JUST SOMETHING TO DO WHILE YOU’RE IN THE CAN.

1. Longer Tail On The Fuel Tank. 2. Missing Throttle Cable. 3. Color Of Fuel Line. 4. Extra Oil Line At Tank. 5. Rear Rocker Bolts Are Different. 6. Extra Oil Line At Base Of Cylinders. 7. Different Front Exhaust Pipe. 8. See Threw Air