5 minute read

Baxter's Garage Tells Us What To Look For

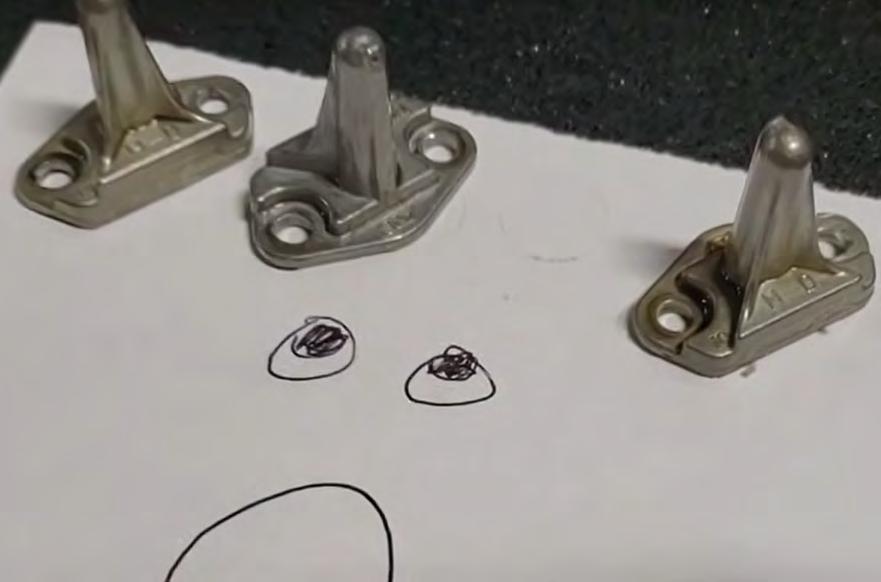

piston jets were first introduced in the twin cam and have carried over to the M8. They are a cast aluminum nozzle with a small ball and spring on the inside that acts like a check valve. Oil is fed through the cam plate, then through the engine case to the lifter bores, and finally to the piston jet, which sprays oil on the bottom of the piston. Their purpose is to help cool the piston due to leaner fuel mixtures used in later model engines.

For the most part, the twin cam piston jets function quite well with very few issues. However, many of you have most likely heard of the problems the early M8 engines had with the screws being too long, preventing the gasket from sealing. Oil would then pour into the crankcase constantly, and the oil pumps couldn’t keep up. Other issues I have seen include contamination from small pieces of case sealer that is used when cases are assembled and metal fragments along with a check valve that doesn’t operate properly. All of these can lead to sumping issues.

Advertisement

If the piston jets leak at the o-ring or gasket, or the check valve doesn’t function properly, they can also be a

Article And Photos By: Kevin Baxter

source of many other problems, including starving oil to the top end, noisy tappets at idle, and over lubrication of the cylinders. Over lubrication can negatively affect piston ring seal, increasing blow-by and oil consumption and promote sumping due to increased crankcase pressures. I have seen many complete engine failures caused by a malfunctioning piston jet, so this is a component you will want to pay particular attention to when you do an engine build.

The check valve should remain

closed until oil pressure reaches 13 to 15 PSI and then stay open above that. They are designed to work only above 13 to 15 PSI so that too much oil isn’t being sprayed into the crankcase at idle speeds. Also, since the jets get oil after the lifter bores, it can help keep the lifters pumped up when the pressure is at its lowest, which is at hot idle.

If you have a sumping problem or anytime you go into a top end which would give access to the piston jets, it is best practice to remove and test them. This not only confirms proper operation, but it also allows you to install a new o-ring for twin cam, or a new foamette gasket from Cometic on M8 models, as well as verifying proper screw length.

Your piston jets can be tested using a tool from JIMS. The easiest way to use the tool is to mount it in a vise with a set of soft jaws. You always want to make sure the inside of the tool is clean. There are two pipe plugs in it so you can flush it out with solvent. You can

test your piston jets with compressed air or oil to verify the spray pattern, ensuring even oil distribution on the bottom of the piston.

For this article, I randomly chose seven twin cam piston jets taken from engines with various miles on them. I used air for these tests. Four of the seven passed the test, and three did not. To test them, I slowly increased pressure. There should not be any flow from the piston jet until the gauge reads close to 13 PSI. Once the gauge reaches approximately 13 PSI, you should hear or feel a small amount of air flowing from the jet. At this point, you can steadily increase pressure up to 20 psi or more but not above normal operating oil pressure. You should easily hear air escaping from the jet, progressively increasing as more pressure is applied. Another way to see the airflow would be to apply a small amount of grease inside the port of the jet. When air begins to flow, the grease

will be pushed out of the port. If you are testing for spray pattern, use a sheet of paper behind the jet. A lot of oil will be sprayed, so be sure to have a pan of some sort to collect the drips.

You may be asking yourself, “How do I know if I have a leaking piston jet without having to remove the cylinders?” The unfortunate answer is, you don’t. You can, however, pay particular attention to how your motorcycle functions to provide hints that you may have a sumping problem that could be caused in whole or part by a leaking piston jet. If you experience intermittent power loss, feeling as if you’re dragging an anchor, notice a drastic loss or variance in fuel economy, excessive engine heat, or see your oil levels change drastically in a short period of time, that oil could be collecting in the crankcase. The loss in fuel economy and power is due to the resistance placed on the crankshaft having to churn thru oil. Your H-D is a dry-sump system meaning little to no oil should remain in the crankcase during normal operation. Still not sure if you may have a sumping problem? On M8, you can remove the crankshaft sensor from the bottom of the case. For twin cam, there is a pipe

plug that can be removed…but do it delicately as some have red Loctite on them, and you can crack the case or strip the threads if not done correctly. Little to no oil should drain from the crankcase. If you see more than a few ounces drain, you could very well have a sumping issue. Testing piston jets certainly has its value. If you’re having an engine built, ask your builder to perform this test. If you’re an engine builder, this is something that should be checked. At the very least, I would recommend removing them and replacing the gaskets or the o-rings on every engine when cylinders are removed. It could save you, your customer, and their engine. To see how this test is done on video, and for other great content, visit and subscribe to my YouTube Channel at www.youtube. com/kevinbaxter www.baxtersgarage.com