CENTER FOR POLICY ANALYSIS AND RESEARCH Criminal Justice and Economic Opportunity

CENTER FOR POLICY ANALYSIS AND RESEARCH Criminal Justice and Economic Opportunity

Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) represent a pressing environmental issue with negative impacts on community health, housing equity, economic opportunity, and social justice. Defined by the disproportionate concentration of heat in urban areas compared to surrounding rural landscapes, UHIs exacerbate existing environmental inequities and disproportionately impact marginalized communities (US EPA, 2014). As temperatures rise and climate change intensifies, understanding the relationship between urbanization, socioeconomic disparities, and environmental injustice is paramount in addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by UHI. This report examines the intersectional dynamics of UHIs and their effects on the Black community, exploring the underlying drivers, socioecological impacts, and policy implications of UHI-induced environmental victimization.

Urban Heat Islands are localized pockets of elevated temperatures within urban areas1 , contrasting with cooler temperatures in surrounding rural or suburban regions (US EPA, 2014). UHIs stem from the unique dynamics of urban landscapes. Buildings, roads, and other infrastructure act as heat sinks absorbing and re-emitting solar radiation in the community, surpassing the natural environments like forests and water bodies in their heat-retaining capabilities (US EPA, 2014). Due to the differential heat absorption and retention, urban areas emerge as “islands” of heightened temperatures.

Two distinct types of UHIs contribute to the temperature layering of urban environments: surface heat islands and atmospheric heat islands. Surface heat islands arise from the heightened absorption and emission of heat by urban surfaces, particularly roadways and rooftops, compared to natural surfaces (“Urban Heat Islands,” n.d.). Conventional roofing materials, for instance, can register temperatures as much as 60°F warmer than the ambient air temperature on a hot day, accentuating the intensity of surface heat islands. These heat islands typically peak during daylight hours when solar radiation is most pronounced (US EPA, 2015).

1 In this report, “urban areas” are defined as locations with high population density. The U.S. Census Bureau designates areas of 2,500 to 50,000 people as urban clusters and areas of 50,000 or more people as urbanized areas

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

Conversely, atmospheric heat islands result from the accumulation of warmer air masses within urban areas relative to the cooler air prevalent in surrounding non-urban regions. While less intense than surface heat islands, atmospheric heat islands contribute to the overall temperature layering of urban climates, influencing local weather patterns and atmospheric circulation (US EPA, 2015).

The following are key contributors to the formation and exacerbation of UHIs:

Reduced Natural Landscapes in Urban Areas: Trees, vegetation, and water bodies play a pivotal role in moderating temperatures by providing shade, transpiring water from plant leaves, and evaporating surface water, respectively (US EPA, 2015). Urban environments often feature extensive areas of hard, dry surfaces such as roofs, sidewalks, roads, buildings, and parking lots, which offer minimal shade and moisture retention. As a result, these surfaces absorb and radiate solar energy, contributing to elevated temperatures characteristic of UHIs.

Urban Material Properties: Conventional human-made materials utilized in urban environments, including pavements and roofing, exhibit low reflectivity for solar energy and high capacity for heat absorption and emission (US EPA, 2015). Throughout the day, urban materials accumulate heat and gradually release it, accentuating UHI effects, particularly after sunset. Natural surfaces such as trees and vegetation possess higher reflectivity and lower heat retention capabilities, mitigating temperature extremes.

Urban Geometry: The spatial configuration and layout of urban infrastructure significantly influence local temperature patterns (UCAR, 2021). The dimensions and spacing of buildings determine airflow dynamics and the ability of urban materials to absorb and dissipate solar energy. In densely populated urban areas, buildings obstructed by neighboring structures become thermal masses, impeding heat dissipation and exacerbating UHI effects. Additionally, cities characterized by narrow streets and tall buildings create urban canyons that restrict natural wind flow, further intensifying heat accumulation.

Heat Generated from Human Activities: Human activities, including vehicular traffic, air conditioning systems, industrial processes, and building operations, contribute to the emission of waste heat into the urban environment (US EPA, 2015). These anthropogenic heat sources augment UHI effects, exacerbating temperature disparities between urban and rural areas.

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

Weather and Geography: Meteorological conditions and geographic features play a significant role in shaping UHI dynamics (UCAR, 2021). Calm, clear weather conditions maximize solar radiation absorption by urban surfaces, intensifying UHI effects. Conversely, strong winds and cloud cover attenuate heat island formation by enhancing heat dissipation and reducing solar exposure. Geographic features such as mountains can modify local wind patterns and obstruct airflow, influencing temperature distributions within urban areas.

In recent years, the intersection of environmental victimization, particularly of marginalized communities, and the emergence of Urban Heat Islands has garnered increased attention within the realm of environmental justice. Environmental victimization refers to the intentional imposition of environmental hazards and injustices upon vulnerable populations, often perpetuated by discriminatory policies and practices, which include issues such as industrial siting, toxic waste hazards, redlining, and discriminatory landuse policies, all of which disproportionately affect communities of color. Urban Heat Islands, characterized by significantly higher temperatures in urban areas compared to surrounding rural areas, further exacerbate the environmental burdens faced by these communities. To fully understand and address these complex issues, it is important to examine concepts of environmental racism, which highlight how systemic inequalities and historical injustices contribute to the disproportionate exposure of Black communities to environmental hazards. Moreover, examining the social and psychological impacts of environmental victimization and racism on these communities, sheds light on the multifaceted nature of the challenges they face.

Environmental victimization involves the intentional use of zoning and placement practices to disadvantage impoverished and minoritized communities (Natali, 2015). This form of victimization comprises of three key components that diverge from conventional criminological perspectives (Natali, 2015). Initially, harm extends beyond individuals to encompass entire groups or communities.

Second, perpetrators of environmental harm often include corporations or governmental entities. Lastly, establishing causality is intricate, often leading to the misconception that these offenses are victimless (Bisschop & Vande Walle, 2013). Efforts to attribute responsibility in the victim-offender dynamic are thwarted by tactics of denial and a lack of accountability (Natali, 2015). Strategies of denial include refuting the existence of an issue (Cohen, 2001) and shifting blame or causing confusion among victims (e.g., the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and Dawn dish soap/duck campaign; Williams, 1996), impeding progress in addressing environmental victimization (Natali, 2015). Furthermore, despite challenges in establishing direct causation between environmental perpetrators and victims, the use of neutralization techniques by corporations may exacerbate the lack of financial resources faced by residents in areas such as Urban Heat Islands. There may be a lack of upward mobility for communities and oppression by corporations and the government, as these entities avoid culpability (Brown, 2013; Lynch & Barrett, 2015).

While environmental victimization sheds light on possible intentional harm inflicted on communities, spatial distribution of air quality and pollution is an important concept within the realm of environmental justice. The exploration of the social dispersion of air and the variations in air quality across regions with diverse demographic compositions have been examined. For instance, an examination of the ‘dumping in Dixie’ theory, which assessed acute and chronic air pollution emissions, uncovered fluctuating emission distribution patterns that disproportionately impact Black communities under certain conditions (Bullard, 1994; Cutter & Soleck, 1996). Previous research has underscored the significance of comprehending historical trends in urban, social, and industrial developments and their correlation with pollution, including the urban island heat effect highlighted in this report.

The effects of environmental victimization, including issues, such as poor air quality and the proliferation of Urban Heat Islands, are increasingly seen as potential outcomes of environmental racism. Communities that are susceptible to environmental victimization and racism, often are inhabited by racial minorities, and face heightened exposure to environmental hazards due to the deliberate siting of polluting facilities like incinerators and landfills (Bullard, 1993; 2020). Such actions not only perpetuate economic disparities but also reinforce systemic inequalities, leading to differential impacts on health and well-being (Bullard, 2001). Consequently, understanding and addressing environmental injustices, including the disparities seen in air quality

Communities that are susceptible toenvironmental victimization and racism, often are inhabited by racial minorities, and face heightened exposure to environmental hazards due to the deliberate siting of polluting facilities like incinerators and landfills.

and the occurrence of Urban Heat Islands and housing discrimination, requires an examination of the intersecting factors of race, class, and power within the context of environmental racism.

Environmental racism is the deliberate placement of hazardous facilities, industrial sites, and landfills in communities primarily populated by racial minorities and other vulnerable populations. This practice leads to an uneven distribution of environmental burdens and benefits across racial and socioeconomic identities (Bullard, 1993; Mikati et al., 2018). Historical governmental actions, such as redlining and discriminatory zoning, have either directly contributed to or exacerbated environmental injustice, often placing the burden on low-income and minority communities. This highlights the power dynamics within society’s dominant forces, where governmental and industrial decision-making disproportionately affects vulnerable populations (Bullard, 1993). Zoning and redlining have been subtly used to reinforce authority and perpetuate discriminatory practices (Bullard, 1993). Further, evidence of environmental racism is unmistakable when looking at global warming or climate change, particularly Urban Heat Islands.

One of the primary focuses of environmental justice revolves around residential locational patterns, hazardous waste or industrial sites (current or historically) and its polluting activity in poor or minoritized communities. The occurrence of disproportionate placement of industrial facilities may be attributed to three reasons. First, corporations may engage in taste-based discrimination, wherein decision-making preferences prioritize protecting whites from pollution or maliciously favor harming other groups, such as Black communities. Second, placement of industrial sites may be based on local economic conditions, such as corporations seeking to build on inexpensive land or have access to low-wage labor and transportation networks (Banzhaf et al., 2019; Wolverton, 2009). For example, facilities may want to be near highways or railroads, but these routes may also be where there has been past discriminatory transportation siting (Banzhaf et al., 2019). Finally, government agencies make decisions that affect location placement through the permitting process or incentives (Banzhaf et al., 2019).

During the 1980s, several influential studies illuminated the unequal placement of hazardous waste facilities within neighborhoods inhabited by racial minorities and low-income individuals. Bullard’s (1983) examination of waste dump siting patterns in Houston exposed a concentration of these facilities in predominantly Black neighborhoods, often situated near schools. Similarly, a study conducted by the U.S. General Accounting Office (1983) in EPA’s Region IV, particularly in Warren County, North Carolina, revealed that 75% of communities hosting off-site waste landfills were predominantly Black and low-income compared to surrounding areas. Greenberg and

Anderson (1984) also identified racial disparities in New Jersey’s hazardous waste site siting. Additionally, Gould’s (1986) nationwide investigation into toxic waste production and zip codes revealed that areas with the lowest household incomes tended to experience higher levels of toxic waste production.

There are three key psychosocial pathways to poor health associated with environmental injustice (Muller & Camargo, 2023). Firstly, there is trauma, with an emphasis on how living in environments with elevated air pollution levels can be deeply distressing. The constant awareness of exposure to harmful pollutants not only instills fear for personal health but also generates stress and anxiety regarding the well-being of family and community members (Dory et al., 2017). This ongoing trauma is intensified by feelings of helplessness and a lack of support from authorities, such as state environmental agencies or corporations who have the means to intervene and alleviate the issues of air pollution, potentially leading to long-term mental health challenges. Further, research indicates that pollutants can affect the brain and increased exposure to air pollution may be linked to increased risk for mental health problems (Carrington, 2021; Weir, 2012).

Secondly, uncertainty and powerlessness may exacerbate the trauma experienced by affected communities. Uncertainty arises from insufficient and obscure information about environmental health risks that fuels chronic stress, as communities struggle to access vital knowledge about their exposure to pollution. Furthermore, the exclusion of these communities from health-related decision-making processes creates a sense of powerlessness and frustration (Malin, 2020). Despite advocacy efforts, the lack of influence over one’s circumstances can perpetuate feelings of hopelessness and exhaustion.

Lastly, the experience of injustice, particularly environmental injustice and its manifestation in environmental racism may contribute to psychological issues. For example, this form of social injustice disproportionately exposes marginalized populations, such as ethnic minorities and those living in poverty, to environmental hazards. Structural racism and classism force certain communities to reside in areas with heightened pollution levels, perpetuating systemic inequalities (Washington, 2020). The awareness of being systematically exposed to pollution due to factors beyond individual control amplifies the negative health impacts of air pollution, linking environmental injustice to mental ill-health. However, despite its significance, there remains a gap in research concerning this psychosocial pathway, highlighting the need for further investigation to fully comprehend the relationship between air pollution and health within the context of environmental injustice (Muller & Camargo, 2023).

The psychosocial pathways to poor health associated with environmental injustice provide critical insights into the challenges faced by communities residing in Urban Heat Islands. The trauma, uncertainty, and powerlessness experienced by individuals living in environments with elevated air pollution levels highlight the complex interplay between environmental factors and mental well-being. Moreover, the recognition of environmental injustice, particularly in the form of environmental racism, underscores the systemic inequalities that disproportionately affect marginalized populations, particularly Black communities in urban areas.

The historical legacy of redlining, discriminatory lending practices, and systemic disinvestment in predominantly Black neighborhoods has perpetuated structural inequalities and exacerbated vulnerabilities to Urban Heat Islands in Black communities. Redlining, a discriminatory housing policy practiced in the United States during the mid20th century, systematically excluded Black and low-income communities from access to housing loans and investment opportunities (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023).

Neighborhoods inhabited by Black residents were often designated as “hazardous” or “definitely declining” and delineated in red on housing maps, hence the term “redlining,” while predominantly white neighborhoods were labeled as “best” or “still desirable” (Gerken et al., 2023). This discriminatory practice not only denied financial resources to Black communities but also facilitated urban development patterns that perpetuated environmental injustices. Highways and urban renewal programs, often facilitated by federal policies, further divided Black neighborhoods, leading to increased pollution, decreased green space, and higher risks of UHI effects (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023). Today, these redlined neighborhoods exhibit compromised air quality, limited green space, and heightened vulnerability to extreme heat events, exacerbating health disparities and increasing susceptibility to climate-related health impacts (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023). The disproportionate exposure of communities of color and lowincome communities to UHI effects can be attributed to systemic racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and residential segregation (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023). These communities often experience higher levels of heat exposure due to the lack of tree canopy and prevalence of impervious surfaces, such as roads and sidewalks, which inhibit heat dissipation and amplify warming (Hoffman, Shandas, & Pendleton, 2020).

Research indicates that neighborhoods housing Black, Asian, and Hispanic individuals exhibit higher rates of land-cover patterns associated with greater heat-related risks compared to predominantly white neighborhoods (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023).

The disparities in exposure to Heat-Risk Related Land Cover (HRRLC) conditions among racial and ethnic groups underscore the pervasive influence of systemic inequities and residential segregation on environmental outcomes (Jesdale, Morello-Frosch, & Cushing, 2013). Black people are 52 percent more likely to reside in communities with HRRLC conditions compared to white people (Lu et al., 2021). HRRLC conditions intensify with increasing levels of metropolitan area–level segregation, indicating the compounding effects of racial and ethnic disparities and residential segregation on heat exposure. Disparities in access to cooling technologies, such as air conditioning, exacerbate the vulnerability of communities of color and low-income communities to heat-related health complications (O’Neill, 2005). Black people face higher rates of heat-related mortality compared to white people, partly due to disparities in access to central air conditioning (O’Neill, 2005). The compounding effects of urbanization, demographic shifts, and climate change projections underscore the urgency of addressing heat-related disparities and advancing environmental justice initiatives (Hsu et al., 2021). Despite adjustments for homeownership and household poverty, the relationship between high-risk heat and segregation persists, emphasizing the enduring influence of systemic racism and

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

residential segregation on environmental inequalities (Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023). Redlining and systemic discrimination has entrenched environmental injustices and exacerbated vulnerabilities to UHI effects among Black communities and other marginalized groups.

Approximately half of all Black individuals in the United States reside in 11 southeastern states where exposure to extreme heat, hurricanes, and flooding is notably high (Stewart, 2023). Within these states, Black communities are 1.4 times more likely than the overall population to be exposed to extreme heat conditions, underscoring the disproportionate burden faced by marginalized communities (Stewart, 2023). The impacts of extreme heat are unevenly distributed and disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities, exacerbating preexisting disparities in health, housing, income, and occupational safety. Many workers in heat-exposed sectors such as agriculture and construction earn wages below the median income and may lack the financial resources to seek medical attention or afford adequate cooling measures during heatwaves (U.S. Joint Economic Committee, 2023). Furthermore, insecure immigration status and language barriers among agricultural workers can exacerbate vulnerability to dangerous heat exposure, with over 40% estimated to lack legal status and 71% reporting limited English proficiency (Lu et al., 2021).

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

Disparities in access to quality housing amplify heat-related risks, particularly for lowincome rural residents living in substandard manufactured homes lacking insulation and adequate cooling systems (Committee, 2023). These disparities underscore the urgent need for comprehensive interventions to address the economic and social impacts of UHIs on Black communities, mitigate heat-related vulnerabilities, and promote environmental justice.

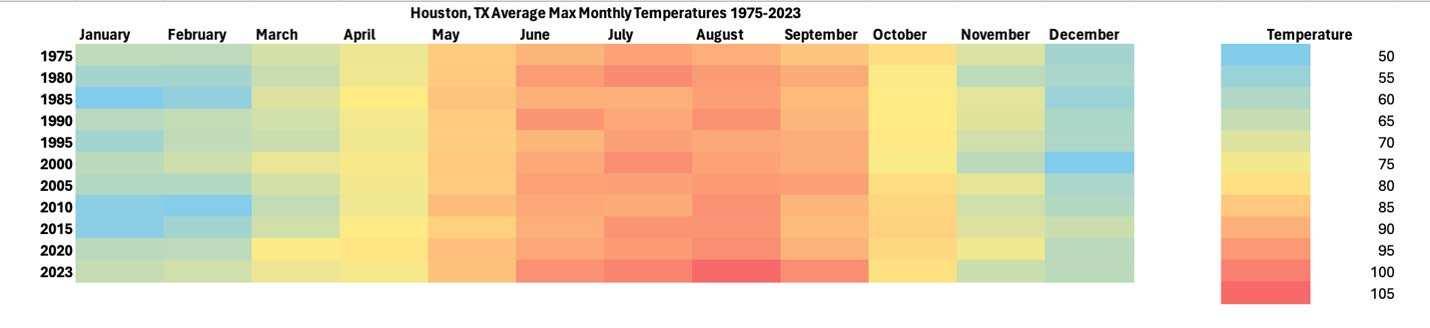

Source: Historical weather data for heat maps comes from Weather Underground (2024)

Chicago exhibits diffused zones of heat intensity, with UHI index values dispersed across the city rather than concentrated in a central core (“Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021). The city’s partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) empowers citizen scientists to map urban heat islands, highlighting the pervasive nature of heat disparities and their impact on health and environmental equity (Blue, 2023). Racial disparities in access to green spaces exacerbate health inequities, with marginalized communities facing limited access to parks and recreational areas (Shukla, 2020). Studies reveal that urban green spaces are larger and more accessible in wealthier and predominantly white neighborhoods, perpetuating environmental injustices (Trust for Public Lands, 2019).

Chicago’s vulnerability assessment of extreme heat events informed the development of a comprehensive Climate Change Action Plan, prioritizing adaptation strategies to mitigate heat-related risks (“Chicago, IL Uses Green Infrastructure to Reduce Extreme Heat: Case Studies: ERIT: Environmental Resilience Institute: Indiana University,” 2021). The city’s initiatives include promoting emergency response procedures and integrating heat island reduction strategies into long-term planning efforts. To address disparities in access to green spaces, Chicago targets urban heat island “hot spots” with heat reduction strategies such as green infrastructure and reflective roofing

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

(“Chicago, IL Uses Green Infrastructure to Reduce Extreme Heat: Case Studies: ERIT: Environmental Resilience Institute: Indiana University,” 2021). The city incentivizes the adoption of green infrastructure through expedited permitting processes and grants for small projects, promoting resilience and sustainability across diverse communities. Chicago highlights the importance of addressing urban heat islands and promoting equitable access to green spaces to mitigate health inequities and foster environmental resilience. By prioritizing community engagement, education, and strategic partnerships, Chicago can advance environmental justice and cultivate a sustainable urban environment for all residents.

Source: Historical weather data for heat maps comes from Weather Underground (2024)

Houston, Texas, faces formidable challenges related to Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) and the intersection of environmental hazards with socioeconomic disparities (“Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021). The sprawling urban landscape of Houston presents unique complexities in addressing heat vulnerabilities and promoting climate resilience across diverse communities. In Houston, high UHI index values are not localized in a central core but are dispersed across a vast developed land area, intensifying heat exposure for residents (“Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021). The city’s unique geographical and demographic characteristics contribute to disparate heat impacts, exacerbating inequalities in access to cooling resources and resilience measures.

In 2021, 73 percent of Houston residents experienced temperatures 8 degrees Fahrenheit higher than surrounding suburban areas, highlighting the pervasive nature of heat disparities (“Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021). Residents in eastern Harris County neighborhoods, such as Kashmere Gardens and Denver Harbor, faced heightened vulnerability to heat stress and exhibited lower levels of air conditioning access compared to wealthier neighborhoods like the Heights and Bellaire (Bruess, 2023). A report by Harris County Public Health underscores the severe inequality in heat vulnerability, with nearly 23,000 housing units in the Houston metro area lacking any form of air conditioning (Sledge, 2023).

On July 26, 2023, the City of Houston unveiled the nation’s first-ever Urban Heat Island Model City at the Green Building Resource Center (Castillo, 2023). Developed by TX/ RX Labs using cutting-edge technology, the Urban Heat Island Model City and Toolkit offer invaluable insights for sustainable urban planning and climate resilience strategies (Stelzer, 2023). Comprising 68 3D-printed buildings with 19 different designs, along with accessory structures and trees, the model provides a holistic representation of the urban landscape with tangible solutions to issues such as lack of green space and economic inequity (Stelzer, 2023). This innovative tool enables policymakers, urban planners, and community stakeholders to visualize and address the complex interplay of urban heat dynamics and socioeconomic disparities in Houston. Houston underscores the imperative of radical and proactive measures to address UHIs and mitigate heat vulnerabilities, particularly among marginalized communities. By leveraging innovative technologies and fostering community engagement, cities can develop inclusive and sustainable urban environments that promote equity and resilience in the face of climate change.

FL

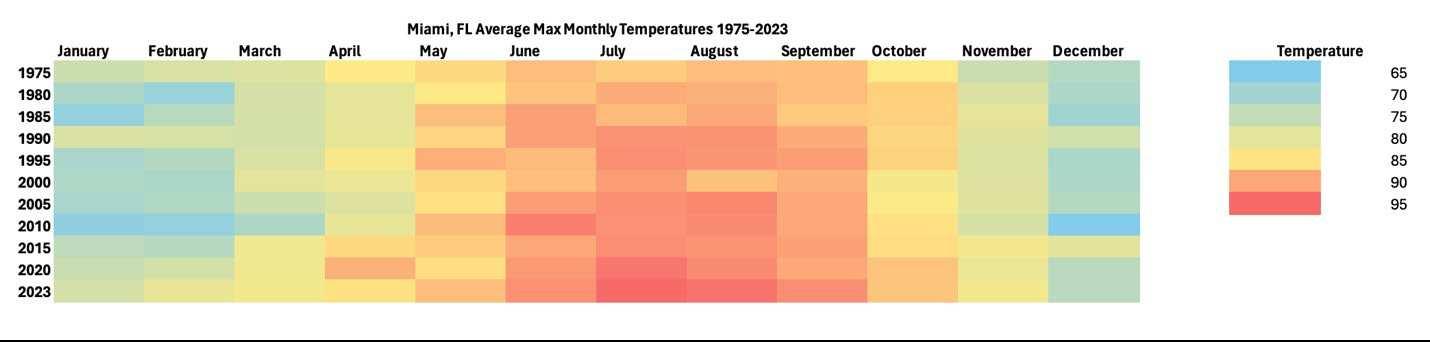

Source: Historical weather

Miami, Florida, grapples with the challenges posed by Urban Heat Islands (UHIs), exacerbated by dense urbanization and low-albedo water bodies along the coast. Temperatures are intensified in densely packed urban areas like Brickell and downtown, where the absence of green spaces exacerbates heat retention (Rivero, 2023). Coastal cities like Miami face additional challenges, with low-albedo water bodies contributing to elevated UHI index values (“Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021).

The Miami-Dade County government has initiated efforts to raise awareness and mitigate heat-related issues through community education campaigns and urban greening initiatives (“Greening and Sector Jobs,” 2022). These initiatives aim to foster a deeper understanding of the role of urban tree canopy in mitigating extreme heat, promoting health, and advancing environmental resilience. Miami-Dade’s community education campaign emphasizes the historical legacy of redlining in shaping heat

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

islands and tree canopy distribution, highlighting the connections between social equity, environmental justice, and urban greening (Rivero, 2023). By engaging residents in dialogue and education, the county seeks to overcome resistance to urban greening initiatives by emphasizing the multiple benefits, including improved health outcomes and energy savings.

Community engagement strategies, such as community walks and partnerships with Miami-Dade County Public Schools, aim to involve youth in urban greening efforts and foster interest in environmental stewardship and STEM-related career pathways (“Greening and Sector Jobs,” 2022). Additionally, partnerships with workforce development organizations facilitate the coordination of talent pipelines for urban greening jobs, promoting job opportunities and economic resilience within the community.

Miami underscores the importance of collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches to addressing the complex challenges posed by UHIs and environmental inequities. By prioritizing community engagement, education, and strategic partnerships, Miami-Dade County can foster resilience, promote environmental justice, and cultivate a sustainable urban environment for present and future generations.

NEWARK, NJ2

3

2 Newark, New Jersey has a comparison city of Hackensack due to the nature of the where the cities are placed in the Northeastern region of the United States. Similar temperatures may be seen; however, Newark is urban and Hackensack is suburban.

3 Heat maps were created using historical weather data. Data used were the average monthly maximum temperatures. from 1975 through 2023. All data points were placed into an excel file and then formatted to express the temperature changes. Blue and green represent cooler temperatures, with orange and red representing warmer temperatures.

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

Newark, New Jersey, has grappled with rising temperatures, showing an average of 7.7 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than surrounding areas (Urban Heat Islands | Climate Central,” 2021). The confluence of high population density, extensive impervious surfaces, and towering buildings intensifies heat retention, posing significant health risks and exacerbating social disparities. According to Climate Central, of the 705,936 residents in Newark as per the 2020 U.S. census, 198,512 reside in census tracts experiencing 8 degrees Fahrenheit or more of Urban Heat Island effect.

Newark has turned to community organizing and nonprofit partnerships to address UHIs and promote equitable access to cooling resources. Initiatives such as the i-Tree Tool by the Office of Sustainability prioritize underserved neighborhoods for tree planting, aiming to mitigate heat islands and enhance urban greenery (US EPA, 2019). In response to escalating heat risks, Congresswoman Bonnie Watson Coleman (NJ-12) reintroduced the “H.R.4314 - Stay Cool Act” in June 2023, aimed at bolstering federal response to heat emergencies (Watson Coleman, 2023a). The proposed legislation addresses the immediate impacts of extreme heat, particularly in marginalized communities disproportionately affected by environmental injustices.

By adopting proactive measures and policy interventions, cities can mitigate the impacts of climate change while fostering equity and resilience among vulnerable populations. Newark’s commitment to environmental justice and sustainable urban development sets a precedent for cities grappling with the intersection of environmental factors and social vulnerabilities.

Source: Historical weather data for heat maps comes from Weather Underground (2024)

Recent studies have underscored the correlation between redlining and environmental variables such as impervious surfaces, tree coverage, and UHIs (Hoffman et al., 2020; Nardone et al., 2021). The evidence suggests that historically redlined neighborhoods experience higher land surface temperatures (LST) compared to non-redlined areas (Wilson, 2020). In New Orleans, the practice of redlining contributed to the spatial

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

distribution of environmental disparities, with predominantly African American neighborhoods facing disproportionate impacts (Woodward, 2019). New Orleans’ Councilmember Helena Moreno’s initiative in September 2023 allocated $300,000 to conduct a comprehensive urban heat analysis in partnership with the City’s Resilience and Sustainability Office and the City Department of Health (Moreno, 2023). The initiative responds to the alarming statistics revealing that over 70 percent of New Orleanians live in UHIs, exacerbating the city’s vulnerability to extreme heat events. The redlined maps of New Orleans delineated racially segregated neighborhoods, where predominantly African American communities faced disinvestment and neglect (Huang & Sehgal, 2022). The allocation of resources and infrastructure development favored affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods such as the Garden District, perpetuating racial disparities in access to green spaces and cooling amenities. New Orleans highlights the urgent need for intersectional approaches to address environmental injustices and mitigate the impacts of UHIs. Policy interventions must confront the historical legacies of redlining and systemic racism while promoting equitable access to urban green spaces, cooling infrastructure, and resilience measures. By fostering community engagement and interdisciplinary collaborations, cities can strive towards environmental justice and create inclusive, sustainable urban environments for all residents.

As urbanization accelerates and the impacts of climate change become increasingly pronounced, combating Urban Heat Islands is a critical imperative for fostering sustainable and equitable urban environments. In addressing UHIs, it is imperative to recognize the intersectionality between environmental degradation, social inequity, and economic disparities within Black communities disproportionately affected by heatrelated risks. The following policy recommendations are designed to tackle Urban Heat Islands through a lens of climate equity, providing pathways for Black communities to engage in sustainable urban development while safeguarding their well-being and promoting inclusive growth. By embracing these recommendations, policymakers, urban planners, and community stakeholders can forge a path toward more resilient, equitable, and sustainable communities.

1. Equitable Urban Green Initiatives: Legislators should implement policies that prioritize the equitable distribution of green spaces, tree canopy coverage, and cooling infrastructure in historically marginalized communities, including Black neighborhoods. This can be achieved through targeted investment in urban forestry programs, community gardens, and green infrastructure projects aimed at reducing Urban Heat Islands while promoting economic opportunities and environmental justice.

2. Community-Based Heat Resilience Programs: Local advocates can develop community-driven heat resilience programs that empower Black communities to address UHI effects and enhance their capacity to address extreme heat events. These programs should include initiatives such as heat emergency response plans, community cooling centers, and workforce development programs focused on green jobs and sustainable urban development.

3. Financial Incentives for Sustainable Development: Legislators should provide financial incentives to homeowners in historical UHI impacted communities who implement sustainable building practices, such as cool roofs, permeable pavements, and green building designs.

4. Equitable Zoning Regulations: Local legislature should create zoning regulations and land-use policies that prioritize the protection and enhancement of natural landscapes, green spaces, and tree canopy cover in urban areas, particularly in communities disproportionately impacted by UHIs. This includes zoning protections to prevent the displacement of residents due to gentrification and ensure affordable housing options amidst urban development efforts.

5. Climate Equity Assessments and Planning: Developers and city planners should integrate climate equity assessments into urban planning processes to identify and address disparities in exposure to UHIs and heat-related risks among Black communities. This involves conducting comprehensive vulnerability assessments, engaging stakeholders from diverse backgrounds, and developing inclusive climate action plans that prioritize the needs and voices of marginalized populations.

Addressing Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) requires a holistic approach that recognizes the intersectionality between environmental degradation, social inequity, and economic disparities, particularly within Black communities. The historical legacy of discriminatory practices such as redlining has perpetuated structural inequalities and exacerbated vulnerabilities to UHI effects among marginalized groups. Environmental victimization, rooted in systemic racism and residential segregation, continues to disproportionately expose communities of color to environmental hazards, amplifying the impacts of UHIs. To combat these challenges, policymakers, urban planners, and community stakeholders must prioritize climate equity and promote inclusive growth through targeted interventions. Equitable urban green initiatives, community-based heat resilience programs, financial incentives for sustainable development, equitable zoning regulations, and climate equity assessments are essential components of a comprehensive strategy to mitigate the impacts of UHIs and foster resilient, equitable, and sustainable communities.

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

2019 Annual Report. (2019). Retrieved March 21, 2024, from Trust for Public Land website: https://www.tpl.org/2019-annual-report

Banzhaf, S., Ma, L., & Timmins, C. (2019). Environmental justice: The economics of race, place, and pollution. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(1), 185-208. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.33.1.185

Bird, M. (2022, July 7). The Temperature of Disinvestment: Examining Urban Heat Islands and Historically Redlined Communities» NCRC. Retrieved March 5, 2024, from https://ncrc.org/the-temperature-of-disinvestment-examining-urban-heat-islands-andhistorically-redlined-communities/

Bisschop, L., & Vande Walle, G. (2013). Environmental victimisation and conflict resolution: A case study of e-waste. In R. Walters, D. Westerhuis, & T. Wyatt (Eds)., Emerging issues in green criminology. Exploring power, justice and harm (pp. 34-54). Palgrave Macmillan.

Blue, C. of. (2023, August 9). FRESH: As Chicago Broils, Citizens and Scientists Study “Heat Island” Effect. Retrieved March 21, 2024, from Great Lakes Now website: https://www.greatlakesnow.org/2023/08/fresh-chicago-broils-citizens-scientists-studyheat-island-effect/

Brown, P. (2013). Toxic exposures: Contested illnesses and the environmental health movement. Columbia University Press.

Bullard, R. D. (1983). Solid waste sites and the black Houston community. Sociological Inquiry, 53(2-3), 273-288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1983.tb00037.x

Bullard, R. D. (1993). Anatomy of environmental racism and the environmental justice movement. In R. D. Bullard (Ed.)., Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots (pp. 15-40). South End Press.

Bullard, R. D. (1994). Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality (2nd ed.). Westview Press. Bullard, R. D. (2001). Decision making. In L. Westra & B. E. Lawson (Eds.), Faces of environmental racism: Confronting issues of global justice (2nd) (pp. 3-28). Rowman & Littlefield.

Bullard, R. D. (2020). Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality (3rd ed.). Routledge. Carrington, D. (2021, August 27). Air pollution linked to more severe mental illness—study. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/aug/27/air-pollution-linked-to-more-severe-mental-illness-study

Cohen, S. (2001). States of denial: Knowing about atrocities and suffering. Polity Press.

Committee, U. S. J. E. (2023, August 10). The Mounting Costs of Extreme Heat—The Mounting Costs of Extreme Heat - United States Joint Economic Committee. Retrieved from www.jec.senate.gov website: https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/ democrats/2023/8/the-mounting-costs-of-extreme-heat

Cutter, S. L., & Solecki, W. D. (1996). Setting environmental justice in space and place: Acute and chronic airborne toxic releases in southeastern United States. Urban Geography, 17(5), 380-399.

Dory, G., Qiu, Z., Qiu, C. M., Fu, M.R., & Ryan, C.E. (2017). A phenomenological understanding of residents’ emotional distress of living in an environmental justice community. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2016.1269450

Gerken, M., Batko, S., Fallon, K., Fernandez, E., Williams, A., & Chen, B. (2023). Assessing the Legacies of Historical Redlining Correlations with Measures of Modern Housing Instability. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/ Addressing%20the%20Legacies%20of%20Historical%20Redlining.pdf

Gouldson, A. (2006). Do firms adopt lower standards in poorer areas? Corporate social responsibility and environmental justice in the EU and the US. Area, 38(4), 402-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2006.00702.x Greenberg, M., & Anderson, R. F. (1984). Hazardous waste sites: The credibility gap. Routledge. Hoffman, J. S., Shandas, V., & Pendleton, N. (2020). The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to IntraUrban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas. Climate, 8(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010012

Hsu, A., Sheriff, G., Chakraborty, T., & Manya, D. (2021). Publisher Correction: Disproportionate exposure to Urban Heat Island intensity across major US cities. Nature Communications, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23972-6

Jesdale, B. M., Morello-Frosch, R., & Cushing, L. (2013). The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk–Related Land Cover in Relation to Residential Segregation. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(7), 811–817. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205919

CPAR | Burning Issues: Heat Islands, Environmental Victimization, and Economic Disparities in Black Communities

Lu, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., Yang, Y., Sullivan, W. C., Xu, W., … Jiang, B. (2021). Green spaces mitigate racial disparity of health: A higher ratio of green spaces indicates a lower racial disparity in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in the USA. Environment International, 152, 106465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106465

Lynch, M. J., & Barrett, K. L. (2015). Death matters: Victimization by particle matter from coal fired power plants in the US, a green criminological view. Critical Criminology, 23, 219-234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-015-9266-7

Malin, S. A. (2020). Depressed democracy, environmental injustice: Exploring the negative mental health implications of unconventional oil and gas production in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101720

Mikati, I., Benson, A.F., Luben, T. J., Sacks, J. D., & Richmond-Bryant, J. (2018). Disparities in distribution of particulate matter emission sources by race and poverty status. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 480-485. https://doi.org/10.2105/ AJPH.2017.304297

Morello-Frosch, R., & Obasogie, O. K. (2023). The Climate Gap and the Color Line—Racial Health Inequities and Climate Change. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(10), 943–949. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsb2213250

Muller, M., & Camargo, A. (2023). The mental distress of environmental injustice. Urban Health Council. https://www.urbanhealthcouncil.com/reports-playbooks/mental-distress-of-environmental-injustice#:~:text=After%20 an%20air%20pollution%20or,insomnia%2C%20or%20even%20chronic%20fatigue

Natali, L. (2015). A critical gaze on environmental victimization. In R. Solund (Ed.), Green harms and crimes: Critical criminology in a changing world (pp. 63-78). Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Neill, M. S. (2005). Disparities by Race in Heat-Related Mortality in Four US Cities: The Role of Air Conditioning Prevalence. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 82(2), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti043

UCAR. (2021). Urban Heat Islands | UCAR Center for Science Education. Retrieved from scied.ucar.edu website: https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/climate-change-impacts/urban-heat-islands

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, June 17). Heat Island Impacts. Retrieved from US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/heat-island-impacts

Urban Heat Islands. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.heat.gov website: https://www.heat.gov/pages/urban-heat-islands

US EPA, O. (2014, June 17). Learn About Heat Islands. Retrieved from www.epa.gov website: https://www.epa.gov/ heatislands/learn-about-heat-islands#heat-islands

US EPA, O. (2015b, December 29). Urbanization—Temperature. Retrieved March 5, 2024, from www.epa.gov website: https://www.epa.gov/caddis/urbanization-temperature

US EPA. (2015a, October 1). Reduce Urban Heat Island Effect. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/reduceurban-heat-island-effect#:~:text=%22Urban%20heat%20islands%22%20occur%20when

US General Accounting Office. (1983). Siting of hazardous waste landfills and their correlation with the racial and socioeconomic status of surrounding communities. U.S. Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/products/ rced-83-168

Walker, G. (2012). Environmental justice: Concepts, evidence and politics. Routledge. Washington, H. A. (2020, May 19). How environmental racism fuels pandemics. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/ d41586-020-01453-y

Watson Coleman, B. Stay Cool Act., Pub. L. No. H.R.4314 (2023a). Weather Underground. (2024). https://www.wunderground.com/ Weir, K. (2012). Smog in our brains: Researchers are identifying starting connections between air pollution and decreased cognition and well-being. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/07-08/smog Williams, C. (1996). An environmental victimology. Social Justice, 23, 16-40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29766973 Wolverton, A. (2009). Effects of Socioeconomic and Input-related factors on polluting plants’ location decisions. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 2-35. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2083