The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

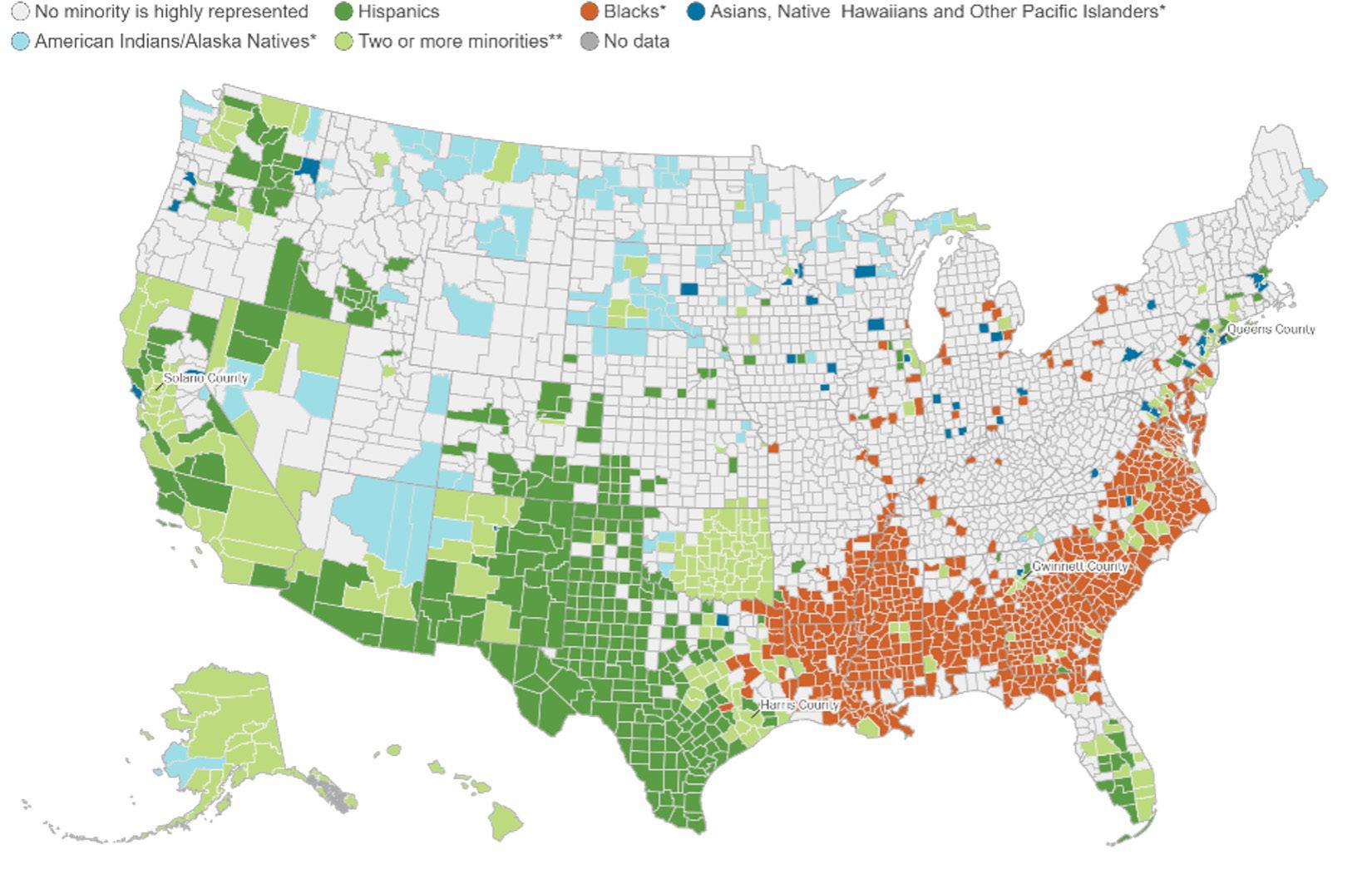

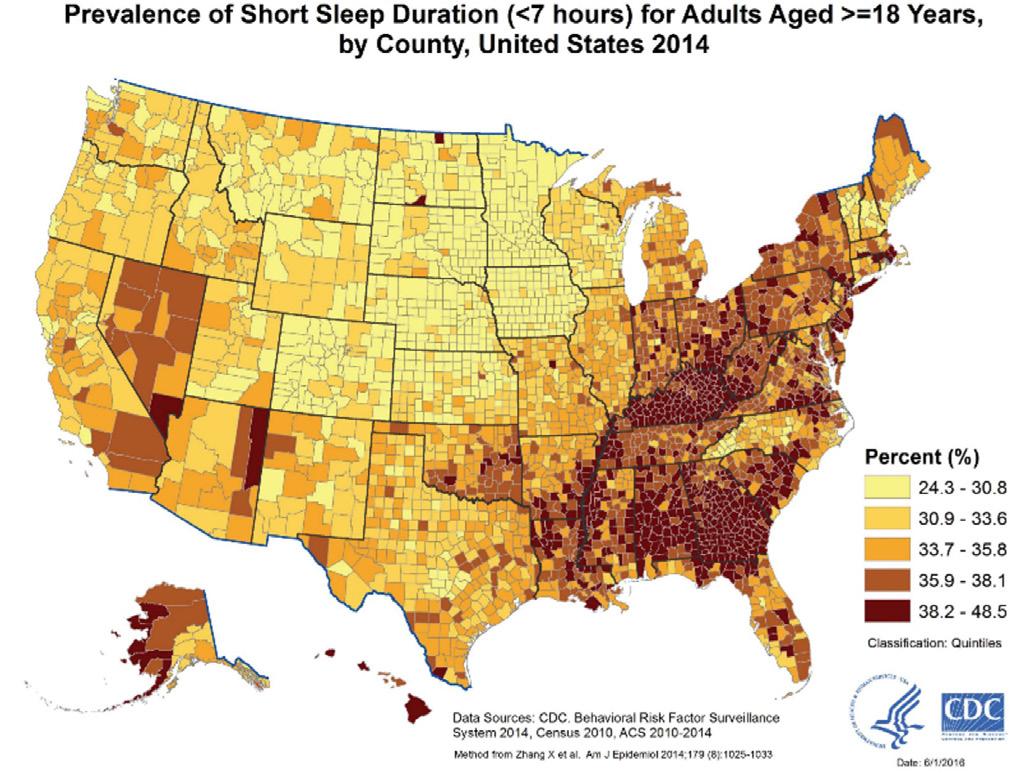

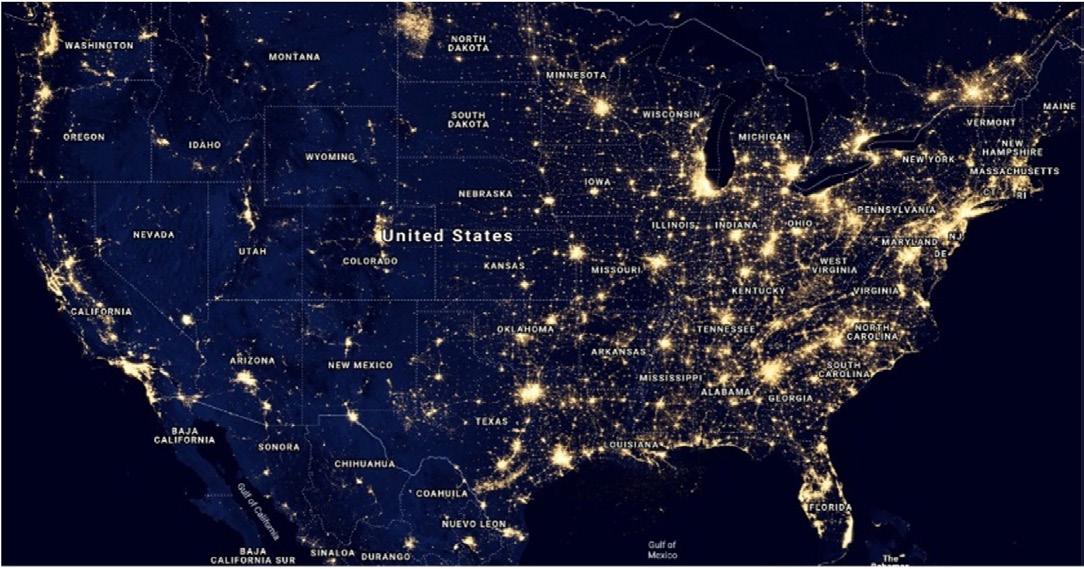

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a comprehensive sleep report detailing the sleeping habits of Americans across the nation by age, race, and gender. The CDC recommends for adults at least 7 hours of sleep with no more than one interruption a night and taking 30 minutes or less to fall asleep. The report found that 35% of Americans do not meet these requirements. An analysis of a sleep map and racial demographic map reveals a correlative relationship between sleep quality and race (Frey, 2019).

Source: CDC - Data and Statistics—Sleep and Sleep Disorders. (2021, September 13)

Source: Frey, W. H. (2019, August 29). Six maps that reveal America’s expanding racial diversity. Brookings

CPAR | The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

The findings showed that Black Americans slept less, were interrupted more times during sleep, took longer to fall sleep and spent less time in deep sleep.1 The CDC report further legitimized a growing body of research from sleep scientists about the racial disparities of sleep, and its detrimental impact on the overall health outcomes of Black Americans. More recent studies have expanded on the sleep gap between Black and White Americans with evidence showing that disparities begin as early as pre-school, exist through adolescence, and continue into adulthood (Bonuck et al., 2016). Across each stage of development, the impact of poor sleep compound and worsen overtime. Black Americans are 24.1% more likely than White Americans to obtain less than 6 hours of sleep a night, 5.4% more likely to suffer from sleep apnea, 2.5% more likely to suffer from insomnia and 7.4% more likely to suffer from excessive daytime sleepiness (Perez, 2021).

Sleep expert Dr. Azizi Seixas describes sleep as “the most primordial human activity, [and] we can’t do without it” (Perez, 2021). One of the primary functions of sleep is recovery. Throughout a day the human body constantly manages a variety of tasks from fighting off viruses/bacteria, regulating stress levels and/or meeting the physical requirements that our lives demand. Sleep plays a critical role in helping our bodies recover from the day and prepare for the next. When we sleep our bodies undergo a recovery process and a maintenance cycle.

1 Deep sleep is the third stage of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep. Deep sleep is also known as slow-wave sleep. This is the stage of sleep where your brain waves are at their slowest.

During sleep our metabolism slows dramatically and the energy conserved in that process becomes available to us in the following day.

Research suggest that getting healthy sleep can produce a daily energy savings of 35% (Schmidt et al., 2017).

As we sleep, brain activity increases in areas that regulate our emotions such as the amygdala (fear).

When sleep deprived, the amygdala is more likely to overreact to situations, increasing or worsening the likelihood of anxiety disorders (Nunez et. al, 2020).

One function of healthy cells is to take up glucose and process it for body use.

Sleep is a critical part of maintaining healthy cells, which in turn protects them from developing insulin resistance (Lucassen et al., 2012).

As we sleep our bodies undergo multiple processes that encourage healing and growth such as muscle repair, tissue growth, and vital hormone releases (Nunez et. al., 2020).

Sleep allows the neuron and nerve cells in our brain to reorganize themselves. This process is crucial to learning, concentration, focus, and decision-making.

Sleep is also vital to our memory as it helps our brain convert short-term memories into long-term memory and clears out unneeded information that would clutter our nervous system (Nunez et. al., 2020).

HEART HEALTH:

During sleep our blood pressure drops about 10-20% to accommodate the lack of physical/mental activity.

This process—nocturnal dipping—helps to regulate our overall blood pressure and plays a crucial role in the maintenance of cardiovascular health (Calhoun and Harding, 2010).

Sleep affects weight by controlling hormones such as ghrelin (appetite) and leptin (fullness).

Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin and suppresses leptin.

This imbalance can lead to increased hunger causing one to eat more and gain weight (Cedernaes et al., 2018).

Research has shown that a lack of sleep can inhibit the immune system, making us more susceptible to harmful germs.

When we sleep our body creates proteins, immune cells, and antibodies that are responsible for fighting off sickness and disease (Asif et al., 2017).

Short-term sleep deprivation2 is manageable and includes symptoms such as memory issues, concentration, increased stress, lack of energy and poor or risky decision-making. Long-term sleep deprivation,3 however is linked to an increased risk of many chronic health issues that can lead to detrimental impacts on an individual’s overall health (Medic et al., 2017). While poor sleep impacts our health in a variety of ways, there are four that are most pertinent to Black Americans: Type-2 Diabetes, sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. Each of these illnesses have an increased presence within the Black community, and collectively account for a third of health-related deaths (CDC, 2018). While there are factors outside of sleep that can lead to the outlined illnesses, lack of sleep has a negative influence on each. Understanding how sleep impacts each illness is crucial to developing the necessary tools that are culturally tailored and relevant to addressing Black sleep health.

The National Diabetes Statistic Report identified that Black Americans are at an increased risk for T2D (CDC, 2018). The factors leading to diabetes include diet and genetics. A study found that receiving less than six hours of sleep increases the risk of T2D (Zizi et al, 2012). Due to the vital role that sleep plays in insulin regulation, a lack of sleep increases unhealthy insulin-resistant cells. An increase in insulin-resistant cells makes it more difficult for individual’s with diabetes to manage their glucose levels (Van Cauter et al., 2018). Sleep deprivation is also linked to an increased level of hunger leading to an individual being more likely to eat “junk food” (high carbs and sugar) (Singh S et al, 2021). Unhealthy weight gain increases the likelihood of obesity impacting diet and further exacerbating T2D. Obesity or unhealthy weight gain is even more prevalent for adolescents and children as they require more sleep than adults do (Miller et al., 2015). The combination of these factors can create a cyclical pattern that compounds over time, worsening overall health outcomes. The diagnosis of T2D is normally exclusively linked to diet and genetics, but sleep health is a contributing factor to combatting T2D both in adolescence and adulthood.

2 Short-term sleep deprivation occurs when one experiences three days of less than seven hours of sleep.

3 Long-term sleep deprivation occurs when one experiences three months or more of less than seven hours of sleep.

its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

While poor sleep impacts our health in a variety of ways, there are four that are most pertinent to Black Americans: Type-2 Diabetes, Sleep Apnea, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea is a sleep disorder where breathing repeatedly stops and starts while a person is sleeping. This disorder is common in Black communities, but it is rarely diagnosed (Dudley and Patel, 2015). The Jackson Heart Study found that 95% of Black people went undiagnosed and untreated (Johnson et al., 2021). Additionally, Black people are associated with a 20% increase in OSA severity and Black children are 4-6 times more likely to suffer from OSA than their White counterparts. The symptoms of OSA include an increased chance of insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep deprivation, and excessive snoring. These symptoms lead to a worse night’s sleep which can further exacerbate OSA, and other health issues related to sleep. One of the strongest risk factors connected to OSA is obesity, with 50% of diagnoses attributed to being overweight (Dudley and Patel, 2015).

The Office of Minority Health (OMH) reported that Black Americans were 30% more likely to die from heart disease than any other race (Heart Disease and African Americans – OMH n.d.). Recent studies link sleep deprivation to an increased chance of suffering from heart disease. Heart disease occurs when plaque builds up in the arteries—this condition is called “atherosclerosis.” A correlation between sleep deprivation and atherosclerosis exists due to chronic inflammation in the body caused by poor sleep (Vallat et al., 2020). Chronic inflammation can trigger the immune system causing it to produce white blood cells that harden around the affected area which narrows the arteries and results in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis paired with a disruption of the body’s regulatory function of nocturnal dipping4 can lead to chronic hypertension. Over time this strains the arteries, hindering its ability to circulate blood throughout the body including the heart. This leads to a higher chance of heart failure in people that report sleeping 7 hours or less. For those that report sleeping less than 6 hours, there is also a 20% increased chance of a heart attack (Daghlas et al., 2019).

Sleep deprivation not only impacts the heart, but also the brain. A stroke is triggered when blood flow to the brain is blocked. OMH found that Black Americans are 50% more likely than their White counterparts to have a stroke and have the highest rate of stroke-related deaths compared to all other races (Stroke and African Americans – OMH, n.d.). The leading cause for strokes is high blood pressure, and sleep deprivation’s negative influence on blood pressure leads to the increased chance of a stroke. Additional causes for strokes include diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and severe sleep apnea.

Poor sleep impacts our health in a variety of ways, but these four account for a third of health-related deaths for Black Americans. Sleep is a fundamental human function and its impact on Black health is critical. Understanding why Black Americans suffer from poor sleep is vital to improving the health outcomes of Black communities.

4 Nocturnal dipping is a natural and necessary physiological function where the heart drops its blood pressure 10-20% at nighttime.

While sleep impacts many aspects of health, the contributors to poor sleep health are often systemic, structural, and external for Black Americans. Research exposes that there are many factors that impact Black sleep health, including historical, socioeconomic, environmental, sleep literacy, racism, and discrimination.

Black Americans have suffered from poor sleep since slavery. In Dr. Joy Degruy’s seminal work, Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome, she details how trauma from slavery and past generations do not exist in vacuums. Instead, trauma is compounded across generations leading to altered behavior patterns in later generations (Leary, 2005). Africans that were enslaved were forced to sleep in unimaginably horrific conditions during the trek to the Americas. Upon arrival they were made to work long hours in unsafe conditions that were not conducive to sleep. When sleep was considered, it was only in the efforts to boost the productivity of the slaves. Historical records note that slaveholders associated the poor sleep and “laziness” of enslaved descendants to their inferiority as a race (Cartwright, 1851).

Louisiana physician Samuel Cartwright associated it with a disease he called dysaesthesia aethiopica — “a disease peculiar to negroes, affecting both mind and body” causing them to be lazy (Cartwright, 1851). This pseudo-scientific belief was held across the slave south and spread across the country, with then President Thomas Jefferson stating that Black people needed less sleep than Whites. Jefferson believed that White people’s ability to stay awake at night was a sign of their superiority and passion to pursue creative and intellectual pursuits (Jefferson, 1853). While Black people lacked the ability nor the will to do so, this belief led to a further worsening of conditions for Black people. Hard work was considered the cure for sleepiness and was often accompanied by a whip. In his memoir, Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Frederick Douglass wrote that “More slaves were whipped for oversleeping than any other fault” (Douglass, 1849). Douglass shared the impact this had on his physical and mental state describing himself as being in a “beast-like state” unable to act towards his freedom. The belief that Black people’s lack of sleep is attributed to disposition rather than historical implications persists today. The trope of the “lazy Black man” is rooted in this pseudoscientific racist ideology created by Samuel Cartwright. It has led to Black people’s fatigue and exhaustion being met with little regard for the obstructive sleep environments or the extreme physical, emotional, and mental stress many find themselves in.

In 2020, 19.5% of Black Americans lived below the poverty line (Statista, 2020). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report that 62.3% of Black people participated in the workforce, just under the national average of 62.9% and comparable with 62.8% of Whites. Amount of work is a contributing factor to sleep loss, but it is not the only issue.

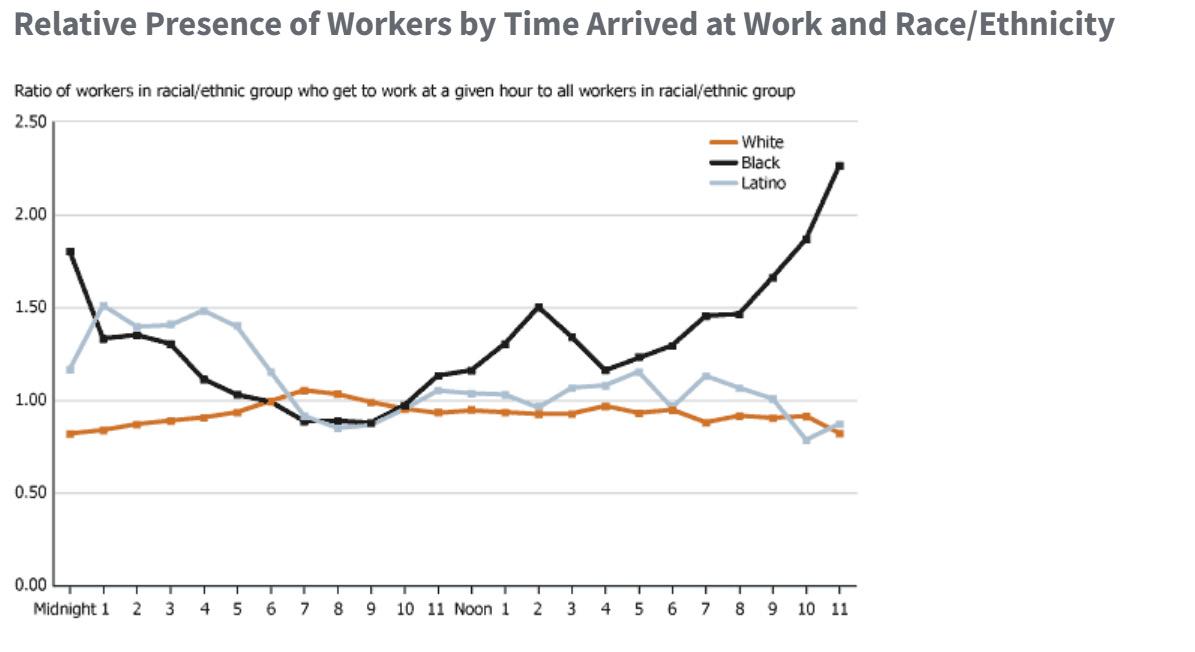

The BLS identified that Black people are about twice as likely to work evening and night hours and twice as likely to have irregular work schedules (BLS Table 7. Workers by Shift Usually Worked and Selected Characteristics, Averages for the Period 2017-2018, n.d.). This is due to the over-representation of Black people in shift work. The inherent irregularity of the hours of shift work is not conducive to creating healthy sleep habits. Irregular work hours disturb the circadian rhythm5 and make it difficult for the body

Source: PRB. (n.d.). A Demographic Profile of U.S. Workers Around the Clock. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/resources/a-demographic-profile-of-u-s-workers-around-the-clock/

to develop a regular day/night schedule necessary for sleep. Evidence suggests that unconscious and conscious bias could play a part in the likelihood of Black people to work irregular hours.

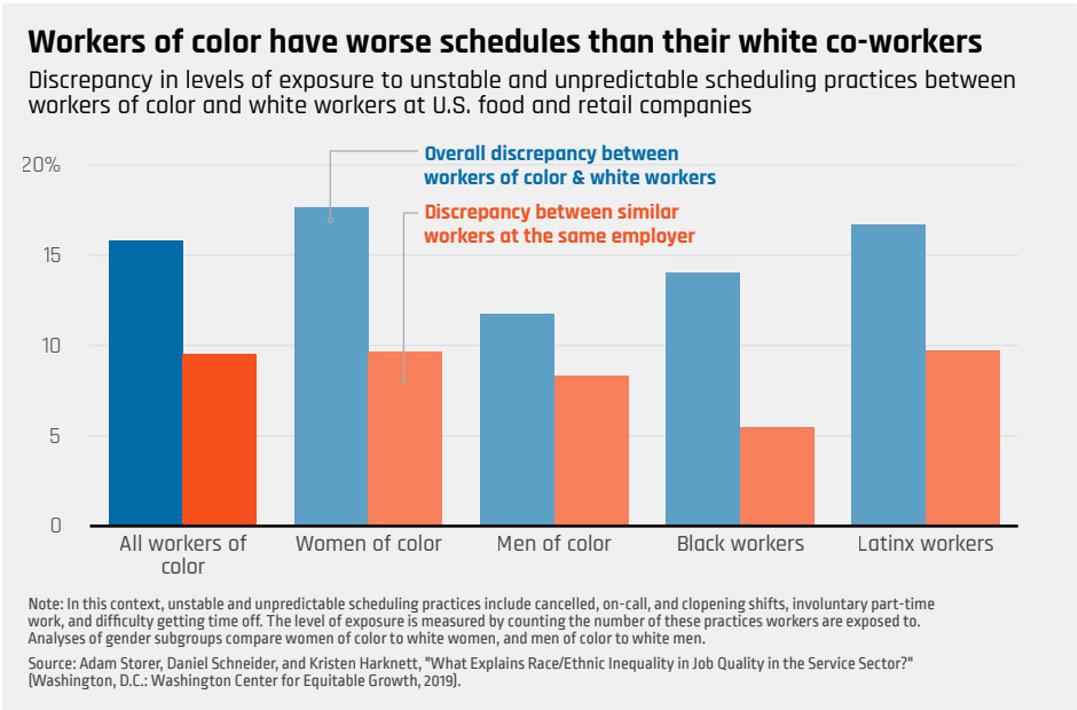

A 2019 research study found that there was a 14% discrepancy in the assignment of shift work between Black and White workers; the study also showed that about 63% of it can be attributed to the differing race of the shift manager and the shift worker (Schneider and Harknett, 2019).

5 Circadian rhythms are 24-hour cycles that are part of the body’s internal clock, running in the background to carry out essential functions and processes. One of the most important and well-known circadian rhythms is the sleepwake cycle.

BLS data demonstrates that across the past decade the only group that has increased their percentage of multiple job holders are Black people (Merling, 2016). BLS reports that 5% of Black workers hold multiple jobs, often due to a need to supplement the poor wages and lack of economic stability that the U.S. labor market offers. Black people are often willing to take additional opportunities to work, deprioritizing sleep in the process. Due to these conditions the current socioeconomic situation creates barriers for Black people to get a healthy night’s rest.

The impact of environmental racism on Black communities is a phenomenon that in recent years has received more attention. Due to a history of housing discrimination, research has identified that Black people live in more environmentally hazardous areas (Christensen et al., 2020). This includes increased exposure to pollution, food deserts, and light & noise pollution. People living in areas with elevated levels of pollution are 60% more likely to have issues with sleep health (Pultarova, 2017). This association is exacerbated by the increased likelihood of Black families living in food deserts restricting their access to healthy food options, negatively impacting their diet, and having a cascading effect on sleep.

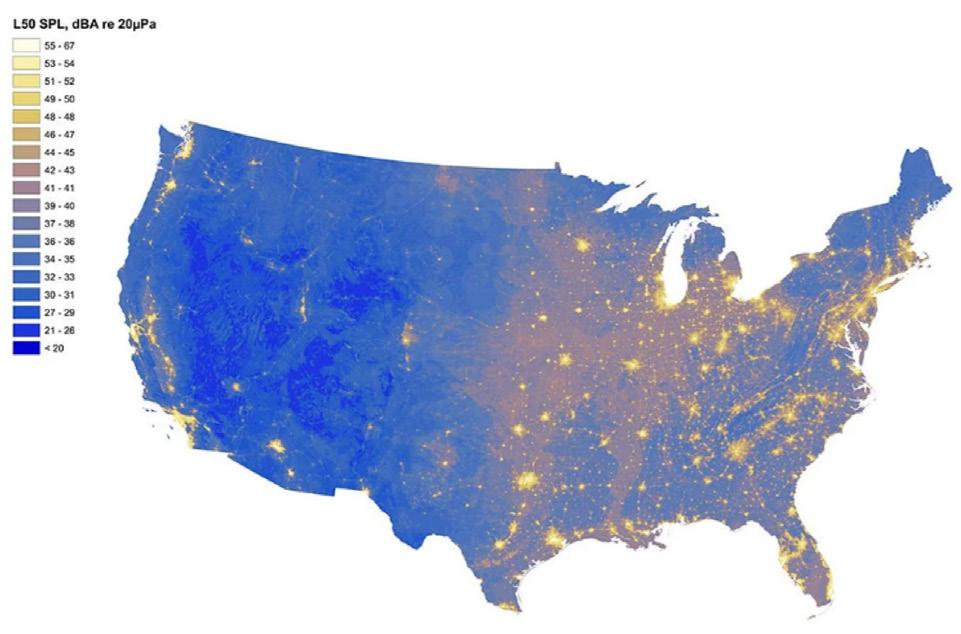

Both food deserts and air pollutions are well known factors that impact sleep, but the impact of light and noise pollution is a new finding. Figure 5 (Noise pollution) and Figure 6 (Light pollution) both show concentrated areas of increased noise and light. A University of California, Berkeley study identified that neighborhoods with at least 75% Black residents had median night-time noise levels 4 decibels higher than in neighborhoods without any Black residents. Similarly, research reveals that Black residents were

more likely to live in light polluted areas (Nadybal et al., 2020). Both noise and light pollution have direct effects on the quality of sleep. A recent study noted that adolescents living in light polluted areas sleep on average 11 minutes less than in non-polluted areas (Paksarian et al., 2020). As for noise pollution “There is clear evidence that sleep disturbances are associated with health deterioration, and growing evidence that exposure to noise pollution, around-theclock, negatively affects health” (Halperin, 2014).

Together noise and light pollution significantly impact sleep quality and efficiency as they create environments that make getting sleep and staying asleep difficult.

Source: A Map of America’s Noise Levels.” http://www.popsci.com/map-quietest-places-america

Sleep attitudes influence sleep more than knowledge (Moawad, 2022). Most believe sleep is decided by uncontrollable factors such as genetics, rather than by controllable ones such as behavior. Sleep attitudes were better in those that identified as White and worse in minorities. Minority groups are more likely to believe that poor sleep patterns cannot be changed towards a healthier alternative (Ruggiero et al., 2019). The same study identified a positive correlation between sleep attitudes and sleep quality. Those that believed they could acquire sleep were more likely to, and those that did not, would suffer from poor sleep. This phenomenon is observed across all age groups and is perpetuated through the parent-child relationship. A study observing the parental practices of Head Start parents revealed that 81% of parents believed their child had healthy sleep habits and received sufficient sleep. However, the findings revealed that 50% of the children had poor sleep habits and 33% suffered from insufficient sleep (Bonuck et al., 2016). This discrepancy highlights a misunderstanding about what healthy sleep look likes and over time it could lead to a life-long of poor sleep behaviors. Additionally, as adults “workaholism” or “hustle culture” has encouraged highly productive people to deprioritize sleep. This combination of lack of sleep literacy, and negative attitudes towards sleep worsens a community’s sleep health outcomes.

Across the mentioned factors the most pervasive factor that impacts Black people’s sleep health is racism and discrimination. Housing discrimination has put Black people in adverse sleep environments. Discrimination in the labor forces has been linked to the over assignment of late night and early morning shifts and a lack of access to stable daytime jobs. Attitudes about sleep habits of Black people remain rooted in pseudo-scientific ideologies steeped in racism and left over from slavery. Evidence, however, also links experiences of discrimination and racism with poor sleep, independent of preexisting medical conditions such as depression (Slopen et al., 2016). Another researcher found that discrimination was a unique stressor for Black Americans independent of stress. (Hoggard and Hill, 2018). Additionally, the link between experiencing discrimination and sleep health has been founded across multiple age groups. In 2021 a study found that adolescents encountering daily discrimination experienced changes in sleep, whereas adolescents reporting no discrimination experienced no sleep changes (Xie et al., 2021). While more research is needed to identify the depth of this connection, these findings highlight the overwhelming barriers that exist for Black sleep health.

Across the mentioned factors the most pervasive factor that impacts Black people’s sleep health is racism and discrimination.

Sleep is fundamental to our overall health. Due to a variety of factors, there is a sleep gap between Black and White Americans. To combat the sleep epidemic impacting Black communities, policymakers and community activists should consider:

Increase sleep literacy through national sleep education campaigns that teach the importance and value of sleep health. Sleep scientists such Dr. Aziz Seixas and Dr. Girardin Jean-Louis have found that to improve a person’s sleep, information on better sleep behaviors is one-third of the solution (Perez, 2021). In addition to accurate information there needs to be a persuasive cognitive component that teaches the importance of sleep as well as an emotional component that encourages positive attitudes towards sleep. The best treatment for sleep deprivation is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) that is culturally relevant to Black communities. Developing and disseminating CBT tools widely will increase the sleep literacy of Black communities.

Elevate sleep’s presence in national conversations on Black health. In 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services finally considered improving sleep as a disease prevention goal (Get Enough Sleep | Health.Gov, n.d.). Community activist must continue to push policymakers to prioritize sleep health and advocate for sleep health committees across the public health sector. Incorporating sleep in national public health campaigns and focusing on dispelling long held misinformed beliefs around sleep is necessary to bettering the sleep health of Black Americans.

Explore later start times for public school systems. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that children aged 6–12 years should regularly sleep 9–12 hours and teenagers aged 13–18 years should sleep 8–10 hours (Paruthi et al., 2016). Currently the national average start time for public school systems is 8:00 am. This directly impacts how much sleep K-12 students receive. A loss of 30 minutes to an hour for children and teenagers is more significant to their health than adults as they require more sleep. Research has shown that pushing back start times from 7:30 am to 8:30 am made it easier for students to better the quality and quantity of their sleep (Berry et al., 2021). Due to these findings, California took the steps to mandate a later school start time to improve the sleep quality of adolescents. This mandate will take effect in Fall 2022 and if successful, may compel other states to do the same.

Mandate regulations on shift work and increase the minimum wage. As research shows, shift workers are susceptible to the unconscious or conscious bias of their shift managers. Federal and/or state regulations around shift work should be implemented to control for discrimination. A blind assignment of schedules is recommended to ensure equity in the shift-labor market. Increasing the minimum wage will provide relief to Black workers and provide opportunities to work fewer jobs across the day and night.

Increase access to in-home diagnostic testing for sleep disorders through Medicaid. Sleep disorders such as Obstructive Sleep Apnea are often undiagnosed in Black communities. Having diagnostic materials covered by Medicaid and other healthcare providers could increase the potential for Black people to better understand their sleep health.

CPAR | The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

Currently there are no bills or policies at the federal level that address the sleep health gap. If we seek to improve the health outcomes of Black Americans, a prioritization of sleep in the public health discourse is vital, along with the dissemination of culturally contextual resources and information. Most of the work towards bettering the conditions for Black Americans have been contingent on individual and communal self-advocacy. Supporting Black communities in getting a good night’s rest is vital to bettering the overall health outcomes of Black people. Dismantling the systemic barriers to rest such as economic oppression, environmental racism, and discriminatory policies can be accomplished through collective and legislative actions. The inclusion of sleep health in health equity discussions and addressing the historical realities Black communities face will create more urgency towards action.

Rest is a form of resistance against oppressive power structures and the greatest form of rest is sleep, because sleep is the foundation of good health.

Asif, N., Iqbal, R., & Nazir, C. F. (2017). Human immune system during sleep. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 6(6), 92–96.

Berry, K. M., Erickson, D. J., Berger, A. T., Wahlstrom, K., Iber, C., Full, K. M., Redline, S., & Widome, R. (2021). Association of Delaying School Start Time with Sleep–Wake Behaviors Among Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(5), 831–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.04.030

Bonuck, K. A., Schwartz, B., & Schechter, C. (2016). Sleep health literacy in head start families and staff: Exploratory study of knowledge, motivation, and competencies to promote healthy sleep. Sleep Health, 2(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.12.002

Cartwright, S. (1851). Africans in America/Part 4/”Diseases and Peculiarities”. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h3106t.html

Calhoun, D. A., & Harding, S. M. (2010). Sleep and hypertension. Chest, 138(2), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-2954

CDC - Data and Statistics—Sleep and Sleep Disorders. (2021, September 13). https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

Cedernaes, J., Schönke, M., Westholm, J. O., Mi, J., Chibalin, A., Voisin, S., Osler, M., Vogel, H., Hörnaeus, K., Dickson, S. L., Lind, S. B., Bergquist, J., Schiöth, H. B., Zierath, J. R., & Benedict, C. (2018). Acute sleep loss results in tissue-specific alterations in genome-wide DNA methylation state and metabolic fuel utilization in humans. Science Advances, 4(8), eaar8590. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar8590

Christensen, P., Sarmiento-Barbieri, I., & Timmins, C. (2022). Housing Discrimination and the Toxics Exposure Gap in the United States: Evidence from the Rental Market. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00992

Daghlas, I., Dashti, H. S., Lane, J., Aragam, K. G., Rutter, M. K., Saxena, R., & Vetter, C. (2019). Sleep Duration and Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 74(10), 1304–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.022

Douglass, Frederick, and William Lloyd Garrison. Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1849.

Dudley, K. A., & Patel, S. R. (2016). Disparities and Genetic Risk Factors in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep Medicine, 18, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.015

Frey, W. H. (2019, August 29). Six maps that reveal America’s expanding racial diversity. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-racial-diversity-in-six-maps/

Get Enough Sleep—MyHealthfinder | health.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/healthy-living/mental-health-and-relationships/get-enough-sleep

Halperin, D. (2014). Environmental noise and sleep disturbances: A threat to health? Sleep Science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 7(4), 209–212. PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slsci.2014.11.003

Heart Disease and African Americans—The Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Retrieved July 26, 2022, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=19

Hoggard, L. S., & Hill, L. K. (2018). Examining How Racial Discrimination Impacts Sleep Quality in African Americans: Is Perseveration the Answer? Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 16(5), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2016.1228648

Jefferson, T. (1853). Notes on the state of Virginia. Richmond, Va., J. W. Randolph. http://archive.org/details/notesonstateofvi01jeff

Johnson, D. A., Lewis, T. T., Guo, N., Jackson, C. L., Sims, M., Wilson, J. G., Diez Roux, A. V., Williams, D. R., & Redline, S. (2021). Associations between everyday discrimination and sleep quality and duration among African Americans over time in the Jackson Heart Study. Sleep, 44(12), zsab162. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab162

Leary, J. D. (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Milwaukie, Oregon: Uptone Press, [2005] ©2005. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910095931802121

Lucassen, E. A., Rother, K. I., & Cizza, G. (2012). Interacting epidemics? Sleep curtailment, insulin resistance, and obesity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1264(1), 110–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06655.x

CPAR | The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S134864

Merling, L. (2016, September 22). Black Women Are the Only Group More Likely to Work Multiple Jobs Now than a Decade Ago. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/black-women-are-the-only-group-more-likely-to-work-multiple-jobs-now-than-a-decade-ago/

Miller, A. L., Lumeng, J. C., & LeBourgeois, M. K. (2015). Sleep patterns and obesity in childhood. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 22(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000125

Moawad, H. (n.d.). Sleep Attitudes Influence Sleep More than Knowledge. Psychiatric Times. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/sleep-attitudes-influence-sleep-more-than-knowledge

Nadybal, S. M., Collins, T. W., & Grineski, S. E. (2020). Light pollution inequities in the continental United States: A distributive environmental justice analysis. Environmental Research, 189, 109959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109959

Nunez, K. (2020, July 20). Why Do We Sleep? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/why-do-we-sleep

Paksarian, D., Rudolph, K. E., Stapp, E. K., Dunster, G. P., He, J., Mennitt, D., Hattar, S., Casey, J. A., James, P., & Merikangas, K. R. (2020). Association of Outdoor Artificial Light at Night With Mental Disorders and Sleep Patterns Among US Adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(12), 1266–1275. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1935

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L. J., D’Ambrosio, C., Hall, W. A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R. M., Malow, B. A., Maski, K., Nichols, C., Quan, S. F., Rosen, C. L., Troester, M. M., & Wise, M. S. (2016). Recommended Amount of Sleep for Pediatric Populations: A Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785–786. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866

Perez, R. (n.d.). Poor sleep takes a heavy toll on communities of color. Can scientists help? Science.Org. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.science.org/content/article/poor-sleep-takes-heavy-toll-communities-color-can-scientists-help

PRB. (n.d.). A Demographic Profile of U.S. Workers Around the Clock. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/resources/a-demographic-profile-of-u-s-workers-around-the-clock/ Pultarova, Tereza published, T. P. (2017, May 24). Trouble Sleeping? Air Pollution Could Be the Culprit. Livescience.Com. https://www.livescience.com/59253-air-pollution-linked-to-worse-sleep.html

Ruggiero, A. R., Peach, H. D., & Gaultney, J. F. (2019). Association of sleep attitudes with sleep hygiene, duration, and quality: A survey exploration of the moderating effect of age, gender, race, and perceived socioeconomic status. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 7(1), 19–44. PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2019.1567343

Schmidt, M. H., Swang, T. W., Hamilton, I. M., & Best, J. A. (2017). State-dependent metabolic partitioning and energy conservation: A theoretical framework for understanding the function of sleep. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0185746. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185746

Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2019, October 16). It’s About Time: How Work Schedule Instability Matters for Workers, Families, and Racial Inequality. The Shift Project. https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/its-about-time-how-work-schedule-instability-matters-for-workers-families-and-racial-inequality/

Singh S, A., Dhanasekaran, D., Ganamurali, N., L, P., & Sabarathinam, S. (2021). Junk food-induced obesity- a growing threat to youngsters during the pandemic. Obesity Medicine, 26, 100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obmed.2021.100364

Slopen, N., Lewis, T. T., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Discrimination and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 18, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.012

Stroke and African Americans—The Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Retrieved May 30, 2022, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=28

Table 7. Workers by shift usually worked and selected characteristics, averages for the period 2017-2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex2.t07.htm#cps_jf_table7.f.1

U.S. poverty rate, by ethnicity 2020. (n.d.). Statista. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/200476/us-poverty-rate-by-ethnic-group/

Vallat, R., Shah, V. D., Redline, S., Attia, P., & Walker, M. P. (2020). Broken sleep predicts hardened blood vessels. PLOS Biology, 18(6), e3000726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000726

CPAR | The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes

Van Cauter, E., Punjabi, N., & Reutrakul, S. (n.d.). Diabetes in America, 3rd Edition | NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved May 23, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/diabetes-in-america-3rd-edition

Xie, M., Yip, T., Cham, H., & El-Sheikh, M. (2021). The Impact of Daily Discrimination on Sleep/Wake Problem Trajectories Among Diverse Adolescents. Child Development, 92(5), e1061–e1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13605

Zizi, F., Pandey, A., Murrray-Bachmann, R., Vincent, M., McFarlane, S., Ogedegbe, G., & Jean-Louis, G. (2012). Race/Ethnicity, Sleep Duration, and Diabetes Mellitus: Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. The American Journal of Medicine, 125(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.020

CPAR | The Power of Rest: Examining the Racial Disparities of Sleep and its Connections to Black Health Outcomes