29 minute read

Unlocking the value of MMC for Irish construction

In 2016, Mark Farmer, CEO of UK-based specialist construction consultancy Cast, authored the Farmer Review, an influential independent government review of the UK’s construction labour model, which he entitled ‘Modernise or Die’. In 2019, he was appointed the UK government’s Champion for Modern Methods of Construction in Housebuilding.

Farmer is an internationally-respected commentator on construction technology and how MMC, in particular, can significantly improve productivity and reduce carbon emissions. He has also been a regular contributor to the MMC dialogue in Ireland over the past few years.

Advertisement

Modernise Or Die

In his 2016 review of the UK construction industry, Farmer set out what he saw as the obvious steps that the industry needed to take if it was to remain fit for purpose. It was clear to him that one of the biggest threats to the sector was workforce size and demographics. An ageing and much- depleted workforce has since been further impacted by the knock-on impacts of Brexit and Covid-19.

In 2016, Farmer saw a huge productivity challenge coming, and he said that the sector needed to look at alternatives to traditional methods of construction to be able to deliver and achieve levels of efficiency not previously considered possible.

Today, Mark Farmer says that progress has been made, but it has been slow.

“Many things have changed in the UK construction sector since 2016, and they continue to change. But the transition from less efficient traditional construction methods has been a slow journey, which I had anticipated would be the case. It was a huge ask to expect the construction industry to change from its established and embedded building practices, but it became clear in time to the sector that it needed to move to more modern ways of building if it was to be productive and sustainable.

The report received a positive reaction from the UK government and the construction sector.

“Some of my recommendations related to policies and initiatives the government could introduce as a policy maker and as a client of the industry to drive positive change.

“Homebuilding is one area that has benefitted from government programmes. In terms of the actions that have been taken, various initiatives and programmes are now in train, including the UK Affordable Homes Programme 2021-2026, which is linked to the need to use MMC as part of new home building delivery.

“This has been a stimulating activity in the market and has been a catalyst in getting the sector to move to more innovative construction techniques, MMC usage and digital technology,” he adds. “I think what’s really interesting is that the initial period of government-led interventions to try and push the industry to a different place has moved to a new phase where the industry is increasingly recognising the need to be proactive in that transition.

“Irrespective of the government prodding it towards a different place, we now have contractors, house builders and trade subcontractors in the UK addressing the big challenges, particularly around its workforce.”

COVID-19 IMPACTS

The Covid-19 pandemic has also had a significant impact on that journey and was quite a big interruption. Farmer comments that the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in contractors pivoting to more lean practices and rolling out digital construction technologies. Previously bustling sites with trades and construction workers trying to work around each other were replaced with socially-distanced task-at-hand focused operations. Greater efficiency was one of the early gains from the pivot in response to the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“In the UK, as in Ireland, we restarted construction quickly with social distancing rules and a new standard operating procedure, and productivity improved.

“Site productivity improved because work was carried out in a more structured, orderly and efficient way. Workers were not crawling all over each other to get in to complete their individual tasks. Better planning and lean became part of the process.

“Unfortunately, post-lockdown, we seem to be back to square one. Evidence suggests that our productivity has tailed off dramatically from where we were preCovid. It’s difficult to work out why this is the case. But anecdotal evidence suggests that construction has a bigger productivity issue now. We need to look at this to regain momentum, otherwise, the efficiencies temporarily gained during the pandemic will become wasted opportunities.”

Irish Construction Sector

Irish construction has also been going through a metamorphosis in recent years, with the Construction Sector Group’s Innovation and Digital Adoption SubGroup bringing together stakeholders from private and public sectors to transform Ireland’s construction sector into a modern, efficient and sustainable industry.

Mark Farmer has been a regular visitor to Ireland since the publication of his UK review and is very much aware of how the sector is tackling the challenge.

Most recently, in February, he attended a forum of industry stakeholders where he had the opportunity to speak with Enterprise Minister Simon Coveney.

“I have been collaborating with the Irish construction sector for the past five or so years and have spoken at a number of conferences, and I value the links I have made.

“Recently, I was at a stakeholder event in Trinity College that looked at how the Housing for All plan can be mobilised through a different approach to housing delivery. I had the pleasure of meeting Minster Coveney, and we discussed the importance of reforming and modernising home-building delivery in the face of the challenges that Ireland is facing. The challenges are very similar to those being faced by the UK sector in relation to workforce productivity, efficiency and quality issues, and, of course, reducing carbon.

Farmer notes that the Irish government has been very proactive by consulting with the sector on what needs to happen and setting out long terms plans such as Project Ireland 2040 and Housing for All. It has also been supportive in incentivising the sector to modernise.

“The Irish government has changed policies and incentivised change by providing resources such as funding and land. But the industry as a whole must want to change, and this also means changing culture.

“From what I have seen, many developers and contractors are making decisions for their own businesses’ health to pivot towards more modern, innovative construction techniques. But they also need to bring their subcontractors along with them and recognise that if they are using MMC, offsite factories require upfront funding and pipeline surety in order to be viable.

“Government programmes such as Project Ireland 2040 and Housing for All show the Irish government’s determination to drive change, and the industry is also starting to make progress in working through the challenges.”

Mmc In A Traditional Building Market

Mark Farmer is passionate about the benefits that can be gained from developing an indigenous off-site manufacturing industry but adds that it is essential that contractors and developers understand

Discover Easy Comfort with Pipelife Eco

that manufacturing facilities require a lot of up-front investment and pipeline security to survive and mature.

“MMC is a basic manufacturing model with the fixed costs of a factory, plant and machinery as well as full-time labour. It requires a lot of investment before anything makes it onto the production line.

“This does not sit well with an industry that’s used to a cyclical boom and bust profile of demand and the indeterminate nature of the planning system,” he adds. “Committing resources and investment to assets without necessarily knowing that you have continuity of demand is counter-intuitive.

“To survive and thrive, MMC requires a different business model to traditional construction. Investment has to be linked to diversified end demand. Setting up a factory on a speculative basis and hoping someone will consistently buy your product at a constant rate is an extremely high-risk strategy. Over the past few years, there have been failures in the UK, where people set up factories and haven’t linked investment to surety of demand, and, as a result, they have failed.

He continues. “Many offsite firms are still in start-up mode. It can take years to become a mature business. So, deep pockets are required. There are players in the UK who have made significant investments of tens of millions of pounds and have still not reached profit-making maturity.”

He says that the business model has to be linked to client investment with sufficient continuous demand to de-risk the investment.

“It should also be noted that creating a mega-factory with centralised production isn’t always necessary. Small is agile and carries less risk.”

Mmc Business Operational Models

Mark Farmer says that vertically integrated delivery is the most insulated business model for an MMC manufacturer. “A developer with land and planning permission has the building and selling/renting element of their business in-house.

“The next stage of taking more control of the business is moving from building to manufacturing the product, creating an end-to-end process. When the developer or builder decides to manufacture their buildings, they are effectively taking a vertically integrated approach, whereby they can also control the quality of production, reduce embodied and operational carbon and align what is required to the end customer.”

He continues, “A manufacturer who sells their product to a third-party house builder, developer or housing association bears the risk of being a commoditised transaction and may not know where the next job is coming from or at what price. Survival and maturing as a business is about resiliency.

“If a manufacturing business is not part of a vertically integrated chain, they are by necessity marketing and selling their product externally. The best strategy in this scenario is to have a diverse client base with as many clients as possible, preferably with some being counter-cyclical.

“Some manufacturers work across different sectors, such as housing, education, health, etc. This is particularly popular with modular manufacturers whose product is adaptable if economies of scale can be reached. This can be a very resilient business if a good client base is in place.”

He adds that manufacturers can often also provide a rental offer, which ensures there is cash generation in the business. “This has been working particularly well in the UK in the education and health sectors, where rented units garner a monthly income for manufacturers.

“The vertically integrated model, in my experience, tends to be the most resilient, and most successful businesses to date tend to be SMEs, not mega-factories. Larger plants are cash hungry and must produce thousands of units to survive. There is a role for this centrally-industrialised model in the housebuilding market, but we are not yet at that level of acceptance and maturity, so we need alternative pathways as well.”

Hybrid Operation Models

Whatever form of MMC is incorporated into a project, there will always be a need for some level of traditional building activity on site, particularly where panels, pods and component sub-assemblies are being brought to site.

Mark Farmer explains, “MMC is nuanced in that there is a hybrid element to it where factory production and traditional building are combined. Panels, pods, and component subassemblies are delivered to site, construction workers prepare the site, install them and build traditionally around them. There will always be some level of modern and traditional crossover.”

Farmer sees a gradual move towards what he calls “pre-manufactured value (PMV). This is the financial proportion of a construction project’s gross construction cost derived through pre-manufacturing.

His consultancy, Cast, has pioneered the use of PMV as a key industry metric for measuring progress towards modernisation. The use of a PMV proxy measure enables construction project teams to adapt designs, supply chain, logistics and site-based construction and assembly choices to deliver improvements against the following criteria:

• Predictability of outcome

• Productivity improvement and waste reduction

• Quality & performance

• On-site delivery speed and site overheads

• Transactional costs

• Community disruption

• Site health and safety risk. He comments that PMV is a strong proxy for multiple industry performance measures, and its use in early target setting and gauging projects is a vital element of driving behavioural change, albeit it should be used alongside more qualitative measures for the best effect.

Understand Mmc Investment

Expanding on the establishment of a sustainable MMC sector, Mark Farmer says that clients need to understand that, unlike traditional construction methods, manufacturing plants have upfront costs and need pipeline security to invest in production.

“There are a lot of challenges entering the construction market with a different approach to how you physically design and build your product. The construction industry is notoriously traditional, and anyone doing anything different is up against it.

“Manufacturing models need upfront investment. They need equity or access to funding, which is not always easy, particularly for an SME.

“It is critically important to think about the execution and delivery model. The significant bit in all of this is that you can have a good plan on paper, but I’ve seen many businesses fail because they have a poorly-executed business plan in practice. Either the business model linked to demand has been wrong, or the physical product hasn’t been good enough.

“Then, you have to combine manufacturing technologies and plant and equipment with people. To this end, we have a whole new part of our industry that has not existed up to now. We have had trades – bricklayers, carpenters, electricians, plumbers, and the like. However, apprenticeship models for hybrid trade/manufacturing skills and for outright manufacturing technicians or construction and assembly technicians is a new idea, and governments have a role to play in supporting the creation of these new apprenticeship streams. These apprenticeships then need to give people real qualifications recognised industry-wide so that they can move jobs.

“The employment model for manufacturing is also different to traditional construction. Traditional construction is very much self-employment-led. It’s all about casual labour. To run a factory, you need to have permanently employed staff that are properly trained and have good working conditions. To attract the right people, you must create a better working environment and offer better packages and security.

“Anyone starting out in an MMC business has to think about their workforce. Where are you going to get it from? How are you going to train it? How are you going to keep it? How are you going to attract others to come to your business? And, ultimately, how will you physically manufacture products in a way that is to a quality level that the clients want?

“It’s all common sense, but you’d be surprised how many people don’t think through some of those common steps, those basic steps to running a business. But there are examples of people who have cracked and continue to crack the MMC nut. So it’s not impossible.”

Next Steps

So back to the challenge at hand as Mark Farmer sees it for the construction industry to modernise or die.

“I have travelled a lot over the past few years and observed the appetite for change in construction industries across the world. I have been working with various parties in Ireland and am aware of all the plans and initiatives in place to change how things are done.

“Forward-looking construction sectors are looking to evolve. Ireland has been very innovative in its approach to addressing the challenge, changing house-building and other construction models and developing more integrated supply chain arrangements. Combine this with the government’s interest and desire to change how things are built, particularly in relation to Housing for All, and I think there is a real willingness to do things differently.

“It doesn’t mean the challenges will disappear because they won’t, or that the government can’t do more because it can. But no one wants to repeat the mistakes of the past. Ireland has gone through a lot of boom and bust cycles over the years. The Celtic Tiger experience damaged the property and construction sector, and there has been a real appetite to repair the industry long-term so it can provide proper sustainable, high-quality jobs for people, better wages, better productivity and ultimately cheaper but high-quality buildings. This will benefit everyone economically, and I sense that Ireland is an exciting hotbed of thinking on the subject at this time,” Mark Farmer concludes.

Respond’s recently-appointed Director of Investment and Development, Parag Joglekar, oversees over €1.5bn in housing under construction. Having been with the AHB for over 20 years, he is well acquainted with the complexities of delivering social housing at scale.

Established in 1982, the approved housing body (AHB) Respond has built more than 7,000 units nationwide over the years, providing homes for families and individuals who need them. The organisation also provides community services, such as learning and school-age care, day care for older people, family support, refugee resettlement and family homeless services.

Over the past five years, Respond has commenced 3,347 homes with a value of just over €1.03bn. It currently has 1,433 new homes under construction, with construction schemes ranging in value from €15m to €65m and total programme value in excess of €1.5bn.

As a direct response to Housing for All, the Respond board, in a mid-term review of its strategic plan, set out an increased delivery target. This included aiming to deliver up to 1,000 social homes and 250 cost-rental homes annually from the end of 2024.

Respond’s recently appointed Director of Investment and Development, Parag Joglekar, joined the AHB in 2001. He is a registered architect in Ireland and the UK. He has over 25 years of experience in urban design, private and public housing, regeneration, commercial projects and risk and asset management, in addition to managing design and construction contracts across Ireland, the UK and India.

Joglekar leads Respond’s multidisciplinary development team of 20 construction professionals, responsible for its social and cost rental homes building programme.

He explains that Respond’s core goal is to create a positive future for people by alleviating poverty and creating vibrant, socially integrated communities.

“We achieve this by providing access to education, childcare, community development programmes, family support, early learning and school-age care, day care for older people, family homeless services and refugee resettlement,” Parag Joglekar comments. “When people receive the keys to their new home from Respond, this marks the start of a life-long relationship that they will have with us. Each of our developments is assigned a tenant relations officer who works with tenants so they become part of a community. The Respond housing team oversees asset management services, addressing maintenance and other related issues.”

Joglekar notes that being a large social housing provider allows the Respond team to get involved in some really innovative work.

“We are, for instance, partnering with the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI) to deliver what we believe is a first – a Brain Health Village. This is a pilot project from which we hope to use the learnings for all our tenants.”

Housing For All

Parag Joglekar believes that the biggest opportunity to come out of Housing for All for AHBs is the provision of multi-annual funding with a substantial government investment of €4bn per year until 2030.

“Providing everyone is operating in a stable economic environment, such an investment by the State has the potential to address the core objective of Housing for All.

“As a result of Housing for All, we have an opportunity for innovation and greater collaboration between the private, voluntary and public sectors to deliver real change through planning and procurement reform, addressing the need for multiple models for housing demand-access-affordability, investment in communities, social inclusion, climate agenda, social and physical infrastructure.

“As an AHB, Respond has a central role to play to support the delivery of the Housing for All plan, including the development of cost rental homes.”

Joglekar acknowledges that Housing for All also presents several challenges for AHBs.

“Aside from the essential aspect of financing, the delivery of Housing for All will depend on the commitment and collaboration of its key stakeholders,” he comments. “The ambition of Housing for All means it will require continuous monitoring of its targets. As with any plan, flexibility is important to facilitate agility and adaptability in an ever-changing economic context. This must be supported through legislative and financial interventions, as and when required.”

He continues, “It will be critical to balance the various facets of planning measures, development viability and facilitating physical infrastructure. This is the biggest challenge in the midst of high inflation and the overall context we are operating within.”

He believes that aligning objectives between the National Development Plan (NDP) and National Planning Framework (NPF) will also be critical, as the focus should not be on housing delivery and targets alone.

“In Respond, we firmly believe that the success and sustainability of any development depend on access to key social and physical infrastructure and, in particular, transport, utilities, schools, hospitals and local economic and commercial zones, which in turn contribute to the sustainability and climate agenda.”

Delivery Models

Parag Joglekar recognises that the private sector, developers and builders have a central role to play in helping deliver various social housing.

Respond’s housing investment programme includes various models for the delivery of social and cost-rental housing. One of these strands is engagement with the private sector to deliver homes.

“We partner with the Irish Home Builders Association (IHBA), Construction Industry Federation (CIF) and other stakeholders, which accounts for just over 80% of our delivery programme,” he explains. “The majority of our delivery is new construction where Respond acquires the site and facilitates financing of construction stage payments in accordance with specified deliverables. This forward funding model has unlocked sites to deliver new housing, which otherwise would have been unviable because of financing costs. Developers and builders submit proposals for new housing schemes in response to our Request for Tenders. This tender process is advertised through the eTenders portal. Following the assessment of proposals, including support from the relevant local authority in terms of housing need and demand, tenders are put forward for review and approval by the Respond executive, development board subcommittee and finally, our board.

“Once Heads of Terms are issued, we commence contract and funding stages with a view to begin construction and deliver schemes based on agreed programmes.

“In addition to our own technical team, we engage the services of external registered architects, planners, chartered quantity surveyors for cost validation, chartered fire engineers and building surveyors and any other specialist consultants through various project stages.”

Funding Models

Joglekar says that the Capital Advance Leasing Facility (CALF) continues to be the primary source of facilitating the delivery of social housing, with the remainder of funding, in the case of Respond, coming from the Housing Finance Agency plc (HFA).

“Respond recognises the vital role that the HFA plays in facilitating the delivery of new housing for local authorities and AHBs through its lending. CALF is currently undergoing refinements to facilitate some of the current risks and challenges in the market pertaining to viability, such as inflation and interest rate increases.

“96% of Respond’s development pipeline is funded through CALF and 2% through Cost Rental Equity Loans (CRELs), with the remainder funding coming from the HFA.

“This is debt finance over periods ranging from 20 to 30 years. Only 2% of our development pipeline is funded through a grant under the Capital Assistance Scheme (CAS), which facilitates housing for specific tenures such as older persons, persons with disabilities, homelessness, etc.”

Land Availability

Joglekar notes that providing access to public land is a key aim of Housing for All, but it also needs to be serviced land.

“While it aims to make public land available for building new homes, there are measures set out for zoning of serviced land that allow housing demand and need in the local area to be met. Respond is currently involved in developing projects on land made available through local authorities and the Housing Agency.

“Access to land has either been through local authority Expressions of Interest (EOI) or existing sites in land aggregation schemes where Respond was previously involved.

“Across these sites/land parcels, Respond is working with relevant local authorities to secure planning grants either through a standard planning permission or through a Part VIII planning process.

“Upon securing of planning permission, Respond undertakes further detailed design development, tenders schemes under public works contracts and progresses delivery by securing funding through CALF-PAA, CREL and HFA funding or grant under CAS funding.”

Private Sector Collaboration

In addition to the current 1,433 homes on various sites, Respond is hoping to commence a number of new schemes throughout 2023 and 2024. Its development team is working to initiate the construction of an additional 1,350 homes with planning in its existing development pipeline.

Housing for All has increased engagement between Respond, developers and builders.

“Respond’s engagement with the private sector – developers/builders and main contractors has increased significantly since the launch of Housing for All,” Joglekar notes. “Our development team is involved in many projects in urban and non-urban areas with developers and builders of varying size and capacity. The projects can range from complex schemes involving varied housing

Respond’s Redforge Road Housing scheme in Cork.

typologies and tenures to straightforward housing schemes on greenfield or brownfield sites and/or regeneration areas. Respond has also been involved in repurposing existing buildings into new homes.

“We are working on viability assessments on several new schemes nationwide that can potentially deliver social and cost rental homes. All of this work is through the support of local authorities, the Department of Housing, the Housing Agency, HFA, IHBA, CIF and other stakeholders.

“As Respond works to add to the national housing stock, our focus remains on new construction to deliver cost rental and social housing.”

Changing Technologies

Over the past few years, Parag Joglekar says that he has noted an increased awareness and desire by various stakeholders to engage in modern methods of construction (MMC).

“This has been most notable in urban areas across larger sites involving apartments and, in some instances, standard houses,” he comments. “We have seen early engagement, from planning stage, between developer, design teams and main contractors, as well as specialist subcontractors. This engagement or collaboration focuses on the speed of delivery of new homes, quality control, health and safety and environmental performance.

“Some of the schemes developed for Respond have included the use of prefabricated wall panels, balcony systems for apartments and bathroom pods,” he adds. ”Some traditional housing units we have developed have also been manufactured offsite utilising timber frame. We are currently working on a large apartment scheme where composite architectural wall panels are being used. These wall panels are being designed and manufactured in a coordinated approach using BIM. This requires collaboration between our design team, the main contractor and specialist subcontractors. “In addition, the scheme incorporates bathroom pods, currently in production.”

Joglekar believes that while MMC has many benefits, several challenges exist, including perceptions of build types, the need for scale/volume, understanding the maintenance of such buildings and contribution to placemaking.

“Procurement methodologies also need to be further refined to allow the adoption of MMC from an early design stage. An appropriate procurement methodology and securing relevant warranties must be facilitators and not hinder adoption of new construction technologies.”

Sustainability

Finally, much has changed in the social housing sustainability space in more recent times. “The Respond development team have a heightened awareness of reducing carbon emissions throughout a building’s life cycle from the initial design to the refurbishment or eventual disposal of a building,” Parag Joglekar explains. “On all of our projects, we now work with designers, contractors and other stakeholders to assess the carbon footprint of our buildings. This is then used to plan an effective reduction strategy through all stages of the building life cycle.”

The sustainability assessments are carried out across the following categories:

• Product stage,

• Construction stage

• Use stage (includes maintenance, repair, refurbishment and replacement),

• End of life stage, and

• Beyond building life cycle (Promoting circular economy).

“As an organisation operating for over 40 years, a significant proportion of Respond’s stock is over 25 years old. It is essential that we maintain and improve these homes so that our tenants can continue to enjoy them.

“Energy efficiency and providing warm and affordable homes continues to be a priority for Respond. In 2022, we invested another €1.5m in our energy retrofit programme, utilising matching funding from the Sustainable Energy Authority Ireland (SEAI), raising the overall investment in the year to over €3m. Our total energy retrofit investment over the past 10 years is in excess of €34m. Improvements in our retrofit programmes included renewable heating, windows, doors and insulation upgrades,” he concludes.

Woodside, Enniskerry Road, Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown.

Recent Respond Projects

First purpose-built cost-rental homes

– Woodside, Enniskerry Road, Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown

Respond delivered the first purposebuilt cost-rental homes in Ireland as part of a mixed tenure development on Enniskerry Road in Dún LaoghaireRathdown.

This project resulted from an innovative collaboration between Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, the Housing Agency, the Housing Finance Agency, the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, Respond and Tuath Housing Association. Respond was the main employer of the scheme, and it worked with the stakeholder partners to deliver 155 social and affordable homes and is now managing the homes for tenants, together with Tuath.

The scheme won awards at the National Property Awards 2022 and the Chartered Institute of Housing Working in Partnership Awards 2022.

St Doolagh’s

Sustainable social housing

– St Doolagh’s Oaks, Malahide Road, Dublin

The St Doolagh’s Oaks housing scheme comprises 29 homes in a mix of one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments. The scheme is located close to retail and public facilities, including schools, health services and sports venues. All 59 units have air-to-water heating systems installed along with photovoltaic (PV) panels on the roof, green roof structures and heat recovery heating.

This development is an exemplar scheme showing that sustainability does not have to be beyond the realm of social housing.

Construction Sales

Carlow, Dublin, Kildare, Kilkenny, Laois, Louth, Meath, Monaghan, Offaly, Tipperary, Waterford, Westmeath, Wexford, Wicklow

Shane Leavy 087 091 7184 shane leavy@liffeyd com

Construction Sales Cavan, Clare, Cork, Donegal, Galway, Kerry, Leitrim, Limerick, Longford, Mayo, Roscommon, Sligo

Paul Burke 087 640 0811 paul burke@liffeyd com

Mass timber is a category of engineered wood products typically comprising large, solid wood panels, columns or beams, often manufactured off-site for load-bearing wall, floor, and roof construction. Mass timber includes cross-laminated timber (CLT), naillaminated timber (NLT), dowel-laminated timber (DLT) and glue-laminated timber (glulam or GLT).

Developed in the 1990s, CLT is a popular mass timber material for residential and commercial structures across much of mainland Europe and North America. It comprises several layers of structural grade timber arranged crosswise and glued together.

CLT is a CO2 reservoir and, therefore, a zero-carbon alternative to concrete to form the walls, roofs, floors and ceilings of a building. It is particularly well-suited to multi-storey taller wood construction and can include pre-insulated wall and roof sections.

In Ireland, under current regulations, timber or, more specifically, timber frame and CLT is only used to construct buildings of up to 10 metres in height or three storeys. While planning applications have been made to use CLT for buildings above 10 metres, it has only featured as an elemental part of non-complex buildings or single-storey extensions.

Irish Green Building Council

The Irish Green Building Council (IGBC) construction sector decarbonisation roadmap Building a Zero Carbon Ireland: A Roadmap to decarbonise Ireland’s Built Environment across its Whole Life Cycle calls for greater use of bio-based materials, such as timber, to reduce the embodied carbon emissions of the built environment. More specifically, the roadmap includes a number of recommendations on mass timber and CLT.

These include:

- Reviewing Technical Guidance Document (TGD) Part B (Fire Safety) to reflect international research and developments in mass timber construction and best practice, and:

- Providing financial incentives or directly funding research and production facilities for biobased construction materials (eg, CLT, sheep’s wool, hemp, mycelium, and straw) such as through an accelerator scheme. A review of TGD Part B of the building regulations was due to complete its public consultation stage at the end of April 2023.

In parallel, much out of the necessity to address the shortfall in housing output as well as meeting commitments as set out in the government’s Climate Action Plan 2023, namely, reduce carbon emissions by 51% by 2030, a number of government ministers and senior civil servants are now considering various additional solutions to meet housing targets and carbon emission reduction goals.

Barriers To Progress

CLT is one of the solutions currently under review. However, a couple of substantial stumbling blocks need to be addressed if the full potential of CLT is to be realised.

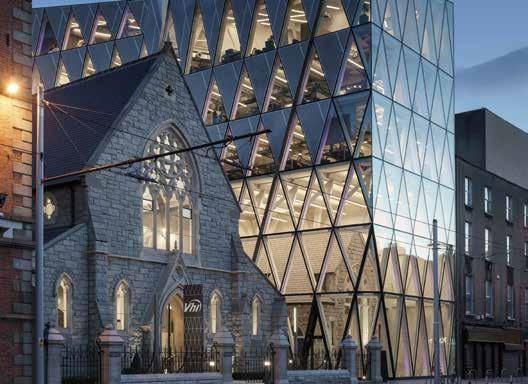

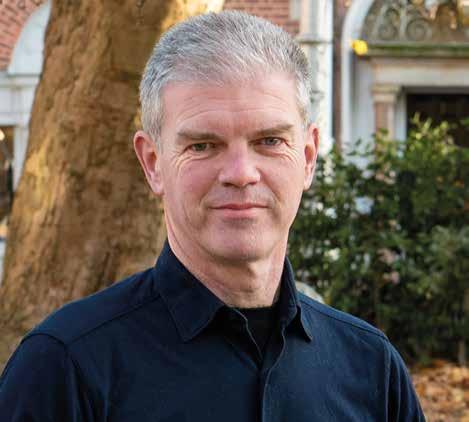

John Casey, founder and Managing Director of CORA Consulting Engineers, has a long record of working with timber, steel and concrete as structural elements in buildings. Two of his firm’s most notable projects are the VHI building exoskeleton frame on Abbey Street in Dublin, and the 6,500-sq-foot Barretstown Gang Camp glulam pavilion with dining hall, kitchens, office space and rest-rooms in Co Kildare.

Casey is a member of the IGBC Mass Timber Construction Committee and has been part of recent discussions with various government departments on the impediments to its use in the construction of more complex buildings.

Casey believes that if the way was cleared for CLT to become a mainstream building material in Ireland as it is in Europe, it would have an immediate impact on increasing housing output, particularly apartment construction. It would also dramatically reduce the embodied carbon of our new building stock.

“CLT is a commonly accepted building material in many countries across Europe where it is used to construct buildings of up to and over 10 storeys in height,” John Casey explains.

“In Ireland, off-site construction techniques, such as precast concrete manufacturing, have producers at maximum output at this time. We understand that precast concrete products cannot be supplied quickly enough to meet the needs of the industry. The timber in CLT has sequestered carbon dioxide as it grew, and this is locked into the timber while used as CLT. From examples of buildings both in Europe and North America, it has proven structural alternative to concrete, but Irish regulators have been slow to warm to it.”

Agr Ment Certification

In recent discussions with government departments, the issue of requiring an Agrément certificate for CLT has been raised as a stipulation for its use. John Casey does not agree that an Agrément certificate is necessary. He believes that the material just needs to be CE marked.

“CE marking indicates that a product has been assessed in accordance with a European technical assessment, which enables a declaration of performance to be drawn up and the CE mark affixed by the manufacturer. It is required for products manufactured in Europe and other parts of the world that are then marketed in the EU.”

Agrément certification is designed specifically for new building materials, products and processes in Ireland that do not yet have a long history of use and for which published national standards do not yet exist. NSAI Agrément assesses, specifies testing, and, where appropriate, issues Agrément certificates for such products.

“CLT has been in use since the early 1990s,” Casey explains. There are 71 largescale CLT manufacturing facilities operating across Europe, requiring investments of up to €50m to build. It is an established building system for all types of buildings, including taller buildings in many EU countries.

“Despite this, civil servants and fire officers involved in construction regulation in Ireland refer to CLT as an innovative product. To get Agrément certification, a CLT manufacturer would have to submit their product to the NSAI for Agrément assessment, which could take up to a year or more with a significant costs attached. But, then, at the end of this process, if successful, the certificate will permit access to the Irish market, where building regulations don’t allow timber buildings over 10 metres.

“This process would have to be undertaken separately by each manufacturer. So, no manufacturer will spend money on the assessment because even if they get an Agrément certificate, they will only have access to a market where their product can be used up to three stories.”

“There are a number of Irish companies supplying mass timber products, including CLT, which is imported, but not at a scale that would be required to deliver large-scale housing.

“It should be noted that a number of the international developers operating in Ireland are experienced in building with CLT in other parts of Europe and North America and would have a ready supply chain to deliver the product. It should also be noted that there is a ready supply of raw material if a manufacturing plant were ever to be constructed, as the timber grown in Ireland is ideal for the production of CLT.

Mass Timber And Timber Frame

He continues, “Timber frame construction has been a mainstay of Irish construction for many years. Irish Standard IS EN 440 covers the design, manufacture, supply and installation and certification of timber frame buildings. It can comprise many parts, including insulation, membranes, etc. These are put together in a factory and brought to site on the back of a truck, then put together, and the entire assembly is certified.

“Mass timber is a simpler product. It is a direct zero-carbon replacement for traditional concrete, blockwork and precast concrete. You replace the concrete elements with mass timber. All other elements, such as insulation, membranes, brick, etc, are separate and are incorporated afterwards.”

Technical Guidance Document B

TGD B has been under review for revision for the past two years, and a public consultation process concludes at the end of April.

“The revised draft for TGD B hasn’t changed very much in terms of mass timber,” John Casey explains. “One of the proposed clauses advises that no combustible material shall be used in compartment floors above 11 metres in height, previously 10 metres. That means that any building above three storeys still can’t use timber or other mass timber elements.

“But other clauses in the fire regulations allow a ‘prescriptive approach’ to be taken. This means that if a fire consultant could demonstrate how the building would behave in a fire and demonstrate that it would pass all the necessary criteria, it would be acceptable for a fire officer to grant a fire certificate for the proposed building. But, to date, no fire officer has granted a fire certificate to any timber building above 10 metres because they are holding fast on the height clause.

“Anyone who submits a fire certificate application for a mass timber building in Ireland is going to struggle to receive a grant because there is little or no relevant experience with the product, and fire officers remain conservative in their thinking on this.”

He adds, “The restrictions on mass timber usage are due to the interpretation of regulations. This means despite the knowhow and supply chain being in place, we are missing out on a huge opportunity with mass timber construction.”

Next Steps

Through the IGBC Mass Timber Construction Committee, John Casey and several like-minded technical experts have combined their resources with the IGBC to engage with the government on the benefits of mass timber and CLT.

“A small group of like-minded people for the industry came together to look at the barriers to CLT in Ireland and decided that the best route forward was to engage with the government under the auspices of IGBC, providing IGBC with technical back-up in any meetings that took place.”

This has led to a number of high-level meetings with ministers and senior civil servants to see if there is a way to break the impasse on the use of the material. Casey says that the Agrément certification requirement is a massive impediment to opening up the market. Also, Ireland needs to address the prohibition of the use of timber for buildings over three storeys.

“If the requirement for Agrément certification is confirmed, there will be no interest among regulators in allowing CLT to be used for the construction, and nothing will change. The longer this issue is not addressed, the harder it will be to achieve housing output and carbon reduction targets.

“The prohibition on the use of timber for buildings of heights above 10 metres also needs to be brought in line with EU building regulations.”

In Conclusion

John Casey has been actively involved in trying to open up the CLT market in Ireland for the past five years. And while it is a slow process, he says that in the past few months, the mass timber and CLT movement is gaining momentum.

“Mass timber is a sustainable and highly efficient building material. It is an established building system, and we have the technical skills to build with it.

“We have finally started to address the issues around its usage, and I am optimistic that we will soon reach a stage where civil servants and fire officers who make the decisions about its usage will have greater confidence about its many merits,” he concludes.

John Casey founded CORA in 2006. The consultancy has a staff of 28. CORA promotes a culture of creativity, innovation and quality in the firm, always striving to produce a better, more innovative and economical structural solution.

Low-carbon design solutions are an integral part of its service offering, and it has enabled many clients to achieve substantial carbon reductions in their developments. One project, currently on site, is reusing original steelwork from a building for a new extension.

Its portfolio includes the VHI extension on Abbey Street, Dublin; Barretstown Camp Pavilion, Co Kildare; Saint Luke’s Church office conversion, Dublin; West Cork Arts Centre, Skibbereen; and Windmill Quarter development in Dublin.

Its recent clients include Google, Facebook and DAA, as well as several blue-chip property development companies.