The premise of Octavia E. Bulter’s Xenogenesis trilogy—that an alien species survives by constantly manipulating its own DNA—is so subversive and fascinating that I recently found myself glued to its pages. In the narrative, when these aliens capture humans from their post-nuclear-war world and begin the process of merging with their DNA, issues of complicity, consent, and the ethics surrounding biomanipulation quickly compound. The novel, as Butler’s oeuvre generally does, revels in narrative ambiguity. To genetically merge, to literally become alien, is both a pathway to survival for the humans in captivity and the end of the human race—the aliens are both their savior and captor. The protagonist constantly shifts, forcing the reader to continuously reassesses their own biases and cultural binaries. As such, Butler’s writing “encourage[s] people to be critical thinkers and active agents in their own destinies,” as Lynell George explained in a recent New York Times essay.¹

Active agency in the world often involves adaptation, or the development of what theorist Chéla Sandoval calls “cyborg skills.” In stephanie mei huang’s interview with rafa esparza in this issue, huang explains that the cyborgian ability to “adapt and shapeshift” is intrinsic to any resistance. For his part, esparza has found that his experimentations in cyborgian practice constitute

an “embodied way of building a relationship to space, to people, [and] to objects”—its own kind of resistance in a Western culture that prioritizes individual success and survival over the communal.

Jessica Simmons’ essay on Tala Madani’s oft-painted “shit mom” character adds new commentary to a more abject vision of the cyborg. Simmons argues that the debased nature of shit mom is actually her escape route—by becoming shit, she also becomes fluid and nimble, liberating herself from patriarchal limitations.

Just as Butler’s narrative— written in the ’80s and set on the edge of apocalypse—is experiencing a cultural revival, Isabella Miller writes about how apocalyptic fascination has come back into vogue. Miller identifies an aesthetic language that she calls “the contemporary medieval”—the prevalent use of medieval imagery that is resurfacing in art and culture today. This, she argues, may have to do with our desire to address the “powerlessness we feel in an increasingly technologized and globalized world.”

It can be hard to be an active agent at the end of the world. But Butler shows us that there is no one way forward. Across this issue, writers and artists explore myriad pathways towards agency, including becoming cyborg, using objects to tell powerful stories, and exploring how abjection might not be so abject after all.

Lindsay Preston Zappas Founder & Editor-in-Chief48–63 Reviews

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio at Pitzer College Art Galleries

–Nick Earhart a time to tear and a time to mend at Wönzimer

–Donasia Tillery

Maria Maea at Murmurs

–Tina Barouti

The New Bend at Hauser & Wirth

–Isabelle Rust

Chris Warr at Phase Gallery

–Serena Caffrey (L.A. in London)

John Knight at Cabinet

–Rosa Tyhurst

65–92

Solid Art Services specializes in the installation, shipping, packing and storage of fine art. Offering unparalleled expertise and a passion for excellence, our team is ready to handle all your art-related needs with exceptional service and attention to detail.

office@solidartservices.com

www.solidartservices.com

Los Angeles Distribution: Atwater Village/ Silver Lake/Echo Park

Carlye Packer 2111 W. Sunset Blvd.

Marta 1545 W. Sunset Blvd.

Larder 3908 De Longpre Ave. No Moon LA 3137 Glendale Blvd.

Smart Objects 1828 W. Sunset Blvd.

Tyler Park Presents 4043 W. Sunset Blvd.

Umico Printing and Framing 3101 Glendale Blvd.

Chinatown/Boyle Heights Bel Ami 709 N. Hill St. #105

Charlie James 969 Chung King Rd.

FOYER-LA 970 N. Broadway St. #204

Human Resources 410 Cottage Home St.

LACA 709 N. Hill St. #104

NOON Projects 951 Chung King Rd.

Parrasch Heijnen Gallery 1326 S. Boyle Ave.

Sebastian Gladstone 944 Chung King Rd.

SOLDES 510 Bernard St.

Tierra del Sol Gallery 945 Chung King Rd.

The Fulcrum 727 N. Broadway #205

Wönzimer Gallery 341-B S. Ave. 17

Culver City/West Adams Anat Ebgi 2660 S. La Cienega Blvd.

Arcana Books 8675 W. Washington Blvd.

Blum & Poe 2727 S. La Cienega Blvd.

George Billis Gallery 2716 S. La Cienega Blvd.

Hashimoto Contemporary 2754 S. La Cienega Blvd., Suite B

Philip Martin Gallery 2712 S. La Cienega Blvd.

Shoshana Wayne Gallery 5247 W. Adams Blvd.

the Landing 5118 W. Jefferson Blvd.

The Wende Museum 10808 Culver Blvd.

Thinkspace Projects 4217 W. Jefferson Blvd.

Downtown Ace Hotel DTLA 929 S. Broadway

Artbook @ Hauser & Wirth 917 E. 3rd St.

Baert Gallery 1923 S. Santa Fe Ave.

Canary Test 526 E. 12th St., Unit C

Château Shatto 1206 Maple Ave. #1030

Cirrus Gallery 2011 S. Santa Fe Ave.

François Ghebaly 2245 E. Washington Blvd.

GAVLAK 1700 S. Santa Fe Ave. #440

ICA LA 1717 E. 7th St.

in lieu 1206 Maple Ave., Suite 903

JOAN 1206 Maple Ave. #715

Luis De Jesus Los Angeles 1110 Mateo St.

MOCA Grand Avenue 250 S. Grand Ave.

Monte Vista Projects 1206 Maple Ave. #523

Murmurs 1411 Newton St.

Nicodim Gallery 1700 S. Santa Fe Ave. #160

Night Gallery 2276 E. 16th St.

Over the Influence 833 E. 3rd St.

Patricia Sweetow Gallery

1700 S. Santa Fe Ave. #351

Royale Projects

432 S. Alameda St.

The Box

805 Traction Ave.

Track 16 1206 Maple Ave. #1005

Vielmetter Los Angeles 1700 S. Santa Fe Ave. #101

Wilding Cran Gallery 1700 S. Santa Fe Ave. #460

Eagle Rock/Cypress Park

BOZOMAG 815 Cresthaven Dr.

Gattopardo 2626 N. Figueroa St., Unit C

la BEAST gallery 831 Cypress Ave.

OXY ARTS 4757 York Blvd.

Historic South Central/ Long Beach Angels Gate Cultural Center 3601 S. Gaffey St.

Long Beach City College 4901 E. Carson St.

SELA Art Center 4350 E. Gage Ave., Unit C

South Gate Museum and Art Gallery 8680 California Ave.

Sow & Tailor

Torrance Art Museum 3320 Civic Center Dr.

USC Fisher Museum of Art 823 W. Exposition Blvd.

Hollywood/Melrose albertz benda 8260 Marmont Ln.

Diane Rosenstein 831 N. Highland Ave.

Harper’s Gallery 8115 Melrose Ave.

Helen J Gallery 929 Cole Ave.

Lauren Powell Projects 5225 Hollywood Blvd.

MAK Center for Art and Architecture 835 N. Kings Rd.

Make Room Los Angeles 5119 Melrose Ave.

Matthew Brown Los Angeles 633 N. La Brea Ave., Suite 101

Meliksetian | Briggs 313 N. Fairfax Ave.

Morán Morán 641 N. Western Ave.

Moskowitz Bayse 743 N. La Brea Ave.

Nino Mier Gallery 1107 Greenacre Ave.

Nonaka-Hill 720 N. Highland Ave.

Rele Gallery LA 8215 Melrose Ave.

Sean Kelly 1357 N. Highland Ave.

Sebastian Gladstone 5523 Santa Monica Blvd.

Shulamit Nazarian 616 N. La Brea Ave.

Simchowitz 8255 Beverly Blvd.

STARS 1659 N. El Centro Ave.

Steve Turner 6830 Santa Monica Blvd.

Stroll Garden 7380 Beverly Blvd.

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery 1010 N. Highland Ave.

The Aster LA 1717 Vine St.

The Hole 844 N. La Brea Ave.

The LODGE 1024 N. Western Ave.

Various Small Fires 812 Highland Ave.

MacArthur Park/Pico-Union as-is.la 1133 Venice Blvd.

Commonwealth & Council 3006 W. 7th St. #220

Hannah Hoffman 2504 W. 7th St., 2nd Floor

New Low 705 S. Rampart Blvd.

O-Town House 672 S. Lafayette Park Pl.

The Poetic Research Bureau

2220 Beverly Blvd.

Mid-City Chris Sharp Gallery

4650 W. Washington Blvd.

Harkawik

1819 3rd Ave.

Hunter Shaw Fine Art

5513 W. Pico Blvd.

Lowell Ryan Projects 4619 W. Washington Blvd.

Matter Studio Gallery 5080 W. Pico Blvd.

OCHI 3301 W. Washington Blvd.

Park View / Paul Soto 2271 W. Washington Blvd.

r d f a 3209 W. Washington Blvd.

Mid-Wilshire 1301 PE 6150 Wilshire Blvd.

Anat Ebgi 6150 Wilshire Blvd.

Craft Contemporary 5814 Wilshire Blvd.

David Kordansky Gallery 5130 W. Edgewood Pl.

Hamzianpour & Kia 5225 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 212

One Trick Pony 1051 S. Fairfax Ave.

Pace 1201 S. La Brea Ave.

Praz-Delavallade 6150 Wilshire Blvd.

Roberts Projects 442 S. La Brea Ave.

SPRÜTH MAGERS

5900 Wilshire Blvd.

Pasadena/Glendale

ArtCenter College of Design 1700 Lida St.

Feminist Center for Creative Work 1800 S. Brand Blvd., Suite 111

Junior High 603 S. Brand Blvd.

The Armory Center for the Arts 145 N. Raymond Ave.

The Pit 918 Ruberta Ave.

Office Space Burbank 1431 N. Lincoln St.

Westside 18th Street Arts 3026 Airport Ave.

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center 681 Venice Blvd.

D2 Art 1205 N. La Brea Ave.

Del Vaz Projects 259 19th St.

Five Car Garage

L.A. Louver 45 N. Venice Blvd.

L E M A X I M U M 2525 Lincoln Blvd.

Laband Art Gallery at LMU 1 Loyola Marymount University Dr.

Marshall Contemporary 2525 Michigan Ave. #A6

Paradise Framing 3626 W. Slauson Ave.

Von Lintel 2525 Michigan Ave., Unit A7

Westwood/Beverly Hills CLEARING

M+B 612 N. Almont Dr.

UTA Artist Space 403 Foothill Rd.

Non-L.A.

Art & Bodega (Claremont, CA)

BEST PRACTICE (San Diego, CA)

Bread & Salt (San Diego, CA)

Beverly’s (New York, NY)

Bortolami Gallery (New York, NY)

Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY)

DOCUMENT (Chicago, IL)

Et al. (San Francisco, CA)

Left Field (Los Osos, CA)

Mandeville Art Gallery, UC San Diego (San Diego, CA)

Minnesota Street Project (San Francisco, CA)

Mrs. (Queens, NY)

OCHI (Ketchum, ID)

Office Space (Salt Lake City, UT)

Oolong Gallery (Solana Beach, CA)

Santa Barbara City College (Santa Barbara, CA)

The Print Party (Pittsburgh, PA)

University Art Galleries, UC Irvine (Irvine, CA)

Verge Center for the Arts (Sacramento, CA)

Libraries/Collections

Bard College, Center for Curatorial Studies Library (Annandale-on-Hudson, NY)

CalArts (Valencia, CA)

Center for the Arts, Wesleyan University (Middletown, CT)

Charlotte Street Foundation (Kansas City, MO)

Cranbrook Academy of Art (Bloomfield Hills, MI)

Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Research Library (Los Angeles, CA)

Marpha Foundation (Marpha, Nepal)

Maryland Institute College of Art, The Decker Library (Baltimore, MD)

Midway Contemporary Art (Minneapolis, MN)

Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, Emerging Leaders in the Arts (Santa Barbara, CA)

Northwest Nazarene University (Nampa, ID)

NYS College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Scholes Library (Alfred, NY)

Pepperdine University (Malibu, CA)

Point Loma Nazarene University (San Diego, CA)

Room Project (Detroit, MI)

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, John M. Flaxman Library (Chicago, IL)

Skowhegan Archives (New York, NY)

Sotheby’s Institute of Art (New York, NY)

Telfair Museum (Savannah, GA)

The Baltimore Museum of Art Library & Archives (Baltimore, MD)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library (New York, NY)

University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA)

University of San Diego (San Diego, CA)

USC Fisher Museum of Art (Los Angeles, CA)

Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN)

Whitney Museum of American Art, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library (New York, NY)

Yale University Library (New Haven, CT)

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles is a quarterly magazine, online art journal, and podcast committed to being an active source for critical dialogue in and around Los Angeles’ art community. Carla acts as a centralized space for art writing that is bold, honest, approachable, and focused on the here and now.

Founder and Editor-in-Chief

Lindsay Preston Zappas

Contributing Editor

Catherine Wagley

Managing Editor

Erin F. O’Leary

Editorial & Administrative Assistant

Alitzah Oros

Graphic Designer

Satoru Nihei

Copy Editors

Rachel Paprocki

Erin F. O’Leary

Social Media Manager

Jonathan Velardi

Translator

Edita.us

Color Separations

Echelon, Los Angeles

Submissions

For submission guidelines, please visit contemporaryartreview.la/submissions. Send all submissions to submit@contemporaryartreview.la.

Inquiries

For all other general inquiries, including donations, contact us at office@contemporaryartreview.la

Advertising

For ad inquiries and rates, contact ads@contemporaryartreview.la

W.A.G.E.

Carla pays writers’ fees in accordance with the payment guidelines established by W.A.G.E. in its certification program.

Copyright

All content © the writers and Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles.

Social Media

Instagram: @contemporaryartreview.la

Cover Image

Kira Freije, permanence of a sacred tongue (2022). Stainless steel, cast aluminum, and cotton, 48 × 25.5 × 38.5 inches. © Kira Freije. Image courtesy of the artist and The Approach, London. Photo: Michael Brzezinski.

Contributors

Lindsay Preston Zappas is an L.A.-based artist, writer, and the founder and editor-in-chief of Carla. She is an arts correspondent for KCRW and visiting faculty at Harvey Mudd College. She received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art and attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2013. Recent solo exhibitions include those at the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY), Ochi Projects (Los Angeles), and City Limits (Oakland).

Catherine Wagley writes about art and visual culture in Los Angeles.

Erin F. O’Leary writes about and makes photographs in Los Angeles.

Rachel Paprocki is a writer, editor, and student of library science who lives and bikes in Los Angeles.

Alitzah Oros is an art historian based in Los Angeles.

Satoru Nihei is a graphic designer.

Jonathan Velardi is a social media consultant and strategist. He advises organizations and individuals in art, architecture, and design on content creation, storytelling, and accessibility connected to online behavioral landscapes. Select accounts include the Glass House and The Huntington Library.

Membership

Carla is a free, grassroots, and artist-led publication. Club Carla members help us keep it that way. Become a member to support our work and gain access to special events and programming across Los Angeles.

Memberships are tax-deductible. To learn more, visit: join.contemporaryartreview.la.

Carla is a free, independent, grassroots, and artist-led publication. Club Carla members help us keep it that way.

Join our diverse and vibrant arts community, get special access to L.A. art events and programming, and support Carla’s dedication to critical arts dialogue.

join.contemporaryartreview.la

Simone Forti, Planet , PS1, Long Island City, NY, 1976, performed with music by Peter Van Riper.

Pictured: Simone Forti and Sally Banes.

Photo by Peter Moore. Courtesy of The Box, Los Angeles.

Simone Forti, Planet , PS1, Long Island City, NY, 1976, performed with music by Peter Van Riper.

Pictured: Simone Forti and Sally Banes.

Photo by Peter Moore. Courtesy of The Box, Los Angeles.

Tala Madani, Shit Mom Animation (video still) (detail) (2021). Single-channel video with color and sound, 7 minutes and 45 seconds. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tala Madani, Shit Mom Animation (video still) (detail) (2021). Single-channel video with color and sound, 7 minutes and 45 seconds. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tala Madani’s paintings and animations drip with unmentionable visions: enormous erupting penises that overwhelm their handlers, men engorging and cavorting with frosted cakes, wanton imbeciles ogling young girls. In one particularly potent animation, a growing embryo watches from inside the womb as a spectral projection of the world’s violent history unfolds before its virgin eyes. In response, the fetus wields a hidden pistol and shoots at this uterine cinema, wounding its mother’s body, now marred with luminescent, confetti-like holes. While not explicitly a commentary on matricide, The Womb (2019) represents one of Madani’s many references to the ways that patriarchal cycles of violence ravage the maternal figure.

Patriarchs generally account for Madani’s most recognizable subjects: These bald, unkempt, fleshy, and semi-naked middle-aged men defile her canvases with their bizarre and maniacal pursuits, suggesting deranged carnivals of noxious hypermasculinity. Within this context, her depictions of more innocent characters, such as children and babies, deliver fresh discomforts. In Blackboard (Further Education) (2021), a line of schoolchildren marches into the jaws of a prone giant and emerges from its anus as graduates clothed in caps and gowns, a damning view of the pedagogical obedience demanded by our contemporary educational institutions. In the series Abstract Pussies (2013–19), a giant girl—a young

child—sits with her legs agape as a gaggle of miniature men gather at her feet and attempt to peer beneath her skirt. While the male gawkers’ twisted antics vary between the paintings (in one, they all villainously don 3-D glasses), their backs almost always face the viewer, framing their vantage point as our own. This shared perspective implicates us in their exploits, a grating realization that violates the decorum of our assumed neutrality as viewers —a brilliant subversion on the part of the artist. Pointed in their wickedness, Madani’s unholy tableaus allegorize the rampant perversions of our patriarchal culture, supposing our own complicity.

Despite their lurking dangers, Madani’s paintings revel in their materiality, offering interludes of tangible pleasure that dually blunt and amplify their enclosed horrors. Often, this haptic handling of paint actually functions as the key to the work’s discomfiting tone: Her slick, goopy marks frequently reveal—or rather, become—spurting fountains of semen, blood, breastmilk, skin, urine, and feces, firmly situating the abject as a key component to the language of her work. In philosopher Julia Kristeva’s eminent 1980 text on abjection, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, she conceives of the abject (particularly with regard to the body) as that which has been cast off and displaced from its original subjecthood, disrupting its meaning. Our encounters with the abject, according to Kristeva, arouse psychologically dissonant states of familiarity, unfamiliarity, attraction, and repugnance—like beholding a corpse or an open wound.¹ Here, by rendering the viscous byproducts of the body as luscious, painterly gestures, Madani coaxes the viewer into this potent territory of abjection, severing the self from its carnal blueprint and commingling aesthetic arousal with repulsion.

Of the range of fluids that Madani reproduces in her work, it is her depiction of feces, arguably the vilest of the bodily excretions, that commands the most conceptual attention. In her series of paintings and animations,

Shit Mom (2019–present), Madani disrupts simple, earnest scenes of motherhood by deconstructing the mother’s body, rendering her with unbecoming smears of dismal brown paint—a material surrogate for shit. In fact, this maternal figure is so gesturally laden with feces that she becomes excrement: Her physical body mercilessly dissolves into the muck, an exorcism that recasts her as a shadowy, scatological form. Despite her abject swampiness (she often pools into drippy piles before rearticulating herself), this mothershaped being continues to enact the sacred duties of motherhood. Although this narrative accommodates a textbook Freudian reading, which posits the mother as an abject figure necessarily cast off by the child in the creation of their discrete self, Madani’s shit mom instead interrogates, through a feminist lens, the condition of motherhood as both a patriarchal institution and a deeply intimate existential state. (Indeed, shit mom doesn't actually “appear” gendered; in Madani’s series, in which caregiving status is up for examination, female identity is not a prerequisite for being a mother.) These works also exhibit a tender, comical, and sometimes biting reverence for the hermetic and largely uncategorizable psychosocial experience that motherhood entails—an experience often opined and more often misunderstood within wider cultural discourse.

Motherhood is a paradoxical enigma, a contingent state of being that accounts for one of the most extraordinary yet unblinkingly ordinary phenomena of human existence. It is often mired in grueling mundanity, its complexities flattened or dismissed. A mother who gives voice to these dichotomies, or who struggles to adhere to the beneficent image of a Madonna, becomes a taboo—she’s a shit mom.

At the beginning of Adrienne Rich’s totemic treatise on motherhood, Of Woman Born (1986), she scrutinizes this dilemma with the astute observation that “we know more about the air we breathe, the seas we travel, than about the nature and meaning of motherhood.”²

This denigration, Rich emphasizes, stems from the historically persistent, male-driven omission of motherhood as a topic of scholarship and meaningful philosophical discourse. Despite being firmly interwoven with the patriarchal social order, motherhood is an island— its contours form in quiet obscurity, emanating from the primal bond that comprises the inner sanctum of the mother-child relationship. Perhaps this accounts for the isolation of Madani’s shit mom, depicted either with her children as her sole companions or completely alone.

Echoing this isolation, Madani’s soon-to-close mid-career retrospective at MOCA, Biscuits, confines most of the Shit Mom series to its own small gallery, a cloistered space sheathed in a verdant leafy wallpaper—an adornment that domesticates the white cube—which the artist has sullied with brushstrokes of metaphorical shit. This feces-besmirched installation mirrors Shit Mom Animation (2021), which depicts a dung-bound maternal figure wandering alone in an elaborate house, leaving a trail of brown marks clinging to every surface she grazes. While these indexical traces point to the dangers of her imperfections—every shitty parental mishap might be indelibly cataloged by a noisy social choir, or worse, by the child’s own psyche— these gestures also posit the mother as a mark-maker, a progenitor of life and culture. Despite this life-bestowing power, the tendencies of patriarchal culture nonetheless seep through these stool-smeared walls, weaponizing shit mom’s alleged imperfections as generators of maternal guilt and self-doubt, feeding the mother’s isolation, and poisoning potential articulations of maternal power— collective articulations, in particular. Thus, as shit mom hovers between abject form and formlessness, she also inhabits the liminal space of perpetual waiting—waiting as she breastfeeds (Nature Nurture, 2019), waiting as the children play (Shit Mom [Recess], 2019)—and she does so alone. Inherently static, the act of waiting freezes forward momentum and keeps the mother

Tala Madani, Biscuits (installation views)(2022–23) . Images courtesy of the artist and The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

Tala Madani, Biscuits (installation views)(2022–23) . Images courtesy of the artist and The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

entangled in the narrow confines of domesticity. In her potent 2007 essay, “Feminist Mothering,” Andrea O’Reilly asserts the political implications of this socially conditioned, inwardfacing conception of motherhood.

“In defining mothering as private and nonpolitical work,” she writes, “patriarchal motherhood restricts the way mothers can and do affect social change.…The dominant ideology also reserves the definition of good motherhood to a select group of women.”³ Privileging social compliance and whiteness, this selective notion of “good” motherhood, of course, stems from conservative definitions of maternity and femininity, meaning that single mothers, impoverished mothers, mothers of color, and mothers with multiple jobs are most susceptible to being derided as shit moms. Referencing this reality, bell hooks advocated for the collective, intersectional harnessing of maternal power, positing what she calls the “homeplace,” the realm of the mother, as a “ site of resistance,” an antidote to “the brutal harsh reality of racist oppression, of sexist domination.”⁴

Madani deftly anthropomorphizes the insidious oppression that O’Reilly and hooks invoke in a trio of works displayed together at MOCA: Shit Mom (Hammock), Pinocchio Rehearsal, and Pinocchio’s Mother (all 2021), small canvases whose scenes unfold in a wood-lined, cabin-like room. In Shit Mom (Hammock), our fecal friend indulges in a moment of childless respite—a highly criticized act—by reclining in a hammock, her body discharging drips and stains on the floor beneath her. In Pinocchio Rehearsal, the forms of six ominously smiling men protrude, ghost-like, from the walls of the same room, their noses elongated—presumably with deceit. Lastly, in Pinocchio’s Mother, shit mom kneels and clutches her child, who is dressed as Pinocchio, as the same phantom patriarchs loom and glare from the wall above in an anxious, voyeuristic drama. Here, Madani suggests that, whether seen or unseen, the malignant forces that define the

Tala Madani, Shit Mom (Feedback) (2021). Oil on linen, 72 × 108 inches. Collection of the Long Museum, Shanghai. Image courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Tala Madani, Shit Mom (Feedback) (2021). Oil on linen, 72 × 108 inches. Collection of the Long Museum, Shanghai. Image courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

patriarchal institution of motherhood will infiltrate even the most quotidian of private moments, and before long, the child itself will absorb and mimic its culture’s heteronormative behaviors.

As an unapologetically abject figure, shit mom can ultimately be thought of as a radical rejection of the patriarchy-tinged conception of motherhood that our culture propagates. Indeed, Madani initially conceived of shit mom through a gestural act of negation: In refusing to adopt a saccharine depiction of a Madonna and child—and in a forceful rejection of the art historical precedent for the treatment of the nude female form—she purposefully smeared a painting of a mother and baby, thus birthing shit mom.⁵ In nullifying the body, she garners control of it. (In the words of Rich again, “the body has been made so problematic for women that it has often seemed easier to shrug it off and travel as a disembodied spirit.”)⁶

In this vein, shit mom’s disavowal of the body can be understood as a strategy of self-preservation. In her scatological disembodiment, she becomes a physically mercurial and indocile figure, no longer woundable and thus powerful in her repugnance.

As an artistic and literary device, excrement has a rich history of deployment as a symbol of social disruption, from the work of James Ensor, Mike Kelley, and Paul McCarthy to Mary Kelly, whose influential work Post-Partum Document (1973–79) incorporates her son’s soiled diapers as a testament to the dirty labor inherent to both mothering and art-making. Feces represent the paragon of abjection, confusing the barrier between waste and renewal, life and death, and reminding us of our base animality. In a short essay on the scatological, artist Lenore Malen quotes the French psychoanalyst Janine ChasseguetSmirgel in suggesting that “‘all that is taboo, forbidden or sacred is devoured by the digestive tract…in order to reduce it to excrement.’” Malen defines this process as the ultimate “abolition of boundaries.”⁷ Shit, after all, accounts for the most fertile soil, catalyzing the

decomposition of old matter—perhaps a metaphorical dissolution of conservative boundaries and staid taboos—and fostering the new. By presenting the maternal figure as a strangely beautiful, putrid pile of feces—one that degenerates and regenerates—Madani severs the intimate lived reality of motherhood from patriarchal oversight, allowing the mother to revel in her innate complexities and reform her body, and parental ethos, to mirror her own feminist decree. Ultimately, this liberatory gesture extends from the personal to the collective. In considering the poetic implications of the collective experience of maternity, poet Alicia Ostriker describes a mother’s metamorphosis “from being a private individual self to being a portion of something else” as a totemic realization: “I had the sense of being below the surface, where the islands are attached to each other.”⁸ If we posit motherhood as such an island—a space defined by its isolation—the understanding that it connects to a larger ecosystem can be revolutionary.

Jessica Simmons-Reid is an artist and writer based in Los Angeles and Joshua Tree.

1. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), https://www.thing.net/~rdom/ucsd/Zombies/ Powers%20of%20Horror.pdf.

2. Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (New York: W.W. Norton, 1986), 11.

3. Andrea O’Reilly, “Feminist Mothering,” in Maternal Theory: Essential Readings, ed. Andrea O’Reilly (Toronto: Demeter, 2007), 801–802.

4. bell hooks, “Homeplace (a site of resistance),” in O’Reilly, Maternal Theory, 267.

5. Ben Luke, “A brush with… Tala Madani,” February 3, 2021, in The Art Newspaper Podcast, produced by Julia Michalska, David Clack, Aimee Dawson, Henrietta Bentall, and Kabir Jhala, podcast, 55 minutes, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/02/03/ a-brush- with-tala-madani.

6. Rich, Of Woman Born, 40.

7. Lenore Malen, “Postscript: An Anal Universe,” Art Journal 52, no. 3 (Autumn, 1993): 79–81.

8. Alicia Ostriker, “A Wild Surmise: Motherhood and Poetry,” in Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood, ed. Moyra Davey (New York: Seven Stories, 2001), 156.

Tala Madani, Pinocchio’s Mother (2021). Oil on linen, 16.25 × 12 × 1 inches. Private collection, Monaco. Image courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Tala Madani, Pinocchio’s Mother (2021). Oil on linen, 16.25 × 12 × 1 inches. Private collection, Monaco. Image courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

In 1850, on a plantation in South Carolina, Harvard University zoologist Louis Agassiz created nude daguerreotypes of seven enslaved individuals without their consent. He was attempting to gather evidence to prove his racist theory of “polygenesis,” which posited that Black and white people came from separate species.¹ In 2010, Tamara Lanier, a descendant of two of the photographed individuals, named Renty and Delia, learned that Harvard University’s Peabody Museum retained the daguerreotypes of her relatives, and in 2019, she initiated a lawsuit against the university for their return to the family line. Lanier held that Harvard should return the daguerreotypes of her ancestors to her because they had been obtained through unclean hands. This wasn't a farfetched argument because it's arguable that the images constituted the fruits of robbery. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court rejected Lanier’s claim to the property in 2022 but did allow her to sue the school for negligent and reckless infliction of emotional distress, in large part because of the “horrific” conditions that surrounded the daguerreotypes’ production.²

The outcome of Lanier v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, and the story behind Lanier’s struggle, expose a devastating history often ignored by mainstream society until the racial revolution that began in the 2010s and crested during the protests of 2020. Like Lanier, the curators of LACMA’s remarkable exhibition Afro-Atlantic Histories recognize the importance of imagery and artifacts in telling

the story of Black enslavement. Moreover, the show arrives at a time when conversations around these issues are becoming more mainstream, and as activists, artists, and curators respond to this history through aesthetic and political reclamations. Displaying artworks and objects that address slavery and its influences in Latin America, the Caribbean, the United States, and Europe, Afro-Atlantic Histories spans from the seventeenth century to the present. The exhibition comes to Los Angeles by way of São Paulo, Brazil—the show first appeared in 2018 as Histórias Afro-Atlânticas at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) and the Instituto Tomie Ohtake, before traveling to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Dallas Museum of Art; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. At LACMA, it has been adapted to the Resnick Pavilion by curators Rita Gonzalez and José Luis Blondet, who introduced works from their collection, including pieces L.A.-based artists Betye Saar, Maya Stovall, and Todd Gray, to the more than 100 pieces in the original exhibition. “The show is about slavery throughout the Americas, not just in the U.S., as we typically talk about it here, in this country,” Gonzalez told me at the press preview.

The curators divided the show into sections, such as Maps and Margins, which graphs the forced passage of enslaved people from their homes to their bondage. Cartographies reveal sites of embarkation and disembarkation in North and South America (Chesapeake and Bahia) and Africa (Senegambia, Sierra Leone, and the Gold Coast).

In a painting by Kerry James Marshall, Voyager (1992), a woman stands at the prow of a slave ship. Silvery lines limn her onyx features, revealing a high, wide brow and a firmly set mouth. The ship’s name is Wanderer, a reference to the penultimate schooner to bring slaves to the United States, trafficking 409 survivors to Georgia in November 1858. This scene is fraught, but Marshall is not interested

in flattening or objectifying his subjects. Fresh insights emerge also from works such as Saar’s I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break (1998). The installation consists of a vintage ironing board, a flat iron attached to a shackle and chain, and a bedsheet embroidered with the initials KKK and hanging on a line with clothespins. On the ironing board, Saar printed a diagram of the Brookes, a notorious eighteenth-century British slave ship. The title gives us access to the mantras of Black women who have resisted oppression throughout the centuries.

Another room hosts work under the category of Enslavement and Emancipation, which exposes the horrors of captivity. Arthur Jafa’s sculpture Ex-Slave Gordon (2017) replicates an infamous 1863 carte-de-visite portrait of an enslaved man. A postcard widely circulated by abolitionists, the image is now known as The Scourged Back. Jafa made his version of gunmetal-colored vacuum-formed plastic, which topographically displays the scars and welts that cascaded down Gordon’s spine, offering an anatomical model of the man’s anguish. Nearby, Nona Faustine’s From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth (2013) also brings home how U.S. enslavement assailed the physicality and worth of Black people: In the photograph, Faustine stands nude (but for a pair of white shoes) on Wall Street, the stage of the New York City’s first official human market.

The Black American artist Imani Jacqueline Brown has observed that mass media often focuses on the torment of Black people, creating “an overflowing archive of fetishized suffering.”³ Indeed, in different hands, Afro-Atlantic Histories could have grown into a livid spectacle. Avoiding the trap of portraying enslaved people as abject victims, the exhibition’s organizers delve into their and their descendants’ subjectivity, delivering a nuanced picture of individual experiences of subjugation and resistance to it.

Several works in the exhibition prompt viewers to do the work of

interpretation independently, such as Maya Stovall’s 1526 (NASDAQ: FAANG), no. 1 (2019). This installation quietly displays the number 1526 in pale yellow neon, while the didactic reveals a complex mélange of materials: “archives, buttercream neon, and FAANG fonts.” The numeral refers to the year of the first recorded slave revolt in what became the U.S., and “buttercream neon” points to the triangular trade route, in which sugar was often exchanged for slaves. FAANG is the stock market acronym for NASDAQ big-hitters Meta (formerly Facebook), Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Alphabet (Google’s parent company). Stovall’s meaning, once it arrives, hits like a brick: Slavery created wealth that still drives values today.

Stovall’s neon is a pivot point in the show. The worldwide epiphany on these issues resounded in 2020, but old white supremacist structures of memory had started to crumble before then. In 1989, U.S. Representative John Conyers (D-Michigan) introduced House Resolution 40 (H.R. 40), which would set up a commission to study reparation proposals for African Americans. The bill languished despite the fact that Conyers sponsored the Act in each Congress for the following nearly 30 years of his career. But in recent years, a wider swath of people has begun to awaken to the idea of restitution, what Malcolm X once called “payday—retroactive.”⁴

In 2014, The Atlantic published Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case for Reparations,” in which he assessed the U.S. as a “regime that elevated armed robbery to a governing principle.”⁵ In December 2022, U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), the sponsor of the current iteration, urged President Biden to pass H.R. 40 via executive order.⁶

This movement is happening globally, too—in 2007, Guyana called on European nations to pay reparations for slavery. In 2011, Antigua and Barbuda followed suit. Back in the U.S., members of the public also began to demand the recoup of what they’d

lost. For example, in the 2010s, many individuals and groups worked to take back their communities by acts of damnatio memoriae, calling for the removal of Confederate monuments to the likes of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and J.E.B. Stuart.⁷ And at the time of publication, L.A.’s own Reparations Advisory Commission (established June 2021) prepares to issue recommendations for addressing disparities affecting the city’s Black residents.⁸

Afro-Atlantic Histories simultaneously offers a memorial space for community healing, describes the big picture of the Black Atlantic, and takes part in this political moment. Interestingly, when I asked Gonzalez if LACMA had invited L.A.’s Commission members for a viewing, she said the museum had not done so. I felt momentarily disappointed. But then, I wondered about my own political expectations of arts institutions. Does LACMA have an obligation to press for social change directly?

Perhaps they do. Museums, which have long played a historical role in the plunder of people of color’s bodies and cultural products, can owe special moral and legal duties to repair the injustices of the past.⁹ While Harvard’s Peabody neglected to do right by Lanier, some cultural organizations have made strides in this direction, such as The Brooklyn Museum, which repatriated preHispanic artifacts to Costa Rica in both 2011 and 2020.¹⁰ Arts institutions find themselves grappling with a paradigm shift regarding their responsibilities to historically dominated peoples, and, within this moment, the possibility of LACMA serving as a container for active community reparations dialogues is a heady one.

For now, Gonzalez’s and Blondet’s passionate curation has laid the table, and it is up to the public to attend, remember, critique, and consider our next steps. The labor that the artworks require of their audience is not just aesthetic, but political. The show demands that we do the work. In 2019,

Tamara Lanier responded to two daguerreotypes in a museum’s collection with legal action. Afro-Atlantic Histories—or any one exhibition for that matter—is clearly not enough to repair the injustice of slavery. Only many continued acts of good faith, the redistribution of wealth, and communal transformation can begin to remedy the outrages so ably documented by the artists represented here. The painful revelations of exhibitions such as this one challenge viewers on both personal and social levels, and thus constitute the first step toward a global reckoning.

1. Yxta Maya Murray, “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried: Carrie Mae Weems’ Challenge to the Harvard Archive,” Harvard Unbound 8 (2012), 1–78.

2. Isabella B. Cho and Brandon L. Kingdollar, “Mass. Supreme Court Allows Emotional Distress Claim Against Harvard to Proceed in Suit Over Photos of Enslaved People,” The Harvard Crimson, June 24, 2022, https:// www.thecrimson.com/article/2022/6/24/laniersupreme-court-remanded/.

3. Imani Jacqueline Brown, “The Remote Sense of Disintegration,” 2020, MPEG video, 5:59, https:// imanijacquelinebrown.net/The-Remote-Sensation-ofDisintegration.

4. Quoted in Murray, “From Here I Saw,” 69.

5. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/ magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-forreparations/361631/.

6. Gina Castro, “Reparations Leaders Demand Biden Act on H.R. 40,” Evanston Round Table, December 3, 2022, https://evanstonroundtable.com/2022/12/03/ state-federal-reparations-leaders-demand-presidentbiden-enact-hr-40/.

7. “Charlottesville takes down Robert E. Lee statue that sparked rally.” BBC, July 10, 2021, https://www.bbc. com/news/world-us-canada-57788220/.

8. Reparations Advisory Commission,” Civil and Human Rights and Equity Department, https:// civilandhumanrights.lacity.org/commissions/ reparations-advisory-commission/.

9. See, e.g., the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act 25 U.S.C. §3005(a) and §3001(3)(D) (2000).

10. Isis Davis-Marks, “Brooklyn Museum Returns 1,305 Pre-Hispanic Artifacts to Costa Rica,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 8, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag. com/smart-news/brooklyn-museum-returns-more-1300objects-costa-rica-180978122/.

Arthur Jafa, Ex-Slave Gordon (2017). Vacuum-formed plastic, 57 × 44 × 9 inches. Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of R.H. Defares. Image courtesy of the artist and LACMA.

Arthur Jafa, Ex-Slave Gordon (2017). Vacuum-formed plastic, 57 × 44 × 9 inches. Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of R.H. Defares. Image courtesy of the artist and LACMA.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Dressing for Windows/ Dressing for Altitude/ Dressing for Pleasure (detail) (2022).

Fighter jet seat, bronze statue, stainless steel barrel cart, leather jacket, meat hooks, conveyor belt, pulleys, and hardware, 144 × 87 × 150 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Dressing for Windows/ Dressing for Altitude/ Dressing for Pleasure (detail) (2022).

Fighter jet seat, bronze statue, stainless steel barrel cart, leather jacket, meat hooks, conveyor belt, pulleys, and hardware, 144 × 87 × 150 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Elaine Cameron-Weir’s recent exhibition at Hannah Hoffman gallery, Exploded View / Dressing for Windows, enmeshed the old with the new and the sacred with the profane—or at least, with the grim, grimy, and secular. Disparate found objects were stripped of their original functions in favor of new forms. Four counterweighted sculptural installations resembled, as the exhibition’s title would suggest, department store window product displays. Comprising objects as various as stainless steel barrels, conveyor belts, and bronze reliefs depicting Jesus’ crucifixion, the assemblages cultivated a kind of junkyard mysticism in which the hypermodern conspired with the neomedieval.

A peculiar combination of anachronism and apocalypticism pervaded the exhibition. Objects invoking the Middle Ages were rendered equal to the detritus of modernity, as though the world envisioned by Cameron-Weir would emerge only after the “end times,” when all that remains is material ruin. In these constructions, time felt out of joint: Glass magic lantern slides depicting premodern religious imagery, such as cathedrals and stained glass, mingled with images of modern sites of violence and destruction. CameronWeir is one of several contemporary artists experimenting with anachronism, combining symbols of a medieval past with those lifted from contemporary life—what we might call the “contemporary medieval.” These artists’ invocations of the past offer new ways to think through contemporary existential laments surrounding

Isabella Millertechnology, consumer culture, and environmental devastation.

In the 1980s, Italian philosopher and writer Umberto Eco linked neomedieval style with apocalypticism. For Eco, the modern fascination with the Middle Ages visible across twentieth-century popular art and architectural forms (Hearst Castle in central California, the early films of Ernst Ingmar Bergman, mass-market paperbacks like Arthur H. Landis’ 1976 A World Called Camelot and J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1955 The Return of the King) might be ascribed to the era’s troublesome social, political, and economic dynamics, such as the rise of fascism and neoliberalism’s increasing hold on global economic and political structures. These circumstances mirrored changes that burgeoned in the medieval era between 1100 and 1500, when capitalist economies began to supersede feudalism, nation-states became primary political units, and heresy (the culture war of yesteryear) was rendered a punishable offense.

Judgment Day was a cornerstone of medieval ideology, and because its imminent arrival was perpetually deferred, it always loomed large in the medieval imaginary. Eco writes: “These Middle Ages […] still accompany us and will continue to do so, until midnight of the Day After. Source of so many insanities, [the Middle Ages] remain however as a permanent warning. Sometimes it is not so medieval to think that perhaps the end is coming and the Antichrist, in plainclothes, is knocking at the door.”¹ In the mid-late twentieth century, medieval narratives, atmospheres, and archetypes became especially enticing tools to register an enduring doomsday anxiety. According to Eco, we were “dreaming the Middle Ages”²—a dream from which we’ve not yet woken. Caught between the environmental, political, and economic crises of today, it’s not difficult to imagine humanity’s imminent demise.

Just as Eco saw traces of medieval fascinations across pop culture in his lifetime, over the past few years, neomedievalism has

made a pronounced resurgence, saturating contemporary cultural production with tales of nuns, knights, courtly love, and mortal sin. From Jos Charles’ poetry collection feeld (2018), Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel Lapvona (2022), and Lauren Groff’s novel Matrix (2021), to films like Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel (2021), David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021), and Robert Eggers’ The Northman (2022), popular interest in totalizing (if not always historically accurate) medieval worldbuilding seems to be more widespread than ever. But as the genre increasingly appears in visual art, its relationship to anachronism takes on a slightly different form. From the commedia dell’arte³ masks present in the paintings of TARWUK, Joel Dean, Adam Alessi, and Victor Boullet, to the sculptures of Kira Freije, Rochelle Goldberg, and Cameron-Weir, these and other artists strategically appropriate icons and symbols invoking the medieval, rather than attempting to immerse the viewer in a contained narrative fantasy of another historical moment. In other words, they emphasize anachronism to reveal something about our current world.

Like Cameron-Weir, Goldberg and Freije often work with imagery rooted in medieval Catholic art and architecture that nevertheless resonates in our present historical moment. In Goldberg’s Intralocuters series (2017–present), for instance, she works primarily with the “Composite Magdalene” of Roman Catholic theology, specifically Saint Mary of Egypt, a former prostitute who, upon visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, ventured into the desert to live devoutly in solitude.⁴ Across the series, Goldberg renders Mary of Egypt as one with her environment through organic and inorganic materials—ceramic, steel, wood, human hair, animal fur, and feathers. This depiction of Mary as inextricable from the Earth provides a welcome foil to increasing attempts to escape it, like recent responses to the realities of climate change that embrace virtual or cloud-based worlds.⁵

Freije’s recent sculptures also traffic in a kind of hyper-materiality, albeit one more rooted in design and industrial materials. Composed of cage-like metal bands, the figures either resemble or are interspersed with light fixtures. They kneel and stand in various positions of awe and cowardice as though mimicking the postures painted in Renaissance depictions of Judgement Day. But instead of ascending to heaven among angels, or descending into hell among devils, Freije’s subjects are cyborgs, not the souls of mortals. In her merging of the technological with the human form, Freije asks us to imagine a future in which the human and the commodity can no longer be effectively distinguished. Like Freije, Cameron-Weir harnesses neomedievalism to further an investigation of the commodity form, a Marxist term that describes the way in which so many features of cultural life have taken on the form and function of objects that are salable or exchangeable. In Joy in Repetition (all works 2022), two similar industrial fireproof doors lean against the gallery’s back wall, providing weighted support to two identical hanging bronze reliefs of a fallen Christ being tended to by his acolytes. The sizes of the massive doors and smaller reliefs are proportional to each other and, like most objects in the exhibition, cold and greyish in tone. The phrase Joy in Repetition reads like ad copy or a hokey slogan touted by a furniture store—an ironically upbeat title for a work that summons both Jesus’ sacrifices for humanity and the power and dangers of industry. The work flattens two disparate temporal lines through their formal similarities, creating an aesthetic harmony that enables Cameron-Weir’s wry subversion of contemporary marketing clichés. Juxtapositions of medieval Catholicism and contemporary consumer culture also structure Cameron-Weir’s Florid Piggy Memories brought to you on the wing of the Common Ground Dove/ Dressing for Lectern. In this work, a dirt-smeared

Kira Freije, the sudden sleep (2022). Stainless steel, cast aluminum, and copper, 61 × 40 × 40 inches. © Kira Freije. Image courtesy of the artist and The Approach, London.

Photo: Michael Brzezinski.

Kira Freije, the sudden sleep (2022). Stainless steel, cast aluminum, and copper, 61 × 40 × 40 inches. © Kira Freije. Image courtesy of the artist and The Approach, London.

Photo: Michael Brzezinski.

display case that might have once contained jewelry or watches is instead filled with slides depicting medieval religious sites and modern violence alike. The images include a depiction of the Virgin and Child from a thirteenthcentury missal, the Salisbury Cathedral, the Gurk Cathedral, a series of concrete blast walls, and the stern deck of the battleship USS Nevada, which was subject to atomic bomb tests in 1946.⁶ Each photograph, adorned with an ornate pewter frame, is joined to its neighboring photograph with small, circular electrical components recalling jewelry clasps. First, CameronWeir materially and conceptually links medieval religiosity and its orientation towards Judgement Day with the twentieth-century development of world-ending bombs. Then, she turns the fear, grandeur, and gravitas of God and the A-bomb into mere ornaments, as though the end-ofworld anxiety of today was already expressed through, or implicated in, the commodity form. Cameron-Weir’s assemblages respond to, rather than erase, the fraught prehistories of the objects that comprise them. Dressing for Windows/ Dressing for Altitude/ Dressing for Pleasure positions a damaged fighter jet seat opposite a sculpture of the Virgin Mary kneeling in prayer on a furniture dolly. Their colors and curved forms are uncannily similar, and they both function as counterweights to a leather jacket affixed with meat hooks to a verticallysuspended conveyor belt. Here, the violence of Christ’s crucifixion implied in Mary’s piety is paralleled with the violence of a fighter jet that has presumably been struck down and plundered. The meat hooks and leather suggest further violence, still, pointing to the brutal slaughter and processing of animals. Dressing for Windows evokes an overdetermined narrative of violence that lingers throughout the show yet is impossible to fully comprehend—much like Eco’s account of the endurance of apocalyptic anxieties.

Many expressions of the neomedieval respond to present desires to remystify our relationship to

the Earth, and ourselves. They offer us a chance to escape—or at the very least, aestheticize—the powerlessness we feel in an increasingly technologized and globalized world. But rather than provide avenues away from our world, Cameron-Weir and her contemporaries route us back to it through the deep past, as if to say the medieval is once again contemporary.

Isabella Miller lives and works in Los Angeles.

1. Umberto Eco, Faith in Fakes: Travels in Hyperreality, new ed. (London: Vintage, 1995), 72. (Original work published 1973).

2. Eco, 104.

3. Commedia dell’arte was an early form of improvised theater that emerged in the 1600s, not in the Middle Ages. However, neomedievalism is an aesthetic mode that collapses distinctions between the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. The flattening of the two eras abounds in popular media like Game of Thrones, or even at the Renaissance Faire, a primary site of neomedievalism.

4. Western Catholicism characterizes Mary Magdalene as a penitent sinner partially because biblical exegeses from the Early Middle Ages conflate her with St. Mary of Egypt. See: Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1994).

5. See: the island country of Tuvalu’s plans to upload the country to the metaverse. Simon Kofe, “Rising sea levels force Tuvalu to move to the Metaverse: COP27 speech,” YouTube, November 15, 2022, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=lXpeO5BgAOM.

6. Alex Fox, “Researchers Locate Wreck of Battleship That Survived Pearl Harbor and Nuclear Bomb Tests.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, May 13, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ wreck-battleship-survived-pearl-harbor-and-nuclearbomb-tests-found-180974860/.

society,

At the recent Art Basel Miami, artist rafa esparza invited members of his Los Angeles community to mount and ride his body, having transmuted himself into a lowrider. For the performance, titled Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser (2022), gold-plated casts of esparza’s forearms and feet, a beach cruiser bicycle frame, and a retrofitted 25-cent mechanical children’s ride were welded together. The artist inserted himself into the makeshift bike frame, back arched, belly down, arms extended, chin propped up. Four sets of glistening chrome feet fanned out behind him, webbed together by neon green painted aluminum. Baroque-style twisted handlebars rose out of esparza’s head like antlers ready to be grasped. esparza’s friend, artist Gabriela Ruiz, inserted a coin to start the bike. Wearing a pair of headphones, riders took turns privately listening to esparza’s voice as the bike bounced the both of them. Collaborative to its core, Terra Cruiser was realized with help from esparza’s artist community, including Ruiz, Victor Barragán, Karla Ekatherine Canseco, Fabian Guerrero, Mario Ayala, and Guadalupe Rosales. Drawing from lowrider and cruising culture as well as Indigenous motifs, esparza’s lowrider cyborg imagines shapeshifting as a tool for transgressively animating the nonhuman. Terra Cruiser embodies what postcolonial feminist theorist Chéla Sandoval refers to as a “cyb[org] form of resistance,”¹ in which the embrace of hybrid creatures becomes an effective method of refusal under postmodern cultural conditions that

encourage conformity. Sandoval argues that “the colonized peoples of the Americas have already developed the cyborg skills required for survival under techno-human conditions as a requisite for survival under domination.”² In an inherently queer union of animal and machine, both primordial and bionic, esparza’s lowrider utilizes cyborg skills to deconstruct traditional notions of the lowrider, the nonhuman, and the human.

Past works have seen esparza chipping his ensconced body out of a concrete pillar outside the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in L.A’s Chinatown (Bust. a meditation on freedom., 2015) and having his full body painted for 12 hours for the first iteration of the lowrider work (Corpo Ranfla, 2018). esparza is intimately familiar with physical and emotional shapeshifting and duress, adapting the embodied stakes of each of his performances to its site. This ability to adapt and shapeshift—qualities necessary for resistance—is evident in esparza’s many transformations of his body. Upon his return from Miami, I sat down with esparza at his Boyle Heights studio to discuss ideas of animacy, the nonhuman, and queer kin. And, as it turns out, the cyborgian has been a part of esparza’s practice all along.

stephanie mei huang: You have referred to your work as “lowrider armor”³ and described the joys of honing in your own self-presentation. Can you speak to this idea of arming yourself through adorning and how that might function in your daily life?

rafa esparza: Sure. That’s something that I think a lot about in terms of the relationships that queer people of color have with fashion, clothes, makeup, and accessories. I think all of these things are tools that allow us to express ourselves in a heteronormative world that enforces this gender binary. [When] I was talking about body armor,

stephanie mei huang Image courtesy of Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles / Mexico City.

Image courtesy of Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles / Mexico City.

I was thinking about my relationship to fashion—the ways that I’ve fashioned myself, how and by whom I was taught how to carry my masculinity, and the ways that I choose to intervene in that. To me, [the way that] our communities have customized and built these cars feels so inherently queer…in terms of the choice of these very vibrant color combos that are dusted with shimmering metal flakes —oftentimes they have a rainbow-like reflection. Again, all of these things feel like the ways that accessories are used [in queer expression].

And armor, I think it’s something that also emboldens you and empowers you to just step out into the world— those decisions that we make every day that are literally how we choose to show ourselves to the world. It made so much sense for [the Terra Cruiser] to have that function—an armor that’s expressing a style and an aesthetic, but also very pragmatically, I’m turning myself into a car. So, how [do I] embody this machine and these aesthetics in a way that makes sense to me and my body and how I know it in different spaces and [especially] public spaces?

smh: In order to become the cyborg lowrider, there is a sense of morphing into another entity entirely. The ride requires your presence to animate it, yet there’s this balance between the fact that you are actually still when you are in it, but you’re still moving. I’m drawn to this tension between the animated and the still, human and nonhuman. In their book Animacies, Mel Y. Chen suggests that “queering is immanent to animate transgressions, violating proper intimacies (including between humans and nonhuman things).”⁴ How do you approach the nonhuman?

re: The more that I thought about how to configure my body in relationship to a form, I started to pay attention to what parts of a car (or a bike, in this case) my body [could] conform to. [I was] trying to push beyond things that felt very obvious in the first

go-around. Like, what part of a human body becomes the windshield of a car? What part of the body becomes the tires or the hood or the trunk? It was this collaging of my body with silhouettes of different cars—I remember cutting up pictures of my body and rearranging them.

I was thinking about this relationship between human and machine and of course, a cyborg or a cyborgian narrative. [In] most, if not all, of the contemporary narratives that exist about cyborgs or dystopic features, there’s a sort of dependency on technology and machines that are used to enhance the human body. I started looking into a history of anthropomorphic images, where you see humans becoming animals and plants and inanimate organic objects… It informed how I wanted to move forward with this project.

I wanted to make [the sculpture] more about what I think is an Indigenous sensibility towards nature and animals. [I] wanted to think about this machine [and] the progenitors of these cars, [who] happen to be people that are in the U.S. that come from a diaspora from colonized countries. I was just attending to these “coincidences” of the images—a lot of [what] these cars are embellished with happen to be these very proud [images of] Indigenous histories, these kind of Aztec figures. [What] if I take on this mission or this process of becoming a machine —what is at stake? Why do that? That question is what informs how the piece ends up existing. I want it to be more about learning about this machine, and literally, that’s [what] my performance practice is for me. It’s an embodied way of building a relationship to space, to people, to objects.

smh: It’s interesting to think about the cyborg still needing other people… the cyborg as a relational being.

re: I feel like gathering my queer family around this performance made it so that I could kind of just allow myself

Top: Photo: Star Montana.

Bottom: Image courtesy of Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles / Mexico City.

Top: Photo: Star Montana.

Bottom: Image courtesy of Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles / Mexico City.

rafa esparza, bust: indestructible columns Act I (performance view) (2019). Image courtesy of the artist, Performance Space New York, and Ballroom Marfa.

Photo: Natalia Mantini.

rafa esparza, bust: indestructible columns Act I (performance view) (2019). Image courtesy of the artist, Performance Space New York, and Ballroom Marfa.

Photo: Natalia Mantini.

to be part of this, like, machine that’s gonna give people rides. We built the frame as such that it could, when I’m not in it, still gesture toward a body. But when I’m in it, it actually needs someone to activate the machine. I have no way of powering it. So, having Karla there, having Gabriela there, just having my whole family there, and having them be the ones that are guiding people aboard this machine, brought intimacy into the work. I don’t know what that would’ve looked like otherwise.

smh: There’s also this both literal and metaphorical process of bottoming with the level of trust that is required in this piece. How did it feel to have members of your community ride you?

re: That felt almost like a given. Back when I was doing my undergrad work, there were pieces that were attempting to think about the language that we use to describe a type of engagement. “Fucking with my ancestors” —I remember that that idea, that phrase, was so present—never verbally or written or even explicitly expressed through a single artwork. But [it’s a] playful, sexual, and colloquial term that a lot of working-class POC use. When you fuck with someone, it has so many meanings, right? You’re either fooling around with someone, you’re being playful with someone. You engage with someone in a respectful way. Like, “I don’t fuck with this person,” or “yes, I totally fuck with that, that’s really cool.” You know, there are different ways of saying this word that I loved to think about when I was thinking of how to engage with nonliving people —just thinking of a spirit, an essence, an energy that inspires thinking, that inspires images. How [can I] engage with those beings, those entities, those histories, those memories in a way that felt real to me and not so academic? And, [not] just, I guess, boring. And so here, obviously growing with my practice and with these ideas and then growing within a queer community, I feel like this work embodies that same phrase. Really fucking

with my community, fucking with my friends, fucking with the art world, you know? Fucking with them literally. Riding and being ridden has also very vast and similar connotations, right? Riding someone, or being ridden: Both of those things could be seen as either topping or bottoming. I wanted that to be part of this work. I wanted to intervene in the history of this male-dominated space of building cars, you know? I’ve had a very conflicting relationship to those spaces, in terms of my being queer.

smh: It can be a very macho space.

re: Yeah. Queer [people’s presence] felt very lacking [in car culture]. …We didn’t see ourselves explicitly [or safely] represented in these spaces. I wanted [the work] to be both [an embrace of] this lowrider thing and also [to] unsettle it at the same time. I have family members that build cars. I have family members that have cars that are part of lowrider car clubs. I wanted to bring into question the ways in which these cars are so celebrated and lauded in public spaces. And then how it might be the complete opposite for queer people in public spaces. And so, joining these two different bodies, an auto body and a queer body, within this lowrider ride that could actually be ridden by another person. What [could that] evoke?

Having my friends, having my community be the people that rode me was a way of supporting or participating in this conversation. There was also something about, for me, questioning the kind of public space that we were in—an art fair, that [is] very inherently already exclusive for my community by virtue of it being in Miami, but also [the fact that it is a] ticketed event that is very inaccessible for a lot of people in my community. So the invitation to ride this work was another very important aspect of the performance.

smh: I appreciate that about your work and the spaces I’ve seen your work in—there is this sense of inviting. It was really formative for me when

I saw your show at Ballroom Marfa in 2018, to see the people that you invited to be a part of it. I think that Marfa is really different now, but it was just the first time I felt like a space in Marfa felt restored to its people—the majority of the people who live there. Whenever you have a solo opportunity, you are inviting other people in your community in.

re: There are words and functions of art that are turned into catchphrases that become very prevalent in terms of how a broader kind of art public talks about art. I am constantly trying [to] resist that legibility, even just in ways that, like, the word “community” has been so co-opted and overused. There is something to me that is still really important about unsettling, like, notions of authorship and ownership. Museums and well-established art institutions have been brought to task in terms of how they think about inclusivity and diversity. At this point, as much as I know about museums, that is something that I’m probably not gonna see in my lifetime. It feels like it’s very slow. There are so many things that have to change.

The best thing that I could do is have my community participate in resources that I have and have access to spaces that I have access to. Also, [participating] in spaces that are forming themselves and [helping to] build spaces that are informed by an ethos and a culture that is not present in these traditional art spaces.…[When you participate in community, there is an ease] of being able to contextualize what you’re doing, literally build a discursive space [where] you kind of see yourself active in the world. All of those are things that could happen when you work together with people.

stephanie mei huang is an L.A.-based interdisciplinary artist. They use a diverse range of media and strategies, including film/video, writing, sculpture, and painting. They were a participant in the Whitney Independent Study program (2022) and received their MFA from the California Institute of the Arts (2020).

rafa esparza (b. 1981, Los Angeles) is a multidisciplinary L.A.-based artist whose work reveals his interests in history, personal narratives, kinship, and his own relationship to colonization and the disrupted genealogies that it produces. esparza’s recent projects are grounded in laboring with land and adobe-making, a skill learned from his father, Ramón Esparza. Recent solo exhibitions have been held at Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles (2021); MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA (2019); ArtPace, San Antonio, TX (2018); and Ballroom Marfa, TX (2017).

1. Chéla Sandoval, “Re-Entering Cyberspace: Sciences of Resistance,” Dispositio 19, no. 46 (1994): 77, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41491506.

2. Sandoval, 76.

3. rafa esparza, “How rafa esparza transformed himself into a lowrider cyborg for Art Basel Miami,” Los Angeles Times, November 29, 2022, https://www.latimes.com/ lifestyle/image/story/2022-11-29/rafa-esparzabecomes-a-lowrider-cyborg-for-art-basel-miami.

4. Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Duke University Press, 2012), 11, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11vc866.

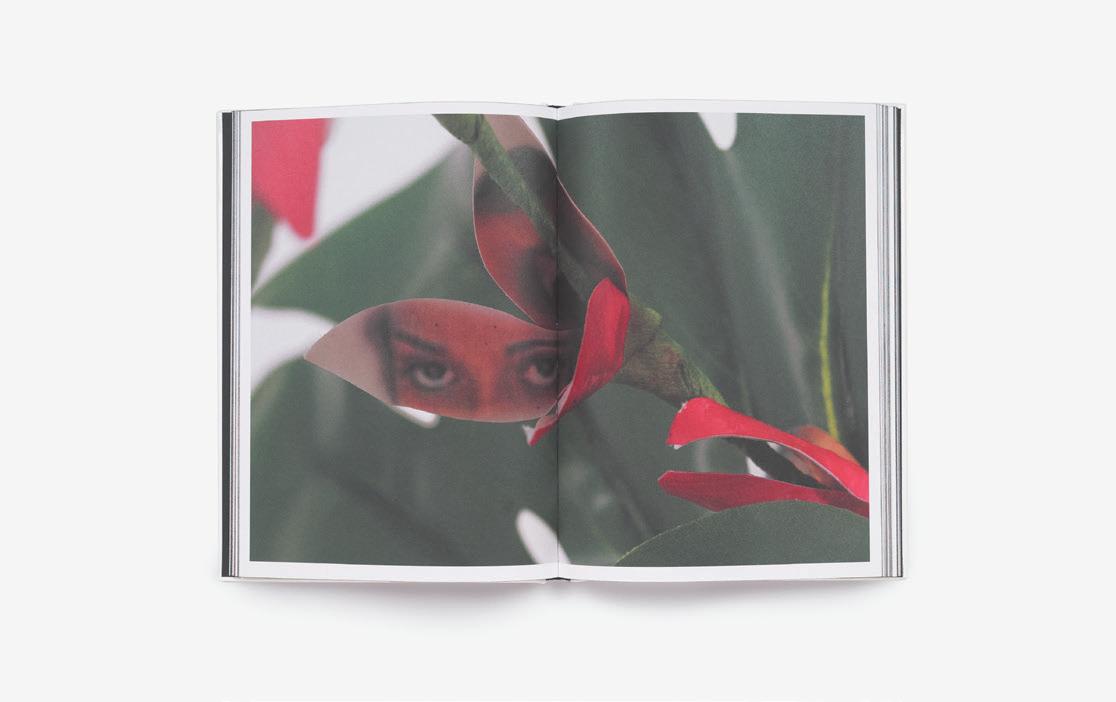

For the second iteration of “L.A. Harvest,” we turn to the idea of the ecosystem. A thriving ecosystem hinges on its internal harmony; interdependent organisms must collaborate in and with their environment, whatever it offers. Though sun-drenched and fertile, the steep hillsides of Los Angeles don’t always make a welcoming home. Acreage is at a premium, as are access to water and the blissful shade of oldgrowth trees. The intense uncertainty and isolation of the past three years have heightened existing threats to a stable and healthy life in this city—both horticultural and otherwise. The artists featured here represent those whose métiers and friendships combine to foster growth despite harsh odds.

Evan Walsh and Alika Cooper collaborate on city-wide group chats and plant sales, conceived in the depths of pandemicinduced isolation. Esteban Schimpf’s burgeoning indoor garden finds surprising harmony with the help of the inspired eye of designer Selina Che. Members of the artist

collective Crenshaw Dairy Mart tinker with plants in the abolitionist pod, a civic initiative to foster community well-being and reduce food insecurity through connections forged by art and gardening.

In a megalopolis that both sprawls and crams stacks of homes together, most can’t help but borrow from the scenery around them. These artists’ relationships with their plants and fellow gardeners are an argument for meaningful systems of support that allow manifold life to thrive in an often-inhospitable setting.

Evan Walsh’s and Alika Cooper’s generative partnership was forged amidst the pandemic in a plant-focused group chat now more than 30 gardeners strong. Their conversations grew into L.A. Plant Sale, a seasonal pop-up event featuring plants, art, food, and crafts hosted with the help of Plant Intelligence Agency, Myco Myco, and Fay Ray Clay. Seven years in the making, Walsh’s collection of potted desert plant specimens sit in rows on long tables in the side yard of his shared Highland Park home. A UCLA-certified horticulturist, Cooper focuses on specialty maintenance and works mostly in other people’s gardens. In Los Angeles, this often means embracing the concept of “borrowed scenery”—the incorporation of views beyond the confines of one’s garden. Though they engage in gardening in different ways, both artists emphasize collectivity as integral to their practice.

Artist Esteban Schimpf is a committed maximalist: a collector, arranger, and adorner. The delicate ecosystem that Schimpf has called home for nearly 15 years is replete with a careful curation of flora, found rocks and fossils, dried fruit, and an extensive sound system and music collection. When his outdoor garden lies dormant through the winter months, indoors his home teems with thriving tropical foliage, prickly cacti, and, most recently, ikebana floral arrangements featuring such nontraditional materials as iPhone cords. The painter-turned-photographer cites the tutelage of his friend, designer Selina Che, for inspiring this new practice of attending to the natural balance among disparate objects.

For Crenshaw Dairy Mart (CDM) co-founder and visual artist noé olivas, there is no separation between his art practice and the operations of CDM. In 2021 and ’22, the collective developed the abolitionist pod, an autonomous garden collaboratively cultivated in a geodesic dome in Hilda L. Solis Care First Village, a transitional housing facility in L.A.’s historic Chinatown. Throughout his work day, olivas moves between the pod and his adjacent studio space, tending to the ecosystem with CDM Program Director Vic Quintanar and member Taylor Lindsey, who also operates a plant shop and educational platform called The Plant Plug in her community of South Central L.A. Like all of CDM’s programming, collective participation is integral to the health of the pod’s ecosystem, ensuring that constant and individual attention falls on all its members—everyone watering, weeding, and turning the compost.

September 24–

December 16, 2022

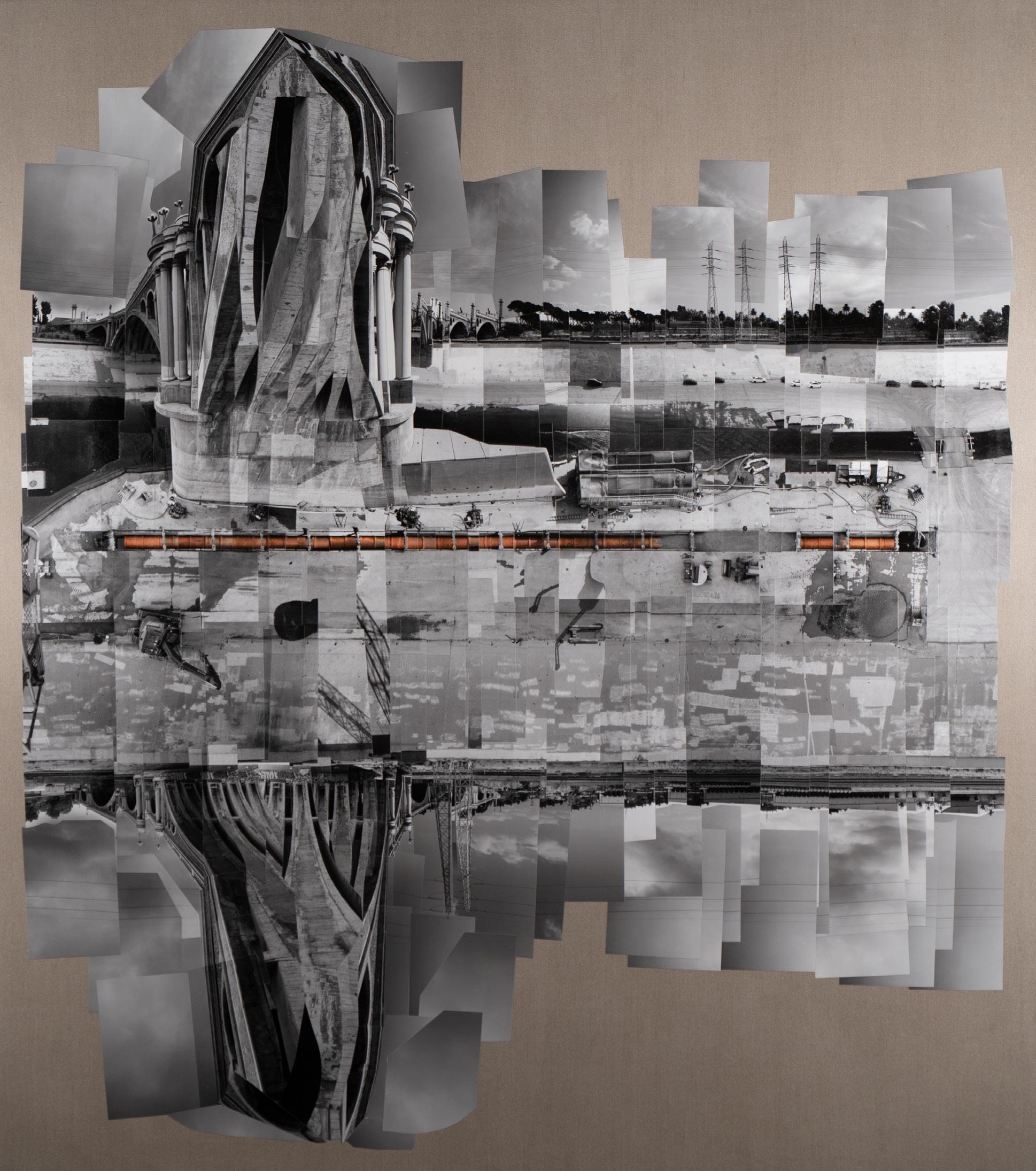

Metabolic Studio trades not in institutional critique, but in what we might term institutional speculation: What would it mean to build an organization that oversees public infrastructures with a different set of aesthetic, economic, and ideological reference points than we’re used to? The loose-knit group of artists, engineers, and designers organized around artist-philanthropist Lauren Bon has accomplished several feats of scale over the last two decades, notably transforming “the Cornfield” land parcel (now Los Angeles State Historic Park) into an actual cornfield (Not A Cornfield, 2005–6) and surveying the landscape of California’s Owens Valley with a giant pinhole camera made from a shipping container (2010–ongoing). The group’s recent show at Pitzer College focused on its largest project to date, Bending the River (2012–ongoing)—a years-long effort to dig into the concrete of the Los Angeles River channel and reroute oceanbound water for use in public parks. Given the ambitious scope of these works, some uncertainty lingers about what the Metabolic Studio actually is: Is it a utopian think tank? A private corporation? A temporary autonomous zone? The exhibition, however,

provided an impressive illustration of what the group does, modeling radical socialecological infrastructures and drawing on the language of art to communicate its aims.

While Metabolic Studio’s work is future-oriented, it has a retro pedigree, calling back to artists such as Agnes Denes, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, whose 1970s and ’80s interventions in urban space and infrastructure mark a transition from land art to the more capacious and ongoing genre of eco-art. At the Pitzer College Art Galleries, Bon and her collaborators foregrounded the imagination and the frustration involved in intervening in L.A.’s notoriously bureaucratic water politics. Near the front of the gallery stood An Expanding Block of Weighty Permits (2022), which is exactly that—a metal table covered in stacks of documents that archive, in legalese, the tangled process of securing a private water right to access the concrete channel (a process that involved more than 60 permits). If this work reminds viewers of the forbidding aesthetic of urban planning, other pieces communicate a sense of optimism: New Public Infrastructures (2022) is a 500-photo collage depicting the short span of the L.A. River that Metabolic Studio dug into to lay clay pipes for redirecting water. In the photos, the eye-catching, terracotta-colored pipes contrast with the industrial setting of the black-and-white concrete river, suggesting a path forward.

Between the Roots and Microbes; Leachate/ Filtration/Bioassay (2022) had the charm of an ambitious science fair experiment, with beakers of distilled water dripping into clay pots filled with lead-contaminated soil and various treatments, including biochar, mulch, plant ferment, and compost tea. The contraption is meant to determine which soil treatments can help decontaminate river water and encourages an expanded understanding of collaboration across species. The most impressive piece in the show was Living Room, an earthen pile of burnt logs, mulch, mycelium plugs, oak, and compost, irrigated with rainwater through a clay pipe. An expressionistic wash of the reddish clay covered the surrounding walls, while pinecones and rocks scattered on the mound contributed to the slightly stagey elegance of this earthy readymade. The piece is a conceptually layered neo-earthwork, an environmentalist echo of Hans Haacke’s classic soil and grass assemblage, Grass Grows (1967–9).

While most of the works in the exhibition comprised the larger Bending the River project, others referenced the group’s previous efforts: a photograph of Not A Cornfield (Ninety Miles of Irrigation Stripping, 2005) contributed a sense of Metabolic Studio’s trajectory, while Sound Map of Payahuunadü (2014–15) highlighted the group’s multisensory approach to mapping ecosystems. The piece comprises an aerial image of Owens Lake in the Central Valley—a region referred

Nick Earharta time to tear and a time to mend (installation view) (2022). Image

courtesy of the artists, SUPERCOLLIDER, and Wönzimer.

Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

courtesy of the artists, SUPERCOLLIDER, and Wönzimer.

Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.