4 minute read

The Persistence of Vision

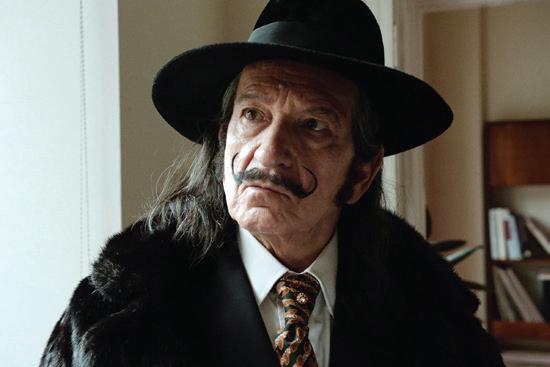

Dalíland begins with Salvador Dalí’s appearance on What’s My Line?, the classic game show where blindfolded contestants try to guess the identity of the mystery guest. “Are you a performer? Do you have something to do with the arts?” e contestants are ba ed because Dalí answers “yes” to everything. What nally gives him away is a question about his famous waxed mustache.

Dalí wasn’t lying. He was an artist, one of the greatest of the 20th century — and he was also a performer. e character he played for most of his life was Salvador Dalí, the crazy artist who is also a super-genius. “Geniuses are not allowed to die,” he said near the end of his life. “ e progress of the human race depends on us!”

Where the act ends and the man begins? Nobody really knows. Dalí really was a super-genius artist, the most famous of the Surrealists who terrorized the buttoned-up art world of the 1920s and 1930s. He was also his own best hype man. Ben Kingsley plays Salvador Dalí with more perfection than a ection. Kingsley rst came to prominence playing Gandhi in Richard Attenborough’s classic biopic, so he’s got experience with historical personages. Watching Kingsley apply his world-class chops to mimicking one of history’s great lunatics is, as you might expect, the fun part of Dalíland e Surrealists learned the art of the high-pro le stunt from the Dadaists. Dalí perfected it. At one point in Dalíland, he asks his assistant James Linton

(Christopher Briney) to bring him live ants and a full suit of armor that must be Spanish in origin. “Is it for a painting?” James asks.

“No, it’s for a party.”

Dalí’s wife and muse was Gala (Barbara Sukowa), the quintessential muse and “art wife,” the reasonably sane member of the relationship who keeps the books and interfaces with the “real” world. To say they had a strange relationship is a massive understatement. Gala appeared in several of Dalí’s most famous paintings, o en in the guise of the Virgin Mary. According to Dalí hanger-on Ginesta (Suki Waterhouse), they rarely, if ever, had sex — at least with each other. Gala had a ery temper, and a er one particularly intense tirade, Dalí turns to James and declares, “Isn’t she magni cent?” ere’s a lot for a lmmaker like American Psycho’s Mary Harron to work with — the story of some of the greatest visual masterpieces of the last century, the legendary eccentric who created them, and the weirdly functional, dysfunctional relationship that sustained him. Which is why it’s so puzzling that Dalíland feels like such a damp squib. e problem (one of them, anyway) is the point of view. Dalíland is not Dalí’s story, but James’, who we meet as a gallery owner in 1985, when Dalí was denying he was dying. en James ashes back to the early 1970s, when he was Dalí’s assistant for a few very eventful months. He rst meets the Dalís in New York, where the painter is holed up in a luxury hotel, creating a new batch of paintings for an upcom- ing opening. e Dalís live in a constant state of cocktail party, with artists, models, and assorted rich people hungry for clout, drinking champagne and snorting coke on Dalí’s dime. e lm works best when Harron gives in to the chaos: Watching Ben Kingsley trying to disco dance as 70-year-old Dalí is a particular highlight. e Dalís only operated on a cash basis, and James becomes their bagman — which means he sees both the people who are stealing from the artist, and the extreme, o en fraudulent methods Gala uses to keep the money owing. It would be nice if Briney could have summoned some kind of recognizable emotional reaction to that or anything else. Briney was apparently a last-minute replacement for Ezra Miller, who now appears as Young Dalí in ashbacks. While the guy who will appear as e Flash in a few weeks is apparently a malevolent weirdo in real life, at least he can kinda act. Briney drags down everyone around him, killing any momentum the lm builds up from Kingsley and Sukowa’s terrifying love story. e biggest problem with Dalíland is that you never get to see the artist’s paintings, only his eccentricities. Other people tell you how brilliant he is. Even though he was past his prime when James meets him, Dalí was the real deal. But unless you’re familiar with his work, and his biography, you won’t nd that out from Dalíland

Dalíland is playing at Malco Studio on the Square through June 15th and is available on VOD.

Our critic picks the best films in theaters. The Flash DC enters the multiverse with their speediest character. Star Ezra Miller, whose off-screen insanity and ensuing legal entanglements are bigger news than the film, plays multiple versions of Barry Allen, who uses his super-speed to travel back in time in an attempt to prevent his mother’s death. Is it a bad sign that Miller is being upstaged in his own solo movie by the return of Michael Keaton as Batman?

Elemental

Pixar storms back into theaters with a parable about earth, wind, fire, and water. Ember (Leah Lewis) is a no-nonsense fire elemental who falls in love with Wade (Mamoudou Athie), a “gowith-the-flow” water elemental. Can the two opposites make it work? Are little steam babies on the horizon? The Good Dinosaur’s Peter Sohn directs, and listen for a voice cameo from Adult Swim’s calmest Yooper Joe Pera.

The Blackening

If you’ve watched a lot of horror movies, you know that the Black guy usually dies first. But, director Tim Story asks, what if it’s ALL Black people trapped in a cabin in the woods?

Checkmate, knife-wielding maniac! Not so fast, says the killer, who attempts to rank his prey by degrees of Blackness, so he’ll know where to start. The Prisoner’s Dilemma meets Get Out in this horror parody.

THE LAST WORD

By Andrew Moss