18 minute read

Laurel Picklum

Written by Chris Jalufka Photography by Arabela Espinoza

laurelpicklum.com Facebook laurelpicklum Instagram laurelpicklum When you see the work of San Jose–based artist Laurel Picklum, there is no sense that she was meant to be anything other than a painter of the natural world. Her watercolors, murals, and oil paintings display clarity of vision and meaning. The daughter of scientists, Picklum was raised in a home that inspired exploration. “My parents have always encouraged curiosity and exploration, and I am grateful for that. We would go camping and hiking a lot when I was a kid, and I always brought home dead bugs, bones, or cool rocks I found.”

Advertisement

Picklum graduated in 2013 with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from San Jose State University (SJSU), followed by completing the Certificate in Natural Science Illustration program at the University of Washington in Seattle in 2016. Her path to her current role as a wildlife artist was not quite as direct as it may appear. Entering SJSU as a graphic design major, the allure of painting and printmaking took over. “My path as an artist has really been a manifestation of my indecisiveness. First, I wanted to do design, then I wanted to do gallery work, then I definitely did not want to do gallery work, then I wanted to do purely academic science illustration, then I didn’t.”

Picklum’s take on nature aims for scientific accuracy, following the inherent grace and balance of her subjects. Amongst her many works is a watercolor of Cornus canadensis, better known as creeping dogwood. The oval leaves are deeply veined and a healthy green, with the slightest bend in their sturdy skin. At the center sits the white blossom, lifted above the core. The leaves surrounding the blossom mimic the much larger leaves below—a small flower cupped within the shape of the plump

Tile page: Mural for Brik Clik, 6’x6’ Opposite: “S. 16th & E. William” Oil on canvas 10”x20”

Mural for the Guadalupe River Park Conservancy, 15’x85’

–Laurel Picklum

leaves it crowns. Like a photograph, Picklum’s painting perfectly captures the perennial, yet she takes it further, highlighting the natural beauty of this everyday plant and imbuing it with crisp afternoon light. In that light she brings the plant to life. “I try to make my illustrations and paintings as scientifically accurate as possible. I do, of course, try to make the compositions aesthetically pleasing, but more often than not, nature does the work for me.” She has been hired by the world of academia for her scientific illustrations, but the experience was not a pleasant one, as Picklum puts it. “I’ve stressed myself out worrying that [an illustration] wasn’t scientifically accurate enough, and I ended up feeling like the pay wasn’t worth the anxiety.”

She has since turned her focus on commission work, and her latest project is a series of paintings exploring how native species exist in urban environments. “I see hawks in San Jose, and I wonder where they roost and what they’re hunting for, flying over downtown. I’m always thinking about how animals have managed to survive in the Bay Area despite decreasing natural resources, polluted waterways, and fragmented habitats.” One project that highlights Picklum’s desire to explore native wildlife is her Guadalupe River Conservancy mural. Across a stretch of wall beneath the Coleman Avenue bridge along the Guadalupe River, Picklum and her team crafted a mural depicting the plants, insects, and birds that call the river home. The piece details the impact that mindless litter and the careless dumping of materials has on the valuable ecosystem of the river.

The mural was a project brought to Picklum by San Jose arts nonprofit Local Color, an organization for which she has been an artist in residence going on two years. “Local Color has ended up being a positive, nurturing womb for my creativity. Being surrounded by other hard-working artists is so inspiring and encouraging. The women in charge (Erin Salazar, Haley Cardamon, and Carman Gaines) are constantly working to find paid opportunities for the artists, which has made such a huge difference in my career, and I know many of the other artists would say the same.” Picklum recently worked with Local Color on LoCo Recess, a program providing free creative workshops to kids who would not normally have access to art lessons. With each workshop featuring local professional artists sharing their knowledge with local youth, Picklum gave instruction in the use of watercolor while offering encouragement and guidance.

Being an artist in residence with Local Color gives Picklum a studio space to work in, free of the distraction of home life, something that she is grateful for in this time of global quarantine. “At the beginning of SIP (shelter-in-place), I was trying to work from home, and I went probably six weeks without finishing a single painting, which really created a downward spiral of selfdoubt and obstruction. Luckily, Local Color has re-opened for us to work. I feel very lucky to still be able to work at my studio. I would not have been able to be productive if I had to stay in my house.” C

MESNGR

Written by Taran Escobar-Ausman Photography by Daniel Garcia

In the world of graffiti, elements of typography give way to the movement of calligraphy, which are elaborated on within the lettering of a simple tag or the abstract styling that adorns large mural pieces. The fundamental rules of typography and calligraphy may be adhered to in graffiti, but they are also broken, creating a more intimate expression of experience and existence. Author Robert Bringhurst says, at the heart of typography is the “dance, on a tiny stage, of the living, speaking hand.” While Bringhurst was in no way referring to graffiti, he inadvertently summed up the ethos of graffiti with the phrase “speaking hand.” Tracy 168, pioneer of wildstyle graffiti, bridges this connection between typography and lettering in graffiti when he succinctly, yet enigmatically, states, “You don’t want to lose the basis of the letter, but you want to lose the letter.” The very fabric of graffiti is a dichotomy between established form, practice, and rebellion.

This is where we find Mesngr, who, as an adolescent, began spraying the names of punk bands behind an Alpha Beta grocery store in San Jose. He viewed the city as a living canvas: seeing art in cars, buildings, signs, and the people within the community. Like so many at that age, Mesngr’s rebellion consisted of the need to be seen, and he made art and graffiti his vehicles of choice. “When I discovered graffiti, I could say, ‘fuck you,’ or I could say, ‘Look at me—I exist!’”

A San Jose native, Mesngr is a self-taught illustrator, street artist, mentor, and teacher. The rebellious start to his journey blossomed into his work becoming part of the visual landscape of San Jose. Large mural works in Japantown, a high school mascot mural for the Yerba Buena Warriors, and his large bus and character piece in the Alameda Artworks parking lot are just a few works bearing the Mesgnr handle. In addition to seeing his many murals, characters, and tags, typical San Jose residents going about their day may not realize how many times they observe Mesngr’s work. The Ike’s Sandwiches logo or the Diamond Cleaning Services billboard are examples of Mesngr’s love of letters and design in a commercial setting. The quality of the crisp, clean lines apparent in all his work, something he has always strived for since watching his father use a fountain pen to pull perfect lines for his lettering and calligraphy, makes it hard to believe he pulls lines with spray paint. The range of Mesngr’s influences can be seen in his graffiti work, especially in his lettering where the Bay Area ‘funk’ style mixes with the wildstyle of New York and is highlighted by

or I could say, ‘Look at me—I exist!’”

–Mesngr

the playfulness of bubble-style lettering, seen most often on throw-ups (a style of quick graffiti lettering). In his pieces, he integrates the cartoon stylings of his early influences, Don Martin and R. Crumb, the freeform movement of Mode2, and the controlled pop art lines of Patrick Nagel. The result is his own vibrant style depicting the personalities that make up San Jose and creations from his own mind. Mesngr gravitates toward the female form to adorn his pieces, it being “simple [yet] beautiful and unique, expressing all my feelings [of] peace, love, darkness, pain, good and evil, mystery, sex, life, hope, and passion.” While at the heart of graffiti is an independent and personal intent to establish a presence among many, the concept of community plays a major role as all those personal voices, or “speaking hands” come together to paint a visual representation of a city’s soul. “Graffiti is an art form that is needed in our community, just like murals, because when you have a high-paid out-of-towner or even an established local artist painting a mural, it reminds us there’s a voice, a talent and passion in the people from these streets.”

Mesngr is very humble and would rather throw the spotlight on those that continually inspire him, like fellow artists Sean Griffin and John Dozier of the art collective TWC (Together We Create), which he is a member of. Even in the capacity of educator and mentor, he gathers more inspiration from the at-risk youth he teaches. “I hope and believe that art teaches them patience, the ability to see things through, and to stay creative. Those things apply to all parts of life and a young person’s future.” Mesgnr has surely shown he exists to help bring out the soul of San Jose and care for its future. C

Caryn OwenHouseofBoys

Caryn Owen raised a house of boys and taught marine biology for twelve years before becoming a full-time artist.

As a marine biologist turned full-time artist, Caryn Owen experiences the beach in several different ways. By the time you ask how, her eyes have already scanned the horizon for signs of life. As an artist, she has absorbed the deep blues of the ocean and the sighing coastline. These colors will eventually represent themselves upon a canvas, remixed in new lines and shapes. In essence, this is the inspiration of HouseofBoys.

Owen’s childhood in LA gave her a robust rotation of extracurriculars. From dance to theater arts to TV commercials, her artistic leanings were prevalent, but passion also carried her in academia. During a day camp field trip, a young Owen had the chance to snorkel in a coral reef tank and briskly fell in love with the ocean.

Years later, at Duke Marine Lab, she studied marine biology under famous dolphin and seal scientists. After working in several marine labs across the country, she settled in Santa Cruz as a marine biology professor. Through marriage and motherhood, this life would be hers for twelve-and-a-half years. Teaching at Foothill College allowed her the flexibility to be a professor and a mother, raising her family in a house by the ocean.

One day, she intuited the conclusion of this lovely, long chapter. “I’m done,” came the thought and the realization that her sons were old enough to care for themselves. As for her own soul, it was “bursting at the seams with creative energy.”

Owen had contemplated pursuing interior design, which she had loved even as a child. Friends in her adult life, admiring her ever-evolving home interior, had consulted her on their own homes; and sometimes, when she wanted a piece of abstract art she couldn’t afford, she would paint a copy of it herself.

But the idea of creating her own paintings was terrifying.

If it was time to turn a hobby into a career, should she pursue fashion, interior design, or painting? What, at this time in her life, reflected and captured everything she was drawn to?

Then, a friend decided to throw a house party. “I have a friend making purses and selling them. Why don’t you come and sell prints of your paintings?” her friend suggested. “See how it goes.”

That fall of 2015, Owen completed her last year of teaching. Using her retirement funds, she built a studio in the backyard. For a year, she rested. Then she dove in: She participated in Santa Cruz’s First Friday every month for a year

Written by Esther Young Photography by Liz Birnbaum

houseofboysart.com minted.com/store/houseofboysart Instagram houseofboysdesign

Coastline Swell

Abstract Geometric

–Caryn Owen

and a half, simply learning. “Santa Cruz is such an amazing art town,” she emphasizes. “They’re so welcoming to new artists.”

One day she entered a contest by Minted, a company that sells prints, stationary, and other giftable items featuring independent artists’ designs. The winning artist would not only have their art printed and sold, but be promoted by the platform.

“I have nothing to lose,” she thought going in, and HouseofBoys took the cake. Over the course of a year, her art was promoted nationally as she also worked independently to sell original pieces at West Elm’s maker’s market in Emeryville and open studios before the pandemic hit.

Before COVID-19, while her sons were away at school, Owen would use a typical school day to paint and create in her studio, take pictures of her art and manage her marketing. At 3pm and for the next four hours, she would return to “mom mode,” driving kids around and making dinner. In the evening, she would return to social media, Etsy, and promoting her art.

The pandemic cancelled her big shows and tours. But with shelter-in-place and the normalization of virtual meetings, Owen noticed an uptick in consumer demand for her prints as wallpapers. In March, one of her pieces also became a free Zoom background, distributed by Minted.

Owen’s backyard studio is her safe haven. In the summer of 2016, when her father passed from a sudden illness, that studio held her grief as she painted nonstop. It was her centering point, where she could “not think about anything but color.” Her father had been a gardener, and as she focused on colors, abstract landscapes and seascapes began to appear under her brush. “It was strange; it wasn’t intentional,” she remembers. “I hadn’t set out to change my art...but it really helped me.”

On Instagram, Owen followed a natural instinct to promote herself. “Perhaps that’s the 42-year-old in me not caring at all,” she jokes, but when she feels in her gut that a piece is right to share, she doesn’t hold back. Owen is usually working several canvases at any given time, and each piece needs to “marinate” before deemed finished. “Everything to me is about color,” she explains. “It’s color first, and then form.”

The hardest part of selling online is getting a good picture. “I’ve used my house to showcase my art...but my taste changes so quickly, I need a white background!” she laughs. Inspiration is raised and nurtured in her home. Oftentimes, the hues of pillows she’s using and shirts she’s wearing end up in her paintings.

For the artist who lives in color, her greatest pride is giving her all. “I’ve given this business everything, and I haven’t looked back.” C

COLORSTORY SAMMY

Written by Esther Young Photography by Rob Schultze

Etsy colorstorysammy Instagram colorstory_sammy SAMMY KOH’S LANDSCAPE paintings are an invitation. Though photorealistic in detail—each frond of a palm tree drawn with a tiny brush—they present as open-ended offerings more than a precise, predetermined point of view. Like the way Sammy views her life, moments of beauty in nature are fleeting. But they can be evoked, regifted, to facilitate peace and healing.

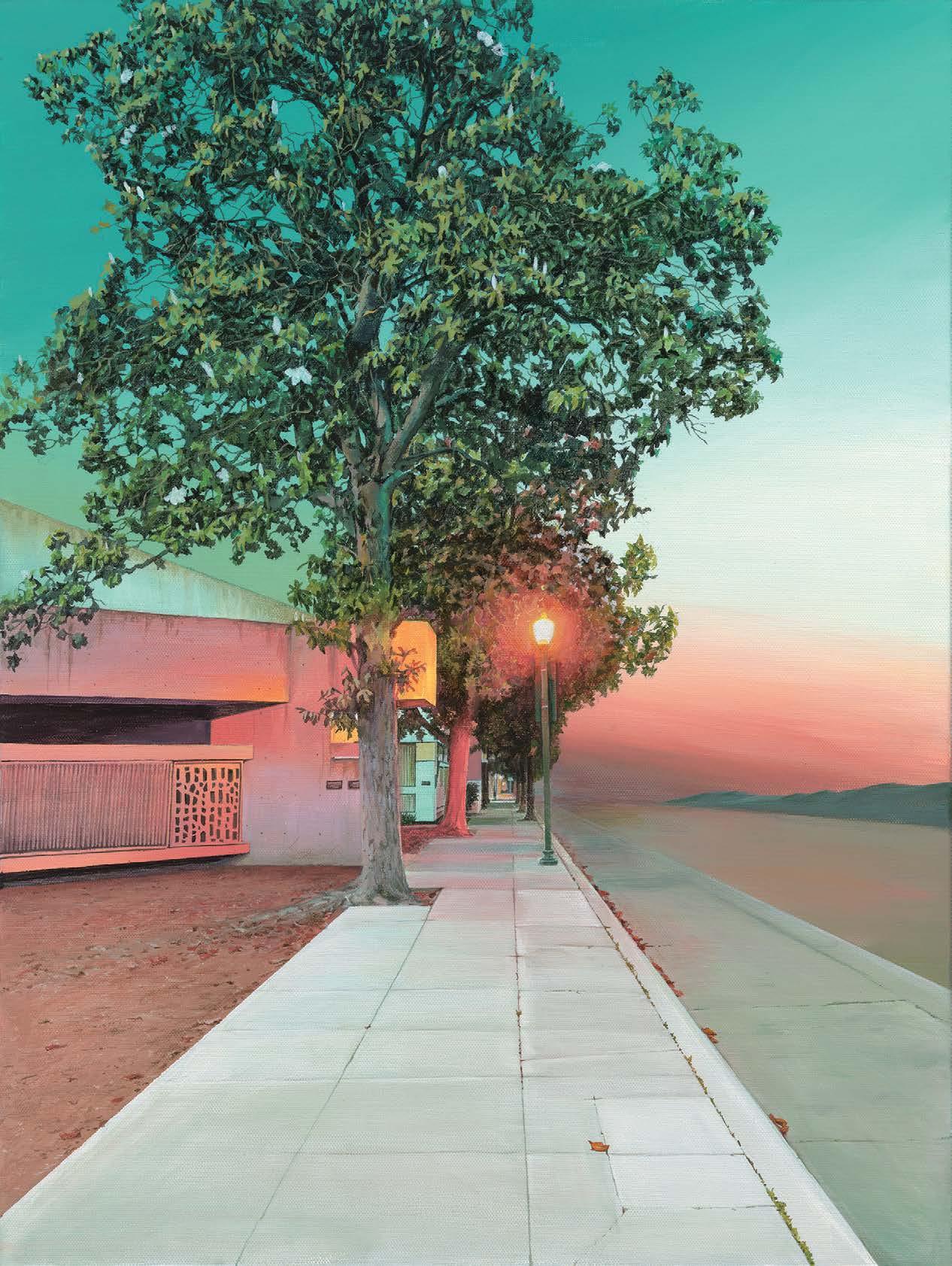

“I wish that people who see my paintings sense the peace and quiet I feel in painting.” She doesn’t draw in human figures so that viewers can “put themselves in the place they want to be...to have a moment to think about their own life.” While pointing to a landscape of California Avenue in Palo Alto, where a street lamp shines its brilliant sphere of luminescence into an overarching tree, she says, “They can stand under the lights. I want them to have time to think.”

Attending school for graphic design in Korea, Sammy did not anticipate becoming a painter. She always held an art dream of her own and worked as an illustrator before immigrating to the US with her family. Once they arrived, her focus was on her son and daughter, who were three and five years old at the time.

Eleven years have since passed, and Sammy has created a community around her in Palo Alto. Just a year ago, she began teaching art classes in her home, focusing on still life and portraiture. Many of her students are also immigrants, mothers of grown children rediscovering the joy of making art for themselves. As they draw and paint, they chat and listen to music. Their finished pieces, many of which feature their children, pets, and plants, can still be found on Sammy’s Instagram.

When she transitioned the art class to landscape (painting), the rush of positive feedback stoked her own appreciation for her artwork. In March, as the pandemic canceled her classes, she started to paint more landscapes. As she took more scenic drives and walked around her Palo Alto neighborhood, the ephemeral spirit of sunsets and sunrises stuck with her. “I never miss this moment on a trip,” she smiles. “They are beautiful, but disappear quickly.”

Sammy’s process centers around these precious moments. She prints her photos out, puts them on a wall, and gazes at each to recall the emotion they carried. Much of her time is spent editing images to create a magical effect—a lone bench at Capitola Beach might rise to new heights to overlook a sunrise; a garage door might carry an ocean; and windows, in many of Sammy’s paintings, reflect the warmth of her favorite natural phenomenon.

Within these pieces of art, suburban environments react with romance: street pavements glow in pinkish hues; mailboxes and fire hydrants pop from the sidewalk like ornaments; doorways are always open, revealing worlds of imag-

Sunset Beach

ination, the sweetness of hindsight. Yet any natural entity—be it tree, bush, or crawling ivy—is portrayed in painstaking hyperrealism. “It can take five hours to draw one tree,” Sammy explains. The contrast should be jarring, but the result is serene. Yet if the dreamlike elements in these otherwise photorealistic illustrations hint at the shivery, spell-cast atmosphere of the half-light before dawn, perhaps the viewer has caught a rare vibe from the creation process. Sammy’s painting occurs between 2 and 6am. In the quiet, as her family sleeps, she paints. Sometimes, at the break of dawn, she goes out to take pictures. But she returns home soon after, because the “kids and husband ask for food.” After breakfast, she naps before heading to her computer for Photoshop work. Evenings are for family time, walks before dinner, and a second nap before midnight, when she wakes up for more nocturnal art-making.

Sometimes, though, her children join in. On occasions when her daughter accompanies her on photo shoots, Sammy likes to use the photos taken by her daughter. “Whenever I remember the scene, it warms my heart because of her.” And those feelings, in turn, enhance the painting. Other photos are selected by her son. “He kindly explains to me why he picked them,” she shares proudly.

In addition to teaching others to paint, Sammy invests in the community that supported her journey as an immigrant woman. Simple Steps, a 510(c)3 organization founded in 2017 by a Korean immigrant, empowers immigrant mothers to stay in the workplace and further their careers against the odds of limited support networks, language, and cultural barriers. In June, Sammy led a workshop on Instagram marketing for her fellow Simple Steps artists. Sped-up process videos, she shares, are popular right now. Though editing these videos takes time, she aspires to continue posting them for her followers.

Finally living her own dream, she recognizes the different dreams of her children and cherishes their enthusiasm for hers. “I think about when I am an 80-year-old grandma,” she laughs. “I would be happy painting. So, this is my dream.” And if there was ever a proud moment in her life, “I think it’s now.” C