5 minute read

POWs celebrated

Exhibition commemorates 50th anniversary of the return of North Vietnam prisoners

By MARTINA SCHIMITSCHEK

Advertisement

Ahalf a century has passed since the last Vietnam prisoners of war returned to the U.S. through Operation Homecoming.

Altogether 591 men — 325 Air Force, 77 Army, 138 Navy, 26 Marines and 25 civilians — were released and returned home between Feb. 12 and March 29, 1973. Some were in prison for months; but for many, it was years.

When they touched down on home soil, a lot had changed in America for the men held an average of five years at the Hoa Lo Prison, better known as the Hanoi Hilton. The prison held its first American POW in 1964.

While the men were struggling to survive, often in solitary confinement, the country had undergone a cultural shift. During this time, the first man walked on the moon, Attorney General Robert Kennedy was assassinated, three days of peace and love at Woodstock rocked the music world and Thurgood Marshall became the first black Supreme Court justice.

Retired Navy Capt. John Ensch sees himself as one of the lucky ones. He was held prisoner for less than a year.

Ensch had flown 284 successful missions as a radar intercept officer when on Aug. 25, 1972, a surface-to-air missile took down the F-4 Phantom fighter plane piloted by Lt. Cmdr. Michael Doyle over North Vietnam. Both ejected from the plane, but only Ensch made it back home.

“I don’t think it took me very long after my return to feel re-assimilated. I was lucky that I was shot down in the last year of the war, so things in the U.S. hadn’t changed that much before I returned,” Ensch said via email.

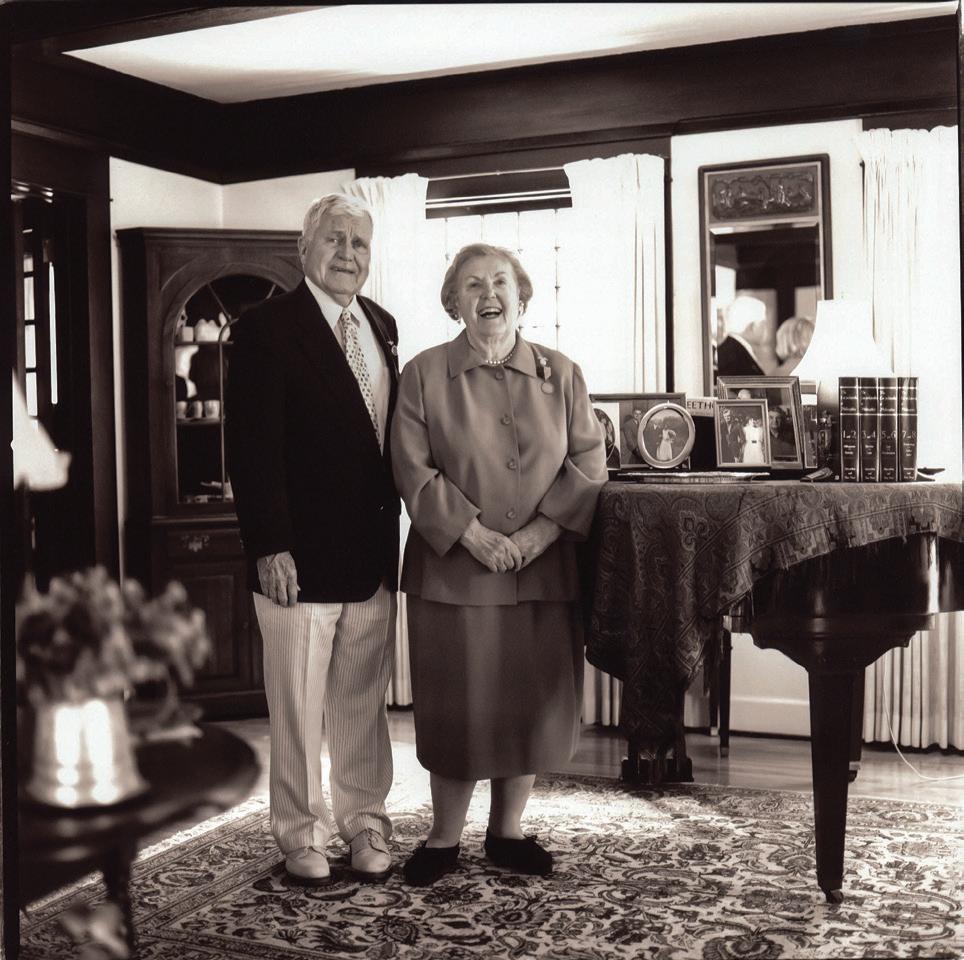

Ensch is one of 30 POWs profiled in the Coronado Historical Association exhibition “Open Doors: Vietnam POWs Fifty Years of Freedom” opening this month to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the homecoming. The photos and write-ups of the 30 men were created for the original “Open Doors” exhibit in 2003 for the 30th anniversary of their return. Displays on the men’s time in prison and the home- coming in Coronado have been added for the current exhibition.

The 30th anniversary exhibition was the project of childhood friends Taylor Kiland and Jamie Howren. Kiland is a writer and Howren a photographer.

Unlike many exhibitions on POWs, Kiland and Howren didn’t focus on the captivity, but rather how the men rebuilt their lives after living through the nightmare of prison and torture.

“Our goal was to capture each subject’s personality and redefine the lingering negative stereotype of POWs being downtrodden and suicidal. These men were incredibly successful,” said Kiland, who spent part of her childhood in Coronado and now lives in Alexandria, Virginia. Kiland, a former Navy officer, is an author and ghostwriter.

“This entire exhibition is about resilience,” said Christine Stokes, the Coronado Historical Association’s executive director. “It is what they felt at 30 years; happiness of family and a duty to give back to the nation.”

Three of the five POWs who returned to Coronado are profiled in the exhibition: Vice Adm. Edward Martin, Capt. Ernest “Mel” Moore and Vice Adm. James

What: “Open Doors: Vietnam POWs Fifty Years of Freedom”

Where: Coronado Historical Association, 1100 Orange Ave.

When: March 3 through Sept. 15

Admission: free

Information: (619) 435-7242 or coronadohistory.org

Stockdale. Capt. Harry Jenkins and Cmdr. William Stark also returned to Coronado but weren’t part of the exhibition. All five are now deceased. A lieutenant when he was shot down,

Ensch stayed in the Navy and eventually served as the commander of the Naval Training Center in San Diego before his retirement as a captain in 1995.

“I returned home having limited use of both elbows and sans a left thumb. Therefore, I had to undergo nine months of medical treatment and physical therapy before the subject of my staying in the Navy could be addressed. The decision for me for staying in the Navy was whether or not I could be returned to flight status,” Ensch recalled.

“I’m a naval flight officer and not in control of flying the aircraft. I proved to the Navy that I could still effectively and successfully operate all functions in the rear cockpit of a fighter aircraft without my left thumb. Thus, I was able to get back on flight status and continue my career. It was a fabulous feeling to get back in the cockpit and fly again.”

After he left the Navy, the now 85-yearold San Diego resident joined the San Diego Padres as director of military marketing. Howren captured him sitting in the dugout at Qualcomm Stadium, where the Padres played prior to Petco Park.

Howren, who is director of events and marketing for Lyon Air Museum in Orange County, photographed the men on film with a Hasselblad camera. The negatives were printed by hand on fiber-based paper and then sepia-toned by hand.

“We were celebrating who they were after captivity,” Howren said. “Trust was a big thing with the men. It was very organic. One interview and shoot led to another.”

Kiland got to know numerous former POWs as she volunteered for Sen. John McCain’s 2000 presidential run. At the time, most of the interviews of the men focused only on their experience as prisoners and not what they accomplished after their return, Kiland noticed.

“The POW experience influenced my perspective on life by giving me a better appreciation for life — not to take it for granted. And, to not waste it. It was almost like having died and then being given a second chance at life,” Ensch said.

“I view these men as national treasures,” Kiland said. “I continue to be in awe of the experience they went through and how physically and mentally healthy they were despite their experience.” Today only about half the men, now in their 80s and 90s, are still living.

The most surprising thing Kiland discovered was the low rate of PTSD among Vietnam POWs. According to The Robert E Mitchell Center for Prisoner of War Studies, based in Pensacola, Florida, this group of men has the lowest rate of post-traumatic stress disorder of any veterans.

Ensch attributes this to the fact that most of the North Vietnam POWS were aviators who were older, more mature and more educated. He also attributed it to leadership.

“This group maintained their military structure in captivity against all odds. And they maintained a good communication system, so the POW leadership could pass along instructions and resistance tactics. We were just continuing to fight the war in a different manner,” he said. (The prisoners used a tap code to communicate between cells.)

“Open Doors: Vietnam POWs Fifty Years of Freedom” also includes displays on the captivity and the homecoming in Coronado. Lt. Col. Tony Marshall, who was part of the original “Open Doors” project, is loaning items he kept from his time in captivity, Stokes said. Locals who remember the homecoming have had a chance to contribute their memories, photos and keepsakes.

The original “Open Doors” display is now part of the historical association’s permanent collection. After the Coronado Historical Association exhibition 20 years ago, “Open Doors” traveled the country for a year. It was then purchased by tech security company CACI International and displayed at its Virginia, headquarters. CACI has donated the display back to the historical association.

“I'd like for folks to come away from the ‘Open Doors’ exhibit with a better and more appreciative understanding of the courage, honor, commitment of and the sacrifices our military has made for this country; not only the POWs, but all who have, are and will serve when called upon to so,” Ensch said. “The military doesn’t declare war, the politicians do. The military just faithfully carries out the decisions made.” ■