30 minute read

CATCHING ON THE KANEKTOK

Catching on t he Kanektok

Catching on t he Kanektok

Life on a salmon river in full swing. By Dave Karczynski

Walrus have a penis bone Native Alaskans call an oosik—lighter in hand than a moose foreleg, it makes an excellent salmon bonker. Black bear bile can heal your liver and melt your gallstones—and get you arrested if you’re caught in possession of any. If you are encircled by griz and need to cross homicidal CFS to safety, doff your waders, trap them with air, and float to the far bank—but kiss your boots goodbye. Mullets are the most efficient haircut known to man—only the word is pronounced moo-LAY. In an essential place, one learns essential things. This July afternoon I am indeed in such an essential place— western Alaska’s Kanektok River. More precisely, I’m up to my waist in a chum salmon pool fighting my fifth fish in as many casts, this one raging like it’s just snorted a full tub of bath salts. This particularly fresh specimen has me feeling less like an angler than a matador—my buddy’s warning to wear a cup on the Kanektok was not wrong—and after charging me twice, this salmon turns on a dime and takes off in the direction of the Bering Sea. My fishing mates, Hillari Denny and Doc Rideout, groan impatiently. Though we’ve been at it only an hour, we’ve already learned that one angler tethered to a fresh chum is danger, two is a cat’s cradle, and three is a broken-rodded bird’s nest. One mottled silver rocket at a time, please.

“Must be foul hooked,” I shout, and right on cue, the fish breaches to flaunt a hook stuck squarely in its mouth. My guide chortles. Hillari and Doc shake their heads. I crank the knob on my drag and look for a similar mechanism on my arm.

The signs this would be a special trip were there the moment we debarked the plane in Quinhagak, after having flown from Anchorage to Bethel. Our shuttle was the sweetest fish ride I’d ever seen, a refurbished school bus with lightning-bolt cracks across the windshield and a rear cab stripped to make a living room–sized platform for gear. Then there was gross ubiquity of fish in every stage of life and death—leaping and torquing to shake sea lice, shotgunning through the riffles ahead of our boats, dangling from the eaves of the Native Alaskans’ smokehouses, hanging in the mouths of raptors and gulls. And finally there was our digs. There’s just something about a tent camp that speaks to the seriousness of the piscatorial endeavor. Many of my best fishing days—char in the Andes, mahseer in India, muskies in Michigan—have started with me staring up at a pitched ceiling in the dark, grasping around for my headlamp, wondering where I am. Finally my chum is in the net, and there is much rejoicing. It’s a big chrome male with sea lice for days, which earns it a driftwood bonk and free ride to the smokehouse. In no time, Hillari is rearing back into a popper-eater that makes her reel

Anchorage native Hillari Denny illustrates what a rod looks like at the doorstep of no return. Stripping streamers for chrome kings with a single-handed rod is the recipe for the best kind of disaster.

sing like a stuck pig. I watch it thrash and tailwalk as I pick a gnarly bow tie out of my running line, unaware that my fly has slipped off its guide and is dangling in the water 10 feet away. Another big chum slams it like a cheater’s first move in tug-ofwar, and I barely free my fingers before the knot squeaks tight and the fish rips downstream.

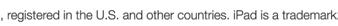

That’s another essential thing I’ve learned today: You can lose a finger on this river if you’re not careful. T he Kanektok is a seriously busy river, a conveyor belt of salmonid flesh some 80 miles long, beginning in the gunsmoke blue Ahklun Mountains and ending in Kuskokwim Bay at the Yupik town of Quinhagak, which in their language means “new river channel.” From June to September, its banks are as close to the center of the salmon universe as you can get without sprouting gills. Kings run mid-June to mid-July, chums mid-June to mid-August. Sockeyes appear in late June and do their thing until the end of the next month. Every other year, pink salmon patrol the river from mid-July to early August. Bringing up the rear of the salmon train, silvers run late July through mid-September. I’m here for the Kanektok kings, which have evolved an affinity for annihilating swung flies that is suppressed in other populations.

You can swing and strip kings elsewhere, sure. I’ve had good days on the Togiak, just a few rivers to the south, and on Great Lakes fish in my home state of Michigan. But I’ve also been in situations where the fishing fell apart just prior to my arrival because either the run was weak and the fishery was shut down or a big rain muddied the river to kingdom come. But the king runs on the Kanektok are as dependable as they are abundant, and during peak time—right around the Fourth of July, you can swing up a face cord of Chinook a day. You’d be hard-pressed to find friendlier swing water. The Kanektok falls into the Goldilocks category—not too deep and not too shallow, not too big and not too small. Competent casters giving it their all can lay up an Intruder on the far bank more often than not, and the runs average four to seven feet deep. In short, if your fly is in the water, there are probably more than a few sets of eyes on it.

That said, I am here a few weeks later, mine a gambler’s game where I’ll wager numbers of fish for specimens of frightening size: it is well known, at least here, that the last fish to come in from sea are the biggest.

There are many challenges to western Alaska king fishing. The first is abiding by the cadence of the tides. On my swing water back in Michigan, the CFS has more fixity than the stars, but the Kanektok heaves and falls to the tune of 15 feet a day. This requires anglers to use their line hand to manage the speed of the swing as a morning progresses. As the tide comes in and the current slows, a pure swing turns to a steady left-hand strip, and before you know it, you’re bringing the fly back in long, slow pulls, like some grandmother working her triceps at the gym. Then there’s the importance of using your eyes. Down in the distance, between the old moose skeleton and the abandoned snow machine, you’ll see a pod of fish breach, at which point you must throw down your sandwich or coffee or camera and make sure your fly is swimming—but not too low. The tidal bottoms have a fair amount of sediment, and kings like to swim with their chins above the murk. Finally, if you are lucky enough to get bit, the king salmon hook set asks you to be a Buddha and beast at the same time, letting the fish leisurely eat the fly and turn downstream before you drive the hook home with a pneumatic intensity—what the guides call crossing the eyes. After which, best of luck. The Kanektok has its year-round residents as well, rainbows and grayling and Dollys that spend the summer in a living hell of salmon Frogger (like the 1980s computer game) but are rewarded with endless fatty eggs to feast on in return. Given all this fishing opportunity, Kanektok days are predictable only in their unpredictability. You might start the day swinging kings before the current stalls and you hop in the boat to work the pinch points with a single-handed rod. After lunch on the bank, a chum tows you up a side channel where big rainbows with junkyard dog DNA are sulking in a pool, flesh chunks the size of a Crunch bar in their maws. This gives you a rainbow jones, so you shoot upriver to mouse the afternoon, working logjams and flushing rainbows that chomp behind your mouse as though they’ve been playing too much Pac-Man. But then another boat whooshes by, a guide traces a wavelength in the air with his free hand—meaning the tide is going back out—so you gun it back downstream to where the river meets the sea and the horizon goes on forever. In short, one things leads to another. One of our how did we get here? excursions finds us 20 miles upstream of camp, egging a side channel plunge pool where the Dollys seethe like mosquito larvae in a storm puddle. After having a mostly quiet morning, Doc Rideout unleashes a one-man “char-mageddon” catching one cartwheeling Dolly after another. I ditch my rod and instead focus on capturing some midair pictures, and while I get a few decent images, I feel more keenly than usual the limitations of the camera. The modern angler lives in an era of the photograph—some of us swipe, scroll, and tap more fish pics in a day than we used to see in a year. But after watching this “char-pocalypse,” I’m convinced that what fishing needs is not more photographs, but more sounds, not an Instagram but a Piscaphone. To hear the sizzle of the drag, the stumbling of the angler on cobble, the collective sucking in of breath when a good fish jumps, and the guide sloshing forward to stab the net. To listen to the hoots, hollers, and high fives. To behold that moment when

(Top) At dinner, as on the water, salmon are on the menu. Sockeyes get the sauté pan and some sauce. Chums enjoy a long bath in the smokehouse. (Middle) An after-dinner Dolly Varden bolts for home. (Bottom) Upper-river grayling, Dollys, and rainbows are suckers for eggs and mice. Anglers respond more favorably to a nip of whiskey.

the pool goes quiet and the angler goes quieter—that beautiful sound of an angler finally getting his or her fill.

There’s a politeness some exceptional fish grant visiting fishing writers by appearing on the last and most “fateful” day of the trip, but mine comes just past midweek. It catches me totally off guard. Not only do I not see this fish coming—no porpoising or breaching gives its presence away—but it’s also questionable whether my fly was moving when it took. Like a smallmouth taking a popper, my best king rocketed out of the water just after my fly landed. And then it took off downstream. Way downstream. When an angler suffering acute salmonitis in the shoulders, bicepses, wrists, and obliques comes upon a chromed, well-fed king salmon fresh from the sea, it’s unclear which will emerge the victor. The first few minutes of the fight are a blur. And then, slowly, I start to gain ground.

That’s when the anxiety sets in. I know I have a good fish on when I begin to fear losing it—and that fear shows. Followers of my future Piscaphone account will be able to easily distinguish between tiny fish and tremendous fish. Catching small fish, I laugh through an open smile. Catching giants, I curse through gritted teeth. After 10 more minutes—enough time for me to recite a fairly complete encyclopedia of profanity through clenched jaws—my guide motions that it is time. I do as I have been instructed all week, keeping the fish in waist-deep water—shallow water freaks them out—and lift its head just as the net harpoons forward. I stare at the fish in the net for a minute before we get out the tape measure. Forty inches. After flirting with that number all week, I have finally done it.

After a few quick pics, it was time to say goodbye, and I find a quiet, shallow flat for the release. In those last moments before letting the fish go, a familiar melancholy settles in. I’ve never been able to quite explain the feeling, which happens only on the best fish, the ones that push you to tie new creatures at the vise, the ones that keep you alert at night and very distracted at work, the ones that pull you through more airports than is decent in a single day. They are the dream that held power over you all those months and years—that is, until you are holding that dream by the tail. And then it is as if a god has fallen out of the sky in the middle of the day, and you’re watching its wings flounder as it swims in the net. There’s a sense of vulnerability in this moment of having caught the dragon, an awareness that if this impossible dream is real and mortal, then you, who are far less impossible, are real and mortal too.

Dusk is coming in purple and the river is streaming silver when my best king swims off. I am done for the day. T here’s a feeling, in the endless twilight of an Alaska summer night, of having wandered into some fashion of afterlife. You glut on king crab and strip steaks and salmon cooked three ways, then stroll back down to the river for just a few more casts before bed, which turn into a few more hours of casting. There’s something different about this extra round of fishing, when the light genuflects and the moon rises above the alders. It feels quieter, more intimate, existing apart from the everyday business of fishing. Other spirits mill about. A resident of Quinhagak arrives on an ATV to meditatively cast a spoon. A few guides slip away to egg rainbows in the permadusk. Ted Leeson once wrote that modern angling was born when certain of our ancestors, after netting and trapping and cleaning fish all day, sneaked back to the water at night with a stick and string, because they just could not stay away. Life on the Kanektok corroborates this theory, and no time more so than on the last night, when even those guests who usually go to bed after dinner find themselves waddling out to the beach and taking up a position in the run. A few guides assemble a bonfire on the beach, giving the blue mercury of the river a golden glow. Bear stories begin to circulate. One of the guides walks around with an electric hair trimmer, giving away free mullets. There are two takers. At the edge of the fire, Chum the campdog rests with chin on his paws, ears trained toward the darkening trees and what might lie beyond. Among the guests, talk turns to naming our respective highlights of the week. Answers are predictable. “My forty-pound king.” “When that twenty-eight-inch rainbow crushed my mouse.” “The day I caught one hundred pounds of fish without moving my feet.” But when it’s time for one of the older Brits to answer, he shakes his head and smiles. “All of it,” he says. “I just like catching.”

I just like catching. Catching. The intransitive act. No object. I’ve never heard the phrase, can’t tell if it’s poetry or a British commonplace, but its purity makes my head ring like a bell. Often we fly anglers fall prey to a “conoisseuership” at odds with the simplicity that fishing promises. We say things like, “I like bugging low-water smallmouths” or “I only fish the first few days of the Hex hatch.” I once saw a homemade bumper sticker that read, Tricos or GTFO. But a week on a western Alaska salmon river, when it’s in full swing, reminds even the most worldly angler what, deep down, fishing is all about.

Before heading to my tent, I walk down to the water one last time. I pick up my 8-weight and take up position in the middle of a run between a pile of driftwood and some old grizzly tracks. I’m just here to catch, I tell the river—no objective, no expectation. I make one last cast after another, on this perfect summer night, under a perfect twilit sky, in what feels like the most essential place in the world.

Dave Karczynski is the author of Smallmouth and From Lure to Fly. He lives in Ann Arbor and teaches at the University of Michigan.

(Top) There’s only one sen- sible haircut at salmon camp, and it comes free of charge. Bonus points for anyone who sticks a 30-pounder on an Intruder tied from their own hair. Tents make the most legitimate fishing homes. (Middle) Next stop, the boat launch: your airport shuttle awaits. (Bottom) In every pod of chum salmon, there are 300 fish that ignore your fly—and 5 that are looking to shank you. There’s a single motto in this situation: Keep casting.

Logistics Deneki’s Alaska West season on the Kanektok River runs from the third week of June till the end of August. On the season-long menu are all five species of Pacific salmon, plus rainbow trout, Dolly Varden, and grayling.

The first step to fishing your brains out is to get yourself to Anchorage. From there, you’ll take two shorter charter flights, one from An- chorage to Bethel, the other from Bethel to Quinhagak. Note: because the charter flights are early, you’ll need to get to Anchorage one day ahead and overnight there. Once you’re in Quinhagak, 18-foot jetboats take you upriver to the tent camp.

For outerwear, you’ll want to be fully prepared for the Kanektok weather, which even in sum- mer usually means 55 degrees and cloudy with a good chance of rain. Take plenty of wool layers, a no-fail wader–rain jacket system, such as the Simms G4s, and an oversized dry bag, like the Yeti Panga 100. Additionally, comfortable slip-on camp shoes, like the Simms Riverbank Chukka Boots, make getting from the wader room to the mess hall comfortable in all fashion of weather.

Breakfast and dinner are served buffet-style and are absolutely exquisite; shore lunches consist of sandwiches or, if you prefer, fresh fried fish. Alcohol is BYOB, with a strong message to be discreet about it. Bonus culi- nary perk: anglers can keep up to 50 pounds of salmon (excluding kings), either fresh or smoked on premises or some of each. The camp will freeze and vacuum-pack your catch for you prior to your departure.

Rates are $6,595 USD per person for a sevennight, six-day expedition. Book here and read the AK West blog: www.deneki.com.

IN YOUR QUIVER You’ll want to be packing at least three rodand-reel outfits. First and most important is a 9-weight two-handed rod for swinging kings. For this application, think Spey rods on the shorter side of the spectrum, since they tend to be better for hook-setting and leviathan fighting. My go-to stick was the 12-foot-6-inch Scott Radian in a 9-weight coupled with Rio’s InTouch Skagit Max GameChanger in its F/H/S3 rating. It was a joy to cast at medium-to-long distances, and I never felt outgunned with a good fish at the end of the line. When the tide comes in and you lose your swing, it’s time to hop in the boat, anchor above a pinch point, and cast to kings with a one-handed rod. Your 10-weight pike or muskie rod fits the bill, and this should be a beater rod, since the odds of a big king digging under the boat and snapping your stick in half are pretty much 50/50. Couple it with a 14-to-24- foot sinking tip in the appropriate grain weight, and you’re good to go.

Speaking of beater rods, you’ll want to throw your workhorse 8-weight into the mix as well, for the purpose of casting jig flies to chums on a floating line. On that note, I’ll also add that you should prepare for your week on the Kanektok like a boxer—by having a friend jam the rod’s fighting butt into your belly until you no longer feel the pain. It’s going to be that kind of a week.

UNI PRODUCTS J.G. Cote Inc. 1004 Principale, Ste-Melanie, QC. Canada J0K 3A0 Tel: 450-889-8054 Toll-Free: 1-877-889-8054 Fax: 450-889-5887 Email: info@uniproducts.com

NEW FROM UNI Email: info@uniproducts.com

NEW FROM UNI

UNI-Thread 8/0 Royal Blue Waxed or Unwaxed on spools of 50 or 200 yds UNI- French Twist Medium Gold 3 strands UNI-Thread 8/0 Royal Blue Waxed or Unwaxed on spools of 50 or 200 yds UNI- French Twist Medium Gold 3 strands

UNI-Thread 3/0 Purple and Light Orange Waxed or Unwaxed on spools of 50 or 100 yds and Light Orange Waxed

Add Digital for Only $1! See “subscriber services” at www.americanangler.com for additional details. PRINT SUBSCRIBERS

FIND AMERICAN ANGLER

FOR IPAD ™

ON THE APP STORE IN ITUNES!

HOW TO MATCH A HEX HATCH AT NIGHT PAGE 46

THE FLY FISHING AUTHORITY

SECRETS of SUCCESS SPRING CREEKS 7 of

British Spider Flies for U.S. Waters Guatemala’s Hot Sailfi sh Action

PERFECT RETRIEVES FOR ANY STREAMER INTRODUCING THE DURA-LAR BAITFISH PRO TIPS: TIE BETTER LOOP-WING DRY FLIES PERFECT RETRIEVES FOR ANY STREAMER

Visit AmericanAngler.com for details.

(Continued from page 59) Envy came loose and the fish bolted away. Henderson pondered the blank space where the fish had been.

No trip is perfect. The Green in early March is as close as I’ve come. Just to be out of the Wyoming wind was a pleasure. As luck would have it, I left my wading belt in the cliff roses where we lunched on the second day. Remarkably, Dave left his cooler full of beers, a near full jar of mayo, and enough cold cuts for two more days of floating. The water ouzels have it all now. Or maybe Hayduke came upon the spoils of our forgetfulness. He’s busy as ever now, George Washington Hayduke, fictional hero, war veteran, protector of wild rivers. He could use those beers right now, and whatever else. OVER THE BORDER

Dave Zoby is a freelance writer who splits his time between Wyoming and Alaska.

Logistics You don’t need to be Seldom Seen Smith to navigate this river, but you’d better have a good handle on the sticks, or a reasonable insurance plan. The rapids get wild in places. Best to brace in, stow your rod, pretend indifference to the crashing waves, and get through safely before trying to cast to trout. The regulations state that you must wear personal flotation devices while floating the Green. You must also have a throw rope in the boat. Live a clean life, and you’ll probably not need either of these items. Better yet, get in touch with Johnny Spillane at the Trout Creek Flies website, www.troutcreekflies.com, or call (435) 885-3355. A trip with one of his guides would be well worth the price.

The resorts and fly shops are open year-round. Though most restaurants are on hiatus, you can do as Dave and I did and pack your own fixings. Red Canyon Lodge, (www.redcanyonlodge.com), a charming, pet-friendly, locally owned operation, offers quiet cabins tucked into the piñon pines just 10 miles from the put in. Trout Creek offers hotel-style rooms and cabins, and it’s right in the middle of the action. We chose Red Canyon because we had the dogs and needed space to let them run. Merely sitting on the porch and looking at the frozen lake was worth the trip to Utah.

Out-of-state Utah fishing licenses are a bargain at $24 for three days of fishing (https://wildlife. utah.gov). Shuttles, though, are more expensive at Dutch John than, say, at the Big Horn, or other nearby famous fisheries. It was $45 to shuttle each day, from the put in to Little Hole. It’s substantially more if you want to float the lower section.

Trout are not the only game in town. Biologist Ryan Mosley talked about huge whitefish that haunt the lower sections of the river. Someone will set a new state record on this stretch, he said. These whities willingly hit shiny nymphs. Johnny Spillane talked about his newfound love of fly fishing at Flaming Gorge Reservoir in the spring and summer for bass, lake trout, rainbows, and kokanee. Something to keep in mind if you like “different.”

NOTE: Want good Utah beer? Check out Fisher Brewing Company (www.fisherbeer.com), which was originally opened in Salt Lake City in 1884. It was reopened in SLC as an employee-owned, community-focused craft brewery in 2017 with a modern and comfortable taproom. Last time we saddled up, the custom tap handles were made from cork fly rod handles, and much of the conversation revolved around local rivers and the fishing to be had there. Swing by, speak some fish, and pick up some brews for your trip to the Green. You won’t be disappointed.

(Continued from page 72) WATERLINES at the stream. I peered in and marveled at its deep, sweeping curves and its water, clear as the high-country air, lazily cutting its way across the high country.

The creek was 15 feet wide and two to four feet deep, and there were so many brook trout I couldn’t count them. When they saw me, they raced upstream to hide under roots and cuts in the steep banks. There were more trout around each bend. Most were small, just 6-to-8-inchers, but a few were over 10 inches. Their backs were broad for little trout and they were rising to everything.

I tied on my ugliest dry fly—storebought flies were a luxury I didn’t waste on broad-minded trout back then—and cast so only the leader rolled out soft onto the water. The fly landed lightly and was sucked up by the first trout that could get to it. I picked up the rod tip, and out came this gyrating little brook trout. Its colors were marbled, and its sides were sprinkled with red dots ringed by blue halos.

Each fly in my box of self-tied monstrosities—no matter how ugly—caught trout. The larger trout took time to hunt. I crawled along the meadows and cast to them so no other trout could swallow the morsel first. Before long, I had 10 sensationally beautiful brook trout, the state limit, and took them to a fire.

I would have this type of day four more times before the fleeting high-country summer was gone and I left Wyoming. Other trips over the next two decades took me to Wyoming and elsewhere, but there never was time to hit that stream again. Twenty-one years later, I got the chance . . . and wondered if I should take it. “You can’t go back,” said Bill Buckley, a friend, when I saw him in Bozeman a few days before my trip. I told him I had to, even if it meant heartbreak.

I drove down through the middle of Wyoming, onto the high plains, then past Lander to Medicine Bow, home of the Virginian Hotel, and onward to Saratoga, a town the North Platte takes a turn through before going off north into the sage.

The town of Encampment, just south of Saratoga, felt windswept and desolate, tucked up near the Snowies and right up against the Sierra Madre. I remembered watching a play there, written by locals and put on in a drafty town hall on a winter night as part of a celebration of the town’s 150th anniversary. The town was founded as a meeting place for fur trappers. The night of the play the whole town seemed packed into that building, and the laughter was so hearty I thought the whitewashed wallboards might vibrate off. I stopped on the main street at midday and watched two mule deer bucks saunter between boardedup stores without a person in sight.

The road rose into tan foothills that became beetle-killed pine forests. The sagecovered high-country desert fell away. The road wound on, and at the top was a small parking lot. Below, to the south and west, mountains drifted into Colorado.

The parking lot had been expanded and a bathroom added. Locals unloaded dirt bikes. An off-road trail is there now. I pictured those loud things doing wheelies over my once sacred stream and almost turned around and left.

I took a deep breath and stepped out of my rented SUV and felt the sun chasing away a chill on that July morning. The bright sun felt luxurious and the forest smelled of pine.

On the hike in I had to step off the trail twice to avoid dirt bikes screaming by. But I kept on to where the off-road trail turned north and the mountain descended east. I saw the rivulet in the trees running through all the wildflower meadows. I followed the stream and found it still jumping with tiny brook trout. The sound of the motorbikes had faded away. Soon, through an opening in the trees, I saw the valley. I could see a shining ribbon of a stream winding quietly, outside of time. The same copses of fir trees were standing around the same bends. The water was still deep and as clear as the high-country air. In the top of each pool were brook trout in bunches, watching the water above, all waiting for the insects in the grass to misjudge a leap and fall into the stream.

I tied my ugliest dry to the tippet and cast, and a trout rose. In a flash, a brookie was out of the water and in my hand like a memory in flesh. It was everything I remembered and nothing I didn’t.

Frank Miniter is a New York Times best-selling author who lives near the famed trout streams of the Catskill Mountains. See more of his work at www.frankminiter.com.

P.O. Box 475 Twin Bridges, Mt. 59754

800-222-5510 • www.kings atline.com CUSTOM PACKAGES: GUIDES, LODGING, MEALS Professionally guided oat and wade trips on the Big Hole, Beaverhead, Jefferson, Madison and Ruby rivers & spring creeks. Call for Rates and Brochures. Flatline Outfi tters & Guide Service: Matthew A Greemore (Lic. # 4005) Cell: 406-596-2036

Cast Out Clutter. Renew Online! Sign up to receive all

subscription renewal notifi cations via e-mail instead of U.S. mail.

It’s fast, easy and earth friendly! Visit www.americanangler.com for details.

Never Go Back

THAT POND WHERE YOUR first bass sucked in a worm and tugged under the bobber just before you felt the stupendous weight of a fish on some flimsy kid’s pole. Or that freestone stream where your first trout rose to a fly with your dad watching and smiling . . . Well, those places are best left to memory. What you felt there, with your father or siblings, or good friends, is too special to tread on. If you do go back, you’ll find someone built a home blocking access to the water. You’ll see posted signs nailed to trees. You’ll discover the pond has silted in. Maybe you’ll just find it smaller, with less mystery and appeal than you recall. Or you’ll see your father or other loved ones now gone, and will be too melancholy to enjoy that sacred place. You may leave shattered. It would be like seeing your high school sweetheart and not recognizing her until she tells you her name. So don’t go back. Not now. Not ever. Well, that’s what they say. There was this high-country Wyoming stream I knew when I was 24. I was a reporter at a small-town daily newspaper. My salty editor, Chuck Bowles, a man the bottle would kill in the old-fashioned way, said to me: “So you fly fish. Well, boy, if you like brookies, I’ll give you a spot. It’s a meadow stream straight from a Robert Frost poem. Well, if Frost knew about Wyoming.

“There is no trail,” he warned. “So, park at the Continental Divide up in the Sierra Madre, south and above Encampment. Hike southeast over parks and through aspen stands and follow one of the rivulets down the mountainside to the North Fork of the Encampment. Now, get out of my sight.”

I found the stream, but not until after I went the wrong way down the pinedarkened mountain, thanks to Bowles’s vague directions, and ended up at a great (Continued on page 71) brook trout lake. But it bothered me that I hadn’t found the stream. I knew my editor would ask about it.

Back up the mountain I went, powered by my 24-year-old legs. Once on top, I followed a rivulet that was just two feet wide, a tiny stream jumping with puny brook trout—just as Chuck described—and then went down the mountain’s east side. The little brook fell through fields of wildflowers— white March marigold, red Indian paintbrush, yellow hoary balsamroot—until the valley opened in yellow light at the bottom. There was long grass moving lightly on soft summer wind. There were bunches of firs. Under the firs was moss so thick you wanted to lie on it and look up into the branches and listen to the water going by as you forgot that time is fleeting. In early afternoon I walked into the warm sunlight that bathed those 10,000-foot-high meadows and stopped

The all new

A whole new level of high performance handcrafted fly rods.

Scott Sector series fly rods are packed with innovative new technologies, and are crafted with the most cutting-edge components to ever grace a fly rod.

To see more of the Sector Series, or learn about our new Carbon Web and Ceracoil, visit scottflyrod.com or your nearest authorized Scott fly shop.