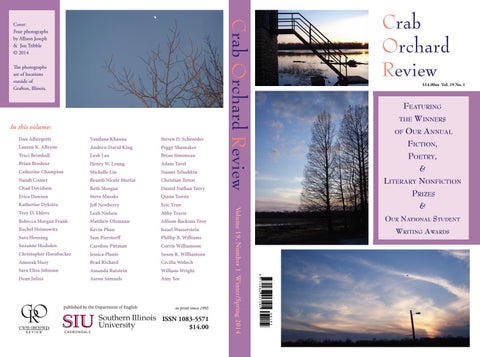

The photographs are of locations outside of Grafton, Illinois.

In this volume: Steven D. Schroeder

Andrew David King

Peggy Shumaker

Traci Brimhall

Leah Lax

Brian Simoneau

Brian Brodeur

Henry W. Leung

Adam Tavel

Catherine Champion

Michelle Lin

Naomi Telushkin

Nandi Comer

Brandi Nicole Martin

Christian Teresi

Chad Davidson

Beth Morgan

Daniel Nathan Terry

Erica Dawson

Steve Mueske

Qiana Towns

Katherine Dykstra

Jeff Newberry

Eric Tran

Troy D. Ehlers

Leah Nielsen

Abby Travis

Rebecca Morgan Frank

Matthew Olzmann

Allison Backous Troy

Rachel Heimowitz

Kevin Phan

Israel Wasserstein

Sara Henning

Sam Pierstorff

Phillip B. Williams

Suzanne Hodsden

Caroline Pittman

Corrie Williamson

Christopher Hornbacker

Jessica Plante

Susan R. Williamson

Amorak Huey

Brad Richard

Cecilia Woloch

Sara Eliza Johnson

Amanda Rutstein

William Wright

Dean Julius

Aaron Samuels

Amy Yee

C

R AB •

ORCH AR •

REVIEW

D

in print since 1995

ISSN 1083-5571 $14.00

Featuring the Winners of Our Annual Fiction, Poetry, & Literary Nonfiction Prizes & Our National Student Writing Awards

00191

CO R

published by the Department of English

$14.00us Vol. 19 No. 1

9 771083 557101

Vandana Khanna

Lauren K. Alleyne

Volume 19, Number 1 Winter/Spring 2014

Dan Albergotti

Crab Orchard Review

Crab Orchard Review

Cover: Four photographs by Allison Joseph & Jon Tribble © 2014

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A Journal of Creative Works

Vol. 19 No. 1

“Hidden everywhere, a myriad leather seed-cases lie in wait…” —“Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” Thomas Kinsella Editor & Poetry Editor Allison Joseph

Founding Editor Richard Peterson

Prose Editor Carolyn Alessio

Managing Editor Jon Tribble

Editorial Intern Desiree Young

Assistant Editors Emily Rose Cole Loren Elise Foster M. Brett Gaffney Austin Kodra Zach Macholz Philip Martin Alyssha Nelson Staci R. Schoenfeld

SIU Press Interns Austin Kodra Philip Martin Board of Advisors Ellen Gilchrist Charles Johnson Rodney Jones Thomas Kinsella Richard Russo

Winter/Spring 2014 ISSN 1083-5571

Special Projects Assistant Cole Bucciaglia

The Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Address all correspondence to:

Crab Orchard Review

Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901 Crab Orchard Review (ISSN 1083-5571) is published twice a year by the Department of English, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Subscription rates in the United States for individuals are $25 for one year, $40 for two years, $50 for three years; the foreign rate for individuals is $40 for one year. Subscription rates for institutions are $28 for one year, $56 for two years, and $84 for three years; the foreign rate for institutions is $48 for one year. Single issues are $12 (please include an additional $10 for international orders). Copies not received will be replaced without charge if notice of nonreceipt is given within four months of publication. Six weeks notice required for change of address. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Crab Orchard Review, Department of English, Faner Hall 2380 Mail Code 4503, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 1000 Faner Drive, Carbondale, Illinois 62901. Crab Orchard Review considers submissions from February through April, and August through October of each year. Please visit our website, CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu, for the latest guidelines, calls for submissions, and contest information. Most of our submissions are now through CrabOrchardReview.submittable.com, so please do not send submissions via postal mail unless you are certain we are open for postal submissions at that time. Crab Orchard Review accepts no responsibility for unsolicited submissions and will not enter into correspondence about their loss or delay. Copyright © 2014 Crab Orchard Review Permission to reprint materials from this journal remains the decision of the authors. We request Crab Orchard Review be credited with initial publication. The publication of Crab Orchard Review is made possible with support from the Chancellor, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Department of English of Southern Illinois University Carbondale; and through generous private and corporate donations. “Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois,” 27 June 2014, 3900 copies printed, order number 114043. Lines from Thomas Kinsella’s poem “Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” are reprinted from Thomas Kinsella: Poems 1956-1973 (North Carolina: Wake Forest University Press, 1979) and appear by permission of the author. Crab Orchard Review is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Visit Crab Orchard Review’s website:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

Crab Orchard Review and its staff wish to thank these supporters for their generous contributions, aid, expertise, and encouragement: Barb Martin, Karl Kageff, Amy J. Etcheson, Bridget Brown, Lynanne Page, Angela Moore-Swafford, Wayne Larsen, and Kristine Priddy of Southern Illinois University Press Heidi Estel, Patty Norris, Joyce Schemonia, and Kelly Spencer Abby Allen, Shaylin Carlton, Kevin Savoie, and Savannah Broadway Dr. K.K. Collins (chair), Pinckney Benedict, Beth Lordan, Judy Jordan, Scott Blackwood, and the rest of the faculty in the SIUC Department of English Division of Continuing Education SIU Alumni Association The Graduate School The College of Liberal Arts The OfďŹ ce of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost The Southern Illinois Writers Guild

Crab Orchard Review is supported, in part, by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency.

Crab Orchard Review wishes to express its special thanks to our generous Charter Members/Benefactors, Patrons, Donors, and Supporting Subscribers listed on the following page whose contributions make the publication of this journal possible. We invite new Benefactors ($500 or more), Patrons ($200), Donors ($100), and Supporting Subscribers ($50) to join us. Supporting Subscribers receive a one-year subscription; Donors receive a two-year subscription; Patrons receive a three-year subscription; and Benefactors receive a lifetime subscription. Address all contributions to:

Crab Orchard Review Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901

CHARTER MEMBERS*/BENEFACTORS Rodney Jones Richard Jurek Joseph A. Like Greg & Peggy Legan* Beth L. Mohlenbrock* Jane I. Montgomery* Ruth E. Oleson* Richard “Pete” Peterson Peggy Shumaker

Carolyn Alessio & Jeremy Manier Pinckney & Laura Benedict Edward Brunner & Jane Cogie* Linda L. Casebeer Dwayne Dickerson* Jack Dyer* Joan Ferrell* John Guyon* John M. Howell*

PATRONS Diann Blakely Robert E. Hayes Kent Haruf Chris Kelsey Jesse Lee Kercheval Lisa J. McClure

Anita Peterson Eugenie & Roger Robinson Nat Sobel Betty & Ray Tribble David & Laura Tribble Clarisse Zimra

DONORS Lorna Blake Chris Bullard Heidi Czerwiec Charles Fanning Jewell A. Friend John & Nancy Jackson Reamy Jansen Rob & Melissa Jensen Elisabeth & Jon Luther

Charlotte and Gabriel Manier Lee Newton William Notter Lisa Ortiz Ricardo Pau-Llosa Lucia Perillo Angela Rubin Hans H. Rudnick William E. Simeone

SUPPORTING SUBSCRIBERS Serge & Joan Alessio Joanna Christopher K.K. Collins Corrine Frisch John & Robin Haller Zdena Heller Karen Hunsaker Lee Lever

Charlotte McLeod Peggy & Albert Melone Nadia Reimer Lee Robinson Catherine Rudnick Peter Rutkoff Victoria Weisfeld

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

Winter/Spring 2014

Volume 19, Number 1

Fiction 1

Troy D. Ehlers Suzanne Hodsden

Five Deaths of Ellie Marsh Dead Boy’s Wedding

28

Beth Morgan

Default Setting

58

Naomi Telushkin

Judah

71

Nonfiction Prose 99

Katherine Dykstra

Like Held Breath

Leah Lax

Water of Sleep

112

Henry W. Leung

Quitting the Box

143

Abby Travis

They Say

152

Allison Backous Troy

Inertia

186

Amy Yee

Deckyi’s Journey from After Tibet: Exile in India

193

Poetry Dan Albergotti

Holy Night

14

Lauren K. Alleyne

How to Watch Your Son Die Killed Boy, Beautiful World

16 18

Traci Brimhall Brian Brodeur Catherine Champion

In My Third Trimester, I Dream My Own Death

19

Blight

20

Caliban, After

22

Nandi Comer

The Warning Detroit, Llorona, My Heart, My City Losing Between Manholes and Myths

23 24 26

Chad Davidson

In Ravenna The Gothic Line

41 42

Erica Dawson

Midget Wrestling at the Dawg House, Portales, NM

44

Rebecca Morgan Frank

Evolution

45

Rachel Heimowitz

What the Light Reveals

46

Sara Henning Christopher Hornbacker Amorak Huey

Losing a Child

49

Birding

50

North of Dowagiac the Human Body Is 98 Percent Winter

52

Sara Eliza Johnson

Deer Rub

54

Dean Julius Vandana Khanna

Augur 56 Parvati Rewrites Myth

57

Andrew David King

On Taking Down the Model Airplanes from Your Bedroom Ceiling

86

Michelle Lin

Roundtrip

88

Brandi Nicole Martin Steve Mueske

First Elegy for His Child I’ll Never Have 90 Poem That Forgets It’s a Poem

91

Jeff Newberry

How to Talk About the Dead Spring’s Return About Disappointment

93 94 95

Leah Nielsen

Tuscaloosa Poem

96

Matthew Olzmann

You Want to Hold Everything in Place, But

98

Kevin Phan

Night Bells in a Landscape

126

Sam Pierstorff

At the Hotel of Irrelevancy

128

Caroline Pittman

Easter Poem

130

Jessica Plante

Descendants

132

Brad Richard

Confederate Jasmine

133

Amanda Rutstein

Ruined

134

Aaron Samuels

Stakes is high

136

Steven D. Schroeder

Nuclear

138

Peggy Shumaker

Past Middle Age

140

Brian Simoneau

Sonnet for the Guy Who Told Me My Dad Was a Saint

141

Adam Tavel

Elegy for Phineas Gage Posing in a Daguerreotype Portrait

142

Christian Teresi

For the Kingdom to Be Well

165

Daniel Nathan Terry

There Is No Way The Boy and the Moth

166 167

Qiana Towns

Voyeurism

168

Eric Tran

Our Own Little Gods

170

Israel Wasserstein

Paleontology

171

Phillip B. Williams

Liner Notes to a Never-Composed Session for A Love Supreme Of Shadows and Mirrors

173

Corrie Williamson

Umbrage

176

Susan R. Williamson

Conjugal Fault

178

174

Cecilia Woloch Istanbul Teta Afterlife

179 180 182

William Wright

183

Triptych for the Days Before Her Passage

Contributors’ Notes

200

A Note on Our Cover The four photographs on the cover are by Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble. All of the photographs were taken at locations outside of Grafton, Illinois, near and in Pere Marquette State Park around the conf luence of the Mississippi River and the Illinois River.

Announcements There were significant awards and honors this Spring for four poets published in the Crab Orchard Series in Poetry: Honorée Fanonne Jeffers and Jake Adam York were honored as the 2014 Witter Bynner Fellows selected by the 19th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry at the Library of Congress, Natasha Trethewey. Denise Duhamel and Jeffrey Skinner are recipients of 2014 Fellowships in Poetry from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. And we are very proud to congratulate former Crab Orchard Review intern and assistant editor and Southern Illinois University Carbondale MFA alumnus Adrian Matejka on his recent awards and honors, including being named a finalist for the 2013 National Book Award in Poetry and being cited as a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for his collection The Big Smoke (Penguin Poets/Penguin Group). The Big Smoke is also one of the winners of the 2014 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards, which “recognize books that make important contributions to our understanding of racism and human diversity.” And in addition to these honors, Adrian is also a recipient of a 2014 Fellowship in Poetry from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

The 2014 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize We are pleased to announce the winners and finalists for the 2014 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize. In poetry, the winning entry of three poems—“Detroit, Llorona, My Heart, My City,” “Losing Between Manholes and Myths” and “The Warning”—is by Nandi Comer of Bloomington, Indiana. The judge selected three finalists in poetry, and they are three poems by Lauren K. Alleyne of Dubuque, Iowa; three poems by Jeff Newberry of Tifton, Georgia; and three poems by Cecilia Woloch of Los Angeles, California. In fiction, the winning entry is “Five Deaths of Ellie Marsh” by Troy D. Ehlers of Wayzata, Minnesota. The judge selected two finalists in fiction, and they are “Dead Boy’s Wedding” by Suzanne Hodsden of Bowling Green, Ohio; and “Default Setting” by Beth Morgan of Lawrenceville, New Jersey. In literary nonfiction, the winning entry is “Inertia” by Allison Backous Troy of Laramie, Wyoming. The judge selected three finalists in literary nonfiction, and they are “Like Held Breath” by Katherine Dykstra of Brooklyn, New York; “Water of Sleep” by Leah Lax of Houston, Texas; and “They Say” by Abby Travis of Somerville, Massachusetts. The final judge for the poetry competition was Allison Joseph, Crab Orchard Review’s editor and poetry editor, and the final judge for the fiction and literary nonfiction competitions was Carolyn Alessio, Crab Orchard Review’s prose editor. All three winners received $2000.00 and their works are published in this issue. Several of the finalists also chose to have their works published in this issue. Congratulations to the winners and finalists, and thanks to all the entrants for their interest in Crab Orchard Review. Crab Orchard Review’s website has information on subscriptions, calls for submissions and guidelines, contest information and results, and past, current, and future issues:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

The Winners of the 2014 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize

2014 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize Winner

Three Poems by Nandi Comer (Bloomington, Indiana)

2014 Jack Dyer Fiction Prize Winner

“Five Deaths of Ellie Marsh” by Troy D. Ehlers (Wayzata, Minnesota)

2014 John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize Winner

“Inertia” by Allison Backous Troy (Laramie, Wyoming)

The 2013 COR Student Writing Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction The COR Student Writing Awards in Fiction, Nonfiction, and Poetry honor the exceptional creative work of undergraduate and graduate students who are enrolled at least part-time in a U.S. college or university. Each winner receives $500.00 and publication in Crab Orchard Review. The 2013 Allison Joseph Poetry Award winner is “On Taking Down the Model Airplanes from Your Bedroom Ceiling” by Andrew David King (University of California, Berkeley). We would also like to congratulate the finalists for the 2013 award: “Bird Without a Feather” by P. J. Williams (University of Alabama); “Crawfish” by Tina Mozelle Harris (University of Oregon); “The Crickets Remember” by Maggie Graber (Southern Illinois University Carbondale); “Father and Son” by Tim Payne (University of West Georgia); “Painting Moreno Valley” by Joel Ferdon (McNeese State University); “Sex-Ed” by Anna Rose Welch (Bowling Green State University). The 2013 Charles Johnson Fiction Award winner is “Judah” by Naomi Telushkin (Arizona State University). We would also like to congratulate the finalists for the 2013 award: “Bottled Chaos” by Lauren Sarazen (Chapman University) “Chasing a Leak” by Casey Pycior (University of Nebraska-Lincoln); “Homeland” by Christopher Linforth (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech)); “Nine Stories Tall and Hollow” by Lindsay D’Andrea (Iowa State University); and “What May or May Not Matter” by Linda Miller (Queens University of Charlotte). The 2013 Rafael Torch Literary Nonfiction Award winner is “Quitting the Box” by Henry W. Leung (University of Michigan). We would also like to congratulate the finalists for the 2013 award: “1,000 Wednesdays” by Danielle Harms (George Mason University); “Amblyopia” by Lena Moses-Schmitt (Virginia Commonwealth University); “Cries for Life” by Kevin Davis (Northwestern University); “Crucifixion Style” by Joel Newsome (Western Michigan University); and “Who You Know” by Jessie Szalay (George Mason University). For more information about the COR Student Writing Awards and the past winners, and about Allison Joseph, Charles Johnson, and Rafael Torch, visit:

CORStudentWritingAwards.siu.edu

The 2013 COR Student Writing Award Winners

2013 Allison Joseph Award Winner

“On Taking Down the Model Airplanes from Your Bedroom Ceiling” by Andrew David King University of California, Berkeley (Berkeley, California)

2013 Charles Johnson Fiction Award Winner

“Judah” by Naomi Telushkin Arizona State University (Tempe, Arizona)

2013 Rafael Torch Literary Nonfiction Award Winner

“Quitting the Box” by Henry W. Leung University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, Michigan)

Troy D. Ehlers Five Deaths of Ellie Marsh The first time I see Ellie die, she is dancing around the living

room on the balls of her feet, singing at the top of her lungs and laughing whenever her voice squeaks or she messes up the words. Her brown eyes glisten and her body moves with the grace of tall grasses bending in the wind. Her arms move with the music, waving slowly up and down as though she imagines she will take flight. As though she can simply bypass the mundane banality of death: the dizziness; the cold and aching limbs; the painful stomach cramps; the brain muddled; the lungs heavy and sluggish, too weak to breathe. Ellie will have none of that. She will simply cast aside her earthly existence. She will slip free of her body like a butterfly from a cocoon. This first death is one of denial. I could not accept that Ellie was dead. I knew she had killed herself. She was gone. But I could not bring myself to believe that all the beauty and joy she’d emanated had been extinguished. Even though she was deeply troubled and at times could be cruel and nearly violent, in the days after I learned of her suicide, I could not think of her suffering. I wanted to believe she had died with the same grace and beauty she’d had in life. This was the only way I could have imagined her death. She is wearing the white dress with the red flowers. The one she’d worn when I’d seen her last, months ago at her home in Wisconsin. She looked radiant then, too, happy and beautiful as she drank her wine and laughed at some joke Jan’s husband had told. Even then my heart broke a little each time she laughed—her cheeks dimpling, her tongue curling up to touch her lip. Her laughter always managed to seem both hardy and fragile at the same time. I’d always expected she’d be laughing, even in the end. She turns up her stereo and swallows the pills a half-dozen at a time, washing them down with a bottle of Australian shiraz. I don’t know what she’s taking, but it makes sense that she’s using pills because she is conscious of her beauty. She can be insecure and fish for compliments, for reassurance that she isn’t getting fat or old, but she knows she is Crab Orchard Review

u 1

Troy D. Ehlers striking. Gorgeous, in fact. She’d won a beauty pageant as a teenager and modeled during college. So even as she plotted her own death, she must have thought ahead to the funeral; she wouldn’t want a closed casket, wouldn’t want some ghastly corsage strapped to her wrist to cover a razor’s slash. And perhaps this irony is what starts her laughing now. She has polished off the pills and a good portion of the wine. She is dancing around the living room, enjoying the burning friction of her toes on the carpet as she spins. The dress floats up around her waist. The mirror over the couch spins past and she laughs as she announces: “I’ll be lovely in my coffin! Even at my wake, they’ll be jealous!” She laughs at herself and feels dizzy and nauseous. She stops, kneels, and lies on the floor, careful with the wine. On her back, she looks up and remembers how she’d played with her sister as a child—she pretends the ceiling is really the floor and the floor is the ceiling. She swims along the carpet, imagining she is flying, imagining she has already grown her wings. I received two calls that evening. The first was from Jan, the second Delinda. By nature women know how to handle such tragedies. They know when you need a hug or soothing words or a bolstering compliment. They can be cruel and cut you to shreds with a word, but they are angels. Call it maternal instinct. Jan phoned first to break the news of Ellie’s suicide. Then I was given just enough time to get my mind around the horrible reality—but not so much time that I would be swallowed by grief or self-blame. When Jan had told me what happened, everything went gray. She kept talking, but her words didn’t register. She might have told me the details of the suicide, but I wasn’t able to hear them. By the time Delinda called, I’d forced myself to accept Ellie’s death, but I conceded nothing beyond a dancing, easy, laughing death. I nearly asked Delinda how Ellie had actually died, but the words wouldn’t come out of my mouth. Delinda lived just forty-five minutes away, south of Minneapolis. She asked whether I wanted company and invited me to dinner with her husband and daughter. Pizza and hot fudge sundaes, she said. Comfort food. When I declined, she worried about my being alone. She tried to get me to reminisce with her about Ellie’s exploits in the Venezuelan village south of Caracas; that was where we’d all met, the dozen of us, and became friends on a volunteer mission to build an orphanage. “Remember,” Delinda said, “when she did body shots off my stomach and danced on the bar while the bartender yelled at her?” 2 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers “He wasn’t yelling at her,” I said. “He climbed up and danced with her.” I remembered because I’d been jealous. “Oh that’s right! He kept slicking back his greasy hair and winking at her,” Delinda laughed. “And later she was dancing outside on that muddy path when she slipped.” “She nearly slid down the mountain.” Delinda’s laugh was loud—it verged on becoming a wild cackle— but I recognized the grief behind it. “What I remember most was Ellie with the children,” Delinda said. “She connected with them. Made them laugh. I always felt like a spectacle in a fishbowl whenever the kids watched us work. I’d try to talk, but it was hard enough to communicate, let alone entertain children.” “She was one of them,” I said. “A kid at heart.” Delinda agreed, but I knew she didn’t fully understand. Ellie was known for her contagious laughter and scandalous behavior, but she could be wise, mature, and sometimes (albeit rarely), she could even be a good listener. But as I came to know her, I discovered she mimicked those around her. She said smart things to smart people. She listened well for good listeners. She had learned how to act maturely, but deep down, for good or for bad, she was a child. And so when she took to playing with children from the orphanage and getting them to aid in the construction, the rest of us believed she was making profound use of psychology to reach them; she was instilling in them a sense of pride because they would live in a place they had built with their own hands. To the children she became La Presidente. Every couple days, she rewarded one of them with the rank of El Capitán. The new captain got to wear Ellie’s Chicago Cubs cap (bearing its ‘C’ for Capitán) and preside over the other children (her soldados, her soldiers). Two or three times a day, Ellie whistled and the children lined up for roll call, inspection, and to report their progress. In the evenings, Ellie and the children ran off into the trees to play tag, hide and seek, or war. Once, while exploring a path through the trees, I stumbled across Ellie lying on her stomach, concealed beneath a canopy of daggershaped leaves. She shushed me. She grabbed my arm and pulled me to the dirt beside her. When I brushed at a stream of ants crawling up my arm, Ellie whispered, “Shhhh. I can hear him.” I was about to ask who when I spotted her current capitán, stalking through the trees with a long stick held to the crook of his arm like an assault rifle. The boy scanned the trees and moved along in a crouch. He stopped at a suspicious plant and poked it with his Crab Orchard Review

u 3

Troy D. Ehlers rifle before moving on. Gradually, as the boy vanished in the distance, a broad smile crept onto Ellie’s face. I was captivated by the delicate smile-lines feathered around her eyes, the sharp blade of her nose, the mischievous dimples of her cheeks. Her mahogany hair was tucked back behind her ear, which had three piercings but no jewelry. A bead of sweat trickled from her forehead. I leaned over and kissed her cheek. When she turned to me, I was relieved by her smile, unfaded. I hadn’t expected to kiss her. I had found her attractive but thought her beyond reach. If there was a right move to make next, I had no idea what it was. I waited for her reaction. Her eyes opened wider and, ever so slowly, her mouth stretched from a smile into an ‘O.’ Then she glanced over my shoulder and yelled, “Aww, biscuits!” She scrambled to her feet, laughing. The capitán had doubled back behind us. I watched her run off, chased into the jungle. My kiss had meant nothing. I had only kissed her while she was being a child. “Ellie was an angel,” Delinda said. A painful knot formed in my throat. “Look, Delinda. Thanks for calling, but I’m not ready to talk about her. Not in the past tense. I’m not ready to.…To reminisce.” “I know you loved her, Michael. And she loved you. There’s no shame in that.” After I set down the phone, I wondered what she’d meant about shame. I’d felt only shock. Shame hadn’t even occurred to me. The word struck up in me a whirlwind of self-doubt. Was Delinda referring to the way my affair with Ellie had begun? Was she suggesting that I could have saved her? That I should have been there for her—not just in the end, but during the entire time since her divorce? Ellie might have been vulnerable when we met. She was in the midst of a trial separation from her husband. Then again, she could have been at her strongest and most liberated. At times it seemed she was both. During our village orientation, she had been so withdrawn that I was barely aware of her—a shadow lurking at the back of a classroom. She sat with her head bowed low over her desk, disheveled hair draping her face as she scribbled in a pink notebook. I was the first person to actually talk to her. At the end of our first day of labor, she came upon me, my hands ghostly white with plaster dust, reading poems by Pablo Neruda. She remarked that she liked his work and began sidling away shyly, but I stopped her, asking whether she had a favorite. Her face lit up and she seemed surprised that somebody would take an interest in her. El mar y las campanas 4 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers was her favorite collection, The Sea and the Bells—Neruda’s last. She quoted the opening lines of the first poem, in well-practiced Spanish. Time passes not hour by hour, but sorrow by sorrow. We became inseparable, and during the following days, her attitude cycled through extremes. In the mornings, she was quiet and sullen, but her mood could shift unexpectedly (and often dramatically) and together we would be seized by fits of laughter. Eventually I realized that her capricious and transient nature was part of what I found attractive—she could be dark, mysterious, puzzling, and even childlike; perhaps I had remained a bachelor only because I needed such instability (she was anything but static—her legs were always moving, tattooing some unheard beat, even as her mood vacillated from dark to light). Ellie rarely slept—just an hour or two each night— and one night (after we’d grown much closer), I sensed her pretending to sleep, her breathing intentionally slow and regular, her body unnaturally stiff. When she thought I was asleep, she slipped from the bed, gathered her clothes, and tiptoed outside. I thought to follow her, but she returned and shook me. She led me out to the hillside. A full moon cast serpentine shadows in the mist-blanketed valley. Strange animal calls sounded from the trees. She pulled my head down and kissed me ferociously. Ellie made a brave effort to hide her darker moods. She wandered off to cry in solitude or vent her rage by jogging narrow paths along the river. She’d always tried to put on a smile for me. I thought it was the separation, but she suffered from bipolar disorder. Occasionally she would start an argument or tell me how miserable she was, but I never had more than a glimpse of her true anguish. I wished she’d shared her darker emotions. I could have been a shoulder to cry on. Maybe—somehow—I could have helped. When the phone rang again, I was torturing myself with the image of her crying alone in a darkened bedroom. “Michael, are you crying?” It was Cindy. She sounded angry. I wiped my eyes and said nothing. “You better not be crying. That bitch doesn’t deserve your tears.” Cindy had joined us several days late in Venezuela. She was Ellie’s sister-in-law. The idea of a woman on a trial separation traveling with her sister-in-law probably seems bizarre, but Cindy was not bound by social mores. No one dictated who her friends should be and she saw no conflict between her allegiance to her brother and her friendship with Ellie. Perhaps even more remarkable, she befriended me despite Crab Orchard Review

u 5

Troy D. Ehlers the affair I was having with her brother’s wife. As Cindy herself once put it: “I like who I like.” She also said what she meant. “She doesn’t deserve your sympathy,” Cindy said. I cleared my throat. I didn’t know what to say. “She kept leaving little hints, little suggestions that she was suicidal. How dare she do that to me? Leave that hanging over me?” “She told me, too. It wasn’t just you.” “She fucking knew better! She knew we would feel guilty. She couldn’t pass up one last chance to manipulate us. To twist the knife in the wound.” “She was just hurting inside,” I said. “Finalizing the divorce was the final straw for her.” “Oh, don’t be naïve. It was all a big game for her, seeing how far she could bend people out of shape and suck them into her dramas.” “I don’t want to hear this,” I shouted into the phone. “I miss her, dammit! Don’t you get that? I loved her. Think of my feelings!” “Ellie’s the one who didn’t give a damn about your feelings,” Cindy said. “She’s the one who did this to you. She was incapable of love. And what about her son? Her mother? Her ex-husband, me, and all of her friends.…She sandbagged us all.” “She just didn’t think she was good for us. She thought we’d be better off—” “Don’t give me that bullshit. Ellie was a bitch and I hate her for doing this! We’re all pissed at her, Michael. It’s not just me. Don’t cry over that heartless piece of crap!” I slammed the phone down on the counter, picked it up and slammed it down again and again. I shook with rage. I bit my lip and tasted blood. I stood up, toppling my stool behind me. I kicked it away and punched the wall. The phone rang again, so I unplugged it. When the answering machine began spewing my inane greeting, I unplugged that, too, and hurled it across the room. The rage burned in me, every muscle clenched and trembling. I wanted to turn my fury on the world. I wanted to break things. I wanted to hurt somebody. I kept thinking of what Cindy had said about others hating Ellie. No wonder Ellie had felt so alone, with such fickle turncoat friends. I was the only person who’d loved her, and everybody thought it wrong of me to care. Ellie and I should have stood together, united against this selfish, uncaring world. I grabbed a couple bottles of beer and flipped channels on the TV. I wanted to see 6 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers something violent. Nothing was violent enough. Every false, bleachtoothed grin deepened my isolation and anger. I drank and hurled the bottles against the fireplace. An hour later my world was spinning as I sank into unconsciousness. Shards of glass had landed on the couch, scratching me as I tossed about. I remembered Ellie’s foul moods and wicked temper. I remembered our fights. I remembered her shame and grief at having fought with her husband in front of her son. Ellie is shouting but I cannot hear her voice. Spittle flies from her lips. Tendons protrude from her neck. Her face reddens. She chops her arms through the air as she confronts her ex-husband and the young woman in the blue halter top. The girl lunges toward her, but Ellie’s ex grabs the girl’s wrist—just above the rubber bracelets popular among teenagers. He yells for them to calm down. Ellie is furious. She was bringing her son Tommy home at the end of a weekend and found them making out on the couch. He’s done it on purpose, to make her jealous. He’s always trying to hurt her. Ellie grabs a remote from the end table and hurls it at them. It bounces off his shoulder and he cringes. Between them, Tommy leans against the wall, crying and clutching his duffel bag to his chest like a life preserver. He sobs and begs his mommy and daddy to stop. Ellie grabs a black picture frame and sails it over the girl’s head to shatter against the wall. A piece of glass ricochets and strikes Tommy. A thin line of blood appears on his cheek. Startled, he stops crying and stares at her. A tear rolls from his eye and mixes with the blood. Ellie steps toward him. She wants to hug him and apologize. She aches from having hurt him. Her ex stops her and points toward the door, ordering her to leave. The girl has already scooped Tommy up, and he’s clinging to her, crying on the girl’s shoulder. Ellie tries again to reach him, but she’s pushed out the door. She’s never felt as alone and empty and sick inside as she does now, driving the highway that separates her old life from the void ahead. Her tears make the road shake and blur ahead of her, a watery mess of pavement and evergreens. She squeezes the wheel and pounds a fist into the ceiling with a series of unsatisfying thunks. She hates herself, hates being hostage to the tempest of her emotions. She swore she’d never fight in front of her son, never let him witness what a lousy bitch she was. She keeps picturing him, crying with the blood on his face. He’s afraid of her. She knows she’ll hurt him again and next time it will be worse. She can’t bear the thought. She wishes he could have another mother, somebody stable. The sky is growing dark and the cars have turned on their headlights—bright, accusing eyes coming at Crab Orchard Review

u 7

Troy D. Ehlers her and blazing past. The lights are mesmerizing, haloed in her teary vision, and her fingers loosen on the wheel and her foot becomes heavy on the gas. She imagines how easy it would be to veer into the lights, meet them head on and force them to pass their final judgment on her. But she won’t do it. She won’t hurt anybody else. Not ever again. She takes a breath and cranks the steering wheel. She flies over a narrow strip of grass and drives into a giant maple tree. A flash of violence and pain, shrieking steel and breaking glass, and it is over. With a stiff neck and crushing hangover, I awoke on the couch. It was the middle of the night. My back and stomach itched like a stiff wool sweater. I scratched my stomach and my fingers came away wet with blood. During my fitful dreams, I’d been rolling in the glass. On tiptoes, I made the bathroom without cutting my feet. The scratches were superficial, but blood splotched my skin and clothes. I looked like I’d been in a street fight. I took some aspirin and considered cleaning up the glass. Instead I wandered into the bedroom closet, retrieved the shoebox holding my recent photos and keepsakes, and spread them out on the kitchen table. During the peak of our relationship, Ellie had a camera strapped to her wrist at all times—as if she’d been desperate to preserve every moment together; as if she’d known anything that good couldn’t last forever. Despite my grief, it was impossible not to smile. She loved goofing around for the camera. Without warning, she’d hold it off at arm’s length and snap a shot of herself sticking her tongue in my ear or, while I was smiling for the lens, she’d secretly be stretching her mouth into a look of horror or cross her eyes and stick her tongue out to the side. Then I’d catch her and confiscate the camera. She’d clown around and model for me. Each time I snapped the shutter, there was another look on her face, a different expression, a different pose—always beautiful and ever-changing, never the frozen, meaningless smile most people wear on film. Flipping through the images was like reliving her myriad personalities: a mischievous grin, a brow-furrowed pout, a suggestive smile, an angry middle finger, a side-stitching laugh, a graceful (and somehow lonely) contemplation of the sky. Her emotional instability frightened me. It thrilled me. This was a woman I would never grow bored with. I could still be breathless from laughing at her zaniness when she’d say something profound and thoughtful, or draw me into an argument, or be crying on my 8 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers shoulder. I was enjoying things I hadn’t in years—biking, swimming, skating, skiing, going to rock concerts, food fights, games. It was like being a kid again. Ellie was my fountain of youth. Not long after Venezuela, she got divorced; I made her promise I wasn’t the reason. I didn’t want to break up a family and wondered whether we should go on. We took turns visiting one another—a three hour drive separated us. At first it was weekends (she didn’t have custody yet), then extended visits, and eventually a vacation: in the dead cold of January we flew to Grand Cayman. We rented a glass-bottom boat and picnicked in the harbor. Fish swam up beneath us and moved in their mysteriously synchronized schools, as if governed by a single mind. Ellie was silent for a time and then she said, “Why are you here?” I swallowed my sandwich. “What do you mean?” “You can’t really love me.” I put a hand on her knee. “Of course I love you.” She slapped my hand away. “Don’t patronize me.” “I wasn’t, I just—” “You don’t know me. Can’t you see what I am? I left my husband. I left my son. I have no friends. Nobody has any reason to feel anything toward me but hate. Tell me why you love me. Tell me.” “I have fun when I’m with you,” I said. “You make me laugh.” “Yeah, I’m funny.” Her face wrinkled in disgust. I took a breath. I wanted to brush the hair back from her forehead, but it would only make her angry. “You’re beautiful, Ellie. And I’m a different person when I’m with you. I do things I would never do on my own.” “I’ll bet you do.” She stared off across the water, her lip trembling. “Nobody sees me for who I am. Nobody cares.” “I care.” “Take me back to the hotel, Michael. I need a drink.” I began to realize the barrier between us. We could talk and laugh. We could argue and cry, play together and have sex. Ellie lived exclusively for me. Her life revolved around mine. The bond was constant and compelling. But it didn’t reach into the heart of us. This was codependency. In Grand Cayman I finally accepted that. A significant piece of her soul seemed buried in a fathomless trench. No matter how much we shared, she remained just beyond my fingertips. I fought like mad, straining against the currents to reach her, but we drifted apart. Crab Orchard Review

u 9

Troy D. Ehlers Sitting at my kitchen table, I picked up the photo of her on the beach, all but her laughing face buried in sand. A knot formed in my throat. The symbolism was too keen. It cut me. Had I given up too easily? Had she been there all along, buried beneath a mere dusting of sand? Maybe she only needed somebody to make an honest effort at digging her out. I needed another chance. I wanted to go back. If only I could return to that day, that month. I could have shown her I cared. If I had a second chance, I would be relentless. I wouldn’t stop until she accepted my love. She wouldn’t need to die, if only she believed. Ellie is tired. She feels aged beyond her years. Her arms are heavy and her joints swollen, decrepit. Her head is pressurized, throbbing from the inside as she lets it loll back on the top of her couch. The migraine has brought the auras again—yellow and red shadows glimmering about the room like ghosts. In a better mood, she’d talk to them. Tell them jokes laced with black humor. But she doesn’t have the energy. Today she will die. This is not an impulse. This is not a rash decision made in anger or desperation. She has been gradually worn away, like a stone beneath a waterfall. Amazing she’s lasted this long. She has served her purpose in this life. There is nothing more for her. Only pain. Slowly she gets to her feet. The exertion causes her migraine to flare. She stands still and breathes deeply, slowly, until it abates. Delicately, she walks to her bedroom. Everything is ready for her. She has tied a noose with her bed sheets. It hangs from her ceiling fan. She thought of using bed sheets because of a conversation we’d had. She told me she’d attempted suicide and I admitted that I had once, too. As a child. “I tried to hang myself with a bed sheet,” I said, “but the knot slipped.” Without thinking, she replied, “That’s too bad.” We’d laughed madly until tears ran down our cheeks. Ellie steps up onto her bed and looks through the noose. She has spent some time braiding the sheets. She’s reinforced them with rope. This knot will hold. There is no other way for her to die. She will die as the man she loves had once nearly died. She wants to share this with him. She wants to feel what he felt and taste the death that managed to elude him. She knows he will hear about it. It might hurt him. It might anger him. It might make him wish he’d held on to her. Or maybe, remembering the moment they’d shared, it would make him laugh. Somehow this death will affect him. That is all that matters. She steadies herself on the edge of the bed and slips the noose around her neck, slides it tight and fast. She fastens her hands behind her back 10 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers with handcuffs—handcuffs they’d used in lovemaking. She steps from the mattress and her body swings down. For a moment she worries her feet will graze the floor, but they don’t. Her throat is crushed and she cannot breathe. The last pulses surge harder into her brain and her migraine explodes, sending jets of light across her vision. She feels a horrible pressure in her skull and everything turns red. She thinks of the man she loves. She imagines the grief he’ll feel and she’s overcome with embarrassment and sorrow. She wants to stop this, undo it. She wants to spare him the pain. She kicks her feet toward the bed, tries to hook her toes on the edge of it. She tries to flex her neck, to hold herself up. The handcuffs are too tight. She kicks and struggles, but even despite the desperation, it seems she is falling asleep. She wants to wake up and free herself. She wants to wake up. She wants. The rest of that night passed in a haze and at some point I fell asleep, hunched over the kitchen table. When morning came, I felt restless, desperate to do something, anything. I didn’t have the energy. I sat on the floor in my guest bedroom and sorted through an old box of hockey cards I’d long forgotten. It was imperative I put them in numerical order. Things all over my house needed to be organized: books alphabetized, records categorized, videotapes labeled. I made a list of things that needed doing. Early afternoon, the doorbell rang. I cracked the door and peeked outside. Delinda stood clutching her handbag to her chest. “What’s the matter with you?” she said. “What?” “Your phone isn’t working.” “Oh, yeah,” I said, opening the door. “Sorry.” “Oh my god, what happened?” she yelled. I’d forgotten I was still wearing the blood-stained clothes. “It’s nothing. Don’t worry.” She stepped inside and lifted my shirt. “We need to get you cleaned up.” She grabbed my wrist and pulled me up the stairs like a child. I followed her to the bathroom. “Do you have hydrogen peroxide?” “They’re not going to get infected. It’s all scabbed over already.” “Well, get in the shower at least. I’ll find some clean clothes.” “I don’t need a shower. I’m fine.” She stepped around me and turned on the shower. “I’ll set clothes on the counter. Get in. You’ll feel better.” She left me to undress. She was wrong about it feeling better. The Crab Orchard Review

u 11

Troy D. Ehlers soap and water stung on the cuts. Some of them started bleeding again. I felt sick watching the pink water spiral down the drain. After the shower, I got dressed in the sweats Delinda had put out for me. I found her in the living room, putting glass in a garbage bag. “I gotta hand it to you, Mike. You didn’t miss an inch. You were very thorough.” Slivers of glass sparkled in the fireplace mortar. I was ashamed, watching her clean up after me. I dropped down on the step leading to the kitchen. Delinda sat down and squeezed me to her side. “We’re going to get through this.” She held me for a while. It was comforting. Nevertheless, it became impossible not to cry. She insisted on making lunch. She left me to rest in the kitchen while she finished cleaning up the glass with a vacuum. We talked until Delinda was convinced I’d be alright. She needed to bring her husband to the airport and watch her eighteen-month-old daughter, Callie. She wanted me to come with, told me I’d enjoy seeing Callie play—she was running around and getting into all kinds of mischief— but I was too tired. I promised to call later. Once she left, I tried returning to organizing, but I lacked motivation. I felt feverish and empty. There was no sorrow, no anger, and no pain. I had no thoughts or memories of Ellie. I felt nothing at all. The closest thing I had to an impulse or clear thought was the vague desire to just lie there, and do nothing. I turned on the stereo and closed my eyes. I remembered the pink water spiraling down the drain during my shower, the blood weeping up from the slashes in my skin. The horror and emptiness made me sick with vertigo. I saw a vase of roses. The petals crumpled and dropped into the water, dying it crimson. I saw wine, spilling over the lip of her glass, staining the carpet. I saw Ellie’s arms, floating on the pink darkening water. Her body is trembling from the cold. Water drips from the leaky faucet. The tiles are cold and hard against her neck. Sunlight grates through the Venetian blinds and illuminates the dust. A fly buzzes and thuds against the window. Outside, a truck rumbles past and children shout in the neighbor’s yard. She lies there feeling nothing from her floating body. The water has absorbed all sensation, even the pull of gravity. She is vaguely aware that this is her last chance to experience some emotion; she should feel anguish or sorrow, hatred or relief. She should be overwhelmed with loss. She feels nothing but emptiness.

12 u Crab Orchard Review

Troy D. Ehlers Nearly the entire Venezuelan group attended the funeral. Delinda greeted me with a long hug and kissed my cheek. Her husband shook my hand and, from his other arm, Callie reached out for me. I held Callie for a few minutes and Delinda had her repeat my name: “Unca Mite.” I laughed and my eyes teared up. When Cindy spotted me, she threw her arms around me, which was uncharacteristic. She whispered into my ear. She was sorry for saying those horrible things about Ellie. She was sorry for not thinking of my feelings. I told her there was nothing to apologize for. People shouldn’t be held accountable for what they do in grief. Ellie’s son stood there in a tiny black suit, holding his father’s hand. They were surrounded by family. I was thankful for not having to speak to them. Nothing I could’ve said would have mattered. With dear friends surrounding me, I caught only glimpses of the open casket. Ellie looked beautiful, radiant with peace. The graceful ease of her face lifted a burden from my heart and my breath became lighter. uuu

Ellie steps outside and feels the warmth of sunlight on her skin. A light breeze moves the hair on her forehead as she walks down the driveway. She tucks her hair behind her ears and pauses near the flowerbed. She kneels on the lawn and rakes some dried leaves from between the daisies with her fingers. New buds are spearing up from the soil, late for the season. She bends to smell the flowers and the green scent of the junipers. Children laugh in the distance. She turns up her face, and beneath this brilliant sun, this pale blue sky, she marvels at how much, how overwhelmingly much there is to love.

Crab Orchard Review

u 13

Dan Albergotti Holy Night My father said he wished the child were dead. He didn’t say it in so many words, but he said it. And it was Christmas Eve. I breathed in silent tension next to him. The news anchor said that of the seven born to a black couple three nights before the weakest child had gathered strength and would, the doctors said, most likely now survive. I’m sorry to hear that, my father hissed. That’s just what this country needs, seven more— of course he used the word. You know he did. The television screen blurred to pastels. I sat in silence next to him, the man whose blood was my blood, whose eyes looked like mine, and tried to breathe the thick air between us. He was my father. This was Christmas Eve. Lord of this other world, what will you make of this? And reader, what will you accept? That I stood up without a word and left the house, got into my car, and then drove to the pizza place as he expected me to, picked up our order, and drove back to that goddamned house to join my mother and sister, who’d been singing Christmas hymns

14 u Crab Orchard Review

Dan Albergotti by candlelight at the evening service while my father wished death upon a child? Will you accept that I wept on that drive, listening to Radiohead’s “The Tourist,” wishing I could stop the world’s spinning cold, drive off its surface and take to the sky, break its gravitational hold, sever myself from it forever then and there? Reader, I hear your silence now, hear it like I heard silence that night in the space between my father’s words and the night sky I could see through my windshield, one bright star— impossibly distant, already dead— pulsing its pure light through millennia of utter void to meet my aching eyes. Maybe it’s better that you have no words, that I have no answer. Maybe better to just recall the peace of that short drive, its brief respite where music and silence were one blessing and the dark night holy.

Crab Orchard Review

u 15

Lauren K. Alleyne How to Watch Your Son Die

for Miss Linda

When the grief comes, you monster through it. —Rachel McKibbens Watch his skin become a coffin for his breath. Watch his bones rise like phantoms to haunt the twilight of his flesh. Beneath the bedsheets of his lids, see his eyes twitch, blind and wandering; if opened, they are the most beautiful glass. He will unremember time and laughter. His name will become a strange music in the foreign instrument of your voice. Watch him lose each human border— his tongue forsaking language, his hands growing indifferent to reach or touch, his heart sputtering

16 u Crab Orchard Review

Lauren K. Alleyne its final messages to yours. Watch as he breaks from himself and becomes a body so quietly your tears thunder against his cheek.

Crab Orchard Review

u 17

Lauren K. Alleyne

Killed Boy, Beautiful World

for Aaron Campbell

How slender the tether between life and not-life, between the big-eyed boy of your childhood play, and the call that tells you he is lying beneath a sheet waiting to become ash. How ruthless with beauty the world seems, clouds tumbling in streams of white, the sky dappled, then clear, then blotted with rain; the news of death and more death streaming—some familiar or foreign blood damning every wet curve of the globe. Still, you want to hold on to it, this life that breaks you again and again. You want to know that poised as the world is to drive you to your knees with anguish or ecstasy, you are in it to stay as long as it will have you— as long as you have anything left to lose.

18 u Crab Orchard Review

Traci Brimhall In My Third Trimester, I Dream My Own Death In week twenty-seven, I dream a conquistador confronts me with unsigned Requerimientos. I’d give up any god to save a life, so I sign them all with a narwhal tooth dipped in squid ink. Oracular tremblings come in week thirty, waking in warm sweats after a holy fool who speaks only in vowels warns I will resort to prayer. A thief prophesies through week thirty-three—Resurrection is not ascendance, he cries. It is the spirit rejecting heaven for flesh. His body shines with the cruel radiance of a man who buried himself alive and returned to laugh, dance, pick cupuaçu. Jubilate. Week forty I spy rogue angels, jealous of their god’s fertile will, impregnating virgin orchids in the rainforest. They promise to trade the ecstasies of the anther cap for my first-born daughter and, before I can say no, I wake to my water broken, my dreams crawling out of the river, maculate and toothed, insisting, Even before you imagined us, we knew you.

Crab Orchard Review

u 19

Brian Brodeur Blight I was born in a city with a river running beneath it. Summers, the chemical stink of textile dyes seeped up from viaducts under the streets. Two bridges spanned a lake to the northeast that fed into the river underground. We heard of those who walked the bridges at night and climbed guardrails, scaling the trestles to leap into the water, disappearing. We heard a lot of things: the newborn boy dumped in a Papa Gino’s ladies room, the ServiceMaster van with painted windows parked by the playground woods, two teenage girls found naked in a ditch near Great Brook Valley where we were told never to go at night. Bored, we’d steal fresh cemetery flowers, and pitch them at each other, shattering blooms with a bat that gave us special power because we’d heard Yastrzemski owned it once. Sticky with strips of black electrical tape, it belonged to Joe Camuso down the street. When Joe showed up one day without the bat, he said his dad had split it beating a man he’d caught that morning pissing on their stoop. “Dad wasn’t even drunk,” Joe said, grinning. Police tape fluttered there until it tattered. The night Joe’s dad got off on self-defense, my own dad staggered home after the party at Stony’s Bar, waking my stepmother. I heard the thud of boots dropped on the floor,

20 u Crab Orchard Review

Brian Brodeur voices murmuring through the drywall. “I’m sick of all these Blacks,” he said. She shushed him: “Quiet, the kids will hear.” “Sorry,” he said, “I mean these African Americans.”

Crab Orchard Review

u 21

Catherine Champion Caliban, After Call it inheritance, that currency of moon, my mother’s temper that was never quite my own. And still I know nothing of what moves it all, what chicanery hides in the dive of fish, the tinny whir of beetles, and whether I remain my own, or subject to some chimerical constancy. I am tired of spells. Spells of books, spells of whiskey, of winds. But in solitude, I must atone for their phantoms, even though they are gone and not missed, because the night’s engulfment of sea is enough to make a child of anyone. I speak towards the aerial, asking for my mind, and what words the wind carries: Still, into the night the sky pulls the tide. Still, a ship’s eye, and no stone is settled. And in shatterable sleep you’ve unspun what is known—the sod before sea, your shiftable home

22 u Crab Orchard Review

Nandi Comer The Warning for Ai So many beautifully bloodied sounds tucked under my chin, breaking under pressurized note. I’ve made it through night working lines into a damp thigh, a stalled truck, a woman humming into her husband’s ear. Without occasion or motive, I’ve buried voices. I’ve studied the slow motion of carving breast meat. I shadow the butcher’s cut. I feel my face’s open grin when I sharpen my shears. The baritone of a bruised man’s chuckle rattles my lungs. A child’s star-like hand reaches across my belly. I have to yank them out. I had never heard wanting strapped to a boy’s wrists until I tied him down, made him sing. I’m a borrower of voice boxes, a surgeon of tongues. I am warning you: you ought to stop loving me; you ought not lay your story on my counter; you ought be careful before I take you up by your throat, before you find yourself barefoot in my kitchen, mute and panting.

Crab Orchard Review

u 23

Nandi Comer

Detroit, Llorona, My Heart, My City Another ripped night, another dank song, another bloated head of a headline child bobs in your river. Loaded barrel woman, pumped piston city, seven of your boys rushed a townhouse door for jewelry, for a cable box, for a game console, tossed over kitchen tables, turned another boy’s face to mush. And you? You’ve gone and gave up their ghosts. Singing a murderous sinfonietta you make another girl, another son dance on waves of your wails as if each bullet were a small celebration missile. I know this lost loveluck is not your fault. You do not mean to change a father’s body to canopy and shield, into a dead weight your daughter will tuck herself under until your singing is done, but I’ve watched you strained with moan and hymn. Your living room floor scattered with obituaried flaking faces. I’ve seen your organ arms’ frantic wave. The length of your fingers curved around carnation stems. Each night your skin twists mourn to mourn. Beating chest woman, yours is a solitary grief whose wailing provokes the next hand hooked

24 u Crab Orchard Review

Nandi Comer to an infant throat. Weeping woman, foolish mother. I’ve tried to sing your praise song, but each of your river-drowned children is a clanging cord in my throat. “Don’t stay,” you warn. You refuse to protect me. Still, I drag myself to you, kneel and kiss your oily asphalt knees. No one knows your grieving songs, our love of graveyard strolls. If only to fondle the fringes of small caskets, I come back. I retreat. I come back. I retreat.

Crab Orchard Review

u 25

Nandi Comer

Losing Between Manholes and Myths Here, girls keep ears tuned to heavy thunder, rippled sky, and cloudbursts—not to boys’ eyes following hemlines, nor catcalls from rooftops, nor a sweet shepherding palm at their waists. It’s the rains that dump women curbside, wet and cored. It’s never an unmarked taxi or stumbling through our stone town’s dark dawn. October is a constant downpour. Sidewalks overflow. Water whirlpools at every corner. Red awnings sag and drip. The storms in this town have already drowned many women. If a girl is not careful she gets pulled underground through an uncovered manhole. She won’t fall into a ditch, or come back with one broken limb. It’s not the dragging that swells their thin arms, not mouthfuls of gravel, not their tongues snipped off and jammed in mailboxes. A drizzle turns to thrill then threat. Knuckles washed translucent can’t endure the pull. I know what your newspapers say, but our men don’t turn their steering wheels down a dead-end street, they don’t stop in front of a house she doesn’t know. She will not need to kick

26 u Crab Orchard Review

Nandi Comer or scratch or plead that her father is willing to pay ten times he asks if she just makes it home. I’m telling you every southwest corner does not lead to a knot she can’t loosen, or a stained cloth she can’t spit up. Lower your window. Breathe the heavy humid air. Fear the streams of gutter water rivering through the town. Flood rain takes girls with muck and waste. The sewers make them bloated. It’s the storms that send their bodies crawling through piping towards a lake where all bobbing heads spring up.

Crab Orchard Review

u 27

Suzanne Hodsden Dead Boy’s Wedding The boy in the coffin was young, sixteen almost seventeen,

and wore a suit two sizes too big for him. A ring of pine boughs crowned his head and obstructed a clear view of his face. His family crowded at his feet, heads bowed and close together, leaning against one another for stability while a priest stood over his head and chanted the somber tenor notes of a funeral song that vibrated in the pre-dawn air. Everything else was quiet and still, and the scene’s only witness was Ruth Marfinescu, the American wife of Sorin Marfinescu, esteemed historian and archeologist. She was not wearing her glasses and thought the entire tableau some sort of great black beast with amoeba-like borders that undulated but never moved from its fixed space on the sidewalk beneath her apartment. It was an abomination sent from hell to terrorize her. The song had woken her and sent her to the window to see the source of the noise, swear at it, shame it to silence, and return to her bed to sleep however long she could before the church bells began their daily routine. This bell song would signal the start of the day and blast through the block of flats with an ear-splitting cacophony of song that would mark every subsequent hour throughout the day. There are three churches in Braşov within a mile of each other, and none of them agree on the time. The first two minutes of every daylight hour are filled with the arrhythmic clanging of bells. The Lutheran Church with its one large resonant bell started, and a few moments later, the atonal melody of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches joined in with their collection of smaller bells. After the last jarring chord, life would start. Old women would beat their rugs in the courtyard, and milkmen would push squeaky-wheeled carts past open windows, calling out and hoping to make a sale. The newly minted cellist next door liked to get an early start on his criminal ministrations to his instrument. The silence of the hours before the bells rang was a precious treasure that Ruth guarded with a religious fervor. Her knowledge of Romanian vulgarities was limited, but not

28 u Crab Orchard Review

Suzanne Hodsden preclusive. She retrieved her glasses, bent in half over her bedroom windowsill, and warmed up one of her favorite phrases of damnation, something about making skis out of an enemy’s broken femurs. She was about to let loose with it when she saw the singer, dressed head to toe in black, was most likely a priest. She was raised Baptist, and though she’d long since stopped talking to God with any regularity, a healthy fear of hell stopped her short of swearing at a man of the cloth. Then she saw the boy. She gripped the sides of the window and didn’t move until the bells began. Only then did she take a step back and slam the window shut, a primal instinct of self-preservation. Even through glass, the bells shook her by the bundle of nerves tied tight around the top of her spine and shattered against the hard bone of her skull. They rattled the thin walls of the soviet bloc-style apartment she shared with her husband. The apartment was fourteen by twenty-two feet, and, in the airless summer heat, the stench of two humans could be overwhelming if not properly ventilated. The window was only shut for seconds before she began to stifle, and she sagged under the weight of Romanian hospitality. She and her husband had visited his mother the night before, and rules dictated she accept whatever food or drink was offered to her lest she cause offense. More often than not, it was drink. Ruth couldn’t compete with people who’d been training their heads and livers for an entire lifetime, and Romanian social gatherings always addled her brains and good sense. So much so on that morning she’d been poised to scream at a funeral. She swallowed that ball of guilt whole, down into her gullet to mingle with the pickled contents of her stomach. Sorin was up and rooting around in the kitchen, and she walked the five feet to the foyer, if it could be called that. A four-by-five foot space contained three doors to three rooms: the bedroom, the kitchen, and the bathroom. Each room was smaller than the previous. Sorin was leaning out the window, observing the scene with a toothbrush in his mouth, nothing in his expression to suggest anything he saw on the ground was out of the ordinary. More surprising, given the direction of his eyebrows, was the fact his wife was out of bed. Her mother once told her anything she ever wanted to know about people could be worked out in the first hour of their day. Do they open a window? Wear slippers? When does coffee get involved? How many cups? Do they dress before breakfast? What paper do they read? The first hour is crucial because it’s rare for people to lie. It just doesn’t occur to them, her mother said. Give them an hour, and they Crab Orchard Review

u 29

Suzanne Hodsden are awake enough to know others are watching them. Sorin woke with the sun and was always well out of bed before Ruth opened her eyes. After nearly six months of marriage, she barely knew him at all. “There’s a dead person on the sidewalk,” she said. “Yes.” “Why?” “He must be buried.” She stood transfixed by the sight of her husband in his jockey shorts, stretching out the cricks in his back. If not for the silver in his hair and beard, his awkwardly thin body could be mistaken for an adolescent’s. They stood and stared at one another until the previous day’s argument woke up and put on its shoes; and when it did, his sigh of resignation sent the toothbrush swinging to the corner of his mouth. He pushed past her on a resolute path to the bathroom before she could speak. She cut around him and shut the bathroom door behind her. Usually Sorin respected his strange American wife’s insistence upon using the toilet in solitude, but he hesitated only a moment before he pushed the door open and scraped her knees in the process. He spit into the sink. The mix of toothpaste and silver in his hair made him look rabid. His head bent to rinse his mouth, and he met her glare for glare. If the yelling was to continue, he apparently wanted to do so without toothpaste in his mouth. The tub was filled with pillows and thick wool blankets. On nights they went to bed without speaking, Sorin packed the bathtub full of pillows and slept with his head against the soap dish. He made a show out of stretching out his back, throwing a glance into the tub with his makeshift bed and then back at her while he dried his hands on the towel, one finger at a time. “What is wrong?” he asked. “I’d like to pee in peace, that’s what’s fucking wrong.” “Hug my ass.” “Kiss. Kiss your ass. That’s the phrase, Sorin.” “You can do that, too, if you’d like.” He leaned against the sink and crossed his arms over his chest. “Who died?” His expression sobered. He left the bathroom and shut the door to let her finish. Through the crack, he told her their neighbors on the first floor had lost their oldest boy. “Alex?” She’d given Alex one or two English lessons in exchange for his wealth of Romanian vulgarities. Sorin didn’t answer. 30 u Crab Orchard Review

Suzanne Hodsden She walked out of the bathroom on knees that wobbled, made her way to the kitchen, and looked out the window. She could see him now and the abundance of greenery that pillowed and haloed his head. “Why didn’t you tell me?” Her words were mostly air and barely achieved any sort of audible tone. Sorin rummaged in the fridge and removed some milk and fresh cheese. Poking into the bread box, he seemed discouraged by the makings of his breakfast. He spoke without looking at her. “You need anything from the store?” “Answer me.” She didn’t need an answer. She already knew why her husband hadn’t mentioned the death of a child. If he told her, she’d think about Jacob, and Sorin and Ruth did not discuss her son. Alex was not much older than Jacob had been when he died. She’d buried her son in a confirmation suit two sizes too small. The casket she’d bought him was too big, but her teacher’s salary hadn’t been able to afford a custom order. The coffin’s extra space was enough to accommodate Jacob’s soccer ball between his feet alongside a few contraband heavy metal CDs she’d found under his bed. She’d placed a worn copy of Trumpet of the Swan under his right arm. The book had been gathering dust on his bedside table, waiting for him to be through with the boy wizard. Ruth looked down at the funeral gathering and searched faces for the mother but couldn’t distinguish her from the rest. All their faces were downturned and shrouded in clean white handkerchiefs. She struggled to recall the woman’s facial features or hair color. Though she’d passed her in the stairwell countless times, she couldn’t remember the woman’s face. She thought to herself that if God had any mercy in His heart, He’d have taken her, too. A woman in the block opposite appeared in her window with a small rug. She shook it with so much vigor it snapped. She showed no concern for the display below her. It was a day like any other, and there was work to be done. Passersby were completely disinterested. The boy’s death was just a fact of existence amongst a swirl of life: clotheslines of wet underpants, the reluctant ignition of car engines, and small children racing to reach the school on time. The mountains that framed the small valley city of Brașov looked on from the distance unmoved. Ruth steadied herself against the window. She wanted to shout at them, to tell them to stop and pay attention, or to at least be quiet, for god’s sake. “They should stop,” she said. “It’s like they don’t see him. Why don’t they see him?” Crab Orchard Review

u 31

Suzanne Hodsden Sorin put his hands on her shoulders, a light touch that asked permission. When she didn’t flinch or pull away, he let them rest there. “Are you all right?” She cleared her throat. “Why is there pine in the casket?” “It’s for his wedding,” said Sorin, as if that explained it. The flies outside began to buzz. The sun made them greedy, and she wasn’t sure she wanted breakfast at all. She went to the sink and poured herself a glass of water. “Wedding?” “It’s a Dacian thing, a pagan custom from before the Romans,” he said. He disappeared into the bedroom to dress. She followed him there, using both unreliable hands to hold her water glass. She waited for him to continue, but he was busy pulling on a pair of black pants and a T-shirt. “Look,” he said when fully dressed. “If we had been married here, there would have been pine at our wedding. If I was not married, and I died tomorrow, I would marry the dead. They would put pine with me to take to my wedding.” He pushed his keys into his pocket and hooked his wallet onto a chain on his belt loop. “Any one dead person in particular?” she asked. “I don’t know.” He shrugged. “I do know that no one in Romania gets out of marriage.” This last bit he said mostly to himself. Ruth finished her water and put the glass on the bedside coffee table. Sorin waved his arms about, dismissing her and any more questions she might ask. “It’s tradition.” For all his status as a scholar of history, there were certain things Sorin believed should be accepted without questions. He was halfway out of the apartment and called over his shoulder. “You sure you don’t want anything?” She nodded. When the door had shut behind him, she went into the kitchen to make coffee. She boiled enough water for two and sat at the chair closest to the window to observe the scene. One of the mourners wrapped his arms around the woman standing next to him. The woman pushed him away. Ruth had been in London for a conference, a year after sickness claimed her son and left her a childless single mother. Sorin had approached her sitting alone in a hotel bar. He asked why she was by herself, and she answered that she didn’t like being with people anymore. She warned him away. “I have a sad history,” she said. He sat down anyway. “Everyone in my country has a sad history,” 32 u Crab Orchard Review

Suzanne Hodsden he said, in reference to dictators, secret police, and national starvation. He reached out and pushed up one corner of her mouth. “But we smile anyway. When we can’t smile, we drink.” He said it so seriously that she laughed. “Oh, you shouldn’t do that,” he said. “I’ll fall in love with you.” She married him not long after because she didn’t want to go home. In a way, Ruth had fallen in love with Romania before Sorin. In America, her sadness infected everyone around her—her family, her students. In Romania, a bit more didn’t seem to make much of a difference. Her husband appeared on the sidewalk below and negotiated past the people crowding his path to the corner shop. His phone rang and he answered it, speaking loud enough for her to hear that he spoke in English. He confirmed his plans to attend a party at the museum that night. He said he didn’t know if his wife would attend or not. She watched him disappear around the corner. She dug through dressers and put on everything she had that was black. She tied her unruly hair up into the neatest knot she could manage and ran down the stairs of the building. She would stand sentinel even if no one else would, but looking down at Alex, she couldn’t see anything but Jacob. The priest covered the casket with a lid carved with roses, a cross, and concentric circles. The water she’d drunk welled up in the back of her throat. In the courtyard, a large white conversion van backed its way down the sidewalk and stopped in front of the funeral. Two men jumped out, came around, and opened the back doors. One was smoking a cigarette, and she hissed at him. “Put that out,” she said, and he returned her request with a blank stare. She rephrased her words into Romanian, saying something that amounted to “Extinguish your cigarette, man who has had sex with goats.” The priest looked up at her and shook his head. The mourners shuffled their feet toward the van and ushered the coffin inside. She sat down on the steps against the steel railing and closed her eyes. The van started and drove away, leaving a cloud of exhaust. Though she knew the funeral had left, the smell of the pine clung to her nostrils. The bells signaled the start of the next hour, and she cupped her hands over her ears to drown them out. When she opened her eyes again, Sorin stood in front of her, holding a plastic bag full of eggs. He fried enough eggs for them to share and put some yogurt into the mix as a treat. He ate with a determined gusto and asked what she had planned for the day. Crab Orchard Review

u 33

Suzanne Hodsden “Do you have Romanian lesson today?” he asked. “Do you teach?” She’d picked up a few classes on American customs and traditions at the University of Transylvania located downtown. She wasn’t listening to him. “Trumpet of the Swan,” she said. She was disappointed in her choice. Why not A Farewell to Arms, To Kill a Mockingbird, or maybe Catcher in the Rye? She’d chosen a child’s book instead of something that would teach him how to be a man. “Trumpet of the what?” She started at his voice. “Swan.” She held her hands out in an approximation of the bird’s size. “Large white bird. Long thin neck.” “Ah,” he said. “lebădă. Da. I know this bird.” “It’s a book,” she said. “About a swan that can’t make any noise so his father steals him a trumpet. It’s a book for children.” She shook her head and dismissed the topic. “Have you a copy?” he asked. In order to improve his English, Sorin had been systematically reading every book she owned. In a way, he was reading her. Peeling back the layers of her, one page at a time. “Not anymore,” she said, and returned to her breakfast. “Do you want to talk about Jacob?” He waited. “Ruth?” She looked up. “You have egg on your face,” she said. She was about to explain that she meant literally rather than figuratively and stopped herself. She reached across the table and brushed the food off the corner of his mouth. “You shouldn’t eat so fast.” “What-eh-ver,” he said. He’d learned that particular American expression of the dismissive from her, and the way he said it—complete with requisite hand wave—sounded like a young girl from California. She kept the information to herself and began to eat, a smile turning her mouth up at one corner. Their neighbor drew his bow across his miserable stringed monster and started the first few chords of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1, each note a grunt and a groan—a squeaky cry of despair from a beautiful instrument that deserved better. “Oh, God,” she said. She clenched her teeth and dropped her fork. Sorin got up and banged on the wall. He yelled something about the neighbor’s ass and lightning bolts that she didn’t fully understand. The museum where Sorin worked was hosting a party in honor of its new exhibition of Roman artifacts, and the bells had rung sixteen more times before Sorin finally convinced his wife to attend. Patrick 34 u Crab Orchard Review