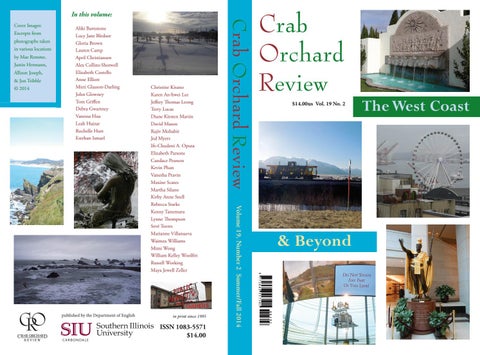

Cover Images: Excerpts from photographs taken in various locations by Mae Remme, Justin Hermann, Allison Joseph, & Jon Tribble © 2014

•

REVIEW

ISSN 1083-5571 $14.00

$14.00us Vol. 19 No. 2

& Beyond

00192

•

in print since 1995

Crab Orchard Review

9 771083 557101

CR AB ORCH AR D

published by the Department of English

Christine Kitano Karen An-hwei Lee Jeffrey Thomas Leong Terry Lucas Diane Kirsten Martin David Mason Rajiv Mohabir Jed Myers Ife-Chudeni A. Oputa Elizabeth Parsons Candace Pearson Kevin Phan Vanesha Pravin Maxine Scates Martha Silano Kirby Anne Snell Rebecca Starks Kenny Tanemura Lynne Thompson Sevé Torres Marianne Villanueva Waimea Williams Mimi Wong William Kelley Woolfitt Russell Working Maya Jewell Zeller

Volume 19, Number 2 Summer/Fall 2014

CO R

Aliki Barnstone Lucy Jane Bledsoe Gloria Brown Lauren Camp April Christiansen Alex Collins-Shotwell Elizabeth Costello Anne Elliott Mirri Glasson-Darling John Glowney Tom Griffen Debra Gwartney Vanessa Hua Leah Huizar Rochelle Hurt Esteban Ismael

Crab Orchard Review

In this volume:

The West Coast

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A Journal of Creative Works

Vol. 19 No. 2

“Hidden everywhere, a myriad leather seed-cases lie in wait…” —“Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” Thomas Kinsella Editor & Poetry Editor Allison Joseph

Founding Editor Richard Peterson

Prose Editor Carolyn Alessio

Managing Editor Jon Tribble

Editorial Intern Desiree Young

Assistant Editors Emily Rose Cole Loren Elise Foster M. Brett Gaffney Austin Kodra Zach Macholz Philip Martin Alyssha Nelson Staci R. Schoenfeld

SIU Press Interns Austin Kodra Philip Martin Board of Advisors Ellen Gilchrist Charles Johnson Rodney Jones Thomas Kinsella Richard Russo

Summer/Fall 2014 ISSN 1083-5571

Special Projects Assistant Cole Bucciaglia

The Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Address all correspondence to:

Crab Orchard Review

Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901 Crab Orchard Review (ISSN 1083-5571) is published twice a year by the Department of English, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Subscription rates in the United States for individuals are $25 for one year, $40 for two years, $50 for three years; the foreign rate for individuals is $40 for one year. Subscription rates for institutions are $28 for one year, $56 for two years, and $84 for three years; the foreign rate for institutions is $48 for one year. Single issues are $12 (please include an additional $10 for international orders). Copies not received will be replaced without charge if notice of nonreceipt is given within four months of publication. Six weeks notice required for change of address. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Crab Orchard Review, Department of English, Faner Hall 2380 Mail Code 4503, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 1000 Faner Drive, Carbondale, Illinois 62901. Crab Orchard Review considers submissions from February through April, and August through October of each year. Please visit our website, CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu, for the latest guidelines, calls for submissions, and contest information. Most of our submissions are now through CrabOrchardReview.submittable.com, so please do not send submissions via postal mail unless you are certain we are open for postal submissions at that time. Crab Orchard Review accepts no responsibility for unsolicited submissions and will not enter into correspondence about their loss or delay. Copyright © 2014 Crab Orchard Review Permission to reprint materials from this journal remains the decision of the authors. We request Crab Orchard Review be credited with initial publication. The publication of Crab Orchard Review is made possible with support from the Chancellor, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Department of English of Southern Illinois University Carbondale; and through generous private and corporate donations. “Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois,” 27 June 2014, 3900 copies printed, order number 114043. Lines from Thomas Kinsella’s poem “Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” are reprinted from Thomas Kinsella: Poems 1956-1973 (North Carolina: Wake Forest University Press, 1979) and appear by permission of the author. Crab Orchard Review is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Visit Crab Orchard Review’s website:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

Crab Orchard Review and its staff wish to thank these supporters for their generous contributions, aid, expertise, and encouragement: Barb Martin, Karl Kageff, Amy J. Etcheson, Bridget Brown, Lynanne Page, Angela Moore-Swafford, Wayne Larsen, and Kristine Priddy of Southern Illinois University Press Heidi Estel, Patty Norris, Joyce Schemonia, and Kelly Spencer Abby Allen, Shaylin Carlton, Kevin Savoie, and Savannah Broadway Dr. K.K. Collins (chair), Pinckney Benedict, Beth Lordan, Judy Jordan, Scott Blackwood, and the rest of the faculty in the SIUC Department of English Division of Continuing Education SIU Alumni Association The Graduate School The College of Liberal Arts The OfďŹ ce of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost The Southern Illinois Writers Guild

Crab Orchard Review is supported, in part, by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency.

Crab Orchard Review wishes to express its special thanks to our generous Charter Members/Benefactors, Patrons, Donors, and Supporting Subscribers listed on the following page whose contributions make the publication of this journal possible. We invite new Benefactors ($500 or more), Patrons ($200), Donors ($100), and Supporting Subscribers ($50) to join us. Supporting Subscribers receive a one-year subscription; Donors receive a two-year subscription; Patrons receive a three-year subscription; and Benefactors receive a lifetime subscription. Address all contributions to:

Crab Orchard Review Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901

CHARTER MEMBERS*/BENEFACTORS Rodney Jones Richard Jurek Joseph A. Like Greg & Peggy Legan* Beth L. Mohlenbrock* Jane I. Montgomery* Ruth E. Oleson* Richard “Pete” Peterson Peggy Shumaker

Carolyn Alessio & Jeremy Manier Pinckney & Laura Benedict Edward Brunner & Jane Cogie* Linda L. Casebeer Dwayne Dickerson* Jack Dyer* Joan Ferrell* John Guyon* John M. Howell*

PATRONS Diann Blakely Robert E. Hayes Kent Haruf Chris Kelsey Jesse Lee Kercheval Lisa J. McClure

Anita Peterson Eugenie & Roger Robinson Nat Sobel Betty & Ray Tribble David & Laura Tribble Clarisse Zimra

DONORS Lorna Blake Chris Bullard Heidi Czerwiec Charles Fanning Jewell A. Friend John & Nancy Jackson Reamy Jansen Rob & Melissa Jensen Elisabeth & Jon Luther

Charlotte and Gabriel Manier Lee Newton William Notter Lisa Ortiz Ricardo Pau-Llosa Lucia Perillo Angela Rubin Hans H. Rudnick William E. Simeone

SUPPORTING SUBSCRIBERS Serge & Joan Alessio Joanna Christopher K.K. Collins Corrine Frisch John & Robin Haller Zdena Heller Karen Hunsaker Lee Lever

Charlotte McLeod Peggy & Albert Melone Nadia Reimer Lee Robinson Catherine Rudnick Peter Rutkoff Victoria Weisfeld

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

Summer/Fall 2014 Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble

Volume 19, Number 2 Editors’ Prologue: Where Are We Going, Where Have We Been?

1

Fiction Lucy Jane Bledsoe Alex Collins-Shotwell

The House on the Coast

18

Strike-Slip

25

Anne Elliott

The Pacific Madrona

53

Mirri Glasson-Darling

True North

66

Vanessa Hua Elizabeth Parsons

Accepted

88

Bend Over Backwards

101

Marianne Villanueva

Crackers

123

Mimi Wong Russell Working

Model Minority

135

The Day Job

157

Nonfiction Prose Debra Gwartney

Her Hair

185

Waimea Williams

Sacred Valley, Modern Times

215

Poetry Aliki Barnstone

In the Workshop

6

Gloria Brown

Laying Irrigation Pipe in the Fruit Orchard Before Dawn

8

Lauren Camp April Christiansen

Riding the Rope Swing on Billy Goat Hill

10

Kalakala The Great Seattle Fire, June 6, 1889

12 14

Elizabeth Costello

Twelve Twenty-One Twelve, Nevada City

16

John Glowney Map Making Protest Out on Turnigan Arm, Resurrection Bay The Whale Skeleton at Long Beach, Washington

35 37 39

Tom Griffen

Homer Stevedore

43

Leah Huizar

Hominy Santa Monica

45 47

Rochelle Hurt

from The Gold Letters [The evening before you left, I watched you] [Lydia, I wait for gold to spill over] [Another dream, your hands full of gold rocks] [I am still as the stones on the floor]

Esteban Ismael Christine Kitano

Bay Park

76

Lucky Come Hawai‘i

78

41

49 50 51 52

Karen An-hwei Lee

Horses of War, Horses of Hysteria Meditation on San Joaquin Hills Prayer for a Woman Named Xochitl

80 82 84

Jeffrey Thomas Leong

Browsing the Walls at the Angel Island Immigration Station, I Seek the Lost Tones of the Heungshan Dialect At the Makai Market Food Court

85

Terry Lucas

Contra Costa

108

Diane Kirsten Martin

Contiguous

113

David Mason

Through Her Lens Amaknak

115 116

Rajiv Mohabir

On the Occasion of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani’s Birthday Acridotheres tristis Rhincodon typus Indo-Queer Windward-Side

118 119 120 122

Jed Myers

Coho Run

146

Ife-Chudeni A. Oputa

Portrait of Memory with Drought

148

Candace Pearson

Outside Tehachapi Prison

150

Kevin Phan

Some Things Which Filled Us with a Sense of Loitering

152

Vanesha Pravin

Sleep, Wake, Sleep

154

Maxine Scates

Speed

155

Martha Silano

This Highway’s a Ribbon,

172

Kirby Anne Snell

Geography Lesson Island Funeral

174 176

86

Rebecca Starks

Examination of Mono Lake

178

Kenny Tanemura

Evacuation Day Great Depression

182 184

Lynne Thompson Red Jasper Shasta

201 202

SevĂŠ Torres

Papi Stands at the San Juan Airport The Blood Back Home Sonnet: Puerto Rican History

204 206 208

William Kelley Woolfitt

Internees at Manzanar, 1942 (iii) Paiute Woman at Manzanar, 1935

209 210

Maya Jewell Zeller

Another Dream for Jessica Margaux Magnolia

211 213

Contributors’ Notes

221

A Note on Our Cover The ten photographs on the cover are by Mae Remme, Justin Hermann, Allison Joseph, and Jon Tribble. The photographs are of locations in Alaska, California, Oregon, Washington D.C., and Washington State. Details about the photographs are available on Crab Orchard Review’s Facebook Page:

www.facebook.com/CrabOrchardReview

Announcements We would like to congratulate three of our recent contributors, Kristine S. Ervin, Jim Fairhall, and Corey Morris. Kritine S. Ervin’s nonfiction piece “Cleaving To” and Jim Fairhall’s nonfiction piece “Núi Khê Revisited,” which both appeared in Crab Orchard Review, Volume 17, Number 1 (Winter/Spring 2012), and Corey Morris’s nonfiction piece “Carp River,” which appeared in Crab Orchard Review, Volume 17, Number 2 (Summer/Fall 2012), our special issue, “Due North,” were all selected as Notable Essays of 2012 for The Best American Essays 2013, by series editor Robert Atwan.

The 2014 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction We are pleased to announce the winners of the 2014 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction. The winners were selected by the editors of Crab Orchard Review. In poetry, our winner is Terry Lucas of Mill Valley, California, for his poem “Contra Costa.” In fiction, the winner is Russell Working of Oak Park, Illinois, for his story “The Day Job.” And in literary nonfiction, the winner is Debra Gwartney of Finn Rock, Oregon, for her essay “Her Hair.” The winner in each genre category—Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction—is published in this issue and received a $2000.00 award. All entries were asked fit the topic of the Summer/Fall 2014 special issue, “The West Coast & Beyond,” focusing on writing exploring the people, places, history, and changes shaping these U.S. States, Commonwealths, and Territories: California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, the United States Virgin Islands, and other areas which have been a part of the United States beyond the Lower 48 States (excepting those States listed here). Visit us online. Crab Orchard Review’s website has information on subscriptions, calls for submissions and guidelines, contest information and results, and past, current, and future issues:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

The Winners of the 2014 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction

2014 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Poetry

“Contra Costa” by Terry Lucas (Mill Valley, California)

2014 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Fiction

“The Day Job” by Russell Working (Oak Park, Illinois)

2014 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Literary Nonfiction

“Her Hair” by Debra Gwartney (Finn Rock, Oregon)

CO R

CR AB ORCH AR D •

•

REVIEW

Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble

Editors’ Prologue: Where Are We Going, Where Have We Been? This publishing journey began five years ago in Illinois, or,

putting things more accurately, the journey began about Illinois. Crab Orchard Review would reach its fifteenth year of publication in 2010, but the year before was a very challenging time for our university, the state of Illinois, and the arts in general across the country as the effects of the economic downturn of the three preceding years had taken their toll on all levels of funding and fundraising. With an uncertain future ahead of the magazine, our editor-in-chief and poetry editor, Allison Joseph, decided that if 2009 could be the last year we would be able to put together an issue of Crab Orchard Review, then the magazine we would produce would be a tribute to the vitality of contemporary writing about and from the state of Illinois, and our special issue “Land of Lincoln” was conceived. Our prose editor, Carolyn Alessio, was born in the Chicago suburbs and lives in the city itself today, and she wrote in the “Editor’s Prologue” of the issue of two of Chicago’s literary giants, Carl Sandburg and Gwendolyn Brooks, and of the pull the state experiences to this day between the rural and urban visions that shape the people, the politics, and the land itself. She also examined the erasure of both city and country that takes place in the suburbs and wrote of the struggle to continue to preserve history where to fight against a “paved-over sense of place” demands digging beyond the surface of a story. There was great satisfaction in completing our issue “Land of Lincoln: Writing about and from Illinois,” and there was even greater relief as it became apparent that Crab Orchard Review would be able to plan for a future beyond our fifteenth year. The next place that captured our imagination was the American South. At this point, we were still thinking a year at a time in our planning, and the idea for a “Southern” issue was Allison’s Crab Orchard Review

u 1

Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble – Editors’ Prologue suggestion. She felt after the immersion in the Midwest that came with working on the “Land of Lincoln” issue that a trip down South would be intriguing and informative, and it would reflect Crab Orchard Review’s mission to publish diverse voices. Our idea of “Old & New: Re-Visions of the American South” brought us just that, and the range of explorations in the work we received and were able to publish refreshed many ideas about the South of the past and the present. Our managing editor, Jon Tribble, was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and grew up just outside the city only a few years after the unrest at Central High in 1957, when some of the worst of the hatred and cowardice and some of the best of the strength and courage of the South was on display. In his “Editor’s Prologue,” he wrote of this legacy and of the connections through family history to the Confederacy and the way suspicion and landscape and story are as inescapable today in the South as they have ever been. By the midway point of our editorial work on the “Southern” issue, we realized that if we were going to make it to our twentieth year then we only had three more special issues before we had to think about a twentieth-year special issue in 2015. So we considered the possibility of making our 2012, 2013, and 2014 special issues into a kind of anthology exploring the United States of America and its regions as subject. Of course, how those regions could be defined can be endlessly debated—New England, Mid-Atlantic, Appalachian Highlands, Southeast, Midwest, Heartland, Southwest, Mountain, Pacific Coast, Alaska, and Hawai‘i would be just one of many possibilities—and we had three remaining issues to work with for our “American” anthology. After some discussion, we decided the final three issues would encompass what we would title “the North” (roughly a counterpoint to the “South” of the Confederacy), “Prairies, Plains, Mountains, Deserts” (or what we would often refer to as “the Big Middle”), and, finally, “the West Coast & Beyond” (California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Hawai‘i, commonwealths, territories, and areas of U.S. occupation, if writers decided to explore those in their works). We knew these were not necessarily traditional regions, but we were curious how these divisions would present us with unexpected discoveries when published together.

2 u Crab Orchard Review

Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble – Editors’ Prologue The “North” presented us with some peculiar problems. It seemed early on in the process of receiving submissions for the “Due North” issue that everyone was defining “North” by the weather and we saw more snowy landscapes in poems, stories, and essays than the worst winter outside of the polar regions. The “North” was also predominantly being defined as purely rural, as if Detroit and Rochester and Cleveland and Milwaukee didn’t exist. To change this among the submissions, we put out specific calls asking for work about the many cities that exist across the region. We also found it helpful to call for submissions about three specific states—Delaware, Connecticut, and Rhode Island— when we realized that we were reading very few submissions which mentioned these states in any way. Our editor and poetry editor, Allison Joseph, explored the challenges that came with putting together the “Due North” issue in her “Editor’s Prologue.” She wrote, “Like many of the writers in this issue, I am a product of this undefined region,” and she went on to detail her particular experiences from growing up in the Bronx, New York, attending college in Gambier, Ohio, and her life in Carbondale, Illinois. As she wrote: Perhaps my personal story illustrates there is no “true North,” which is why this issue is titled “Due North” instead. We wanted to go beyond placid snowy New England landscapes to see what else writers had on their minds. The submissions for the “Prairies, Plains, Mountains, Deserts” issue did not surprise us when, at first, we found ourselves reading quite a bit about all four landscapes usually devoid of people and often in places which, if a particular location’s names or landmarks or flora or fauna were not included, could have been anywhere across the thousands and thousands of square miles of “the Big Middle.” There were two things that became very clear from the earliest subsmissions we read: the prairies and plains were lonely and the desert was dry (we’re still not sure why the mountains weren’t characterized in a similar way). But we had learned from our own editorial experiences on the previous “American” anthology issues and, by communicating with the writers about the diverse possibilities we hoped to see represented in the issue, the unique elements of the people, places, histories, and cultures Crab Orchard Review

u 3

Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble – Editors’ Prologue became a part of “Prairies, Plains, Mountains, Deserts” in ways beyond our hopes for the issue. Our managing editor, Jon Tribble, once again wrote the “Editor’s Prologue,” and his piece was an exploration of travel through the “flyover states.” But more importantly, the prologue was also a tribute to a dear friend of Crab Orchard Review, the poet, editor, teacher, and scholar Jake Adam York, who had died suddenly on December 16, 2012. The prologue closed with a poem of Jake’s, “Pilgrimage,” that was first published in our 2003 special issue “Taste the World: Writers on Food.” In its opening lines, “Pilgrimage” speaks to the spirit that brought us forward in the journey these issues have been taking us on, the wonder of discovery that for editors means we turn the next page and the next, knowing that with dedication and good fortune we will find something we didn’t exactly know we were looking for but hoped was there. As Jake Adam York wrote: Well off the map, on roads that branch like capillaries into the blanks, we follow the turns of rumor far beyond the interstate’s shoulders, the travel like prayer, so far gone from any place we know… So this brings us now to “The West Coast & Beyond,” our final issue in this “American” anthology that we have come to realize could go on for many more years and still not exhaust itself—just like any living national literature should. We are pleased to present the final edition in this series, an issue full of unique characters—both native to their places and relocated—; landscapes that are urban, suburban, rural, sublime, distressed, lived-in, and resistant; stories and images and music from moments of ending and beginning; and, most of all, a collection of authors bringing their visions of “the West Coast & Beyond” to life through their stories, poems, and essays. Though we did not set out to do so, the four issues that make up Crab Orchard Review’s 2011–2014 “American” anthology—Volume 16, Number 2, “Old & New: Re-Visions of the American South”; Volume 17, Number 2, “Due North”; Volume 18, Number 2, “Prairies, 4 u Crab Orchard Review

Allison Joseph and Jon Tribble – Editors’ Prologue Plains, Mountains, Deserts”; and Volume 19, Number 2, “The West Coast & Beyond”—include at least one story, poem, or essay about, or work by an author born in or living in every one of the fifty states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. We have always known there is a talented and diverse community of writers and materials to publish all across this country and we are very happy that our experience publishing these four issues further confirmed what we have known these last nineteen years with Crab Orchard Review.

Crab Orchard Review

u 5

Aliki Barnstone In the Workshop That was the September when Berkeley was still novel and I took photos of my new Earth: the crowd of us sprawled on the Plaza’s brick because there on the Mario Savio Steps Allen Ginsberg wore a long golden tie, played his harmonium on a plastic chair, and sang “Tyger, tyger burning bright.” A few chosen poets stood around the sage’s throne, each taking his turn, and our friend from the workshop read the poem we already knew was too beautiful and too lacerating, the tracks on their arms a map of shivers, the no-walls sex they’d have anyplace, their glorious climb to Inspiration Point at dawn— the sun orange enough to eat, uneaten oranges in their hands, unoffered in the temple heroin made of their bodies. Then their stroll downhill was more a free-fall or swan song over the Bay— how mesmerizing the waters’ surface where sun-glare whirled with fathomless blues all the way to the Golden Gate and anywhere they’d find to crash—a mat of redwood needles, some friends’ itchy mattress in the flatlands, cardboard laid on concrete below an underpass near the Marina. When he read aloud, I wanted the high to be metaphor—painlessness is a form of radiance, only words, not the body of the poet wasting away. And if underlying his lines we detected disease, we were helpless to address it. If I wanted, I’d remember what I called him clearly 6 u Crab Orchard Review

Aliki Barnstone as his attentive expression and thin body leaning in close as I read my poem—my forgetfulness won’t disturb his state— and if he heard his name he might turn back to Earth from the high place where the dead go.

Crab Orchard Review

u 7

Gloria Brown

Laying Irrigation Pipe in the Fruit Orchard Before Dawn When bent wings of birds quiver above nested chicks, farmhands bend to groaning, straining, labor. Lengths of steel pipe are lifted onto a battered flatbed trailer coupled to a restless tractor. Even shiver of darkness cannot prevent sweat from soaking cotton shirts that cling and clutch work-strong chests and backs. The idling tractor sputters, chuffs, and coughs its readiness to work. It lurches its burden forward and the men follow, forming a quiet processional in the gray incense of exhaust. Each man intones a silent prayer that his work will serve to quench the brown thirst of the fruit trees that march in mute symmetry toward the world’s barbed-wire edge. Between the ranks of trees, pipe is laid in deep furrows. Pastel light threatens to breech the lip of sentinel hills at attention on the eastern edge of the valley. The race is to finish this task in half-dark. Weathered hands marry one length of pipe to the next, until all are connected to the one source. And the farmer spins the wheel that spills the water 8 u Crab Orchard Review

Gloria Brown just as the sun spreads across the face of this day. Circling in a ceaseless loop, the seasons with their list of chores etch the epitaph deeper into the granite of the farmer’s life.

Crab Orchard Review

u 9

Lauren Camp Riding the Rope Swing on Billy Goat Hill We climb wood steps, slow our pace to fog spray, plunk down on ghosted planks while shadows spill and underfill around us. Light turns just enough to shrink and roll away. It is now or 20 years ago, the last time I saw him. At the top of the hill, he says my name so clearly it’s an invasion of privacy. I look down on the alabaster church sitting slack in the dander of light from our vantage point above tabulated hills. It is autumn, a sensible morning. He bunches his body into a rope slung from a vast eucalyptus, and combusts with fumble and need, a man who expects the earth to come towards him and who knows mending comes later if you fly fast enough. What he would have done back then, in youth, is what he did now: spin through rapture. The city rolled by: Diamond Heights to Glen Park and downtown. Did he see it, so fast? He landed, his feet flaking dry dirt, shirt torn at the elbow and ridges of spine —and smiled, the way that is both now, and the way I remembered. He rose in the rocks in the hill, with the plait of the rope still sort of around him. Hiking down, back to his house, he was slightly limp but not whining, and we knew 10 u Crab Orchard Review

Lauren Camp we were lucky to be under this generous sun, finally professing light to everyone. We knew the collision was ours. We were easing back on time, which had made us grownups, turned us around, when what we wanted was what we were, where we’d still go, who we might become.

Crab Orchard Review

u 11

April Christiansen Kalakala Beyond the sailboats a submarine-shaped hulk lurks. Rust streaks down to water. When it leaves I will fixate on its ghost: The Peralta, the second to last steamship built in San Francisco Bay, melted. Her steel hull was tugged up the coast. She should be more rounded. Warm evenings on the Sound, ladies dance to Joe Bowen on the flying bird, rest in the lounge as seagulls dip past portholes. Perched on a vibrating red stool at the double horseshoe cafĂŠ, a commuter forks sugar-cured ham and potatoes, buys coffee by the half cup. Towed further north, then beached, men secured her with rock and sand, removed her relics: a shrimp cannery, gutted, stagnant in the Land of the Midnight Sun.

12 u Crab Orchard Review

April Christiansen Then the ephemeral drift further back. Restored beyond the sailboats, the submarine-shaped hulk lurks: a figment, buried in the water.

Crab Orchard Review

u 13

April Christiansen

The Great Seattle Fire, June 6, 1889 Everything take fire. —John Back A fitful wind blew through the open windows as the cabinet makers above the paint shop cut box joints, chiseled oak. On the stove, an unwatched glue pot, a stream of black smoke. Shouts. Pitched water. The surface glazed, boiled over. Glue embers tumbled into shavings littering a turpentine-soaked floor, and men grabbed their coats, flew to the stairwell as flames fastened themselves to the building’s walls, inching towards the liquor warehouse next door. Glass shattered, the crisp smell of burnt alcohol and paint filled the sidewalks, and a crowd gathered. Hydrants fizzled out, and in the background, the ominous sound of the Opera House, crackling. Smoke darkened the firmament, thickened. Steamboats backed into the bay. In piano showrooms, ebony and ivory disjoined, spruce curled at the edges, and inside, hammers bent, steel wire snapped, re-shaped. On tracks, cable cars went ablaze. Men chucked burning sidewalk over cliffs, ripped up planking in the roadway, and blew up an entire city block, struck it with gunpowder to obstruct the fire, but blocks kept going, each lighting the next. Coffee houses, cigar shops,

14 u Crab Orchard Review

April Christiansen the Times building: a seething cellar of flame. Horses, wild, unmanageable with fear, raced up steep hills, trampled abandoned spokes and smoldering debris. Even the undertakers were at a loss, shuffling their costliest equipment into carts, racing the flames, leaving the already-dead embalmed in their cloth-covered caskets. Near the bucket brigade, the confectioner stuffed his pockets with gumballs, caramels, placed jars of jawbreakers, brittle, and licorice on the street, left trays of candy apples and fudge cooling on racks, to singe. Disoriented rats trapped on rafters never made it out, suffocated or crisped. By the time the fire reached the wharves, an artificial dusk bathed the sky. In the morning, among a mass of ashes, a list of survivors and where they might be found in the heat and dust. Then, before the embers cooled, the bricking in of the remains.

Crab Orchard Review

u 15

Elizabeth Costello Twelve Twenty-One Twelve, Nevada City Here are the shops of dresses like dresses of the past, less the corsets of whalebone. Romance is better than history, which tells us much too clearly that pyrite isn’t gold. Let’s rest our ribs against the lace, but trim away what itches. Let their suffering be our glamour— gathered bodice, crinoline, ruffles at the neck. Take that, starvation and pestilence. Our crocheted half-gloves transmit no ague, and our fingertips are free of filth. Let’s don the bonnets but forget to die in childbirth. Nevada City, let’s light the lamps and bank the fires. Twelve twenty-one twelve isn’t the last day, but at least the wind makes fists and boxes off the hot-tub’s lid, setting the twenty-first century steam against sleet like sleet that struck the miners’ faces chilling them and their women to the bone. At night they trimmed the wicks and

16 u Crab Orchard Review

Elizabeth Costello unbound their ribs, but could not unfix their fortunes. Fearing a boundless breath, hard-handed women wept.

Crab Orchard Review

u 17

Lucy Jane Bledsoe The House on the Coast One morning I woke up and realized that I could see the end

of my life. It wasn’t hard and fixed, like the crest of a cityscape, but rather it shimmered like a polar horizon. This view of the end was troubling, to say the least, but the shimmer was hope. I had a chance—for something—if I acted quickly. When I told this to a friend, who happened to be a therapist, she gave me a look, something between pity and mirth. “You could be hit by a car tomorrow,” she offered, and it did help, at least for a few days. But then I woke up again, another morning, and looked forward, straight ahead, and saw the days stacking up, the years like a tower of blocks, and me climbing that tower with agility and care, too much care. The goal was supposed to be to keep the tower from toppling. The urge was to kick the whole thing down. The confusing part was that the urge didn’t come from discontent. I liked my life. It was more a physics thing, the pent-up energy in that tower. Or maybe it was nothing more than gravity. Whatever the force, I found I couldn’t ignore it. “At least you didn’t wake up one morning and decide you’re a cockroach,” my therapist friend said. “I’m not the type to go mad,” I told her. “You know that.” My partner of eleven years assumed that there was someone else. Who wouldn’t? We hadn’t had sex in months. We’d even stopped fighting. We came home from work, smiled at each other, made food, went to meetings and read books, and drank wine. Lots of wine. I left. Not her. I didn’t mean to leave her. Not even our life. I left my life. But of course that included her, and our life, so to her it must have felt like I was leaving her. Since that would be unbearable, I did the deed surreptitiously. I packed a few things in a suitcase and rolled it out the door to my car while she was at work. I made it look as if I were going on a mere business trip. Look to whom, I couldn’t say, since the neighbors weren’t watching, or certainly didn’t care. I lifted the suitcase into my car and drove to the coast.

18 u Crab Orchard Review

Lucy Jane Bledsoe When I was fourteen years old, I made the same ninety-mile journey, from Portland to the ocean, on my bicycle. I almost lost my life on that adventure, several times, to speeding log trucks. I’ve taken other risks in my life. I’ve climbed mountains without the proper gear, ingested hallucinatory narcotics, gone home from bars with strangers. Never, though, had the risk felt so great as it did that morning driving away from our home, suitcase in the trunk, my cell phone left on the kitchen table so I wouldn’t be tempted to call or answer. As I slowed through the speed-trap town of Dundee, it occurred to me that she’d think I’d been in a car accident. She’d be calling the police and hospitals by nine o’clock tonight. Quickly, so I could make the call before she got home from work, I swerved off the highway and into a McDonald’s where I used the crusty pay phone on the outside of the building to call our home phone. I said that she shouldn’t worry, that I’d gone on a trip. I paused for way too long, not wanting to just hang up and yet not having a clue what else I could add. So I placed the handset on its holder and disconnected the call. Our friends would tell her I was cruel. The more thoughtful ones would ask if I’d shown signs of a breakdown. Maybe both were true. What I do know is that this leaving felt necessary. There were hawk’s wings in my chest, flapping hard. I had an overabundance of chi. I’d taken a curve too fast and couldn’t straighten out my course. When I got to a sign that said “Oregon Beaches,” I took the exit. My sinuses felt as if they were opening. I imagined singing when I saw the sea. I don’t know how I found the house. Blind driving. The same way I found my partner, I suppose, it’s just where I arrived. Getting into the house was easy. A sticker on the window next to the door claimed the existence of an alarm, but the house was isolated, on a cliff above the surf, and miles away from any police station. I would just drive away if the alarm threat panned out. I did pause here. The question why slid around in my mind like a bumper car on a slick track, its circuit pole sparking. But the question wouldn’t take hold, refused to join anything that resembled an answer, just bounced off, bounced off hard. Still, I’m a rational being, and I recognized my pending folly and the likely and terrible outcome. Pausing, though, was the best I could do. I walked to the edge of the patio and looked out at the ocean. The blue and white, the vast wetness, the salty breath, these all satisfied me immensely. I felt as if I could see most of the world from here, the Crab Orchard Review

u 19

Lucy Jane Bledsoe seventy percent that was water with its lovely trim of sand. This view allowed me to ignore that other thirty percent, the peopled one, the wars and waste. The door was locked. But the window over the kitchen sink pushed in easily. Hoisting myself up to its sill and then fitting my body through the opening was almost impossible. I landed with one foot in the kitchen sink, my crotch slung painfully on the sill, and without the leverage to finish the job. No alarm went off—which at that moment felt like my bad luck because how else was I going to be rescued? I lifted my head and saw the ocean, right there out the front window of the house, and launched myself toward the view. I was in, draped across the countertop and sliding to the floor, bruised but pleased with my accomplishment. That evening I warmed a can of soup and opened what turned out to be a very good bottle of wine. I felt guilty about the latter and noted the label so I could replace it. I slept better than I’d slept in weeks, maybe years, and in the morning I left the door unlocked and walked on the beach. There were lots of very old books in the house, leftovers from people’s childhoods, like Nancy Drews and Laura Ingalls Wilders. Over the course of the next three days, I read these and ate small healthy meals and walked on the beach each morning and evening. On the fourth morning, I awoke to slashing rain and, while I stuck to my schedule, I shortened my walks. Just before dusk, as I was getting ready to open a new bottle of wine, the front door opened. I recognized her from the photo albums. She was the only girl. I’d wondered what it had been like for her, growing up with four brothers. I knew one of them had gotten married in this house, that the parents were both still living, and that she rarely attended family events. Most of the pictures—the boys with their wives and children, the parents who were now grandparents—did not include her. “Oh!” she said without too much alarm. “I didn’t know the house was rented.” “Come in,” I said. “No problem.” She looked around quickly. “Well. No. Of course not. It’s just that usually, when the house is rented, it gets put on the online calendar.” “Please,” I said. I’d almost become lonely by then, and anyway, I liked her messy curls and the serious set of her mouth. “I was just about to have a glass of wine.” 20 u Crab Orchard Review

Lucy Jane Bledsoe She dropped her duffle and took a big breath. She had the appearance of running from something, but then maybe I was projecting. “Are you all right?” I asked. Her name, I knew from the albums, was Henrietta. I was glad I’d cleaned the house so thoroughly the day before. It’d needed it, and it was something I could give back. I’d also, after much searching and finally finding a boutique wine shop, replaced the fancy bottle I’d drunk with two more of the same. I sunk the spiral into the cork and began twisting the handle. Henrietta sat in one of the chairs in front of the window and looked out at the blackening rain. I handed her a glass and sat in the other chair. “I’m not renting the house,” I told her. “I broke in four days ago. I’ve just been staying here.” She stared at me. Then she cracked a small smile. She thought I was joking. “I’ll pack now and go. I haven’t taken anything. In fact, I’m leaving the house in better condition than I found it.” She glanced around, as if to check on the truth in my claim. She was beginning to believe me. “Who are you?” she asked. She really wanted to know, I could see that. I wished I could answer the question the way it’s supposed to be answered, with something clean and simple, like, “My name is Penelope Higgins, I live with my partner Angie Weinstein, and I work as a paralegal in Portland.” Instead, I could only think of shimmering horizons and toppling blocks. I wanted to give her a future answer, which was as preposterous as the impulse that sent me here to the coast in the first place. She had little patience for my stuttering attempt at an answer and she waved the question away, as if it had been rude of her to ask, and said, “Stay.” Then she dropped her face into her hands and began sobbing. I didn’t know her well enough to even pat her back, so I settled into my chair and watched the fat raindrops slosh down the long windows. It was completely dark by now and I couldn’t see out to the ocean, only the reflected images of two women, one doubled over and one sitting upright. I listened to her wet gulps. I even sipped my wine, not callously, just patiently. I envied her long cry. She straightened, blew her nose and wiped her face on the bottom of her T-shirt, bent one leg at the knee and tucked the foot under Crab Orchard Review

u 21

Lucy Jane Bledsoe herself, faced me, leaned her shoulder comfortably into the back of the chair, and said, “I was always the fuckup. Cs instead of As. Pregnant at fifteen. It wasn’t the morals they were angry about, it was the stupidity. Abortion. Pregnant again at nineteen. This time I married the guy, who left me a couple of months later without the grace of a divorce. A musician. Yeah, rock. They might have taken my side if he’d been classical, but no one expected anything of this guy from the get-go. Of course they were right. For all I know, he’s dead, never heard from him again and his band definitely did not ever see the light of day. But who cares, because marriage is not something I need to do again.” “You could still get a divorce—” She waved the thought away. “Yeah, sure, of course, I know. Why bother?” “Okay,” I said, a bit ridiculously, as if she cared about my validation. I cared, though, in an intensely spontaneous way, like my wanting to affirm her choices was a giant metal snap popping me into her narrative. Maybe she felt the connection because she delved on. “Once Emma was born, I didn’t need anything else. We were a complete world, all our own. At first I thought I was being the cruel one, keeping the grandparents from her. But then I became convinced they didn’t want to know her, were even afraid, like she was too raw for them. They had other grandchildren, smart ones who learned to read at three, their lives fitted out with all the trappings, and I do use that word purposefully. With us, it was just me and Emma. So I stayed away. We didn’t need anything else. I knew they wouldn’t understand that, and I pitied them their lives so full of stuff. My brothers made partner, got fellowships and promotions, accumulated wealth, sold paintings. Even the gay artist one has made it. “We were fine, me and Emma. I couldn’t explain that to them. They’d never believe it, me with my library shelving jobs and periods of unemployment. Me cashing the checks they sent, which I only did because of Emma. I never would have, if it were only me.” Henrietta unzipped a hard, inscrutable smile and looked behind us, at the worn orange rug. “Twenty-one years ago today, Emma was conceived, right there, on the floor, on this very rug.” I thought she was going to get up and walk to the spot, maybe lie down in it, but instead she shifted in the chair, faced forward with her elbows on her knees and chin in her hands. Henrietta’s body seemed to plump with a briny liquid. “She died when she was three.” 22 u Crab Orchard Review

Lucy Jane Bledsoe In the long silence I wanted to ask, of what? The urge to garble anything into that void was so great. I don’t know how I managed to curb myself. Of what. As if that mattered even a little bit next to the absence of this woman’s little girl. “They all tried,” she said after awhile. “Every single one of them. My father. My mother. All four brothers. They came to our apartment for the first time. They sat with me. They sent more money. But all I could feel was that Emma and I weren’t as valuable, that she wasn’t as great a loss, as anything they could ever lose. I didn’t think they could conceive of the love she and I shared.” After a brief pause, she said, “I’m forty now. How old are you?” “Just a couple of years older.” She nodded. “I’ve decided to come home. Like, capital H. But I don’t know what that means. Dinner with Mom and Dad? An apartment in Portland? Does it mean forgiveness? And who of whom? So I’m starting here. This house is my earliest memory of love. Reading for hours on rainy days. Finding sand dollars and agates on the beach. They had so much hope for me.” She sat in silence for a long time, and again I didn’t speak either. “I’ve had men,” she eventually continued. “One or two who loved me, and one who I loved back. But it was never enough. Losing Emma…she was three…is a gulf that can never be crossed. “I’m still promiscuous.” She savored, took refuge in the word. “I like to fuck.” She held up her wine glass. “Look. I’ve only had three sips. I’m not drunk. It’s just the truth: an orgasm is the most intense pleasure I know, and I’m afraid that if I stop fucking, I’ll start mainlining. I’m a perfect candidate for a crystal meth habit. I’ll do anything to interrupt the—” “Pain,” I said. “Yeah,” she said. She did that hand-waving gesture of hers. “What do you think is the next step? Call my parents?” I didn’t have a clue how to answer. “They never met her,” she said. “They did ask. I just never thought they asked genuinely enough. I have to live with that, that I kept her from them. I’m sorry.” She looked up at me, her eyes flashing and her thin-lipped mouth open with grief. “The two most stupid words in the language.” Then she did drink the glass of wine, and I poured more for both of us. Crab Orchard Review

u 23

Lucy Jane Bledsoe “Who are you?” she asked again, and so I told her, but briefly, because it was clear to me that she didn’t need to hear my story—not now, not here—about seeing the end of my life and leaving my partner. Yet she listened with what appeared to be full understanding, and then said, “You need to go home.” I nodded. “Stay tonight. Can I sleep with you? Not like that. But I want—” After waiting for her to finish the sentence, and when she didn’t, I nodded again. We rose out of our chairs then and both put on our flannel pajamas. We climbed into the big bed and silently moved toward one another. I thought I was holding her, but she may have thought she was holding me. The storm outside gathered force throughout the night, and I slept little, but I felt tranquil in our cocoon of chance. At dawn a flush of desire warmed me as the sun pinked up the room. I hurried out of bed and made a pot of coffee. The rain had stopped, and the ocean glittered almost obscenely. I stuffed my things into my suitcase as quietly as I could and rolled it out of the house, leaving the door cracked open because it wouldn’t shut without a noisy thunk. A deer standing on the hillside watched me load the suitcase into my car. I badly wanted to walk back up to the porch, for a last look at the sea, but knew my time was up. Just as I was getting into the driver’s seat, Henrietta came running out of the house, breathless, her hair a tangle of curls and that grim set of her mouth freed in a cry of, “Wait!” I waited, and she walked across the gravel driveway in her bare feet, wincing with the sharp pain in her soles, and put her arms around me. Her flannel pajamas were still warm from the bed. She nestled her face into my neck for a second, and then pulled back and gave me a lickerish kiss on the lips. Still no smile or goodbye as she walked backwards, toward the house, tipping a bit from the kiss throwing her out of balance. I climbed into my car, started the engine, and drove home.

24 u Crab Orchard Review

Alex Collins-Shotwell Strike-Slip You’re up on the roof of a house in the Hollywood Hills and

you’re surrounded by a darkness so palpable you can almost wear it. Against the blackness you can see the Coliseum glowing halide-bright to the south. Light travels farther than you’d think. Southeast is downtown, half the height it used to be. West is a sprinkle of lights from generators and Coleman lanterns before the dark spreads across the ocean, a velvety cave that swallows the light whole. If you turned around and crested the hills, you’d see light on the northern horizon, toward Santa Clarita, where you’ve heard they still have power. There are fifty major fault lines and hundreds of minor ones underneath Southern California. They have beautiful names: the Santa Ynez Fault, the Superstition Mountain Fault, White Wolf, San Jacinto, Rose Canyon. They have names that sound like home: the San Gabriel Fault, the San Andreas Fault, the Santa Monica Fault, Palos Verdes, Malibu Coast, Sierra Madre. People in Kansas live watching the skies for tornadoes, people in Florida live watching for hurricanes, worrying about a disaster that might never happen. But you know this: the ground underneath your feet is impermanent. It’s on its way to somewhere else, just like everyone. You don’t wonder if there will be earthquakes, because you know. You and Sam and Elena got lucky because you were outside when it happened, walking back to your apartment with tacos from the truck that was always parked on Vermont. You remember thinking that the sky was redder than usual, and then you stumbled over something in the sidewalk and landed hard on your hands and knees, carnitas scattering across the ground, and you yelled “Shit!” as you fell but no one heard you. Sam and Elena didn’t hear you because they were also on the ground, and you wondered if you were drunk and you didn’t know why you were suddenly so clumsy and then, almost in slow motion, you watched scaffolding fall from a building Crab Orchard Review

u 25

Alex Collins-Shotwell and then you understood that the ground was shaking and it had been shaking for what seemed like so long but couldn’t have been more than three, four seconds. You grabbed for Sam and Elena and the three of you crawled toward each other like kittens and you hung onto them because nothing else was trustworthy: not the street, not the sidewalk, not the cement wall next to you. A crack opened up right down the middle of your apartment building and chunks of drywall started falling out and you stopped looking at anything except the ground that you were absolutely sure would yawn open right there and swallow you. It made the deepest sound you’d ever heard, so low it felt like you heard it with your spine. Asphalt and concrete buckled up around you and every single car alarm was going off and then it stopped and your knees were bruised and your palms were skinned but you were alive. The three of you are as settled as you can be, now, in this house in the hills. It was unlocked when you tried the door one evening, a few days after the earthquake, and since you didn’t have to break in you can lock it behind you. You checked that no one was inside, hiding behind a locked door with a shotgun, and you found a case of wine in the pantry. You sat on the couch and passed a bottle back and forth while you made up a story about the family who lived there, whose pictures were still on the walls: a white woman, an Asian man, their daughter. There was only one car in the garage so you tell each other that they drove away, nevermind that everything in the house is perfectly in place, nevermind that a box clearly labeled EMERGENCY, a box that has ten gallons of water and enough canned food for a week, is still at the bottom of the pantry. They got out, you decided, sitting on their couch, drinking their wine. They didn’t die at school or at work or out running errands. Born in Southern California means born knowing about earthquakes, born under the specter of the Big One that has been coming your entire life. You knew more about it than you did about the moon: you knew the Richter scale; the San Andreas Fault, miles away out in the desert but still a thing to fear; you knew that the northern end of it caused the ground in San Francisco to liquefy in 1906. You knew it was a strike-slip fault, the North American and Pacific plates nuzzling one another at a geologic pace, the ground catching and slipping, catching and slipping, insensible to anything that happened on the surface. You knew, or at least you were always 26 u Crab Orchard Review

Alex Collins-Shotwell told, that strike-slip faults were lateral faults. That California couldn’t sink into the ocean. The earthquake ended and you didn’t believe it. It had been so long—ninety whole seconds, you found out later, staggeringly long for an earthquake—that you thought it never would stop, that you now lived in a world of constant rattling, but it did end and you stood, you looked around, you were okay, you pulled out your phone to call your parents, tell them you were okay, but the network was down and you saw a woman on the corner, one leg trapped in the rubble of her store, garish piñatas and figurines of La Virgen broken everywhere around her, and instead of thinking, you just did. The three of you lifted rubble and pulled people out for hours, you think, and you lost track of where the people went or what time it was. You thought that ambulances and fire trucks would come, and then they didn’t, and then the sun set and they still hadn’t, and that was when you looked up, finally, to see so many buildings crumbled, power lines down, trucks and SUVs rolled over on their sides, asphalt asunder. Then you knew help wasn’t coming, not that night, and it still didn’t occur to you that help might not ever come or that your parents, instead of being worried about you, might not be okay. The sun set over the ocean, over a new shoreline you didn’t know about yet. That night you saw more stars over the city than you’d ever seen before. The next morning, in the house with the door that locks, you find boxes of cereal in the pantry along with evaporated milk and bowls still in the cabinet behind a child lock, probably the reason they’re not smashed on the floor. Sunlight streams in through south-facing floor-to-ceiling windows that aren’t broken for some reason, but you’ve stopped thinking about reasons: some buildings were split in two before they were shaken into rubble and some weathered the quake without a scratch. Some roads are perfectly fine and some crumpled like the icing on a donut. Asking for reasons at this point is useless. Sam walks in and plops a Southern California road atlas onto the kitchen table just as another low rumble starts and everything in the house starts shivering. She puts one hand on the wall and you steady your cereal bowl. You’ve lost count of the aftershocks that have clattered through in the days since the earthquake, these little shifts and adjustments in the earth’s crust. “It was in their car,” Sam says when it finishes. She reaches into the cabinet for her own bowl, fills it with cereal and canned milk. “I Crab Orchard Review

u 27

Alex Collins-Shotwell checked it out. The 5 goes right to Santa Clarita. It’s only twenty-five, thirty miles.” “We can’t walk that far,” says Elena from the next room. She walks in and stands in the kitchen doorway. “It’s less than a marathon,” says Sam. “Of course we can walk it. We could walk it in a day. Two if we walk slow.” “I don’t have good shoes for that.” “Are you serious?” Elena says nothing. “Getting to civilization is worth a couple of blisters,” Sam says in that dismissive tone you know Elena hates. “We’ll bring some bandaids with us.” “I’m not going,” Elena says, and leaves again. “Elena,” Sam says, bowl with cereal and canned milk in one hand. “Elena!” You hear a door slam, and there’s a moment of silence in the kitchen and then you start laughing because this is the exact same kind of argument you had when you all lived in the same apartment together, and you’re sitting here, eating cereal in this beautiful kitchen with the sun flowing in. You laugh so hard you snort, and you look over at Sam for confirmation that this is ludicrous. Instead she watches you suspiciously. The Los Angeles basin sank seventeen feet in sixty seconds. That’s a little over three inches a second; blazingly, scorchingly fast for the earth to move but imperceptible to the people standing on it, already distracted by an earthquake. Even near the ocean, in the beach cities, in Venice or Santa Monica, people wouldn’t notice—not until the water rushed in, not until they were already under, buoyed against the ceiling of a condo near the beach bought after an only daughter graduated from college, a lifelong dream. No one would know until it happened, because it wasn’t going to happen, because the San Andreas is a strike-slip fault. Elena wants you to come to the Observatory with her because she’s too mad at Sam, so you bike over with bikes you’ve found in abandoned houses. It’s on this bluff at the edge of the hills, a perfect view of vast Los Angeles to the south, built in the 1930s before there was so much light, when people could still see the stars. You’re a little surprised it’s standing at all, though it looks like the east wing has 28 u Crab Orchard Review

Alex Collins-Shotwell collapsed. You walk in through the front doors, turn on the flashlight you brought and come face to face with a man wearing a Mayan headdress. He used to be part of the ceiling, pointing to a circular calendar that’s now in pieces around the floor. You remember when you took Sam and Elena there for the first time. Neither had ever been. Sam was new to LA, an eighteen-yearold from North Carolina on scholarship with a convert’s fervor for the city, and Elena had grown up by the beach in Venice with a housekeeper and designer handbags. The three of you walked up from the parking lot at the bottom of the hill and stood looking over the city, the perfect view straight down Normandie Avenue. You stayed for the sunset and you watched the neon in Koreatown flicker to life one sign at a time. When no one was looking, the three of you sat on the railing and dangled your feet over, flip flops hanging down, Los Angeles twinkling between your toes. “I hope the gift shop is okay,” Elena says now. Your flashlight picks out other painted faces and then you move past them, down a staircase, down a sloping hallway, praying that there’s not an aftershock while you’re in here. You and Elena hold hands in the dark because there’s only one flashlight, and you walk through the Gallery of Planets—dead TV screens and orbs on the floor—toward the light and shattered glass that’s the cafe and gift shop. As you step back into the sunlight you hear a click that you’ve only ever heard before in movies. “Stop,” says a male voice. You obey. “Okay, now, just, turn around slowly.” Your heart slams against your ribs and your hands float up almost of their own accord in a universal gesture of surrender, and you turn to find a kid maybe ten feet away, blocking the cafe entrance, with a shock of curly hair and wide eyes, pointing a handgun at you, both arms straight out. He can’t be more than seventeen. “You can’t stay here,” he says. “This is our place.” “We’re just here for a telescope,” Elena whispers. This catches the kid off-guard. “What?” he says. “A telescope.” “Are you fucking with me?” the kid asks. He frowns. “She wants to see if her parents’ house is underwater,” you say, impossibly audible over the sound of your heart. The kid swallows and shifts his weight from one foot to the other. Crab Orchard Review

u 29

Alex Collins-Shotwell Something moves in the back of the cafe, another kid you didn’t see before, his arm held oddly stiff and wrapped in t-shirts. “We can’t give you any food,” the kid with the gun says. “Just the telescope,” says Elena. The kid looks from you to her and back, then turns to the door to the outside and very carefully puts the safety back on, pointing the gun away from everyone. “Sorry,” he says. “You can take a telescope.” “Thanks,” Elena says, and you both turn into the gift shop. You find an unbroken kids’ telescope in the jumble on the floor, and you take some binoculars and a map of the night sky just for the hell of it. When you turn to go the two kids are sitting at a table, talking, the kid with the arm pale and sweaty and miserable-looking. “Is your arm broken?” Elena asks him. “I think so,” he says. He has floppy black hair and caramel-colored skin. She reaches into the backpack she’s carrying and takes out a bottle of Advil. “Here,” she says. You look at her. What if Sam gets a migraine, what if someone sprains an ankle? He takes it, slowly. “Thanks, man,” he says. “There was some here but I went through all of it already. It helps.” The first night after the earthquake, you found emergency services by the lights. Hospitals and fire stations had generators, if they were working, if they weren’t totally destroyed. The Kaiser Permanente hospital in Hollywood was okay and the three of you went there. The absolute human chaos was worse than the minutes after the earthquake: the screaming, the blood, the bones poking out of flesh. You remember one woman so clearly, sitting on the ground against a wall, right side covered in blood and right arm useless, hugging a crying toddler with her left arm, both eyes closed. You felt nauseatingly helpless. That’s where you felt the first aftershock, in the big entrance hall of the hospital, hoping for food or water. This time you knew what it was right away, and you squeezed your eyes shut and held onto a wall, telling yourself it couldn’t get worse, and when the lights went out for a moment you thought maybe you’d died. Next to you at the wall was a bearded guy, maybe in his twenties too, and when the shaking stopped he told you how much Los Angeles had sunk, that Beverly Hills was the beach now. “Great for property values,” you joked, and to your relief he laughed, and then he disappeared in the crowd again. It took you a 30 u Crab Orchard Review

Alex Collins-Shotwell minute to realize what that meant, Beverly Hills on the oceanfront now, all that land west of it underwater. Elena’s been on the roof for an hour with the telescope, looking west. Sam’s inside, packing three backpacks full of water and granola bars from the pantry and cans of baked beans. You walk up behind Elena, and you know she hears you, you’ve made plenty of noise, but she doesn’t move at all, not until you walk over and put a hand on her shoulder. Without looking she hands you the telescope and points. “There,” she says. You look and don’t know what you’re looking for. “From where the 405 is, look a little up and west. Sunset is still above the water, and right before Temescal goes into the ocean, do you see that?” You’re looking and you don’t answer. “The Village School,” she says, her voice rising. You can’t follow her directions and you know it’s impossible to see the high school from where you are. The angle of you and the mountains and the valleys are all wrong. You already went on that goose chase with her that morning—you had a gun in your face too. You don’t see why she gets to pretend that her family is alive. “I don’t think I’m looking at the right spot,” you say. She takes the telescope back. “That’s it,” she says quietly to herself. You take it again and look through, follow the street that she says and you still don’t see anything. “That’s not Temescal,” you say. “Temescal’s underwater.” She grabs the telescope so hard it hurts your eye. “It’s right there,” she says. “That’s just some building,” you say, and you think again of water rushing in, up to the ceiling, and you can’t believe she’s being so stupid. “That’s not the school.” “Yes it is.” “They’re dead, Elena,” you say. “Your parents are dead. Your sister is dead. You’re not. Come inside and help pack. We’re walking to Santa Clarita tomorrow.” She doesn’t look at you, she doesn’t turn, she keeps looking through that damn telescope even though you can see tears falling down her right cheek. There’s silence. “Fuck off,” she finally says.

Crab Orchard Review

u 31

Alex Collins-Shotwell After the quake you didn’t see the ocean for two days, until the three of you were heading north, climbing into the hills, and then you were afraid of it, afraid of how you would react to the sight: Santa Monica, Venice, Marina Del Rey, Malibu, Westwood, most of Culver City, gone, but you looked anyway. Another you thought how beautiful it was, the top of the Mormon temple still shining bright gold in the sun, the tops of every building in the glassy water, the freeways skimming over it like bridges between mountains, the landscape you had always known become new and alien. But at the same time you thought of the water rushing in as the ground shook, and you thought of how you could never do anything about it. After Kaiser Permanente the three of you decided to strike out on your own. There were far fewer people around than you had assumed there would be, and you tried not to think about it. You didn’t make eye contact with the piles of rubble that were the unlucky, old buildings. Anyone in them could still have been alive and you knew you couldn’t do anything to help them. Elena wanted to go back to the hospital, sure that someone was in charge and working on getting everyone out of Los Angeles, but you couldn’t stomach the idea. Sam was the first to break into a house, wrapping her arm in a Dodgers T-shirt she’d found and breaking the window on a front door with a rock and then reaching through to unlock the door like she’d been doing it her whole life. An alarm that didn’t matter went off, and you went inside and found bottled water and blankets and cans of food and no sign of the owners. The nice houses were the most deserted. Sam said that the rich probably got out somehow, since the rich always seem to manage that, but Elena started crying and you didn’t bring it up again. That night you all go to bed in the locked house, Sam in the master bedroom, Elena in the guest, and you in the kid’s bedroom. You and Sam have decided you’re leaving the next morning, and Elena said nothing so you assumed she’d come, she was just still angry with you. You lie wide awake under the pink and purple comforter that belonged to a dead little girl, trying to fall asleep, but instead you’re thinking about your friend Melissa who was a waitress at a sushi restaurant near the beach. She lived in Koreatown, though, so where was she that afternoon? At work or at home? Then you’re thinking about it again, the earth trembling beneath you and then the lights going out, thinking of the water rushing in and pushing you to the 32 u Crab Orchard Review

Alex Collins-Shotwell ceiling. You might never see Los Angeles again. No one might ever see Los Angeles again. You don’t realize you fell asleep until the aftershock wakes you up, a sudden jolt when the earth shifts and then a slow wobble that feels like being on a ship on the ocean. You let it rock you back to sleep. Elena’s gone in the morning. You check every room twice, check that she’s not just hiding in a closet for some reason unknown to you. Finally you sit on the couch, shaking and nauseous. Sam is next to you, staring at the wall across the room. Her eyes are red-rimmed and bloodshot. Yours feel like sandpaper in their sockets. You take her hand. “We should still go,” she says in a voice that is not Sam, that is primal and deep and echoes from somewhere far away. You know she’s right. It will be impossible to find Elena and impossible to get her to leave with you. You know this, but you’re tired of losing people, tired of giving in to the earthquake and accepting this new life, this new Los Angeles. “We should find her,” you say anyway. “We can’t find her.” “She’ll come back.” Sam swallows and you see her jaw clench and unclench. “My parents are still alive,” she says. You say nothing. You imagine water rushing in. “I need to call them, I need to tell them I’m okay.” “We can’t leave Elena,” you say. “She doesn’t have parents. She wouldn’t leave us.” “She did leave us,” Sam says. “We’re probably never going to see her again, and so now I need to walk to Santa Clarita so I can contact my parents and my family who are still alive and then I can go home.” “Give her a day,” you say. You lean forward and put both hands in your dirty hair and lean your elbows on your knees. “No,” Sam says. “Today. We’re leaving today.” “You’re leaving today.” Sam swivels her head toward you and gives you a long look, nothing but her eyes moving over your face. Then she gets up without saying anything, walks into the bedroom she’s been using, walks back out with a pack on her back. She buckles a strap around her waist. “Don’t,” you say. “Give her a day, just give her a day and then I’ll come.” “You’re never going to come.” “We can’t leave her here, not like this, not alone.” Crab Orchard Review

u 33

Alex Collins-Shotwell “You’re letting me go alone.” “You’re not her,” you say. “You’ll be fine, you can handle yourself.” “Yeah,” she says. She looks at you for a long, long moment. “I should have known,” she says. “Known what?” “You wouldn’t leave LA.” You have no response. You suspect she might be right, she might have dug her way to the truth, but the sun is glaring through the windows and Sam is leaving and the city is destroyed and you don’t know a thing right now except that you’re not going with her, which is such a solid fact you could hold it in your hands. “Don’t leave,” you say again. Sam gives you a long, hard hug, and then she walks out the door. You go back to the couch, you lie down, you let the sun come in the windows and shine all over you lying there, for hours. Elena is gone and now Sam is gone and you don’t know what to do, you don’t want to be alone but you couldn’t leave Elena to go with Sam and Elena didn’t even ask you, she just went. The sun slowly rises over the roof of the house so it’s no longer on you, and you think of the boys at the Observatory. They’re someone, at least. You bike over and pull into the parking lot, the sun right overhead, and even from far away it looks different. You don’t know how. The east side is still folded in on itself, the central dome and the west wing still okay, but something else is missing, something’s happened. You go in and see the same Mayan painting, the man who used to point to the calendar, and you look for the long ramp downwards but it’s blocked now, the ceiling caved in. The cafe, you think. You go back outside and walk around the perimeter, in the sunlight, and as soon as you go around the corner you can see that the whole cafe and gift shop are fallen in, shattered glass and 1930s masonry everywhere. You can’t even begin to move the rubble. There’s no way inside and there is nothing except the eerie silence of a city destroyed. The Southern California sun is insistent on your skin, covering you, pressing you down, and you stare and stare at the rubble. You turn and walk to the railing. You sit on it, dangle your feet over, Los Angeles below.

34 u Crab Orchard Review

John Glowney Map Making Geography is blue mostly. Serene sheet, azure mirror, the ink bottle the map-maker capsized across his table: Arabian Sea, Puget Sound. The rest is color-by-border, sovereignty streaked by migrations of refugees. Massachusetts, for example, the color of the paper on which they wrote the Declaration of Independence, China the crimson of communist hordes, India a potter’s clay of beggars, dust, and cow dung. So why this end, among all the ends of the earth, why the thumbtack of destination stabbed here as if by a blindfolded man? It’s the rule of surveys:

Crab Orchard Review

u 35

John Glowney errors are thrown to the North and the West. I fled the plains, the color of the Bible and a mouse’s tail, and L.A., when you looked back, glowed like a motel light in hues of palms and fool’s gold. No banana trees for us, no cornfields unrolled like rugs, only this green estate of steady rain. Only beaches of moss hanging from the spill of an ocean.

36 u Crab Orchard Review

John Glowney

Protest WTO, Seattle, November 30, 1999 It’s a stand-off, and nobody is giving in. The full block of Sixth Avenue in front of the Sheraton is swimming with college students, some dressed as turtles or butterflies, as if in a kindergarten pageant, some carrying signs, banners, flags, everything from Earth First to Free Tibet. A misting rain mounts its own rally and uniformed cops in heavy black shoes and black helmets make a barricade of bodies across the Union St. intersection. So when a scrawl of smoke from a teargas canister hisses up, intense and white as silk, the entire crowd turns like a school of fish —you can see the reflective rain jackets, the bright colors flashing like wind-stirred leaves in a maple— and retreats fifty feet, then turns and again holds its ground. The smoke makes a white dissolving wave high and cold in damp sunlight on the brick cornices and glass facades like the ghost wake that marks our journey from here to there

Crab Orchard Review

u 37

John Glowney sweeping along the bare, wet corridor of pavement between the line of cops and the protesters, shining, then fading, the gulf between them crossed with the slogans of rebellion that boil out of the riotous protest that is their hearts, the lingua franca of the young, stray words, mere breath.

38 u Crab Orchard Review

John Glowney

Out on Turnigan Arm, Resurrection Bay Ptarmigan grouse limp the rutted gravel road, dumb as loaves of bread, a Denali red fox slinking fireweed a few yards behind, showing, like an iceberg, only 10% of his guile. The mud flats glisten in the massive tidal retreat, glitter like sequined dresses, and from the tourist turnout above the shutters of Kodak and Canon blink and click at the great exposed bottom. In the Anchorage Zoo the sad llamas chew the cold edges of the rain and ponder their curious fate. The cliff-nesters’ eggs wobble like tops above the long plunge into Resurrection Bay, and it’s all plunge—off the rocky promontories, the cormorants and the common murres, the bedizened puffins hurling themselves into the gray-blue waters—all chop, churn, surge, thrash. The Dall sheep on the steep hillsides, born to this damp white cloudiness, are perhaps on their way to heaven and light-toed as ballerinas Crab Orchard Review

u 39

John Glowney answering the perilous question of the narrow path. Bald eagles mate for life and beyond any vow we care to voice, the broad nests sometimes so built and overbuilt the tree limb splinters, and still the pair returns, year upon year, to repair and live amid the precarious, accumulating wreckage.

40 u Crab Orchard Review

John Glowney

The Whale Skeleton at Long Beach, Washington Now would I give a thousand furlongs of sea for an acre of barren ground… —The Tempest I. I. 44 They’ve roped him off with a rusting anchor chain, a museum of one, resurrected from the warbling surf-song that buried forty-five feet of whale under stiff sand out of reach of the bleaching sun in homage to William Clark’s 1806 journal entry noting the bones of a gray whale run aground in the cold fog of an unnamed coast. So now he’s back on the beach, one of the tribe that turned its back on land turned back again, long skeleton, missing ribs, the vaults of those enormous lungs that once held a squall of breath for hours, the grayish, warm-blooded body, scarred by parasites, the broad lips for benthic feeding, fluke, flippers, the great cloak of blubber we sawed off to light our rooms,

Crab Orchard Review

u 41

John Glowney the great, four-chambered heart—heavy, like ours—all gone. A shaggy, many-stemmed dandelion plant blooms where the cavernous stomach processed tons of plankton. The empty brain-socket flutters with shreds of dune-grass. Every summer the local merchants host a kite festival on the whale’s beach, the sky for a week sprayed with colorful plastic or cloth sails that twitch and throb in the high sea-breezes, almost out of sight. And season after season the convoys of pods tack south, long voyages along far, dusty trails so secret and old only the whales can imagine them.

42 u Crab Orchard Review

Tom Griffen Homer Stevedore I drive up the dirt road after a twenty-four hour shift pitching fish on Kachemak docks, unloading angry boats swollen with the salmon I’ve gotten so good at sorting. Pink, silver, king and red— I can swipe them off the conveyor and chuck them in metal bins faster than guys half my age. My Jeep floats past foggy halibut outlined in lodgepole pines. I smell of fish rot and skunk from the junky old weed I smoked with fugitives from the lower 48. We hurl snowballs at forklifts and at guys with clean overalls until the echoing horn of a trawler zaps us sober. Back to work. We scatter and wave our hats, then draw straws to see who’s going in the hold to get covered in guts with no breaks all day. There’s a guy who always volunteers and is known for putting a flounder’s eye, big as a peach pit into his mouth— then pretend to swallow it

Crab Orchard Review

u 43

Tom Griffen and sometimes doing so but not on purpose. It’s morning. I think. I should have passed on the beers and gotten some sleep instead. I speed fifteen miles per hour past glowing views of the Spit up the pitch to my cousin’s cabin. I stop only to pick up a dirty guy needing a lift. He asks me to drop him at a church some five miles ahead. He’s been hitching since Anchorage, but Ohio before that. He says I look tired but I can’t be as tired as him. He says he’s having trouble with allergies or something. He snaps into a fit of scratching, says his eyes are filling up with tiny, flesh-eating worms. He asks if God can help. I tell him that’s impossible, the worms anyhow. He covers his face with his hands and I tell him I don’t know much about God. His weeping keeps me awake.

44 u Crab Orchard Review