Crab Orchard Review

In this volume:

•

•

REVIEW

in print since 1995

ISSN 1083-5571 $14.00

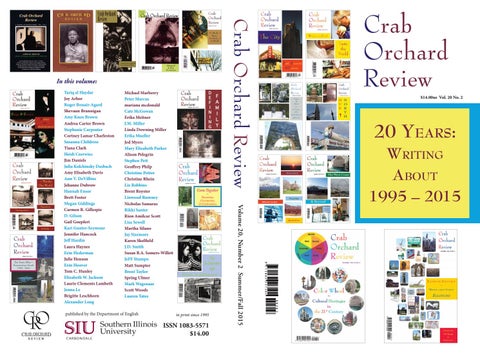

20 Years: Writing About 1995 – 2015

00202

CR AB ORCH AR D

published by the Department of English

$14.00us Vol. 20 No. 2

9 771083 557101

CO R

Michael Marberry Peter Marcus mariana mcdonald Cate McGowan Erika Meitner J.M. Miller Linda Downing Miller Erika Mueller Jed Myers Mary Elizabeth Parker Alison Pelegrin Stephen Pett Geoffrey Philp Christine Potter Christine Rhein Liz Robbins Brent Royster Linwood Rumney Nicholas Samaras Rikki Santer Rion Amilcar Scott Lisa Sewell Martha Silano Jay Sizemore Karen Skolfield J.D. Smith Susan B.A. Somers-Willett JeFF Stumpo Matt Sumpter Brent Taylor Spring Ulmer Mark Wagenaar Scott Woods Lauren Yates

Volume 20, Number 2 Summer/Fall 2015

Tariq al Haydar Joy Arbor Roger Bonair-Agard Shevaun Brannigan Amy Knox Brown Andrea Carter Brown Stephanie Carpenter Cortney Lamar Charleston Susanna Childress Tiana Clark Heidi Czerwiec Jim Daniels Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach Amy Elisabeth Davis Ann V. DeVilbiss Jehanne Dubrow Hannah Ensor Brett Foster Megan Giddings Carmen R. Gillespie D. Gilson Gail Goepfert Kari Gunter-Seymour Jennifer Hancock Jeff Hardin Laura Haynes Erin Hederman Julie Henson Erin Hoover Tom C. Hunley Elizabeth W. Jackson Laurie Clements Lambeth Jenna Le Brigitte Leschhorn Alexander Long

Crab Orchard Review

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

A Journal of Creative Works

Vol. 20 No. 2

“Hidden everywhere, a myriad leather seed-cases lie in wait…” —“Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” Thomas Kinsella Editor & Poetry Editor Allison Joseph

Founding Editor Richard Peterson

Prose Editor Carolyn Alessio

Managing Editor Jon Tribble

Editorial Interns Teresa Dzieglewicz Chelsey Harris

Assistant Editors K Brattin Toni Judnitch Laura Ruffino Mary Kate Varnau

SIU Press Interns Philip Martin Alyssha Nelson Board of Advisors Ellen Gilchrist Charles Johnson Rodney Jones Thomas Kinsella Richard Russo

Summer/Fall 2015 ISSN 1083-5571

Special Assistants Brent Glays Drew Hemmert John McCarthy

The Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Address all correspondence to:

Crab Orchard Review

Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901 Crab Orchard Review (ISSN 1083-5571) is published twice a year by the Department of English, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Subscription rates in the United States for individuals are $25 for one year, $40 for two years, $50 for three years; the foreign rate for individuals is $40 for one year. Subscription rates for institutions are $28 for one year, $56 for two years, and $84 for three years; the foreign rate for institutions is $48 for one year. Single issues are $12 (please include an additional $10 for international orders). Copies not received will be replaced without charge if notice of nonreceipt is given within four months of publication. Six weeks notice required for change of address. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Crab Orchard Review, Department of English, Faner Hall 2380 Mail Code 4503, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 1000 Faner Drive, Carbondale, Illinois 62901. Crab Orchard Review considers submissions from February through April, and August through October of each year. Please visit our website, CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu, for the latest guidelines, calls for submissions, and contest information. Most of our submissions are now through CrabOrchardReview.submittable.com, so please do not send submissions via postal mail unless you are certain we are open for postal submissions at that time. Crab Orchard Review accepts no responsibility for unsolicited submissions and will not enter into correspondence about their loss or delay. Copyright © 2015 Crab Orchard Review Permission to reprint materials from this journal remains the decision of the authors. We request Crab Orchard Review be credited with initial publication. The publication of Crab Orchard Review is made possible with support from the Chancellor, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Department of English of Southern Illinois University Carbondale; and through generous private and corporate donations. “Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois,” 18 June 2015, 4200 copies printed, order number 117496. Lines from Thomas Kinsella’s poem “Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” are reprinted from Thomas Kinsella: Poems 1956-1973 (North Carolina: Wake Forest University Press, 1979) and appear by permission of the author. Crab Orchard Review is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Visit Crab Orchard Review’s website:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

Crab Orchard Review and its staff wish to thank these supporters for their generous contributions, aid, expertise, and encouragement: Barb Martin, Karl Kageff, Amy J. Etcheson, Bridget Brown, Lynanne Page, Angela Moore-Swafford, Wayne Larsen, and Kristine Priddy of Southern Illinois University Press Bev Bates, Heidi Estel, David Lingle, Kathy Reichenberger, Joyce Schemonia, Kelly Spencer, and Bernadette Summerville Shaylin Carlton, Rebekah Durig, Chloe Hesler, and Sarah Jilek Dr. Elizabeth Klaver (chair), Pinckney Benedict, Beth Lordan, Judy Jordan, Scott Blackwood, and the rest of the faculty in the SIUC Department of English Division of Continuing Education SIU Alumni Association The Graduate School The College of Liberal Arts The OfďŹ ce of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost The Southern Illinois Writers Guild

Crab Orchard Review is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency.

Crab Orchard Review wishes to express its special thanks to our generous Charter Members/Benefactors, Patrons, Donors, and Supporting Subscribers listed on the following page whose contributions make the publication of this journal possible. We invite new Benefactors ($500 or more), Patrons ($200), Donors ($100), and Supporting Subscribers ($50) to join us. Supporting Subscribers receive a one-year subscription; Donors receive a two-year subscription; Patrons receive a three-year subscription; and Benefactors receive a lifetime subscription. Address all contributions to:

Crab Orchard Review Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901

CHARTER MEMBERS*/BENEFACTORS John M. Howell* Rodney Jones Richard Jurek Joseph A. Like Greg & Peggy Legan* Beth L. Mohlenbrock* Jane I. Montgomery* Ruth E. Oleson* Richard “Pete” Peterson Peggy Shumaker

Dan Albergotti Carolyn Alessio & Jeremy Manier Anonymous Pinckney & Laura Benedict Edward Brunner & Jane Cogie* Linda L. Casebeer Noel Crook Dwayne Dickerson* Jack Dyer* Joan Ferrell* John Guyon*

PATRONS Robert E. Hayes Chris Kelsey Jesse Lee Kercheval Lisa J. McClure Anita Peterson

Eugenie & Roger Robinson Nat Sobel Betty Tribble David & Laura Tribble Clarisse Zimra

DONORS Lorna Blake Chris Bullard Heidi Czerwiec Charles Fanning Jewell A. Friend John & Nancy Jackson Reamy Jansen Rob & Melissa Jensen Elisabeth & Jon Luther

Charlotte and Gabriel Manier Lee Newton William Notter Lisa Ortiz Ricardo Pau-Llosa Lucia Perillo Angela Rubin Hans H. Rudnick William E. Simeone

SUPPORTING SUBSCRIBERS Joan Alessio Joanna Christopher K.K. Collins Corrine Frisch John & Robin Haller Zdena Heller Karen Hunsaker Lee Lever

Charlotte McLeod Peggy & Albert Melone Nadia Reimer Lee Robinson Catherine Rudnick Peter Rutkoff Victoria Weisfeld

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

Summer/Fall 2015

Allison Joseph

Volume 20, Number 2

Editor’s Prologue: Twenty Years

1

Fiction Amy Knox Brown Megan Giddings

A Recipe for Mice

3

I Invented Longing

35

Linda Downing Miller

The Decider

37

Stephen Pett

The Elizabeth Smart Memorial Hike

69

Rion Amilcar Scott

The Legend of Ezekiel Marcus

96

Brent Taylor

Why Aren’t You Dancing?

112

Nonfiction Prose Tariq al Haydar

Machine Language

137

Stephanie Carpenter

Connection Refused

144

Laurie Clements Lambeth

A Good Twenty Years

159

Brigitte Leschhorn

Ghosts March in Ferguson, MO

184

Spring Ulmer

Bubbles

204

Poetry Joy Arbor

When God Chose Love over Truth

22

Roger Bonair-Agard

In which Jay-Z asks me to come back to Brooklyn

24

Shevaun Brannigan Andrea Carter Brown Cortney Lamar Charleston

Lucky Ones

26

Getting Out the Vote

28

“Still Life with Torso of Cornrowed Neo-Soul Sanger”

32

Susanna Childress

Ten Long Weeks at Sea

34

Tiana Clark

Particle Fever

50

Heidi Czerwiec

An Ode to Iron Chef

52

Jim Daniels

Filling Out the Health Evaluation Questionnaire Tough Guys on Facebook Declaring Bankruptcy

53

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

For the Journalists Who Write About Ukraine

59

Amy Elisabeth Davis Ann V. DeVilbiss Jehanne Dubrow

Untethered 61

Hannah Ensor

54 56

The Murder Cycle

64

[To a Navy Wife, in Maryland] Reunion Porn

80 81

Spectacular 03: Super Bowl XLVI

82

Brett Foster Carmen R. Gillespie D. Gilson

George Clooney

83

Darkness Visible: The Turns of the Century, 1999 The Biggest Loser The Discovery Channel The Today Show

85

Mug Shots

89

Gail Goepfert

Facebook Newsfeed: So Much This and That

90

Kari Gunter-Seymour Jennifer Hancock

Kandahar Province

92

Contingency Plan, Aquarium of the Americas New Orleans, 2005

94

Jeff Hardin

The Widening Rift

122

Laura Haynes

Infinity is a number you will never arrive at,

124

Erin Hederman

Why I Sometimes Pretend I’m BeyoncÊ

126

Julie Henson

In the Aeroplane over the Sea

128

Erin Hoover

Girls

130

Tom C. Hunley

Officer Down

132

Elizabeth W. Jackson

Dolphin Talk

134

Jenna Le

Sonnet Written on the Way Home from the Cinema Richard III

135

Alexander Long

On Forgiveness

146

Michael Marberry

Weekly Apology

148

86 87 88

136

Peter Marcus

Rumi Returns to Mazar-I-Shair Marathon

150 152

mariana mcdonald

Guéckédou

154

Cate McGowan

Inaugural Poem, January 20, 2001

156

Erika Meitner

Your Rivers, Your Margins, Your Diminutive Villages The Onion headline says “Keith Richards’ Housekeeper Has Braced Herself for Finding Dead Body Every Morning Since 1976”

168

J.M. Miller

The Art of Genocide

172

Erika Mueller

Disturbance

173

Jed Myers

Burning Man

174

Mary Elizabeth Parker

Doppelgänger: The Flip Side of Your Yearning

179

Alison Pelegrin

My Daguerreotype Boyfriend

181

Geoffrey Philp

Elegy for Ferguson

183

Christine Potter

Los Alamos, on the 50th Anniversary of the Trinity Test

189

Christine Rhein

Not Fling.com Body Painting

191 192

Liz Robbins

Columbine Video

194

Brent Royster

Epilogue for the Wrong Y2K

196

Linwood Rumney

Banana Workers in Limón, Costa Rica

198

Nicholas Samaras

Myself Among the Many Selves

200

170

Rikki Santer

Hashtag Voyeur “A Swift and Fatal Luge Plunge, and Then an Abyss of Sorrow”

201 202

Lisa Sewell

Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque

218

Martha Silano

SkyMall Pantoum

221

Jay Sizemore

Hope is a thing with blasters

223

Karen Skolfield

Soldiers’ ‘Fun’ Photo with Flag- Draped Coffin Sparks Outrage

224

J.D. Smith

Zombie Requiem

225

Susan B.A. Somers- Willett

The Artist Is Present

226

JeFF Stumpo

Against Itself Cannot Stand

228

Matt Sumpter

Still Life with X-Files

230

Mark Wagenaar

Elegy

231

Scott Woods

The Janitor of High School Musical Speaks

232

Lauren Yates

Love Poem for Cher Horowitz

234

Contributors’ Notes A Note on Our Cover

235 243

Contributors and Cover Artists 1995 – 2015

244

The 2015 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction We are pleased to announce the winners of the 2015 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction. The winners were selected by the editors of Crab Orchard Review. In poetry, our winner is Liz Robbins of St. Augustine, Florida, for her poem “Columbine Video.” In fiction, the winner is Stephen Pett of Ames, Iowa, for his story “The Elizabeth Smart Memorial Hike.” And in literary nonfiction, the winner is Spring Ulmer of Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, for her essay “Bubbles.” The winner in each genre category—Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction—is published in this issue and received a $2000.00 award. All entries were asked to fit the topic of the Summer/Fall 2015 special issue, “20 Years: Writing About 1995–2015,” focusing on writing exploring work that covered any of the ways our world and ourselves have changed due to the advancements, setbacks, tragedies, and triumphs of the last twenty years. Visit us online. Crab Orchard Review’s website has information on subscriptions, calls for submissions and guidelines, contest information and results, and past, current, and future issues:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

The Winners of the 2015 COR Special Issue Feature Awards in Poetry, Fiction, and Literary Nonfiction

2015 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Poetry

“Columbine Video” by Liz Robbins (St. Augustine, Florida)

2015 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Fiction

“The Elizabeth Smart Memorial Hike” by Stephen Pett (Ames, Iowa)

2015 Special Issue Feature Award Winner in Literary Nonfiction

“Bubbles” by Spring Ulmer (Chester Springs, Pennsylvania)

Allison Joseph Editor’s Prologue: Twenty Years Crab Orchard Review is a literary journal that wasn’t supposed to exist. Dr. Richard Peterson, our founding editor and former English department chair at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, was told in the early 1990s that funds for a journal existed, but for a number of years he couldn’t find a staff to make a journal a reality. In 1994, when I, along with Jon Tribble and Carolyn Alessio, was hired to teach at SIUC, all of a sudden Dr. Peterson had a ready, willing, and able editorial staff. I had been an editor with Indiana Review; Jon had been both an editor and the business manager of Indiana Review; Carolyn had ample editorial and professional experience. We were all ready to discover new voices, publish stories, poems, and essays, and put SIUC and Carbondale on the map as a center for creative writing. But as with many things in academia, things weren’t quite what they seemed. As long the magazine was just an idea, the money was there. As soon as idea became action, those funds mysteriously disappeared. Dr. Peterson (or, as those who know and love him call him, “Pete”) would not be deterred (a fact I attribute to Pete being a rather tenacious man from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and he proceeded to fundraise (long before Kickstarter, even) for that very first issue. He sought funding for the journal’s first issue from people who weren’t in love with the set of administrators who denied our initial funding. Our joke for all the years that followed has been that Crab Orchard Review began as a magazine paid for by spite. But spite can only take a literary journal so far. After that first issue, we found ourselves back at square one—how to pay for another issue. Fortunately, Dr. Charles Fanning, our departmental expert in Irish and Irish-American Studies, offered to fund our next issue if we would focus it on Irish and Irish-American literature. The issue would premiere at the American Conference on Irish Studies, which was to be held in Carbondale that academic year. We rose to Crab Orchard Review

u 1

Allison Joseph – Editor’s Prologue the challenge, produced the issue, and established our tradition of publishing special topic issues, alongside our general issues. Two issues a year for twenty years means a lot of things—lots of late nights in Faner Hall, deciding on that poem or that story or that essay. Two issues a year for twenty years means we’ve seen a lot of changes—we’ve gone from huge boxes of postal paper submissions to almost all electronic ones, from library hunts for information to Google searches, from bundling up a package when an issue is complete and shipping it to the printer via Federal Express to uploading PDF files at our printer’s website in a matter of seconds. The technology of executing the magazine may have changed, but our commitment to being “a magazine that writers admire and readers enjoy” hasn’t. From the beginning Jon Tribble, Carolyn Alessio, Dr. Richard Peterson, and I wanted Crab Orchard Review to publish lively, admirable, accessible, and accomplished writing. We wanted the widest readership possible and the widest range of writers sending us work. We wanted the journal to be a learning laboratory for all of our undergraduate and graduate interns and our graduate-level assistant editors, and we couldn’t have done our work without them. The work hasn’t been easy, but it’s been so worth it to be part of the conversation about literary journals and contemporary literature in the United States during these past twenty years. I wouldn’t trade a minute of it and I’m proud to have been part of bringing this magazine to life for two decades, providing a home to the work of over 1,700 poets, writers, and artists. I hope you have enjoyed this journey we’ve been on and are looking forward what the future holds for Crab Orchard Review and its editors, staff, writers, and readers.

2 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown A Recipe for Mice On the last day of that cold January of 2007, as the newspapers

crowed about soaring stock prices and rising home values, Burris Killian’s wife Mary found a kitten huddled in one corner of their barn. A black kitten with gold eyes, who—as Mary related to Burris—tilted its head at Mary, then rose on his back legs and turned in a pirouette. How could she resist? She and Burris sat in the living room, the kitten curled on her lap, Mary’s fingers stroking its head. Of course she couldn’t resist. They’d been married almost fifty years; Burris loved his wife, and he’d learned to pick his battles. He’d always believed that barns were the best places for cats, but even as Burris opened his mouth to share this observation, the kitten hopped off Mary’s lap, walked over to Burris, and stood on his hind legs. Swaying a little, he turned in a circle and then dropped back on all fours. Burris had to admit that the trick was—he’d have to say “cute,” though that wasn’t a word he normally used. In the two days between the kitten’s appearance and Mary’s death, they talked about what to name the animal. “Maybe Burris, Junior,” Mary suggested on the last night they sat in the living room together, as they always did after supper, a fire crackling in the fireplace. “What about Dancer?” Burris offered. Mary tilted her head. On her lap, the kitten tilted his head in the opposite direction, both of them indicating they didn’t think much of his idea. “Maybe not Dancer,” Burris conceded. “How about Mac?” Mary said. Burris shrugged. He thought it would be strange to call the small creature by the name of the barrel-chested neighbor who’d owned the land abutting theirs. The mention of Mac’s name reminded him of news he’d heard that afternoon at the grain elevator, where the area farmers gathered to trade gossip. “Speaking of Mac,” he said, “I guess his kids plan to sell the farm.” Crab Orchard Review

u 3

Amy Knox Brown “Well,” Mary said. That one word held the entire population of other words, sentences, and paragraphs they’d uttered since Mac’s son had hauled Mac off to live in California a year earlier, gotten control of the land, and let the fields go to weeds: the venality of the children; their cruelty in uprooting an old man from the land his father and grandfather had farmed; the possibility (or probability) that the land would be sold. “Well,” Mary said again, and Burris knew she meant Now we have to wait and see what happens next. In the middle of the night, Burris felt a soft patting against his face that he sensed didn’t originate from human hands. He opened his eyes. The kitten was tapping his cheek. Waking him up in the middle of the night! This, Burris thought, was the reason cats needed to stay in barns. He reached out to wake Mary—a gesture of retaliation, he knew, even as he did it—but his wife’s side of the bed was empty. Burris sat up. He and the kitten stared at each other for a long moment, and Burris hauled himself off the mattress. He followed the kitten into the kitchen, where he found Mary lying on the floor, a glass tipped over next to the sink, water dripping off the counter. He dropped to his knees to feel her pulse. Her skin was cool beneath his fingers. Maggie, the oldest child, flew in from Oregon. David drove from Pennsylvania. They dropped suitcases in their childhood bedrooms and sat in the living room, bickering over which television show to watch. How long since the two of them had been home together? Burris wondered. Years, he thought, possibly decades. They’d both left the farm for college, then departed for their respective coasts. Maggie was a nurse. She made dutiful weekly Sunday-afternoon phone calls. David taught English at a college whose name perplexed Burris: Indiana University of Pennsylvania. David sent letters once or twice a month. Although Burris saw bits of himself and Mary in the children— David had inherited Mary’s sharp tongue (but not her soft heart), Maggie’s eyes were the exact blue of Burris’—they seemed now like strangers. Bossy strangers. They arranged the funeral and wrote the obituary for the newspaper; David prepared dinners of mysterious ingredients (What was jicama slaw? What was wrong with cabbage slaw?). The day after the funeral, Maggie began burrowing into closets before Burris stopped her. “We need to get this place cleaned out so you can sell it,” Maggie said. She held a box that said “photos” in Mary’s writing. She lifted one 4 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown flap; the box held skeins of yarn, ribbon, and squares of fabric. “One person can’t take care of a house this size, and—” “No.” Burris reached for the box. Maggie held on, and he was forced to give the cardboard a sharp tug to get it out of her hands. “Yes. Sell this place, you can get a little condo in the retirement community around the corner from where I live, and—” “No,” Burris said again. He replaced the box in the closet. He thought of Mac being dragged away from the farm next door. That was not going to happen to Burris. “I’m staying right here.” The children went back to their own lives, threatening monthly visits that Burris was confident would never transpire. He left Mary’s clothes in their closet, her tube of lipstick in the drawer in the vanity, her ashes—which he planned to scatter somewhere of significance—in an urn on the mantel of the fireplace. Her cookbooks remained in their neat row on the Hoosier cabinet in the kitchen. He allowed himself to think, She’s not really dead, she’s gone to town. Not dead; in the barn. He knew this wasn’t a good idea. He knew it wasn’t healthy. Still, he couldn’t help himself. He leafed through her old cookbooks, looking for recipes she’d marked with notes: Good with cinnamon ice cream; or Won’t make this again, about a stew containing hard-boiled eggs and curry that Burris remembered with revulsion. He examined the pages of Henley’s Eighteenth Century Formulas: Recipes and Processes, which they kept with the cookbooks, though the recipes weren’t for food, but rather for dyes, oils, and veterinary remedies. The oldest book in the house, it had belonged to Mary’s great-grandfather, and the pages were the color of weak tea and dotted with brown splotches, like age spots on an old man’s hands. Henley’s also contained a chapter of formulas for creating animals and insects. Burris read over the quote that opened the section: In The History of Animals, Book I, Aristotle wrote that “Some animals spring from parent animals…whilst others grow spontaneously and not from kindred stock; and of these instances of spontaneous generation, some come from putrefying earth or vegetable matter, as is the case with a number of insects, while others are spontaneously generated in the inside of animals out of the secretions of their several organs.” Burris remembered reading the maggot recipe aloud to Mary: Leave a square of beef in shade. In two days, it will produce maggots. He remembered how she’d laughed. Now, he saw a notation in the margin, Crab Orchard Review

u 5

Amy Knox Brown next to “square of beef.” Mary had written, Works with chicken, too. Burris felt himself smiling. She’s not dead. She’s just away for a little while. He sat down in the kitchen chair and let the kitten jump on his lap. He tried to remember what they’d decided to name him. Fifty acres wasn’t a huge farm; it wasn’t even a big farm, but the fifty acres in Lebanon, Kansas—the precise center of the United States—had been in Burris Killian’s family for a hundred years. The land faithfully produced corn and soybeans to sell, and alfalfa to feed the cattle Burris raised. There was plenty of room for a chicken house and pigpen, space for an enormous garden. In other words, as Burris was fond of saying, the farm was the right size to keep you alive without killing you. At the grain elevator, the other local farmers—some of whom owned more land, some of whom owned less—couldn’t dispute that kind of wisdom. They nodded and looked down at their hands. By the time Mary died, they’d cut back; the pigs had been sold off, and then the cattle, except for a little bull named Zeke that had made himself into a kind of a pet. In the spring of 2007, Burris began planting his acres of corn, but he decided to let the land reserved for soybeans revert to prairie, and he staked out a smaller garden. A developer had purchased Mac’s farm, for what was reported at the grain elevator as an astonishing sum of money. From his tractor, Burris watched a bulldozer smash into Mac’s old farmhouse. Dump trucks hauled away crumbling sheets of drywall and broken two-byfours. Excavation machinery chewed holes in the earth. A billboard appeared at the intersection of the highway and County Road 2: Find your dreams in Emerald City! Phase I of 5 in process: Three and four bedroom, three bath homes. No money down! Low interest! You’re not in Kansas anymore! Of course the last sentence made no sense: the development was right in the middle of Kansas. Burris felt his eyes narrow in disdain every time he drove past. The houses rose like toadstools after a spell of dampness. The speed with which each dwelling was erected surprised Burris; he’d thought it would take weeks or even months for a house to be built. But the dozen houses the developer managed to squeeze onto the five acres closest to Burris’ property were completed, it seemed, in a matter of days. Three of the houses were situated so that their backsides stood only a few feet from Burris’ lot line, casting narrow shadows down on the area where he planted his garden. On his knees, patting dirt over 6 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown basil seeds, Burris watched as families in rumbling Hummers arrived. They looked through the houses, and sold signs appeared in the yards, one by one. The bulldozers roamed over the yet-unbuilt part of Mac’s land, leaving cavernous holes. He heard Mary’s voice in his head: It might not be as bad as you’re thinking. You know I don’t like change, he thought. I know that, Burris. He could hear that tinge of sharpness to her voice. There’s no use in borrowing trouble. The families moved into Emerald City. The fathers who lived in the houses next to Burris’ lot line introduced themselves, hollering down from their decks one Saturday in early June when Burris was out checking his bean plants for aphids. They all seemed to have a variation of the same name: Tyler, Taylor, Tanner. Tyler was stocky, Taylor was bald, Tanner was tan. Burris nodded at each man in turn. He said, “Nice to meet you.” He crushed an aphid between his thumb and index finger. A week before the summer solstice—the longest day of the year—Burris sat on the rear stoop in a straight-backed chair brought from the kitchen. He liked to sit here, ten or fifteen feet from his cornfield; if he listened closely, he could hear, under the soft rush of the wind, a faint creaking, a straining, as the corn dug its skeletal toes into the earth and stretched its green arms upward. Before Mac was hauled off to California, he and Burris had held a yearly competition with their corn: each man selected a particular plant, measured it every evening and again the following morning, and then reported the results to his neighbor. Grew an inch last night. Oh yeah? I got an inch and a quarter. Huh. Let me see. Guess you’re right. Guess you did. Burris had always written his numbers down in a little notebook he kept tucked among the cookbooks in the Hoosier cabinet. He tied a red ribbon around the chosen stalk to make sure he’d be able to distinguish it from the other plants. He named the plant he was tracking, alternating yearly between male and female names, the way the weather forecasters did with hurricanes. By harvest, the sun had bleached the color from the ribbon; the wind had shredded it to tatters. Burris hand-harvested the ear from his special plant and took it inside, where he carefully stripped away the husk and silk. Mary Crab Orchard Review

u 7

Amy Knox Brown boiled the ear in salted water to which she’d added a little milk. They slathered the cooked ear with butter, a shake of pepper, and broke it in two to share. They sat at their kitchen table and savored each kernel as it burst between their teeth and filled their mouths with sweetness. Just yesterday morning he selected the plant he’d monitor this summer, the summer of 2007. He’d retrieved a length of red ribbon from the box marked “photos” and tied it around the narrow stalk. He named the plant Mary. As the sun lowered, the neighbors came outside. The parents sat out on their five-by-eight-foot decks, holding glasses of wine the color of urine. They screamed greetings to each other and raised their glasses. The children screamed, too, chasing each other through the yards, dragging sticks across the sides of dog kennels, setting the dogs to barking. One of the children tripped and fell. A louder burst of screaming was followed by an impatient voice: “Just one more minute. Let Mommy finish her wine. Then we can have ice cream for dinner!” “I don’t want ice cream for dinner. I want macaroni!” No one could hear the corn grow, even if he was paying close attention. Burris sighed. He hoped they’d go in soon; the evening might be saved if silence descended and he could remain here on his back stoop and wait for the first fireflies to appear. As the sky darkened, a wink of light flashed in the back corner of Burris’ yard. One wink, then another, and then his whole yard— as well as the yards of Emerald City—filled with fireflies. The insects dipped, rose, and blinked. Burris clasped his hands across his stomach and watched. In the neighboring yards, the children screamed at the sight of the blinking lights and chased after the fireflies. One child managed to catch an insect right at the edge of Burris’ property. The child’s fist closed over the bug, hard, and then the child—a boy—smeared the smashed insect against his face. For a moment, the boy’s skin glowed, and the other children squealed in amazement. For the next several nights, the children were out killing fireflies, smashing the bugs against their skin, and, with their momentarily illuminated faces, chasing each other through Burris’ cornfield. The corn was only a couple of feet high, at that phase where it could be easily trampled, and when Burris checked the field on Saturday morning, a big swath of his corn plants had been crushed against the ground. 8 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown The plant he’d tied with a ribbon was broken off near its roots, leaves already curling brown, dying. No respect, Burris thought. He looked over at Emerald City. Right now, just after sunrise, the development was as quiet as the area used to be when it was still Mac’s farm. He imagined Mary examining the trampled corn, her eyes narrowing. “Well,” she’d say, and Burris would know exactly how to proceed. In the silence, Burris thought he heard Mary’s voice: Look in Henley’s. “All right, then,” Burris said aloud. In the house, he opened Henley’s Eighteenth Century Formulas: Recipes and Processes and leafed through the pages. He read Jan Baptiste van Helmont’s recipe for scorpions: Carve an indentation in a brick, fill it with crushed basil, and cover the brick with another, so that the indentation is completely sealed. Expose the two bricks to sunlight, and you will find that within a few days, fumes from the basil, acting as a leavening agent, will have transformed the vegetable matter into veritable scorpions. He imagined reading the recipe to Mary, Mary nodding and saying Worth a try. Outside, Burris pushed his wheelbarrow behind the barn and gathered three pairs of bricks from the pile he kept there. He wheeled the bricks to the front of the house, where the sun shone hard all day. He chiseled indentations as directed. Next, in his garden, he knelt by the largest basil plant. He felt to the end of each leaf and used his thumbnail like a knife to detach it from the stem. Holding the bouquet of leaves, he prepared himself to stand. A shadow fell over the garden: Tyler, the stocky neighbor whose tiny yard was one of the three abutting Burris’ lot. Tyler was the father of the boy Burris watched kill the first firefly. Burris looked up under the bill of his cap. “Morning,” Tyler said. “Morning.” Burris set his left hand against his left knee and told his muscles to move. His leg straightened; he brought his right foot against the ground; he was upright. He tucked the basil leaves in the front pocket of his overalls. “Making some bruschetta?” Tyler asked. Burris had no idea what bruschetta meant. It sounded like a pejorative name for a mean Italian grandma. He shook his head. “Think we’ll get any rain?” Tyler was holding a tank of herbicide, Crab Orchard Review

u 9

Amy Knox Brown which he swung back and forth while he talked. “I want to put down some weed killer, and it says not to do it if it’s going to rain.” The sky was the color of sheet metal, with just the slightest touch of blue near the horizon. No clouds. A stiff, low wind blew. The weather this morning was the kind that would prompt Mary, when she stepped outside to water her geraniums, to remark, “It’s going to be a scorcher.” “Doubt it.” Burris looked at the neighboring lawns, smooth expanses of recently laid sod. “But doesn’t look like you’ve got any weeds to speak of.” “Just in case,” Tyler said. “You got to stay ahead of the curve on these things.” “All right, then.” Burris tipped his head to signal a friendly end to the conversation. On the driveway, Burris squeezed the basil leaves between his hands, thinking how the leaves themselves were scorpion-shaped, the stems like little tails. He divided the basil among the holes in the bricks, put the other bricks on top, and set them in a row in the sun. In the notebook where he’d kept track of his special corn plant, Burris wrote: Scorpions planted 6/18/2007. Results expected by 6/22. That night, Burris stayed inside his house. Through the open windows came the sounds of the children screaming as they chased the fireflies, smashed the bugs against their skin, and howled in pleasure at the momentary glow. In a pocket of silence between screams, he heard scraps of adult conversation: Poor old guy. Wife died, all alone. Probably glad to have some kids around out here in the middle of nowhere— They were discussing him, Burris realized. He moved away from the window. Glad to have kids around? Running through his cornfield, smashing his plants? The neighbors had no idea—no idea—what they were talking about. Four days after he placed the basil between the bricks, Burris rose at his usual early hour. He fed Zeke, the little bull. Heading toward the driveway, he felt the familiar trepidation that had seized him when he’d gone to check on something he wasn’t sure would work out or not: Did the storm he’d heard during the night drop longed-for rain on the garden, or had hail pellets fallen and pulverized the strawberries? Did the cow successfully birth the calf in the early hours of the morning, or would he find both creatures dead in the barn? On the driveway, Burris looked down. In the beams of the rising 10 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown sun, he saw movement: small scorpions, the color of damp earth, crawled around the bricks. He took note of the scorpions’ heavy front claws, sharp tails that curled jauntily over their backs. Fifteen or twenty of them milled around on the driveway; a couple began moving purposely through his front lawn, headed toward Emerald City. How Mary would have laughed when he told her what he’d accomplished! The scorpions marched through Emerald City. They nestled under rose bushes; a few adventurous ones managed to get themselves up on deck railings. The younger children were initially wary of the insects—which were, after all, frightening-looking, with their huge claws and the pointed stinger at the ends of their tails—but then, when night fell, the scorpions glowed faintly, sending off light from under bushes or their perches on decks. The glowing, of course, reminded the children of fireflies, and so they went after the scorpions to capture them, smash them as they had smashed the fireflies, and rub the luminescence against their skin. It was a little after dusk when Burris heard the first child scream. Another child cried out, and another, a whole pack of howling. Parental voices rose in the dark: My god, look at his face! Look at her hand! What happened? What were you doing, picking up that dangerous bug? The scorpions stopped the children from bothering the fireflies. A few of the children quit going outside entirely; they’d see a row of scorpions on the deck railing, swishing their tails like angry cats, clacking their front claws together like women holding castanets, and even after their parents swept off the little devils with a broom, the children stayed inside to play video games, content with the light of artificial explosions. The corn was safe, though Burris didn’t have the heart to select another stalk to monitor for growth. Next year, he thought. He sat on his stoop and watched the fireflies. With the children inside, the parents’ voices seemed subdued; Burris could almost pretend they weren’t there. He wondered if he’d overreacted to the children’s behavior. He found himself nudged with guilt. When his spinach ripened at the end of June, Burris picked handfuls and left bunches on the front porches of Tyler and Taylor and Tanner, a little offering to make amends.

Crab Orchard Review

u 11

Amy Knox Brown On the Fourth of July, an explosion woke Burris before dawn. A patter of racket erupted; Burris initially thought gunfire before he remembered the date, a holiday marked by sanctioned explosions. He sighed and climbed out of bed. He poured kibble in the kitten’s bowl, then trudged out to the barn to feed Zeke, who cowered in a corner of the stall, eyes rolling in fright. By noon, all the neighbors had come outside. Firecrackers popped, bottle rockets whined and banged, sparklers sizzled and snapped. The relentless noise grew louder as the day progressed. The kitten hid under the bed. Dusk fell, and explosions propelled flowers of fire into the sky. Now and then, someone lit an M-80, and each boom left Burris’ ears ringing. Remnants of cardboard and plastic pattered against the roof like shrapnel. Burris felt as if he was living in a war zone, but told himself that it would be over soon. He went to bed and had actually managed to fall asleep when something tugged at his consciousness. The kitten was standing next to the bed, yowling. Burris opened his eyes. Light smacked against his windows. He heard a sound distinct from the fireworks, a horrible sound of pain. Burris struggled out of slumber. He sat up and shook his head. He realized that the light was fire. He realized the sound of pain was from the bull. One of the bottle rockets must have landed on the barn and set it ablaze. Burris lunged out of bed, his throat dry with horror. He rushed outside. The firemen arrived in time to save part of the barn, but by then the little bull was dead. Burris stood in the half-burned building, looking down at the dark carcass. Water glistened on Zeke’s fur. Even with the sound of fireworks still filling the air, Burris couldn’t get that bellow of pain and fear out of his head. If Mary were here, she’d kneel down next to Zeke and rest her hand on his wet fur and say, Poor little fellow. Burris looked toward Emerald City. In his head, he asked Mary, Henley’s? The hiss of a bottle rocket sounded as if someone replied, “Yes.” In Henley’s, Burris read Virgil’s recipe for bees: Bury a young bull upright, so that its horns protrude from the soil. In nine days, bees will spring from the putrefying flesh. Bees, thought Burris. He leafed through Henley’s until he found the page where Mary had written Works with chicken, too. Her familiar 12 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown handwriting soothed him. He could almost hear her voice, with an undercurrent of merriment: Yes. Bees! The next morning, on the north corner of his property, far from the house, Burris began to dig. It took all day to excavate a hole deep enough to bury Zeke upright. He wrestled the corpse into the grave and left the head protruding above the ground. Taylor (whom Burris had nicknamed Baldy) and Tanner stood on their decks, watching. “That’s too bad about your barn,” Baldy said. He adjusted his ball cap. Burris grunted. “You got insurance to cover it?” Burris shook his head. He shoveled dirt into the grave. “Don’t you need to bury the whole body?” Tanner hollered, though his voice held the tentative note of a city slicker who’d never dealt with death. “This way is better.” Burris eyed them under the bill of his cap. Were they the ones who set his barn on fire? He made eye contact with Tanner, who met his gaze. Baldy casually stared into the distance when Burris looked in his direction. A spent firecracker shell sat on the railing of the deck, and with his index finger, Baldy flicked it off into the grass. Inside, Burris wrote in his notebook: 7/5: Bees expected by 7/14. No rain fell the rest of the week. Temperatures climbed near 100 in the afternoons. Stiff prairie winds carried the scent of the decomposing bull away from Burris’ property and let it hang, instead, over Emerald City. On the ninth morning, Burris rose at his usual early hour. He poured a cupful of kibble in the kitten’s bowl. When he stepped outside, he was greeted with a low hum—a pleasant murmur, like the magnified sound of blood moving through veins. A swarm of bees hovered over Zeke’s grave. It was a thick swarm; Burris estimated four or five hundred bees must have been swirling out of the bull’s corpse. As he watched, a few bees broke from the swarm and headed toward the hollow oak a couple of yards away. A few others buzzed off toward Emerald City. In the hollow oak, the bees made honey. Over in Emerald City, the bees made trouble, buzzing purposely toward glasses of the sweet, urine-colored wine. From his seat on the back stoop, Burris watched the wine-drinking parents swatting the air. Baldy stood on his deck, holding a can of beer, and talking to his wife. Burris heard him say, “Bastard said the stock was going up, up, up and now it’s totally in Crab Orchard Review

u 13

Amy Knox Brown the tank, I don’t even know how much we lost—” and the wife said, “Are you sure?” Baldy removed his ball cap and tossed it on one of the deck chairs. “Of course I’m sure,” he said, angrily. Burris didn’t see the bee land on Baldy’s gleaming scalp, but suddenly Baldy bellowed. “Dammit! Damn wasp!” He pawed at his head, staggering around the deck. Seconds later, he clutched at his throat. He made a gagging noise. Baldy’s wife said, “Now how much did we lose?” Baldy croaked out what sounded like a number: Ninety. Or did he say, “I’m dying?” “It’s just a bee sting,” Mrs. Baldy said. “Don’t be so dramatic.” Anaphylactic reaction, Burris thought. He called out, “You better get him to the doctor.” “What?” Mrs. Baldy said. “He needs a shot,” Burris said. “Go to the hospital.” As it turned out, Baldy’s anaphylactic shock was a mild case. The wife drove him five miles to the emergency room, where a doctor gave him an injection—Burris heard Mrs. Baldy yelling the story to Mrs. Tanner after the Baldies had returned—and the swelling in his throat went down almost immediately. He was inside now, having a beer to restore his nerves. “Damn bees,” Mrs. Baldy said. “I’ve never seen so many of them. I wonder where the hell they came from.” “It’s weird,” said Mrs. Tanner. “I just read an article about the bee population actually going down. Global warming or something.” Mrs. Baldy scoffed. “That’s all a crock.” She paused for so long that Burris glanced over at her yard, and he felt her gaze boring through the darkness, right at him. “I think something else is going on. And you’d better look out,” she added, ominously, turning back to Mrs. Tanner. “I bet you’re next.” The heat wave broke. Rain fell for two weeks. At the end of July, Burris wrote about the weather in a letter to David; he mentioned it to Maggie when she called. “You should come out for a visit,” she said. “Sure,” Burris said. “Pretty busy with the crops right now, though.” “David and I will be out next summer. Get the place in shape, put it on the market. It’s a good time to sell.” Next summer was a problem he could head off when it got closer. “Sure,” Burris said. 14 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown After the phone conversation, Burris went outside to take stock of his garden. The tomatoes had ripened early, and dozens of beans dangled like ornaments off the vines. He found two zucchinis the size of baseball bats hidden under their leaves. He needed to start canning; growing up, he’d helped his mother, then, after he was married, he and Mary spent their annual week in the kitchen, packing tomatoes into jars, cutting beans on the diagonal so they looked like little spears. For comfort, he carried on a conversation with Mary in his head as he moved around the kitchen, getting the canning supplies in order: Where’s the tongs? In the drawer by the sink. Toward the back. There you go. Probably ought to get some new rings for the jars—these ones are sort of rusty. Yes, we should. The next morning, Burris climbed in his truck for the trip to town. Passing the north side of Emerald City—the area that bordered the highway—he noticed a vibrating haze hovering over one of the holes that had been dug for foundations. A swarm of bugs, he figured; the excavation was probably full of water, breeding mosquitos. Two kids stood on the edge of the hole, poking around with sticks. At the hardware store, Burris ran into Dwight, a friend from the grain elevator. They visited about the usual subjects: weather, crop report, The Old Farmer’s Almanac’s predictions for winter snowfall, which was anticipated to be a record. “Sorry about your barn,” Dwight said. Burris said, “I’m pretty sure the bald guy next door was the one that set it on fire.” “Been hearing some things about that Emerald City,” Dwight said. “Oh?” “Heard the developer ran out of money. He can’t afford to build the rest of the houses.” “Huh.” “And there’s lots of insect problems. You had bugs on your place? “No more than usual,” Burris said. When Burris arrived home and let himself in through the unlocked kitchen door, he sensed a slight disturbance in the air, a lingering foreign smell of perfume or cologne, as if someone had been in the house. He berated himself for his foolishness: in his whole life here on County Road 2, there’d never been a reason to lock the door. But now he was surrounded by people he didn’t know. Crab Orchard Review

u 15

Amy Knox Brown He noticed an empty spot in the row of cookbooks. The little notebook where he tracked his corn and later his creatures was missing from the Hoosier. Flour dusted the floor, as if someone had pawed through the flour bin. The hairs rose on the back of Burris’ neck. He drew in a deep breath and realized the foreign odor was chemical, not perfume. He walked into the living room. He saw that the urn containing Mary’s ashes had been moved a few inches on the mantel. The lid, on close inspection, appeared slightly askew. And then Burris saw a fine white coating on the hearth. A substance that looked, from a distance, like flour, but he knew, as he knelt and touched it, that Mary’s urn had been opened, possibly tipped over or shaken, and some of his wife’s ashes had spilled on the hearth. His throat closed with anger. His knees felt nailed to the floor. His fingers, dusted with the cremated remains of Mary’s bones and flesh, shook. A strange buzzing filled his head and spots glittered in front of his eyes. He might have blacked out for a moment—or perhaps even longer than that; when he found himself again capable of conscious thought, he noticed the square of sunlight that had been on the floor directly in front of him had shifted toward the west. Burris drew in a deep, shuddering breath. The buzzing in his head receded. The kitten was sitting next to him. How long had he been there? He looked at Burris with his golden eyes. If he could talk, he could share exactly what had happened while Burris was gone. “You okay?” Burris asked the kitten. The kitten stood, pirouetted, and sat. “Did they come in to steal? Did they take the silver?” The kitten tilted its head. Burris took that as a “no.” “They were just in here to look around?” He felt the kitten’s response pressing into his brain: Something like that. Maybe trying to figure you out. Not meaning any harm? I wouldn’t go that far, the kitten said. Someone came inside his house. Someone stole his notebook and spilled his wife’s ashes from her urn. Burris breathed deeply. He got to his feet, replaced the urn’s lid properly, and slid it back to its original location. The kitten followed Burris to the kitchen. In Henley’s, Burris found Jan Van Helmut’s recipe for mice: If soiled underclothing is placed in the opening of a vessel containing grains of wheat, the reaction of the leaven in the underclothing with fumes 16 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown from the wheat will, after approximately twenty-one days, transform the wheat into mice. Twenty-one days. He needed to start immediately. The half-burned barn seemed like the logical place to grow his mice, though Burris felt a little conspicuous, a little ridiculous, carrying a wide-mouthed vase and a pair of his unwashed boxer shorts across the yard. The shorts were some Mary had given him years earlier for Valentine’s Day, red with white polka dots. Tanner stood on his deck, spraying a can of Raid toward a couple of bees that hovered just out of reach, as if taunting him. Burris had finished setting up his things in the barn when he heard screaming from the direction of Tanner’s property. Two kids— one of Tanner’s sons and Tyler’s son, the initial killer of fireflies—stood in front of Tanner, holding up what appeared to be deflated balloons or scraps of fabric. Tanner was yelling, “Mother of God! Drop that!” “It’s dead, Dad,” his son said. “I just want to know what it is.” Burris moved closer. Tanner covered his face and moaned behind his hands. The kids turned, raising the objects toward Burris. “Do you know, Mister?” the Tyler boy asked. Burris looked through the bottoms of his bifocals. Up close, the objects revealed themselves to be some sort of creature—frogs, Burris guessed. Albino frogs. But then he noticed that the creatures had only three legs, not four; no visible eyes; and their bodies were smooth as Baldy’s head and bloated as ticks. A shiver traveled the length of Burris’ spine. “Where’d you find those?” he asked. “By one of those holes,” the Tanner boy said. “Out by the road.” He offered to hand the creature to Burris, who forced himself to keep from recoiling. “I couldn’t tell you what they are, boys,” he said. “But you might want to put them in the trash, and then wash up real good.” Burris looked at Tanner, who had dropped his hands to his sides. A streak of something white—white as albino frogs, white as flour, white as ashes—striped Tanner’s cheek. Burris waited a week before he checked the wheat. What looked like mold—but was doubtlessly fur—had covered the grains, and they had swelled into triple their original size. July rolled into August. The days grew incrementally shorter. The grains of wheat continued to swell. The fur, originally gray, shifted Crab Orchard Review

u 17

Amy Knox Brown closer to brown. The nights began to hold a warning touch of coolness. Twenty-one days passed, then twenty-five, and then thirty. Burris refused to give up hope. He knew things took longer to grow at the end of the season. On the thirty-first day, Burris found mice in his barn. His creatures appeared slightly different than the gray mice he was used to; Burris’ mice had reddish bodies, spotted with white, and black fur covered their short tails. They were, Burris thought, more attractive than the run-ofthe-mill mice you saw in everyone’s barn. Several of them ventured up to him and sniffed at the toes of his work boots. “Hi, fellas,” Burris said. The mice looked up at him with their golden eyes. They swished their short black tails; and then they crept out of the barn, scampered through Burris’ browning grass, and crossed the lawns of Emerald City. Even before Burris heard stories at the grain elevator, he knew what happened: the mice slipped through barely perceptible cracks in foundations or tiny spaces around windows where the caulk had already shrunk. They climbed inside dresser drawers and gnawed through clothes; they left droppings on kitchen counters. The mice ignored cheese-baited traps. Instead, they chewed their way into cereal boxes and grew fat on Lucky Charms, Count Chocula, and Franken Berry. Burris heard from Dwight that one of the mothers in Emerald City was pouring out cereal when two plump mice dropped into the bowl. “At least she thought they were mice,” Dwight said. “But they looked different than regular mice. They had polka-dotted fur, like some kind of mutant. That was the scariest thing—she wasn’t sure exactly what they were.” The two creatures stood up in the bowl and looked at her, swished their short tails, then hopped off the counter and disappeared while she stood in her kitchen, screaming. Maybe the reason Emerald City was abandoned had nothing to do with Burris, the scorpions, the bees, or the mice. Maybe the homeowners would have fled without any of his doings. There was the economy, for one thing, the lost jobs, the precipitous drop in home values, the spike in gas prices. The houses in Emerald City had been overvalued from the start; by the time the unusually cold winter of 2008 arrived, they were worth less than half of what most people had paid for them. Utilities to heat the high-ceilinged rooms cost a fortune. You had to drive miles and miles to get the most rudimentary groceries, a gallon of milk or a magnum of wine. The contractor had filed for bankruptcy, and so the rest of the development, which had 18 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown been stripped of every growing thing and pocked with holes, presented them with views as barren and malevolent as the surface of the moon. At the end of January—a month of record snowfall: almost four feet—Burris stood next to the propane heater in the grain elevator, listening to reports about the condition of the houses themselves, how they were so poorly constructed that nine months after they were built, they exhibited the trouble you’d expect from a place that had been standing for decades. For instance, a slammed door on the second floor caused the front door to fly open (how was that even possible? Burris wondered). Nails rose out of the deck flooring, and the boards came loose. (Any fool knew you were supposed to use deck screws, not nails, Burris and the other farmers agreed, shaking their heads at the contractor’s ignorance.) Roofs leaked after a hard rain, and the basements flooded. The water in the basement spawned hoards of spiders that somebody had identified as brown recluses. The brown recluses hid in bedclothes and shoes. One woman reported that a spider had dropped down onto her bare stomach while she lay naked in the bath. Burris nodded; he’d heard splashing and shrieking from Baldy’s place a few nights earlier when he’d gone outside to look at the stars. The bites of brown recluses could be lethal. Insecticides, it was said, only made them grow larger. So who wanted to live in a place you could barely afford that was falling down on top of your head, infested with poisonous spiders, on land that spawned mutant mice and amphibians? Well. Burris looked down at his hands and shook his head. He’d had nothing to do with the spiders or frogs. “And some of them are saying your barn’s a hazard, it should be torn down, they didn’t pay money for that kind of view,” Dwight told Burris. “They’re the ones that set it on fire,” Burris said. “I know. The bald one, you said.” “You reap what you sow.” “And he doesn’t like that skeleton of the bull in your yard. He said it gives his kids nightmares.” “You reap what you sow,” Burris said again. “That’s right,” Dwight said. “That’s exactly right.” The neighbors in Emerald City, every one of them, put their houses up for sale. When they received no offers, the families packed their belongings in U-Haul trucks and drove away, leaving scraps of their lives behind—a shoe forgotten in the corner of a closet, a carton of milk Crab Orchard Review

u 19

Amy Knox Brown going sour in the refrigerator, a sleeve of photographs that had slipped down behind a stack of books that nobody was ever going to read. The snow melts. Spring comes. Maggie and David will visit in August, but they’ve given up bothering Burris about putting the farm on the market. “It’s a terrible time to sell,” Maggie admitted during their most recent phone conversation. “Better hold on for awhile.” Mary’s geraniums bloom anew, and Burris drops a few of the blood-colored petals inside the urn on the mantel. He adds strands of hair harvested from her comb. On the eve of the summer solstice, Burris sits on his rear stoop and waits for the first firefly of the season. The scorpions curl under river rocks to sleep. In the hollow of the old oak, the bees kiss and hum. The black cat—who has, oddly enough, shown no interest in any of Burris’ creations—dozes at his feet. No cars pass on the road. No smells of cooking contaminate the air. No human voices, with their tones of hilarity and complaint, can be heard. In Emerald City, the abandoned houses decay, rot an element contained within the boards that age, untended, the process assisted by the relentless prairie wind that blows grit too fine to see, almost too fine to feel against skin, but it does its abrasive work and wears down, eventually, everything it touches. The wind brushes Burris’ face. He lets himself think, Mary’s not dead, she’s in the kitchen. He imagines her standing by the sink, drinking a glass of water. She’s wearing her blue-and-white plaid housedress, white ankle socks, sensible black shoes. She sets the empty glass on the counter and stares through the window at the half-burned barn. She’ll have something to say about that, Burris thinks, smiling. He wonders how long the geranium petals will take to work their magic with the ashes in the urn. Burris shifts in his chair. One of his sweet mice crawls up Burris’ overalled leg, crosses the hand Burris rests on his knee, and creeps along Burris’ arm, tickling his skin with its whiskers. In the corner of his left eye, Burris sees a wink of light. Turning, he sees another light flash on his right side, and he turns again. Moving his head so quickly must be what causes the blue of the sky and the white clouds to blur together so that they look like plaid fabric moving in front of him, the fabric of a dress that surrounds the body of a woman he has thought about every day for the greater part of his life. “Mary?” Burris says. He squints; everything in front of him has blurred. The sky has shifted a 20 u Crab Orchard Review

Amy Knox Brown shade darker. Lights blink crazily on either side of Burris’ vision, and the crickets in the grass go silent. The mouse reaches Burris’ shoulder. It stands and presses its nose gently against Burris’ ear. “Mary?” Burris says again. You’ll see her soon, the mouse whispers. You’ll see her soon.

Crab Orchard Review

u 21

Joy Arbor When God Chose Love over Truth Just outside Bil’in Village, West Bank November 2005 Perhaps it’s that hydraulic excavator on the horizon or what’s left when one world crushes another but here between rows of olive trees, the air is a mouthful of stones. Far from home, we seek the truth but don’t want to speak. The farmer who sees construction dust starve his olive leaves must—the settlement’s expansion steals his harvest, twenty-five dunams of farmland, half the land of the village. No one inhales too deeply. The farmer fingers the leaves. In the distance, the haze of dirt and dust held aloft, the goldenrod of construction equipment, occupation’s infantry of progress. Skid-steer loaders and diggers reroute the earth’s ley lines for indoor plumbing, rearrange veins for sewage retrieval, add more pages for those who long to lie down and rise up in the City of the Book, to dwell all week in Shabbat’s eruv, to tussle with schoolteachers over the value of Nutella sandwiches. Staring out their windows they don’t see the choking olive grove or us, but a blank canvas for flats for their cousins when finally they make aliyah. On the sixth day God chose Love over Truth. Cast out of heaven and down to earth, Truth shattered, crushed diamond facets, fragments strewn everywhere, uncountable. 22 u Crab Orchard Review

Joy Arbor Now there are only truths: partial, incomplete, contradictory. Shards lodged in the lungs, sharp glitter in the sand. We search within and without, on lone mountains, in holy texts, down the throats of strangers and friends. The rabbis say each truth is a door to new realities, new questions. Each threshold must be crossed in turn. In the Palestinian olive grove, truths pelt us from all sides.

Crab Orchard Review

u 23

Roger Bonair-Agard In which Jay-Z asks me to come back to Brooklyn In the dream, me and Jay-Z slapbox like boys do—actually we say it’s okay to throw punches because we believe we can’t really be hurt. We strip down to undershorts. We take our shoes off. I believe I can beat him, but he’s a big dude so I’m a little scared. I don’t want to get caught by a big random punch. You gotta take off those rings, I tell him. He laughs, takes them off. One of them is a graduation ring from my high school. You have a QRC ring?! Yeah pahdnah. I heard about your work. I got one When I filmed that video in Trinidad in 2000. That’s fresh, I say. We start dancing around the room. Jay’s wife shakes her head. It’s not Beyoncé. It’s a local girl he stayed with. They have two kids. We’d been hanging out earlier. She took me to meet Jay. She leaves the room. We flail at each other. No real blows land. Neither of us is going in hard. I’m thinking I need to get inside them long arms so I can hit him with a flurry. I know I can end it quick if I get inside one time—crack him in the jaw. You should take that ring he says. Your fingers is way bigger than mine—paws, I say. We laugh. Jay’s wife is sitting a ways off under a tree, talking to a neighbor—knitting. It’s Brooklyn but not Brooklyn. In another part of the dream I have a frustrating conversation with an ex and then I’m mad I haven’t stuck to my plan to never talk to her again. I’m back with Jay-Z. By now, we abandon the slapbox. We’re breathing heavily and sweating. 24 u Crab Orchard Review

Roger Bonair-Agard It’s time for me to go. We gotta get up I say. No doubt, he says. Come back to Brooklyn fam. We need you. I wish, I answer. I’ve got a kid. Gotta get back to her. Bring her too, he says. Brooklyn take care of y’all. Here’s my number. Gimme a call. We dap up. I hug Jay-Z’s wife. They stand close to each other and wave as I leave. Everyone is a little sad.

Crab Orchard Review

u 25

Shevaun Brannigan Lucky Ones The girls in ripe fruit-bright dresses do not smile their Gulf of Guinea mouths. They have been through the unimaginable ordeal I can’t stop imagining— the girls sleep in rows. They have a busy day ahead. They dream of physics exams, of boys in the village they like, of a disagreement that day between friends. They dream through the cargo trucks pulling up, booted feet descending on their school ground, through guns cocking, through the police fleeing to the bush. Out of the 276 girls kidnapped, at least one dreams she is flying before the men enter the school and begin to yell their God-shouts, to fire their weapons in the air where moments before a girl had been soaring. The girls are herded onto trucks like goats. As the trucks pull away, the burning school collapses into itself like grief, as though the girls are its beams, and without them, the school can’t stay standing. In neighboring villages, as flames spread from roof to roof, so does word of the stolen daughters—like parents’ wails, embers fly to the stars. New constellations.

26 u Crab Orchard Review

Shevaun Brannigan Inside the trucks, the girls huddle together. Some stare out the open back, mark the speed of their lives disappearing with each shrub that rushes past. Then, the trucks begin to slow. Here, my mind falters. To jump from the back of the truck, to risk being shot, to run through the unfamiliar, dark underbrush, to see the flames, to run toward them, to hope that the strangers whose faces are lit by fire can be trusted and can be brave, to risk being chased, to leave their sisters behind? To stay, to risk being shot, to be led at gunpoint through the unfamiliar, dark underbrush, to be told to renounce their God, their life, the laws of physics, to be sold? A girl running toward flames remains running toward flames unless acted upon by an outside force—the woman of the burning village who catches the girl in her arms and tells her she is safe for now. One of the lucky ones. The woman’s body presses against the girl’s. The girl’s body presses back.

Crab Orchard Review

u 27

Andrea Carter Brown Getting Out the Vote after Robert Campin A hard-worn garden complex in Las Vegas. Last stop of a long, desiccating day. Dented door, much painted. Through it, children’s laughter, muted: at least someone is home. Four raps on the brass knocker. A friendly Latino woman opens the door, surprised to find two middle-aged Anglo women. “Grassroots volunteers for the campaign,” they introduce themselves, “We’re looking for,” one consults a clipboard, “Luis Gonzalez.” According to the print-out, he is the only voter living here. “Is he home?” “Yes.” Pause. “Can we speak with him?” “You’ll have to come inside.” Longer pause. “We’re not supposed to.” “He’s paralyzed.” The two volunteers exchange glances, decide to break the rules. Smiling, she leads them down a hall into a small bedroom. In the far corner, a man lies on a single bed. He is wearing nothing but a T-shirt and disposable underpants. In his eyes, a wild expression which subsides only after the young woman, his daughter it turns out, explains who these strangers are. Speaking for him, she tells them: Yes, he wants to vote.

28 u Crab Orchard Review

Andrea Carter Brown No, he isn’t registered. This will be his first election since becoming a citizen, since being paralyzed. Thus, the Q & A begins, the patient daughter switching easily between English and Spanish, as together they complete the complicated form. Citizen: Yes. Over 18: Yes. Name: Last, First, Middle. But he has two last names; they make one the middle. Address: easy. Date of birth: the shocker. How young he is, given how old he looks. Place of birth: Veracruz, Mexico. Driver’s License: No. State Photo ID: to both volunteers’ relief, he has one. The daughter rattles off the number she knows by heart. Signature: their hearts sink, assuming he can’t write. Instead, the daughter squeezes into the space between the wall and the bed, holds the clipboard steady, helps him get a firm grip on the pen, and guides his hand to the slender rectangle within which he must sign. And he does, in cramped, shaky script, legible to the Anglos, who are satisfied it will pass muster. This is one registration they want to get right. May every clerk who lays eyes on it send it on its way without a hitch. May this absentee ballot arrive. In time. En español. May this man, who has waited so long to vote, whose life has been unspeakably hard, be able to cast his first vote for a President

Crab Orchard Review

u 29

Andrea Carter Brown of the “Party of the Poor,” as his daughter enthusiastically volunteers. Five people in that small square room. At the center, a wasted man. On his left, his wife gently strokes his forearm with one finger; on his right, his daughter with children of her own fills in the date. At the foot of the bed, two Anglo women look on reverently, like donors consigned to a side panel or corner of the altarpiece. Humbled, they try not to stare. Instead, unaware until they confess it later to each other, they look at his feet. The nails, especially. So clean, and trimmed. Buffed even. The care that went into that. They take in the room’s cleanliness, the lack of smell, the absence of medical equipment, the second bed for the wife, the man’s bed positioned so he can see out the window. Struggling not to lose it, the Anglo women summon up “Adios”—to the man, his daughter, and the wife, who responds, “Ve con Dios,” using the familiar form of the verb. Giggles, suddenly: unsuspected by the grown-ups, three of the daughter’s children are hiding under the bed. Having heard and understood every word, Spanish and English, in unison they chime in “Good-bye,” a knowing look in their eyes. Long after the two volunteers hurry back to the County Clerk to deliver this voter registration before the deadline, both women

30 u Crab Orchard Review

Andrea Carter Brown will worry about him, will be haunted by the look in his eyes, his wasted legs and dainty feet, will hope this vote brings Luis MartĂn-GonzĂĄlez peace.

Crab Orchard Review

u 31

Cortney Lamar Charleston

“Still Life with Torso of Cornrowed Neo-Soul Sanger” The video rolls: first the chords, and then, there he is; a spotlight skims him from the head down, creating a sheen on chocolate every shea butter believer must praise, and I’m tantalized to the point of hard staring, my bottom lip quivering with a lyric, I think. I’m not old enough for anybody around me to know certainly if I’m straight or not; how to diagnose my eyes’ fixation. I’m still coming into my own, another potential Mandingo bred to drip off the bone and as curious as any swallower of sound and light can possibly be. On the TV: a man, stripped to bare skin. Humanoid drum—a tighthide beat with many a homegirl’s whet-mouthed wanting: this boy, as church-going mamas chide, standing there buck naked, chest all out likely firm enough to dead a punch, abdominals in flex as he sets that falsetto aflutter from his throat like a caged dove. His pelvic bone leads eye lines into a censor-friendly tease at screen bottom; still, a point has been made in that mental darkness. I know what every man has between his legs, but I don’t know exactly what every man has. I know what I have between my own, and what I’d like to, and what a textbook says I’m going to get that I didn’t ask for. I know soul music comes from the pit of the stomach; my soul lived before my body had a name. It whispers prayer that a coffee-colored woman flours the bird of my spirit with lenient hands: call it a nappy headed dream, call it a pitied-fool’s fallacy—unless I twisted my roots. Maybe if I had them tilled, split like a cotton field into rows, if I could really sang like chicken grease in a cast iron skillet or was a prime cut of meat and mystery, then she would come to me, take me with her into a humbler past, our sincerest luxury our closeness when sleeping. 32 u Crab Orchard Review

Cortney Lamar Charleston Yeah, I’m old enough to know no black boy should ever want to travel backwards in time, but I recognize love is strange voodoo; there’s no other way to explain the pin needles, how anatomies of mine move of a shadow mind at the fathom of even holding her—I’m telling you, this is how it feels: like I’m a man with hands, like I’m a man with a mouth.

Crab Orchard Review

u 33

Susanna Childress Ten Long Weeks at Sea The search continues for Architeuthis… —July 2001 And how does the giant squid pull in its prey, with talon-tongue, its radula, its purple mouth spread for vivisection? Scientists wander the deep in pods, pressure-sensitive cameras winking. Let’s roll, they say, We’ve got squiddage—so much time, like everything else, spent waiting for the right time—Today’s the day! Each day you check for blood, for spotting, for the baby to signal, I’m here. I’ll stay. Over the deep-sea CB someone shouts, Topside to Squidrover sudden storm blowing in a real doozie pull up repeat pull up over. No one can tell you how many babies you’ll have to lose. No one wants to speculate. Some mouth somewhere is open. Some beautiful depth, plumbed. In the black of 2000-feet, fish-flecked, the camera delivers silence, the whites of eyes, the path of hands flinging up. 34 u Crab Orchard Review

Megan Giddings I Invented Longing It’s late June and we’ve spent hours drinking blonde sangria in the backyard. Everyone else is in the party, sweating and dancing and having to yell to be understood. We’re in a long talk about whether or not eating the grapes floating in our drinks will make us more or less drunk. More, we decide. Then I talk about how handsome Magneto was. How sexy he made Nazi-hunting. It’s a relief that you finally see my point. When we were in the theater, I gasped the first time I saw him. It was as if his perfectly clinging white polo shirt could turn water into wine. A man behind us had heard me gasp and said, “Get it, Girl.” You teased me about it for days. But now, we vow to quit our jobs, buy dramatic face-framing hats, and travel the world hunting down dictators and fascists. We’re going to live a real Magneto lifestyle. I’m so happy, I swear even my mitochondria are beaming. For months, I have wanted to be with you. And now here we are planning an adventurous life together filled with great clothes and socially condoned violence. And when that life is fully planned, we fall into a conversation about how we’re living in the sexiest time in all of history. At least in the United States. “We’ve invented jeans that make our asses, all asses look great. You can be 500 pounds and still have a great ass,” you say. “Do you mean skinny jeans?” I ask, fishing a grape out of my glass. I pop it in my mouth, feel it burst between my teeth. You nod. The sides of our hands are touching. “Even our superhero movies are so sexy now,” I add. “Growing up, I saw nothing sexy in the Superman movies or Michael Keaton being a wistful Batman. But here I am. An adult woman getting to see Batman do shirtless push-ups.” You tell me about a time before I knew you. The police found a man waiting for you by the dumpster. Well, anyone in my building, you clarify. He was clutching a knife, planning to slit someone’s throat and take all their stuff. Crab Orchard Review

u 35

Megan Giddings You take a long blast of sangria. I watch your Adam’s apple bob with the effort. One of the hardest things, I think, is knowing the right way to say you are precious to me. I’m not sure why I feel this way, but if everything were little—not just my feelings, but the entire world—it would be so much easier to be sincere. “It happens,” you say as if you had just been talking about spilling a glass of water or leaving the grocery store without getting eggs. We lie down. The soil is cool. It’s too bright to see any stars. My mouth is still knit shut. I listen to you breathe and hope my nose is inhaling your exhales.

36 u Crab Orchard Review

Linda Downing Miller The Decider There