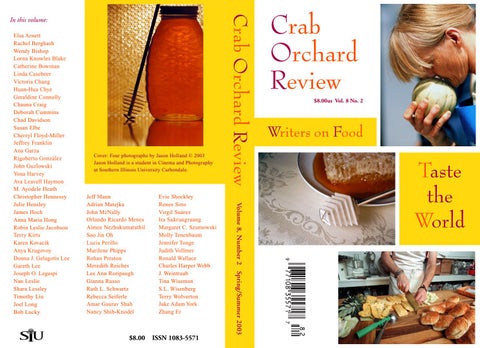

Cover: Four photographs by Jason Holland © 2003 Jason Holland is a student in Cinema and Photography at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Writers on Food

Taste the World

7

82

ISSN 1083-5571

$8.00us Vol. 8 No. 2

77108 3 5 5 7 1

$8.00

Evie Shockley Renee Soto Virgil Suárez Ira Sukrungruang Margaret C. Szumowski Molly Tenenbaum Jennifer Tonge Judith Vollmer Ronald Wallace Charles Harper Webb J. Weintraub Tina Wiseman S.L. Wisenberg Terry Wolverton Jake Adam York Zhang Er

Crab Orchard Review

9

Jeff Mann Adrian Matejka John McNally Orlando Ricardo Menes Aimee Nezhukumatathil Soo Jin Oh Lucia Perillo Marilene Phipps Rohan Preston Meredith Reiches Lee Ann Roripaugh Gianna Russo Ruth L. Schwartz Rebecca Seiferle Amar Gaurav Shah Nancy Shih-Knodel

Volume 8, Number 2 Spring/Summer 2003

Elsa Arnett Rachel Berghash Wendy Bishop Lorna Knowles Blake Catherine Bowman Linda Casebeer Victoria Chang Huan-Hua Chye Geraldine Connolly Chauna Craig Deborah Cummins Chad Davidson Susan Elbe Cherryl Floyd-Miller Jeffrey Franklin Ana Garza Rigoberto González John Guzlowski Yona Harvey Ava Leavell Haymon M. Ayodele Heath Christopher Hennessy Julie Hensley James Hoch Anna Maria Hong Robin Leslie Jacobson Terry Kirts Karen Kovacik Anya Krugovoy Donna J. Gelagotis Lee Gareth Lee Joseph O. Legaspi Nan Leslie Shara Lessley Timothy Liu Joel Long Bob Lucky

Crab Orchard Review

In this volume:

A B ORCH A R R C D •

•

REVIEW

C RAB •

ORCH A R D •

REVIEW A JOURNAL OF CREATIVE WORKS

VOL. 8 NO. 2

“Hidden everywhere, a myriad leather seed-cases lie in wait . . .” —“Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” Thomas Kinsella Editor & Poetry Editor Allison Joseph

Founding Editor Richard Peterson

Prose Editor Carolyn Alessio

Managing Editor Jon Tribble

Editorial Interns Anne Clarkin Barbara Eidlin Reagan Hanley Keith McElmurry Kevin McKelvey Emily Ostendorf Steve Sawyer Crystal Schroeder Mark Vannier Courtney Wilson Jason Vaughan

Assistant Editors Tabaré Alvarez Curtis Crisler Melanie Dusseau Melanie Martin Mary Stepp Krista Marie Vondras Fred Von Drasek

Book Review Editor Jon Tribble

Spring/Summer 2003 ISSN 1083-5571

Board of Advisors Ellen Gilchrist Charles Johnson Rodney Jones Thomas Kinsella Richard Russo

The Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Address all correspondence to: CRAB ORCHARD REVIEW Southern Illinois University Carbondale Carbondale, Illinois 62901-4503 Crab Orchard Review (ISSN 1083-5571) is published twice a year by the Department of English, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Subscription rates in the United States for individuals are $15 for one year, $25 for two years, $35 for three years; foreign rates for individuals are, respectively, $20, $35, and $50. Subscription rates for institutions are $16 for one year, $32 for two years, and $48 for three years; foreign rates for institutions are, respectively, $21, $42, and $63. Single issues are $8 (please include an additional $3 for international orders). Copies not received will be replaced without charge if notice of nonreceipt is given within four months of publication. Six weeks notice required for change of address. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Crab Orchard Review, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, Illinois 62901-4503. Crab Orchard Review considers submissions from January through April, and September through November of each year. All editorial submissions and queries must be accompanied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Please notify the editors of simultaneous submission. Crab Orchard Review accepts no responsibility for unsolicited submissions and will not enter into correspondence about their loss or delay. Copyright © 2003 Crab Orchard Review Permission to reprint materials from this journal remains the decision of the authors. We request Crab Orchard Review be credited with initial publication. The publication of Crab Orchard Review is made possible with support from the Chancellor, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Department of English of Southern Illinois University Carbondale; and through generous private and corporate donations. Lines from Thomas Kinsella’s poem “Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” are reprinted from Thomas Kinsella: Poems 1956-1973 (North Carolina: Wake Forest University Press, 1979) and appear by permission of the author. Crab Orchard Review is indexed in Index of American Periodical Verse. Visit Crab Orchard Review’s website:

<http://www.siu.edu/~crborchd/>.

Crab Orchard Review and its staff wish to thank these supporters for their generous contributions, aid, expertise, and encouragement:

Rick Stetter, Susan H. Wilson, Karl Kageff, Barb Martin, Larry Townsend, Jane Carlson, Kyle Lake, and Jonathan Haupt of SIU Press Division of Continuing Education SIU Alumni Association The Graduate School College of Liberal Arts The Office of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost The Southern Illinois Writers Guild

This issue is partially funded by the Illinois Arts Council.

Crab Orchard Review wishes to express its special thanks to our generous Charter Members, Patrons, Donors, and Supporting Subscribers listed on the following page whose contributions make the publication of this journal possible. We invite new Charter Members ($250 or more), Patrons ($100), Donors ($50), and Supporting Subscribers ($25) to join us. Supporting Subscribers receive a one-year subscription; Donors receive a two-year subscription; Patrons receive a three-year subscription; and Charter Members receive a lifetime subscription. Address all contributions to Crab Orchard Review, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, Illinois 62901-4503.

CHARTER MEMBERS Edward Brunner & Jane Cogie Dwayne Dickerson Jack Dyer Joan Ferrell John Guyon John M. Howell

Richard Jurek Greg & Peggy Legan Beth L. Mohlenbrock Jane I. Montgomery Ruth E. Oleson Peggy Shumaker

PATRONS Alejandro Cรกceres Siobhan Fallon Kent Haruf Jesse Lee Kercheval Lisa J. McClure

Lillian Peterson Eugenie & Roger Robinson Betty & Ray Tribble David & Laura Tribble Clarisse Zimra

DONORS Lorna Blake Tawanna R. Brown Linda L. Casebeer Charles Fanning Jewell A. Friend John & Nancy Jackson Reamy Jansen Rob & Melissa Jensen

Ted & Elisabeth Luther Jeremy Manier Ann-Janine Morey Anita Riedinger Angela Rubin Hans H. Rudnick William E. Simeone Lissa Winstanley

SUPPORTING SUBSCRIBERS Serge & Joan Alessio Joanna Christopher K. K. Collins Jeremiah K. Durick Corrine Frisch John & Robin Haller Karen Hunsaker Chris Kelsey

Lee Lever Jessica Maich Charlotte McLeod Peggy & Albert Melone Nadia Reimer Catherine Rudnick Peter Rutkoff Paul & Lisa Von Drasek

C RAB •

ORCH A R D •

REVIEW

SPRING/SUMMER 2003

VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2

FICTION AND PROSE Chauna Craig

To Taste

1

Julie Hensley

Bread Pudding

3

Nan Leslie

Chez Noir

42

John McNally

Duke’s

52

Orlando Ricardo Menes

Squid

55

Marilene Phipps

Meat

79

Ira Sukrungruang

The Man with the Buddha Heads

85

Tina Wiseman

Sucking on Figs

121

Terry Wolverton

Breath

130

Rachel Berghash

Vignettes from Without a River or Sea: A Memoir

169

Wendy Bishop

How One Food Leads to Another —A Recipe from Memory

178

Rigoberto González

Piña

219

Bob Lucky

Confessions of a Kaya Eater

224

J. Weintraub

My Mother’s Recipes

233

Book Reviews

Recent Titles by Martha Ronk, Adrianne Kalfopoulou, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and Anthologies of Writing about Food and Culture by Italian American Women Writers and on Southern Food Writing

243

POETRY Elsa Arnett

Thousand Years

16

Lorna Knowles Blake

Dulce de Leche King Sugar

17 18

Catherine Bowman

Little Feasts

20

Linda Casebeer

The Object of Desire

21

Victoria Chang

KitchenAid Epicurean Stand Mixer Dragon Inn

23 24

Huan-Hua Chye

In France fourteen and skinny Bog Town

26 27

Geraldine Connolly

Morel Hunting Lost Summer House Blue Ware

30 31 32

Deborah Cummins

The Season’s First Apples

34

Chad Davidson

Truffle Strozzapreti Bread Ossi di Morto

35 37 38 40

Susan Elbe

Fish Fry at Harry’s Tap

59

Cherryl Floyd-Miller

Weaned: Breaking the habit of pork

61

Jeffrey Franklin

Cookin’ with the David Jones Trio

63

Ana Garza

Eating Cactus from a Jar

66

John Guzlowski

Hunger in the Labor Camps

67

Yona Harvey

Blessing Blue Crabs

71

Ava Leavell Haymon

The Witch Has Told You a Story

72

M. Ayodele Heath

The Dreamlife of Dr. Bledsoe’s Inner Pickaninny

73

Christopher Hennessy

Pear, Apple, Peach Meat

74 76

James Hoch

Snapper

78

Anna Maria Hong

Song and Steam Poem about Sushi

100 102

Robin Leslie Jacobson Red Pear

104

Terry Kirts

Eating Ortalons

105

Karen Kovacik

Song of the Sexy Kitchen Saints

106

Anya Krugovoy

Poppy Seeds French Toast

108 110

Donna J. Gelagotis Lee

Journey for the Bread

111

Gareth Lee

Durian Gizzards Ice Kacang

113 114 116

Joseph O. Legaspi

The Red Sweater

118

Shara Lessley

The Pomegranate

119

Joel Long

Preparing the Artichoke

120

Jeff Mann

Galatoire’s

142

Adrian Matejka

Con Leche Not Enough Bread in the World

144 145

Aimee Nezhukumatathil Why I Crave Ribs Tonight Are You Making Dumb Cake?

146 147

Soo Jin Oh

Returning

148

Lucia Perillo

Nathan’s A Simple Campsong

150 152

Rohan Preston

Daily Bread

154

Meredith Reiches

Balducci’s, Greenwich Village

156

Lee Ann Roripaugh

Luscious Things

158

Gianna Russo

Three Feasts in Florence

161

Ruth L. Schwartz

Ripe Fig Apples Tangerine

164 165 166

Rebecca Seiferle

The Anecdote

167

Amar Gaurav Shah

Ode to Bombay Duck

188

Nancy Shih-Knodel

Making Dumplings

190

Evie Shockley

party of two

192

Renee Soto

Martín Palm Sunday Morning

194 195

Virgil Suárez

The Essence of Cardamom

196

Margaret C. Szumowski La Fiorentina

198

Molly Tenenbaum

Year of the Myriad French Bakeries 200

Jennifer Tonge

The Mexican Cooks Return The Bursa Peach

202 204

Judith Vollmer

The Coffee Line

205

Ronald Wallace

Hamburger Heaven

206

Charles Harper Webb

After Thirty Years, I Meet My Highschool Sweetheart in the Cookbook Section at Safeway

208

S.L. Wisenberg

In Restaurants

210

Jake Adam York

Fire To the Unconverted Pilgrimage

212 214 216

Zhang Er translated by Timothy Liu

Watermelon Juice

217

Contributors’ Notes

256

INDEX TO VOLUME EIGHT — 2002/2003 INDEX OF BOOK REVIEWS — 1997/2003

267 278

A Note on Our Cover The four photographs on the cover of this issue are the work of Jason Holland, a freelance photographer and a student in Cinema and Photography at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. The photograph on the back cover and the middle photograph on the front cover feature a honeydipper created by Edna Madera Matejka, a graduate of Southern Illinois University Carbondaleâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s School of Art and Design and a winner of a Rickert-Ziebold award in 2001 for her work in metalsmithing. She is currently working on her MFA in the Metals Department of the School for American Crafts at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Chauna Craig

To Taste

The baker’s daughter steals her daily bread, tucking rolls and warm crusts in her skirt. She nibbles these as she walks to school some misty mornings. Sourdough is for the sea, for boats to weather any storm and gulls to guide her home. Honey wheat is for the plains, the dirt she would plough, the farmer’s wife she could be. The croissants are for Paris, for silver jets and open-air cafés, for the way she will let strangers kiss her. Her pockets, stained with butter, become translucent as the skin of saints. She grows fat on bread, her arms resembling loaves tucked and pinched and rising up out of the pan. Her mother complains, what boy will love you now? She moves the butter, hides the cheese, forbids whole milk, and locks up the cakes. The baker’s daughter simply smiles, shaking out the telltale crumbs on her return so the sparrows can imagine they’re gulls, so the starlings can dive with the red-tailed hawks. One day while she lets Paris melt in her mouth, tasting joie de vivre on her tongue, she steps into a city street and the milk truck can’t stop. Her spirit rises like good yeast, and a grackle steals the bread that falls cold from her hand. The milkman is horrified, the mother distraught, and the baker throws his starter doughs into the trash. A starving woman rooting for a meal will find it and eat it and feel her stomach expand with cramps for days. The milkman brings to the silent bakery bottles of milk, their necks clogged with cream thick and white as snow. He begs them to taste. His eyes fill with tears, and while the baker turns away to dismantle his mixer, his oven, his life, his wife stretches her finger and takes a small taste. Each day the milkman returns. Each day she drinks more until one morning she gulps a whole bottle and milk spills down her chin and onto her breast where it stains and sours by nightfall. The baker tells her to throw away that dress that smells like the infant their Crab Orchard Review ◆ 1

Chauna Craig

daughter once was. But his wife wears the dress to bed and in the morning when the new milk comes. Their bed begins to stink. She grows fat with milk. Her breasts swell and her hips round as they did when she was with child. The milkman sees how lovely she is, milkfed. He imagines her on his dairy farm, kneading bread and feeding children, lots of plump, healthy children. And because her fingers still remember the roll of dough and her breasts the pull of milk, she buys a new dress, white as cream, silky as flour. After the baker leaves, she weds the milkman, they honeymoon in Paris, and they raise their babies on whole milk and cheese and buttery croissants. One winter day, when a thin man steals from their trash a crust of bread, he will chew it slowly and recognize the taste. He will imagine he is a sailor facing the salty spray or a farmer cutting the earth. Finally, at night, stirring the molding blankets of his bed under the pier, he will remember that once he baked. Once he made everything rise.

2 â&#x2014;&#x2020; Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

Bread Pudding

This is not the story of my lover. And neither is it the story of my girls, although both their beginnings are gnarled somewhere in the thick of what I’m going to tell you. This is my husband’s story because I label it so. I have never told my daughters, but I suspect if I could tell it to them—tell it the way it happened and the way it plays out in my mind—they would say it is first my story. More than once my girls and I have packed a lunch and driven into the hollow, have climbed the washed-out logging trail that twists up to Cedar Creek Falls, and have had a picnic there amidst the ruins of an old farmstead. You can see, if you know where to look, the foundation of a cabin and the ruins of a family cemetery, limestone grave markers covered in nettle and moss. Between the two, we’ve found tangled pumpkin vines, the remnants of an abandoned garden, flowering yellow in early summer. The plants continue to grow without reseeding or direct sunlight, even after more than eighty years have passed. That is the way it is with this story. I am allowed my secret. We all move around it carefully, knowingly. It grows larger and greener like the grass the cows leave untouched around last year’s manure. The people I love radiate out from a season of loss. The summer of my fifth wedding anniversary was the driest in forty years. By July, the corn still hadn’t risen past the fence posts. The leaves pulled away from the stalks, shriveled, and curled toward the ground. My husband Neil, who planted only about twenty acres of corn, grew it mostly for silage. But each week I would fill the back of the International with the best ears. This was in the time before the trees bore fruit, when my mother and I ran a roadside vegetable stand on summer weekends. I was strong then, and I would move down the rows with ease, cradling the crates of corn against my hip, sending the contents rumbling into the truck bed when I reached the end of a row. Cora, from the time she could walk, would Crab Orchard Review ◆ 3

Julie Hensley

sit in the shade of the tailgate sifting dirt through her fingers and sorting the pebbles into meaningful piles. That year, instead of the quiet sigh of summer, the field was a hollow rattle around me. Forest fires were burning on the backside of Old Rag Mountain, and although the sky thickened gray in the afternoon, it was only ash hanging in the air, Neil worried for the fruit trees. The young orchard, which in ten years was to be our primary income, might not recover. Twice he filled five-gallon buckets from the pump by the barn and drove—with water sloshing over the sides of the truck—through the lines of new trees, pouring carefully around the base of each one. Neil brought home the fire truck and the man the same morning in July. The truck was already an antique, a 1934 American La Franc. Its red paint had faded to orange, and the words Shenandoah Hose Company stretched in a faded arc along each door. The cab was an open cockpit. Coiled in back were flat, gray loops of hose. Rosario, who was short and thick, and all hands and shoulders, was to be the night irrigator. His hair was slicked back with water. It looked dark and clean in a way that reminded me of the old-fashioned men of my girlhood, my father and his friends milling around outside church. His skin was brown and mottled like pecan shells. Rosario refused dinner, so when the rest of us gathered beneath the grape arbor, lawn chairs pulled up to the oak slab table, Neil told the man’s story for him. Bees murmured overhead even though the grapes were small and hard from the lack of rain. “He’s originally from Chiapas,” said Neil as he took the plate of cold chicken from my mother, “but he’s lived in the States since he was nine. He says his people just kept working and moving. He and his brothers crossed over inside a crate beneath a truckload of melons. Christ, it makes you realize how easy you got it, don’t it?” Cora was seated in his lap, and he had to pull her hands away from his tea. He gave her the cup with her milk, the one with dancing rabbits. “Does he speak English?” Dad wanted to know. “Sure,” said Neil. “He’s spent the last few years doing irrigation work out in California and Arizona.” “There’s a good many of our boys looking for work right here.” Dad was right. Young vets, only recently returned, hung around on the sidewalk in front of High’s Dairy Mart. Sometimes they waited 4 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

with backpacks and cardboard signs along Route 33, thumbs extended in the wake of wind and horn from the rattling poultry trucks. “Well, this one made himself known to me.” My husband tore pieces of chicken from the bone and handed them to Cora, waving the flies away from their plate. He no longer worried about pleasing my father. “He saw me looking over the hoses, and he told me that he could rig up a pump and have the whole works going in two days.” “Where are we going to put him?” asked my mother. The farmhouse already felt crowded. The only bedroom not in use was cluttered with boxes of seasonal clothes and holiday decorations. Her sewing machine was arranged there on a folding card table. In the end Neil cleared out the tack room, and Rosario settled in the barn. When I was a girl, things grew differently. We never had to wait for rain. Nearly every evening, summer storms shook the darkened window frames and, for a moment, bathed the barn yard in blue light. Each morning, the ground was sprinkled with small branches and feathery leaves from the walnut trees. This entire valley is a flood plain for Dry River, and several creeks come down out of the hollow, forking like lightning across our pastures. When my grandfather began farming this land, he had to build ditches and place drainage tiles beneath the earth to diffuse some of the ground water. He planted all sorts of things—soybeans, corn, wheat, barley, sorghum, milo. That way he could expect something to grow, regardless of the weather. He crossed the farm with barbed wire fences, partitioning it into several acre plots. By my girlhood, the wind had seeded each fence row with cedar scrub, blackberry bushes, and skunk weed. I tore up my legs following my brothers through that mess of bramble, searching for the snakes and field mice that teemed there. When my father took over, he, like everyone else, began to rely more heavily on corn, selling it for chicken and turkey feed. Long houses for poultry had begun to appear all over the valley. We could see so many of them from the ridge at night, narrow strands of light in rows three or four deep behind the twinkling farmhouses. Some farmers began removing the fences and planting fields of corn so massive they worried that children would become lost in the canopied rows. But we played hide and seek beneath the flutter of green light and insect wings. I can remember kneeling, breathless, in the silt and looking up through the layers of leaves to where the sun winked white and far away. Crab Orchard Review ◆ 5

Julie Hensley

Neil and I changed the face of the land yet again. We grazed several dozen head of cattle where the largest creek drained into a pond; although, that summer it had shrunk to a third its normal size and was covered in a gray-green scum. Every year, Neil ordered fifty more fruit trees—mostly Stamens—to plant on the east side of the farm. They arrived in September in two shipments, the roots of each tree poking through a hulking mound of burlap and crusted soil, and they had to be planted before the first frost. I had no idea there were so many varieties of apples until I read the descriptions off the waxy pages of the Southern Fruit Co-op Catalogue. Dad teased Neil about the trees. “What do you want?” he said when he saw my husband bent over the book, “To be a gentleman farmer?” He was slowing down, and he wanted Neil to take over. But my father wanted things done his way. He didn’t like the fact that Neil had a job at the muffler plant in Garrison. My husband worked a twelve-hour shift three times a week. He came home sweaty and exhausted, his brown hair matted from his hard hat and the creases on the back of his neck etched with metallic dust. My father couldn’t understand why we wouldn’t just stick with corn and farm full-time. My husband grew up fatherless in a row house in Bayonne, New Jersey. He had to think about the land as a gift and keep it separate from the responsibilities he owed Cora and me. If he mixed them up, the blue line of the mountains might creep in and make him feel trapped. He loved his trees too much, but they were also his way of continuing to love me and our daughter. When Neil came in, jeans wet from carrying water, my father always grunted, “How were your darlings?” I had difficulty sleeping that summer. I would lie down with my daughter in her sleigh bed and breathe in her yellow hair. And later I would lie down with Neil. That was the only time he smelled like himself, right before he went to bed, the only time when the scents of work and the farm didn’t hover—the tang of factory grease, the powdery sweet smell of hay, the musk of skunk that hung over the whole place early in the morning. We held each other as the ceiling fan moved the dry air across our bodies, but that was all. I lay in the long curve of his arm and wondered when we had grown this tired. After I’d seen everyone to sleep, I would move back through the dark hallways on bare feet, afraid of waking the others, as much out of selfishness as consideration. 6 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

I baked at night, since it was much too warm to turn on the oven during the day. Rosario’s second night I prepared a cobbler. The apples were store-bought, out of season. As I rinsed the bowls and measuring cups, I stared out into the backyard. Moths fluttered against the window glass. The barn doors were thrown back, and inside, in the quiet, orange glow of an electric lantern, I saw the shadow of Rosario’s back bent over some piece of machinery. I carried a plate of cobbler and the small table fan I used in the kitchen. Underfoot, the grass was dry and prickly, except along the chicken coop where the dogs had run the ground slick. He stopped his work and stood up when I entered. In the dirt and straw sat an engine from an old car, probably one of Dad’s Studebakers. My father drove his cars until they stopped running and paid to have others hauled in. His automotive history hulked between the trees behind the barn, stripped shells of vehicles covered in Kudzu and Virginia creeper. When we went for walks, Cora always wanted to climb across the cracked leather and mildewed upholstery to sit behind the wheel of one of them. “Mrs. Ridenour.” Rosario wiped his palms on his pants. “Call me Helen, please,” I said. “I thought this might make your room more comfortable.” I set the fan down. “And here’s some cobbler.” “Thank you very much,” he said, taking the plate. His words had a sing-song, memorized quality. Taking the fan in his other hand, he turned and stepped up into his room. I heard him pull the string, and a single bulb flickered on overhead. The tack room had a wood floor and an open doorway. Neil had fastened a yellow plastic shower curtain across the entrance, but it was pushed aside and held in place behind a large nail. I hovered on the threshold. They had moved the saddles up to the loft. The shelves had been dusted and the rough floorboards had been mopped, but the smell of saddle oil still lingered. “Would you like to come in?” he asked. I stepped just inside the door. The cot was neatly made with the quilt and sheets I had sent out the day before, and on one wall Neil had hung a small rectangular mirror. The silver had faded away from the back, leaving the edges tarnished. A wooden spool that had once held fence wire had been fashioned into a table in the corner, and it was there that Rosario set the fan and the plate of cobbler. “Are you sure this room will be all right? It’s too hot out here.” A tiny radio and a comb rested on the table, and I could see his Crab Orchard Review ◆ 7

Julie Hensley

empty duffel bag under the cot. I wondered if his clothing and personal items were stacked in the cabinet, the one that was usually cluttered with brushes and fly spray and a pink minty ointment. “We may need to get you another fan, a bigger one.” “No,” he shook his head. “Everything is fine.” “You’re certainly up late,” I said. “When I saw your light I was worried you couldn’t sleep out here in the heat.” “I work at night,” he said. “In the sun, water will burn the leaves of the plants.” That night I returned to the house and was able to fall asleep in Dad’s recliner. The light stayed on in the barn, though, and it was strange to know that someone else glided opposite me in my silent night movement, that we were together orbiting the house and the fields and the sleeping forms upstairs. When I was seventeen, my parents sent me to New York to visit my brother. It was Christmas break, my last year of high school. Dad drove me to D.C., and I took a train from there. My parents purchased the ticket and gave me one hundred and fifty dollars. I hid the money carefully in various pockets and compartments, except for a fifty dollar bill, which Ma sewed, in case of an emergency, into the lining of my wool dress coat. This was a lot of money, particularly in the winter when everything was tightly budgeted. They were hoping that if I could see the city and the life James had there, I would come to my senses. They were offering me the same educational opportunities they had my brothers, and they couldn’t understand why I was refusing them. “Your girlfriends don’t have this kind of chance,” my mother never tired of telling me. She wanted me to go to Hollins College and study to be a teacher. James had purchased a guidebook and a pile of tourist maps, so that I could keep myself busy during the day. He’d made an extra set of keys—one to his apartment, two to enter his building, and one to open the iron gate that closed the steps off from the street. “Maybe you should take the ferry from Battery Park today,” he said. “I hear there’s a awful line on the weekends.” He circled sites on the map with a black felt-tip pen while he drank coffee. “Do you want me to make you some breakfast?” I asked him. “I don’t keep food,” he said. “It just goes bad.” He took some bills from his wallet and tossed them on the table. “Here’s some money,” he said. “Be careful.” 8 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

I watched his departure through the barred window. He took off at a brisk walk, paused to check his watch, then raised his hand to hail a cab. There were things in the apartment I would have to commit to memory to describe for my mother upon my return—the stiff, green leather couch, the refrigerator with the working bulb, the muffled feel of walking over the thick rugs. Her back hurt her so in the car that she could never suffer the train ride up to see these things for herself. But she would be glad to know that her oldest son’s tap water ran in one warm stream. In the kitchen back home we had only cold water, and two faucets had to be adjusted above the tub in the bathroom, one for cold and another for hot. There were other things that would not interest my mother, even though these were the things that clarified most how much my brother had changed: shelves of strange records, with pictures of men who had black, moist skin; a desk littered with open file folders and yellow legal pads half-filled with my brother’s masculine scribble; a rack of dark and ready wine bottles stacked sweet to dry. The only reminder of home hung in his bedroom. Framed in raw wood above James’s bed was an aerial photograph. Everything was gray and a little blurry, but there were the creeks, spreading like blue-black veins beneath the reflective surface of the glass. The ridge of bramble and curling cedars that would one day be our orchard. The house, white and windowless from so far below, its courtyard sprinkled with familiar out-buildings. Perhaps he had commissioned someone local to take it, a crop duster or a patrol pilot during the fire season. When I ventured out and down the block, I paused every so often, checking my handbag for the keys and the map. I told myself, I’d find one thing that day, make my way to one of the little black circles. First I stopped for a late breakfast in a diner not a quarter of a mile away. Over the door a sign said Hot Food. Inside was a small bar, a cash register on one end, and a grill in the back. I sat down on a stool covered with cracking leather. Two men stood in front of the cash register, and the first ordered an egg sandwich to go. The young man behind the counter turned and, using one hand, broke two eggs over the grill. His hair was in a crew cut, and I noticed that his face and neck, even his ears, were covered in freckles. The first man tapped his newspaper on the counter. The eggs Crab Orchard Review ◆ 9

Julie Hensley

sizzled and popped. “Goddamn, you take too long.” He smacked the counter with his free hand, and turned to leave. The freckled man shrugged and sort of smiled at the next man. “What can I get you?” “Two eggs, fried hard, and toast.” Behind the counter, the man reached into an open bag of bread and dealt two slices onto the counter. He brushed them with melted butter and set them next to the eggs on the grill. “I don’t want those eggs. Those were his eggs.” “So, now they’re your eggs,” said the cook. “They’re just eggs.” “I want my own eggs.” They clipped their words in a way that made everything aggressive and experienced. “Suit yourself.” As the man with the freckles reached for two new eggs, the customer said, “Forget it,” and stomped out the door. So I ate four eggs and two pieces of toast and a milkshake for breakfast my first morning in New York, and that’s how I met Neil. I spent every day sitting at that bar. Sometimes I bought a magazine and flipped through it while he saw to customers. Sometimes I just turned and watched the people hurrying by. Frustrated at my lack of adventure, James dragged me into the subway on Saturday morning. We came out of the ground somewhere on Madison Avenue and clomped along the edge of the park, past the town homes, verandahs wrapped with red ribbon and plastic pine boughs. It started to sprinkle. We rode the elevators to the top of the Empire State Building, and I made James put change into the telescope. The city groaned beneath us. The rain came in large, slow splats. “Which way do you live?” “Queens,” he said, pointing. “Across the East River.” I swung in that direction and thought about Neil, grilling pastrami and rye bread. I turned down my husband, inched away from the familiar pressure when, after weeks in that dry embrace, I felt him rise against me. He was not asleep when I left the bed, but he was not angry. Chemical planes hummed overhead, outside. At night, the fires moved in creeping orange down the mountain slope, an eerie volcanic glow. People, according to the radio, had refused to leave their homes. I imagined them, rising every few hours and climbing on top of their houses, inspecting the progress from their glistening rooftops, hoses in hand. 10 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

Rosario turned the cornfield, which Dad insisted was the more immediate loss, into a twenty acre swamp. A new coolness arose from there at night, and you could almost hear the stalks nestling, drinking in the tepid water. He moved up the ridge with the fire hoses, and when they would no longer reach, the night irrigator wooed each tree in careful bucketfuls. I brought banana muffins and crumb cake and warm wheat bread. I carried them in the linen napkins that one of Neil’s aunts had embroidered as a wedding gift, and Rosario unfolded each item carefully, the same way my mother has always unwrapped a present, peeling back the taped edges, setting aside the paper to reuse on some other holiday. He ate what I brought him with a ferocity that made my heart swell. Now, it seems like he was two different people during the month he spent with us. There was the man who rose just in time for lunch, who filled a space at the picnic table and offered polite, yet evasive, answers to Ma’s questions, the Rosario with whom I exchanged everyday pleasantries as I picked up an empty plate or shifted Cora on my hip. “Do you have children of your own,” my mother asked him, “back in Mexico?” “Yes,” he corrected her, “in California.” “How many?” she wanted to know. When he told her a few, she grew insistent, “You should bring them out here. Kids need to be with their daddy.” He smiled and shrugged, and once, when he had left to run some errand for my father, she confided to me, “I don’t really think he understands a word we say.” Then there was the working Rosario, clad in rubber boots and overalls, leaning against the tailgate to pause for a slice of whatever I’d brought him. Never again did we exchange even as many words as we had that first night. I sat in the truck bed, watching him work beneath a series of hazy skies. There were no clouds, but the ash hung on the horizon, giving everything a fuzzy glow. From the top of the ridge the neighbors’ turkey houses, the porch light, even the kitchen window wavered as if underwater. Rosario bent again and again. Mosquitoes hung around his knees, hovering over the fresh mud. He would not allow me to help, but he never sent me home. Sometimes, if I fell asleep in the back of the truck, he would wake me, his hand wet and warm against my bare foot—“Despiértate, Helen. Wake up!”—just as silver light was beginning to glow behind the shadow of Old Rag. Sometimes I woke confused. He would return the napkin, folded neatly, and nod toward Crab Orchard Review ◆ 11

Julie Hensley

the house. I walked back through the mud barefoot and, even before there was anything to hide, rinsed my feet at the pump. On Neil’s days off, the men moved together through the corn rows. The mud sucked at their feet as they fingered the leaves, marveling at how quickly they were softening and unfurling. Neil and I were married, against my father’s wishes, two days after my graduation in a civil service at the Town Hall in Garrison. To be truly blessed, Dad said, a marriage must take place in a church. The minister at Shelby United Methodist refused to perform the ceremony since Neil had already been living with my family for several months. Only my parents witnessed our union. Neither of my brothers returned home. We spent our first night as man and wife at Skyland, the hulking lodge that hugs the mountainside in the middle of the Shenandoah National Park. We ate in the dining room, surrounded by other vacationing couples. It was early in the season, and we were all allowed to linger over our meals. The evening sun came through the picture windows and cast a golden light on the giant chestnut beams that stretched the full length of the ceiling. The thought of leaving that room and walking across the terrace to our tiny cabin tightened my throat. I ordered blackberry ice cream and ate it slowly. I locked myself in the bathroom. I sat on the toilet in my bra and slip, both white and trimmed in lace, far more delicate than my everyday fair. I was seventeen. “Helen, honey, are you all right?” Neil’s knock was careful and hesitant. “Come on out,” he said. “We’ll go for a walk and relax.” It did not happen that night. And when it did happen, days later, on the bed I had slept in since I first started school, we faced each other with a sweet and embarrassed reverence. My grandmother taught me how to make a bread pudding. It’s a recipe that requires a certain amount of patience, and because of that some people can never get the hang of it. The most important thing is the bread. It needs to be a large homemade loaf that has been left uncovered on the counter for at least a day, and you have to tear it into chunks about the size of a man’s thumb. You layer the pieces of bread in a medium greased pan, alternating it with layers of walnuts that have been crushed and shaken with cinnamon and brown sugar. Beat three eggs and add 12 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

almost a cup of sugar. Then mix in four cups of warm whole milk, adding a teaspoon of vanilla and a pinch of salt. Pour that mixture slowly over the layers of bread crumbs and nuts. This is the secret: you set the pan inside another pan in at least an inch of hot water and bake the whole thing at 350 degrees for at least an hour. The key to a good bread pudding is keeping it moist. The steam rises up and replaces what is lost to the heat of the oven. To make it really good, you cream butter and brown sugar and add milk, drop by drop, until you have a sauce the consistency of a good gravy. Once or twice while the pudding is baking, you pour a little of that mixture over it, and then when it has finished, pour on the rest. It’s a messy and decadent dessert, the kind of thing you have to sit down and eat with a spoon. When I made Rosario a bread pudding, I had plenty of time to think about what I was doing. I set the bread out early that morning. Once everyone was asleep and I began tearing the loaf and arranging it in the pan, the process took nearly two more hours. The faucet above the tub screeched horribly whenever we turned the water on, so I crumbled a bar of lilac powder in the sink and sponged off while the dish was cooling. After that night, he always stopped whatever he was doing when he saw me walking up the hill. I liked the fact that with Rosario there were so many questions. He had children out West. Although he never wore a ring, he probably had a wife or at least a girlfriend somewhere. I didn’t want to ask, certainly didn’t want to know the answers. I liked the thickness of the things unsaid between us. Neil and I had always talked, before and lying together for a long time after. We even talked during. In fact, sometimes we talked so much we talked ourselves out of it if one of us was tired or not really responding. That happened right after Cora was born, and again the summer of the drought. Rosario worried that he smelled like sweat and mud, but I didn’t mind. In fact, I thought of it years later when my daughters, visiting from new lives out West, claimed the thing they most missed about the farm was the smell of good dirt. Mama and I were boiling walnut shells and soaking strips of green wood, an end of August ritual. She would weave the materials into baskets to sell at the county fair in the fall. Our fingers were stained an oily, yellow-brown, that nothing but turpentine could remove. We could not touch anything, not even Cora, who whimpered back and forth between each of us in turn. We had let the phone ring Crab Orchard Review ◆ 13

Julie Hensley

all morning because of the mess, but I answered it finally, exasperated, lifting the receiver from the wall with a damp dish towel. “Mrs. Ridenour,” the voice was well-versed in the language and tone of loss. “This morning your husband was involved in an accident, here, at Walker Manufacturing.” “Where is he?” My mother stopped ladling the black mixture, and looked up. I asked, “Is Neil all right?” “Ma’am, I’m sorry, but we have not been updated on Mr. Ridenour’s condition. We only know that his situation was critical. We’ve been trying to reach you for several hours. I suggest you go immediately to Garrison Memorial.” Of course, it was too late. The sleeve of his uniform had caught in his machine, and the blood loss from his mangled arm was massive. Hours later, I signed paperwork in a quiet hospital office. I left brown smudges everywhere my hands settled. Rosario’s departure was unceremonious. He walked to the end of the lane and waited, sitting on his duffel bag in the dust, until a van load of workers stopped to pick him up. They were heading toward Winchester for the fruit harvest. I had no way to reach him and could not yet imagine that I would ever have any reason to. The ears remained on the cornstalks that fall, and the stalks remained standing, unused even for silage. The rains that came the first week in September flooded the creeks, and the Shenandoah threatened the bridge that connected Shelby with the highway. When the smoke cleared on Old Rag, a mean scar of charred forest split the skyline. The corn, which rotted in the field, tried to come back on its own the next spring, but it was choked with crab grass and Queen Anne’s Lace. Not until the next year would Dad plow everything up and reseed it. The storms split a walnut tree, and it tore through the century-old grape arbor, destroying the table underneath. Although the wind shook the gray undersides of the leaves, the new fruit trees held onto the hillside. We scattered Neil’s ashes along the ridge on an Indian summer evening. They returned my husband in too small and too ordinary a box. It looked like it should hold take-out food. Only Cora was unafraid of the soft ash and hollow bits of bone. She trotted across the damp hillside, releasing her father into the breeze, her fingers spread in her own quiet vesper, an early sliver of moon hanging in the blue over her shoulder. We called a local collector to come haul 14 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Julie Hensley

away the fire engine, and then we retreated into the house for an entire season. Outside, though, the days pressed on around us. To make sense of things, I tried to find the rhythms that had previously moved my life forward. I kneaded bread, I canned tomatoes, I hung sheets on the clothesline. And when solace failed to rise up out of my old rituals, I sought new ones—scalding baths, doses of mineral oil, hours chopping wood—hoping to work the secret out of my system before anyone could notice the change. But the truth has a way of taking root, and she clung there, like a sunken apple inside me, determined to find her way to the sunlight.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 15

Elsa Arnett

Thousand Years

She passes on none of this: A dozen duck eggs. Two cups strong oolong tea. From the edge of my biochemistry text, I sneak a glimpse. I cannot cut flank steak on the grain; cannot smash a garlic clove with the side of a butcher’s knife. No man will ever throw a potato pancake at you because it was too soggy. Salt, in a cup, up to her second knuckle. Late night, she brings lotus-seed sesame balls to my desk, my head a convolution of theorems, declensions. One cup fresh-squeezed lime juice. She fills my lunch bag with sticky rice, dried cuttlefish, the awareness that promises are perishable as late autumn persimmons. This is the tricky part: two cups ashes of pine wood, two cups ashes of charcoal, two cups fireplace ashes. I don’t ask anymore about the lacquer box in her closet, smothered beneath flannel blankets: boar bristle brushes, black ink stone, scroll paper delicate as the veined wing of the damselfly. Her palms are pocked by oil splatters, fingertips patinaed from turmeric. Combine tea, salt, lime, ashes. Coat each egg with paste. You will never be stuck on a corner with grocery bags for a ride that does not come. Line ceramic crock with red earth. Insert encrusted eggs. Bury into soil. Ferment 100 days. All those nights she waited for his phone call from far-flung locales, the line crackling like hot chilies in a wok. She doesn’t tell me this, but I know: expectations crumble like stale rice paper. Dig up crock. Rinse eggs under warm water. He said nothing when he saw the jar of black beans overflow, a bottomless gorge she tripped into while walking in her sleep. Crack browned shell, peel. Cut into quarter-moon slivers. The white of the egg will become a gelatinous black amber, the yolk, a phosphorescent green; both transformed completely from what they were.

16 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Lorna Knowles Blake

Dulce de Leche

Ahead of us a man asks for his coffee extra light, fuel for the dark midwinter. The frozen food case is heating up—lime sorbet, mango madness, passion fruit glacé. In the fogged glass my mother blooms briefly, wearing a flowered shirtwaist dress in a tiled kitchen slick with island heat, late morning moistened by the steam rising from pots filled with boiling cans of condensed milk—she must be making the caramel paste we loved to spread on toast, slices of fruit, our fingers. And tonight in a Broadway deli, rows of crystal-crusted lids announce a new exotic flavor of premium ice cream— Dulce de Leche sighs the Scandinavian label on the pint we carry home. What does it mean? my daughter asks. Sweetness of milk or milk candy, I tell her and the words melt away like memories, lost in translation.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 17

Lorna Knowles Blake

King Sugar

Sugar cane harvest: an arc of machetes scythes down, decapitated stalks fall like soldiers crossed on the fields. The smell rises in the heat, so sweet the air itself sickens. The cañaveral is full of spiders and armies of men in straw hats, shaded faces, backs burnished to mahogany, advancing like a wave in an unbroken rhythm over the fields of cane. Later carts of cane are refined into sugar and fire ripples over the stubble of roots, incinerating the land, leaving a wake of black remnants glowing in the cremated fields. Clouds of black ash drift over the town. We dust and clean, black snow keeps falling. Dust and clean and dust— 18 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Lorna Knowles Blake

It’s positively biblical, you say, the burning fields, ash falling like a plague— or a sign to remind us how we burn for that pure white sweetness at the core.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 19

Catherine Bowman

Little Feasts Loving you is like eating bread dipped in salt. —Nazim Hikmet Like juice lemons pickled on the new moon, serpent garlic, slowcooked, spread on a bed of greens, packed in cheap coastal salt, stir-fried, stewed, seared, sweet soy, a well-flavored stock, deep-fried with a tartar of malt vinegar, battered in brown ale, plain flour and an egg, blocks of compressed tamarind, soaked and mashed, curried leftovers, caramelized, fried fish in salsa verde, wild fennel, parsley, étouffée smothered in its own juices, jack and pompano, mango and spring onion, coriander, lime leaves, ginger root, mackerel, clam hash, oyster beds, catfish in buttermilk and cornmeal, mole negro, almonds, ground cloves, cinnamon, savory pastries, skillet snapper, a rub of paprika and cayenne. Gulf coast gumbo for meatless Fridays. Paella de campo eaten straight from the pan with the first three fingers of the right hand. Sweet orange. Bitter chicory.

20 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Linda Casebeer

The Object of Desire

So many wild culinary promises in the pungence of curry, the curl of parsley. In basil, saffron, turmeric, allspice displayed in woven grass baskets, the open air market’s oldest form of seduction. And then the more subtle appeal of produce, lining row after row of stalls in their primary colors. Reflected in the dark purple polish of aubergine. In the way an orange reforms as a geometric solid with shadow when placed in the palm of a hand. In the inner secrets of flesh and seed that spill out when a seller, for the purpose of enticing a buyer, takes out a large knife and slashes open a tomato, a fig, or a melon. And beyond spice or produce, the raw essence of fish, so strong it overpowers. Hangs in the air. Seeps into pores, hair. Evokes the sense of earth’s broadest waters. The Amazon. The Mediterranean. Or a dozen others offering fish to market, each with its own array of sensual assaults. The background could be Iquitos, Istanbul, Barcelona; the foreground composed of hands and knives. At the fish stall, a buyer expresses Crab Orchard Review ◆ 21

Linda Casebeer

his desire. Before coins are accepted, before fish is wrapped in white paper and string, a sharp filet knife sheers away transparent scales flying up to catch the light. Beheads and guts the fish, her hands as intimate as a surgeon’s with the organs of lush purple, lavender, orange. Splits open the flesh to remove a delicate skeleton, so many small white bones resting only for a moment on the knife’s blade. Veined and worn, the hands are my grandmother’s hands with their knowledge of anatomy showing in every swift, sure movement she had used a thousand times before as she cleaned and fried the small fish we caught. At the produce stall a man buys one avocado, his choice determined by sense. In his hands, the knowledge of ripeness, a result of months of picking avocados. He describes cupping a hand under what is ripe. Without tugging or twisting, feeling the avocado give way, dropping gently into the palm with the weight of a woman’s breast. A Swiss army knife’s silver blade slips easily between the rough outer skin and the green gold flesh. With two swift vertical cuts toward the large central pit, the first slice is one long, elegant curve reflected in silver on the way to his tongue.

22 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Victoria Chang

KitchenAid Epicurean Stand Mixer

Another year has passed and she never thought she’d Get to thirty-three years without one. One day, when she was seven, On the kitchen table stood a chrome KitchenAid. Daring to put forth a vision, blended with Hearth, she promised herself that, On that special day of white cakes stacked to sky, Under a crescent moon with her man, Slung in his arms, gliding to band tunes, Emptying her heart to pour in his ambitions, Welcoming gifts from relatives she somewhat knew, In her arms, she would have a KitchenAid, Full of features and heavy-duty processing capability, Easy to assemble with a double whisk attachment, Head tilting back so it’s easy to Add ingredients and scrape down the sides of the bowl, Sensors maintain a constant speed regardless of load, And a soft-start feature reduces spattering. KitchenAids still line the shelves at Williams-Sonoma, In military formations on her thirty-third birthday, Their smooth bodies feel like butterfat, Curves covered with enamel, boasting form and function. Her eyes meet the hunter-green one in the middle, Everything she’s wanted in life in this box, Never imagined she would not be married by now, And still living with a roommate in a flat, Intimate with a new man every eight months, Dancing in circles, spinning around and around.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 23

Victoria Chang

Dragon Inn

Every night we waited for the last guests to leave—the stubborn leftovers who gazed, pointed at us, as if we weren’t there, weren’t sitting around the table. It’s feeding time, in a room with red lanterns layered with golden calligraphy. The cook turned the tray, judged the lobster, integer by integer, sucked the elegy out of its claw. A plate of capsized mussels, in a metropolis of thick, bubbled, eyed us as if we were alive. We rolled our eyes as the cook’s wife, hyphenated our air. She told us, your Chinese not so good. She scooped eggplant onto our plates. Marry money, a doctor, she said. I only remember the pacific booth, in the back corner near the kitchen, pulling me into the wall, 24 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Victoria Chang

into the gut of Taiwan, of my mother. There we snipped ends off Kentucky wonder beans, stuffed fortune cookies in wax paper bags, sealing Luck and Wisdom. I only knew the way from our house to the restaurant and back. I was diligent, obedient and shy— compatible with the dragon— now I am province, ten thousand acres from Dragon Inn.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 25

Huan-Hua Chye

In France fourteen and skinny

For two weeks we camped near the Breton salt farms, Huge squares of brown water rimmed with mealy white. The farmers in their straw hats walked the paths between the pools, Dredging dirty salt into piles with long wooden rakes. They sold that salt everywhere in Brittany, calling it fleur de sel. I ate it only once: we had broiled sardines, and Aurélie Showed me how to eat them, rubbing salt into the crackled skin, Eating the tiny bones whole with the moist gray flesh. The salt was coarse and soft; it stuck to your fingers, Leaving them redolent of the sea. C’est delicieux, I said meekly, Swallowing salt and crunching bones. I always spoke French, And they would exclaim over me: Mais elle parle tres bien! Before I left they had me Take my picture with a salt farmer. It was almost noon, the glare was blinding, And even on the paths salt crunched under my feet. The farmer was old, With salt crusting the folds of his knuckles. He looked behind us briefly At the expanse of barren fields, and the midday sun Froze his thick body motionless and colorless beside me. I squinted into the light, staring straight ahead. They said Smile, Stay still, and I did, always determined to obey.

26 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Huan-Hua Chye

Bog Town

Two years ago, think of it, I was in Vienna With the snow outside the windows, My life incomprehensibly charmed. We lay on our backs and touched hands Across the epic white of the double bed. Somehow I had thought this story, When I told it, would have some greater weight, But here we go, let me drop it The way he dropped the letter today Onto the pile of discards, acknowledging The sentence we inflicted on each other. Word by word and finally lightly, Our deliberate, casual goodbye. The snow outside lay on everything and the day Was Epiphany, and Mariahilferstrasse lay empty As the Austrians lay inside as we lay inside Touching hands on the double bed. The cake cost us thirty dollars, a Sachertorte Freshly rich from the Hotel Sacher. We opened the box, parted its nest of excelsior, Sliced out two pieces, began to eat Inconsequentially. How did two years pass by? The jam smeared our fingers, scenting us with apricot. The chocolate smeared our fingers, Lacing itself into our freedom. I did not feel free. I canâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t believe now That it has been two years since my fingers trailed Across my body, writing onto it in sugar My desire for decadence. His mouth went on filling with torte, The chocolate went on sliding through his body Veining him like a leaf, as love might, Crab Orchard Review â&#x2014;&#x2020; 27

Huan-Hua Chye

As we were tangled throughout each other As roots grow around dead earth, As bees crawl blindly through their homes. I think sometimes, Oh, darling, How did this happen to us? Looking at the room, Remembering the snow that lay outside And crushed us into our dreams. He would not mouth me clean, he would not lick my body In the small comfort that animals give as love. The color he would teach me later again, indelibly. Here is the bathroom where I washed myself clean. He said nothing as I walked back over to the bed And lay down beside him again. Eating cake, He said nothing and then closed the box and said to me, Are you done, let’s go to bed. And I went. It’s been two years and I cannot fathom How sorry he would have been, if ever, that I cried. Now, of course, it’s too late. He came over today and I stood awkward in the doorway As he looked over my shoulder at the room we had shared. The pieces of the life we had are slowly disappearing. I brought him the bag and he sorted them into piles, The pieces worth keeping, the pieces we’ll forget. Remember the snow and the taste of apricots. Has he forgotten that we made love and he licked me And that it was already too late for us, because two years later He will be sorting a pile of his old things on the table And then we will toss off goodbyes like crumpled letters. Tomorrow is a working day again. Forgive me, I’ve lapsed— Here is the story we’ve been missing. Frogger makes his way through Bog Town. There is nothing here but the possibility Of catching a ride to another town, And to get to the next place requires honey. And there are two ways out of this place. First, Speak kindly, bargain, work things out. The bees will give you honey if you ask for it nicely. They will offer it over and over again. Second, the shortest path. Scream your way out. Hurt the bees enough and they will give up. 28 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Huan-Hua Chye

There is the honey and the story ends here, The same always: bring your honey to the bear, And ride on out on his cable car. Inconsequential. There are always these transitions Where it seems like the world will end, But they are, after everything goes on, transitions. Years pass inconsequentially and you realize That the way they passed was inconsequential too. How much would my present have changed Without him there? How much will it matter That I was free in Vienna, but bound in this time? Frogger makes his way to the riverboat If the bees live or if they die. There was a future for me That lay waiting here regardless of whether, In the end, we had fought or we had tried. As it is, we became separate. And if I toss off another story Of fighting for the sweetness that might have saved us, The last day in San Francisco that his breath warmed me, The night I walked away into someone else’s kiss, It will make no difference at all, for here I am at the crossing, The riverboat before me, the sun beating down, No way back and no way forward but this. And would I have been better off, or worse, If none of this had happened? We passed Three years together, and have I changed at all? It’s been two winters since Vienna. That cake is long gone. Somewhere in Bog Town, some bear or some man Looks up, thinking of me, and licks his lips, Caught in his slow memories of sweetness.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 29

Geraldine Connolly

Morel Hunting

Past the tent city of pickers, past the drainage ditch, fallen cedars, you search for elusive morels at the far edge of the North Fork. How sure you are you must have them—devils’ thumbs, like foreign cities, or new love, fleshy and sexual—accidents of fire and water risen from the charred timbers like Lazarus. Along the rushing spring run-off, ashen skeletons of lodge pole litter the muddy loam. Only a vision with brandy and butter, veined domes drowned in shallots atop grilled tenderloin, keeps you hunting them, driven, clutching your empty basket, wanting a fleet taste of the sublime unmanageable— riotous as a preacher, bent over a forest stripped by fire.

30 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Geraldine Connolly

Lost Summer House

My father sang at the cast-iron stove, Already dressed in fishing clothes as he spread Buckwheat batter along the griddle, then delivered A hot tower of silver dollars to each child’s plate. We poured syrup from a log cabin container, Another slow summer morning of pine and lake Begun—minnow netting and blueberry picking Planned for the far inlet past a rickety bridge— Across a ravine, like the bridge we crossed to morning Through boggy dream thickets, vines and dark rushes. No choppy waves yet dissembled the horizon. No future raised Its disappointments, bitter divorces, heart surgeries, Every promise comfort, the pleasure of a day’s currency. Beyond the corner cupboard with its stenciled plates, Eight window panes glitter, a mirror of fresh pines ascends, And past it, the lake ripples into blue washboard, Wave-tips agleam, silver as new-minted coins.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 31

Geraldine Connolly

Blue Ware

Porcelain. Some mothers took down their patterned plates for meals: china gravy boats with turned handles, gilded egg coddlers and lidded soup tureens. Some mothers used their dinnerware, but mine stood china behind glass in a locked oak cupboard. Platters and tall-footed tea cups lined up, beauty deferred, saved until work was completed, for Communion lunch, feast day or wedding anniversary. While our family chopped and weeded, scrubbed and hung work clothes in the yard, hens clucked, fluttered in their chicken houses. At mealtime, ironstone prevailed, repository of parsnips and stew meat, pale homely sides of covered casseroles stained by the crusts of many meatloaves. Plates nicked by the knife and fork were left to soak in a greasy sink. In the corner cupboard, her dreams rested, purchased with egg money, kept in their accustomed places, with scenes of an indigo countryside, bridges and parks, columned estates

32 â&#x2014;&#x2020; Crab Orchard Review

Geraldine Connolly

where lords and ladies picnicked shamelessly across the painted plates, the ladies ripe in lawn dresses on their way to the pleasure boats.

Crab Orchard Review â&#x2014;&#x2020; 33

Deborah Cummins

The Season’s First Apples

At the farm stand, among the crates of late tomatoes and corn, the season’s first apples blush at their debut— smooth, unmottled beauties too pretty to eat. For days, the ones I choose adorn my kitchen shelf, their stout stems like perky caps, tams, perhaps, the kind without protective earflaps. At the open window, the wind is disguised in the stillness of trees, the luffing sails in the harbor. Nowhere in my radio’s broadcast is there a forecast of snow. I have no need for socks or a sweater. But at the sound of my first bite of the season’s first apples, boots crunch through icy layers. Frozen tree limbs stutter against the roof and gutters. And the stove gapes open, ready to make of another cord of wood ash. How solitary the flame of a single struck match that on certain cold nights seems like the only salvation.

34 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Chad Davidson

Truffle

Excavated, this shriveled fruit quieted the hounds with a cross between garlic and the very root they tore it from, more expensive than gold or saffron, the meat of its heart. Outside Perugia, we stumbled into a square cluttered with menageries of grappa bottles, wild boar, stacked baskets of black truffles. You were so beautiful sifting over those stones like a miner. Later we walked in the rising rain, the near-nil heft of the brown paper bag and the truffle inside I cradled. What were you counting in the distance? The returning crows, the smokestack grid, the miles of cars and wives and husbands who could not, any of them, sense this disinterred minute in the plain brown bag I open now in front of you. Two plates of steaming pasta, a bottle of oil

Crab Orchard Review â&#x2014;&#x2020; 35

Chad Davidson

cold-pressed, and this black truffle. What were you counting that kept you silent in the rising rain? It is late. The slicer’s set fine. You talk about a morning in Alaska with snow so hard the world lost orientation, and how everyone watched the last snow of their lives. You are telling me not to wait any longer. I set truffle to slicer, knowing the scent from this bit of the earth we’ve walked for almost one year now will not fade for days after we’ve left this place.

36 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Chad Davidson

Strozzapreti —Italian pasta, literally “Priest Stranglers” Bellying up to your door, the overbaptized arms, stoles worn thin about the neck: who but blasphemers wouldn’t open up? They enter, light-headed from confession, call for linens, like a tether to save themselves from floating past the masses. All the saintly portions, the sauces bland, angelic—a lording over moderation. There in heaven, come to table, perfected hands hover, poised to carve the thin, light meat, something kept back like the gnawing voice they obey. They could do worse. You, too. So go on, keep strangling. Each knot of pasta brings them closer to the mouth, the hell they go through starving at the plate of God.

Crab Orchard Review ◆ 37

Chad Davidson

Bread

The egg-glazed challa that dazes my flattered guests, my fake passover flung into the fire of illinterpreted tradition, or the Hostess Twinkie with its century’s shelf-life, brioches I palm into an eyeballsize then pound thin as wafers: the first great resurrection, alive with myth and yeast, no wonder bread predates the words we conjure. Loaf, related to lord and lady. Pan, as if bread were universal like sweat and prayer: what we do to check impious rising. Because Chinese combines bread and bone in one character, two bread mean wealth or virility. And three extravagance or cancer. I’m lying. But consider the metaphor: we eat our own strange bedfellows. Because in my Anthology of Self-Centered Etymologies, bread derives from bird. Flown free of its signifier, this challa

38 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Chad Davidson

hovers over history, preying on my passing love of underlings who overlive.

Crab Orchard Review â&#x2014;&#x2020; 39

Chad Davidson

Ossi di Morto —Italian cookie, literally “Bones of the Dead” Savor these unnamed, our tongues still heavy with vin santo, a miracle or vice—the depths we crave this slow digestion of the past to something less substantial. Mostly in Rome, it is 1978 again as the axe falls on Mary. Witnessing the attack on the Pietà, we too would swab the marble like mad to catch a sliver quick under the skin, sick, believing the flaw, our bloodied palms gobbling up some resurrection, our mouths in search of veins of sugar we’d swear we tasted. Being tempted once, we always catch the spark, like children crushing peppermint in the dark. On the other hand to eye those piles under glass in cafés, the sinless fingers clawing in vain, some hardened part of us still wants denial,

40 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Chad Davidson

burial, their names spoken, given back. But ah! how anonymous that grate of teeth on bone, that aching, false flare of indulgence igniting all our mothers swore would be the death of us.

Crab Orchard Review â&#x2014;&#x2020; 41

Nan Leslie

Chez Noir

In front of a backstreet building, a factory rescued from the wrecking ball, down by the wharf where fishermen still docked, their calling cards carved from ancient mariner driftwood, a rusted cowbell hung from a lamppost. Ringing it loud was the only way to gain entry. No doorknob was on the outside, no windows, and you should be sure to have a reservation if you bothered the boy who manned the door. Their hours were inconvenient: 6 P.M. to 9 P.M., with one seating per evening. The wait for a reservation was six months. Chez Noir was its name—not that anyone could read it—there was no sign out front, no menus, and no listing in the Yellow Pages. I first came to Chez Noir as a surprise for my fiftieth birthday, feeling sorrier than happy at reaching this half-century mark, wishing to reclaim limber limbs and optimism from past decades. All this awareness weighed me down, convinced me to take things slow. I watched my elders with newfound fascination, followed their cues while whittling my world down to a manageable size that included a handful of old friends and my only child. My daughter Casey accompanied me, a darling of a woman who had materialized as a Generation X licensee, the proud owner of a pierced nose and silver-tipped lashes that flickered impatiently at her dysfunctional mother. I had always believed in the antithesis of evolution, the growth spurts of the mind compensating for my decelerated metabolism. It wasn’t until Casey had the burden of thirty years behind her that she executed an abrupt turnaround. Now everything I had ever said or done was embraced as gospel to the grave. I wasn’t bitter, only I had stopped lunging for the goal line, content to make my way inside easy boundaries with minimal distractions. Casey was one of them, forgiving me fourteen years too late for losing her father who had never in his life done anything less than extraordinary. He lived off his looks—taking everything and giving only what he had to—and if you asked for anything more he folded like an accordion and begged to be retired. 42 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Nan Leslie

Here she was banging on my door. “Come on, Mother. I know you’re in there.” Where else would I be? I had given up driving, sold my car. In fact I rarely went outside except to smoke. Politically correct, if I was unlucky enough to be in a populated area, I stood well off from the flow of people pounding by. Even so there were always a couple of drama queens who made little coughing noises as if the sky lacked enough air for them to breathe. I took a quick peek at myself in the mirror. I’d actually found my makeup this morning. Not quite the professional job I was capable of, but within the subtleties of highlighting and shading gleaned from my early days with Mary Kay, I still reflected a marginal silhouette of my younger self. Casey had been proposed marriage a half-dozen times, wore size eight dresses from Banana Republic and Gap, and refused to date men who weren’t fully vested in their company’s 401K for at least ten years. She was the only woman I knew who went hiking through the woods in platform sandals, carting a hemp shoulder bag with a readymade gourmet picnic in a box. She worked as a marketing consultant for the advertising giant Baskins and Bromwell, and was one of the chosen few in San Francisco who could afford her own apartment. Her boss was her landlord, charging her a ridiculously low rental fee that barely covered the water bill. With henna curls and collagen lips, she darted around in a champagne BMW, cell phone plugged to her ear, always in-between meetings, on her way to somewhere important. I watched her with awe, this woman so bright and brave and having everything her own way. I had fallen into complacency, left everything to chance as if my part in life was to merely show up. From the time she could walk I had preached to her about men—as if her foresight could make up for my hindsight. She had grown up knowing exactly what she had to offer and how to use it. But in using her as my second chance, I had lost sight of what she needed from me. “I’m not you, Mother,” she had often shrieked in that grating sophomoric voice that teenage girls master. And I had wanted to yell: you think you know life; just wait until it has you in its clutches. She called me paranoid, overprotective. I said what all mothers say, “Wait until you are older.” Everything that came after: the live-in boyfriends, the power job, the driving force she’d become—she poured success in my lap as if we were keeping score. If only I had preserved what I had been so anxious to defeat. I needed Crab Orchard Review ◆ 43

Nan Leslie

to get to that place again, and it was that thought above all others that woke me early, my clothes soaked through, just missing her. My daughter had become an even more jaded me. Two minutes after she walked through my door she was already rushing me. “Come on, we’ll be late.” “What should I wear?” “It doesn’t matter where we’re going.” She eyeballed her Rolex. “Right,” I said, turning to my clothes closet full of orange sale tags still dangling from sleeves. I always found fabulous treasures: red leather pants, a pair of stiletto pumps, a blouse with a missing midriff, knowing full well they were useless. But I couldn’t stop myself. Just seeing them hanging there gave me a kind of hope, a muted, tender joy. The Japanese silk pantsuit in a size eight that still carried the $400 price tag marked down to $69.95 would be waiting for me when I returned. “I’ll help you,” Casey offered, as I rummaged through racks searching for the three pairs of pants and two sweaters that actually fit me. “I’ve got it,” I said, selecting the old standby—a pair of black polyester pants and a lavender sweater set chosen for its remarkable stretching properties. I finished the outfit off with a choker of graduated pearls and slipped into my favorite pair of dressy flats. “Ready?” I asked, eyeing her chunky leather boots and Mod Squad dress that looked like it would barely cover my foot bunions. “Better not get a run in your stocking,” I said. “They might arrest you for indecent exposure.” She bussed my cheeks in a decidedly British way. “Happy birthday.” “You’ve been seeing that Alfred Fleming from Masterpiece Theatre again, haven’t you?” I accused her, as she turned off the television and I locked the door behind us. She had a thing for Brits. “Oh, Mother. I told you. I’m dating Saul now.” “That’s right,” I said in the car, “the doctor. When are you going to bring him around? I’m ready to clasp him to my bosom.” “You’d clasp a paranoid schizophrenic to your bosom as long as the letters M.D. followed his name.” We parked in a lot near a line of trendy eateries. I thought we would be having the traditional birthday dinner by the wharf celebration, filled with good wine and lobster pie and my favorite 44 ◆ Crab Orchard Review

Nan Leslie

dessert—white chocolate mousse. But she continued walking until there wasn’t a single restaurant in sight. “Where are you taking me?” “You’ll see,” she said, picking up her pace as I huffed along behind her. How she could navigate in platform soles thick enough to be certified as Red Cross flotation devices, I’d never understand. Finally she stopped, taking hold of a rope and ringing the bell like the place was on fire. I backed up, suspicious, eyeing both sides of the street for an advancing army of revelers, but she shook her head and gave me a stern look that told me to behave myself. A young man finally answered the door. (If you want to call it a door. To me it looked more like the side of a barn with a hinge.) “This way, please.” He turned and started walking, leaving me to close the massive latch that held the door from the inside. “Come on,” Casey whispered. Why were we whispering? It was dark inside. I could barely make out my own feet and found myself clutching the back of her dress. “Wait,” I hissed. “Give me your hand.” I let her lead me, with the boy in front leading her. We walked through some sort of corridor and then paused for dramatic effect. “Ready?” she asked. “This is it.” I’m not sure what I expected. I suppose a surprise party in full swing, a raucous throng of Casey’s friends in high spirits after their third margaritas, lime-tinted tongues crying out “Happy birthday!” The boy opened a door and the darkness was so deep I could reach for my nose and miss it. I heard classical music playing softly in the distance—Chopin’s etudes, it sounded like—and I figured there had to be more coming, so I played along, praying I wouldn’t fall over someone’s feet on the way in. “Are we there yet?” I asked, and was met with a hostile “shhhh!” I put my hands on Casey’s shoulders, and I suspected she had hers on the boy’s—the three of us like line dancers at a wedding—at any rate someone was leading us in the direction of murmuring, the gentle ping of crystal raised in a toast, and I thought: now they will turn on the lights and illuminate my birthday guests. We stopped. “Here you are, madam,” the boy said, and I heard a chair grazing the floor. He took my arm, guiding me. I felt for its back and gingerly lowered myself, brushing my knees against a tablecloth. Casey sat opposite me. Pieces of conversation floated up and down the length Crab Orchard Review ◆ 45

Nan Leslie