9 minute read

S\u00E3o Paulo

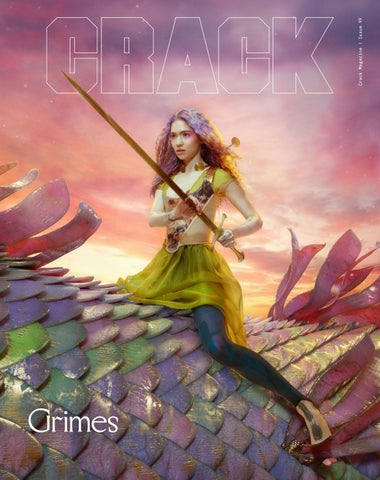

from Crack Issue 99

São Paulo’s nightlife collectives are building a home for themselves.

In the city's club spaces, communities kick back at their political landscape.

I must have been barely 15 when I first walked into a gay club in my hometown, São Paulo. I remember it distinctly – my hair short, half-dyed blue, eyeliner beyond my years, a leather collar I bought at a pet shop, holding a vague notion of my queerness and fake ID in hand. The building used to be a church in the 1950s, turned theatre, abandoned, and then into a nightclub. It was called Glória, meaning glory, or praise. Above the door, painted purple, the old church adage was still there: “A space of prayer for all peoples”. A deep breath and I took a step into the unknown.

Glória might be shut down now – likely demolished, I haven’t been there in years – but other buildings rise, spaces are created, and for parts of the LGBTQ+ community, nightclubs remain the closest space they have to a place of worship. Worship not in the God-fearing way that often insidiously controls many aspects of Brazilian society, but in the way of shelter. Nightclubs are where we go to feel safe, to sweat and enjoy being alive, to flirt in times of despair. Places to start a revolution.

Unfortunately, much like many of their counterparts worldwide, the LGBTQ+ spaces of São Paulo aren't without their own issues. They are, in many ways, reflections of Brazil as a whole: a country where unparalleled creativity and diversity are forced to exist alongside structural and violent sexism, homophobia, transphobia, racism and classism.

Despite hosting one of the largest pride parades in the world, Brazil holds the highest rate of violence against LGBTQ+ people, with one of us announced dead every 19 hours. The perpetrators vary (from police to middle-class teenagers) and so do the victims, but trans women and those from marginalised communities who come from low-income backgrounds remain those most affected by daily aggressions and institutionalised prejudice.

This violence has become even more obvious as of 2018, following the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president, a man famous for saying he’d rather have “a dead son than a gay son”, his government flanked by conservative Christians and the military.

During his election period, a trans woman was murdered in the centre of São Paulo, the perpetrators allegedly screaming the name of the current president. There have been ties established between his family and those responsible for the death of activist Marielle Franco, and homophobic threats have driven Brazil’s second openly gay member of Congress, Jean Wyllys, to flee the country in fear of his life.

But even amidst all this violence, LGBTQ+ Brazilians are not unfamiliar to resistance. As such, over the past few years, several performers in the São Paulo scene have been working hard to eradicate institutional intolerance, both within club spaces and outside. They are DJs, drag queens, singers, dancers and multidisciplinary artists, fighting fearlessly for the right to expression. They are angry, chests naked and covered in glitter, claws out, refusing to stand down in a political landscape that promises to become more oppressive every day.

Standing at the epicentre of this revolution in the São Paulo scene is Mamba Negra, a party founded by DJ Cashu (Carol Schutzer) and Teto Preto’s Laura Diaz back in May of 2013, after both women became fed up with the financial and social inaccessibility of mainstream clubs.

“The expansion of almost all cities in Brazil is characterised by a lack of urban planning and public policies that take people into account,” explains Cashu on the decision to host Mamba Negra in dilapidated spaces throughout the city. “Because of that, there were many buildings left completely empty, either neglected by the government or abandoned because the owners were in debt. Open wounds in areas left forgotten, which needed to be exposed and discussed. When we hosted parties in these spaces, we exposed them [for the first time] to many people who were attending – as a way to question them, but also party in grief.”

Mamba, as it’s affectionately referred to by those who take part in it, is not only the initial meeting place for many in this new wave of Brazilian creators but also the one common thread that has been tying the scene together for the past few years. It's a live organism, thrumming, expanding.

“The scene in São Paulo is a universe of its own. A playful space with incredible, talented people, and a huge amount of diversity. Because we are Brazilian and Latin American there is a lot of care and a sense of family,” explains Amanda Mussi, a Brazilian- Paraguayan DJ who runs the monthly techno party Dûsk, a present-day staple for the queer community of São Paulo. “The artistic expression here is unique. I feel like our lack of privilege as a colonised country makes our decision to express ourselves artistically one that is made with a lot of effort and courage. We have had, and still have, very little financial access to have infrastructure, but we always make it happen.”

“Outside [of Brazil],” Amanda explains, “[performers] often have access to everything from the beginning, from equipment to studio spaces.

First world countries have a socioeconomic landscape that offers a huge amount of privilege to create a scene that is professional and organised government-wise. I believe that both not having privilege and being overlyprivileged affects your reality. It affects whether or not you are aware of your surroundings. The harder or easier you have it [as a creative], the more genuine or bland the results of your art are.”

An icon of the scene’s signature defiance is Teto Preto. Part of Mamba Negra’s ingenious family tree, they are a music and performance art group intrinsically woven with politics that pointedly defies any kind of definition, fronted by Laura Diaz, who goes by the name CARNEOSSO (a portmanteau of flesh and bone). When she writes, it’s poetry. On stage, her body language, combined with that of performer Loïc Koutana, is close to the construction of her words: an artistry that is instinctual, animalistic, but simultaneously deeply considered and emotionally savvy.

“Women – black women, lesbian and bi women, trans women – rarely have a singular moment in which they choose: I will be an artist,” she explains when asked what led her to the stage. “Everyday women tell themselves and the world what they want to be. [My experiences] are part of what makes me an artist, it is in these moments that I reaffirmed my need to conquer the right to become who I want to be.”

Artistically, Teto Preto tackles many issues pertinent to young Brazilians. Like abortion, still illegal in the country. Domestic violence. The statesanctioned brutality inflicted upon those in marginalised communities – especially trans women, lesbian women, black women, poor women. Teto also refuses to make the questions tackled by the work of the new wave of Brazilian artists soft and easily digestible for American and European audiences – something often encouraged by largescale event promoters.

A key participant of the scene also at the helm of these issues is Misael Franco (also known as Euvira), a multidisciplinary performer, party organiser and drag queen originally from the outskirts of Salvador, Bahia, but now living in São Paulo. He's the founder and one of the driving forces behind Coletividade NÁMÍBIÀ, an electronic music and visual art collective. Coletividade is currently comprised of over 40 black, majority LGBTQ+ artists. Their focus is on fighting racism, homophobia and classism within the techno scene through reclaiming space, empowering young creatives and contesting the whitewashing of a genre rooted in black culture.

Getting his start in the São Paulo electronic scene as a van driver back in 2016, bringing party-goers to the centre of the city while fully glammed up, Misael quickly began questioning the absence of black people in these spaces of celebration. “I asked promoters why there weren’t any black people in the spotlight. Where were the artists, the DJs? They would say ‘I don’t know any.’ So I gathered the artists I knew and researched those I didn’t know who could be a part of these parties. That’s how Coletividade NÁMÍBIÀ was born.” Today, Misael has played a role in discussing the whitewashing of not only national parties, but also international festivals such as Dekmantel, who came under fire this year for the absence of Latin American artists in their Amsterdambased line-up, despite hosting a series of festivals across South America in the past two years.

One of the members of Coletividade NÁMÍBIÀ is Ana Giselle, who runs the party and art project MARSHA!, focused around uplifting the oftensilenced voices of trans people in the São Paulo party scene. After getting her start as a DJ in Bahia’s club circuit back in 2014, Ana also established TRANSFREE, a structural inclusion policy now adopted by locations country-wide, which offers trans people free access to events, gigs and festivals.

“Around 2015 I coined the term ‘TRANSÄLIEN’. It was born out of the displacement of my existence, as an individual who is trans, monster-like and ‘strange’ – shunned categories in which I fit in, am proud of and seek to resignify,” explains Ana. “I shift the social concepts imposed over my body and translate them into art. It was the way I found to live my subjectiveness, and that is where I come from when I establish spaces where people who are ‘different’, like me, can have a place.”

Ultimately, standing behind all these artists at the forefront of the São Paulo scene is one collective idea: that LGBTQ+ parties should be spaces not only of celebration, but also political awareness and support. That safety in these spaces means safety for everyone, not just white, cis, middleclass gay men. And they’re willing to fight for that safety with all it takes.

“Politics are made everywhere,” explains Ana Giselle, referring to the inclusion of politics in party spaces. “To me, it is the ethical duty of dissident bodies to use their voices, be they artistic or not. Starting debates through cultural production is a political strategy. As I am a political body, I take my discussions and perspectives wherever I am.”

Coletividade NÁMÍBIÀ’s Misael also echoes Ana Giselle’s sentiment and adds that, as a black gay man from the north east of the country, the Bolsonaro government only means more of the same oppression. The resistance will continue as usual, the spaces created continuing to blossom in the face of adversity.

“I believe that there are many ways to protest – there are people who write, there are people who perform, there are people who are so saddened by the state of things that they get sick,” he continues, “and there are people who throw parties and create spaces that are not only entertaining, but social.”

“Black people will be in those spaces, speak about things they experience collectively and become stronger. Trans people, queer people, people from the outskirts will find themselves and do the same. Because there are more people like them,” he explains. “We like partying. That’s why it’s important to see parties as ways to discuss politics. Yes, we meet to celebrate, to have fun. But it is also a space of sharing. A space of resistance. A space of exchanging love. A space to heal yourself. To be alive.”