10 minute read

Practice, planning paid o as Lansing hospitals met tragedy

It helped save lives after MSU shooting

DUSTIN WALSH

Advertisement

Dr. Denny Martin was at a business meeting last Monday night near the state Capitol in Lansing when the alert came through: A mass casualty event in progress on Michigan State University’s campus just 4 miles away.

Martin, the acting president and chief medical o cer of E.W. Sparrow Hospital, the region’s only Level 1 Trauma Center, immediately rushed back to the hospital.

Unsure of the number of shooting victims, the hospital initiated its triage protocol to call in appropriate sta .

Within 30 minutes of the initial alert about the shootings, the rst of ve victims was rushed through the emergency department doors. Within minutes the other four victims arrived. Waiting for them in operating rooms were three trauma surgeons and four anesthesiologists, up from one each the hospital usually sta s overnight.

Martin changed out of his suit and into scrubs and, as is protocol for the top administrator during an allhands event, operated as the oor leader — an “air tra c controller” as he called it — as victims rolled in.

“Lots of people came into the hospital to help and we needed some oor leadership,” Martin said. “My job was also to help get key resources. We had to alert the local blood bank, the local Red Cross, the lab, radiology. We ran ve (operating rooms) most of the night, so we needed adequate supplies and sta there to prepare and sterilize equipment.” roughout the night, neurosurgical, cardiothoracic and general surgical teams worked to save the students. One of the wounded did not require surgery, Martin said.

So many sta ers turned up at the hospital that night to help, administrators eventually had to turn them away.

Martin could not comment on the speci cs of the injuries, but said there were brain and spine injuries and all were “very life-threatening.”

Across town, sta at McLaren Greater Lansing Hospital were also preparing to take any additional victims.

“We didn’t know how many casualties there was going to be, there were so many di erent reports,” said Dr. Tressa Gardner, executive medical director for American Physician Partners, the group that operates McLaren’s emergency departments. “We didn’t know how long it would go on for because at that time, the perpetrator hadn’t been captured.” e hospital, led by Gardner, sta ed up to three surgeons and ve available operating rooms immediately and prepared a second wave of sta to go in at 2 a.m. to assist if needed. is was Gardner’s second mass shooting event in the last 15 months. She led the response for McLaren Pontiac Hospital, which received the most severely wounded students from the Nov. 30, 2021, mass shooting at Oxford High School that killed four students and injured seven other people.

“We were prepared because, unfortunately, we are learning from each (mass shooting) we go through,” Gardner said. “Communication up to and during the event is the most important factor.”

Gardner said the Pontiac hospital was overwhelmed during the Oxford shooting, and there were hiccups in communication, none of which impacted care, due to cell tower overuse during the shooting. Parents, students and rst responders were all competing for nite radio waves.

On the night of the shooting, Sparrow was at capacity caring for the shooting victims, so emergency medical services routed all other emergencies to McLaren.

By early Tuesday morning, the four victims were out of surgery at Sparrow and alive, something Martin credits to the speed in which rst responders got the injured students to Sparrow and the e ective communication of the sta at the hospital.

“It’s all about time,” Martin said. “From the initial assault to getting medical attention in our ED, it happened quickly. Our preparation worked and we had adequate sta ng to handle the situation. You can have the best individuals, but without communication it all falls apart. It’s why those ve individuals were still alive this morning (Tuesday).”

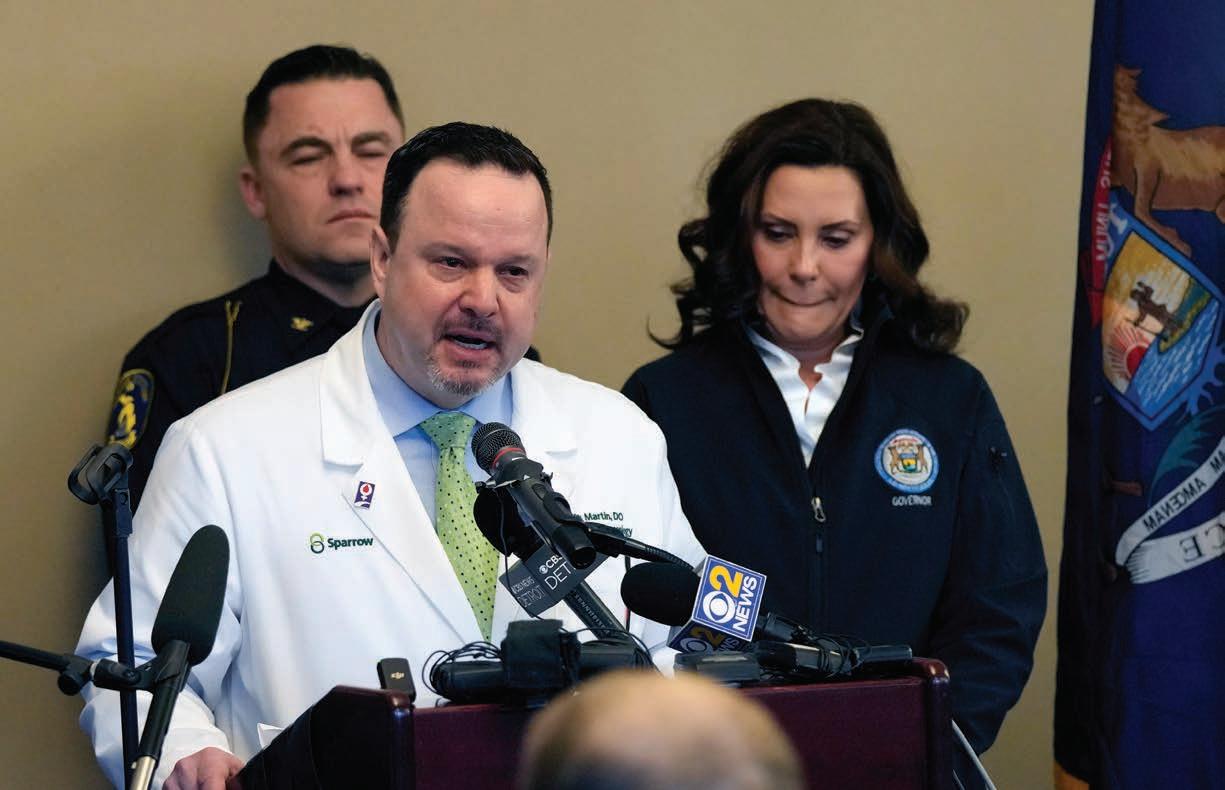

At 8 a.m. Tuesday, Martin broke down in tears at a news conference to update the public on the condition of the victims.

“ is is something we practice for, but never want to do,” a choked-up Martin said at the brie ng with tears welling in his eyes. “We did it reasonably well, and I’m proud of everyone.”

(obstetrician) by training, so staying up all night delivering babies is what I’m used to. But not the stress on our team. By morning I was emotionally drained. I’ve been through the full range of emotions — profound sadness, anger and now pride about how we responded.”

Martin said every hospital in America needs to, if it hasn’t already, develop an e ective mass casualty response plan.

“Our plan got us through the night with positive outcomes,” Martin said. “You have to have a plan because it’s an unfortunate reality that most hospitals will have to deal with this at some point.”

Sta at Sparrow will eventually undergo a debrie ng of the day’s events, a spot check on how they did and whether everyone is OK.

“ e debrie ng helps with the shock component,” Gardner said. “It’s not about us, it’s about the victims, but we’ve all been impacted. e victims, and their families, those lives are changed forever. e rst responders, those lives are changed forever, too.”

McLaren was prepared, Gardner said, and will be prepared for the next mass shooting. But she wants change.

“OUR PLAN GOT US THROUGH THE NIGHT WITH POSITIVE OUTCOMES.”

By mid-morning, his sta sent him home to get sleep. He had e ectively been at the hospital for more than 24 hours.

“It was a long evening,” Martin told Crain’s on Tuesday night. “I am an

“Can we handle mass casualty event? Yes, but I’d rather we stop them before they happen,” Gardner said. “Whether that’s gun control and increased mental health awareness, we need to nd a solution. I don’t want to do another one of these, but my fear is that I will.”

Contact: ose systems are among the more progressive options safety experts recommend, but they aren’t bulletproof. ose enhancements require a thoughtful approach and dedicated resources to implement them, Gundry said.

Individual GVSU classrooms can also be locked from the inside to prevent entry, regardless of whether a campus lockdown is happening, through a locking system GVSU installed a couple of years earlier.

It’s impractical to close o large sprawling college campuses, said Craig Gundry, a security consultant with Tampa, Fla.-based Critical Intervention Services Inc.

But there are physical security measures schools should employ to mitigate potential risk, especially on campuses with older historic buildings.

“Very rarely do I walk into a school where they have the budget to deal with all of these concerns," he said.

Keeping campuses safe

Active shooter incidents in the U.S. are on the rise. e number of shootings doubled to 61 in 2021, up from 40 the year before and 30 in 2018 and 2019, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Active Shooter Incidents report. ese shootings are happening in more states and killing more people, according to the report.

Given that, universities try to ingrain in faculty, sta and students a culture of safety, said Mark Gordon, chief of police for Oakland University.

Safety is a community partnership, he said. Everybody has to do their part, even if looks like it’s nothing but it rises to the level of suspicious in their mind.

“We’d rather they call 10 times and it’s nothing than the one time they don’t call and it turns out to be a tragedy on our campus,” Gordon said.

OU and Michigan’s other public universities o er active-shooter training programs for students, sta and faculty, online and in person. And they engage in scenario planning to establish how they will collaborate with other law enforcement agencies in the event of an emergency.

“Many of the things you saw at MSU, with other agencies coming to participate, those are things that have to be thought out and planned,” said Walter Kraft, vice president for communications at Eastern Michigan University.

You’ll never replicate exactly what partments on duty 24-7, campuswide cameras to monitor activity, key card access to residence halls and emergency noti cation systems to push text alerts to students, faculty and sta in the event of an emergency. e 1,000 cameras on EMU’s Ypsilanti campus enable the school to identify and record issues sometimes as they are happening so police can go back and track activity, Kraft said. e University of Michigan and Wayne State University declined to talk with Crain’s about the safety measures they’ve put in place on their campuses. you will confront in an active shooter situation, he said. But practicing your response ensures you have the systems of communication in place and processes in place to enable everyone to do their jobs.

Oakland University, whose 1,400acre campus crosses into Rochester Hills and Auburn Hills, installed panic and intrusion alarm systems and over 200 “blue light” phones mounted on 10-foot towers to instantly connect to campus police in emergencies.

EMU, GVSU and OU are also among the public universities that installed swipe cards on residence hall doors.

“As we continue to upgrade campus, we are putting more of those (key card) systems in place…It’s an ongoing e ort to add the card readers to all of the buildings on the campus,” OU's Gordon said.

But in a statement, WSU said that, like Michigan State and all universities, it constantly assesses its preparedness for crises of all kinds, especially mass shootings like the one that occurred at MSU on Monday.

“Our observation of MSU... is that they were really on top of it in the way they communicated about it and the way they handled a very, very tragic and terrible situation,” Kraft said.

Preventing and responding to issues

ere are some constants in security measures at Michigan’s public universities. ey include police de-

“Our professional police department, like MSU’s, is highly trained for such situations and is fully connected with other law enforcement agencies to ensure an effective and coordinated response," the university said in the statement. " e safety of our community is paramount, and preparedness is a constant, ongoing process. Our crisis team with representation from around campus meets regularly to discuss crisis scenarios and our responses.”

Missed opportunities

Still, some universities are missing opportunities to improve safety on campuses, said Gundry, whose job at CIS is to help manage the risks of mass homicide for schools, colleges and universities, governments here in the U.S. and overseas and other clients. lockdown systems can also present a problem for people seeking refuge in an emergency, Gundry said. at’s something GVSU, which has a full-time emergency manager focused on mitigating threats, implemented in 2019. With the touch of one or more buttons, it can e ectively lock down buildings on its campuses, Knape said.

First and foremost, he recommends audible mass noti cation systems.

“In the event someone isn’t looking at their phone, or it’s on silent, (universities) need public address systems,” Gundry said. Although students, faculty and sta get alerts on their phones, there are no public address systems because of the size of the campus.

With historic architecture on campuses and new construction not designed for active-shooter scenarios, windows and door locks are other key areas to address, Gundry said. Tempered glass on doors and windows can easily be smashed in, especially if broken by a bullet. He recommends upgrading existing glass windows with security grade, anti-shatter lm. (Intrusion-resistant glass, which has a polycarbonate inner layer sandwiched between glass is among the least penetrable, but more expensive.)

Another common issue Gundry said he sees on campuses is the choice of locks for doors. Speci cally, classrooms, lecture halls and ofces need to have locks on the inside of doors.

In some old school buildings, classroom doors can only be locked with a key from the hallway. ose locks and the inability to lock a classroom door from the inside led to the deaths of 26 people and injury of two dozen others during shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and Virginia Tech, he said. Dorms, which have di erent code requirements than school buildings, typically have internal locks on doors that students can secure from inside their rooms, he said.

Some institutions have opted to use maglocks on exterior and interior doors, and those can pose issues. Maglocks use a strong magnet on the door frame to hold the door closed. However, to adhere to re codes, those locks must disengage if a re alarm is pulled.

Gundry said that’s happened in some places to draw attention to an issue or to force people out.

“ e best approach is to make sure we have the right kind of electri ed locks that feature a lock-out function,” he said.

Such systems enable people inside the classroom, lecture hall or o ce to turn a thumb turn from the inside of the door to lock it. It disables the electri ed function, and the key card won’t work anymore, he said. But the door can be opened to admit someone seeking refuge and will lock again when it’s closed.

In 2017, GVSU installed locks on classroom doors that can be individually locked by occupants to prevent entry, regardless of whether a campuswide lockdown is implemented, Knape said.

Egress or the ability to escape from buildings is another thing Gundry said schools should consider. He’s also a big advocate of gunshot detection systems that hear the gunshot and see the muzzle ash or the heat from it and then sound an alarm.

All those measures come at a cost, Gundry said. But another measure he recommends is not as capital-intensive.

“College campuses use those maglocks a lot...it’s a major vulnerability” and a high priority to replace them with di erent hardware, he said.

Key card access to residence halls, academic buildings and gathering spaces can improve security by preventing those who don’t belong from getting into buildings. But if a shooter is a student and student badges provide access to university spaces, “we have a problem,” Gundry said.

Lockdown systems can prevent access in those cases.

While a useful prevention tool,

A lot of universities are reluctant to create disruptive drill activities on campuses, Gundry said. However, he said universities ideally should have a short presentation every semester that teaches students how to address emergency situations, such as active shooters, and how to spot and report potential behaviors of concern.

“Simply putting it on the website doesn’t mean you’re educating your students.”

Concerns vary from school to school, Gundry said. Some schools may have great windows, but they’ve got bad locks. Sometimes, it’s both.

“Quite often it does require ...(a) budget forecast over multiple years to really bring themselves up to a high level of readiness,” he said.

Contact: swelch@crain.com; (313) 446-1694; @SherriWelch