11 minute read

to keep teachers

TEACHERS

From Page 27

Advertisement

So far, though, the opposite has occurred. While more teachers retired in recent months than usual, perhaps to avoid a return to in-person instruction, fewer teachers changed schools during the last school year than in previous years, a Chalkbeat analysis found. e decline in turnover should not be surprising. Workers — teachers included — are less likely to leave their jobs during a recession, as research from the Great Recession showed.

But that doesn’t mean Michigan teachers won’t leave once the coronavirus recession wanes, especially given that morale plummeted during the pandemic.

“COVID … makes you feel like you’re there by yourself,” said Lincoln Stocks, a teacher at Eastpointe Community Schools and a vice president of AFT Michigan. “And if you want to look out for your interests and be safe, then (people say) you don’t give a damn about the kids. And that’s not true, but that’s how it looks. And we’ve got a lot of people who are very concerned for their safety.” e coronavirus has disrupted many teachers’ work lives, forcing them to adopt new roles and methods — such as online instruction — for which they have little training and which bear little resemblance to the job they signed up to do.

Many teachers feel that they’re not succeeding in their jobs during the pandemic — a major predictor of whether they’ll leave the profession, according to a paper published last summer.

“All of the things that drive teachers out of the profession… are happening at extremely alarming rates right now,” said Nicole Simon, a co-author of the paper and a researcher a liated with the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers at Harvard University.

“My prediction is that we’ll see a mass exodus from teaching.”

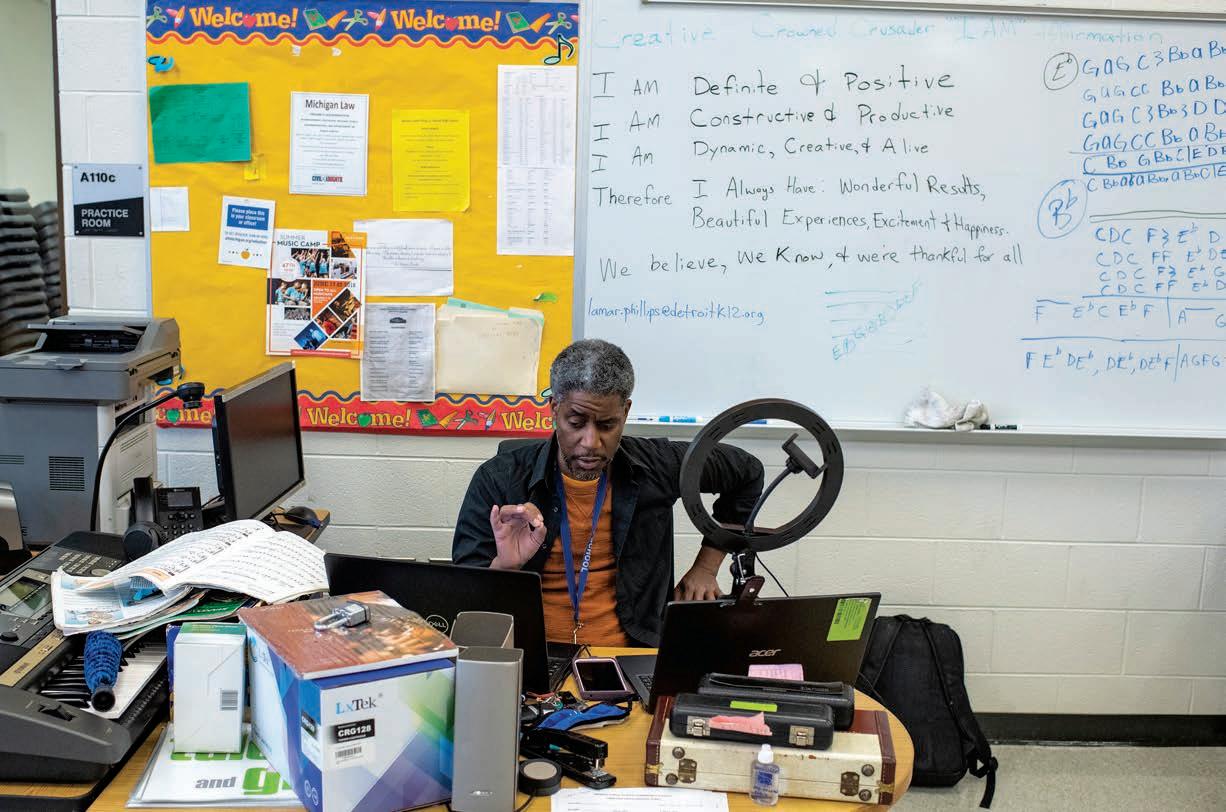

Lamar Phillips, director of instrumental music at Martin Luther King Jr. Senior High School in Detroit, talks with his students over a virtual meeting March 23 in his classroom.

Phillips is in his 26th year of teaching. | NIC ANTAYA FOR CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS

What happens when they leave?

When teachers leave, it interrupts classroom routines and severs relationships with students, parents, and colleagues, killing the essential connective tissue that makes schools work.

“ at instability, it breaks communities — and community is a huge part of how you support students,” said state Rep. Darrin Camilleri, a Trenton Democrat who previously taught social studies at a Detroit high school with high teacher turnover.

In one study of teacher turnover, researchers followed 850,000 New York City students over eight years and concluded that students in schools where many teachers left tended to score lower on English and math tests. e negative e ects were espe-

YB KOBY LEVIN

Too many Michigan teachers want to leave their classrooms. Here’s how that could change.

Michigan has a teacher turnover problem that is limiting the educational opportunities of Black students and those from low-income families.

But it doesn’t have to be this way: Teachers are more likely to stay when they have better training, principals who are well trained, reasonable pay, and when their schools have enough money to hire enough paraprofessionals, psychologists, and social workers.

While major advancements on those fronts would require big changes to Michigan’s taxpayer investment in education, experts point out that some schools manage to buck the teacher turnover trend by making small school-level changes.

Signi cant new investments are suddenly within the realm of possibility, at least in the short term. Despite ongoing gridlock in the state Legislature over school spending, school districts are set to receive billions in federal coronavirus aid, much of which must be spent within several years.

Some advocates say that the money could be used, in part, to pay for training and mentorship that make teachers more e ective — and more likely to stay.

“We absolutely have the ability now to reduce turnover and create greater retention,” said Adam Zemke, executive director of Launch Michigan, a business consortium that advocates on education issues.

Training, coaching and mentorship

Launch surveyed 17,000 Michigan teachers in 2019 and found a widespread sense that they aren’t treated

like members of other American professions — doctors, lawyers, veterinarians.

“ ey don’t feel empowered, they don’t feel like they’re being treated as professionals, they’re not supported,” Zemke said.

Ongoing training, mentorship, and coaching are an essential part of being a professional, Zemke said. Yet surveys show that most teachers nd state-mandated training unhelpful, and research points to a lack of support and mentorship as a key reason that many teachers quit early in their careers.

“It’s about being treated like a professional in any other industry, where that industry does everything it can to help you grow,” said Zemke, a former state representative from Ann Arbor.

Zemke added that there are many good potential uses of the federal aid dollars, and that Launch hasn’t yet made any speci c recommendations about how the money will be spent.

On-the-job mentorship is key to

helping teachers succeed, especially early in their careers, but few receive it.

Several e orts across the state aim to change that. In Detroit, an innovative school models its mentorship program o the “residency” training system used by medical doctors, in which trainees receive support from mentors and from more experienced peers over three years. In Battle Creek, a philanthropic initiative pairs veteran teachers with novices for regular classroom visits and consultations about teaching technique.

ose programs cost money, but districts could jump start their own versions with part of the federal stimulus, Zemke said.

Principals need training and support too, and research shows that an e ective principal plays a crucial role in retaining teachers. e Detroit Children’s Fund, a nonpro t that is investing tens of millions of dollars in Detroit to improve schools, has already paid for principal training programs across Detroit.

But most principals in Michigan don’t get that kind of support, said Nicole Simon, a researcher a liated with the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers, an initiative at Harvard University.

“We know that for teachers one of the most important factors in keeping them in their schools is strong leadership. And we have not invested in that kind of leadership. We don’t teach people how to do it, we don’t support them while they’re doing it.”

—Adam Zemke, executive director of Launch Michigan

A systemic problem

Experts have been sounding alarms for years about cracks in Michigan’s teacher pipeline, pointing out that fewer people are entering teacher training programs and becoming certi ed as educators. Headlines periodically warn of a “teacher shortage.”

“Teacher turnover is only part of the teacher supply chain equation,” said Jack Elsey, executive director of the Detroit Children’s Fund, a nonpro t. “ e percentage of teachers who are enrolling in teacher prep, the number of people going into teaching — all of those metrics scare the pants o me.”

Ask many observers how to reduce teacher turnover, and they will tell you that turnover is merely a symptom of a much larger problem.

Simply put, the state isn’t investing enough in schools, said Barbara Schneider, a sociologist at the University of Michigan who has studied turnover.

“It’s a resource issue,” she said.

E orts to reduce turnover in Michigan have often centered on simply giving teachers more money for their work. When a nonpro t in Detroit pumped millions of dollars into a handful of higher performing charter schools, some of the money went toward retention bonuses. Just last year, the state set aside $5 million for a similar program: new teachers will receive as much as $1,000 for staying on after their rst year, with the possibility of receiving more if they stay on for three years.

But these programs are small in the context of Michigan’s $15 billion annual education budget.

cially strong in schools with more low-performing students and more Black students — who are most likely to attend schools with high teacher turnover.

“It’s just not possible to have a functioning school with” very high levels of turnover, said Ed Fuller, an education professor at Penn State University who helped design a teacher retention policy in Austin, Texas.

Turnover doesn’t just pose academic costs.

Researchers say nding and training new teachers is expensive, especially in hard-to-sta urban areas such as Detroit. ere is no established price tag for teacher turnover in Michigan. But an estimate made by economists in North Carolina, a state with a similar population to Michigan’s, put the cost at $337 million in a single year. at amount of money would go a long way in Michigan: it’s millions more than what Utica Community Schools, the state’s second largest district, spent in total last year.

Experts say that reducing teacher turnover statewide would likely require major new investment in schools. While Michigan’s school spending has ticked up slightly in recent years, overall its spending on schools has declined over the last two decades, adjusting for in ation. e state would need to raise an additional $3.6 billion per year for schools in order to hit adequate spending levels recommended by a nonpartisan education panel in 2018.

An overhaul of school funding, however, would require a tax increase, which would likely be dead on arrival in the current Republican-controlled Legislature.

Rep. Brad Paquette, the Republi-

David Hecker, president of the American Federation of Teachers Michigan, credited Gov. Gretchen Whitmer with pushing the program through, saying it communicates to teachers that they are valued. But he said the amount of money in the program “isn’t going to change anyone’s life.”

By contrast, the amount of money Michigan spends on schools has dropped sharply — it declined 30 percent, adjusting for in ation, between 2002 and 2015 as state revenue for schools was reduced by tax cuts. ere has been only one comprehensive e ort to estimate the cost of adequately educating Michigan’s roughly 1.5 million students. Experts say the state falls more about $3.6 billion short of that mark.

Schneider says increased funding wouldn’t just allow for increased teacher pay, but also for increased funding for schools so that they could pay for improvements that would improve working conditions at schools. More money could pay for decreased class sizes, better teacher training, better learning materials, or for more school sta — paraprofessionals, counselors, and social workers — who give teachers the freedom to focus on teaching.

Public schools in Detroit, Flint, Battle Creek, Benton Harbor and other urban districts see a higher percentage of teacher turnover each year than more a uent districts such as Grosse Pointe, Bloom eld Hills and St. Joseph. This chart shows the percentage of teachers who started in one school district in the fall of 2018 and were no longer working for that district in the fall of 2019.

% moved

Detroit Flint Battle Creek Benton Harbor Bloom eld Hills Grosse Pointe St. Joseph 31 27 24 33 14 12 5

19% Statewide average 81%

SOURCE: MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION; CHALKBEAT DETROIT RESEARCH

% stayed 69 73 76 67 86 88 95

can vice chair of the House Education Committee and a former teacher, is pessimistic about the prospect of any major new funding for schools in Michigan’s current political landscape.

“We have a whole bunch of folks on the GOP side who are like, ‘Hey we’d love to give more money if we’re able to see more return on investment and more innovation in schools,’” Paquette said. “On the left it’s like, ‘We want more investment but we don’t want to change in any way.’”

E orts by the Michigan Department of Education to transform the lowest performing schools — known in Michigan as the “partnership program” — often run aground due to teachers leaving. Turnover is one of the “driving issues” behind the struggles of partnership schools, said Katharine Strunk, a researcher at Michigan State University who co-authored a report on the schools last year.

“You’re trying to turn around your school, maybe buying new curriculum, investing in new training and instructional techniques,” she said. “And you’re kind of wasting your money because teachers are leaving.”

Koby Levin is a reporter at Chalkbeat Detroit. Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee is Chalkbeat’s Washington, D.C.-based data editor.

The big picture is even bigger than you know.

If you think wealth management is only a portfolio of assets that are balanced, diversified, and properly weighted, you’re thinking too narrowly. Because without a broader wealth management strategy that integrates performance with tax planning, trusts, risk management, cash flow, retirement, estate planning, charitable giving, family assistance and so on, ROI only goes so far. Clients of Greenleaf Trust (with over $15 billion in assets under advisement) are nearly always pleasantly surprised that their big picture is even bigger, and better, than they knew. Give us a call and we’ll help you see yours.

Client relationships begin at $2 million.