6 minute read

A City of God and Tameeya

from Going Green

by Dana Slayton

Landing at Cairo International Airport after over a day’s journey from the United States is incredibly disorienting

Advertisement

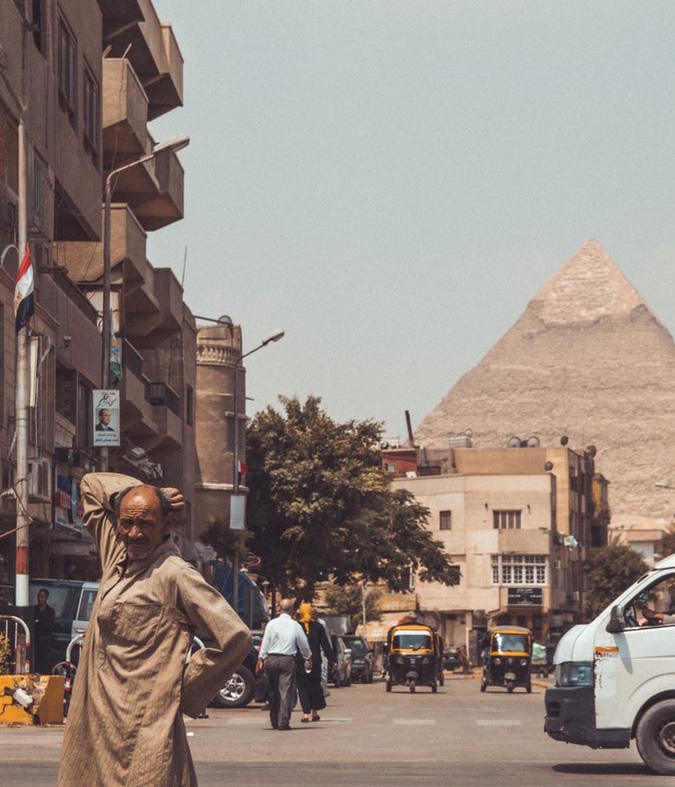

to say the least. There is a peculiar feeling of jet lag-laced dread that permeates the aircraft a few minutes before touchdown. No one is immune. The man sitting beside you stops snoring, glances out the window, and makes some kind of vague, one-word comment about what is about to happen, like, “hm, clouds” or “hm, weather” or “hm, the pyramids” or—perhaps most terrifyingly—just “hm.” Babies start to cry. The dread that hangs heavy in the airplane air moments before landing is nothing more than a stark, sobering appreciation of silence, the last true moments of quiet before Cairo invades us all—mind, body, and soul. When you exit the flight, the “hm, clouds” will become “hm, traffic” as you navigate the claustrophobic chaos of the arrivals terminal to hail a taxi and dive into the fray.

No place on Earth could replace Cairo. There is a special kind of serenity that can only be born when millions of people are living in the same total chaos at the same time. It swaddles the streets in a blanket of collective ambivalence and sings them a lullaby, while car horns and unintelligible shouts of rage hum along. This kind of serenity is only born when all hope for order dies. You cannot afford to be angry that you’ve only moved three feet in the past ten minutes. You make friends with the chaos, and after a while you cease to care that it has been decided you will never make it to your destination. Or that you will make it, but only inchallah (God willing), a statement which means next to nothing once you realize that Cairo traffic probably killed God. But these streets are saturated with divinity. For all its cosmopolitanism, breakneck chase of modernity, and precarious alleyways, Cairo is a holy city.

Cairo traffic tries to kill God, but the Cairene drivers refuse to let him die. He reveals himself in between endless rows of sputtering Toyotas as they inch along the highway, a new brand of the Second Coming announced only by extremely elaborate stickers on grimy windshields that proclaim “Jesus is Lord,” “Remember God,” and “There is no God but God.” He peeks through the gauzy curtains of a barbershop, from his throne of honor atop a mirror with the Egyptian president at his right hand and the Virgin Mary at his left. He sings from the tops of ten thousand minarets in cacophonous unison five times a day.

And when my taxi arrives at the foot of Mokattam Mountain, its engine gasping and choking after a breathless climb through the labyrinthine streets of Manshiyet Nasr—the neighborhood responsible for processing all of Cairo’s waste and consequently dubbed “Garbage City” in Arabic—even the high hills race to claim the ground for God. “Blessed be Egypt, my people,” reads the mountain. The inscription is etched into the rock face in graceful Arabic, like a sticker on the grimy windshield of the city itself. The mountain and the smog are the only things separating Cairo from the heavens here. The mountain, the smog—and the falafel, that is.

If Mokattam Mountain is the bridge that God walks to enter the streets of Cairo, then falafel is the gatekeeper of the city, the intermediary between the heavens and the earth. God would have no standing here without falafel, which is called taameya in Egyptian Arabic. This variation on the street

food classic is ancient, and any self-respecting Egyptian would proudly proclaim that it predates its famous Levantine cousin. While American shopkeepers and Levantine cooks use chickpeas pounded with powdered spice as the base of their fritters, Egyptians use fava beans and fresh vegetables such as leeks and herbs, vibrant shades of green from the shores of the Nile, and smother them in sesame. Huge iron skillets occupy every street corner in Cairo, from the utopian neighborhoods springing up from the desert to house the city’s elite to the unpaved streets leading up to this mountain, crowded with refuse and half-forgotten statues of saints. The fritters follow the footsteps of this city. As Cairo swallows up the verdant riverbed of the Nile, replacing it with endless rows of concrete housing, it leaves traces of its former, untouched, green glory behind in the guise of taameya stands—where ordinary men turn fava beans into fuel for a nation zooming around at breakneck pace. Bite into one, and you will find it to be

the greenest sight for miles, like a memory of the ancient farmland that gave rise to the city itself.

The history of taameya is tied up with the history of God, and nowhere is this more obvious than at the base of Mokattam Mountain. Egypt’s indigenous population, the Copts, still clings to an ancient rite of Christianity despite near-constant sectarian abuse. According to them, God once moved Mokattam Mountain to prove his righteousness to a particularly obstinate tenth-century caliph.. The last remaining Christian monastery in the city is carved deep into the rock here, virtually invisible to the outside world save an occasional glimpse of the Bible verse carved into the mountain face that announces its presence. “Blessed be Egypt, my people,” it proclaims, quoting the prophet Isaiah in the language of the Bible, a book that barely ten percent of Egyptians still read.

When I arrive there, the taameya season is in high gear. Crucially, the Copts lay claim to the world’s first falafel, tracing it all the way back to the practices of their Pharaonic ancestors, and their current religious practice makes the fritters culinarily mandatory. In the weeks before the Coptic celebration of Christmas, Egypt’s last Christians observe a strict vegan fasting diet. Falafel suits this perfectly. They lay claim to taameya in the same way they lay claim to this mountain -- as the last memory of something too beloved to die. Long before the Arab invasions, when the Nile valley was still greener than the falafel produced there, the Copts heated up these same iron skillets during the same long months of fasting. They prayed in this same cave church, high above the burgeoning city, before praying in a church became an act of defiance. They broke bread and stuffed it with these same fried fava beans.

And for over a thousand years, though persecution and poverty have decimated their numbers, the Copts’ history still sits quietly in these streets alongside their God. Taameya belongs to every Egyptian now. But its origins belong to the Copts, and the pharaohs before them. It graces every table with the unspoken memory of a community just as stubborn and casually holy as Cairo traffic, as serenely chaotic as the symphony of millions in every highway of the city, guardians of a history too tenacious to die.

Returning from Mokattam that day, I clunk unceremoniously back to the city center through the chaotic alleys of Manshiyet Nasr, the neighborhood that is one of the last remaining outposts of majority-Christian settlement in Cairo. God glances at you from every corner here, from the words on the mountain above to the icons of martyrs painted on the walls. He hides in the piles of garbage, sometimes, but mostly he glances out from between them, clinging to cars or to paintings or to taameya.