7 minute read

SPANNING HISTORY

A look inside the bridge’s box girder construction before the last section was lifted into place from the Marine Boss barge below.

Advertisement

I N G E N I O U S D E S I G N C R E A T E S BRIDGE’S SLEEK, RIBBON-LIKE LOOK

By LESLIE CRAWFORD

The first concept of a bridge over San Diego Bay to Coronado was a vision by John D. Spreckels right before his death in 1926. Forty years later it had become a reality.

On Jan 19, 1965, Gov. Edmund J. Brown’s office officially announced that the San DiegoCoronado Bridge would be built. The reactions were mixed.

Then Sen. Bob Wilson stated in the San Diego Union on Jan. 20, 1965, that the project “was jammed down our throats and money was handed off.” Two Coronado residents tried to sue to block the sale of the bonds, but their case was denied appeal at the State Supreme Court.

Plans went forward, and the original proposed cost of construction quickly rose from $30 million to $40 million because of Navy requirements. The cost eventually reached $46 million, spouting more controversy.

When the design was finally revealed to the public in 1967, principal architect Robert Mosher said in a San Diego Union story the bridge “would have a delicate, ribbon-like

Concrete towers were designed as arches to reflect the architecture of California’s historic missions.

silhouette that will make it very beautiful.” He went on to say, “Instead of just a crossing, we wanted to make the event of crossing enjoyable. Going across the bridge will be equally as interesting in its 20th-century way as the ferry is. It’s going to be fun.”

“The shape is logical. The graceful curve of the bridge wasn’t put there because it may look

The 90-degree turn mid-span provides enough height for an empty aircraft carrier to clear the bridge.

pretty,” Mosher said in a trade magazine, The General Contractor. The span’s 90-degree turn was necessitated by a Navy mandate of a 200- foot pass-through height and spans set wide enough to accommodate the Navy’s biggest ships. The turn was needed to add enough length to bring the bridge into compliance.

Mosher’s ingenious design achieved a sleek look. He used an orthotropic model enclosing all the girders, joints and stiffeners inside a box girder, a construction method that originated in Germany for shipbuilding during World War II. At the time it was the longest continuous three-span orthotropic bridge in the world. The blue was selected to blend with the sky and sea, using a special paint mixture that would last eight to 10 years.

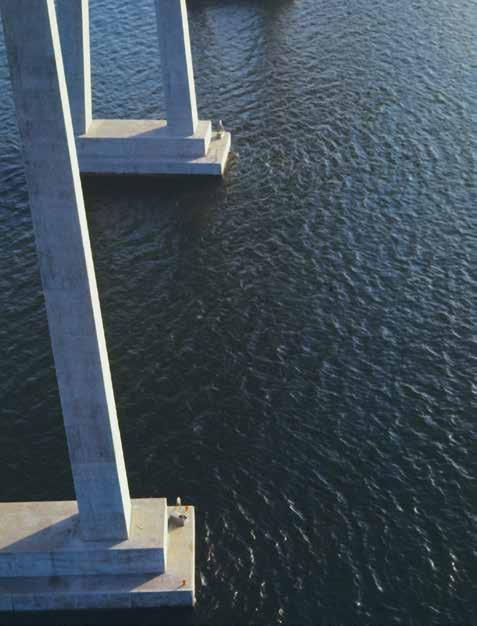

The bridge’s 30 concrete towers were arched, designed to reflect the architecture of California’s historic missions. They rest on 487 prestressed reinforced concrete piles, 54 inches in diameter. Some piles were jetted to depths of 100 feet into the sand and clay beneath the bay.

Mosher was thoughtful about the changes the bridge would bring to Coronado and was concerned the city would become another Staten Island with turnover investors. In a San Diego Union story on June 2, 1967, Mosher is quoted at a joint San Diego Kiwanis Club and San Diego Rotary Club meeting saying, “Coronado must develop a thoughtful, far-sighted plan if it is to avoid this,” urging the City of Coronado to hire a design consultant to help build a master plan.

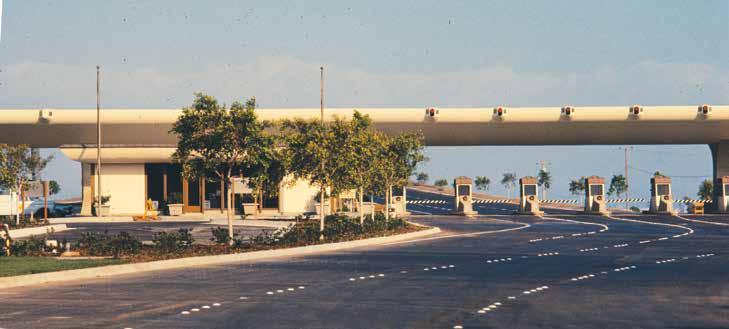

The toll plaza, officially named Glorietta Plaza, was sited on the Coronado side because land acquisition on the

San Diego side was much more expensive and the logistics of collecting tolls from the freeway more complicated. It was placed right in the middle

of Coronado Golf Course. The project required 1.4 million cubic yards of dredge from the bay to fill in the bridge approach and reconfigure the shoreline of Glorietta Bay to add back the lost golf course land.

Construction began in February 1967. Guy F. Atkinson was the contractor, Murphy Pacific Corp. was the steel subcontractor and H.G. Fenton Materials Company provided the ready-mix concrete,

Henry Hunte, grandson of the founder of H.G. Fenton, was a salesman for the company that provided all the concrete used in the underwater foundations, columns, structure and paving. “My responsibility was to ensure that our company was providing adequate service. It was a great project,” Hunte recalled.

A station on the Coronado side mixed the concrete, which was then loaded into big buckets onto old Navy barges. As construction started, piles were driven 100 feet into the bottom of the bay. The sound of the pile drivers could be heard for miles all day long for months — a slow ka-chunk, ka-chunk, ka-chunk.

Hunte’s mother was born in Coronado and he credits Elisha Babcock with giving his grandfather a good start in business in the early 1900s. Fenton also worked on the seawall on Ocean Boulevard.

Murphy Pacific, the superstructure contractor,

BRIDGE AT A GLANCE

Length: 2.12 Miles Grade: 4.67 Percent Highest Point: 246 Feet Vertical Clearance: 200 Feet Support Towers: 30 Channel Span: 1,880 Feet Opened: Aug. 3, 1969 Cost: $ 47.6 Million Toll: Discontinued June 27, 2002 Traffic Lanes: 5 With Reversible Middle Lane

fabricated and assembled the steel box girders in San Francisco, then dismantled them and loaded them onto a barge named Marine Boss, whose deck was the size of a football field. The barge was towed down the coast to San Diego Bay where everything was reassembled. The boom on Marine Boss had to be lengthened to 290 feet to handle the monumental job of lifting the box girder sections — which were up to 96 feet long and weighed up to 215 tons — into place.

The final span was placed on May 28, 1969. Coronado Mayor Paul Vetter was invited to be part of the informal ceremony and signed his name on the metal plate at the edge of the girder. (Contrary to popular belief, the center span was not designed to float.)

As the bridge neared completion stormy weather in the spring delayed opening day. Finally, the big day arrived with opening ceremonies on Saturday, Aug. 2.

Gov. Ronald Reagan was among the many dignitaries who participated in the celebrations. Reagan unveiled a plaque and officially dedicated the bridge. The ribbon cutting was done by Vetter and San Diego Mayor Frank Curran. The rest of the day was a celebration, with free rides to the top of the bridge in double-decker buses and in three Navy LARCs (amphibious vehicles) from Naval Amphibious Base.

At the stroke of midnight, the bridge opened for traffic. Toll was set at 60 cents each way, with a reduced fee of 45 cents with a pack of 50 tickets

Once the bridge was open, Coronado began to live with the consequences of more traffic. The speed dip at 3rd Street and C Avenue — eventually redone to be less severe — was a repository for hubcaps, bumpers, license plates and other car parts as cars raced off the bridge and up 3rd Street. Traffic increased exponentially, far beyond what was predicted. In 1964, Coronado ferries had carried over 3.4 million vehicles across San Diego Bay. The bridge saw more than 2 million cars in the first 3 months of operation.

As with all construction projects, there were still things to be completed after the opening. By April 1970, lighting was installed. And access to and from South Bay was added by 1973. In 1976, the bridge was retrofitted with special rods to protect against earthquake damage. And in April 1993, the movable barrier called the Zipper debuted.

The bonds for the bridge were paid off in 1986, much faster than the original 40-year plan, but the toll remained until June 27, 2002. The final toll was collected from David Lisl of El Cajon, ending 33 years of fees.

The bridge was a big adjustment for the community, but the reality was that the ferries simply could no longer handle the vehicular load efficiently. After 50 years, the bridge has become an integral part of the fabric of Coronado.

And Mosher was right. He did make the crossing enjoyable.