GUILLERMO GALINDO SONIC MEDIATIONS

Sonic Mediations represents a chance to view the extensive and important work of Guillermo Galindo. An experimental musical composer, performance artist, sonic architect and visual artist, Galindo breaks down tra ditional barriers between the mediums. His artistic practice is a cross between sound, sight, and performance, merging these art disciplines while exploring humanitarian issues, politics, society, and spirituality.

Guillermo Galindo was born in Mexico City where he completed a BA in graphic design and studied musical composition at the Escuela Nacional de Musica. He then attended Berklee College of Music, earning a BA in film scoring and composition. Galindo went on to receive an MA in composition and electronic music at Mills College in Oakland, California. During his studies he became inspired by western experimental composers as well as Latin American artists.

Although Galindo began his career writing more traditional Western classical music, he began composing exper imental music in 2006. He also began constructing his own instruments with found items, cyber-totemic sonic objects. He used these in his improvisations and performances, often including the audience in his compositions.

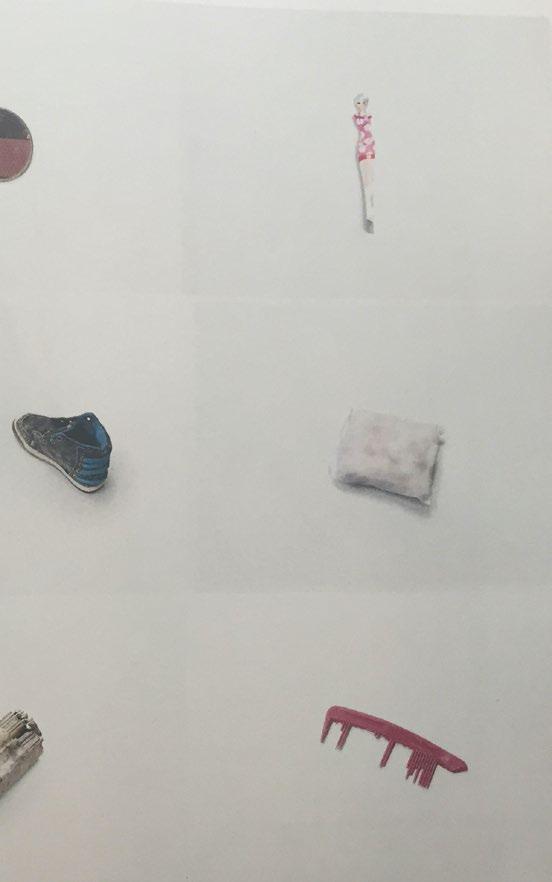

More recently, he has been creating his instruments with objects left behind by immigrants and border patrol. Each object has a history and emits a unique sound reflecting the materials it is made of and its overall shape. These objects become a source of healing as well as a bridge between the material and spiritual realms.

Galindo’s graphic scores and three-dimensional sculptural cyber-totemic sonic objects have been exhibited and performed internationally. He currently teaches at the California College of Arts in San Francisco and has also been invited as a Mohr Visiting Artist at Stanford University (2018). Galindo was also a resident artist at Vanderbilt University as well as a Thomas P. Johnson Distinguished Visiting Scholar (2019) at the Rollins Cornell Arts Museum. He has also been a recipient of the Fleishhacker Foundation Eureka Grant.

I am very honored and excited to exhibit Guillermo Galindo’s work for others to enjoy. I would like to extend my gratitude to the many colleagues that have been instrumental in making this exhibition possible- Guillermo Galindo for the opportunity to exhibit his remarkable work; Kory Twaddle, Gallery Assistant, for organizing and arranging the show details; Brad Peatross of the School of the Arts, California State University, Stanislaus for the catalog design; and Parks Printing for the production of the catalogs. I also want to express my appreciation to the Instructionally Related Activities Program of California State University, Stanislaus, as well as anonymous donors for the funding of the exhibition and catalogue.

Ellen RoehneInterim Director, University Art Galleries

California State University, Stanislaus

Most of my college and graduate music education consisted on learning and analyzing European com position techniques from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. While studying music composition and theory, my teachers were part of a genera tion of composers immersed in the, then prevalent, European and American Avant Garde styles. Their aesthetics were based on musical tendencies that developed in Europe and the USA during the late 20th century.The work of composers such as Gyorgy Ligeti, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Milton Babbit and Krzysztof Penderecki and the the ideas of the late integral serialists such as Arnold Schonberg an Alban Berg defined the stylistic examples to be followed by all composition students at that time.

The instruction in the visual arts was not different from that one I was experiencing in my music composition courses. While studying graphic design I took courses on “History of Art” which meant the exclusive history of European visual aesthetics. The examples to follow, in this case, were connected to European and American graphic design and the visual styles, at the moment, were 20th century’s abstract expressionism, conceptualism and minimalism.

While I enjoyed learning and finding my own approach to the European and American Avant Garde movements, I was also alternatively inspired by the the music of Latin American composers such as Alberto Ginastera, Julian Carrillo and Silvestre Revueltas and popular musicians such as Maria Grever, Agustin Lara, Astor Piazzola and Damaso Perez Prado. I was also motivated by visual artists such as Tarsila do Amaral, Remedios Varo, Mathias Goeritz, Enrique Chagoya and films makers such as Luis Buñuel, Werner Herzog and Alejandro Jodorowsky. At that time, my connection to American black music, rock, jazz and blues was also integral to my daily life. Unfortunately any information of non European musicians and artists was hard to find and, obviously, not part of our official studies curriculum.

The influence of concepts and ideas of such Latin American and Afro Caribbean artists provided me with the fundamentals of acquiring a possible alternative language which would combine all of my knowledge and eventually act as a viable counterpart to the colonialist prevalent hegemonic and rationalist Western aesthetics. The research I did while writing my first orchestral piece Ome Acatl (1996) based in the symbolism and pro portions of the Aztec Calendars made me aware of concepts of time and space present during pre-Colombian times. Non-Western religious, social and ritualistic practices present in Afro Caribbean and native American cultures also had a big influence in my own performance and visual art practices.

Eventually I start conceiving my own music and performance exercises as community based rituals rather than “concert music” interpretations. It was essential for me to establish a reciprocal and horizontal connection with my physical and temporal environments, my audiences and my musician(s) as witnesses or/and participants rather than just passive receivers.

In 2006, I began to create sonic devices out of daily life objects. I found that each and every object that sur rounds us has a particular sound present in each of our personal daily realities. The sound of any object is unique to its shape, context and physical materiality. Each object surrounding us holds a symbolic meaning and belongs to a specific context within our lives.

For my series Border Cantos (a collaboration with photographer Richard Misrach and following my participa tion in documenta 14), I designed more than 60 sonic objects and musical scores from immigrants personal belongings and from the border patrol apparatus.

Every object had a history and an association with a particular ecosystem and told the story in its own voice and from its unique perspective. I conceive my Cyber-totemic sonic objects as talismans, connectors or media tors between alternate realities that act as bridges between the material and spiritual, between reality and imagination.

Every sonic object is unique and tells the different story about human experiences. A prosopopoeia that allows things to tell the story with their own unique voice. The multiple sound combinations of my sonic objects has become part of a large personal sonic vocabulary. I consider each of my sonic devices a powerful vehicle to heal and address imperative spiritual, political and social justice issues.

Ecco Exodus documenta 14, immigrant sonic devices. immigrant plastic bottles 10” x 19” x 4”, 2017

Many of my instruments are one of a kind. Others are derived from designs that already exist in different cultures. Because of the heterogeneity of the materials they are made from, their sounds cover a wide range of different and interesting tones and pitches. All of them, in one way or another, offer me opportunities to discover new sounds and invent performance techniques. When designing instruments, my goal is not to obtain the perfect or most beautiful sound, but to allow the materials to sing in their own voices. There are many reasons why I refuse to consider my pieces recycled art objects. The instruments for the Cantos project are meant to enable the invisible victims of immigration to speak though their personal belongings. Using their own narrative, these instruments tell us imaginary stories about places and people that may or may not still be alive. Other instruments for this project came from the apparatus of division itself. These objects of aggression were also given a new life and an opportunity to speak in their own terms.

During my process I followed primordial and universal traditions. Nothing that we found in the terrain was excluded. All of the objects were part of a carefully crafted, complex landscape that comprises the border.

In the pre-Columbian world, there was an intimate connection between an instrument and the material from which it was made. For pre-Columbian cultures, there was no separation between the spiritual and the physi cal world. Mesoamerican instruments were talismans between worlds, and the sound of each instrument was never separate from its essence, its origin, or its meaning in the world. When the Aztecs were conquered, Spanish Catholicism merged with the old Mesoamerican traditions and incorporated older European practices, including the veneration of relics (from the Latin word reliquiae meaning “remains,” or from the verb relinquere, meaning “leave behind”). Relics consisted of clothing, personal objects, or any physical remains of a spiritual leader or saint to be worshipped after death. Similar practices incorporating objects belonging to ancestors existed in Buddhism and Hinduism.

Afro-Caribbean musical tradition incorporated the daily objects discarded by slave owners into musical instru ments. Clay jars that once held olive oil were covered with shells to make the “shaker” called shekeré The wooden boxes that brought goods from Europe became the percussion instrument known as cajón and a couple of spoons hitting against each other became an instrument still used in carnival music today. The tradition of reutilizing disposed objects and giving them alternative uses has been around for many years. Reappropriation, renaming, and reusing have always been important strategies for cultural survival for the conquered and oppressed. Imagining the world and recreating it in one’s own terms is the first step for selfacceptance and liberation.

For Chicano artists, the survival practice of mending and making things last longer was turned into the modus operandi underlining the nonlinear, exploratory, and unsolemn vision of Rascuachismo (a word of Nahuatl origin) Rascuachismo is a “nonintellectual, visceral response to the ‘lived reality’ of the underdog where ‘things are not thrown away but saved and recycled often in different context (e.g., automobile tires used as plant containers. Plastic bleach bottles becoming garden ornaments . . .),” writes Tomás Ybarra-Frausto.

All of these personal objects from immigrants now have a second life as musical instruments. They are the evidence of an ongoing human tragedy that is happening before our eyes. These musical objects sing to us about their invisible owners.

A musical score can be defined as a set of codified symbols written on a piece of paper or any other readable surface, to be translated into sound events to be reproduced in real time. For many years, my interest in the evolution of musical scores, particularly those written in the last half of the twentieth century, has turned into a fascination with symbolic language, visual data, codification, and the interpretation of arrays of data into other media.

In the twentieth century, traditional Western notation broke from the limitations of the five-line staff. Traditional ways to indicate pitch, dynamics or volume, duration, placing of events in time, tempo, and many other param eters had to accommodate new ways to conceive and perform music. These scores allowed broader options, both for instrumental interpretation and for visual experimentation. The creation of new music symbols, often invented by the composers themselves, made it common practice to include a key explaining the symbols in the first pages of each score. Many symbols were later standardized and became more familiar in composers and performers’ repertoires, alike. Nonlinear and modular scores allowed the composer to express new ideas and alternative ways of looking at graphic representations of real time, thus allowing the performer a better understanding of the concepts behind the score and even alternative choices for interpretation.

The score for John Cage’s Variations II (1961), in which physical measurements are translated into musical events, consists of eleven transparent sheets: six lines and five points to be arranged randomly. Perpendiculars are dropped from points to lines to determine sound characteristics. In the 1970s composer Iannis Xenakis completed the UPIC (Unité Polyagogique Informatique CEMAMu), a computer-aided graphic design tool for composers. By the 1980s, graphic scores had evolved so much that composers such Sylvano Bussotti and Earle Brown nearly blurred the lines between music and visual art.

Looking back in history, graphic music notation is as old as the need for humans to express ideas with symbols. Cuneiform tablets found in today’s Iraq, dating from 2000 BCE, represent fragmentary instructions on how to perform music. The Aztec and Mayan pre-Columbian codices (Mexihcatl qmoxtli) were iconographic maps of elaborately detailed histories of events meant to be read in sequence and in very specific ways. Codices were a poem, a song, a story, a painting, and a detailed account of objects and food present at a particular scene, at a particular time—all in one.

The first time I saw Richard Misrach’s photograph of a Border Patrol tire drag, with the lines on either side of a sandy desert road, I thought about diagonal staff lines in motion, pulling the viewer into the picture and/or the listener into a sonic sequence. From the beginning I thought of the process of translating the data in the pho tographs into scores, in the same way that a computer converts arrays of zeroes and ones into pictures, music, or words. In my scores I also tried not to exclude the emotional elements, the narrative and the archetypal symbolism: people behind bars, a flock of birds, an empty sky, a surveillance tower, gun shells, etc. Translating photographs into scores also allowed me to challenge the traditional Cartesian tradition of reading music from left to right. These photographs inspired me to think of unexpected events coming from all directions all at once or at different times: a polycentric universe where anything can happen at any given time.

In Richard’s photographs of the Border Wall, the thick vertical bars looked like a musical grid where everything seemed to be carefully placed. I also thought of patterns and microscopic codes in the texture of the Wall, some of them like invisible holes where people could come through. A photograph of an abandoned sarape reminded me of the codes and stories recorded on the textiles of ancient weavers. The colors, the fog, and contrasts of daylight at dawn made me think of bright musical passages moving into the opaque. The density of the landscape or the curvature of the mountains became melodic contours. The composition of each pho tograph made me think of alternative ways of reading the music. The human-shaped targets had ruptures that suggested overpowering deliberate gestures, and the lines in the ammo packages became musical pathways. Official documents regarding the construction of the Wall became structural designs. Large Excel documents provided by the Colibrí Center, listing the precise coordinates of where bodies were found in the desert and the possible causes of death, were translated into symbols that can be interpreted as music. Text data about the disappeared was converted into scientific formulas, Braille code, and guitar tablature, and superimposed onto Richard’s photographs, creating musical patterns that merged with the elements present in the visual composi tion. The Braille code was printed on a large paper made from immigrants’ clothing. Following the tradition of Aztec banners (pantli) used to establish territory, I also printed musical scores onto discarded banners used by humanitarian groups to mark the locations where water is strategically placed for immigrants traveling through the desert.

Translating photographs into events in time reminded me of the conception of space and time by Mayan and Zapotec artists, as described by Octavio Paz, where “space is fluid . . . and time is solid: a block, a cube. Moving space and frozen time: become two extremes of the cosmic movement.”

Reprinted with permission: Imaginary Stories which was originally published in my and Richard Misrach’s Border Cantos book published by Aperture.

Es-pray, 2017, courtesy of the artist, photograph by Richard Misrach..

Tonk, 2015, courtesy of the artist, photograph by Guillermo Galindo

Transonic, Qualia Gallery, Palo Alto, California, (July 2022)

Native | Non native | Supernatural, S/A Exhibitions, Santa Ana, California (Nov 20, 2021–Feb 20, 2022)

Two Spirit Release, Lux Art Institute, San Diego, California (June 19–Aug 4th 2021)

Sonic Biogenesis: Genomics and Mutant Jungles, Beacon Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts (Feb 5–Mary 2, 2021)

Border Cantos/Sonic Borders, Art Bridges (Guillermo Galindo/Richard Misrach)

Ashland Art Museum, Ashland North Carolina, (October 2022)

Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa, (Feb–June 5, 2022), Southern Utah Museum of Art (July 31–Oct 15, 2021)

Westmorland Museum, Greensburg, Pensylvania (May 30–Aug 22, 2021),

Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York (Feb1–May 9, 2021)

Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, North Carolina (Oct 1, 2020–Jan 4, 2021)

Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University Lewisburg, Pensylvania, (Jan 15–Mar 24, 2019)

Missoula Art Museum, Missoula, MT (May 28–Sept 19, 2019)

Amarillo Museum of Art, Amarillo Texas (Aug 10–Oct 28, 2018),

Cyber-totemic Objects and Sonic Mediators, Center for New Music Window Gallery, San Francisco, CA, (Sept 30 - Oct 30, 2019)

Sonic Botany, Getty’s Pacific Standard Time, Huntington Library, Pasadena California (Sept 2017–Jan 2018)

Border Cantos, Richard Misrach| Guillermo Galindo

San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose California (2016)

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas (2016)

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (2017)

Pace Gallery, New York (2017)

Sight and Sound, Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, Santa Cruz, California (2015) Obscuras Fronteras, Skyline Gallery, San Bruno, CA (2012)

Sonic Terrains in Latinx Art Vincent Price Art Museum, Los Angeles (April–July 2022)

Mapping the Sublime: Reframing Landscape in the 21st Century, Brand Library, Glendale (April–June 2022)

Vida, Muerte, Justicia | Life, Death, Justice, OCA Center, University of Utah at Ogden (October–November 2021)

The Myth Industry: Friends Indeed Gallery, San Francisco, CA (March 5–Apr16, 2021)

La inutilidad feliz del artista, (collaboration with Carlos Amorales) XIV FEMSA Bienale, Colegio Jesuita, Michoacan, Mexico (Dec 1–Feb 7, 2021)

Dissonant Matters (group exhibition) Kala Art Institute, Berkeley, CA, (Sep 24, 2020–Jan 23, 2021)

La inutilidad feliz del artista, (collaboration with Carlos Amorales) XIV FEMSA Bienale, Colegio Jesuita (Dec 1–February 7, 2021)

En Medio | Senses of Migrations, The John and Geraldine Lilley Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada, (June–Oct 2021)

The Musical Mind at The Highline New York. (Apr 30, 2020–March 31, 2021)

When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, (traveling exhibition)

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston MA (October 23, 2019–Jan 26, 2020)

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis MN (Feb 22–May 24, 2020)

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford, CA (Feb 5–May 31, 2021)

Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, CA (March 27–July 31, 2020 )

How The Light Gets In. Migration In Contemporary Art, (group exhibition), Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, (Sept 6–Dec 8, 2019)

The Warmth of Other Suns, The Phillips Collection Washington D.C., (June 22–September 22 , 2019)

Perilous Bodies,The Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice, New York (March 5–May, 11, 2019)

El Dorado: USMexico Border. Place Imagination and Possibility, Lilley, France, (April 27–July 28, 2019 )

Big Orchestra, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt ,Germany (June 19–September 8, 2019)

The Place as Metaphor: Collection Conversations, (January 19–May 12, 2019)

This Land, Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco, California (June 1 2018–April 30, 2019)

Monarchs: Brown and Native Contemporary Artists in the Path of the Butterfly” (traveling exhibition) Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas, (March 7, 2019–June 2, 2019)

MOCA (Miami) (May 24 - Aug 5, 2018) , Bermis Center, for Contemporary Art, Omaha, NE (Dec 2017–Feb 2018)

The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility (group exhibition)

CAFAM (as part of Pacific Standard Time) Los Angeles California (September 2017–January 2018)

516 ARTS Albuquerque, New Mexico, (January – April 2018)

Vision and Voice (group exhibition)

Art Ark Gallery, San Jose California

Chandra Cerrito Contemporary Art Oakland, California (2017-2018)

Drawn from a Score, Beall Center for Art and Technology (group exhibition), Irvine California, (October 2017- Feb 2018)

Seeking Civilization: Art and Cartography, (group exhibition) Wendy Norris Gallery (2017)

Mapping the Uncharted (group exhibition), RIchmond Art Center, Richmond, California (March - May 2017)

Shadow and Space (group exhibition), Thoma Foundation Orange Door Chicago (2016).

Différance Le Laboraitoire Galeria, (group exhibition) Mexico City (2015)

Electronic Pacific (solo exhibition), SOMarts Gallery San Francisco art Institute, San Francisco, California, Beijing (2013)

Other Minds Music Festival, San Francisco (2022)

XIV FEMSA Bienale, Mexico (2021)

Art Basel, Miami, Fl. (2019)

FIAC, Paris, France (2018)

Getty Museum, Pacific Standard Time, Los Angeles (2017)

Documenta 14, Athens, Greece, Kassel, Germany (2017)

CTM Festival, Berlin, Germany (2017)

Germinal Music Festival, Mexico City (2014)

San Francisco Electronic Music Festival (2012)

Radar Music Festival, Mexico City (2009)

DeYoung Museum, San Francisco, California

National Gallery, Washington DC

LACMA, Los Angeles, California

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Thomas Foundation Art Museum, Santa Fé, New Mexico

Rollins Museum of Art, Winter Park, Florida

Remote Control, (2016-2017) Kronos Quartet, Fifty for the Future Project, performed at the Highline, New York and at the San Francisco Jazz Festival (2017)

Blood Bolero (2014) Amy X Neuburg and the Paul Dresher Ensemble Peces (2014) (for chamber ensemble and video), Ensable Luminico Espacios Mercado Sonora (2015) (for chamber ensemble) Bernal Hill Players

Voces del Desierto, Quinteto Latino (2011-12) (wind quintet with sonic devices made from immigrant’s belongings) Trade Routes, Oakland East Bay Symphony Orchestra and choir (2006), (spoken word devorah Major). Post_Colonial Discontinuum, Earplay Ensemble (2006-07) (for MAIZ cyber-totemic sonic object)and chamber ensemble) OME ACATL (1996) (orchestral work), OFUNAM Orchestra, Mexico City

Decreation/Fight Cherries (2001), (text by Anne Carson)

Califas 2000 (Jurassic Aztlan) (2001-2004) (opera in collaboration with performance artist Guillermo Gomez Peña) Publications and writings about Galndo’s work: Resonant Matter , Lutz Koepnick (2021) Bloomsbury Academic Press

Talking Trash: Cultural Uses of Waste (2019), Maite Zubiaurre Vanderbilt University Press

When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, (2019) Exhibition Catalogue including a conversation with Josh Kun, Yale University Press

Border Cantos (2016) RIchard Misrach| Guillermo Galindo, Aperture Foundation

Variacion de Voltaje (2013), Conversations with Mexican Electronic Composers FONCA/ Claustro de Sor Juana. Mexico CIty À la recherche de Pierre Schaeffer. Portrait(s) (2013) Editor: Caroline Grivellaro Memoire de Mondes/CMAS, Paris France (2014)

CONACULTA /CMAS Mexico

MAIZ (2007) Cybertotemic Instrument MIT Leonardo Music and Science Journal

Mohr Visiting Artist, (2018) Stanford University

Thomas P. Johnson Distinguished Visiting Scholar (2019), Rollins Cornell Arts Museum

California College of Art /Senior Adjunct professor (2000-2022)

Diversity Studies Department, Video and Performance Department, Humanities and Sciences Department and Graduate Deign Department Education

Master in Arts (1991) Music Composition and Electronic Music, Mills College, Oakland, California

Bachelor in Arts (1989) Film Scoring and Composition,, Berklee College of Music Boston, Massachusetts

Graphic Design (1987) Bachelor in Arts, Universidad el Nuevo Mundo, Mexico City

Bachelor in Arts (1987) Music Composition, Escuela Nacional de Música, Mexico City.

Indian Music (1995), Ali Akbar School of Indian Music, Marine County, CA

Sonic Borders vol. 1.1 (3 vinyl set) (2021), audio of sound installation. Red Culebra, 4 Cycles + One (2021) electronic duet with Cristobal Martinez Espacios Mercado Sonora (2017) (for chamber ensemble) Bernal Hill Players LIFT (2009) (CD audio collaboration between Guillermo Galindo [MAIZ] and violist Charlotte Hug Edgetone Records, California México Electrocustico: An anthology of the history of electroacoustic music in Mexico 1960-2007 (2008), CONACULTA, Mexico Virus Sonoro, Anthology of 20, 20 second pieces for random radio broadcast (2007) Radio Ibero, Mexico, En Busca del SIlencio/Escorpión en Ascendente (2007), (rearrangements of Juan Jose Gurrola’s neuro atonal album), Memento: Mexican composers and poets, (2006), Instrumenta, Mexico City, Sn_d (2005) (sonic ambiances by Gal_in dog*)

Luminous Fissure/ North PacificMusic Oregon. San Francisco, Transmission Tenderloin (2005) (in collaboration with Chris Brown), Tzadic, New York. Revista de Arte Sonoro #4 (2005), Maiz recording, Centro de Creación Experimental, La Mancha Spain. Back in LA, Erratum Sound Review (2004), (in collaboration with Guillermo Gomez Peña), Art and Noise Erratum Musical, Paris Sound Site CD (2004) Triangle Gallery, San Antonio Texas, Haiku II (2002) (for flute and recorded ambiance, performed by Alejandro Escuer), Aqua Quindecim/Fonca, Transformaciones Mexican and Argentinan 20th Century (2002)

Valentina Cubista (for piano and recorded ambiance), piano Oscar Cano Urtext. Quiet Places A Sound Walk Across Natural California (2001)

Inner Coats Ranges mix collaboration by Guillermo Galindo and biologist Paul Matzner, Oakland Museum of California Kiyohime (1997) (electro-acoustic Dance Suite) Luminous Fisssure/ North Pacific Music, Oregon

Border Cantos: http://bordercantos.com/ Art in America: https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/guillermo-galindo/ Brooklin Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2019/06/music/Guillermo-Galindos-Songs-of-the-Border

The new Republic: https://newrepublic.com/article/132220/requiem-border-wall

The Artery: https://www.wbur.org/artery/2019/10/28/ica-border-wall-migration-exhibition

California Sunday Magazine: https://story.californiasunday.com/richard-misrach-border-signs Hyperalergic: https://hyperallergic.com/394331/richard-misrach-and-guillermo-galindo-border-cantos- pace-2017/ Orlando Weekly: https://www.orlandoweekly.com/orlando/mexican-artist-guillermo-galindobrings-his-sonicborders-project-to-rollins/Content?oid=24399818

The Misoulian: https://missoulian.com/entertainment/out-and-about/a-broken-landscape-andbridgedcultures-in-border-cantos/article_087ef1c0-d5bd-5c84-9a1e-69939f892d40.html

KQED: https://www.kqed.org/arts/11301274/guillermo-galindo-border-cantos-instrumentsinterview Numberic: http://www.numberinc.org/interview-guillermo-galindo-the-sonic-mediator/ Hyperalergic: Hyperalergic: https://hyperallergic.com/394331/richard-misrach-and-guillermo-galindo-bordercantos- pace-2017/ Reuters India: https://www.reuters.com/article/germany-life-documenta-kassel/from-parthenonof-bannedbooks-to-pipe-homes-of-refugees-documenta-14-kicks-off-idINKBN18Z2JZ

Dr. Ellen Junn, President

Dr. Kimberly Greer, Provost/Vice President of Academic Affairs

Dr. James A. Tuedio, Dean, College of the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences

Martin Azevedo, Associate Professor, Chair

Tricia Cooper, Lecturer

Dean De Cocker, Professor

James Deitz, Lecturer

Daniel Edwards, Associate Professor

Patrica Eshagh, Lecturer

Jessica Gomula-Kruzic, Professor

Daniel Heskamp, Lecturer

Chad Hunter, Lecturer

Dr. Carmen Robbin, Professor

Ellen Roehne, Lecturer

Dr. Staci Scheiwiller, Associate Professor

Susan Stephenson, Associate Professor

Jake Weigel, Associate Professor

Mirabel Wigon, Assistant Professor

Alex Quinones Instructional Tech II

Kyle Rambatt, Equipment Technician II

Dean De Cocker, Director

Kory Twaddle, Gallery Assistant

Brad Peatross, Graphic Specialist II

Guillermo Galindo - Sonic Mediations

October 17–December 20, 2022 | University Art Gallery, California State University, Stanislaus

100 copies printed. Copyright © 2022 California State University, Stanislaus • ISBN 978-1-940753-73-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the publisher. This exhibition and catalog have been funded by Associated Students Instructionally Related Activities, California State University, Stanislaus.