22 minute read

Building a Business rooted in Indigenous Values

Tanka bar

dawn Sherman (Lakota, Shawnee, and Delaware Tribes) is the CEO of Native American Natural Foods LLC, home to the Tanka brand, a B-corp minority certified owned and minority-led company. Recently, Cultural Survival’s Indigenous Rights Radio Producer, Shaldon Ferris (KhoiSan), spoke with Sherman.

cultural survival: tell us how tanka came to be one of the most recognized native american-owned brands.

dawn sherman: Native American Natural Foods was built out of the Pine Ridge Reservation, which is the people of Oglala Lakota. It was built out of the community from the ground up by two grassroots members and social entrepreneurs, Mark Tilsen and Karlene Hunter, in 2007. Tanka was the first product of its kind and it was based on a timehonored recipe that our ancestors have used (and still use to this day) called wasna. This traditional recipe was modernized by the founders and the Tanka bar was made. The bar itself is tender, savory, and sweet, and the mouthfeel that you’re getting is from the 100 percent bison. It also has tart, sweet cranberries in it. It is a blend of taking the fruit, which has high acidity, and the meat and preserving it. It’s a natural process that we used to preserve meat throughout the months in the winter to sustain us.

cs: what are the indigneous values and principles that the company was built and operates on?

ds: In our community, bison is what we call “our sister nation.” It’s a sacred animal and we were actually born of the buffalo. There’s a sacred place in the Black Hills—we were born from that area within this cave. When we first were born, we actually came out as the four-legged, which was the buffalo. As the rest of our people came out, they stayed people, but we were told to follow the buffalo, that they are our life giver. There’s that direct correlation, because they provide our food, they provide our housing, they provide our clothing, and our economy. They sustained us.

Everything we do is to honor the buffalo. The first buffalo that was harvested with Tanka bar was donated by Parks and Rec on our reservation. It was killed ceremoniously and it was all done in prayer. Everything that we do as Tanka and ourselves comes from that creation story, because it’s always honoring the animal. We were told at the beginning of Tanka in prayer that as long as we honor the buffalo, we’ll be successful. We always instill those Indigenous values—taking care of the animals. We’re stewards, you know, we have to take care of them. And the environment. And the Earth.

Our values, especially on the Pine Ridge Reservation, are in Lakota. There are seven values that are taught throughout our generations from the elders, passed on through our families and throughout the community. These seven values are praying; respect; caring and compassion; honesty and truth; generosity; humility; and wisdom. Those are seven of the values that we really are built on and practice. The company was built from the community on the reservation in South Dakota, so those same values were embedded in the core value of Native American Natural Foods/Tanka. They are part of our company culture and who we are.

cs: tell us about the process of manufacturing a tanka bar.

ds: From an operational standpoint, it takes nine hours to make a Tanka bar. It is a full day, it’s carefully made. As you take the ingredients and they’re blended together, they’re formed into what you see as the bar, and then that bar is slowsmoked throughout the day. As you’re seeing that, you can imagine that bison and the cranberries and everything being mixed together and formed and then smoked. And then what comes out of that is that tender, sweet, smoky flavor.

A “day in the life” of a Tanka bar is actually more than one day. Once it gets made, it gets packaged and shipped to our distribution centers. All of this is managed by our employees. We have several employees on and near the reservation and throughout the United States, so our staff members are making phone calls, making sure everything’s getting shipped in on time to our warehouses. And from there, when our customers order it, our staff members are making sure that that’s fulfilled and shipped out on time to our customers.

The nice thing is, operationally, we’re a distance-neutral company. Because we come from an isolated area, you’ll have all the advantages and disadvantages that come from being so isolated. Making sure that we’re able to service all the communities in the United States is really important. A day in the life of operations, it’s done throughout the Nation itself, because for Indigenous communities there are no borders. We’re trying to service all communities. It starts with making a bar in one day, and then it takes another day to get it out and shipped, and then out to our customers so they can enjoy our quality product.

cs: how do you source your ingredients?

ds: We’re really careful about where we source our ingredients. We try to stick to Native American-produced ingredients because it’s more sustainable using Indigenous knowledge, and the buffalo is a sacred animal and a sustainable, regenerative food. Wild rice from the Red Lake Nation is in our sticks. You have the bison, which is prairie-fed, 100 percent buffalo, non-GMO organic. Our spices and our cranberries are organic or non-GMO, and we’re gluten free and USDA certified.

cs: the company has weathered some ups and downs, especially related to financing and investment. how have you dealt with these challenges?

ds: Being in the food industry, we know that it requires a lot of capital to be successful, especially since we were the very first to create this category with a meat and fruit bar. And with that comes all the competitors behind you. As we grew, the competition came in with a lot of money. We are very capital-intensive and privately owned on the reservation in South Dakota, trying to fulfill big goals and a big mission by returning buffalo to the lands, life, and economy of our people, bringing that economy back that was taken away from us.

As we grew, we just didn’t have the same financial backing as some of our competitors to compete in some of those big chains. Finance and capital was one of our main obstacles that we had to overcome. Throughout these last few years, it did get pretty competitive and we did struggle. But, we brought in the right partners to support us. We have great support and a great foundation and great people, a great product, and a great mission. We knew we had the recipe and the ingredients to make this successful. It was bringing the right partners in that wanted to fulfill the mission and keep us authentic, because we are the only Native American brand nationally recognized. It just took a lot of work being transparent. Partnerships move at the speed of trust. And recently we were able to close on our round of funding, as well as bringing in some other partners, such as Niman Ranch. They have been a great asset operationally, and they’re a values-based company as well as our equity partners that come in this year. So with that, we added to that recipe. Now we’re on that trajectory to grow and reclaim our space and be who we are.

cs: how do you define success for the business?

ds: I have to go back to the values of who we are, because success for us is not monetary—it’s really in taking care of the community and opening doors and providing opportunity. A successful day for us is being able to pass that knowledge down and educate somebody. With every relationship we’re building bridges to break down that isolation on the reservation. How we see success is being able to give back to our community and do what we want to do by restoring the buffalo, the land, and the economies of our people. We always look internally and say, “All right, how have we given back? What have we learned today and what’s the wisdom that we’re going to be able to pass on to everybody else?” As we grow, we just want to make sure to drive that impact back down to the communities.

cs: please share any advice you may have for indigenous entrepreneurs.

ds: Be resilient. You’re going to get a lot of no’s, more no’s than yes’s. So be resilient and be authentic, knowing you have a good idea and you want it to be successful and surround yourself with those people who are going to build you up. I always use this analogy: you have to face the storm. You’re going to go through a lot of hard times. The buffalo in a snowstorm, they face and walk towards the storm because instinctually they know that they’re going to come out of the storm. And that’s the advice I give everybody. Be resilient, face the storm. It’s going to be tough. But eventually, as you’re walking forward through that storm, you’re going to come out of it. So just build that support group around you, your herd, who you are. Build that herd around you.

e x CHANG e ON O UR Te RMS

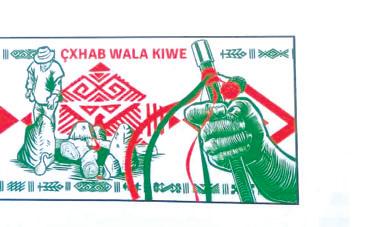

Cxhab Wala Kiwe Implements Own Currency

planning for the community currency pilot project.

out of 19 submissions, the winning design of the currency design contest for the pilot project was by hernando reyes artunduaga.

bia’ni madsa’ Juárez lópez (CS STAFF)

In an effort spanning several decades, the struggle for Indigenous autonomy continues in communities around the world. A focal point for gaining autonomy is economic freedom, as economic freedom drives growth, innovation, and mobility. Indigenous communities continue to explore the meaning of economic freedom in their own communities and look for alternatives to mainstream systems. One organization in Colombia that is working to enrich their community economically is Cxhab Wala Kiwe, which translates to “Great People’s Territory” in the Nasa Yuwe language. Cxhab Wala Kiweas is also known as Asociación de Cabildos Indígenas Norte del Cauca (ACIN). Made up of 22 Indigenous Nasa reservations and seven community projects with their respective representatives, ACIN is working to implement an alternative currency that facilitates the exchange of their members’ own products, goods, and services.

ACIN understands the importance of protecting domestic production because for a long time they have been surrounded by threats from paramilitary groups, transnational economic projects, and the federal government; it is from this context that the communities of northern Cauca formed ACIN. As Libia Sandoval Buritica (Nasa), coordinator of ACIN’s project, Complementary Currency for the Sovereignty of the Territory, explains, “The conflict with the government is our daily bread because our proposals are always focused on autonomy and independence, focused on freedom and the protection

of natural resources and the protection of the human resource of life. Unfortunately one has to say about our government— it is not said by me, everyone knows it—here the government is one of the most violent and corrupt in the world.”

The hope has been that congresses, councils, and internal assemblies can strengthen community mobilization to defend Indigenous territories with the needs of the community in mind. To protect and generate self-sufficiency, ACIN assists with economic solidarity projects concerning agricultural production, artisanal transformation, semi-industrial agriculture, livestock raising, and energy production. In accordance with ACIN’s mission to achieve political, economic, and territorial autonomy, the establishment of their own currency will help achieve territorial sovereignty. It will also advance the conversation about who has the right to land and its natural resources and normalize an economic system based on community transactions, which will help increase the levels of well being in the community.

The idea of alternative currency arose from the economic difficulties in the region, due in large part to the lack of cash and problems in the marketing of products. The communities identified that goods sold locally were mainly from outside companies that offered processed products such as soft drinks and chips, while foods that were produced locally, such as yogurts, were not sold equally due to competition from outside companies. This is why ACIN and communities took action. “Within our policies, we strive to generate food autonomy, economic autonomy, political autonomy, and territorial autonomy. So what the comrades did was join associations within the territory to produce their own food such as dairy products and juices. We have managed to displace some of the external products; however, this did not happen in all territories,” explains Sandoval.

Despite the progress made, not all territories have managed to fully regulate the purchase and sale of local products. For this reason, in 2018, community members called a congress to seek solutions to this problem. The Indigenous council of the Cxhab Wala Kiwe presented the proposal of local currency. The practical and pedagogical exercise was carried out, people saw how well it worked, and it was concluded that a currency should be made for the Nasa communities of northern Cauca.

The currency is defined by ACIN as a long-term project. Work on this issue began 12 years ago, and despite the long context of social conflicts in the area, they have persevered. In a recent call for proposal to 22 Indigenous communities, 19 responded with their own coin designs to a contest where the design was collectively chosen. Currently, and with the support of Cultural Survival’s Keepers of the Earth Fund, ACIN is conducting trainings on the alternative currency for colleagues who will take the experience to all ACIN territories. The pilot project was established in the Indigenous reservation in Munchique los Tigres. Sandoval says, “From there we began to expand to the other Indigenous reservations. We already have some who are in line wanting to handle the currency, so they are in that process. Being very ambitious, I hope that in five years the currency will be working throughout the Cxhab Wala Kiwe territory. That is my dream and I hope we can fulfill it.”

ACIN recognizes that having a currency is a necessary part of a mercantile system embedded in the global trading system. However, the entire process is always done following their Indigenous values, including the permission of the elders and with the involvement of communities. Respect for Mother Earth is the main value that governs their work, Sandoval says. “We never contemplate exploitation, because [land] is not ours . . . it is precisely because we are very much against multinational and government systems that sell our territories and grant concessions from our territories.”

ACIN dreams and works so that in the future, in addition to an alternative currency, they can set up their own bank to manage their resources. Cultural Survival is proud to collaborate with ACIN’s project, and we hope that the currency will serve as an exchange tool that will circulate exclusively within the resguardo (reservation). The use of this alternative currency will add to individual community projects, which bring attention and much needed funding for the community. The currency also provides protection for domestic production and reduces the entry of foreign products since large companies do not accept it. The protection of internal production and the reduction of external production is essential to economic autonomy.

Sandoval believes that Indigenous Peoples can achieve territorial and economic autonomy. “What I can tell you is that you simply dream and continue with the dynamic that makes you economically strong, but also identify what is weakening you and find out how to solve the issue. Because in walking, one only knows what is hurting us if we stop and examine, and maybe switch directions. One cannot continue doing the same thing and expect different results. You have to dare to do something different so that things change and work. You have to continue investigating. I invite you to analyze the issue of currencies, and if at any time you need some recommendations, we are here and open to sharing our experiences.”

currency use training in the community.

daisee Francour

Cultural Survival is honored to welcome Daisee Francour to our team as our new Director of Strategic Partnerships and Communications. She is Haudenosaunee and an enrolled member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin with relations to the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy in upstate New York and Canada. She was born and raised on the Oneida Indian Reservation in Wisconsin and comes from a matrilineal society and a long line of strong Indigenous women. “My mother and aunties taught me to always stand firm in my truth, to never compromise my values, and to always speak up in matters of injustice,” she says. Francour grew up immersed in her culture and is actively learning her Indigenous language alongside her family of six. She is a self-described artist, auntie, community member, Indigenous rights activist, and storyteller.

Francour holds a master’s degree in Public Policy and Administration from Adler University in Chicago and a bachelors in Sociology and Criminal Justice from the University of Wisconsin-Parkside. She comes to Cultural Survival with over a decade of experience working in philanthropy, at non-profit organizations, in grassroots organizing, and as a direct service provider in education, mental health, and corrections, where she has served Indigenous Peoples with disabilities/special needs, domestic violence victims, the homeless, and formerly incarcerated inmates.

“I grew up surrounded by my peers who were often criminalized for just being Indigenous. I saw them go in and out of the criminal justice system disporpotionately, and at a young age, I learned that our people were always on the frontlines of oppression and discrimination. I knew that the system was flawed and was designed to keep us on the lowest tier of civil society, so as a teen I decided I wanted to help transform the system so it would help our people, not destroy us,” Francour says about her motivation to get into her current line of work.

Francour’s experience in advocacy and movement-building work made her a radical woman in philanthropy.

As a former program officer at the Christensen Fund she managed the San Francisco Bay Area program, where she worked with Indigenous communities and organizations to support their efforts in stewarding and revitalizing biocultural diversity, traditional knowledge, Indigenous food systems, Indigenous languages, and sovereignty. Later, she transitioned into a consulting role as a strategist, resource mobilizer, organizational development consultant, and philanthropic advisor, supporting Indigenous organizations locally and globally.

“As someone who worked directly with Indigenous Peoples, providing them with the support and services needed to sustain their livelihoods, transitioning into philanthropy allowed me to continue that,” she says. “But I quickly learned that philanthropy is also flawed and inequitable in the amount of resources directed to Indigenous Peoples. Philanthropy has yet to fully grasp the importance Indigenous Peoples have in maintaining their environments and our expert knowledge in reversing climate change, conflict resolution, and maintaining balance in the natural world.”

Francour’s work empowers Tribes, Nations, and Indigenous-led institutions to build their capacity, leadership, and organizational infrastructure, and develop holistic strategies to support their resource generation and organizational sustainability. As an Indigenous fundraiser, philanthropic advisor, and donor educator, she builds capacity by transforming people’s understanding of Indigenous rights, Indigenous issues, biocultural diversity, climate and social justice, and other regenerative systems.

Francour says she is excited to join the Cultural Survival team: “Cultural Survival has been on my radar for many years and I have deeply admired the work it does to empower Indigenous communities in a variety of capacities via multiple layers of intentional and holistic support. Joining an organization with a 48-year legacy is exciting. To co-create a holistic vision and implement it alongside other incredible Indigenous women, men, and allies is a privilege. I feel that I have found my home outside of home, and I know my ancestors are behind me in this new journey. I am so honored to join Cultural Survival and their resilient team to bring my experience, love, and passion for Indigenous rights and decolonized/ Indigenized systems to this community. In ukwehuwehnéha, the Oneida language, we say, ‘ ʌkahake kalihwiyose,’ which means, good things are ahead.”

bazaar spotlight berber Art market

KEEPING OUR CULTURE ALIVE FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

Berber Art Market’s handwoven rugs are unique pieces of art. Based in the heart of Algeria in Ghardaïa, “the Pearl of the Oasis,” Berber Art Market operates out of the home city of the Amazigh Peoples, Beni M’Zab. The ancient city of Ghardaïa, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was founded almost 1,000 years ago in the M’Zab Valley in the Sahara Desert. Rug weaving has long been a major family craft in the region. Berber Art Market founder, Hocine Bazine, is proud of this connection to his heritage. “Our authentic Berber handwoven rugs are of high quality and are handmade with 100 percent sheep wool or pearl cotton with knowledge and skills passed down from our ancestors,” he says. These beautiful rugs are sought after for many home décor purposes— for living rooms, bedrooms, hallways, or entryways, and for hanging on walls.

In the age of factory-made goods, Bazine credits his grandmother for passing her weaving knowledge and love for the craft to him. “I have loved this art ever since I was a child. I learned rug weaving from my grandmother,” he says. “At a young age I had the pleasure of watching her create the most exquisite rugs, and go through the whole process of drying wool, arranging lines on the traditional hand loom, and producing a beautiful piece of art. I am grateful to those who encouraged me to save this heritage and fine art.” Berber rugs are woven for many purposes: for decoration, or for more utilitarian purposes such as bed coverings or sleeping mats. A local tradition is to furnish a bride’s room in handwoven rugs.

Bazine details the painstaking process of production. He explains that one of the most elaborate weaving techniques, carried out by specialized artisans, is the wrap, which is the essential part in a rug. In this technique, “the vertical yarn must be attached to the upper and bottom beam. The loom works to hold the threads vertically in place and allows the interweaving of the weft horizontally. The basic concept of weaving is to intersect the longitudinal threads, the warp, with the transverse threads, the weft (or woof). When the yarn is stretched and fastened to the loom, that would create a taut warp. It starts by working from the bottom to top. Hand loomed is a slow process that allows for the creation of durable weaves and highly detailed Berber patterns.”

Women generally work in all stages of drying and cleaning the wool, while men assist in weaving and applying designs and

above: hocine bazine at the cultural survival bazaar at the prudential center in boston, december 2018.

left: weaving on a vertical handloom.

below: traditional amazigh rug design.

drawings. The weavers use dyed scale of wool in various shades in white, red, brown, blue, grey, and black. In 2006, Bazine started working on some new techniques that allowed him to save time and effort while producing the same results. In 2012, he started his own business, Berber Art Market, as an independent weaver. “It was then,” he says, that “I realized that I had to keep this noble art alive for the next generations. Many Berber families gain their daily bread from manufacturing rugs and carpets. I strive to help families rise out of poverty by buying their wool and employing them as weavers. Keeping my Berber culture and its legacy alive motivates me to work harder and harder.”

Since founding Berber Art Market, Bazine has also begun traveling to exhibit his art, participating in different exhibitions such as the U.S. Embassy Bazaar and at the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He has also participated in the Cultural Survival Bazaars several times since 2018. In Bazine’s home region of Ghardaïa there isn’t much tourism, so access to market is a significant obstacle for artisans. Many artisans also lack tools for development and access to transportation. Yet, Bazine remains undaunted: “I have a great desire to carry out my mission. For each obstacle, I try to find a solution. My goal and passion is helping lots of families out of poverty by offering them a source to earn a living. This, in addition to keeping our culture and legacy alive, is a motivation to work more and more. All those things grew through me and encouraged me to continue this heritage and save this noble art.”

missed the virtual winter cultural survival bazaar series? watch it and support indigenous artists at bazaar.cs.org.

Five easy ways to support Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival this giving season

1

Make an online donation to Cultural Survival and save a tree! Become a monthly sustainer. set it and forget it. Help us spend more resources on programs with Indigenous peoples.

2

Give a gift subscription of the Cultural Survival Quarterly to someone you love. donate online or call the number below.

3

Invest in future generations. Include cultural survival in your estate plans and leave an important legacy for future generations. Visit www.cs.org/ plannedgiving

4

Give appreciated stock! save on capital gains taxes by donating your appreciated stock and other securities today.

5

be social. like us on facebook (facebook.com/ culturalsurvival) and follow us on twitter (@CSORG) and Instagram (@culturalsurvival). tell three friends about cultural survival and invite them to become members.