20 minute read

Fitness fanatics happily return to in-person workouts

Though smaller fitness studios have been able to reopen, large facilities like Memorial Gymnasium remain closed.

Advertisement

Working it out

Charlottesville goes back to the gym

By Emily Hamilton

Heavy breathing, lots of sweating, and plenty of people nearby— gyms and workout studios seem like a perfect place for COVID transmission. Though some industries have been slow to recover during Virginia’s phased reopening, gyms have seen customers eager to return. Workout spots around town have adopted stringent safety protocols—and benefited from customers who are desperate to get out of the house and move around.

After at least three months of closure, gyms and fitness facilities in Virginia were given the green light to reopen when Virginia entered Phase 2 on June 12.

Michael Towne, owner of Solidarity CrossFit, adapted to COVID by installing an elaborate new fan system to redirect the airflow in the gym. “We have redesigned our gym airflow extensively in response to the growing science related to airborne transmission,” Towne says. “While we can service less clients than before, we are actually working more and upping our offerings, which is I think a trend for many businesses due to the nature of running a facility during a pandemic.”

Purvelo, the popular Charlottesville-based cycling studio, reopened a few weeks ago. Ian Dillard, a seasoned instructor at Purvelo, says the early days of the shutdown were hard for the studio. “Like all small businesses, COVID has definitely had a huge impact on Purvelo,” he says. “Financially, we have definitely taken a hit.”

But in recent weeks, the studio has enjoyed full classes, and even had potential pedalers on their waitlist. “We are seeing demand for classes and we have been able to meet that demand while also using safe practices,” Dillard says.

Erica Perkins, executive director of intramural-recreational sports at UVA, oversees operations of the university’s four recreation and fitness centers. UVA closed its facilities on March 18. The Aquatic & Fitness Center reopened on August 3, and the North Grounds pool reopened by reservation only on August 10.

Perkins says she has received an abundance of positive feedback from patrons who have decided to return. “People are exercising and have been both compliant with policies and appreciative of our services and safety procedures,” she says. “We have been very impressed with the positive response to our operations.”

Like the smaller studios, Perkins says the UVA gyms suffered financially. “The Intramural-Recreational Sports Department has not been able to host or offer the range of activities and events that typically generate revenue and has suffered membership losses while we were closed,” she explains. Memorial Gymnasium, where basketballs and volleyballs normally bounce incessantly, remains closed and empty.

While the revenue lost from months of in-person classes was substantial, many gyms stayed afloat by offering virtual fitness classes to their members. “We responded early at the start of the pandemic and pivoted to virtual classes and run and strength coaching services to maintain many of our members,” says Ann Dunn, owner and founder of Formula Complete Fitness. Now some customers are coming back in person, too.

The gym industry finds itself at the center of a paradox: Months of quarantine and isolation have left people antsy and eager to get out and exercise, but going to the gym also means risking exposure to COVID. It seems, though, that this is a risk that many Charlottesville gym-goers are willing to take.

You’re focused on convenience. We’re focused on you.

You’ll find everything you need at our new Stonefield Financial Center in Charlottesville.

C&F Bank C&F Wealth Management C&F Mortgage Corporation

Lobby & Drive-Thru Hours M-Th 9 a.m. - 5 p.m. l F 9 a.m. - 6 p.m.

Stop by 3920 Lenox Avenue to meet with Kim Garrison, our VP, Retail Team Leader, or give her a call 434.284.4422.

Elijah. Julia. Sam. I took in every name, and let each resonate within me, as I quietly examined the granite slabs. I saw the name of my brother, then I saw it several more times. If he had been born just over 150 years ago, he could have been enslaved at the

University of Virginia, alongside the rest of our family.

But what struck me even more were the unnamed. Of the 4,000 deep gashes inscribed into the memorial walls—each representing a person enslaved at the university—only 578 have names resting above them. Because they were viewed as property, and treated as such, the identities of more than 3,000 men, women, and children remain lost to history, and may never be discovered.

With its compelling symbolism and innovative design, the

Memorial to Enslaved Laborers urges its visitors to confront these cruel realities of slavery, and honor the countless contributions enslaved people made to UVA, left unacknowledged for nearly two centuries. It is a site for learning, mourning, and remembering, as the university works to heal from its violent past.

As recent protests against systemic racism held at the memorial show, it also serves as a call for change. The painful effects of slavery can still be felt and seen around UVA today, and the school has a long way to go to achieve racial equity. But for many, paying respect to the Black people who built the university is the first step in the right direction, and offers a glimpse of a better future.

STEPHEN BARLING

LONG TIME COMING

In 1619, the White Lion landed in Point Comfort, Virginia. The “20 and odd” Angolans aboard the ship were sold to Governor Sir George Yeardley, and brought to Jamestown— becoming the first enslaved Africans in England’s colonies in the Americas.

Nearly 400 years later, in 2007, the Virginia General Assembly issued an apology for the state’s role in the institution of slavery. UVA’s Board of Visitors followed suit two months later, expressing “profound regret” for By Brielle Entzminger the university’s use of enslaved people. Earlier that year, the board also voted to place a small gray stone marker in the ground near the Rotunda, honoring the “several hundred women and men, both free and enslaved, whose labor between 1817 and 1826 helped to realize Thomas Jefferson’s design for the University of Virginia.”

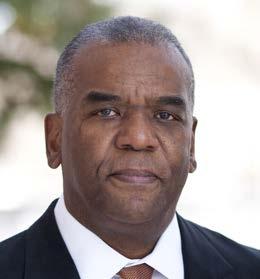

“Most people step over it all of the time,” says Marcus Martin, MD, former vice president and chief officer for diversity and equity at UVA. The low stone “falls short in that it’s not very visible, and only talks about the period of 1817 to 1826. …Slavery didn’t end until 1865, and there were more than several hundred free and enslaved men and women [who] helped erect the university and maintain it.”

“The university, at that point, didn’t have the tradition of telling the full story about its history. Everything was focused on Jefferson,” says UVA history professor and associate dean Kirt von Daacke. “There was sort of a sense that Jefferson’s hand was in everything—he built it, he designed it. That was a vague myth.”

In 2010, two students—one an intern for University and Community Action for Racial Equity, the other a co-chair of the Student Council Diversity Initiatives Committee— took the controversy surrounding the marker as a chance to raise greater awareness about slavery at UVA, forming a group called Memorial to Enslaved Laborers.

The group organized community discussions on the creation of a memorial, among other initiatives. And the following year, it held a design competition.

“There were some neat concepts, but they were not of the quality to withstand the environment and test of time, [and] to be approved and erected on Grounds,” says Martin.

Accompanied by student leaders, Martin met with thenpresident Teresa Sullivan’s cabinet in 2013, proposing the university create a commission entirely dedicated to studying the university’s history of slavery, and recommending ways to commemorate the contributions of enslaved people— including a memorial.

The President’s Commission on Slavery and the University was soon born, with Martin and von Daacke as

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1 5 co-chairs, and a range of professors, faculty, and community historians as members.

According to von Daacke, it was not easy getting everyone on the Board of Visitors to agree to build the memorial “sooner rather than later.”

“When you start with projects like this, running counter to how you’ve done things before, there’s often a sort of fear-based perspective about it. That if we do this, it will bring protests. ...That it’s talking about an unpleasant reality of the university’s past, and will be bad for the university, ” he explains.

“Our job [as the PCSU] was to convince everybody that no that’s not true. ...Embracing difficult history is beneficial to us in a multitude of ways,” he says. “That takes some time. You have to do the research and public talks, where everyone gets used to hearing these stories, and you have to talk to people one-on-one. [But] protests aren’t going to come unless you do nothing.”

In 2016, after years of lobbying, the BOV finally commissioned the memorial, and put together a design team: architecture firm Höweler + Yoon; alumna and architectural historian Dr. Mabel O. Wilson; landscape architect and professor Gregg Bleam; polymedia Nigerian-American artist Eto Otitigbe, and community facilitator Dr. Frank Dukes, co-founder of University and Community Action for Racial Equity and past director of the Institute for Environmental Negotiation at the UVA School of Architecture.

The design team immediately sought input from the community, sending out surveys and hosting public forums for students, staff, faculty, alumni, local residents, and descendants of the enslaved both inside and outside of Charlottesville, with the support of the PCSU.

In 2017, the BOV approved a final design and location for the memorial, and allocated funding toward its $7 million price tag the next year, alongside private donations.

After about a year of construction, the project was completed this April. Though its dedication ceremony had to be rescheduled for next April—during Black Alumni Weekend—due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the memorial is now open, “demanding you pay attention and interact with it,” says von Daacke.

The memorial “is really a reflection of the community in Charlottesville,” says Otitigbe, who is based in Brooklyn, New York. “[We] had a lot of interesting conversations with different community members and descendants…I am really thankful they all welcomed me and allowed me to do this, because I was essentially working with, in some way, the remains of their ancestors.”

STONE AND SYMBOLS

The memorial’s stone was quarried nearby—it’s a variety of granite called Virginia Mist. The name fits: The memorial’s designers hope this stone can provide a physical representation of a murky and poorly documented past.

“One of the first things we heard [from the community] was you can’t build a memorial that is meant to humanize the enslaved without picturing humanity in some way,” says von Daacke “This was sometimes interpreted as a call for a figurative sculpture of an enslaved person,” like Isabella Gibbons, who was enslaved at UVA and became an educator in Charlottesville after emancipation, he explains.

DAN ADDISON / UVA COMMUNICATIONS Kirt von Daacke

“But of course at UVA, we can’t do that. We have no images of enslaved people at UVA. We have post-emancipation photos, [which are] probably not good images to use to capture what life was like in slavery,” he adds. “Or there are pictures of people who continued to work for the university during Jim Crow, and were treated by white Charlottesville and UVA as the faithful slave. Their picture and story were told by [whites], and is not reflective of who these people were.”

Instead, architectural historian Wilson proposed a more abstract, circular structure for the memorial, symbolizing the broken chains of slavery. It’s also a nod to the ring shout, a dance rooted in West African traditions celebrating spiritual liberation practiced by enslaved people, during which they clapped, prayed aloud, sang hymns, and shuffled their feet in a counterclockwise direction. The ring is 80 feet in diameter—the same as the Rotunda.

“It’s nice that [the memorial is] visible from town and not within the enclosure of the university, on the Lawn or on Grounds, where these people

were forced to work,” says Jalane Schmidt, a UVA religious studies professor and community activist. “They had complete lives. They did not define themselves solely as laborers. ...They were members of a community.” The design team says the horizontal slashes that are spread across the interior wall of the memorial’s larger ring JOHN ROBINSON are reminiscent of scars from brutal UVA student Sarandon Elliott believes the memorial must be accompanied by structural reforms. whippings that once covered the enslaved peoples’ bodies. After years of examining historical reA second, smaller ring inside the larger circle contains a cords, researchers were able to find the names of 578 people shallow water fixture, symbolizing the rivers used as pathways enslaved at the university to add to the wall above the memoto freedom, as well as African libation rituals, baptismal ry marks, along with 311 people known by their occupation ceremonies, and the Middle Passage. Once the fixture is or kinship relation. However, the rest of the marks remain turned on, water will flow over a historical timeline etched nameless, laying bare the violent dehumanization of slavery. into the ring detailing the everyday experiences of enslaved

This wall “extends the narrative about who this African people at UVA, beginning with the first enslaved Africans American community is…[and] allows us to have distinct arriving in Virginia in 1619 and concluding with Gibbons’ conversations about what their service looked like,” says death in 1889. Andrea Douglas, executive director of the Jefferson School Stepping stones adjacent to the memorial point to the African American Heritage Center, and a member of the North Star, which led enslaved people to freedom. And the PCSU. “It really gives a better agency to people who were at brick walkway visitors use to enter the memorial will align some point largely dismissed.” with sunset on March 3, or Liberation and Freedom Day,

Every inch of the memorial was designed purposefully, when Union troops emancipated enslaved people in Charlotand every detail is symbolic. tesville at the close of the Civil War.

The eyes of Isabella Gibbons are inscribed on the outside The smaller ring encircles a fresh cut lawn, a space for of the wall. Otitigbe used a post-Emancipation photo of her gatherings, celebrations, performances, classes, and protests to lightly carve her eyes into the rough-hewn granite, so they centered around topics of racial justice. are only clearly discernible in early morning or late day. An excerpt of one of Gibbon’s writings from 1867 appears

“Her eyes are looking out to the community, and that can at end of the timeline: “Can we forget the crack of the whip, represent many things,” says Dukes. “To me, it’s asking ‘What cowhide, whipping-post, the auction-block, the hand-cuffs, are you doing? We’re here—what are you doing about it?’” the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? … No, we have not, or ever will.”

SUPPLIED POHTO Jalane Schmidt

IN VIEW

Douglas arrived at UVA as a graduate student in the ’90s. Confederate flags flapped from fraternity house windows, and students regularly popped up at parties wearing blackface. (Those things still happen, but with a little less frequency.) “White supremacy was very much inculcated into the culture of the

school,” she says. “Going to a university with that much blatant anti-Black racism, to have this [memorial] as prominent as it is [and] know there is a movement towards a kind of respect for the community the university sits in...It feels much different from when I got here.”

For activist Don Gathers, seeing the names—or lack of names—on the memorial for the first time was “incredibly powerful,” bringing him to tears, he says.

“To stand there and take it all in—it speaks volumes to you. You realize the struggle and sacrifice that those individuals made, and were forced to make, to bring us to the point we are now.”

Though the memorial is effective, Gathers believes the location could have been better chosen.

“Where it is, it still has the semblance of...the Rotunda and Jefferson himself looking down upon the enslaved,” he says.

“Community members told us that they don’t go on Grounds,” says Dukes. “We don’t feel welcome. So if you build it on the Grounds...we’re not going to come. It’s not going to be for us.”

Third-year Black student activist Sarandon Elliott believes the location of the memorial makes it much more visible, especially to students.

“When people walk towards UVA, they’re going to have to see that. And I also like that it’s near the Corner, a really busy area. People walking past it can stop and reflect upon it,” says Elliott, president of the school’s Young Democratic Socialists of America.

It remains to be seen if the memorial’s current location— technically off Grounds but still very much amidst the UVA bubble, tucked between the hospital and the Rotunda, just across the street from the student-swarmed Corner, will attract a lot of Charlottesville residents.

Though it’s just about impossible to identify every enslaved person, von Daacke and other researchers continue to search for names, occupations, and kinships to engrave on the monument’s inner wall. (A handful have already been found since it was completed, he says.)

Last year, UVA also began discovering the names of enslaved people through its new descendant outreach project, spearheaded by renowned genealogist Shelley Murphy, which will continue for at least the next two years.

The descendants have formed a leadership group, but are still getting themselves organized, according to UVA employee and descendant DeTeasa Gathers. They plan to conduct educational tours and talks at the memorial, when the pandemic finally comes to an end.

“We consider this very vital, because the history books in Virginia are not inclusive and not very detailed [on] the quandary of slavery,” says Cauline Yates, who is also a descendant. “[Students] are our up-and-coming leaders of the future. We’re trying to make sure that they understand what even happened in their very own backyard.”

“This is not completely about us. This is more about telling the unvarnished truth about what happened going forward,” says DeTeasa Gathers. “We see this memorial as people who were enslaved...but it did last for generations past. It’s important to not forget the generations behind it who have been affected.”

STRUCTURAL CHANGE

Shortly after the murder of George Floyd, dozens of UVA Health employees gathered at the memorial, kneeling for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin dug his knee into Floyd’s neck.

In addition to raising awareness about police violence against Black people, the group called attention to systemic inequality and racism in the health care system—bringing a crucial purpose of the memorial to fruition.

Now that the memorial is finished, the university needs to answer its call to action, and implement real changes, says Schmidt.

The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers “is the sculptural, African American version of institutions’ spoken indigenous

STEPHEN BARLING Inscribed on the memorial’s granite rings is a timeline of slavery at the university, as well as a series of dashes and names representing the enslaved people who worked there.

land acknowledgments, both now made with fanfare and solemnity: It’s a nice gesture,” she says. “But absent concrete material actions of repair, it remains just a gesture.”

Martin echoes Schmidt’s calls for sweeping structural change, pointing to the detailed list of recommendations the PCSU made in its final report to Teresa Sullivan in 2018.

For Martin, one of the most crucial issues facing UVA is its small population of Black students. While the state of Virginia is nearly 20 percent Black, only about 7 percent—a little over 1,000—of the university’s undergraduate students are Black.

UVA doesn’t just need to admit more Black students, but figure out how to attract and keep them here, explains Martin. He says the university offers admission to around 1,000 Black students each year, but only 35 percent of them accept.

A solution, he says, would be to offer more scholarships through the Ridley Scholarship Fund, minimizing the student debt for a demographic that statistically already has less wealth. The university could also explore ways to create a need-based scholarship fund for descendants of its enslaved laborers through the fund.

Martin also calls for the creation of more fellowships related to Black studies, so the school can attract more Black faculty—4 percent of the faculty of the state’s flagship university is Black.

Schmidt is all for more scholarships, but she believes UVA needs to include reparations in its admissions practices, like Georgetown University, which, since 2016, has given preferred admissions, or “legacy” status, to the descendants of those enslaved there.

UVA should not just aim to get more Black students, but also make them feel included and valued once they are on Grounds, says Elliott. This includes following up on the range of recommendations issued by the university’s Racial Equity Task Force last month, and removing racist symbols and names—from Alderman Library to the George Rogers Clark statue.

“If we are not actively fighting racial and economic inequity, we are not properly honoring enslaved peoples,” she adds.

After spending an hour or so at the memorial, I left feeling pained. Black people at UVA, in Charlottesville, and across the country have endured so much violence and oppression. The memorial is here, but the violence has yet to cease.

But I also left with a sense of hope. Now more than ever, radical student leaders and activists of color like Elliott are holding the university accountable for its racism—without the initial push from students, it’s likely the memorial wouldn’t exist today. Through their efforts, and the efforts of the next generation, and the next, UVA may someday atone for its troubled past.

CULTURE

Laura Wooten Michael Brunelle Sahara Clemons

The Bonnet Maker

Tobiah Mundt

Cate West Zahl

Heather Owens

THROUGH 9/25

Cassie Guy

LITTLE LOOKS

The biggest little show of the year returns when “Teeny Tiny Trifecta 3” begins this week. The juried group exhibition is a collection of three pieces, all measuring nine inches or smaller, from over 100 area artists who work in a variety of styles. The show also celebrates Second Street Gallery’s 47th season, and its reopening to the public. Thursday and Friday viewings are offered as private access ticketed entries, before free appointments begin on Saturday. Public voting for the Audience Choice Award will be available online and in the gallery. Second Street Gallery, 115 Second St., SE. secondstreetgallery.org.

Sarah Boyts Yoder

MONDAY 9/7

AMONG THE VINES

The last weeks of summer are always bittersweet, marked by the start of school, cooling temps, and a surplus of garden veggies. Chef Ian Rynecki helps make sense of the season’s bounty at Shenandoah September Sizzles , a celebration that begins with a garden tour to harvest fresh produce, followed by a grilling/smoking/cooking demo, and topped off with dinner and a sunset. Limited enrollment. Gloves and masks will be provided. $125, 6pm. Pippin Hill Farm & Vineyards, 5022 Plank Rd., North Garden. 202-8063.