1250 Bellflower Blvd., LA4-203 Long Beach, CA, 90804

Phone (562) 985-8000

El Nicklin

Sam Farfán

ON THE COVER

Graphic by MARY CATIPAY / Long Beach Current

As Long Beach State celebrates its 75th anniversary, so does the Long Beach Current. The cover features publication staff and faculty from the 1950s to the present.

Acsah Lemma

Linsey Towles

Managing Editor Editor in Chief Community Engagement Editor

Editorial Office Director of Business Operations

Kristina Agresta

Multimedia Managing Editor business@gobeach.media managing@lbcurrent.com eic@lbcurrent.com community@lbcurrent.com multimedia@lbcurrent.com

editors

Juan Calvillo News Editor news@lbcurrent.com

Julia Goldman Arts & Life Editor arts@lbcurrent.com

Joannah Clemente Opinions Editor opinions@lbcurrent.com

Davis Ramage Sports Editor sports@lbcurrent.com

Jaylyn Preslicka Solutions Editor solutions@lbcurrent.com

Mary Catipay Design Editor design@lbcurrent.com

Khoury Williams Copy Editor

Photo Editor

Samuel Chacko

Stephanie Morales Social Media Editor

Dante Estrada Video Editor

Aidan Swanepoel Podcast Editor

copy@lbcurrent.com photo@lbcurrent.com socials@lbcurrent.com video@lbcurrent.com podcast@lbcurrent.com

Mnewspaper’s founding, looking back at major events throughout the decades.

News Assistants Ethan Cohen

Annette Quijada

Mayra Salazar

Grace Lawson

Diego Renteria

Opinions Assistants Lizbeth Cortes-Gutierrez

Sports Assistants

Romi Mathews

Christine Nader

Matthew Coleman

Alyssa De La Cruz

Matthew Gomez

Jack Haslett

Soleil Cardenas Design Assistants

Luis Castilla

Timothy Hessen Copy Assistants

Photo Assistants

Social Media Assistants

Bella Garcia

Lauren Benson

Justin Enriquez

Devin Malast

Mark Siquig

Matthew Gregory

Andrew Miller

Video Assistants Eduardo Contreras Jr.

Kimberly Perez

Gianna Echeverria Podcast Assistants

Alexandra Gryciuk

y name is Acsah Lemma and I am the Editor-in-Chief of the Long Beach Current. The print issue you hold in your hand is the second print issue of the 2024-25 academic year and the second issue for the publication being under a new name.

On Sept. 28, 1949, Los Angeles-Orange County State College began its first day of classes. Less than a month later, on Nov. 11, the Daily Forty-Niner released its first issue. Today, 75 years later, both are still active, both under a different name.

The year 2024 marks the 75th anniversary of Long Beach State and the Long Beach Current, the university’s paper of record and long-running archive. This month’s print issue commemorates both the university and the

In this issue, you will find stories and research written and put together by the Long Beach Current staff, who stand on the shoulders of the very first team of writers responsible for the founding of the Daily Forty-Niner 75 years ago.

Readers can enjoy stories cataloging the best athletes and Olympians in LBSU history, a look back into Long Beach during 1949 and a profile on one the oldest buildings on campus.

We hope you enjoy this historically rich issue of the Long Beach Current. We here at the Current have upheld the legacy and dedication of our student staff for 75 years and we hope to be here recording our history for 75 more.

ACSAH LEMMA Editor-in-Chief

Land acknowLedgment Business

Andrea Contreras Advertising Manager advertising@gobeach.media

Jennix Bien Creative Director

Web & Technology Director

Leila Nuñez

web@gobeach.media creative@gobeach.media

Nicollette Combre PR & Marketing Manager

Distribution Manager

assistants advisers

beach.pr@gobeach.media

Joseph Vargas

Madison Yang distribution@gobeach.media

Gary Metzker Design Adviser

Barbara Kinglsey-Wilson Content Adviser

Jennifer Newton Advertising & Business Adviser

Here at the Long Beach Current we acknowledge that the school we report on is located on the sacred site of Puvungna, “the gathering place”. We are on the land of the Tongva/Gabrieleño and the Acjachemen/Juaneño Nations who have lived and continue to live here.

We also acknowledge the Gabrieleño/Tongva (pronounced: GABRIEL-EN-YO/TONG – VAH) and Acjachamen/Juaneño (pronounced: AH-HACH-AH-MEN/JUAN-EN-YO) as the traditional custodians of the Los Angeles region along with the Chumash (pronounced: CHOO-MOSH) to the north and west, and the Tataviam (pronounced: TAH-TAH-VEE-YUM) and Cahuilla (pronounced: KAH-WEE-YAH) Nations to the east.

We respect and value the many ways the Tongva/Acjachemen cultural heritage and beliefs continue to have significance to the living people and remind us about the sacred and spiritual relationship that has always existed here at what we now call California State University Long Beach.

editoriaLs: All opinions expressed in the columns, letters and cartoons in the issue are those of the writers or artists. The opinons of the Long Beach Current are expressed only in unsigned editorials and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the journalism department or the views of all staff members. All such editorials are written by the editorial board of the Long Beach Current.

Tuesday, September 17, 2024

Letter PoLicy: All letters and emails must bear the phone number of the writer and must be no more than 300 words. The Long Beach Current reserves the right to edit letters for publication in regard to space.

BY ETHAN COHEN News Assistant

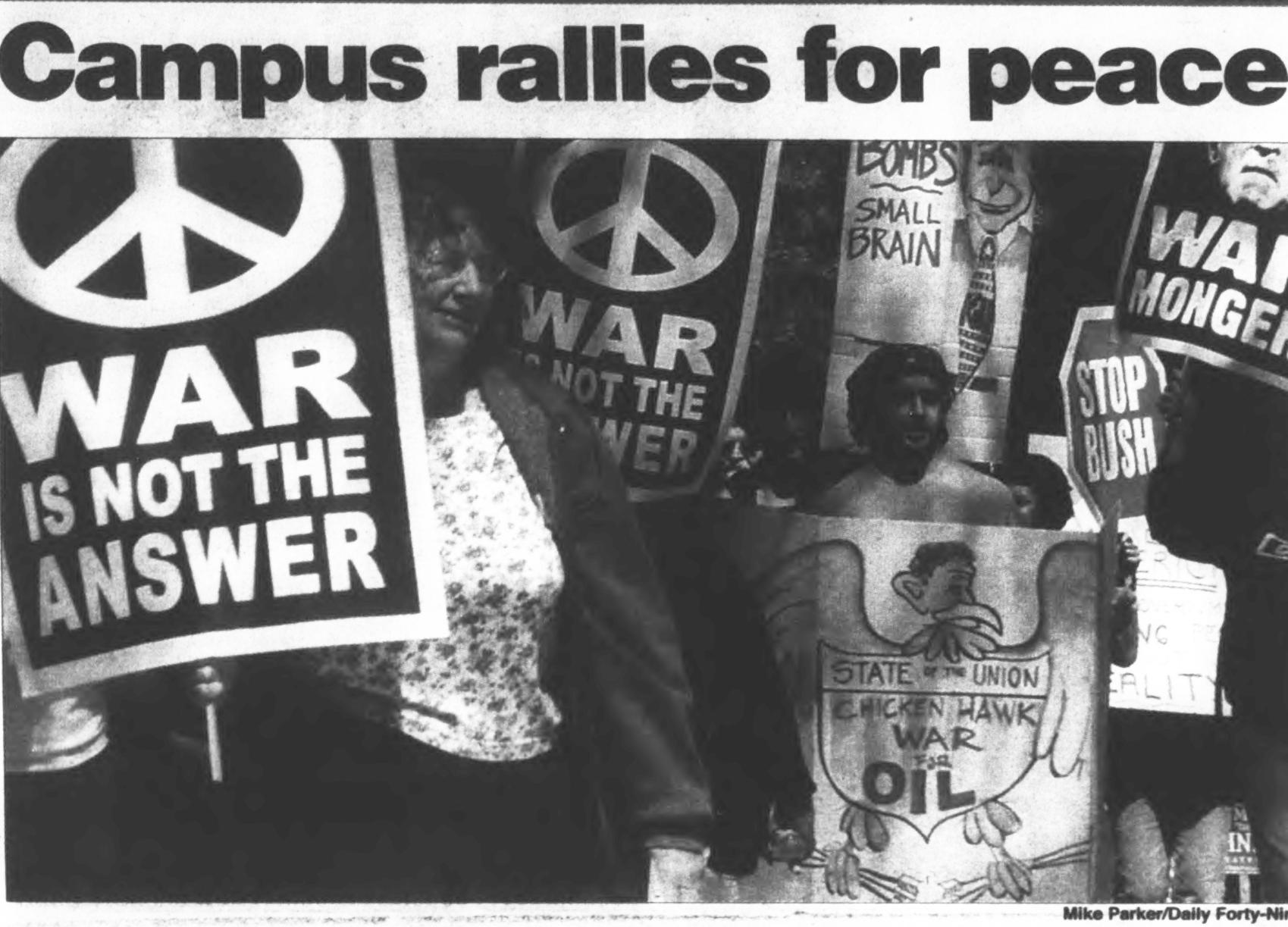

Student activism has been a defining feature of Long Beach State since its founding in 1949. Over the past 75 years, students and faculty have used the campus as a stage for social and political change, reflecting broader national movements in American eras from the 20th to 21st centuries.

For every instance of social upheaval, the Long Beach Current has been present to document and cover the ever-changing history of the campus.

From the early civil rights marches and Vietnam War protests to movements addressing environmental issues, racial justice, tuition hikes and ongoing conflicts, students have consistently played a pivotal role in shaping the campus community and the broader society.

These protests and social justice movements are a testament to the university’s role as a place to foster dialogue, engage in activism and shape the future of the community and beyond.

In the 1960s, CSULB saw its first major events of social action and protest, largely inspired by the national civil rights and anti-war movements.

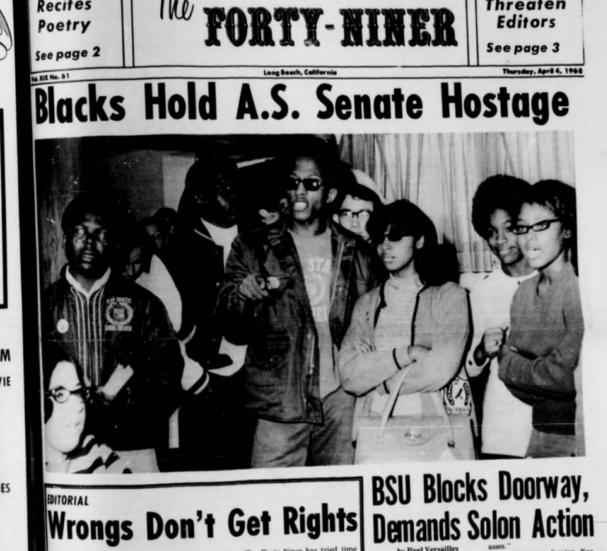

On April 4, 1968, the university’s Black Student Union protested the lack of Black representation in the student government, eventually occupying the Associated Students Inc. council chambers.

According to the Long Beach Cur-

rent, formerly the Daily Forty-Niner’s archives, the action by the Black Student Union resulted in two resolutions passed by the student government to address Black representation on campus issues.

As the Vietnam War intensified and the draft reached close to home, anti-war demonstrations sprang up across the country. CSULB was not spared with an explosion of student activism and sitins protesting for the U.S. to cease its involvement in Vietnam.

From 1967 until the early 1970s, students and faculty were involved in a myriad of protests which saw confrontations with military recruiters and the shutting down of campus.

Anti-war protests also sprang up in 2003 as the U.S. escalated conflict against Iraq during the war on terror.

Protest against tuition increases and budget cuts

Throughout the decades, CSULB students have repeatedly mobilized against the rising tuition and budget cuts the college has faced.

Students and faculty argued continuous tuition hikes threatened the accessibility to higher education.

For as long as the college has served the greater Long Beach community, the issue of tuition and budget has been at the forefront of student activism culminating in walkouts, marches and sit-ins with students demanding increased state funding and financial aid.

One notable example was last year’s campus protest against tuition increases. Students marched across campus to raise awareness and highlight their frustration with the cost of education.

According to the archives, there has been at least one demonstration against the rise in tuition for nearly every decade since the 1960s. However, the most notable period in which students protested was from the early 1990s to the 2010s.

Racial tensions and justice

From the Black Student Union’s protest of the student government in the 1960s to the sweeping Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, racial equality and social justice have long been a focal point of activism at CSULB.

Following the 1992 Rodney King verdict, where four Los Angeles Police Department officers accused of beating King were acquitted, students took to the campus in outrage.

“It was an obvious miscarriage of justice,” Maulana Karenga, chair of the Black Studies Department in the original 1992 Daily Forty-Niner article, said. “It reflects the race and class dimensions of justice where some races are favored more than others.”

At the time when the Current interviewed students, many said the community would reap the repercussions of the verdict.

The CSULB campus was eventually closed and classes were canceled due to the riots near and around the campus.

More recently, the student and faculty community united together during the BLM movement after the death of George Floyd, raising issues of police brutality and racial injustice that continue to this day.

The Long Beach Current, formerly the Daily Forty-Niner, exclusively covered protests on and around CSULB for racial justice, including the arrest of a student.

Students and faculty continue to take to the streets, advocating for causes, movements and beliefs. Each demonstration, in its own way, has contributed to shaping the social and political change on our campus.

From the early civil rights marches and Vietnam War protests to movements addressing environmental issues, racial justice, tuition hikes and ongoing conflicts, students have consistently played a pivotal role in shaping the campus community and the broader society. ”

BY ANNETTE QUIJADA News Assistant

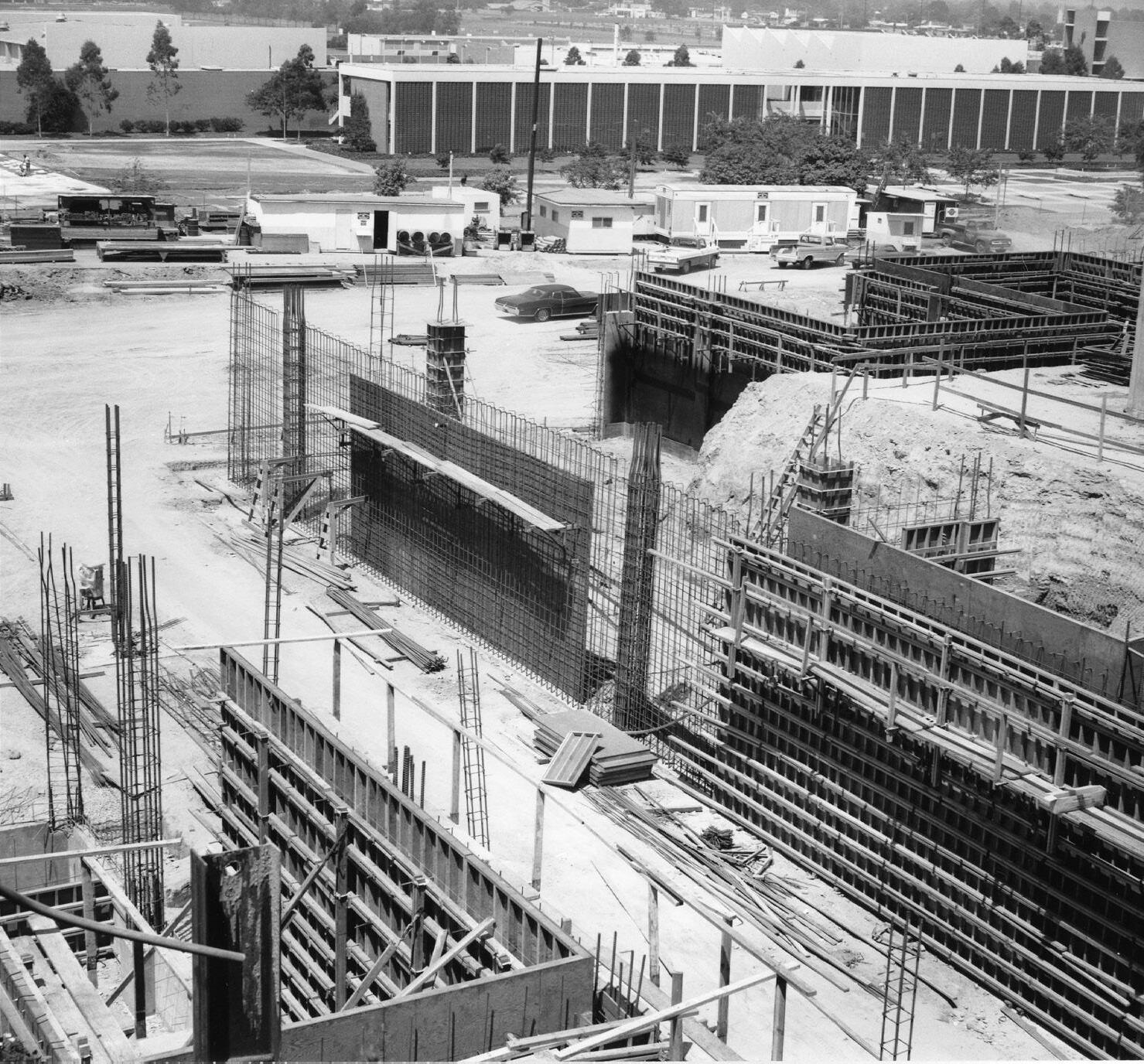

he University Student Union has been a part of Long Beach State since January 1957.

Long Beach Soroptimist, a volunteer service organization, raised the money to build and design the university’s first student union. Named the Soroptimist House, the fully furnished 1450 sq. ranchstyle house included a meeting room, kitchen and garden and was donated to CSULB’s Associated Students, Inc after construction.

“The Soroptimist House will be used by service organizations, special interest and religious clubs. It is not for the Greeks, since they will have their own houses. Until they do, however, they will be able to use the house for exchanges and other functions excluding regular meetings,” Loris Swanson, previous dean of activities, said in an interview from the Daily Forty-Niner archives.

In the 1960s, students realized the house would no longer be enough to support the university’s growing population. In 1965, students voted to raise fees and build the USU. Construction began the following year.

Architect Edward A. Killingsworth designed the USU in addition to other areas of the CSULB campus.

The USU officially opened on Sept. 19, 1972. The new building was 148,000 sq. ft. and filled with amenities such as billiards, bowling, music, food vendors and other student services.

Over the following years, USU and student population needs increased.

• 1990s - The USU Improvement Project “Building Better - Brick-byBrick.” Students voted for an increase in student fees, which added the third floor, the west wing and the escalators.

• 2000s - A campaign to build the Student Recreation and Wellness Center. Students voted and the SRWC opened in the fall of 2010.

• 2010s - The USU Board of Trustees and ASI assessed students’ needs to renovate and expand the USU for more

lounging, study and dining spaces. Students voted for the referendum; it did not pass.

• 2016 - ASI Beach Pantry opened at the USU to serve students who experience food insecurity.

• 2017-2018 - USU Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing Project.

• 2020s - The USU Board of Trustees approved a proposal to work with engineers to look at renovation and expansion for the USU.

Currently, the USU has three floors. The first floor houses the ASU Beach Pantry, 22 West Media Radio, Basic Needs, lounging and study spaces.

The second floor is made up of the food court along with student services including the Dean of Students Office, Student Life and Development Office, Elektric Hair Salon and more.

On the third floor, students can find the ASI government office, all-gender restrooms and meeting rooms.

During the 2022 - 2023 school year, ASI did an outreach campaign called The Future U Project, to see if students were interested in expanding and renovating the USU. ASI did a feasibility study to assess the building and the land.

ASI Communications Coordinator, Shannon Couey, said the biggest challenge the USU faces is the old infrastructure.

“The facility doesn’t accommodate the increased student population anymore. One of the biggest challenges is the building is so old and with that comes challenges in plumbing and ventilation. Because the building is so old it’s hard to retroactively bring an old building into the 21st century and accommodate the students of this time,” Couey said.

She said they are currently in the design and blueprint phase but are expected to break ground in the fall of next year.

“We are looking to improve a lot of issues with this new building. Students deserve a building that operates well in the 21st century,” Couey said.

The timeline for the construction of the USU is set to be completed in August 2028.

Shannon Couey ASI Communications Coordinator ”

The facility doesn’t accommodate the increased student population anymore. One of the biggest challenges is the building is so old and with that comes challenges in plumbing and ventilation.

BY JUAN CALVILLO News Editor

Over the last seven decades, many college departments at Long Beach State have changed and evolved dramatically. The 2024 fall semester has already seen such a change, with the Film and Electronic Arts Department becoming the Department of Cinematic Arts.

Departments like the French, Italian, German, Russian and Classics departments underwent a simple name change, becoming the Romance, German, Russian Languages and Literature department.

However, some programs such as Home Economics changed several times before eventually disappearing.

According to the 1950 yearbook from the CSULB Special Collections and University Archives Amy Marie Smith graduated with a degree in her chosen major, Home Economics. At the time, CSULB was called Long Beach State College. Smith was one of 31 seniors who graduated that year.

By 1954, coursework in Home Economics was under the Division of Arts and Languages. In the 1963 - 1964 course catalog, it became the Department of Home Economics and Family Living, as part of the Division of Arts and Sciences. The department chair that year was Beulah V. Gillaspie, and the major had its own building north from Bellflower Boulevard and Seventh Street.

The Department of Home Economics was still educating both men and women in “enhancing the quality of individual and family life,” according to the 1992 CSULB yearbook.

In an article from the archives of the Long Beach Current, formerly the Daily Forty-Niner, the Current reported “the Department of Home Economics will become the Department of Family and Consumer Sciences.” That department name has remained and the Bachelor of Arts degree has changed from Home Economics.

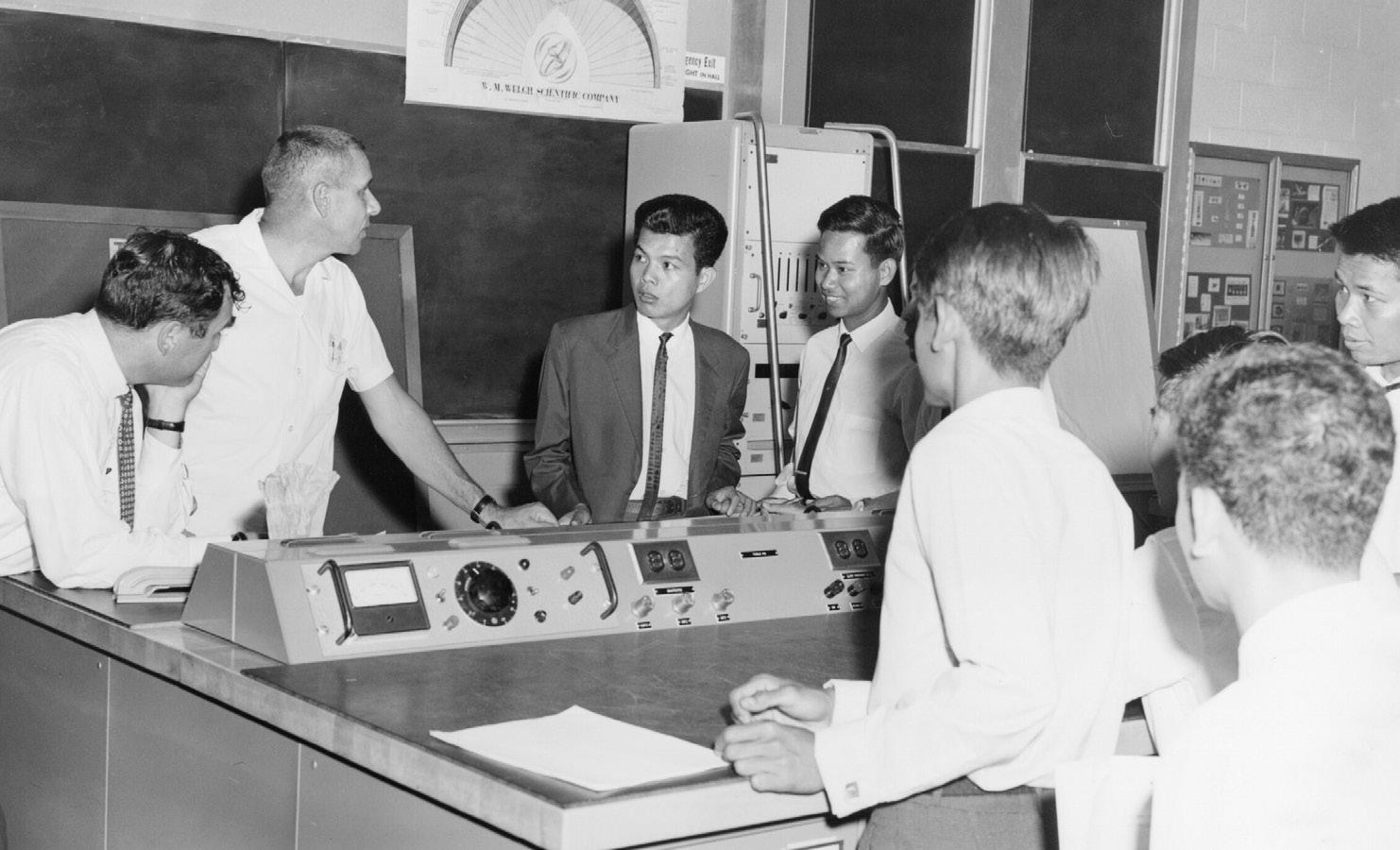

Cambodian students worked along CSULB professors in the Industrial Arts major to learn new ways to do things. This program ran for over five years.

In the same 1950 CSULB yearbook, Industrial Arts was a major. According to the 1971 - 1972 catalog, the Industrial Arts Department had Irvin T. Lathrop as its chairman. By the 1995 CSULB yearbook, there were no students who graduated with a degree in Industrial Arts.

Despite that, during the years of 1963 - 1968, Industrial Arts put together the Cambodia Participant Training Program. According to archives, and documents from Long Beach State Col-

lege’s first Cambodian Cooperative Participant Training Workshop paperwork, the objective of the annual program was to help students from Cambodia develop the ability to work as a professional group and to develop leadership abilities.

The 1963 workshop papers said the program was focused on presenting “discussions devoted to the philosophy and development of technical education as well as to provide for visits to cultural, educational and recreational centers.”

These two programs and departments are just a few examples of the way the college has shifted and changed.

CSULB President Jane Close Conoley said the reason the college continues to evolve is due to students and their success. According to Conoley, a consulting group interviewed students, staff and faculty and returned with the response of student success being key.

“So that was where we came up with the notion that some of our uniqueness was based in our student centric approach,” Conoley said.

BY ACSAH LEMMA Editor-in-Chief

Three years after a settlement between the tribal nations and Long Beach State was reached, Puvungna still has no official steward.

The settlement came out of a lawsuit filed after CSULB dumped “6,400 yards of construction dirt and debris” on the site in 2019.

The suit was filed by the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation – Belardes and the California Cultural Resources Preservation Alliance, Inc., according to a settlement update from Shute, Mihaly and Weinberger, an environmental public interest law firm.

The lawsuit was eventually settled in September 2021 and requires the university to document a Declaration of Restrictive Covenant, which prohibits them or any future landowners from developing on or damaging the land.

The covenant also allows the Tribal groups to continue to use the land for their ceremonies and other traditional activities.

The settlement agreement additionally requires CSULB “to use best efforts to establish a conservation easement over the site in the future.” This would replace the restrictive covenant and “shift care of the land to a manager agreed upon by the settlement parties.”

According to Joyce Perry, the cultural resource director for the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation – Belardes, the university entered a good faith agreement that a land manager would be chosen in two years, but three years have passed and none has been chosen.

Friends of Puvungna, an Indigenous-led organization, has been dedicated to caretaking Puvungna since its formation in 2019, according to the organization’s president Rebecca Robles.

Friends of Puvunga hosts regular clean-ups, traditional ceremonies, food basket drives and more.

Robles was born and raised in north

LINSEY TOWLES for DIG Magazine

Puvungna is considered the place of creation for several Southern California Tribal nations.

Long Beach and said her family has been working to protect Puvungna since the 1990s.

Puvungna is the sacred site for the Acjachemen, Gabrielino-Tongva and several other Southern California tribal groups, located on the edge of campus near the Earl Burns Miller Japanese Garden.

Enveloping the entirety of the university, Long Beach and other parts of Southern California, the designated area on campus is what’s left of Puvungna since the development of the city, campus and more.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974, Puvungna is seen as the place of creation for the tribes and where all living things transitioned from spiritual form to physical form, according to Robles.

“We became bodies at that place, and we see new instructions on how to pro-

ceed as humans,” Perry said. “It is our Mecca, our Jerusalem.”

Robles said if Friends of Puvungna gets awarded the easement, the organization would be the official stewards. As of now, they are considered voluntary caretakers.

When the university released a Request for Proposal last spring for the stewardship of the site, Friends of Puvungna submitted a proposal and was denied for conflict-of-interest reasons.

The one-paragraph response gave no other reason.

When asked to elaborate on this, Associate Vice President of University Relations Christopher Reese said, “An RFP released earlier this year did not proceed with any bidders. We are now in the process of redrafting the RFP to better describe necessary qualifications and will release a new version when the language is ready.”

When asked for a response, Jeff Cook, associate vice president of Strategic Communications said, “That is the extent to which the University would have something to share at this time.”

According to Perry, Friends of Puvungna went above and beyond to meet the requirements of the RFP and said she wants the university to keep its word.

“We had to sue them and we’ve been very patient, we’ve been very respectful. We have worked diligently to work within their system, but for some reason, their system is not working well. And so, we’re just hoping to put some kind of pressure and get some answers and get this completed,” Perry said.

If eventually awarded the stewardship, Robles said Friends of Puvungna wants to restore the sacred site to “a place of healing, a place of learning, a place of sharing our culture and a place of justice.”

BY CHRISTOPHER CHAN Contributor

Deep breath in. Lips tight against the mouthpiece.

Fingers positioned on the trumpet’s valves— it’s showtime.

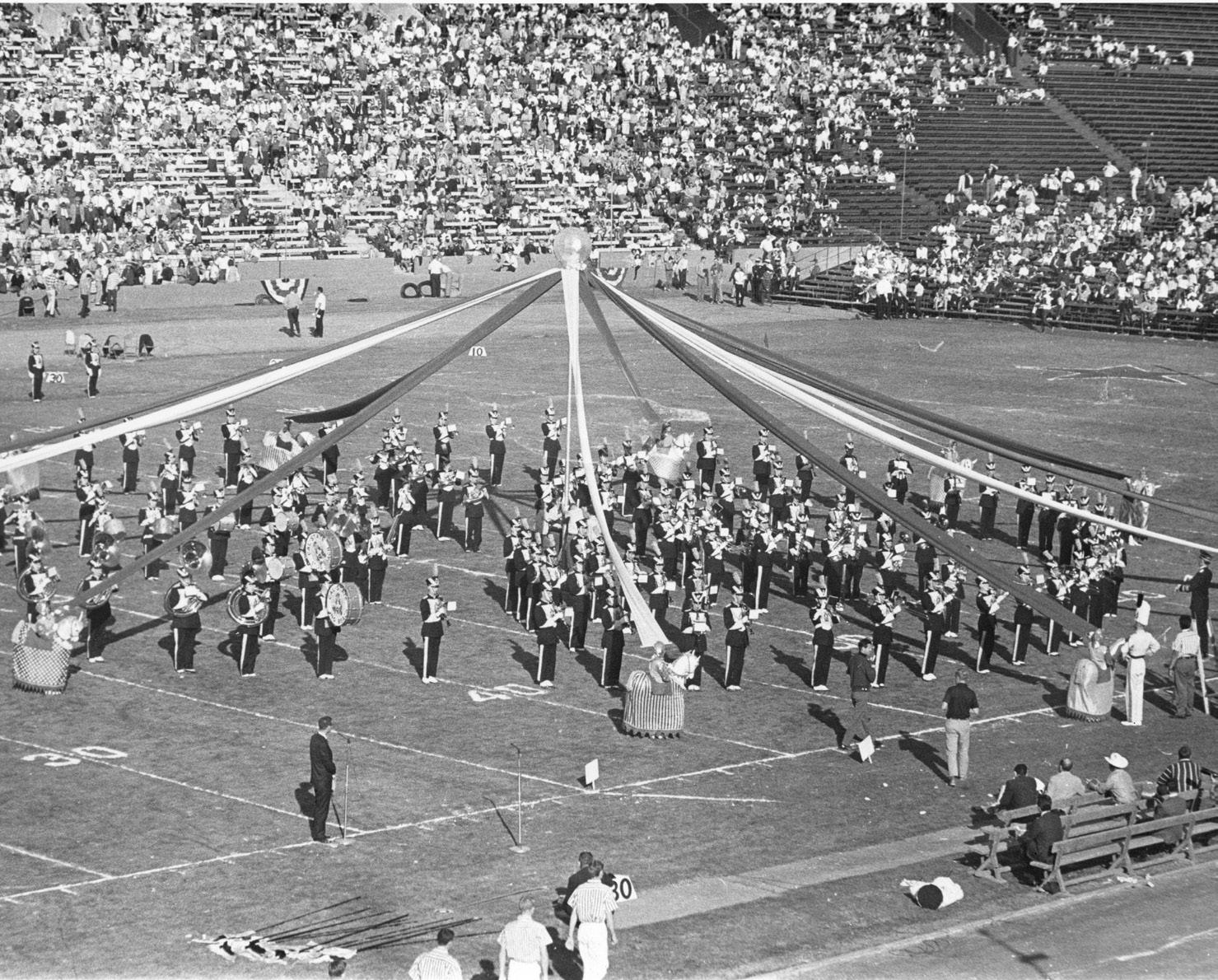

For decades, Long Beach State’s music program has shaped the careers of students, including accomplished alumni Richard and Karen Carpenter, setting an educational standard with its rich and impactful repertoire. The program’s legacy continues to inspire, as reflected in its multiple Grammy-winning alumni.

“One of the things I noticed when I came to visit was this culture of comradery and support for one another that was here and we continue to build on that,” Jermie Arnold, director of the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music, said.

A staple of the program, the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music has been a place where student creativity and artistic growth thrive, a place where an award-winning culture was established by the program’s original band and a place where creativity shined from the start.

First formed in 1949, the program’s original band struggled with frequent leadership changes in the music program, leading to periods of instability. For some time, they lacked a Director of Bands and instead had five different conductors, all primarily hired to teach music education rather than to lead the band full-time.

Despite the bumps the first official concert was held six years later.

On May 10, 1955, student performers showcased a selection of wind instruments, including flutes, clarinets and trumpets.

While classical music was the focus of the original music performed, over the years the program has advanced to incorporate genres like jazz and marching band music. Genres that students like Josh Encarnacion, a 19-year-old firstyear piano major, believe have brought great experiences.

“Having so many genres is great because it makes music accessible to every -

Long Beach Public Library Digital Archive

The Long Beach Marching Band performing at the L.A. Coliseum Pro-Bowl game in 1965.

one who wants to learn about it,” Encarnacion said. “The fact that the program provides so many different opportunities to explore those types of music guarantees that there will be something for everyone.”

Despite its musical milestones, the program faced significant challenges, relying on repurposed science halls for practice and as classrooms— both being makeshift spaces that are not ideally designed for music.

Ultimately, the construction of the BCCM main building in 2003 and the pavilion and plaza in 2007 meant students had a dedicated safe space designed specifically for their musical pursuits.

The state-of-the-art facility offers students practice rooms and student lounges.

“We have an outdoor eating area where students will hang out here pretty much all hours of the day,” Arnold said. “A whole bunch of them were up there singing, having a good time– they may have been practicing for a class.”

Since then, the program has evolved into an environment where students like Encarnacion thrive, inspired by those who came before him.

For some students, the prospect of joining the ranks of accomplished alumni such as John Bettis, a songwriter with multiple platinum records, is alluring.

“We got critiqued by a Long Beach director a couple of times when my high school performed, which gave me more exposure to the program,” Encarnacion said. “I did more research and found out many good musicians came out of it, like Tom Cubis, a great band leader.”

Even today, alumni accomplishments are reaching a different generation of artists.

Soon at Long Beach, trumpet notes will embrace yet another musical style: mariachi. The introduction of this new course aims to further develop the diversity of the BCCM once again, offering a wider range of music available for both current and future musicians on campus.

“There is a place for all kinds of music,” Arnold said. “For every artist to express themselves in a free and open way is important, and we need to make sure we allow that.”

BY JAYLYN PRESLICKA Solutions Editor

Ron Arias came to Long Beach State as a transfer student in 1969.

Phyliss, his girlfriend at the time who later became his wife, had informed him of the Chicano student movements happening across California campuses. Looking for a place to celebrate and learn more about his own identity, Arias enrolled at Long Beach State.

“The Chicano student movement was in its infancy, it was just beginning,” Arias said. “In the late ‘60s, probably ‘67, was probably when we [United Mexican American Students] first started to organize in University Campuses.”

In 1969 the United Mexican American Students organization was trying to increase its membership numbers.

Arias said at the time, there were only around 400 Mexican-American students out of the twenty-plus thousand total student body.

With more underrepresented and minority students taking advantage of the Educational Opportunity Program, a program started by disadvantaged students, more Mexican-Americans were able to attend colleges and universities to attain higher education.

As Arias remembers, CSULB was one of the first campuses of the California State Universities to start a Chicano studies department.

This was due in part to the help of UMAS, which later became Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán or MEChA, the department was instated and students were able to learn about their cultural heritage in an academic setting.

“Once a month, we [EOP students] would go to a Saturday morning meeting to discuss various issues. What it ended up doing was creating a very large organization made up of Blacks, Chicanos, Indigenous people and Asians [who] got to know each other and each of the student organizations were doing the same thing,” Arias said. “They were establishing academic departments, engaging in recruitment and also very involved in retention.”

The Long Beach chapter of MEChA’s main purpose was to spread awareness to other Mexican-American students and offer them the opportunity to join the organization. They would reach out to graduating high schoolers, urging them to attend CSULB.

Their group also hosted seminars with Arias mentioning the importance of the week-long event Seminario De Raza, which included revolutionary speakers such as Cesar Chavez and Angela Davis, among other events to help the Chicano community, on and off campus.

The Chicano student movement was also involved in the Anti-War movement in the ‘60s, focusing a great effort on opposing the Vietnam War. Many students during the time were at risk of being drafted, so the Anti-War organizations promoted a full-time student status to require 16 units as well as keeping above a 2.0 GPA. This protected their student deferments, keeping them away from the draft.

“The background of what is going on in the late ‘60s [is] the overwriting of

the Vietnam War. The backdrop of most of what we were doing had a connection to the Vietnam War. [...] Most of the students that had a consciousness were trying to avoid being drafted, kept their grades up and their units up to the necessary required number,” Arias said.

The Long Beach Current, formerly the Daily Forty-Niner, reported on these events in great detail. Arias said that the student newspaper was there to cover a majority of the events and that there were a few members of MEChA on the news staff.

“They [the Daily Forty-Niner] covered everything, they were an exceptional student newspaper even back in the day. [...] The Forty-Niner was always excellent in terms of coverage,” Arias said. “We [MEChA] had differences with the university and all these stories were covered.”

Arias himself has made great impacts on the Chicano community even after his graduation. He is a retired director of the City of Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services who has established several Long Beach health and research programs.

As an honored member of the community, he was awarded the 2006 CSULB Distinguished Alumni Award for Health and Human Services.

“One of the benefits that they offer outstanding alumnus [is] to participate in one of the many graduation ceremonies. So, I was invited to participate in the graduation ceremony for Health and Human Services,” Arias said. “That graduation ceremony was the most powerful thing that I have seen at Long Beach–ever. It was because of the extraordinary number of ethnic students that were graduating. It made me cry, I was just so overwhelmed.”

Arias is one of the few remaining members of the original Chicano student movement.

His impact, as well as the impact of the others who marched alongside him, has impacted future generations of Mexican-American students.

“It is a great history, it really is. It was great to be a part of it. It’s still part of me, these kinds of things don’t leave you, they make you who you are,” Arias said.

BY JULIA GOLDMAN Arts & Life Editor

On April 4, 1968, the Daily 49er ran two stories on their front page in response to Long Beach State’s Black Student Union protesting a lack of representation in student government.

The headlines read: “Blacks hold [Associated Students] Senate hostage” and “Wrongs don’t get rights.”

74-year-old Erroll Parker, a self-described community activist, said both articles provided examples of the institutional racism and plight that Black students faced during his time at CSULB from 1968 to 1972.

“It shows you the lack of sensitivity white students had towards Black young people,” Parker said.

A Detroit, Michigan native and Los Angeles City College transfer, Parker was one member in the second cohort of underrepresented minorities to be admitted to the Beach campus through the Educational Opportunity Program.

Parker said he spent his time on campus storming the academic senate meetings to demand fair treatment both academically and socially.

His legacy lives on within his role as a BSU Elder, an EOP advisor and recruiter and through his part in starting the Black Studies program, the Africana Studies Department.

During his time as a student on campus, Parker said that a majority of the student body was white.

“I would say that 60% of the student body was white. 15% Asian, 15% Black, 10% Latino,” Parker said.

Fourth-year consumer affairs major Daniel Salcedo said he believes the landscape for the current student demographics has shifted from the study body in the ‘60s and ‘70s as a larger variety of cultures, religions and ethnicities are represented.

GOLDMAN / Long Beach Current Erroll Parker stands in front of the Go Beach sign on Sept. 12. Between a full load of classes, Parker played basketball, was a leader in the Black Student Union, studied journalism and went on to write for the Daily Forty-Niner.

“In my studies, it’s pretty diverse - it’s not just one gender or ethnic group,” Salcedo said. “It makes being in class more enjoyable because you get to experience different viewpoints on the topics.

Third-year music education and performance major Janet Cisneros compares her experience at Long Beach State to her previous colleges, Azusa Pacific University and Cerritos College.

At Azusa, Cisneros said she was one of a few Latina women working at her school’s library.

“They would mix up our names - she thought it was funny, but it was not,” Cisneros said. “We have a right to be called by our names. I’m not this person, I’m Janet.”

Although her friends and family were rooting for her at Azusa, Cisneros said it did not work out. Coming to Long Beach State, however, was something she always wanted.

“When I was finally here, I was like this is where I was supposed to be in the first place,” Cisneros said. “There’s encouragement, dedication and mentorship while also instilling discipline and accountability to be good musicians and teachers and educators. I’m happy I’m here.”

Daily Forty-Niner Archive

The Daily Forty-Niner’s published issue on April 4, 1968, the day after Martin Luther King Jr. died. One month later, the publication ran an advertisement for a “Peace Medallion” with MLK’s face across it, selling for $2.98.

BY LINSEY TOWLES Managing Editor

The history of Long Beach is one rooted in the discovery of oil, the subsequent construction that followed and the establishment of the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

The city of Long Beach was established in the 1880s, with a sprinkling of homes and schools in the area. The dis-

covery of oil in 1921 triggered a boom in population and laid the building blocks for the city we know today.

1949 marks the founding year of Los Angeles-Orange County State College and the college’s newspaper, the Daily Forty-Niner. Both still survive today but under different names.

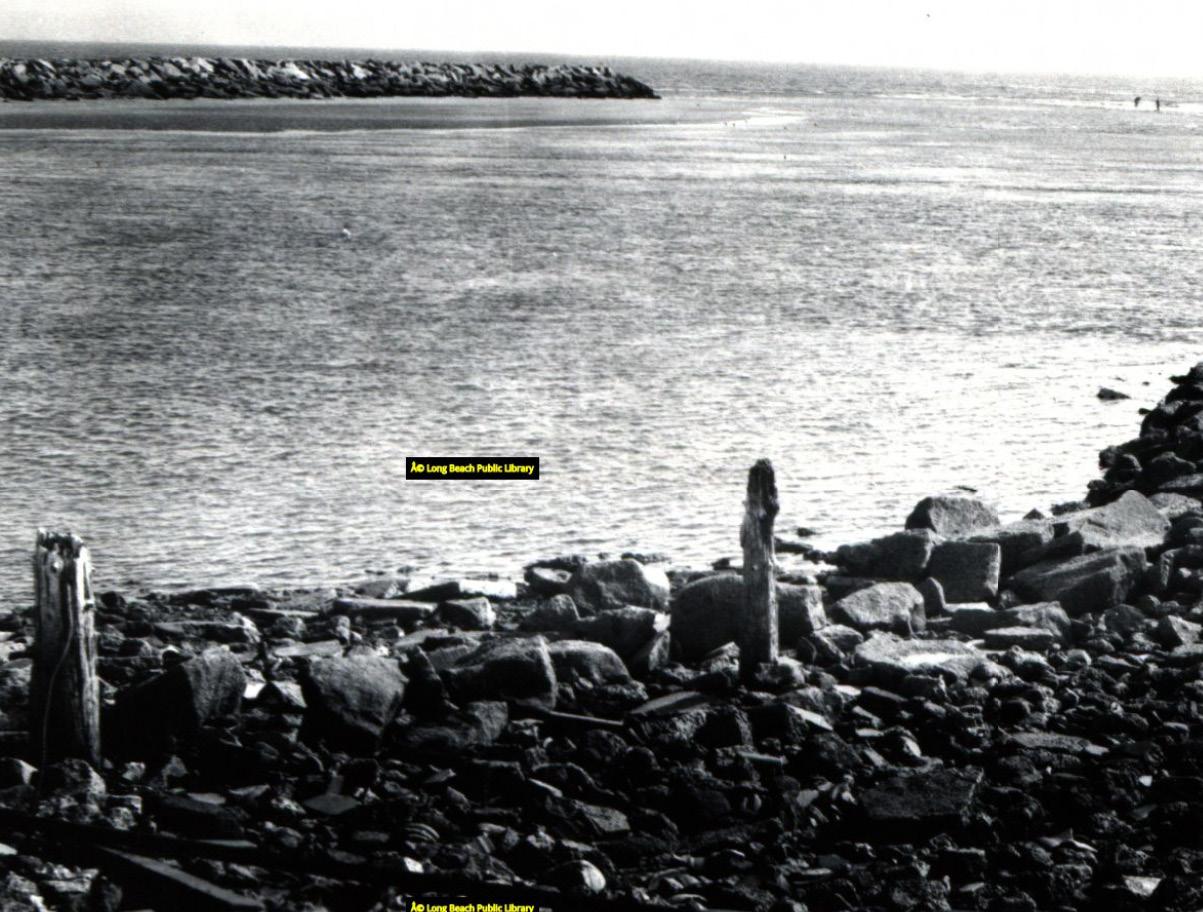

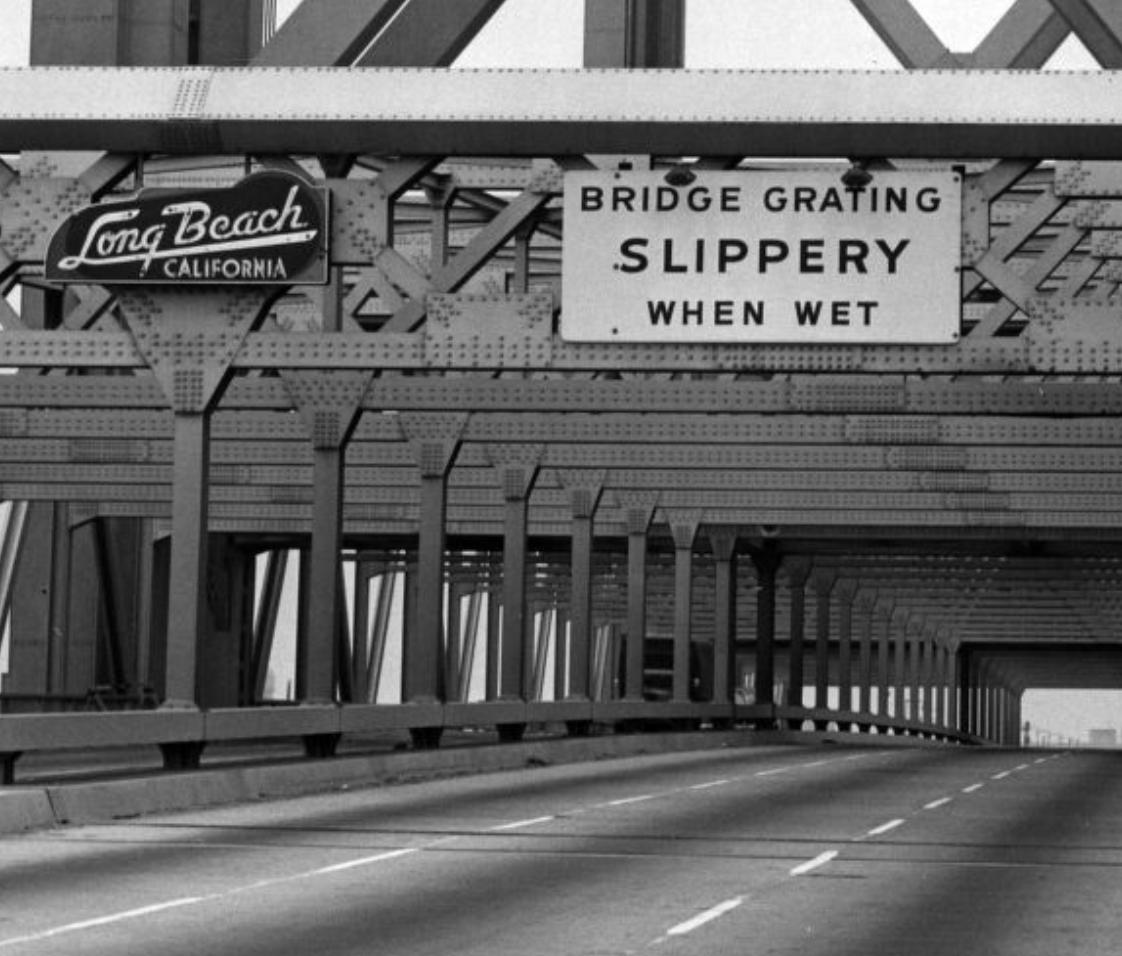

To commemorate 75 years of existence, the Long Beach Current takes a look back at the sights of Long Beach in 1949 from city and school archives.

Clockwise from top: This photo is taken from the west jetty, looking southeast toward the east jetty at Alamitos Bay. The 2.5 mile east Long Beach breakwater finished construction in 1949, which changed the way water flowed at the mouth of the L.A. River; While Long Beach State was the new school on the block, Long Beach City College was founded in 1921. The image shows an aerial view of the mission revival style buildings of early LBCC in 1949 surrounded by undeveloped land; The Jacobsen Pilot Station, pictured here, became the first station in the Western Hemisphere to install a shore-based radar system in 1949; With the population of Long Beach approximately 250,767 by the end of the 1940s, according to the Los Angeles Almanac, small stores like the Dollar Market were needed. This photograph from 1949 shows the northeast corner of Orange Avenue and Carson Boulevard; An aerial view looking east from Bay Shore Avenue in Belmont Shore to Naples, the peninsula and Alamitos Heights oil wells in 1949; While this photo of the Terminal Island roadway across the Commodore Schuyler F. Heim Bridge, which spans the Cerritos Channel was taken in 1957, the “Long Beach, California,” sign was installed in November 1949.

BY DANTE ESTRADA

Video Editor

years ago, the Los Angeles-Orange County State College commenced its fall semester in the dining rooms, kitchens and living rooms of a small apartment building at 5401 E. Anaheim St.

Within the following years, campus populations grew and buildings were constructed to represent the familiar Long Beach State of today.

Notably, Liberal Arts buildings 2 and 3 are some of the earliest buildings to have been built as part of a plan to expand and renovate the college. By 1954, the structures were complete.

Jesse Odell, a lecturer for the Department of Comparative World Literature and Department of Romance, German, Russian Languages and Literature has

taught at CSULB for five years.

All of their courses, Odell said, have been hosted in Liberal Arts 2 and Liberal Arts 3.

“The classrooms in the main buildings are more comfortable than many others on campus, and the cinema-style screens in the separated buildings are ideal for teaching courses on film, television and other forms of visual media,” Odell said.

Odell said that this semester, they are teaching a HyFlex course, which combines in-person and online learning. The resources held in Liberal Arts 2 are helpful to Odell, including the technology in the classroom.

“The instructor options and controls are helpful and intuitive, and I appreciate that there are multiple camera angles and microphones built into the system,” Odell said.

The College of Liberal Arts is the largest college on campus according to the CSULB website, with over 30 various departments and programs. With

Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives

A photograph of the Liberal Arts 2 and 3 buildings in 1959, following its construction.

departments ranging from communications, geography and various foreign language programs, students can broaden their knowledge via several avenues of degrees.

Since 1954, the sustained infrastruc-

To request disability-related accommodations, complete the Bob Murphy Access Center Event Request Form at asicsulb.org/calendar.

ture of the five Liberal Arts buildings has served the faculty and students toward their educational dreams. As its constituents continue to pass through its raised pillars between classes each day, its tradition shall continue.

BY JOANNAH CLEMENTE Opinions Editor

As Long Beach State celebrates its 75th anniversary, the success of the No Barriers campaign reaffirms its longstanding pledge to student support.

Exceeding the initial target of $275 million, the initiative raised over $313 million from 58,000 benefactors, marking a transformative moment in the institution’s business trajectory.

This achievement represents the collective effort and innovative leadership required to propel student progress and promote inclusivity.

For students, these contributions translate into practical benefits, enriching their academic experiences and unlocking new opportunities.

CSULB President Jane Close Conoley emphasized three core principles that shaped this campaign: student empowerment, workforce preparation and community good.

These values have been instrumental in broadening the campaign’s impact across the university.

Anchored by these student-focused priorities, the initiative will continue to elevate the educational landscape and provide sustained aid for future generations.

Recognizing the milestones achieved by the No Barriers campaign offers a holistic view of CSULB’s growth and outlines its philanthropic vision for the years ahead.

One notable endowment, highlighted by Conoley, was from Laurén Chalmers, class of 1983, who established the Associated Students Inc. Beach Pantry.

“She has endowed our ASI pantry that will spin off about $60,000 a year to buy groceries,” Conoley said. “The pantry supports thousands of students.”

This level of generosity, coupled with strategic-building efforts, is what Daniel Montoya, vice president of University Relations and Development, attributes to the campaign’s success.

No Barriers, a vision set in motion in 2016, paves pathways for student success at CSULB.

Montoya explained that the campaign, which began around 2016, was built on effective communication and relationship cultivation.

“Associate Vice President Jeffrey Cook’s strategic communication is the entryway into which people see the university,” Montoya said. “Donors choose methods to engage with the institution, and the rest of the team follows to develop relationships that lead to gifts.”

Identifying strategies to boost student life, as demonstrated by Cook’s approach, deserves appreciation for showcasing the institution’s commitment to student welfare.

Cook further likened the relationship between the university and its supporters to a partnership, emphasizing the cooperation between institutional objectives and donor goals.

“There’s always a marriage between an institutional perspective and priorities, and then where donors really want to make their mark,” he said. “It’s a testament to how donors stepped up and affected change in supporting our educational mission and students.”

Given the scale of the campaign, it can be seen as a symbolic gift to honor the university’s 75th anniversary.

This landmark event will be etched

in the institution’s history, serving as a source of pride for all involved.

“Everybody loves to support a winner,” Montoya said.

CSULB’s philanthropic culture has strengthened its standing among students and the community, cementing its role as a vital institution.

It not only elevates the university’s reputation, but sets a strong precedent for future charitable efforts.

With this momentum, CSULB is poised to inspire alumni, attract sustained support and lead attainments that will mold student lives and amplify its prestige for years to come.

We’re proud to celebrate the 75th anniversary of California State University, Long Beach and the Long Beach Current!

The College of Professional and Continuing Education (CPaCE) is grateful to be a part of a campus community that has benefitted so many students, alumni, faculty, and staff. We’re especially thankful for the long tradition of student journalism culminating in this special milestone issue.

As a hub for lifelong learning, CPaCE provides different educational needs at every step of a person’s journey—from young adults entering the workforce, to experienced professionals upskilling for career transitions, to retirees seeking personal enrichment. We offer a diverse range of online and on-campus programs at www.cpace.csulb.edu.

We look forward to enjoying many more years of enriching learning experiences at The Beach!

BY CHRISTINE NADER

Opinions Assistant

In the past 75 years, campus life and culture at Long Beach State has become an intricate tapestry of student activism, inclusion and pride.

Service-providing organizations on campus like the Isabel Patterson Child Development Center and Project Rebound are a couple highlights of kindness on campus.

The Child Development Center was founded in 1975 after a generous donation from alumni Isabel Patterson, for whom the center was eventually named after.

Patterson’s deep love of caring for children lifts the weight off of CSULB students with children by providing them the peace of mind and time to focus on schooling.

According to CSULB professor Barbara Kingsley-Wilson’s book, “Long Beach State at 75,” Patterson was impatient with college officials who were taking their time in building a toddler and infant facility in the care center.

Patterson urged college officials to speed up the process of construction, and the toddler and infant center was finally completed in 1994.

Founded in the ‘70s, Project Rebound is a CSU program assisting formerly incarcerated individuals who aim to further their education through a bachelor’s or master’s degree.

Project Rebound joined the Beach toward the end of 2020 and since then have supported 95 students. They guide students through filling financial aid forms, provide services like CalFresh expungement and advocate for students with difficulties in parole or probation.

In 2024, CSULB’s student organizations have been consistently vocal in calling for public support from students regarding issues on campus.

La F.U.E.R.Z.A (formerly known as

“We organized all the student organizations who frequent the resource centers to come and speak with President Conoley. It was successful.”

We organized all the student organizations who frequent the resource centers to come and speak with President Conoley. It was successful.

Pedro Garcia

La F.U.E.R.Z.A spokesperson

La Raza in the ‘70s) is a student organization that focuses on political and cultural issues. The organization was founded in 1968 to educate the students on campus and demand for change.

The media spokesperson for La F.U.E.R.Z.A, Pedro Garcia, who is using an alias for safety reasons, recalled a mo-

ment where he halted the relocation of the La F.U.E.R.Z.A resource centers to the basement of the campus library.

“The administration never spoke to students about what our needs were and spent our tuition money to hire a designer without notifying any of us,” Garcia explained.

La F.U.E.R.Z.A is consistent in continuing the legacy of their predecessors. They have been seen protesting tuition increases and advocating for undocumented students.

While there have been many positive changes to campus, the university has their fair share of criticism.

Over the past two years, the general consensus of dissatisfaction expressed from students is centered around the increase in parking permits and fees, dorming issues, lack of facility repairs like the escalators and lack of support toward the marginalized communities.

CSULB has evolved greatly over the years, both as a physical establishment and regarding policies– but there is still a long way to go.

BY MATTHEW COLEMAN Sports Assistant

Any list or form of power rankings is completely subjective, and up for debate. It’s what makes these discussions so polarizing because people value different aspects of individual careers when comparing them.

Before going into my list, I’ll lay out the parameters I set before constructing. This is solely based on their playing career at LBSU, there are no coaches, or players that transitioned into coaching careers that added to their legacies.

All the players listed must be members of the Long Beach State Hall of Fame. This immediately disqualifies players like 1998 NFL MVP and Super Bowl XXXII MVP Terrell Davis (though he did shout out The Beach during his 2017 HOF speech in Canton).

Or recently graduated men’s volleyball libero Mason Briggs, who very well has the résumé to be considered, but is not yet a member of the LBSU Hall of Fame. He’ll have to wait for the one-hundredth anniversary special for his spot on the coveted unofficial top 10 list.

10. Erin Jones-Wesley - Softball

Jones-Wesley has her name written all over the Long Beach State softball record book. She sits atop the program leaderboard in both wins with 84 and 728 strikeouts in four seasons. Along with leading The Beach to a pair of Big West titles and three trips to the NCAA Tournament, she tossed three no-hitters.

9. Evan Longoria - Baseball

Manning the hot corner at Blair Field at Bohl Diamond for the Dirtbags for two seasons, third base Longoria slashed .336/.419/.506 with 16 home runs and 73 RBI. In 2006, he finished as a finalist for the Golden Spike Award, given to the best player in college baseball, and was named Big West Co-Player of the Year. Longoria became the highest-drafted Dirtbag in school history when he was selected third overall in the 2006 MLB Draft by the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

8. Antoinnette White - Women’s Volleyball

The 1991 AVCA Player of the Year is one of four women’s volleyball players at Long Beach State to have her number in the rafters at the Walter Pyramid. White was a member of the first NCAA championship-winning team in 1989. She holds

Courtesy of LBSU Athletics

As a major leaguer, Evan Longoria was named AL Rookie of the Year in 2008 and named an all-star three times, winning two gold gloves and a silver slugger award at third base.

the single-season record for service aces in a season with 91 in 1990.

7. Lucious Harris - Men’s Basketball

Harris finished as LBSU’s and the Big West Conference’s all-time leading scorer (2,312). He also holds the single-season Long Beach State scoring record with 739 points. The offensive powerhouse led the 49ers to their first NCAA tournament appearance in 16 years after being voted Big West Tournament MVP in 1993.

6. Brent Hilliard - Men’s Volleyball

During Hilliard’s tenure at Long Beach State, he led the 49ers to a National Championship victory in 1991, beginning a three-year stretch of being named first-team All-American. 1992 was his best season, as he earned National Player of the Year honors. Hilliard sits atop both the LBSU and NCAA record book with 3,034 kills. In 1991 he set an NCAA record with 821 kills.

5. Hannah Grady - Women’s Tennis

also sits atop the list in starts (55), innings pitched (370), strikeouts in a game (17) and consecutive wins in Dirtbags history.

The 14 consecutive wins he compiled were to start his historic 2004 season, where he led the country in wins (15) and strikeouts (213) on his way to becoming the first-ever Dirtbag to take home National Player of the Year honors.

2. Danielle Scott - Women’s Volleyball, Basketball and Track & Field

Not only did Scott earn All-Big West honors on the hardwood, averaging over 17 points per game and leading the league in rebounding. She also competed in several events at the Big West Championships for Track and Field.

However, it was volleyball where Scott truly left her mark at LBSU. Anchoring the middle, Scott was named an AVCA All-American three times, finishing off her career as 1993 AVCA Player of the Year and helping the 49ers secure their second NCAA title. Scott led Long Beach State to three consecutive trips to the Final Four.

1. Misty May - Women’s Volleyball We made it.

The No. 1 spot belongs to one of the true icons of the sport, it is hard to argue that Misty May is not just the G.O.A.T. of Long Beach State Athletics, but volleyball in general.

Grady dominated competition during her four-year career at LBSU. She is the only athlete in Big West history to win Conference Player of the Year four times. Standing alone as the only player in Long Beach State history to receive multiple invitations to individual NCAA championships. After her career, a court at the Rhodes Tennis Center on campus was renamed in her honor.

4. Tara Cross - Women’s Volleyball

One of three former Long Beach State players named as the six greatest collegiate players of all time in 2001. Cross was a four-time All-American and named the AVCA Player of the Year twice. She led LBSU to their first NCAA championship in 1989.

3. Jered Weaver - Baseball

The all-time ace of the Dirtbags, Weaver put up video game numbers on Friday nights at Blair Field at Bohl Diamond. Weaver holds the Long Beach State and Big West conference record in both wins (37) and strikeouts (431). He

The accolades May accumulated during her four years at LBSU are remarkable. Starting off by winning Big West Freshmen of the Year, earning three Big West Player of the Year awards and being named All-Big West First team four times.

The two-time AVCA Player of the Year led LBSU to their first undefeated season in 1998 (36-0) that ended with the 49ers winning their last women’s volleyball NCAA title to date. May is the recipient of the 1998 Honda Broderick Award, given to the best female collegiate athlete across all sports.

“Antoinnette White, Tara Cross, Danielle Scott, those are players that I idolized, and they’re the reasons why I wanted to go to the school. So it’s special to be up there with them,” May said. May is second all-time in collegiate women’s volleyball in assists (5045), aces (160) and third in digs (1277). She tallied a career-high 87 assists in 1998 in a single match. Her post-Long Beach State career is as decorated as anyone. May is a three-time Olympic gold medalist and FIVB champion in beach volleyball.

BY ALYSSA DE LA CRUZ Sports Assistant

From the courts to the pool, Long Beach has produced athletes who have transformed their sports and left a lasting mark on the world stage.

Among them are Misty May-Treanor and Danielle Scott-Arruda, volleyball icons and LBSU alumni, alongside Susie Atwood, a Long Beach native and a twotime Olympic swimmer.

Few athletes in the history of volleyball can compete with May-Treanor’s resume after an extraordinary collegiate career where she led The Beach to NCAA women’s volleyball’s first undefeated season and championship.

May-Treanor made her mark on the global stage in beach volleyball while partnering with Kerri Walsh Jennings. The duo won three Olympic gold medals (2004, 2008, 2012) and became the most decorated team in the sport.

“It is a memory that will always play in the back of my mind when the national anthem plays, but that one especially to bring home a gold for U.S. women’s volleyball as a whole,” May-Treanor said.

The pair set various records throughout their partnership, including a winning streak of 112 consecutive matches in 2007–2008, breaking their previous record of 89 consecutive match wins.

“You know, families, we were like, ‘Why doesn’t Kerri just come out to the beach and just try and see if she likes it or not?’” May-Treanor said. “So she came out and tried the beach and then never looked back.”

Even after a ruptured Achilles tendon on Dancing with the Stars and doubts from many, May-Treanor returned to competition and went on to win another gold.

“When you’re part of a team, the team believes, and the coaches believe that’s all you need,” May-Treanor said.

As a cornerstone of LBSU’s success in the early 1990s, Scott-Arruda led The Beach to the 1993 NCAA National Championship and earned National Player of

the Year honors for both volleyball and basketball. She became the first Big West student-athlete to earn all-conference accolades in two sports in one season.

“It was really special for me to be able to bring my daughter back there and say, ‘Hey, that’s my number retired there,’ “ Scott-Arruda said. “People see my picture or my name, they think of someone who you know was dedicated and worked hard as a team player.”

Her remarkable collegiate career set the stage for international success as she went on to represent the United States in five Olympic Games (1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012,) a record for U.S. female indoor volleyball players. She is one of six players in the world to ever accomplish the feat and is a two-time silver medalist.

After her third Olympics and a fifthplace finish, she walked back to the village reflecting on her performance, and realized she still had more to offer.

Her dedication to her country was strong, and she felt a deep connection to it, often saying she “bleeds red, white and blue.”

Feeling in shape and confident in her abilities, Scott-Arruda believed she still had more to contribute and would have pursued a sixth Olympic appearance if possible.

While volleyball may reign in Long Beach, Susie Atwood brought global attention to the city through her achievements in swimming. A native of Long Beach, Atwood’s Olympic dream began at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics when she was 15 years old.

“The Olympics had been a goal of mine since I was ten years old,” Atwood said. “I couldn’t believe it, to be with so many Olympians that I admired and still admire...I was now on the same team as my heroes.”

Atwood’s true success came in the lead-up to the 1972 Munich Olympics where she set world records and established herself as one of the top backstroke swimmers in the world.

However, her Olympic performance didn’t live up to her expectations due to a disappointment she attributes to a calculated risk during training.

Susie Atwood, a two-time USA Olympic swim silver and bronze medalist, made waves with her remarkable swimming career, becoming one of the top backstroke swimmers of her time.

Courtesy of LBSU Athletics

Danielle Scott-Arruda, a five-time U.S. Olympic volleyball player and a Long Beach State standout who led her team to a national championship, proudly displays her legacy as a two-time silver medalist. Her career embodies a remarkable journey of skill and achievement in the sport.

“We kind of took a calculated risk of not resting for the Olympic trials, and that was a mistake. With rest comes speed,” Atwood said. “I was happy to be there, happy to get a couple of medals and be a part of the Munich Olympics.”

Despite this, she still earned a silver medal in the women’s 200-meter backstroke and a bronze in women’s 100-me-

ter backstroke.

In 1992, she was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame, an achievement she called the culmination of her life’s work.

“It was a proud moment for me, something that can never be taken away from you,” she said.