MISSISSIPPIAN

In the South, food is synonymous with fellowship. But in what other ways does food impact our lives? In this issue, we explore food culture, food insecurity and dining options.

In the South, food is synonymous with fellowship. But in what other ways does food impact our lives? In this issue, we explore food culture, food insecurity and dining options.

The University of Missis sippi’s Southern Studies pro gram is impacting how food is incorporated into education.

Catarina Passidomo, a South ern Foodways Alliance associate professor of Southern studies and associate professor of anthro pology, hopes that her classes teach students to think critically about food’s impact on society.

“Most of my classes involve teaching about food in some way,” Passidomo said. “In Southern studies, I teach a 100-level class about the South and food which is being offered this spring. I also teach a 500-level class called Southern Food Studies. In both classes we’re talking about how food and agriculture have shaped the South and thinking about how we can understand Southern his tory, identity and culture through food and through the way people talk, write and think about food.”

Passidomo is teaching a winter intersession class called “From Field to Fork: The Con nections Between Food and Place” in which students will

travel to New Orleans. These classes help expand the students’ minds to all aspects of food.

“A lot of ideas people have around food are just about con suming it, so we try to think about food systemically as a com plicated chain of events that all involve people,” Passidomo said.

Food has an impact much further than its taste, Passidomo said, but our society and com munities are heavily impacted by the profit being made off of it

“The primary thing we teach in that class is that the primary function of contemporary global food systems is not to feed peo ple but to make a profit. That’s why even though we produce enough in the world for everyone to eat sufficiently and healthi ly, more than a million people are hungry or malnourished or both. This is because the system was designed to generate prof it for corporations and not to feed people,” Passidomo said.

Students in Passidomo’s “Food, Place and Power” class are producing an oral history project with the community mar ket. They are interviewing ven dors, primarily farmers, some of whom are also bakers to learn

about an alternative food system.

The Southern Studies pro gram at the university drives to challenge the idea of the South and remove precon ceived notions about the region.

“We are interested in com plicating narratives about the South and how the South is not a region set apart from the country but is reflective of the rest of the country and the most American place for better and for worse,” Passidomo said.

The future is bright for pro grams like Southern studies and anthropology and their food focuses here at the university. Southern Foodways Alliance raised money to support hir ing instructors to teach food studies and has made a posi tive impact on the university.

“Our degree has grown a lot because we’re now a part of the academic common market so stu dents from a few other states can get in-state tuition if they major in Southern studies. So that means we have a lot of new majors. The amount of people who are inter ested in studying food seems to be growing,” Passidomo said.

While the future is bright for programs like Southern studies

that focus on food closely in their classes, there is also hope for more diverse programs to begin incorporating this study as well.

“There are a lot of possibilities for food and other educational programs. We have a food policy class within public policy lead

ership, and food studies minor housed in nutrition and dietetics. There are also ways to think about food from a historical perspective. People are even studying food through social media and other virtual spaces,” Passidomo said.

Lenoir Dining, located on the University of Mississippi campus, is operated by hospitality manage ment and dietetics students. Lo cated in Lenoir Hall, this non-prof it restaurant allows students to have first-hand experience in their field while providing qual ity food and service for patrons.

While a majority of Lenoir’s customers are UM alumni, Lenoir is working alongside graduate mar keting classes to attract a younger demographic, such as students.

Hospitality management Ph.D student and undergraduate stu dent instructor Jeffrey Pittman ll describes how Lenoir dining aids in student development.

“Every student comes into Le noir Dining and, at first, they’re scared. They’re scared that they may not cook as effectively. They may not think they are actually

meant for the service industry,” Pittman said. “Chef Dru Jones and I always come through to lead and motivate them to do better. We never yell at them. If they do something wrong in the kitchen, it’s all right. We correct it right then and there.”

Hospitality management and nutrition dietetic students can take the lab NHM 472, in which they can gain experience before they go into the food service industry. In this class, they are taught how to properly and safely cook food, how to operate a kitchen, how to manage the front of house staff and how to conduct sales. Stu dents also have the opportunity to create the menu based on what they would like to learn to cook.

Senior hospitality man agement major Julia Rodig is a server for Lenoir Dining.

“It’s really cool. You get to switch positions every few weeks to experience a new job,” Rodig said. “You can be cooking an en

tree, making salads, serving in the restaurant and even be the kitchen manager. You get a chance to work at every position in the restaurant.”

Since getting involved with the program, Rodig has been able to learn more about the restaurant industry.

“I have learned a lot more about what goes on behind the scenes of a restaurant. I work at a restaurant as a hostess, but ha ven’t really experienced things in the kitchen,” Rodig said. “This class has allowed me to have a better understanding about how much prep and work goes into cooking the food in a restaurant. This class has helped me learn more about the restaurant busi ness and working off it as a whole. It has allowed me to apply things to my job off campus and gave me a better understanding of where I work. Learning from someone like Chef Dru has been so valuable because he has tons of experience and has been to so many places.”

Lenoir Dining hopes to expand its audience by moving locations from Sorority Row — Lenoir Hall is located in the former Zeta Tau Alpha house — to the South Ox ford Center. This will allow stu dents to utilize the large cafeteria and satisfy more of their market. This location also would allow eas ier access to parking for patrons.

Rodig also explained how much she appreciates the atmosphere of the restaurant in Lenoir Hall.

“Our class is fairly small so we’re all friends and work so well together. We help out where help is needed and really work as a team to run the restaurant,” Rodig said. “I love serving because I get to talk to so many people from faculty and staff to Oxford lo cals, and even my brother would come in and eat on some days.”

Pittman elaborated on how the dining experience helps young professionals gain experience and grow.

“It’s my and Chef Dru’s job

to make sure these students stay motivated so that way when they finish the class and they go into the internship and finish the in ternship and go into the real in dustry, they learn from all their mistakes,” Pittman said. “There’s no such thing as getting punished for making a mistake. Chef Dru and I look at mistakes as learn ing opportunities. That’s how we motivate our students … and then demonstrate the correct way. That way they know this learn ing opportunity and they have a visual display on what to do.”

Students and members of the Oxford community can make reservations online Monday through Friday. For $12, custom ers get a four-course meal and a drink. Tips are not required, but any tips received go directly to the organization as a dona tion to help fund the program.

Lab fees paid by the students also work to fund this nonprofit.

Hot flames from a stove in Lenoir Dining, the sound of a steak searing and sharp knives whittling away at vegetables is what chef Dru Jones lives for.

Jones is a food specialist at Ole Miss where he has worked for the past four years. A food specialist is someone who oversees food preparation and ensures that it is pre sented at the highest quality.

His journey with food began back when he was a child, eating good Southern food and TexMex while grow ing up in Houston, Texas.

Being able to cook for a living as well as sharing his skills and knowledge with students drives for ward his culinary career.

“People that do what I do, we all want to work. We love what we do, and that’s why we work a hun dred hours a week,” he said.

Jones didn’t originally go to school for anything food related, it really was a spurof-the-moment decision.

“When I first started cook ing, it was almost out of neces sity,” Jones said, explaining how he stumbled onto food rather than intentionally go ing to study it. “I took a break from school after moving back to Oxford, and I hadn’t eaten in a couple of days, but I knew I was going to start working in a restaurant. And I was hungry.”

Jones learned to appre ciate his time in the kitchen and the ingredients that went into the food, which helped further ignite his passion. He then decided to finally put this knowledge to practice.

To complete an en tire year of school quick er, Jones attended culinary school from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. for three months straight in

the program at Johnson & Wales University in Miami.

After graduation, Jones permanently moved to Flor ida with his wife to begin his career, where he spent roughly 12 years work ing executive chef jobs.

“I was married and had a baby on the way all while working 100-hour work weeks,” Jones said. “I was executive chef at three different restaurants be fore I was 30 years old.”

Jones was already a suc cessful chef early in his life, but he did not want to miss out on time with his family. So he and his family moved to Miami where he went back to Johnson & Wales to teach in one of their food labs and earn his bachelor’s degree.

After a few years work ing outside the restaurant industry, Jones decided to move back to Oxford to be closer to his retired parents. Once the move was com plete, he was asked to join the City Grocery Restau rant Group as the corporate chef at Bouré. Jones moved around within the different restaurants during his fouryear span with the company.

Jones had gone back to working 80, 90, or 100-hour work weeks. After coming home one day from a long shift, his wife informed him that a position in the Depart ment of Nutrition and Hospi tality at Ole Miss had opened.

With 31 years of experi ence, as well as having worked in kitchens across the coun try, Jones believed he was the best for the job due to his culi nary and business knowledge.

“The cool thing about what I do is that I still get to teach and cook. In Lenoir Hall, we have a 40-seat restaurant that I run on campus,” Jones said. “I just get to go home

at night and go to the foot ball games on the weekends.”

He still fulfills his love for cooking while also shar ing his knowledge and ex pertise with students.

“We teach the business side. It’s not all fun and mak ing the food taste good we’re trying to teach people how to manage a business. So when you’re an owner or manag er, you can facilitate that side of it as well,” he said.

The current state of the Department of Nutrition and Hospitality at Ole Miss is heavily focused on the busi

ness aspect of the job. Accord ing to Jones, it’s like train ing for a hotel manager who needs to know what the food they serve should look like.

“This isn’t culinary school,” Jones said. “We’re not training people to be chefs, we’re not training peo ple to wait tables, but we wan na give you that knowledge.”

However, in the fu ture, Jones and the rest of the staff at Lenoir Hall are hoping to expand and pos sibly make the program more culinary-focused.

“Everyone here at Lenoir is

hoping we can expand or get into a new building to get more culinary arts focused courses and even a minor,” Jones said.

Even with Jones’ busy schedule of teaching and cook ing, he still loves every second.

“Some people have to sep arate their work from their passion, but their work will pay for their passion. For me, cooking is all I got. It might not pay much, but it fulfills my need to create.”

For more information on Dru Jones and Lenoir Dining, you can visit their website.

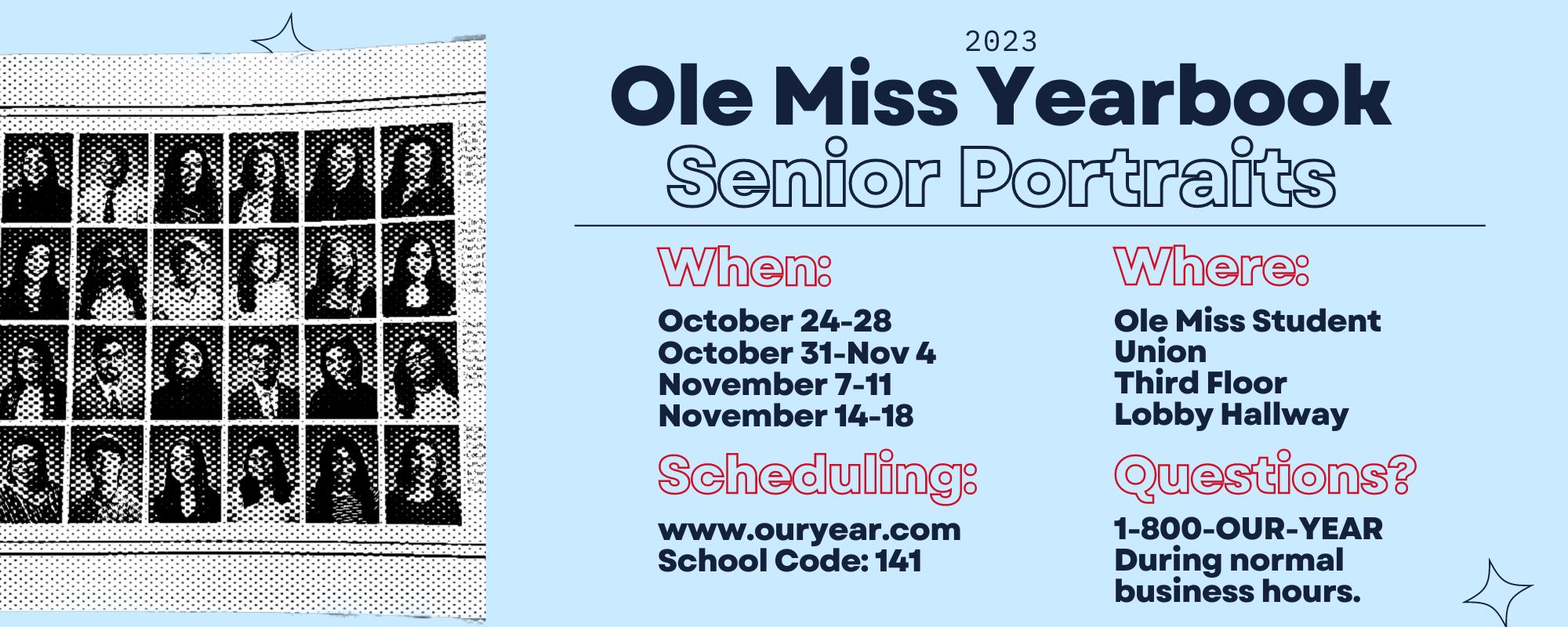

RABRIA MOORE editor-in-chief dmeditor@gmail.com

VIOLET JIRA managing editor dmmanaging@gmail.com

ZACH SPOONER copy chief thedmcopy@gmail.com

HAL FOX MARY BOYTE news editors thedmnews@gmail.com

AIDAN GALLARDO sports editor thedmsports@gmail.com

JANE ROB PANNELL assistant sports editor thedmsports@gmail.com

HG BIGGS photo editor thedmphotos@gmail.com

ASHTON SUMMERS assistant photo editor thedmphotos@gmail.com

JUSTICE ROSE opinion editor thedmopinion@gmail.com

KHARLEY REDMON arts and culture editor thedmfeatures@gmail.com

WILL JONES assistant arts and culture editor thedmfeatures@gmail.com

ERIN FOLEY LIBBY FLANAGAN design editors thedmdesign@gmail.com

SAVANNAH SHOOK SEDLEY NORMAND visuals editors thedmvisuals@gmail.com

CAROLINE BEACH social media editor thedmsocialmedia@gmail.com

BRITTANY KOHNE multimedia editor dailymissmedia@gmail.com

LARZ ROBERTS

Director of Student Media

DENNIS MOORE Editorial Director

ROY FROSTENSON

Assistant Director/Advertising

JAYLIN JONES

Advertising Sales Manager dmads@olemiss.edu

SALES ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Owen Pustell

When it is decided that The Daily Mississippian will take an editorial stance on an issue, the following positions will make decisions as the Editorial Board: editor-inchief, managing editor, copy chief, sports editor and opinion editor.

Thanksgiving is a time for fam ily and friends to join together and vocalize their gratitude for things that often get taken for granted. For some individuals, that ap preciation looks like a healthy dose of home cooked nostalgia prompted by the holiday season.

This rings true for those hours away from their home, but also for those who have found that familiar flavor with in the Oxford community throughout their entire lives.

Sara Ellis Dean is a sophomore biology major from Water Valley, Miss., who transferred to Ole Miss at the beginning of the fall semester. Growing up in Oxford’s neighboring town, Dean became accustomed to a fair summary of what Oxford’s backyard Thanks giving cuisine consisted of — and she is certain of her answers.

“Thanksgiving has to have dressing,” Dean said. “It is a necessity.”

She expanded on her hol iday food essentials by shar ing that an Oxford-adjacent Thanksgiving includes time with extended family compet itively enjoying the Egg Bowl.

“Family is my number one favorite thing about Thanksgiv ing because it’s one of the few times I get to see my distant family throughout the year,” Dean said. “But also the Egg Bowl is every Thanksgiving, and I always know that’s some thing I can look forward to.”

Contrary to her fellow south erner, sophomore accounting major and Nashville native Kath erine Duke said that dressing is a stop she will not make around the table. Duke did, however, confess her love for her Grand ma’s marshmallow-topped sweet potato casserole.

“I have memories of running around the house and being able to smell it as she’s making it and getting excited because I know it’s coming,” Duke said.

Duke said that both sides of her family offer different Thanksgiving food traditions, as they come from different sec tions of the country. None of those, however, are similar to what sophomore accounting major Maddie Arbuckle has ex perienced on the Pacific Coast.

Arbuckle has spent her last two years calling Seattle, Wash., her hometown, but prior to that, she spent many years in Honolulu.

“(Hawaii’s Thanksgiv ing) is heavily Asian influ enced — we have a ton of Asian dishes,” Arbuckle said.

As for her favorite Hawai ian holiday dish, Arbuckle shared that it must be the Fili pino spring rolls known as lum pia, a dish that a family friend makes and that has continued to stick with her throughout the years. Arbuckle also argues that the traditional cranber ry sauce from her newfound home state of Washington is the best original dish of the season.

Much farther east in the United States, Holliston, Mass., is the hometown of junior

biology major Aliya Marino.

Marino’s first and most orig inal holiday take is that stuffing is the best Thanksgiving food choice. Marino explained that the sharpest difference between the south’s dressing and northern stuffing is that stuffing is literally stuffed inside of the turkey. Dean and Duke explained that dress ing is more of a pan and side dish than a factor in the main entree.

The New England representa tive revealed that the dish is spe cial not just for its food content but also for the story of how the stuff ing was formed in her household.

“When I was younger, my dad would have his whole station set out and hand make everything. He’s always teaching me how to

make food: He’s taught me how to make pasta, how to cook a sau sage and what you use to cook it, and how to cook a turkey and all that,” Marino said. “So, I real ly just like the holidays because it’s a big bonding experience.”

Freshman biomedical engi neering major Emma Gottman is all too familiar with a family-ori ented Thanksgiving. The Quincy, Ill. native is firm in her love for the gratitude-filled holiday because it allows a chance to relive her Great Grandma’s presence through the Thanksgiving food she ce mented as a classic in her family.

“My favorite Thanksgiving food is my Great Grandma’s homemade egg noodles. She passed away a few years ago, but

Thanksgiving is approach ing, which means collard greens, turkey dressing and mashed potatoes are on the menu. While foods such as these are part and par cel of a traditional Southern thanksgiving, many interna tional students here at the university are not as famil iar with the fare in Missis sippi. Because this cuisine is new to them, they have a unique perspective to share.

Enrolling in a college in a different country means get ting accustomed to numerous social and cultural differenc es. One of those differences is what is on the dinner plate.

Sophomore Yersaiyn Yer kin, a mechanical engineer ing major who was born in Kazakhstan, talked about the culture behind his country’s food and how cuisine in his home country differs from the food in the United States.

“Kazakhstan was part of the Soviet Union in the past, so Russian culture influenced some foods in the country. (Ka

zakhstan’s) traditional foods have more simple ingredients. We use a lot of carrots, pota toes and onions, and we gen erally consume a lot of meat,” Yerkin said. “We don’t usually add a lot of flavors or ‘salsa’ to our national foods. I came to the United States last fall, and the foods were different from my country because we didn’t have as many flavors.”

While Thanksgiving is arguably the largest food tradition in the South, oth er countries have extensive food traditions, too. Sopho more Johnathan Dabel, an economics and public policy major, spent 11 years in Hai ti. He reflected on soup jou mou, a soup native to Hai ti that is typically made of potatoes, carrots and pasta.

“During the first three days or the first week of a new year, that’s all Haitians eat, non stop,” Dabel said. “The story goes back to when Haitians were free and became the first independent Black country. We decided to celebrate by creating this soup right here.”

Junior Muhammad Atta, a general business major, was born in Pakistan and lived

there for 17 years before com ing to the United States in 2019. He talked about biryani, a rice dish popular in Pakistan.

“Everyone who has vis ited Pakistan has always tried that,” Atta said. “It has chilies, coriander, cilan tro, you name it. There are more than 50 spices in it.”

Despite the differences in cuisines for many inter national students, Southern food leaves a delicious taste in their mouths. Fried chick en, mac and cheese and corn bread are favorites among the international students interviewed, and some foods even shared similarities with their native country’s fare.

“Kazakhstan was influ enced by Russian food cul ture, and Russian people really like porridge, which is similar to the oatmeal here,” Yerkin said. “We like to make similar types of ‘oatmeal.’ but we usually add milk and salt.”

Atta also revealed that several restaurants in his native country serve the same types of food one can find in the American South.

“We got a KFC, P. F. Chang’s, McDonald’s and oth

er restaurants,” Atta said. “In Pakistan, we have sweet pota to wedges, and it’s street food there. They sell it in winter specifically, and we add a lem on and some chili flakes on it.”

The students still hold an attachment to their native countries’ foods, and they continue to eat these foods while living in the United

we still make them every year,” Gottman said. “It’s something I learned to do from my Great Grandma, my Grandma and my Dad, so it’s just a really fun tra dition to eat egg noodles like we used to with Great Grandma. It’s a great way to remember her.”

Though egg noodles proba bly are not found on the menu at every household around this country, the dish of family to getherness and perfect nostalgia is prepared neatly in a cleverly placed bowl at all of these houses around the Thanksgiving season.

Whether in Hawaii, Mas sachusetts or Oxford’s back yard, the one thing all of these homes have in common is food bringing their families together.

States, although they have ac cepted and enjoy the large va riety of food available here in the South. From the perspec tive of these students, they will always hold an apprecia tion of their own native food, but it won’t stop them from enjoying a spoonful of ba nana pudding in Mississippi.

Camie Bianco and Liza Fruge get excit ed over plastic bags.

first, their excitement makes sense when you look at the full list of things that really make them jump for joy: packages of peanut butter crackers, cans of SpaghettiOs, squeeze pouch es of apple sauce and bags of Cutie brand tangerines.

inside a plastic bag and tie it tight, you get what Bianco and Fruge proudly call a Lovepack. On Friday, the Lovepack will be sent home with a K-12 child in the Oxford-Lafayette com munity who, otherwise, may not have food that weekend.

it organization that provides supplemental food packag

es to kids struggling with food insecurity in the Ox ford and Lafayette County school districts. The orga nization started when Mary Leary, president of Love packs, saw a similar program in another school district.

“[Leary] spoke to a friend of hers who was on the school board and asked if there was a problem with food inse curity inside of the Oxford School District,” Bianco, vice president of Lovepacks, said. “They did a little pi lot program in spring 2010 at Bramlett Elementary School. They had about 12 kids that they serviced and then realized that there are more children in our district that have food insecurities.”

After the initial pilot program, Bianco and oth ers were brought on board to help expand the organi zation, and Lovepacks has

been operating ever since. Now in its 12th year, Love packs serves more than 250 kids in the Oxford and Lafay ette County school districts.

In a community where food insecurity is seemingly invisi ble, the number of kids that receive Lovepacks can be sur prising, Bianco and Fruge said.

“We speak to different organizations, and they’re shocked when we tell them how many students that we know of that have food insecu rity,” Bianco said. “There’s no place in town where you would see what you stereotypically think, but there is a need, and it’s attached to many things. When you’re hungry, as a student, it’s hard to concen trate and show up for school.”

There is often another layer of invisibility due to the stigmas and judgment that students sometimes feel from receiving extra food, Fruge and Bianco said.

“We try to be really dis creet,” Bianco said. “(De livery of the Lovepack) de pends on whatever that student is comfortable with and not embarrassed by.”

Fruge, with a self-de scribed role as Bianco’s wing-man, said that the or ganization has experienced an approximate 75-person increase in the number of stu dents they service this year.

“We have more students in our district, and right now, food just costs more. Everything costs more. I think we have more people that need food for that reason,” Fruge said.

At every step of the way, from supply to delivery, Lovepacks relies on sup port from the community to keep the operation running.

On the supply end, Love packs relies on both monetary and direct food donations.

“The community has been super supportive and gen erous,” Bianco said. “The

city pantry gave us start-up seed money, and that’s how we bought our first loads of groceries. We place our or ders at Larson’s Cash Sav ers, a locally owned grocery store that has been working with us since the get-go.”

Although Lovepacks or ders groceries directly using monetary donations, there are many times when direct food donations have saved the day.

“It’s crazy to me how of ten we sit here panicked,” Fruge said. “One day, we were panicking and working it out and one day this lovely man who saw us in an article somewhere drove up with a trunk load of food. (Dona tions like this) always hap pen, time and time again.”

On the delivery end, Lovepacks works with many individuals and organiza tions that help to get the food to its final destination.

Aside from the hard-work ing network of parents that pick up and distribute food and Lovepacks on a weekto-week basis, Fruge and Bianco highlighted two im portant groups of packers.

The first group is students in the special education pro grams at Oxford Middle School and Oxford High School.

“We really couldn’t do it without them,” Bianco said.

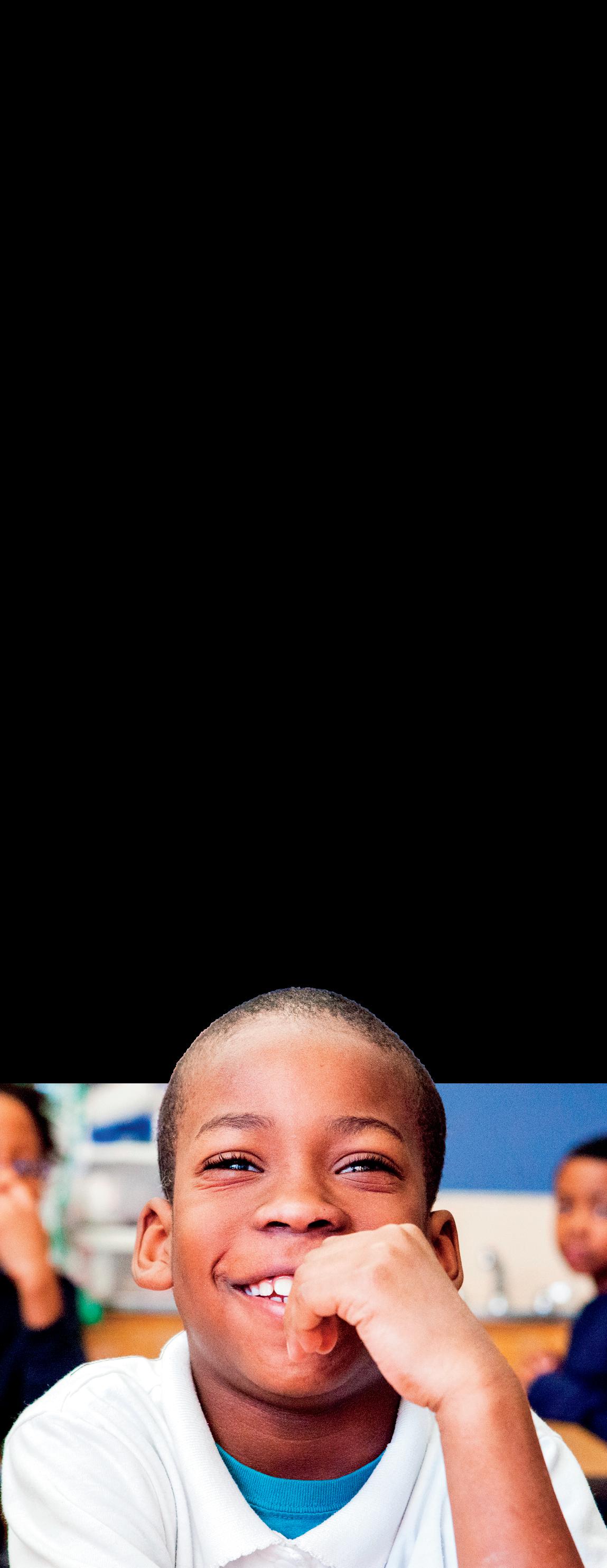

Kim McCarty, a special education teacher at Ox ford Middle School, said that helping with Lovepacks benefits not only students with food insecurity but also the students in her class.

“Our kids love it, and it teaches them working skills,” McCarty said. “When they get to the high school, they can get jobs so this helps them start training. This re ally helps the community, and they take pride in it.”

The second group is frater nity and sorority organizations on campus. Bianco and Fruge

rattled off a long list of orga nizations but noted Sigma Nu and Phi Delta Theta as some of the most recent contributors.

Daneel Konnar, a junior public policy and leadership major and member of Phi Delta Theta, talked about why his fraternity decid ed to work with Lovepacks.

“Our mission was to con nect our Phi Delt communi ty with the Oxford-Lafayette community. Even though we live in this great, beau tiful college town, there are still people who need our help,” Konnar said.

With the holidays coming up and food prices rising, Bi anco and Fruge highlighted how important it is for peo ple to consider donating to and supporting Lovepacks.

“We’re at Thanksgiving, and budget-wise we’re al most where we were at the end of the year last year,” Fruge said. “The biggest thing is either a financial do nation or food donation.”

To learn more about how and what items to do nate, individuals can vis it the Lovepacks website and social media accounts.

Bianco and Fruge also not ed how people can help sup port Lovepacks’ long-term growth. Bianco was enthusi astic about keeping current partnerships and establish ing new ones. Fruge noted the goal of having a dedicat ed Lovepacks pantry space.

In the end, Bianco went back to raising aware ness about food insecurity.

“The big thing is that the community continues to be aware that it’s still a problem and a growing problem,” he said. “It’s something that we can all help even if it’s just a lit tle bit. You know, Mother Te resa said if you can’t feed a mil lion people, at least feed one.”

On the Ole Miss campus, there are three separate dining halls: The Dish, located in the Luckyday Residential College, Rebel Market, in the quad, and the Grill at 1810, which con nects to the Ole Miss football team’s indoor practice facility.

Many students who reside in the LRC choose The Dish because of its convenience. Those who favor Rebel Market cite the central location as to why they dine there. The Grill at 1810, however, is special.

The Grill primarily serves as an athlete dining hall, but this does not mean it is exclu sively for athletes. The Grill is open to all Ole Miss students who have a meal plan, so it is typically packed with athletes and normal students alike.

In fact, it is interesting to see the effect the upcoming Thanksgiving break has had on the Grill and its occupan cy. People are rushing to get some amazing food before they have to go home for the break.

Because the Grill caters to athletes, there is a differ ent atmosphere when walking

in to eat. As people pass by Vaught-Hemingway Stadi um on their way to the Grill, whether they choose to drive or walk, there is a certain feeling that the meal they are about to eat will be unlike anything they have had on campus before.

It is hard to pinpoint what makes the food taste so good; maybe it is because they make it better for the athletes, or may be the environment itself helps the food taste phenomenal.

Every dining hall has a piz za station, but the Grill at 1810 must put some special kind of cheese or pepperoni on those pizzas because they run out in seconds. The grilled sec tion serves up pristine chick en and some perfectly made meatloaf. Not to mention, the service is second to none.

The workers are always smiling, they make conver sation and they always leave you with an “Enjoy your food.”

The Grill at 1810 is always packed with people from all over campus, which helps cre ate a laid-back atmosphere where someone can enjoy their food while potentially watch ing the football team practice.

That’s right — since the

Grill is directly connected to the indoor practice facility, people can see the Ole Miss football team practice. Es pecially now, since it is get

ting colder, the football team will utilize this field more than they have all season.

Once again, the Grill at 1810 is directly behind

Vaught-Hemingway Stadium. So before Ole Miss lets out for Thanksgiving break, go get some delicious grub from the best dining hall on campus.

Long lines occupy the Uni versity of Mississippi path ways as customers await their orders at the several food truck locations on cam pus. Hibachi, burritos and philly cheese steaks are only a few of the many options available to customers once lunch time comes around.

Despite the variety of foods and the apprecia tion many have for this form of food service, there is a common issue among students regarding prices.

One thing the food trucks have in common is a signifi cant difference in prices com pared to other restaurants on campus. A veggie burrito at

QDOBA is $8.29 with tax. A veggie burrito at Wiggly’s is $13.90 with tax, but students are still willing to pay the price

Public policy major and food truck customer Drew Moore had conflict ed thoughts on these prices.

Students have said that while the prices are higher, the portion sizes provided by these trucks are more plen tiful than most other food establishments on campus.

“I think it’s a good bit more expensive, but I don’t eat it often,” Moore said. “I’ll go to Qdoba and pay a pretty large amount too, but the hi bachi truck will usually give a bigger amount of food.”

Food truck employee Bra shonda Georgia compared her experience with these prices

to those of the Union. Geor gia said that chain restau rants on campus have some advantages over food trucks.

“They have more space and resources,” Georgia said. “We usually have to rely on ourselves. Our cheapest thing on the menu is $7 for fries.”

Georgia also mentioned that a further fluctuation in prices may depend on infla tion. Despite this, she re mains confident in the busi ness’s ability to maintain its success due to most custom ers’ appreciation for the qual ity and quantity of the food.

While students should cer tainly be given plenty of cheap options, there is a significant level of difficulty when small er businesses are forced to compete with bigger names.

Karlee’s Paleteria y Neveria is quickly growing in popularity after opening an authentic Mexican food truck serving fresh, slow cooked tacos, quesadillas and more.

Tucked between an auto shop and a gravel road on 266 County Road 101 in Oxford, pa trons driving into the parking lot are greeted with the smell of fresh tacos. You can stop by the food truck and sit outside to grab some quesabirria tacos and then walk through the front doors of Karlee’s ice cream and popsicle shop to snag a cup of tres leches homemade ice cream for dessert.

With the recent addition of the food truck parked right out side of Karlee’s, business has increased. Karlee’s owner Itzel Gonzalez says that the idea for the food truck stemmed from her realization that local, authentic Mexican food was difficult to find.

“I just felt like there are a lot of Mexican restaurants, but they’re more like Tex-Mex, so I felt like

there was still something missing that’s more Mexican, since I am Mexican,” Gonzalez said. “I want ed something more authentic.”

Karlee’s opened its doors just over a year ago.

Inspiration for the ice cream shop came from La Michoacana, a chain of ice cream parlors in Mex ico. Gonzalez says that when living in Mexico as a child, she and her family would visit La Michoac ana frequently, but after moving to the United States, the closest option for her was in Memphis.

Karlee’s, named after Gon zalez’s daughter, specializes in authentic Mexican recipe ice cream and popsicles, but also offers quesabirria tacos, que sadilla pizzas and sweet bread.

Gonzalez says that serv ing people outside of the Lati no community was unexpect ed, but she is happy that she is able to share her culture.

“At first I thought it was just going to be Hispanics or Latinos, but we have been having a lot of (people from) other backgrounds here, too,” Gonzalez said. “When

we have different people come, they always ask about the snacks other than just ice cream, and I always get excited and talk to them about it. I’m glad to share it.”

K.C. Kellum, manager at Chicory Market, enjoys having Kaylee’s next door. Most peo ple assume that the only things going on in Oxford are on the Square, Kellum said, so it is great to have another local busi ness on the north side of the city.

“It’s nice having some thing a little different. It’s not just another cheeseburger piz za joint,” Kellum said. “It’s neat to have a restaurant down in this area, especially one with some cultural significance to it.”

Nick Husbands, an Oxford lo cal, said that the quesabirria tacos and quesadilla pizza are his favor ites from the spot. He said that what he enjoys most about Kar lee’s is the food is more authen tic than other options in Oxford.

“I’ve been to Mexico a few times, and their food re minds me of Mexico,” Hus bands said. “I’ll try anything

on the menu. It all looks good.”

Ice cream is a staple at the parlor and soon will be made in-store. New ice cream and

“In many ways, the work of a critic is easy,” Anton Ego, the ominous food critic says in his review of the titular dish in “Ra tatouille”. “We risk very little, yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and themselves to our judgment.”

In the pursuit of artistic perfection (if there is any such thing), the creators inevitably finds themselves at a cross roads: the intersection between a stirring internal passion and the desire for external approval.

“Now shut up and eat your

garbage,” Remy’s loving but disapproving father, Django, bluntly says to him over a meal.

This inflection point is where 2007’s “Ratatouille” generates its unexpectedly poignant drama, as well as carves its uniquely endur ing legacy in the esteemed Pixar firmament, not to mention the greater cinematic firmament (as well as the Tik Tok firmament).

The internal and external are intrinsically tied in the he ro’s journey tale of the film’s protagonist, Remy, a rat whose highly developed sense of smell thrusts him into the wonders and spoils of the culinary world.

From toys coming alive to a corporate world populated by

monsters, Pixar has always oper ated in the most unlikely of sto rytelling terrain. Yet the famed animation studio nearly always manages to unearth the most universal depths of feeling, with “Ratatouille” standing as, per haps, the personal crown jewel of this long-standing sentiment.

“I can’t cook. But you can,” Lin guini, the amateur chef who forms the most improbable, yet lovable of tag-teams with Remy, says. Lin guini becomes the external chef, with Remy acting as ventriloquist, bringing his appetizing internal creations to life. This dynamic cul minates in the titular dish, which you can even make for yourself.

Despite these suspensions of disbelief, “Ratatouille” never loses its sense of candor. The rendering of the French culinary world, ex hibited in the Gusteau restaurant, lends a veracity that simply is not found in other films of its ilk.

It is within these specifici ties that “Ratatouille” finds its emotional grace notes and re mains the very reason it has endured on repeat for an en tire generation. A film that was

popsicle flavors can also be ex pected. More information on Karlee’s can be found on their Facebook and Instagram pages.

The titular dish comes to life from 2007’s “Ratatouille.”

once considered underrated, but is now considered nothing less than a cultural institution and an inspirational touchstone for the culinary and artistic worlds.

(swallowing his ego) by eloquent ly stating, “Not everyone can be come a great artist; but a great artist can come from anywhere.”

Ratatouille is avail able to watch on Disney+.

The chefs who keep the un dergraduate students involved in fraternity and sorority life well-fed each have a unique ex perience in terms of culinary be ginnings, the number of meals served and the type of clientele.

Nearly 39% of undergrad uates are a part of either fra ternity or sorority life. One large benefit to joining one of the nearly 35 Interfraternity Council and Panhellenic or ganizations the university has to offer is access to a common living space where students can have chapter meetings, social ize between classes and gather for meals cooked by profession al chefs throughout the day.

“My favorite memory of being a chef is just seeing the faces after people get their hands on the food that we cook and how they enjoy it,” Sigma Alpha Epsilon chef Lisa Wil son said. “And then having people come to you and com pliment you on what you do. That gives you a good feeling.”

Wilson has been working in the culinary industry since 2014. She has been a chef at three different houses at Ole Miss.

“I started cooking by chance, I guess. I started out in house keeping and when I got done

with my work, I would go to the kitchen and help,” Wilson said. “Sometimes I would just literally take over, and they just kind of let me so that’s pretty much how it started for me.”

Alpha Omicron Pi Chef Crysta Allen also had a somewhat unconventional start to her culinary career.

“Ever since I was 10 I want ed to be a cartoonist. Then, we got Food Network, and I was like, ‘Yes, this is what I want to do.’ I was obsessed with Emeril, Elton Brown and to a lesser extent Bobby Flay. I just love watching them do all the stuff. That’s like, that’s what I wanted to do,” Allen said.

However, Allen learned the hard way that the advice and opinions others had on her dream would hold her back if she took them to heart.

“When I got out of high school, I told everybody I want ed to be a chef and everybody was like, ‘Oh you want to be a cook’ and didn’t think I was good enough,” Allen said. So I got my degree in sociology, and I didn’t do anything with it. And then it wasn’t until I had my daughter in 2013 that I was like, ’You know what, I’m just going to do what I want and let her see me be happy doing what I like to do,’ so I went back to culinary school.”

While getting to pursue a

passion is a great benefit to being a chef, there are still struggles just like any tradi tional job. Cooking in such high volumes and under stressful conditions definitely brings some heat to the kitchen.

“It’s more of a personal thing but I guess just getting respect from people (is the greatest struggle),” Allen said. “Just to be honest, they see a young girl and a lot of ex perienced people don’t want to take orders from someone younger, but that’s probably the biggest struggle for me.”

Before she entered the AOII kitchen, Allen worked at the Beta Theta Pi Fraternity. Be ing chefs who have worked in both fraternity and soror ity kitchens, Wilson and Al len have observed one stark contrast between the men and women who eat their dishes.

“With the boys it’s sim ple. They just want potatoes, meat, and potatoes. The girls are more salads, pasta and stuff like that,” Wilson said.

While the men may have a more carb-and-proteincentric diet, there is still an art to crafting the menus each house has every week.

“We kind of rotate. We don’t want to have the same thing every day or every week, so we go by suggestions that you may want and work that into a

weekly menu,” Alpha Omicron Pi chef Lynne Roberts said.

Because meals are an inte gral part of each day’s schedule, the chefs and students have lots of opportunities to interact and form bonds with each other.

“After you see them every day for three or four days, you know what they like to eat and don’t like to eat and you can

look at them and you know if they feel good or if they don’t feel good,” Roberts said. “You just form a bond and a rela tionship with them. I just love everybody. I wouldn’t think of working anywhere else.”

• Former Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

• Practiced at his privately owned law firm for 45 consecutive years - located at the same place, being the Oxford Square, Downtown, Oxford, Mississippi.

• Taught the Mississippi DUI Law and 5 different Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure courses each and every semester at the University of Mississippi for 29 consecutive years.

• A member of the Chancellor’s Trust at the University of Mississippi since 1981.

• Former Municipal Prosecutor for the City of Oxford, Mississippi for over 6 years.

• Former Municipal Court Judge for the City of Oxford, Mississippi for 8 years.

• Former Vice President and President of the Lafayette County Bar Association; member of the Mississippi Bar Association, etc.

• Appointed by the Mississippi State Bar to the Mississippi Commission on Attorney Ethics and Attorney Violations of the Canon of Ethics and All Mandatory Rules concerning the Practice of Law. Occupied the positions of Vice Chairman and Chairman and served for 18 years.

• A Founding Member of the National College for DUI Defense conducted at Harvard Law School.

• Selected as one of the Top 50 DUI Attorneys in Mississippi by the National Advocacy for DUI Defense.

• Selected as one of the Top 10 Best Attorneys of Mississippi in for Client Satisfaction Award by the American Institute of DUI/DWI Attorneys.

• Selected as one of the Top 100 Trial Lawyers by the National Trial Lawyers Organization.

• Recipient of the DISTINGUISHED AWARD OF MERIT for 1989 from the Mississippi State Bar given to one Attorney in the State each year for outstanding contributions to the practice of law.

• Voted “Best Attorney in Oxford, Mississippi” in the Grove’s Choice Awards.

• Member of the American Association of Premier DUI Attorneys

• Member of the National League of Renowned Attorneys - Top 1%

• Awarded the United States Congressional Medal of Distinction by RNCC.

• Member of the American Jurist Institute - Top 10 DUI/DWI Attorney for Mississippi

• Member of the American Society of Legal Advocates - Top 100 Criminal Defense Lawyers in the State of Mississippi

• Selected by the Attorney and Practice Magazine as one of Mississippi’s Top 10 Attorneys, et cetera.

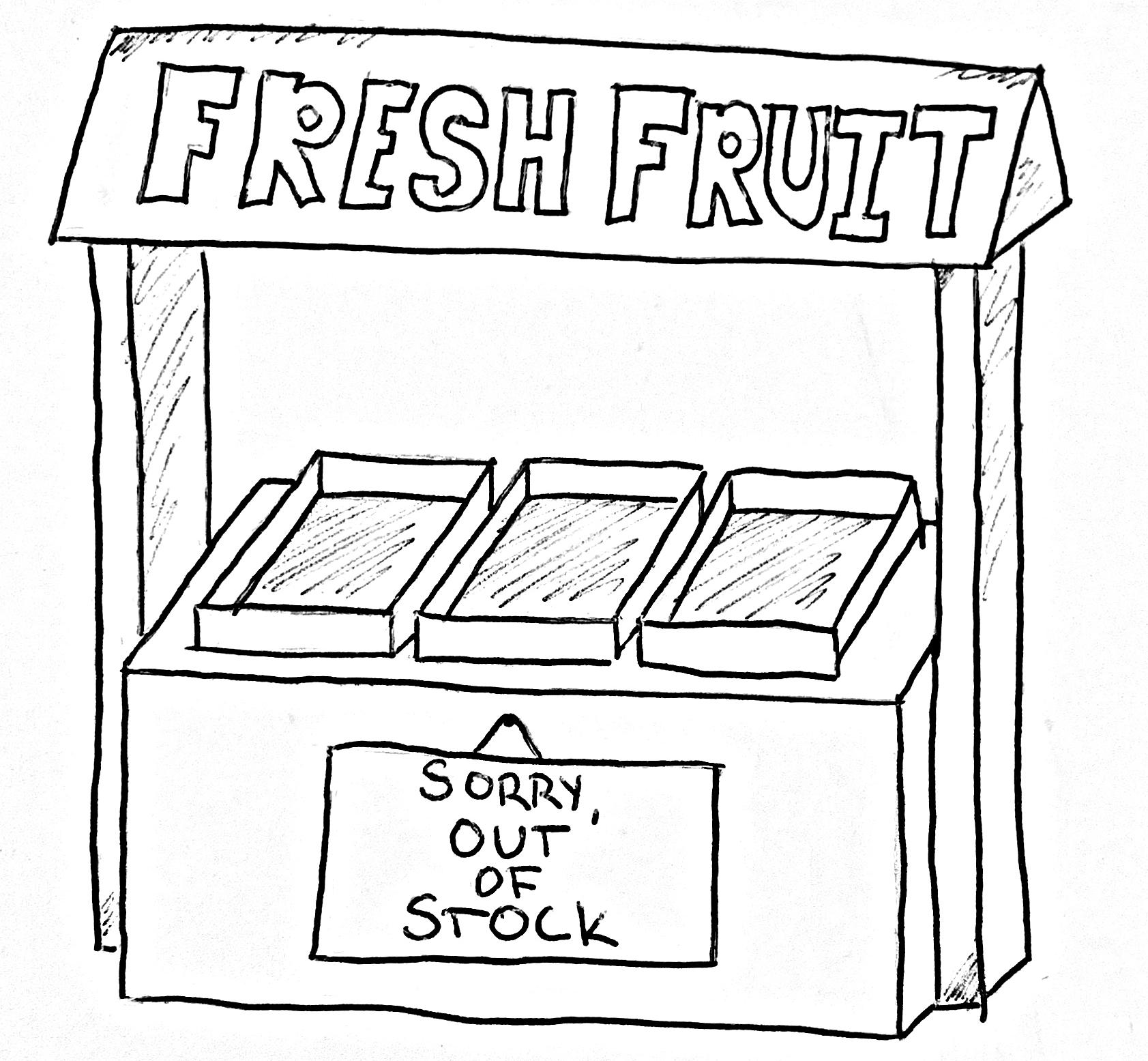

“Food desert” is a term used to describe areas where access to healthy and affordable food is lim ited. Rural and minority commu nities are disproportionately im pacted by food deserts, and that’s certainly the case in Mississippi.

Mississippi is the poorest state, with a poverty rate of 20.3%, and 50 out of the 82 counties are con sidered to be in persistent poverty.

But it’s also the hungriest state with 1 in 5 children going hungry.

In Mississippi, 15.3% of house holds are food insecure. Those rates are much higher in Mississippi’s rural areas than they are in urban areas due to the lack of resourc es to attain food. Female-headed households are also dispropor tionately impacted by food deserts.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits help provide some help to individuals experiencing food insecurity. In the state, more than 73% of SNAP benefit recipients have children.

There are different terms that can be used to describe commu nities who have limited access to healthy and affordable food, and in recent years, there has been a push by activists to use “food apartheid” instead of “food desert” to highlight how system ic racism and oppression led to limited access to healthy food.

Anne Cafer, director of the Center for Population Studies, as sistant professor of sociology and co-director of UM Community First Research Center for Well being and Creative Achievement, does not agree with this switch.

“I think the term apartheid has a very specific public connota tion—speaking very clearly of ra cial divides and specifically Black and white divides. I would worry that the use of apartheid would negate the nuances of race and racial disparities in food access and subsequently health access; it isn’t just a Black and white issue,” Cafer said. “(It also) negates the important differences in how poor food environment is experienced by folks from other types of demo graphic groups, rural versus urban for example or female-headed households. However I readily ad mit I don’t have a better phrase.”

According to the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70% of households eligible for SNAP benefits travel more than 30 miles to reach a supermarket. Traveling such distances can be expensive for low-income families who are already facing financial struggles.

The Oxford Community Mar ket is a non-profit organization committed to supporting local farmers and building a local food system that helps address food in security by making healthy, local food accessible to the community.

Market director Betsy Chap

man emphasized the impor tance of creating a community.

“Our goal is to build a farmers market community where every body feels welcome. We want our vendors and customers and volun teers and everything we do to re flect the demographics of our com munity at large,” Chapman said.

The Oxford Community Mar ket has multiple programs, which include accepting SNAP benefits, which they match up to $20, and participating in a Special Sup plemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

The Oxford Community Market also sends fresh pro duce to the Oxford Food Pantry.

“All of our outreach work is centered around providing ser vices for people who are most likely at risk of food insecurity and trying to reach their nutri tional needs,” Chapman said.

The market goes into communities facing food in security and helps make healthy, local food accessible.

On Nov. 14, the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement hosted their “Are You Ready?” dialogue series about “Food Insecurity in Our City.” It was a roundtable dis cussion on food insecurity and how it impacts the communi ty. Limited access to food can lead to poor health conditions.

“A lot of the food that we have access to that is inexpensive are

the unhealthy foods,” Victoria Zigmont, assistant professor of public health and health scienc es, said. “Fruits and vegetables are typically more expensive than the unhealthy foods, so people that are experiencing food inse curity have an easier time getting these unhealthy foods, and over time if you keep eating unhealthy foods you’re more likely to devel op different chronic diseases.”

The chronic diseases that can develop from food insecurity in clude obesity and hypertension. If someone is already experienc ing food insecurity, they may not

have access to preventive screen ings that can prevent heart attacks. There are multiple ways to combat food insecurity.

“There are many policy and practical approaches,” Cafer said. “For example, subsidizing the production of horticultur al products in the same way we do commodity crops. Develop ing robust rural transportation networks to get folks to grocery stores or supporting local grocers. These types of challenges require multiple stakeholders, multiple disciplines and lots of nuance.”

Whether Ole Miss students have a meal plan or rely solely on Flex Dollars, they depend on the dining services provided on campus to make sure they receive sustenance. Many stu dents have to strategize how much they eat in a day to make sure their currency lasts them the week, sometimes the entire semester. This strategizing has become a struggle in wake of ris ing food prices across campus.

Multiple factors cause pric es to rise, according to Joshua Hendrickson, chair of the uni versity’s economics department and an associate professor.

“Some of this has to do with supply chain factors related to the pandemic. Part of it is the war in Ukraine, and that is signifi cant because this is affecting en ergy prices,” Hendrickson said.

“So, it’s going to affect trans portation costs, which is going to increase the cost of getting food from one place to another.”

Sophomore english and classics major Grace Matting ly copes with rising food prices on campus by getting “small er portions.” Prices also have an impact on how healthy the meals are that she eats.

Sophomore accounting ma jor Madelyn Pozaric believes that prices are a cause for concern due to the pandem

ic and unemployment rates.

“I volunteer at Grove Grocery (the university’s food pantry, which works to alleviate hun ger on campus), and I’ve seen a pretty big rise in the number of students that are coming in,” Pozaric said. “From August un til now, there’s been a steady increase of people. I think that partially has to do with how much food costs have risen in the past couple of months.”

Pozaric explains that even though she’s a member of a sorority that provides meals for its members, she still uses a lot of her Flex dollars for small meals around campus.

Dr. Anne Cafer, direc tor of the Center for Popula

tion Studies and a sociology professor explained the effect expensive food can have on vulnerable students.

“I’ve worked with a cou ple of honors students who have done research on food insecurity on our campus, and what I can tell you from that data is that we see students that struggle to make food purchases, pay for housing or be able to pay for any kind of other service,” Cafer said.

Students often end up sac rificing a lot of their school lives and personal lives be cause they have to work.

“Students often have to forgo internship opportunities if they are unpaid because they have to

be compensated for their work in order to pay the cost of living,” Cafer said. “It’s also detrimental to the students because these in ternships would be really help ful in terms of getting a job or increasing their marketability when they leave the university.”

Food insecurity on campus can even contribute to extend ed graduation, as students miss classes, fail classes or have to drop out in different semesters to keep up with their work life.

Recent food inflation on campus sets many students up for failure, Cafer said.

“They have to deal with the health consequences of that, combined with reduced mental health status and reduced op portunities in their education.”

A

Josh Mallitz

ANNA GRACE BOWLING thedmsports@gmail.com

Mallitz said that although he does not have a set plan this Thanksgiving, he hopes to go to St. Louis, Mo., at some point over the holiday to spend time with his girlfriend and her family.

“If not, I’ll be spending it in Tampa with my family, and it will be more of a lowkey Thanksgiving,” he said.

Malitz enjoys all of the ste reotypical Thanksgiving foods such as turkey, honey baked ham, stuffing, green beans and mashed potatoes, but like anyone, he has his favorite.

the spring is going to look like for the Rebels in Swayze.

“I’m so excited for the spring,” Mallitz said. “We have a lot of young talent this year, also some great returning guys and a really good coaching staff.”

Mallitz also explained that the baseball locker room has been updated and transformed since the National Championship, consisting of banners, equip ment, posters and even murals.

Before coming to college, Mallitz typically would trav el with his extended family. But Mallitz said that since be ing in college, he’s had more traditional Thanksgivings.

“My favorite Thanksgiv ing food is definitely creamed corn. It’s my go-to, and I’m always going back for sec onds and thirds,” he said.

Obviously, Ole Miss base ball had an incredible sea son last year, and Mallitz is able to give insight into what

“This really helps bring up the morale of the team,” he said. “I can’t wait to be back in Swayze with a huge crowd watching us.”

Although Mallitz is unsure of which state he is going to be spending Thanksgiving in this year, he is happy to have a short, much-needed break from base ball to be able to eat creamed corn and spend valuable time with friends and family.

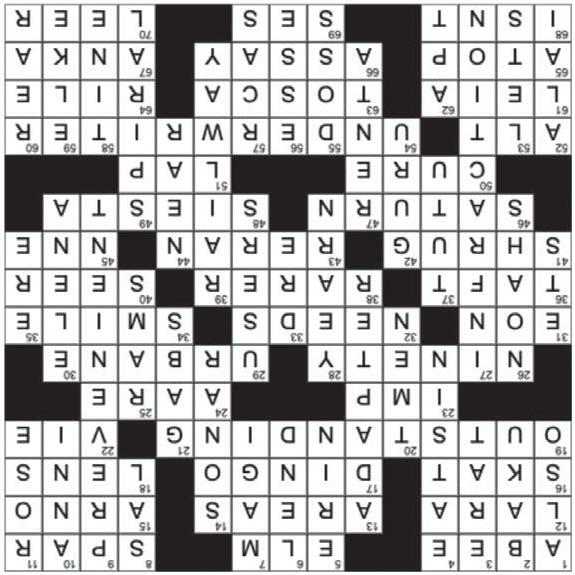

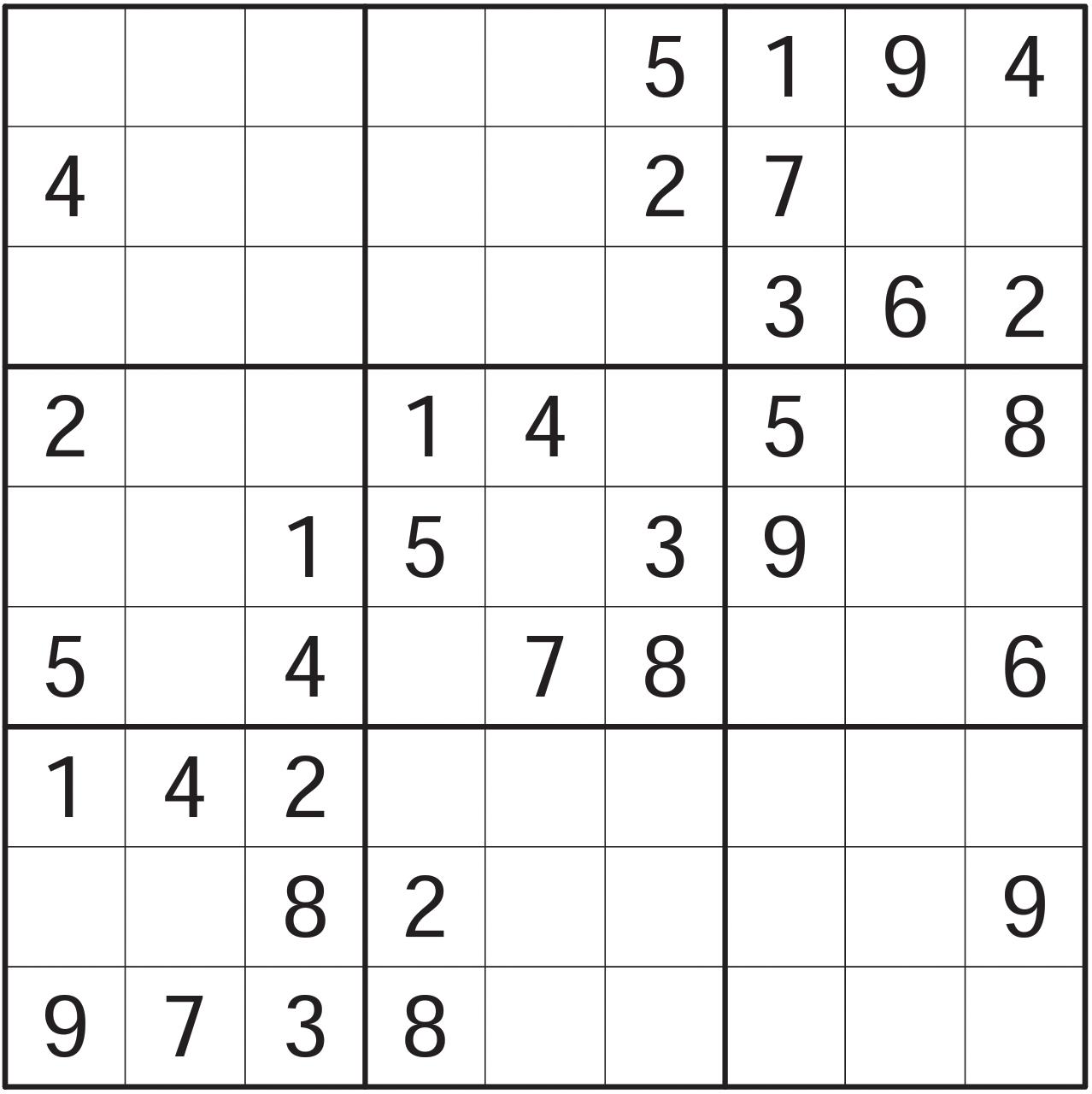

SUDOKU© Puzzles by KrazyDad HOW TO PLAY Complete the grid so that every row, column and 3x3 box contains the numbers 1 through 9 with no repeats. DIFFICULTY LEVEL

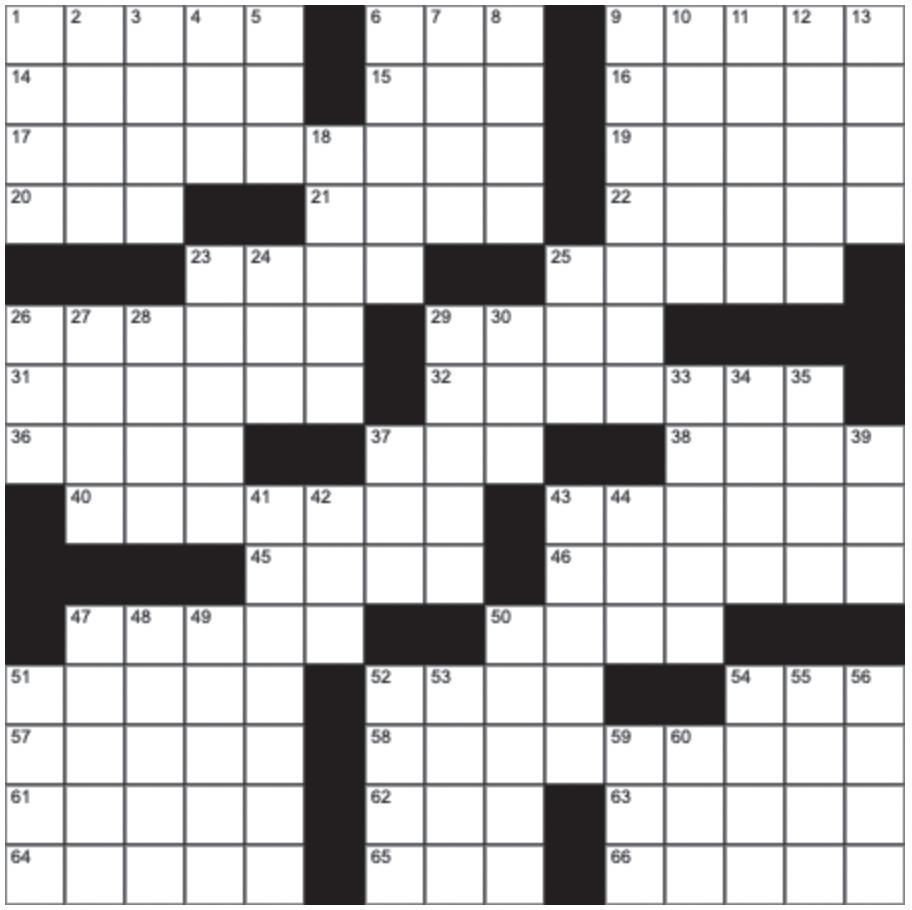

ACROSS 1- Hiding place; 6- T.G.I.F. part; 9- Like a ___ bricks; 14- Capital of Yemen; 15- Chiang ___-shek; 16- Declaim; 17- Made cheerful; 19- Nouveau ___; 20- Asian holiday; 21- Function; 22- Israel’s Shimon; 23- Chew on; 25- Conger catcher; 26- Goober; 29- Stream of air; 31- Entirely; 32- Swallow greedily; 36- Dutch cheese, wrapped in red wax; 37- D.C. VIP; 38- Dynamic beginning; 40- Scoffed; 43- Keep possession of; 45- Turner and others; 46- Disinclined; 47- Put to shame; 50- Mid-month times; 51- Growl angrily; 52- Actress Olin; 54- Samuel’s teacher; 57- Parts of hearts; 58- Elated; 61- Israeli desert region;

62- Back talk; 63- You ___ right!; 64- Designer Simpson; 65- High-pitched; 66- Warble;

35- Goddess and sister of Ares in Greek mythology; 37- Establish; 39- Half and half?; 41- Shackle; 42- College cheer; 43- Radiolocation; 44- 12/24 or 12/31; 47- Chipped in; 48- Vessel; 49- Shakespearean sprite; 50- Bumbling; 51- Yemen’s capital; Crossword puzzle provided by BestCrosswords.com (www.bestcrosswords.com). Used with permission.

52- “Damn Yankees” role; 53- Devil’s doing; 54- Gave the once-over; 55- ___-majesté; 56- Image of a deity; 59- Songbird; 60- Granada gold; NOVICE

It’s that time of the year again. The temperature and leaves are falling in unison. The semester has slowed to a stressful grind. Our long-awaited Thanksgiv ing break is finally at the doorstep. A needed week of rest to regenerate stu dents in preparation for the struggle that is finals week.

Thanksgiving is upon us. Thanksgiving functions as a pseudo-family reunion for many, which is why it’s my fa vorite holiday. You get to see your favorite cousins, have a laugh and watch the Detroit Lions attempt to win a foot ball game. A true spectacle. The Lion’s last five Thanks giving games could be used as an example of what not to do during a prime-time TV spot. Cowboys fans, you ar en’t safe, either. America’s

team has lost four of the five previous Thanksgiving out ings. This consistently plac es them in the biggest loser of Thanksgiving race, spot lighted by the perennial win ner, the guest bathroom.

Despite some truly dis turbing roots, Thanksgiving spreads a genuinely beautiful message. Take a day out of 365 days to be grateful. Express gratitude for those around you and the blessings you enjoy, no matter how bountiful or meager. It’s an important day for us to celebrate and observe in order to stay grounded and in remembrance of the traves ties the holiday is built upon.

That’s enough sermon, let’s talk about Thanksgiv ing’s biggest draw: the food.

Thanksgiving food is something that I cherish. Probably because many of the popular Thanksgiving dishes in the South are just straight-up soul food: mac and cheese, collard greens,

cornbread, candied yams, etc.

The listed dishes are all unfairly labeled side dishes. A silly byproduct of English colloquialism, because any body can tell you the side dishes are the true stars of Thanksgiving. Yes, turkey is essential to Thanksgiving dinner, but that’s because of tradition. Turkey is not the main character in the Thanksgiving cast. It can’t be. It goes against the prin ciple lesson of Thanksgiving.

Over the decades and cen turies, turkey ironically has assumed the spotlight on a holiday that preaches togeth erness and fellowship. There is a high chance that turkey isn’t the best meat available at any given Thanksgiving dinner. Ham has become a dual sport athlete, truly headlining Christmas dinner and popping up at Thanks giving celebrations nation wide. Barbecue is becoming a popular practice for the

holiday, too. This means that turkey could be matched up against ribs, chicken, pork chops, brisket AND ham.

Those are only the meats that are arguably better than turkey. The side dishes are, once again, superior. They play a symbolic role in the holiday, too. Assigning different dishes to visitors makes them more invested as parts to the whole celebration, playing on the “in this together, here for each other” nature of the holiday.

The bird has a lot to prove.

The correct pie ranking goes: pecan pie, sweet po tato pie, key lime pie, apple pie, chess pie then everything else. Cakes, cupcakes, cook ies, ice cream and so many more desserts are prepared for the holiday. It’s a disser vice, though. By the time des sert rolls around, everybody is stuffed. You’ll be lucky to find those who can stomach more than a slice or two of pie.

What’s my perfect Thanks

giving plate? Dressing and macaroni could occupy a third of the plate real-estate alone. Honestly, a good mac aroni dish and dressing pan carry so much weight on my Thanksgiving meal satisfac tion index. That cannot be overstated. Ham will usual ly be included in the firstround plate-building draft.

Don’t get me wrong, ham can be underwhelming. Partic ularly ham that is cut too thick, too salty or is not of the hon ey-ham variety. Those three traits in a ham could drasti cally tank it in my rankings.

Rounding out the first plate is candied yams and col lard greens and a dinner roll.

Proudly, my plate is not in compliance with the food triangle. Low vibrational plates only this Thanksgiving.

Justice Rose is the opin ion editor. He is a sopho more majoring in journal ism from Madison, Miss.

Columns do not represent the views of The University of Mississippi or The Daily Mississippian. The Daily Mississippian welcomes letters to the editor, which should be emailed to thedmopinion@gmail.com. Letters should be no longer than 300 words. They may be edited for clarity, brevity and libel. Third-party letters and those with pseudonyms or no name will not be published. Letters are limited to one per individual per month. Letters should include contact information, including relationship to the university, if applicable.