5 minute read

sacral landscape krajina duchovní

Sacral landscape

30

Advertisement

2

32

Since the beginning of human settlement, man has tended to adjust his surroundings. A type of landscape which is intentionally and harmoniously designed by man has been developing over time – a cultural landscape. It was made of various types of areas, e.g. meadows consisting of narrow agricultural fields, orchards, forests or ponds which were closely connected to villages and usually cultivated by peasants. Individual villages were connected by a linear hierarchized network of routes which made the landscape easy to pass through. Intentionally designed alleys planted across these routes provided peasants with the potential for refreshment and a little rest in the shade. These compound networks of routes were complemented by key compositional elements – landscape points-of-interest in the form of wayside shrines, calvaries or chapels which were erected on significant and memorable places or locations where specific events took place.

sacral landscape These wayside shrines, calvaries or chapels were sometimes newly erected on a place commemorating even older traditions or pagan rituals, so that newly emerging religions could physically subdue the old one just by adding a piece of architecture on a specific location. Historically, the same conditional principle was also applied in terms of celebrating significant holidays. [1] Newly emerged religion has made a place of ritual to physically change its form even if it naturally served well in the past. The landscape was not only a place of utility and a source of livelihood, but also a place allowing a deep spiritual experience of rural community. According to the establishment of Christianity across our territory, we can call it a landscape liturgy [2], usually holding religious processions, Eucharistic events or pilgrimages. The landscape was also a place made for personal prayer or expressing wishes, regrets and appreciation of an individual.

33

34

The elements of sacral architecture did not only symbolize the connection with Vertical worshipping, but also determined the time and place of worship or contemplation. The period of counter-reformation, which was the response of the Catholic Church to the doctrine made by Martin Luther, was driven by an effort to prevent its splitting. The Jesuits played an important role during the pursuit of unity. The veneration of saints, including the practice of Marian devotions also served as a tool for Catholization. It was the Jesuits who made a huge effort to spread the awareness of John Nepomuk’s life, even overseas. [3] However, the subsequent Baroque period was essential for further rural landscaping. During this time, the landscape was generously formed by large scale sacral buildings, chateaus, gardens or even small sacral monuments and alleys, mainly thanks to the resources provided by prosperous families and religious leaders. The

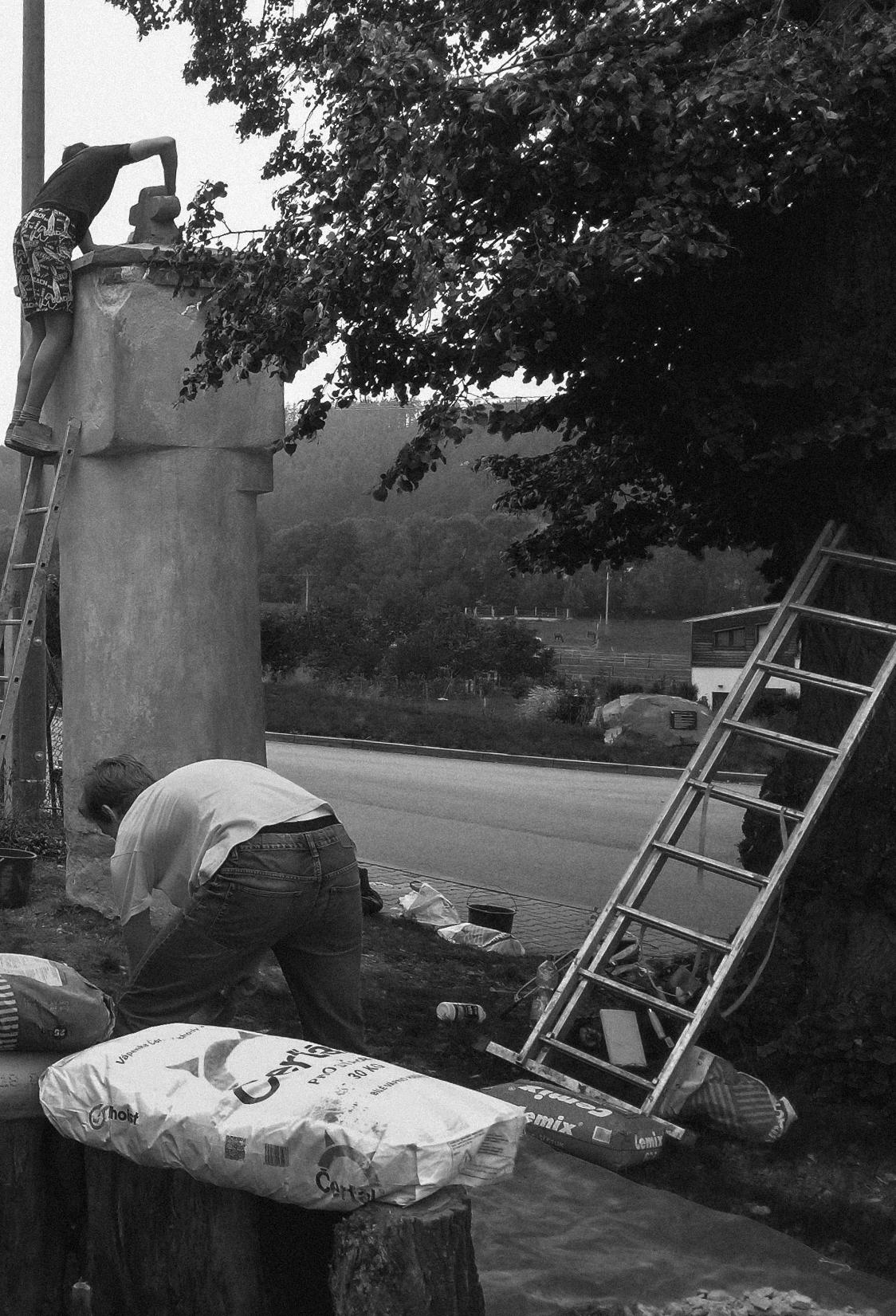

sacral landscape veneration of saints which was further established in terms of constructing more sacral architecture, lead to the chapels and wayside shrines being supplemented with statues of the Virgin Mary and statues of saints. During the 19th century, the amount of chapels, wayside shrines and especially calvaries which were erected across the landscape had increased. The calvaries were usually made of wood, but stone and iron alloys could be used for their construction as well. Wayside shrines and chapels were mostly made of bricks with lime plaster finish provided with niches in which statues of the saints were placed. [4] To be more specific, the construction of these elements of sacral architecture such as wayside shrines, calvaries or chapels has been a tradition dating back to the reign of King Bořivoj (9th century AD), who ordered at the request of Bishop Vojtěch that “at every gate of a Christian city a sign of the Passion of God was to be de-

35

36

picted or carved into a stone or timber and in every Christian village the same sign was to be depicted or carved into a stone or timber pillar. Since then, the tradition of building these elements of sacral architecture has been maintained in villages and public places.”[5] However, these structures also acted as educational elements for those who could not write or read. They were also built to commemorate the plague, poverty and to recall hope, faith and respect for the saints as representatives of Christian values. Those structures were usually found at crossroads which played an important role in life in the countryside.

sacral landscape

37

38

Již od počátku osídlování si člověk přizpůsoboval svoje okolí. Postupem času se tak vyvinul typ krajiny, která je záměrně komponovaná, harmonicky utvářená člověkem – krajina kulturní. Ta byla tvořena rozličnými plochami. Nalézaly se v ní plužiny – úzká pole s napojením na vesnici, jež jednotliví rolníci využívali k hospodaření či sady, lesy a rybníky. Vesnice pak byly spojovány liniemi – hierarchizovanou sítí cest, která krajinu činila průchozí. Stín a případné občerstvení putujícím poskytovaly stromořadí a aleje. Posledním kompozičním prvkem byl bod. Ten v podobě jednotlivých zastavení, křížů a kaplí upozorňoval na význačná místa nebo konkrétní události. Místa, na kterých byly stavěny kostely, kříže, kapličky či boží muka, navazovala na předchozí pohanské rituály a tradice. Často se tedy jednalo o přepis důležitých bodů v krajině novým náboženstvím. Stejný motiv se uplatňoval i v případě význačných svátků.[1] Tedy rituál nebo místo,

krajina duchovní které přirozeně fungovalo, dostalo společně s přijetím nového náboženství i novou podobu. Krajina tak nejen nesla rozměr místa užitku, obživy, ale byla rovněž prostředím pro hluboký duchovní prožitek celé komunity. S ohledem na rozvoj křesťanství na našem území můžeme mluvit o liturgii v krajině. [2] Konala se v ní náboženská procesí, výstavy nejsvětější svátosti, poutě. Krajina byla ale také místem osobní modlitby, vyjádření přání, lítosti nebo díku jednotlivce. Onu spojnici s vertikálou symbolizovala právě sakrální architektura, která uvozovala čas zastavení, usebrání a modlitby. Období protireformace, které bylo odpovědí katolické církve na učení Martina Luthera, s sebou neslo snahu zabránit rozkolu církve. Významnou roli ve snahách o jednotu hráli jezuité. Jako nástroj katolizace sloužil rovněž kult světců včetně kultu mariánského. Právě jezuité se zasadili o rozšíření povědomí o životě Jana Nepomuckého i do zámoří.[3]

39

40

41

42

Následné období baroka bylo pro formování krajiny zásadní. Díky prosperitě významných rodů a náboženských představitelů docházelo k velkorysému formování krajiny. Ta tak byla krajinou komponovaných zámků, zahrad, rozlehlých církevních staveb a alejí, ale i místem drobných sakrálních památek. V návaznosti na rozvíjející se kult světců byly kaple a boží muka doplňovány o sošky Panny Marie a sochy světců. 19. století pak přineslo další vlnu výstavby křížů a kapliček, zejména ze dřeva. Na stavbu křížů se rovněž používal kámen a slitiny železa. Boží muka a kapličky pak byly převážně zděné, nejčastěji s nikami s vápenným omítnutím, do nichž se umisťovaly sochy světců. [4] Konkrétně výstavba božích muk představuje tradici sahající až ke králi Bořivojovi (9. st. n. l.), který na žádost biskupa Vojtěcha rozkázal, aby „na každé bráně města křesťanského znamení umučení božího namalované neb vytesáno bylo a v každé vsi křesťanské aby totéž znamení na

krajina duchovní sloupě kamenném neb dřevěném postaveno bylo. Od té doby udržovala se památka stavění mouček na vsích a místech veřejných“.[5] Boží muka měla i edukační formu pro ty, kdo neuměli číst a psát. Stavěna byla na připomínku moru a bídy s cílem upomenout na naději, víru a úctu ke svatým jakožto vzorům křesťanských hodnot. Co se týče umístění božích muk, nejčastěji je najdeme na rozcestích, jež jsou důležitými místy v životě i v krajině.