MODERN HERITAGE UNDER PRESSURE KEEPING IT MODERN

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Edited by Aziza Chaouni with Dana Salama

Edited by Aziza Chaouni with Dana Salama

Copyright © 2023 by Aziza Chaouni

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form on by an electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

ISBN 0-313-17652-4

Published by the University of Toronto John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design

1 Spadina Crescent Toronto, ON M5S 2J5 Canada

Edited by Aziza Chaouni and Dana Salama.

With assistance from Hasan Hirji, Batoul Faour, and Kira James. Design: Dana Salama with assistance from Saaraa Prejmi. Cover Photography (front and back) by Andreea Muscurel.

Cover Design: Anna Toshkova

2

04

Aziza Chaouni with her grandmother Saida at the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Station.

This publication is dedicated to the memory of my father Fouad Chaouni.

I completed the acknowledgement and introduction of this publication while I was sitting by his side, in a hospital room in Rabat, Morocco, hoping that he will be out and safe soon. He passed away ten days later, on November 26th 2020.

Words fail me to express my infinite gratitude for his selfless love and generosity, for his enduring encouragements, and for his unique sense of humour that always lightened the toughest situations.

I miss him every day, and every day I meet someone whose life he positively touched. I will strive to continue his legacy.

To my mother Faiza Zemmouri, for her kindness, devotion, and love.

I would have never dared to go after my dreams without her selfless support and stimulating mind always by my side. Hence, my accomplishments are equally hers.

Aziza Chaouni, 2021

05

06

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication would not have been made possible without the ongoing support of the Keeping It Modern program director Antoine Wilmering, who has acted as a mentor throughout this journey. His team was also essential in making this publication possible.

In January 2019, the Keeping It Modern program at the Getty Foundation provided a generous grant to the John. H Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design to organize a workshop in the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath station on the conservation of modern heritage in the Global South. This grant further supported the process of compiling this publication.

I would like to thank the director of HRM Mr. Mohammed Karkari as well as the director of the Sidi Harazem hotel for hosting us with great warmth and professionalism. I would like to acknowledge the incredible logistical work of Daniels students Ted Marchant and Avery Clark, and Science-Po interns Alice Zaglia and Solene Pauly, who supervised the workshop organization in Morocco.

I would like to extend my gratitude to the authors of this publication, with whom we have collaborated over a year to finalize their papers.

At last, I would like to thank the amazing team of Daniels Faculty students and young intern architects who have been instrumental in assembling, designing and editing this publication: Dana Salama, Batoul Faour, Saaraa Premji, Kira James and Aidan Qualizza, as well as the graphic designer Anna Toshkova, who designed the cover of this publication.

07

08 CONTENTS PROLOGUE 10 INTRODUCTION 12 CONSERVING MODERN HERITAGE PLACES UNDER PRESSURE 32 THE ROLE OF CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLANS Sheridan Burke OSCAR NIEMEYER’S INTERNATIONAL AND PERMANENT FAIRGROUND OF LEBANON 58 CHALLENGES OF CONSERVING A UTOPIAN VISION Maya Hmeidan SIDI HARAZEM THERMAL BATH STATION 97 THE GENESIS OF A POST-COLONIAL MODERNIST LEISURE GROUND Aziza Chaouni THE KOSOVO NATIONAL LIBRARY 132 SHAPING NATIONAL IDENTITY WHILE PRESERVING A MODERN ICON Bekim Ramku THE METU FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE 166 CONSERVATION BY RAISING AWARENESS Ayşen Savaş

09 THE GANDHI BHAWAN 198 ASSESSING MODERN HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE AND DEVELOPING CONSERVATION POLICIES Shikha Jain THE PAROCHIAL CHURCH OF ATLÁNTIDA 236 A TRANSNATIONAL REHABILITATION Ciro Caraballo and Rodrigo Sáinz Lara AFTERWORD 270 Mohamed Elshahed IMAGE CREDITS 278 BIOGRAPHIES 286

PROLOGUE

BY SHERIDAN BURKE

All too often modern heritage places are under pressure, overlooked, and undervalued.

In February 2019, key members from the Order of Architects of Morocco, conservation groups, and architects working on the conservation of modern heritage from Egypt, Morocco, Lebanon, Algeria, Jordan, and Tunisia gathered in Sidi Harazem, Morocco, to discuss the issues facing the modern heritage in the Global South—specifically to examine how benchmark conservation planning processes could be adapted and used in their contexts.

The generous support of the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern (KIM) program brought participants to Sidi Harazem in Morocco at the invitation of Aziza Chaouni, engineer and architect, a Fez local and a global citizen. Aziza and her team of architects, engineers, researchers, and photographers were engaged in the task of preparing a Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for the extraordinary Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex designed by Casablanca-born modernist architect Jean-Francois Zevaco in 1960. Aziza Chaouni completed the CMP for Sidi Harazem in December 2019.

The ambition for the Sidi Harazem workshop was to raise awareness in the Global South, and specifically the MENA region about current methods of planning for the conservation of modern heritage. Participants were introduced to two key tools: the Conservation Management Plan process used by the Keeping It Modern program and the

international guidance charter Approaches for the Conservation of 20th-Century Cultural Heritage of ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on 20thCentury Heritage

The workshop showcased in-depth presentations of the work produced by KIM program grantees from Turkey, India, Kosovo, Uruguay, USA, Australia, Ghana, Lebanon, and Brazil. The case studies demonstrated how the same basic process of conservation management planning can be adapted into diverse cultural and regional contexts.

Being on-site at the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex provided the opportunity to see the site-specific issues first-hand, facilitating crossregional networking among participants during the workshop. Further site visits in Fes and Casablanca demonstrated the extraordinary inheritance of some of the twentieth-century planning and architectural heritage in Morocco.

Knowledge exchanges such as this workshop provide invaluable experiences and tools to support participants developing innovative and exemplary methods for assessing significance, an opportunity to develop policies with the potential for regional adaptation.

Many thanks are due to the workshop organizers, sponsors, speakers, and participants for sharing their knowledge and experience of modern heritage under pressure, demonstrating new pathways and opportunities for its proactive conservation.

Sheridan Burke ICOMOS ISC20C

11

Too many of the heritage places and sites of the twentiethcentury remain at risk. Although appreciation of mid-century modernism is increasing in some regions, the range of buildings, structures, cultural landscapes and industrial sites that are characteristic of the twentieth century are still threatened by a general lack of awareness and recognition. All too often they are pressured by redevelopment, unsympathetic change, or simply by neglect.¹

¹ ICOMOS ISC20C Approaches to the Conservation of Modern Cultural Heritage (The Madrid New Delhi Document) 2017.

12

INTRODUCTION

BY AZIZA CHAOUNI

My first memorable encounter with a modern, brutalist building dates from my childhood. As a young girl growing up in Fez, Morocco I often accompanied my late grandmother to the Thermal Bath in Sidi Harazem where she swam, drank from the hot spring water, and prayed to recover from her painful rheumatisms.

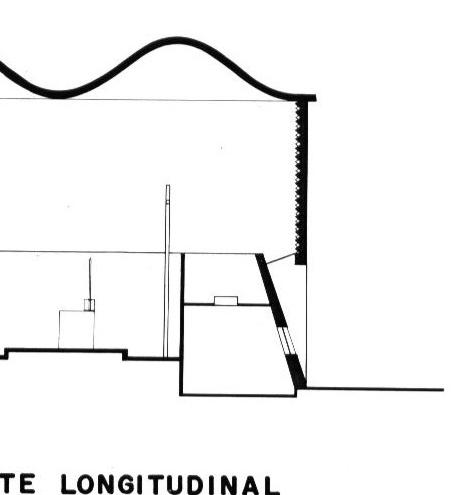

Designed in the 1960s by Jean-François Zevaco in an oasis located ten kilometres outside of Fez, the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex was a popular leisure, health, and spiritual destination attracting Moroccans from all over the country (figure 1).

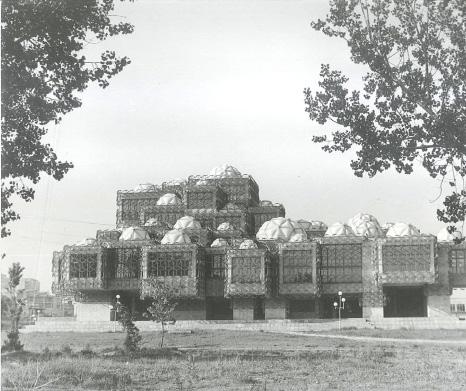

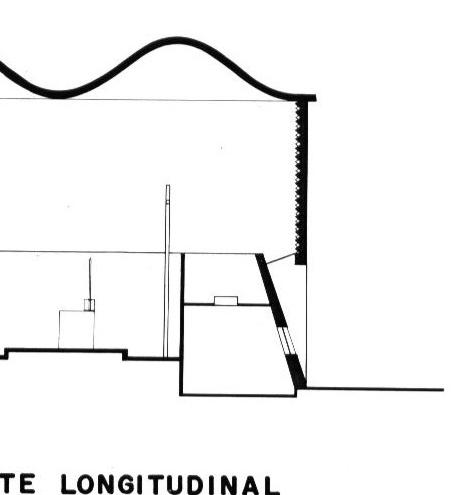

I recall my initial reaction—feeling fearful of the imposing behemoth which was unlike anything I had encountered before. I quickly became enthralled. Zevaco’s Thermal Bath existed beyond my wildest dreams. A palm tree oasis and concrete ‘city’ emerged abruptly from a landscape of cascading hills. The city was actually a tapestry filled with delicate filigree canopies, drinking fountains, blue mosaic-covered basins, constructed waterfalls, pools, labyrinthian pathways with pergolas covered in bougainvilleas, floating stairs suspended by thin cables, a market covered in concrete pyramids, and a building as large as a cargo ship raised on V-shaped columns (figure 3). It was a child’s paradise, a captivating adventureland that stood in stark contrast to the outside world I was accustomed to.

Zevaco’s Thermal Bath Complex not only represented new ways of building and making public spaces, but also offered a reinterpretation of Moroccan vernacular architecture—weaving water, gardens, courtyards and buildings in unexpected ways. It’s likely that the seeds of my interest in architecture

were planted during my visits to the Thermal Bath with my grandmother.

After starting my architectural education in 2000, I came to understand that the station’s heroic architecture fell within the corpus of brutalism, which Simon Phipps poetically describes as “an architecture of sensorial extremes,” offering “an extraordinary and unfamiliar experience to the visitor.”2 My nostalgia was tainted by the station’s decline, partial shut-down, and its abandoned architecture. Still, its aura remained unscathed. The station’s architecture shone brightly despite the addition of new buildings, the gradual emergence of informal markets, and the invasion of moss, rust, and nature.

My curiosity was sparked and I began studying the Thermal Station’s history. The stark lack of literature briefly halted my efforts. There was nothing written on Zevaco’s Thermal Bath Complex. Locals, the general public, and the professional architectural milieu in Morocco did not know of or appreciate the site and its exceptional architecture. By then, the Bath’s architect Jean-François Zevaco was old and ill, and after his passing in 2003 the archives of his work were quickly dispersed. This magical place which had captured my imagination as a child was dissipating before my eyes. Knowledge about the Bath’s genesis, construction, and architectural innovation was likely to follow the same fate.

Almost two decades later I received the support of Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern grant and embarked on developing a conservation management plan for Zevaco’s Thermal Bath Complex. The lack of awareness about the Bath’s architecture and Morocco’s twentieth-century

13

heritage from the post-colonial era was still staggering. This was offset by the emergence of few laudable initiatives led by NGOs such as MAMMA Group and L’Atelier de L’Observatoire.

Unfortunately the dismissal of modern heritage is a global phenomenon. Few modern buildings are included in the World Heritage List. Common threats to modern architecture include the obsolescence of modern buildings, urban development pressures, land speculation, the inadequacy of preservation laws, the scarcity of methodological approaches, and a systemic lack of public recognition. If efforts to preserve twentieth-century heritage can be traced to the listing of Gropius’ Bauhaus in 1963 and Brasilia in 1987, it was only in the 1990s that the conservation of modern heritage emerged as a distinct area of practice.3

Around the same time numerous local, national, and international organizations dedicated to safeguarding and conserving modern heritage were formed: chiefly DOCOMOMO International and its national chapters and ICOMOS 20th-Century Heritage Group.4 Their exemplary advocacy worked at the level of governments, the general public, and professionals towards the idea that modern heritage’s intrinsic qualities (technological, material, and cultural) are worth safeguarding. These advocacy groups have been instrumental at sharing and disseminating knowledge between countries such as sharing Heritage Alerts,5 approaches to conservation, awareness campaigns, conservation policy development and implementation, and technical expertise.

The Keeping It Modern (KIM) program launched by the Getty Foundation in 2014 is one such initiative,

14

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 AFRICA

WORLD HERITAGE LIST REFERRED TO UNESCO REGIONS

ARAB STATES

ASIA/ PACIFIC EUROPE/ NORTH AMERICA

LATIN AMERICA/ CARRIBEAN

Figure 1: World Heritage list entries per region, UNESCO.

promoting the preservation of modern heritage by offering grants and training workshops. The case studies presented in this publication are by several KIM grantees who have operated in the Global South.

If modern heritage is underrepresented in the World Heritage List, modern architecture from the Global South is even more of a scarcity (figure 2). At the turn of the millennium, UNESCO recognized the underrepresentation of sites from the Global South across all of the categories on the World Heritage List. ICOMOS was commissioned to assess these gaps.

The resulting 2004 advisory report The World Heritage List: Filling the Gaps - An Action Plan for the Future evaluated the World Heritage List based on regional provenance and timeline. It proposed the creation of a specific category for modern heritage - which was part of a lump category called 'special category'- and noted that Africa was missing altogether from the heritage in this category.6 Latin America, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia were also lagging far behind. In the aftermath of this report, UNESCO created a modern heritage category and committed to implementing a “global strategy for a representative, credible and balanced World Heritage List.”7

Still, the representation gap persisted. Cited causes include the disinterest of developing nations in heritage preservation which is not considered as an economic priority and the lack of importance given to heritage from the recent past. The institutional rejection of modern heritage in the Global South is intimately intertwined with not-so-distant colonial pasts, echoing issues of dependency and unequal

power relations between the center (Europe and North America) and the periphery (the Global South)—tensions which persist today. Gwendolyn Wright reminds us that we tend to “forget that modernism came into being in a world framed by colonialism where visions for improvement and innovation overlapped with and often caused brutal destruction.”8 The instrumentalization of modern architecture and urbanism as tools for exploitation and domination were carefully analyzed by Wright, Abu Lughod,9 and Rabinow10 in Morocco, Zeynep Celik in Algeria,11 Schlter in Douala,12 and Mia Fuller in Italian colonies.13

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, even modern heritage erected in post-colonial contexts in the Global South does not escape rejection by the general public and institutional bodies in those regions. This dismissal can be explained by the notion that buildings in the post-colonial era were often designed by Western architects in a seemingly rational, culturally neutral, and universalizing language mimicking the aesthetics of imperial power—and were thus perceived as a blatant extension of colonialism. It can also be argued that the choice of modernism’s architectural aesthetic was neither an imposition nor an unalloyed import in post-colonial nation-states. Modernism was purposefully chosen by nascent states after colonization to express technological progress and construct their new identities. The culturally specific manifestations of the Modern Movement that resulted were the product of transnational networks that were contingent, selective, and contested—appropriatly coined by anthropologist Christopher Rausch as ‘heritage assemblages.’14

15

16

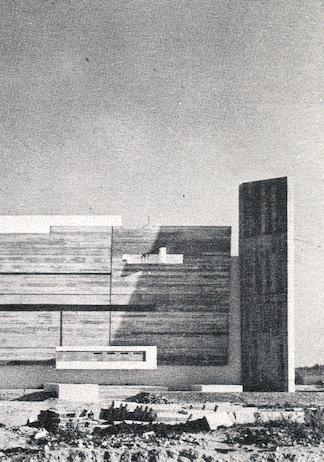

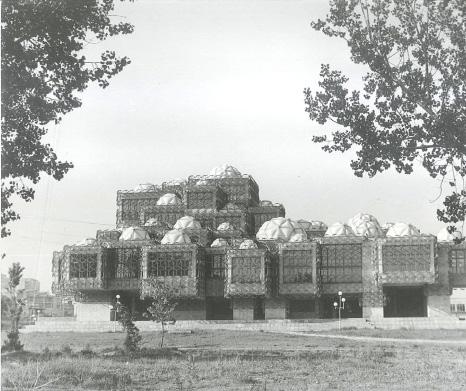

Figure 2: The hotel at the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Station, lifted on pilotis.

The widespread vilification of modern heritage in the Global South subsists, regardless of the era of its erection. By extension the act of preserving modern heritage is perceived as an imported, exogeneous endeavor, "often developed and consumed outside of the developing countries’ borders, a Western nostalgia far removed from the countries" pressing needs and a hindrance to their current development ambitions.

Paradoxically the buildings and infrastructures that were once instruments of modernization and political autonomy are today the remnants of a past that failed to deliver its promise of a utopian future.

The problematization of ‘modern heritage’ in the Global South demonstrates that a new framework is needed to carefully examine the shifting meanings of heritage from the recent past within the cultural, economic, social, and political landscapes of the near future. More critically, how can architects safeguard modern heritage buildings, landscapes, and infrastructures when literature applicable to their contexts is scarce? Where can information on tools and approaches relevant to the restoration of modern architecture in the Global South be found?

Over the past two decades, modernism from the periphery has known an accrued interest from scholars and curators – of note are Sarah Williams Goldhagen’s Anxious Modernisms, Duanfang Lu’s Third World Modernism, and the proceedings of the 2006 DOCOMOMO conference Other Modernisms–critiquing the exclusive and teleological histories of modernism centred on North America and Europe. Yet, there is limited scholarship on the approaches and tools needed for the conservation of modern heritage in the Global South. A common

17

presumption is that techniques successfully tested in the Global North can be successfully transferred to the Global South. However, the exacerbated tensions around modern heritage in developing nations require specific strategies suited to a context with limited financial resources, expertise, and where the recognition of modern heritage significance is lacking.

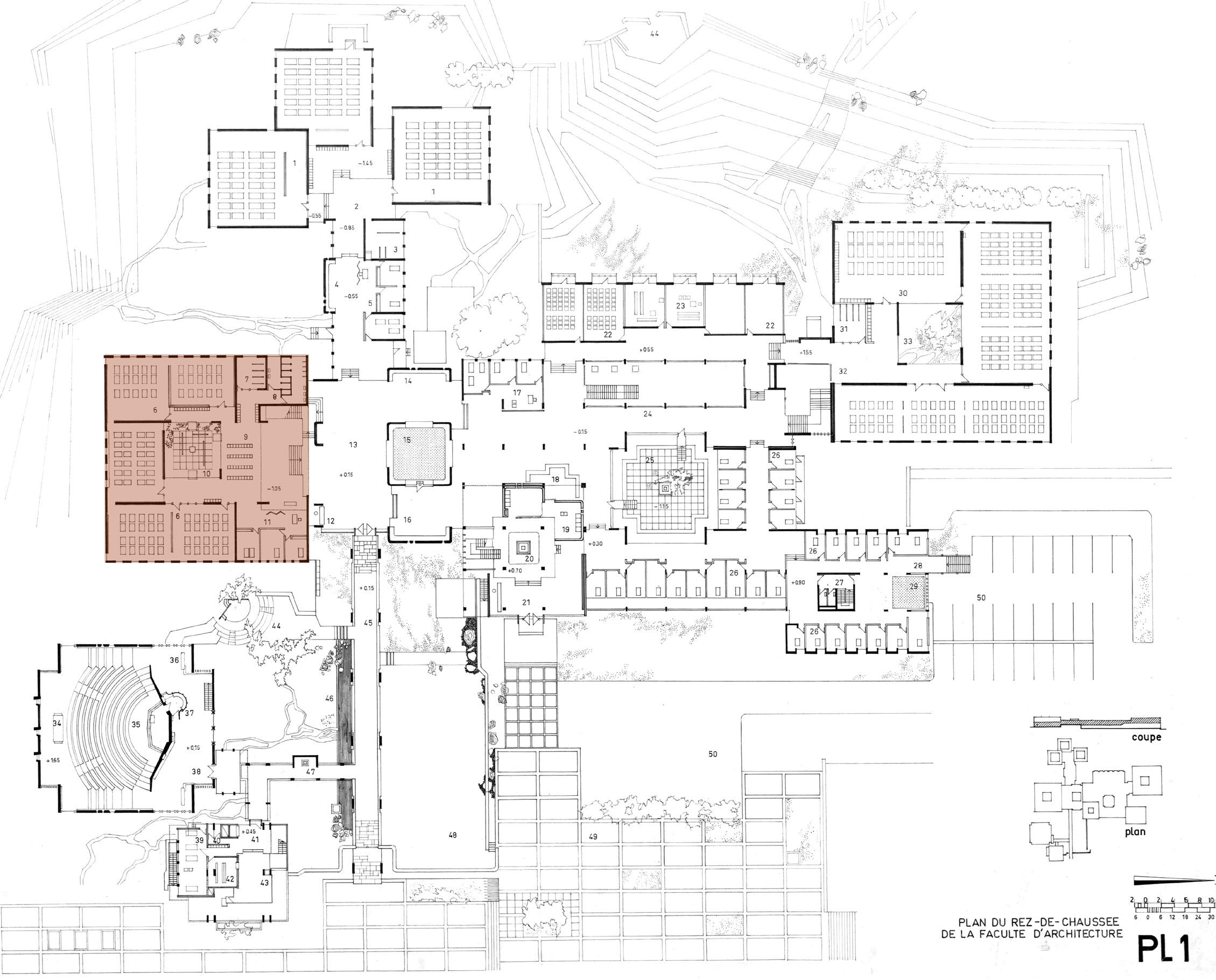

This publication aims to fill this gap by presenting seven case-studies from across the Global South, showcasing completed or in-progress conservation management plans (CMPs).15 The CMP is a roadmap that guides long-term maintenance and conservation policies based on the thorough investigation of the original design intentions, current building conditions, and the testing and analysis of modern materials.

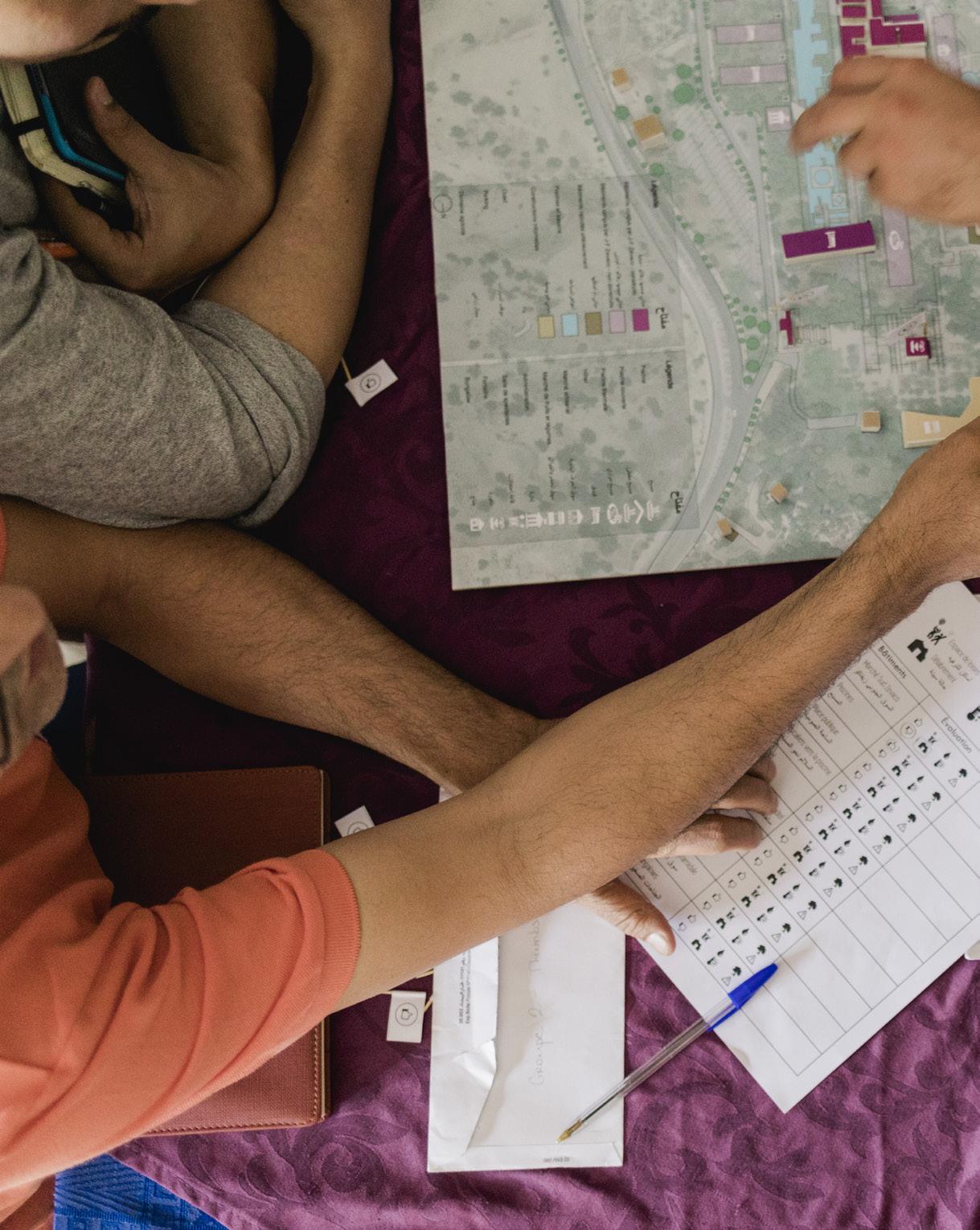

This publications’ case studies emerged from a seminar supported by the Getty Foundation Keeping It Modern (KIM) program titled Modern Heritage Under Pressure: Perspectives from the Global South, which I had the honour of organizing and hosting at Zevaco’s Thermal Bath Complex in February 2019. KIM is an international grant initiative by the Getty Foundation that promotes the safeguarding of heritage from the twentiethcentury. The seminar invited eight architects who were awarded the KIM grant to develop a CMP for modern heritage buildings or complexes of significance located in the Global South. The seminar in Sidi Harazem was a place to share methodologies towards the development of their Conservation Management Plans (CMPs) in Global South contexts.

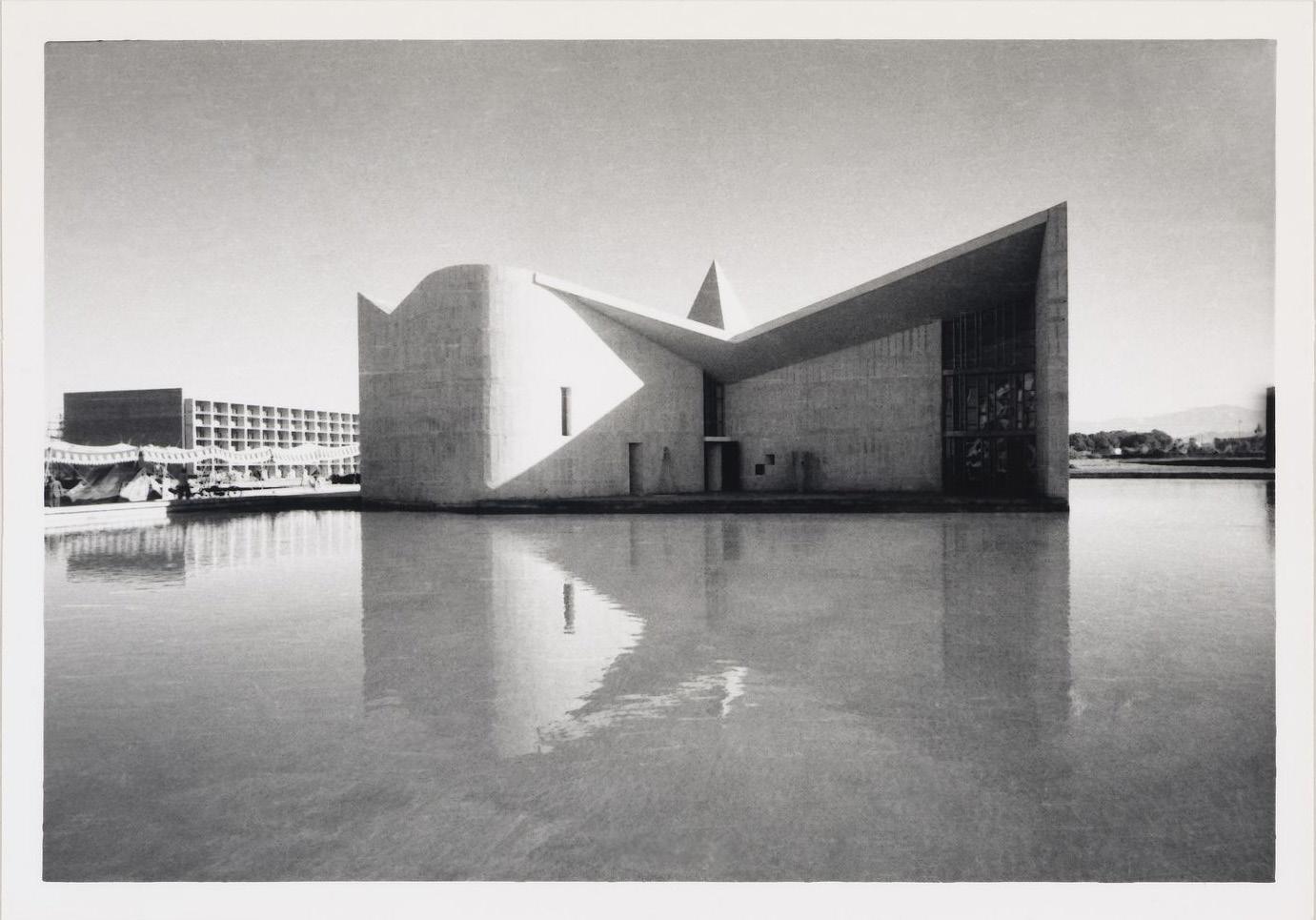

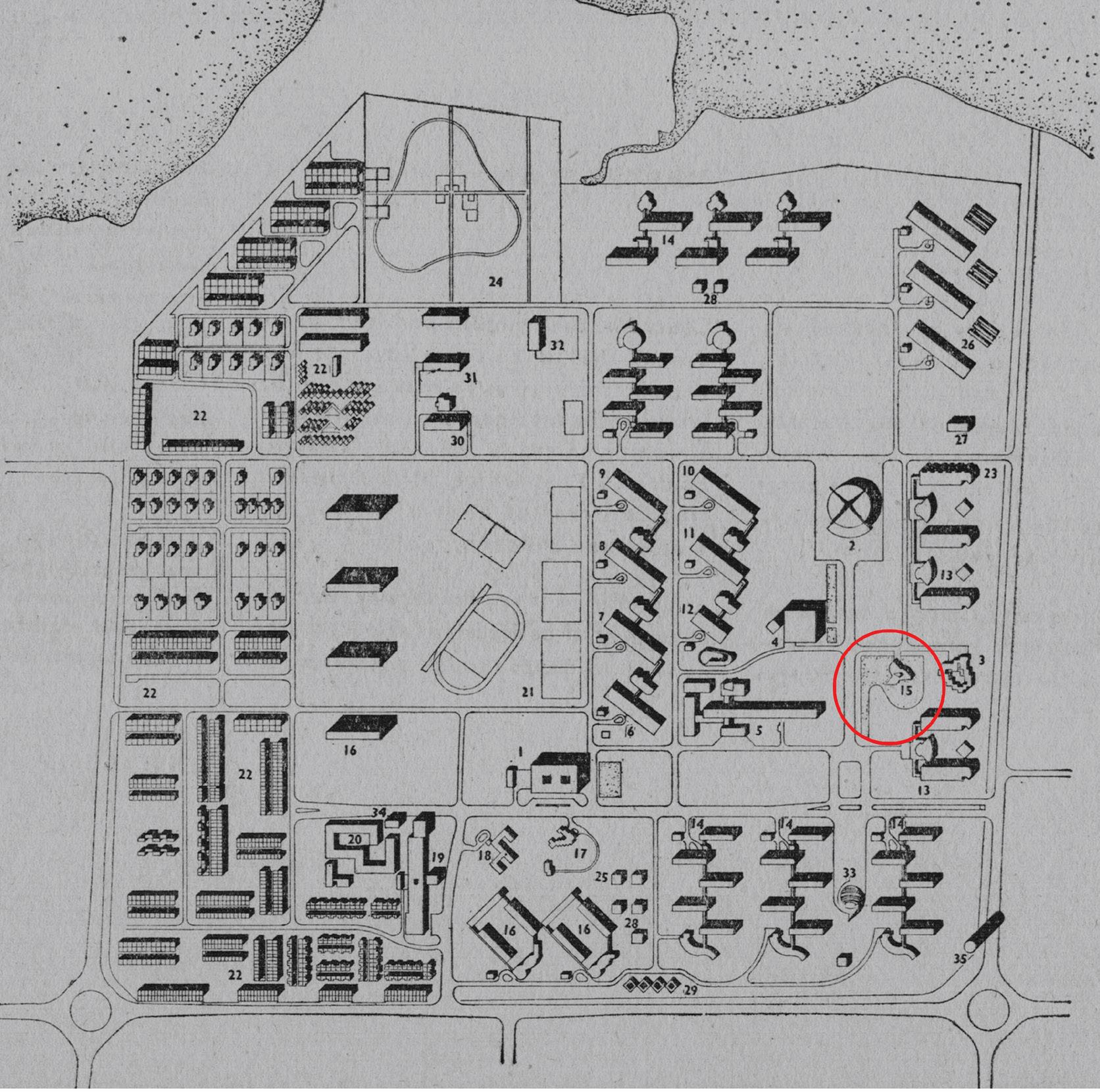

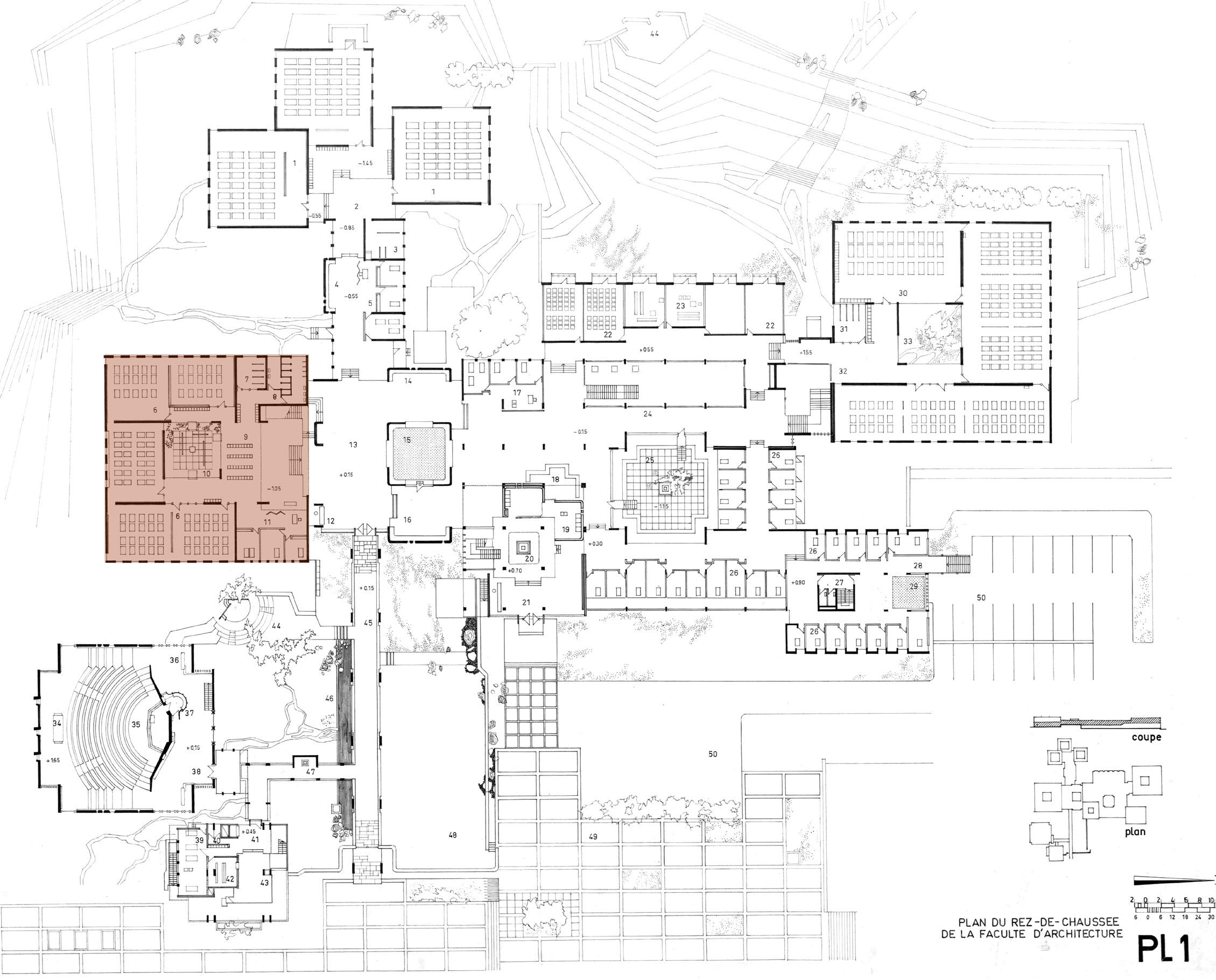

Seven of the eight cases studies presented at the seminar were chosen to be included in the publication: Niemeyer’s International and Permanent Fairground of Lebanon presented by Maya Hmeidan, Jean-Francois Zevaco’s Sidi Harazem (Morocco) by Aziza Chaouni, Andrija Mutnjaković’s National Library of Kosovo by Bekim Benku, Pierre Jeanneret’s Gandhi Bhawan (India) by Shikha Jain, Eladio Dieste’s Parochial Church of Atlántida (Uruguay) by Ciro Caraballo, and Altuğ and Behruz Çinici’s METU Faculty of Architecture (Turkey) by Ayşen Savaş. At the time of the seminar, four of the case studies had completed CMPs (National Library of Kosovo, Parochial Church of Atlántida, METU Faculty of Architecture and Gandhi Bhawan) one was in the middle of the CMP development process (Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex) and one was starting the process (International Fair Grounds of

18

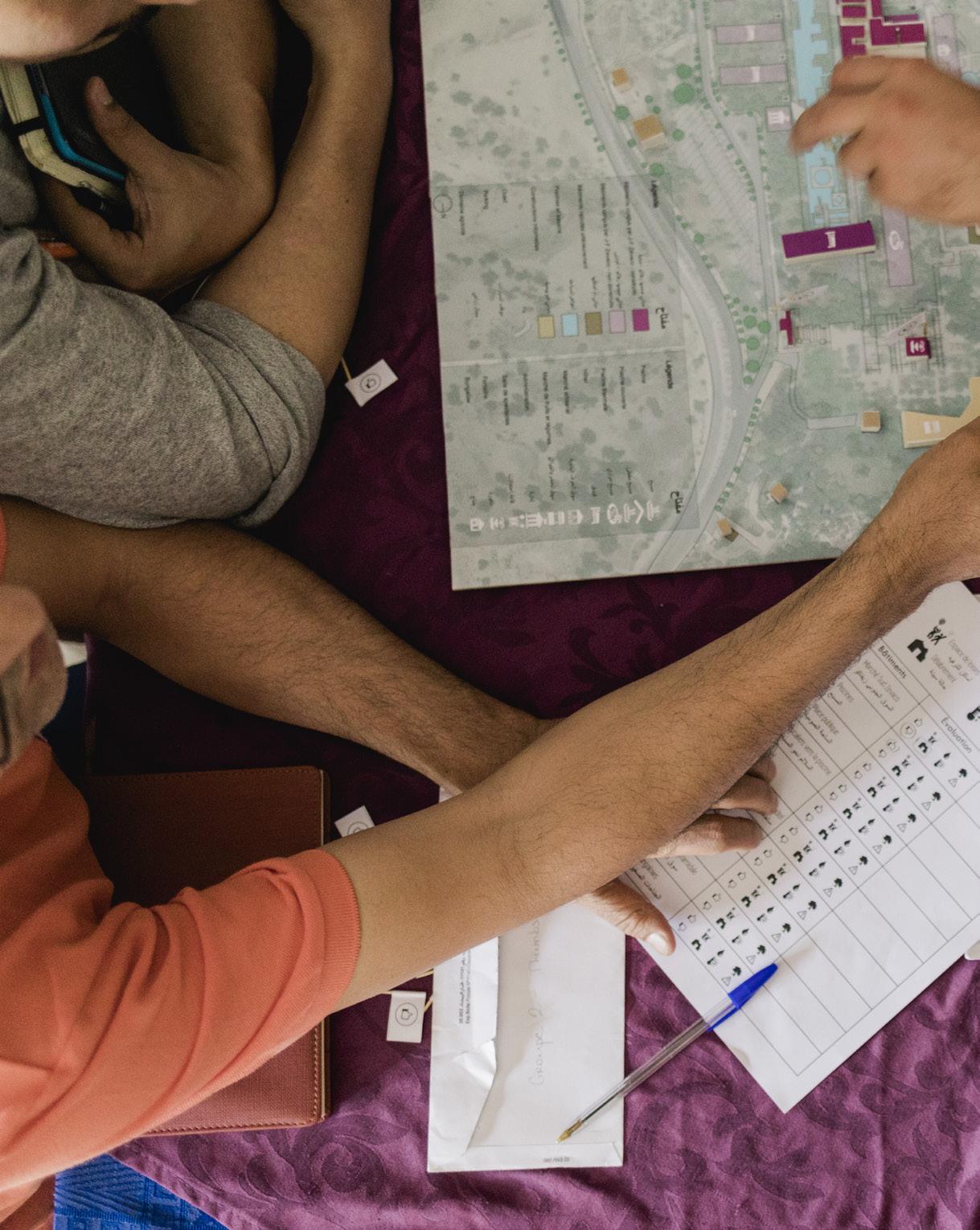

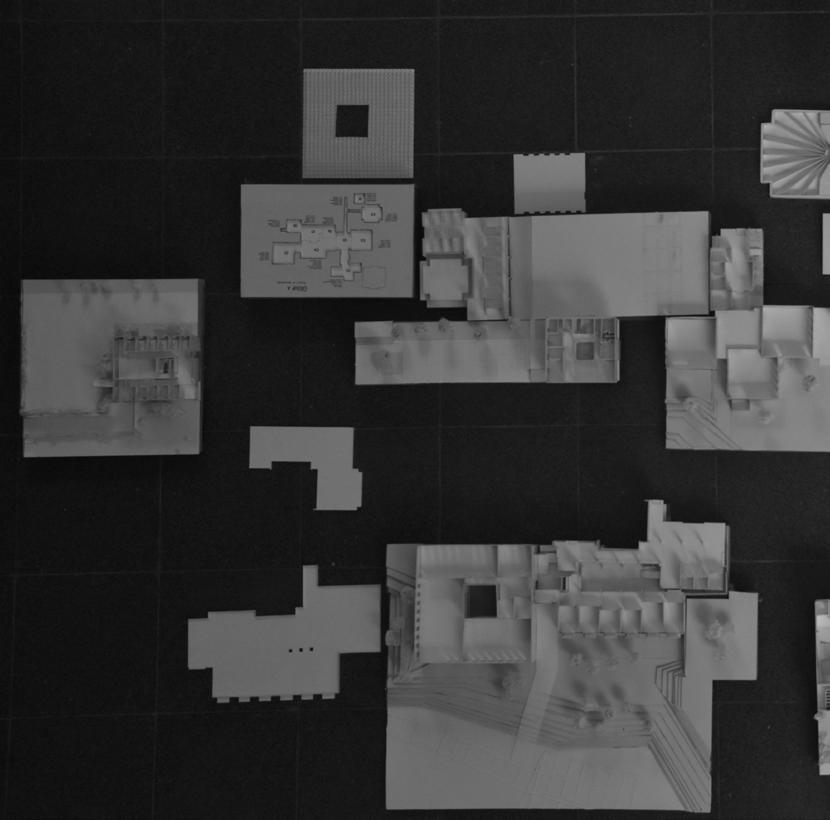

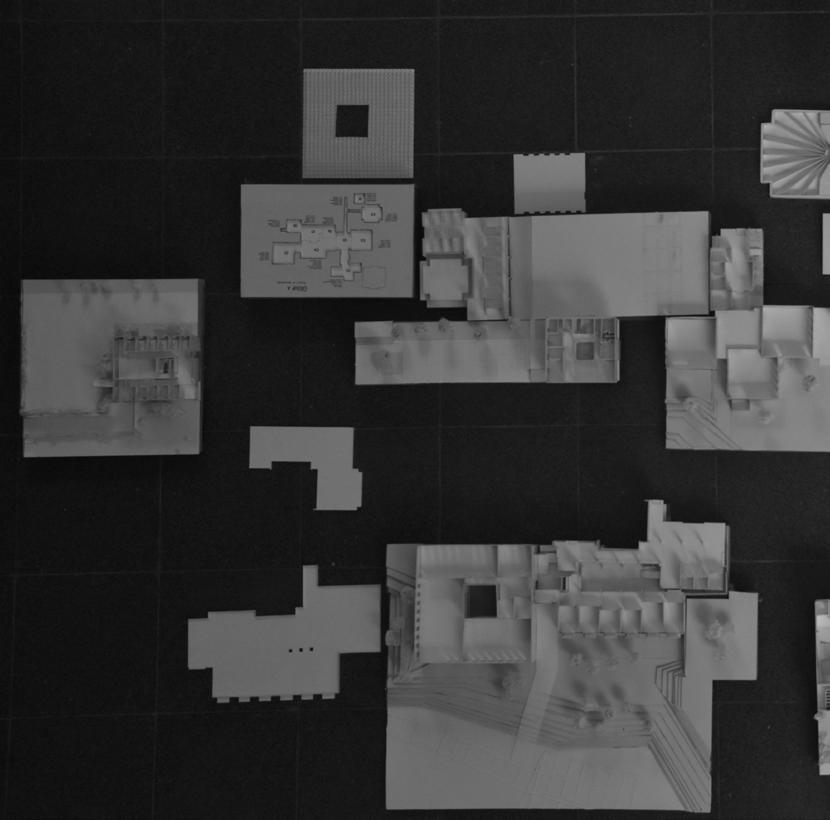

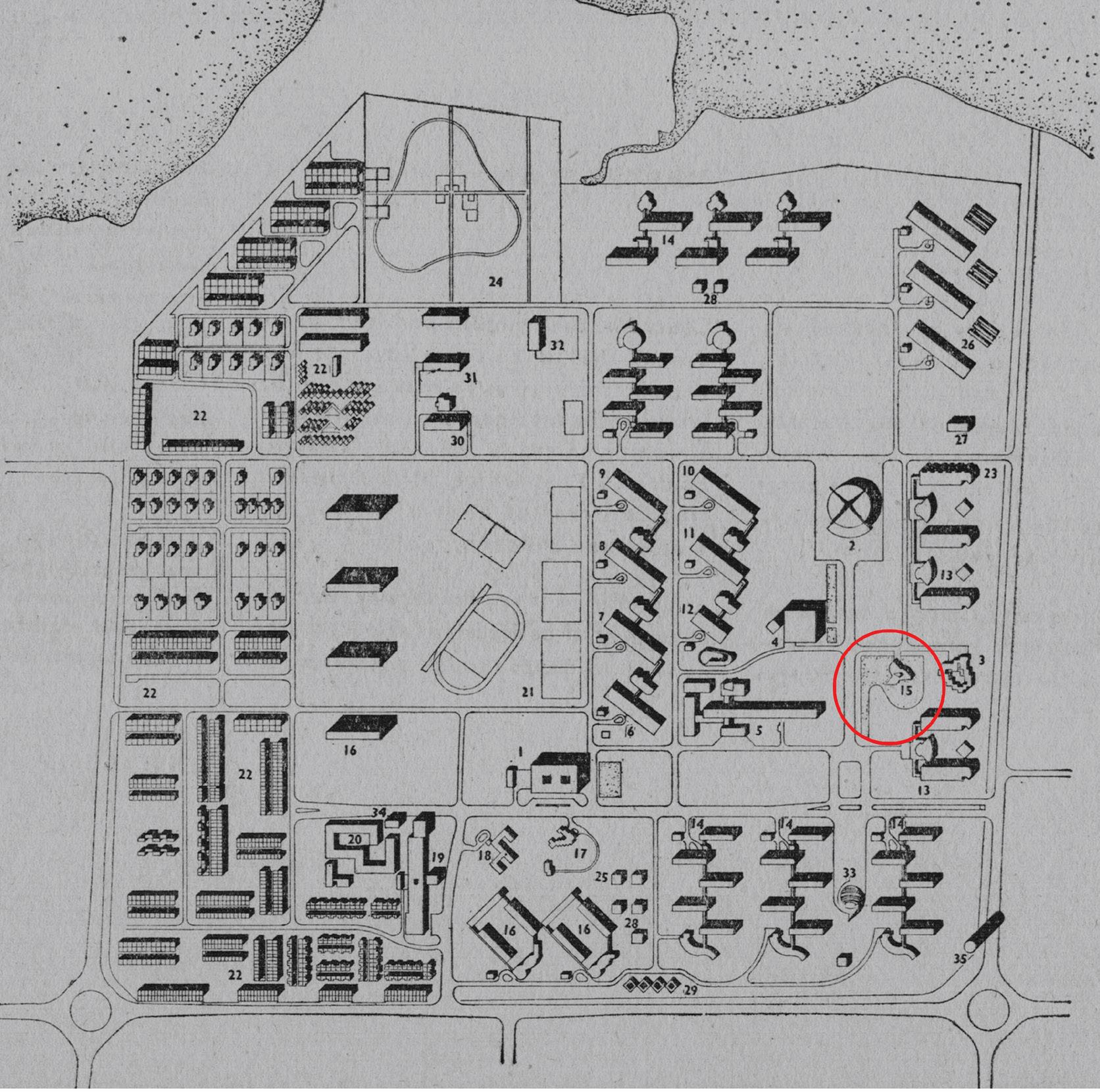

Figure 3: Model and questionnaire used during co-design workshops for the conservation masterplan of the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath.

Lebanon). Maya Hmeidan and Chaouni, with their CMPs in progress, focused on the data collection phase while the others presented an overall view of their completed CMPs, two choosing to focus on the phases they judged to be the most crucial: raising awareness for Savas and assessing the significance and developing policies for Jain. Beyond their location in the Global South, the seven selected case studies share several traits: (1) they were all built in the latter half of the twentiethcentury by post-colonial nation-states, (2) all seven case-studies are public buildings, (3) their proponents received a Keeping It Modern (KIM) grant, (4) their conservation strategy is driven by a conservation management plan (CMP) approach, and (5) the CMP effort is led by local leadership with roots in the site’s country or region. Both the

KIM grant and the CMP approach it promulgates enable modern heritage transnational networks or, in other terms, of global heritage assemblages. However neither the KIM grant requirements nor the CMP framework are prescriptive or topdown: while they set general goals to achieve a comprehensive conservation plan, the refinement of these goals and the implementation of corresponding methodologies can be adjusted by each team to account for contextual conditions and the specific needs of building owners. For example, the CMP of Lina Bo Bardi’s at-risk Museum focused on the building’s distinctive structure which was not yet fully understood, while the CMP for Zevaco’s Thermal Bath Complex and Niemeyer’s Fair developed conservation masterplan and typical rehabilitation solutions to address common problems plaguing the complexes and their structures.

The KIM grant is awarded to the building owner, creating conditions which promote conservation as a local, collaborative effort led by teams of local practitioners. This banalizes the practice of conservation , an important task in countries such as Morocco, India and Lebanon where modernism is still widely associated with colonialism and is therefore often dismissed.

Even though the case studies’ CMPs are unique, each loosely follows the methodology derived from the Burra Charter Process16 and refined by the Getty Foundation, which comprises seven main phases : 1) understand the place; 2) assess significance; 3) identify all factors and issues; 4) develop policy, 5) prepare a management plan, 6) implement the management plan, and 7) monitor the results and review the plan. These phases are

19

not intended to form a rigid framework, but rather, as Sheridan Burke states in her chapter outlining the CMP process, to inform “a simple logical development” that progresses from understanding the site, assessing significance and collecting data, to formulating and implementing policies to protect significance in the long term. The involvement of stakeholders to raise awareness, build consensus, and share the CMP process can be deployed throughout the aforementioned seven phases.

The analysis in the essays enclosed in this publication is done through the prism of the six of the seven aforementioned phases – given that, as of the publication date of this essay, the CMPs of the case studies are still in the process of being implemented - sheds light not only on a more refined framework for modern heritage conservation in the Global South, but also on leitmotifs about the challenges faced during each one of these phases.

1UNDERSTAND THE PLACE

Understanding the socio-political context in which a modern building or complex was commissioned, designed, and built forms the foundation of the CMPs used in all seven casestudies. Interestingly, all of the case studies in this publication were built in the 1960s and 1970s and share the same desire to express a modern national identity while incorporating vernacular techniques and aesthetics—a trait common to many modern buildings in the Global South.

In Lebanon, Morocco, and Kosovo national identities were formed as a counter-reaction to recent colonial pasts; which ended respectively in 1943 (Lebanon),

1956 (Morocco) , while the Yugoslav government granted Kosovo autonomous status as a region of Serbia in 1946 and as a province in 1973. These political conditions cannot be separated from the incorporation of regional specificities into modern public buildings built for newly-formed states.

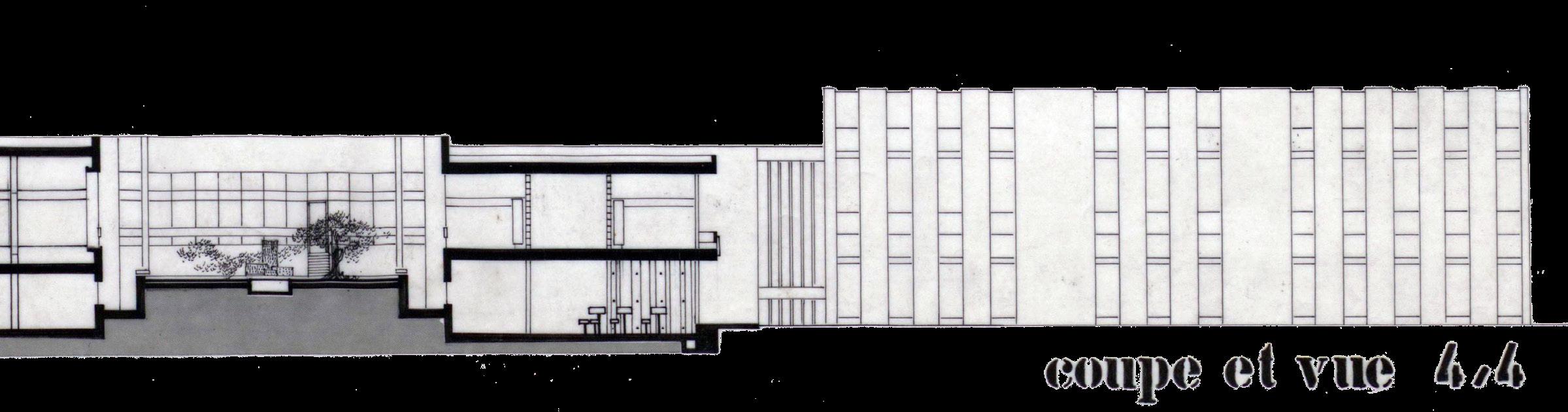

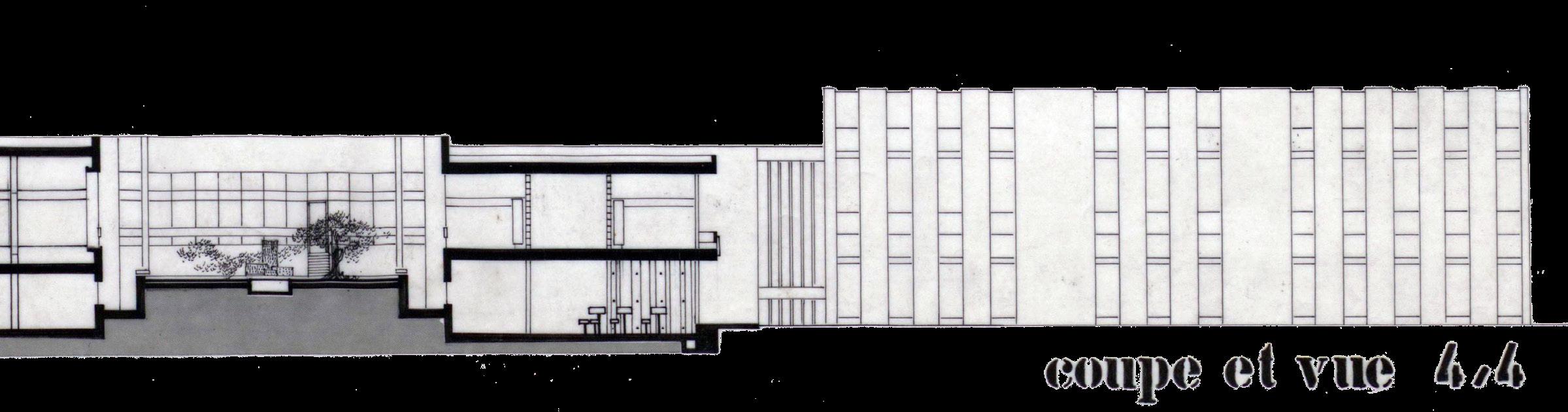

Turkey embraced a similar approach, a deliberate countermovement by young architectural vanguards against Hiltonism, a term coined by architectural critic Şevki Vanli to describe the uncritical deployment of the International Style in his country during the nineteen fifties.17 In the METU Faculty of Architecture Building, and in its campus at large, this sentiment was embodied through the integration of local materials and landscape features used to create microclimatic effects, thereby transforming the dry site into a lush environment.18

In Uruguay, Dieste opted for the use of concrete instead of brick to build ruled surfaces, at a time when his contemporaries (including Eero Saarinen and Félix Candela) opted for concrete. Dieste made the unusual choice to capitalize on the availability and affordability of a local material, and to ensure labourers possessed the expertise to complete the work. The use of brick not only made economic sense, but also allowed for his Atlantida Church to seamlessly insert itself within a long tradition of construction in Uruguay and Latin America.

2

ASSESS SIGNIFICANCE

Assessing the significance of a modern heritage building enables teams to not only prioritize key components for preservation within the CMP but also legitimizes the importance of safeguarding a work. The significance of modern

20

heritage can be assessed on many different levels: vis à vis its impact on the international, regional and local architectural arenas of its era; the political, cultural, and social symbols it embodies; its relationship to similar typologies; its structural, material, and programmatic innovations; the prominence of the architect, and others.

While assessing the significance of the buildings, teams faced a similar problem. Operating outside of the Western world, the original architects they were researching were unknown, and critical literature interpreting their work was scarce. While Oscar Niemeyer, Pierre Jeanneret, Behrouz and Altuğ Çinici, Lina Bo Bardi, and Eladio Dieste (even though the latter three had only recently received recognition) were widely studied, two other KIM grantees’ architects were barely known beyond the architectural circles in their countries—despite the originality and quality of their work.

While Zevaco’s work was unknown both locally and internationally, Mutnjaković received some local recognition. When the CMP for the National Library of Kosovo commenced in 2016, Mutnjakovic’s library had only a few academic references written in languages other than Serbo-Croatian.19 The most notable reference in English was Udo Kultermann’s 1993 book Architecture in Former Yugoslavia. 20 Later, the catalogue of the 2018 MOMA exhibition Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 19481980 introduced for the first time the remarkable modernist production of Socialist Yugoslavia to an international audience.

Similarly, Zevaco’s original body of work, which fully blossomed after Morocco’s independence in 1956, is sparsely documented. Moroccan post-colonial

architectural production was discussed mainly in architecture journals from the 1960s and 1970s, Udo Kultermann’s pivotal book New Architecture in Africa (1963),21 and more recently in a chapter in the SOS Brutalism22 publication that accompanied the eponymous exhibition.

The lack of local and international recognition for an architect practicing in the Global South renders the task of establishing his buildings’ significance arduous. Justifications have to be developed from the ground up based on thorough research which considers the political, economic, social, and cultural context surrounding the site’s construction. In addition, the overall body of work of the architects, their peers, and their contemporaries needs to be understood, even with the limited resources available.

The seven case studies display a wide range of significance values. For the Church of Atlantidá, its significance was embodied in its technical and constructive innovations that push the limits of concrete shell structures with an unprecedented economy of means and the creative approaches to daylighting. For the METU Faculty of Architecture, its multifaceted significance included its continuing role as a beacon for architectural education in Turkey, its material and technical innovation, its integration of landscape and artwork, and its setting in a modern campus first of its kind in the country. For the Gandhi Bhawan which was part of the Panjab University Campus, significance was carefully categorized. First, the building’s significance was assessed within three thematic processes of twentieth-century India: ‘National Identity,’ ‘Campus Building,’ and ‘Urban Architectural Ensemble’. Then, its cultural significance was established

21

22

Figure 4: The arid mountain landscape around the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Station as seen from Zevaco's complex.

through prisms of historic, aesthetic, architectural, and intercultural values.

3

IDENTIFY ALL FACTORS AND ISSUES

Collecting data on the history, evolution, and current state of a modern heritage building is necessary to fully grasp the context, physical attributes, and to provide a deeper understanding of the place.

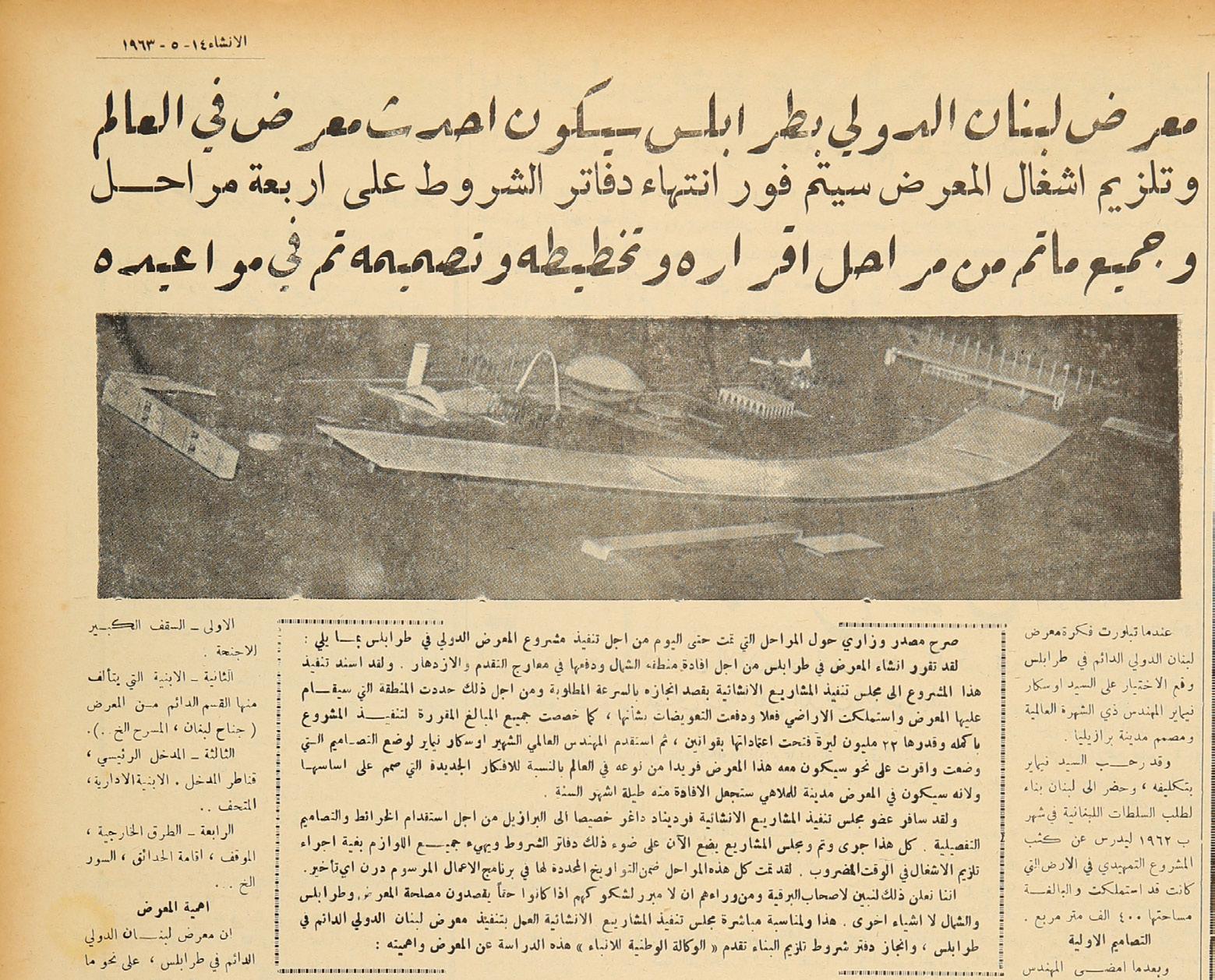

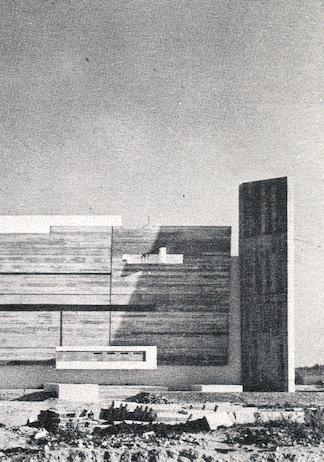

Teams meticulously gathered information from a wide array of sources including archival drawings, construction site reports, correspondence between the architect and other stakeholders, newspaper clippings, brochures, academic journals, publications, TV footage, videos, photos, oral histories, and site visits. Data gathering is particularly difficult in the Global South, where architectural archives are rarely institutionalized and are often spread between several parties and locations (often various countries). How can the intentions of the modernist architect be deciphered when archival information is missing? What if the design is partially realized, or if it has experienced alterations? In some cases such as Sidi Harazem or Neimeyer's International and Permanent Fairground of Lebanon where no full drawing sets could be retrieved, the CMP teams used a series of inventive tactics to offset data missing from the original designs. Sidi Harazem, for example, had original buildings and landscapes that had been obstructed by informal additions, and site elements that bore the marks of two poorly executed rehabilitation efforts. The task of determining original material was exceedingly difficult. The project team circumvented these challenges by relying on oral histories—

conducting a series of interviews with Zevaco’s colleagues, staff, family, as well as with visitors and staff of the Thermal Bath Complex. A social media campaign titled Sidi Harazem, Je Me Souviens was deployed to encourage the general public to submit images of the Thermal Bath Complex and share their memories of the place. All of the information was assembled and allowed the team to draw a full masterplan of the site (which did not exist as a document), and to rediscover site elements that had been lost through previous rehabilitations.

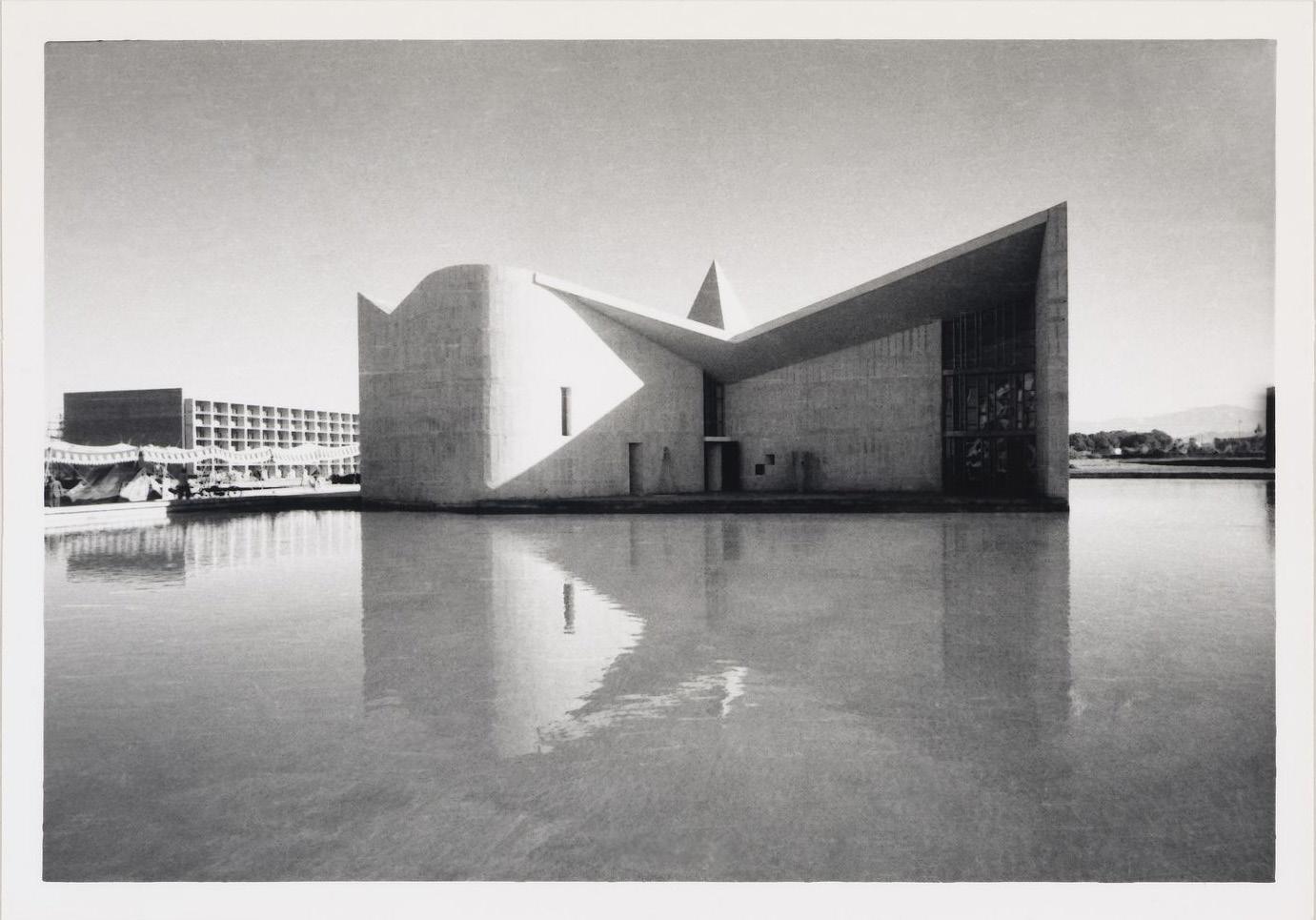

Similarly, Niemeyer’s Fair in Tripoli was never fully realized. Its construction was halted by the Lebanese Civil War which erupted in 1975. Original drawings were remained incomplete. The CMP team faced similar challenges to Sidi Harazem, and relied on in-depth research to retrieve archival materials dispersed between Lebanon and Brazil. An extensive tracing and interviewing process recorded narratives from people related to the project; contractors, consultants, construction workers, and the inhabitants of Tripoli. A shared online database allowed members in Lebanon and Brazil to deposit all of the information that was retrieved. In turn, this living archive allowed the CMP team to fill in the blanks.

Perseverance and creativity are necessary traits to retrieve missing data. When original drawings cannot be retrieved at all, relying on oral accounts and crowdsourced knowledge are necessary.

Once information is assembled, a diagnosis of the current condition of the modern heritage work is necessary. This is meticulous work—outlining the morphology of the site or building to identify the changes that occurred over time. Then, the CMP

23

team develops an understanding of the material, technical and programmatic problems, thereby informing conservation policies and their level of urgency.

Using data found about the original design, the multidisciplinary KIM grantee teams led onsite visits and surveys where they carefully studied the physical state of materials, furniture, appliances structural elements, as well as electrical, mechanical, and plumbing infrastructures. In addition, teams evaluated the building’s usages, management, maintenance, and monitoring. As a result all alterations and issues were charted and their causes were defined whenever possible. A variety of tools were employed to diagnose and verify damage such as the detailed study of the concrete panels of the facades of the Gandhi Bhawan and the development of a 3D structural analysis model in the Museum of Modern Art of São Paolo.

To summarize the findings and make them legible to stakeholders Shikha Jain and her team used tables while Aziza Chaouni used formatted sheets that cross-reference original drawings and current photos, marking all changes throughout.23

Recurring damages cited in the case studies are prevalent amid aging modern heritage worldwide: the oxidation of steel reinforcement, concrete cracks and spalling, concrete discoloration, obsolete electrical and plumbing systems, or recent additions that altered spatial qualities and materials.

A lack of maintenance and monitoring, poor funding, and low understanding of modern heritage value were common culprits that led to the damage of the various buildings and sites.

These issues also create challenges for long-term conservation efforts by undermining their viability. The non-existence of modern heritage listings and bylaws that promote conservation causes further threats to modern heritage in the Global South. It can sometimes result not only in insensitive programmatic shifts, like the rental of a floor as an office space in the National Library of Kosovo but also in abandonment and neglect like Neimeyer's International and Permanent Fairgound of Lebanon and portions of the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex.

4DEVELOP POLICY AND PREPARE A MANAGEMENT PLAN

The wide range of CMPs24 to conserve and sustain significance of the seven case studies demonstrates the versatility and flexibility of a conservation management approach that closely responds to the building’s needs, its context, and is rooted in research. The Gandhi Bhawan’s CMP directly referenced existing frameworks for the conservation of twentiethth-century structures such as the Madrid Document (Second Edition) of the ICOMOS-ISC2025 and the Eindhoven-Seoul Statement 2014 by DOCOMOMO International,26 while others developed their own conservation value systems that were crafted to suit their specific needs.

The seven CMPs also differed in their scope and scale. For instance, the CMPs for the Sidi Harazem Bath Complex which was still in-progress during the KIMMHUP workshop as well as Neimeyer's Permanent and International Fairground of Lebanon aimed to develop conservation masterplans at the

24

level of their entire sites while detailing solutions for specific elements. The Thermal Bath CMP outlined solutions for recurring technical problems while the Fair focussed on one building. Interestingly, both projects also faced strong development pressures and worked to integrate community and stakeholder collaboration throughout their CMP process.

On the other hand, the CMP for Lina Bo Bardi’s Museum of Modern Art of São Paolo concentrated on the building’s most significant feature, its structure, and focused conservation policies on solutions to fix the structural damage and ensure its long term safety.

The CMP for the Kosovo National Library followed a more conservative approach and proposed policies regarding specific features that were damaged or could likely affect the library’s integrity—focussing on structure, plumbing, additions, drainage, lighting, security, and the surrounding landscape.

The Gandhi Bhawan proposed a CMP where all conservation uses and interpretation proposals respect the two following values: (1) be mindful of the building’s sculptural form and symbolism as conceptualized by Pierre Jeanneret and his team and (2) that all of its elements should be the core focus behind any physical intervention.

The CMP for the METU Faculty of Architecture moved beyond typical preservation and repair tasks, and focused on strategies for raising awareness through a wide array of media including local and international exhibitions, design courses, publications, alumni outreach, a social media campaign, and a 3D model that combines photographic survey, diagnosis results, and

archival material. The CMP’s emphasis on outreach helped elevate the status of the building among the general public and affect the opinion of decisionmakers at the campus level. As a result, they came to see the METU Faculty of Architecture as an asset to Turkey’s cultural history as well as a key component of the University’s legacy and image on the national and international stage.

The Church of Atlantidá’s CMP focused on tactics to foster adaptability and resilience. The CMP proposed seventy-two conservation actions that can be adjusted to suit damage types, execution schedules, financing opportunities, and sociopolitical conditions surrounding the project. The seventy-two actions were organized by the level of urgency surrounding the damage, and the level of significance of specific features within three timeframes: short, medium and long-term. As such, this CMP approach seems particularly well suited to the limited funds available for conservation in the Global South and its fluctuating socioeconomic and political contexts.

5IMPLEMENT THE MANAGEMENT PLAN

Only the Church of Atlantidá in Uruguay has successfully implemented a portion of its CMP. Two others are on a good path to launch the implementation of their conservation policies. Indeed, phase one of the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex CMP is expected to start in the Fall 2020 with the rehabilitation of Zevaco’s craft market and its transformation into an exhibition space, while the Gandhi Bhawan received a 2020 KIM grant to restore the water basin and landscape surrounding the building.

25

These outcomes of the KIM program are both underwhelming and hopeful. They illustrate the persisting obstacles which prevent the conservation of modern heritage in the Global South; chiefly the recognition of modern heritage value and the commitment to funding the work necessary to protect these sites. Also, the success of the Church of Atlantidá should be nuanced since only the most pressing component of its CMP, the replacement of its roof, was implemented thanks to the support of the building owner, the Catholic Church, a well-funded entity. The wealthy and independent status of the Church should not overshadow the incredible lobbying work and awareness campaigns led by Circo Carabello. His tireless work brought recognition to Dieste as an important Uruguayan figure, through efforts such as the Dieste toolkit developed with the Ministry of Education in Uruguay. Ciro traveled between Uruguay and Mexico tirelessly, demonstrating the power of activism at the scale of one person. Ciro’s dedication confirms that it is possible to move mountains: seek funds internationally, change entrenched mentalities, respect the original intentions of the architect, and maintain the quality of the restoration against all odds.

26

27

Figure 5: Clay and wooden traditional water vessels used at the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Station.

28

Figure 6: A screenshot of the interview with Jordanian architect Ammar Khammash at Sidi Harazem as part of the KIMMHUP workshop. The full video can be seen at: www.kimmhup.com.

CONCLUSION

The seven case studies presented in this publication offer diverse methodological roadmaps for modern conservation in the Global South and highlight useful tools to handle prevalent hurdles such as the dispersal of archives, informality, development pressures, a lack of awareness, and precarious funds.

A brief comparison of the seven cases studies revealed that the monetary limit of the KIM grant resulted at times in incomplete conservation policies, which required further financial support— often to complete costly structural or material analyses or to facilitate a deeper focus on features of secondary or tertiary importance. Illustrations of this limitation are the two largest case studies— the Fair Grounds in Tripoli and the Thermal Bath Complex, whose individual buildings and landscape deserve a CMP in their own right. Similarly, the CMP for the Museum of Modern Art in São Paolo which focused on the building’s structure left other features of secondary significance understudied, such as the museum’s plaza and its landscape. These remain potential topics for further conservation studies.

With modern heritage preservation being still a nascent field in the Global South, the case studies presented in this publication and led by local architects offer insightful and unique experiences, enriched with access to international expertise and networks made possible through the KIM program. Throughout their processes, the case studies’ conservation plans were shared and discussed through a series of seminars held in London with the support of the 20th-Century Foundation and conservation experts Sheridan Burke and Susan

Macdonald. The KIM grant also enabled costly technical tests and access to international expertise, which would have otherwise been out of reach in the Global South. As such, these case studies stand as expectations. Yet they act as harbingers for the potentials of rehabilitated modern heritage.

29

6

ENDNOTES

1. Author Unknown, "Approaches to the Conservation of Modern Cultural Heritage (The Madrid New Delhi Document)." ICOMOS ISC20C, (2017).

2. Simon, Phipps, Brutal Outer London, (Tewkesebury: September Publishing, 2023).

3. Susan, Macdonald, "Modern Matters: Breaking the Barriers to Conserving Modern Heritage.” Conservation Perspectives 28, 1(2013): p.1

4. ICOMOS is an acronym for the International Council on Monuments and Sites. It is a non-governmental organization of professionals formed in 1965 with its headquarters in Paris. Its members participate in its activities in a voluntary capacity.

5. "Heritage Alert." ICOMOS. 2020. https://www.icomos.org/ en/get-involved/inform-us/heritage-alert.

6. Jukka, Jokilehto, "The World Heritage List: Filling the Gaps—An Action Plan for the Future." ICOMOS, (2004): p.15.

7. "Global Strategy for a Representative and Balance World Heritage List." UNESCO. 2020. http://whc.unesco.org/en/ globalstrategy/.

8. Gwendolyn, Wright, "Building Global Modernisms." Grey Room 6, (2002): p.125.

9. Janet L., Abu-Lughod, Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981).

10. Paul, Rabinow, Colonialism, Modernity: the French in Morocco, in Forms of Dominance: On the Architecture and Urbanism of the Colonial Enterprise, ed. Al-Sayyad (Brookfield, VT: Avebury Publishing, 1992). p. 170-82.

11. Zeynep, Celik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997).

12. Lynn, Schler, "Ambiguous Spaces: the Struggle Over African Identities and Urban Communities in Colonial Douala, 1914-45.” Journal of African History 44, 1 (2003): p. 51-72.

13. Mia, Fuller, "Building Power: Italian Architecture and Urbanism in Libya and Ethiopia." in Forms of Dominance. On the Architecture and Urbanism of the Colonial Enterprise, ed. Nezar AlSayyad (Aldershot, Brookfield: Avebury, 1992), p. 211–39.

14. Christopher Rausch describes Global Heritage Assemblages as transnational networks of governmental, intergovernmental, and nongovernmental organizations, as well as private individuals and corporate actors who engage with modern heritage in the form of colonial and postcolonial architecture and urban planning. Christoph, Rausch, Global Heritage Assemblages : Development and Modern Architecture in Africa, (New York, NY : Routledge, 2017).

15. The Conservation Management Plan (CMP), a strategic roadmap for conservation detailed in the first chapter of this publication by the modern heritage expert Sheridan Burke, has seven phases: 1) understand the place, 2) assess cultural significance, 3) identify all factors and issues and 4) develop policy, 5) prepare a management plan, 6) implement the management plan, and 7) monitor the result and review the plan.

16. ICOMOS, The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, (Burwood, Australia: Australia ICOMOS Incorporated, 2013).

17. Critiquing Turkish architects’ uncritical transfer of modern architecture at the time, the Turkish architectural critic coined the term Hiltonism in his seminal 1958 article, published in the weekly news magazine Kim, titled: "Hiltonculuk". Vanli, Sevki, "Hiltonculuk," Kim-Haftalik Haber Dergisi (November 28, 1958), p. 21-22.

18. Eren, Gazioglu, "Politics and architecture in Turkey (1923 – 1960)." Estudo Prévio 11, Centro de Estudos de Arquitecture, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, (2017): p.14.

19. For a thorough bibliography of Andrija Mutnjaković’s works please refer to: http://info.hazu.hr/en/member_of_academy/personal_pages/a_mutnjakovic_en/a_mutnjakovic_bibl_en/ retrieved July 15th 2020.

20. Udo, Kultermann, Architecture in Former Yugoslavia, in Architecture in the 20th Century (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993).

21. Udo, Kultermann, New Architecture in Africa, in Architecture in the 20th Century (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993).

22. Aziza, Chaouni, "Agadir: the Coming of Age of Morocco's Post-Independence Modernism." Essay. In SOS Brutalism, (Zürich: Park Books, 2017). p. 52–57.

23. The diagnosis phase of the Sidi Harazem project was not completed at the time of the KIMMHUP workshop and hence it is not described in the chapter on Sidi Harazem in this publication.

24. The complete CMPs of all KIM grantees included in this publication, in addition to CMPs of grantees since the program inception in 2012 can be found in this website: https:// www.kimmhup.com/

25. Author Unknown, "Approaches to the Conservation of Modern Cultural Heritage (The Madrid New Delhi Document)." ICOMOS ISC20C, (2017).

26. "Eindhoven-Seoul Statement 2014." DOCOMOMO International, (2014). Accessed June 2020. http://www.DOCOMOMO. com/pdfs/about/eindhoven/051623_110638_2014-09-26 Eindhoven-Seoul Statement 2014.pdf

30

31

CONSERVING MODERN HERITAGE PLACES UNDER PRESSURE

THE ROLE OF CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLANS

BY SHERIDAN BURKE, AUSTRALIA

CONSERVING MODERN HERITAGE PLACES UNDER PRESSURE

The Role of Conservation Management Plans

Too many of the heritage places and sites of the twentieth-century remain at risk. Although appreciation of mid-century modernism is increasing in some regions, the range of buildings, structures, cultural landscapes and industrial sites that are characteristic of the twentieth century are still threatened by a general lack of awareness and recognition. All too often they are pressured by redevelopment, unsympathetic change, or simply by neglect.1

The sweeping economic, social, technological, and political developments of the twentieth century produced unprecedented change. Two World Wars, the Cold War that followed, the Great Depression, and decolonization all significantly altered the fabric of society over the course of the twentieth century.

Rapid urbanization and the growth of large cities, accelerated technological and scientific development along with the emergence of mass communications and transportation— fundamentally changed the way we lived and worked—producing new buildings and structures, unprecedented building types and forms, often using experimental materials and construction techniques. Massively changed landscapes were created through industrialization and mechanized agriculture.

And yet, comparatively few of the sites and places created by such tumultuous events have been listed and protected for their heritage values.

34 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 1a: Sirius Public Housing, Australia.

1 SIX BUILDINGS OF MODERN HERITAGE VALUE- SIX STORIES OF THREAT

The obligation to conserve and manage the heritage places and sites of the twentieth century is as pressing and important as our duty to conserve the significant cultural heritage of previous eras.

However, behind almost every modern heritage site conserved there is also pressure for change. Converting a lack of appreciation for the site into growing respect and pride by resolving a range of maintenance, material, and use-related issues is necessary.

This essay includes several such stories, to share experiences and introduce key management tools that will support the future of modern heritage conservation;

1. the Conservation Management Plan process, as is used by the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern (KIM) program and

2. Approaches for the Conservation of TwentiethCentury Cultural Heritage prepared by the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Twentieth Century Heritage (ISC20C).

Many modern buildings, structures and landscapes around the world are under threat- here are six which are presently under threat. They are all the subject of international Heritage Alerts by the ICOMOS Twentieth Century Heritage International Scientific Committee.

35

36 SHERIDAN BURKE

All too often the heritage values of significant Modern heritage sites are not understood, or appreciated, but over the last decade this has begun to change.

Figure 1b: Y Block, Norway.

1.1 THE VIKING SHIP HALL IN ROSKILDE, DENMARK (1967-68)

This design by Erik Sorenson was the first late modern building to be listed for protection in Denmark in 1998. Following dramatic floods in 2013 and a subsequent escalation of structural issues, the Danish Minister of Culture Mette Bock- against the advice of her own experts and the advice of the Department of Culture- decided to de-list the building. The Roskilde Viking Ship Museum intends to demolish the building.

1.2 THE AL SAWABER COMPLEX, KUWAIT (1977)

This housing complex was constructed in 1981 to a design by Canadian architect, Arthur Erickson. Currently proposed for demolition after a long period of vacancy, it occupies a large and very valuable site in the centre of the city of Kuwait.2

1.3 MIYANONOJO KAIKAN, JAPAN (1966)

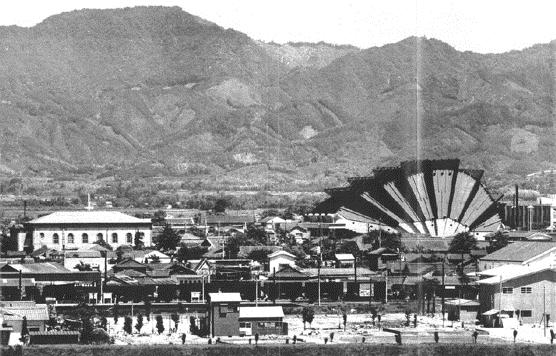

Metabolist architect Kiyonori Kikutake’s civic hall has been vacant for ten years and virtually without maintenance during its lease to a University. Demolition was recently approved by the Miyazaki Prefecture Council, despite international alerts issued by DOCOMOMO and ICOMOS.3

37

Figure 1c: Miyanonojo Kaikan, Japan.

1.4 SIRIUS BUILDING IN SYDNEY (1978)

Canadian architect Tao Gofers designed this public housing complex currently being converted for use as luxury apartments. The property was sold following the state government’s decision to refuse heritage listing in 2017—against the advice of the Heritage Council of New South Wales. The building was put up for sale with development or demolition as options.4

1.5 MOSCOW RADIO TOWER, MOSCOW (1919-1922)

Vladimir Shukhov designed this pioneering hyperboloid steel structure. The tower construction is an entirely Russian concept that influenced structural engineering and architectural creativity for over a century globally. It is one of the modern icons of our time. No longer in use, a lack of maintenance threatens the Shukhov Tower.

1.6 Y BLOCK, OSLO (1969 )

Designed by Erling Viksjø, the Y Block is comprised of two buildings. They are Norway’s most important symbols of post-World War II optimism, representing a belief in international democracy, dialogue, and openness. The project included artistic contributions from Pablo Picasso to the building facades. Overriding extensive local and international protests, the Norwegian government proposes its demolition after damage from a terrorist attack and ongoing security concerns for the site.

These buildings and structures at risk share a common trait: they each (initially) lacked public awareness of their heritage significance. This led to a lack of popular support and absence of political will to conserve them. Sometimes lack the appropriate methods and technical approaches to effectively conserve them was also evident.

38 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 1d: Al Sawber Complex, Kuwait.

39

The obligation to conserve and manage the heritage places and sites of the twentieth century is as pressing and important as our duty to conserve the significant cultural heritage of previous eras.

Figure 1e: Viking Ship Hall, Denmark.

Figure 1f-g: Moscow Shukhov Radio Tower, Russia.

LACK OF PUBLIC AWARENESS OF THE SIGNIFICANCE OF MODERN HERITAGE PLACES

All too often the heritage value of significant modern heritage sites is not understood or appreciated. However, over the last decade, this has begun to change. The World Heritage List’s inclusion of sites from the modern era has increased dramatically. This is largely due to concerted efforts by UNESCO and Non-Government Organisations such as ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites, formed in 1965 ), DOCOMOMO (Working Party for the Documentation and Conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement, formed in 1988), and TICCIH (The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage, established in 1999).

In 2001, the UNESCO World Heritage Centre with ICOMOS and DOCOMOMO launched a joint program for the identification, documentation, and promotion of modern heritage by organizing six regional meetings to identify global issues and trends, which were held 2001-2006.

In 2004, the seminal analysis by ICOMOS of The World Heritage List: Filling the Gaps - an Action Plan for the Future confirmed that modern heritage was under-represented on the List, with the implication that it was probably similarly underrepresented in national and local heritage lists and protection.

During the first thirty years of the World Heritage Convention (1972-2001), only fourteen modern sites were listed but during the next fifteen years (to 2017) more than forty modern heritage sites were listed and many World Heritage tentative lists show other nominations that are in preparation by national parties. Recognition and awareness is growing.

40 SHERIDAN BURKE

2

Figure 2a: Abraj Al Kuwait, Kuwait.

Figure 2b: Robie House, USA.

41

Figure 2d: Paimio Sanatorium, Finland.

Figure 2c: Robben Island, South Africa.

These world heritage listings include cities such as Brasilia the new capital of Brazil, Le Havre in France, Asmara in Eretria, as well as parts of Rabat in Morocco. Also included are large housing complexes such as the Berlin housing estates and individual buildings and structures from a radio station in Sweden, to a hospital in Finland, and an Opera House in Australia. Mexican universities and a range of modern houses and churches across the globe, even water supply towers in Kuwait have been added to tentative lists or nominated to the World Heritage List in recent years.

Serial nominations of works by prominent modern era architects- Antonio Gaudi, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier have now been listed with many more proposed on tentative World Heritage nomination lists such as a selection of buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright.5 And of course, similar modern heritage listings are (perhaps more slowly) coming forward at national and local levels for management and protection. More visibly there has been a rise in local community advocacy and international social media campaigns to save and conserve modern heritage sites.

In 2005 ICOMOS initiated the formation of an international scientific committee, the ISC20C, which is focussed on advocacy and the development of guidance documents for the whole spectrum of twentieth century heritage sites. The ISC20C quickly grew to be one of the biggest ICOMOS committees, very active in advocacy work. The committee focused not on architectural styles or periods but on identifying and conserving the heritage of an entire century. It was a bold initiative, drawing on interdisciplinary expertise and experience which has produced advice, analysis, and practical

42 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 2e: Pampulha Modern Ensemble, Brazil.

guidance to support a broader exploration of heritage values.

The International Union of Architects (UIA) has initiated an international Twentieth Century Buildings Register. National DOCOMOMO working parties were developing lists of important buildings, structures, and landscapes. TICCIH has researched thematic studies of important industrial typologies (bridges, collieries, canals, railways, etc.)—all actions that were instrumental in changing public awareness over time.

However, identifying and listing the heritage significance of modern sites is only part of the battle. Managing each site’s practical conservation can also be challenging.

The ISC20C has prepared two seminal documents to provide guidance both about identifying significant modern heritage places. In pre-publication is The Twentieth-Century Historic Thematic Framework. 6 Guidance about how to manage sites is in Approaches to the Conservation of TwentiethCentury Cultural Heritage: The Madrid New Delhi Document.7

43

Figure 2f: Brasilia, Brazil.

APPROACHES APPROACHES APPROACHES APPROACHES TO TOTO TO THE THE THE THE CONSERVATION CONSERVATION OF OFOF

TWENTIETH TWENTIETH--CENTURY CENTURY CULTURAL CULTURAL HERITAGE HERITAGE

44 SHERIDAN BURKE

MADRID – NEW NEW DELHI DOCUMENT 2017

MADRID

ICOMOS INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE ON TWENTIETH CENTURY HERITAGE

Figure 3: The cover of the MND document, 2017.

LACK OF UNDERSTANDING OF METHODS TO CONSERVE AND MANAGE MODERN HERITAGE PLACES

A major source of pressure opposing conservation is a lack of understanding of how to look after modern heritage places. The use of contemporary materials and construction methods (often experimental), lack of maintenance, repair challenges, changes, or loss of use, and new user needs (security, upgraded servicing, AC, etc.) are often cited as insurmountable problems for conserving modern heritage places. Climate change is quickly exacerbating issues for heritage sites as well. Slowly, there has been increasing access to practical guiding documents and technical advice for managing and conserving modern heritage materials and sites. These have been developed in diverse cultures internationally and are all available for use and adaptation.

From the late nineteenth-century writers like William Morris, John Ruskin,8 and Cesar Brandi9 began to explore the theory and reasons for conservation. Debates evolved into charters such as the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings Manifesto (1877) and much later the 1964 Venice Charter which stimulated a new generation of debate and adaptation of theory to local circumstances. From the 1970s, the increased international sharing and debate about conservation planning methodologies, prompting regionally specific developments such as the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter of 1979, JS Kerr’s The Conservation Plan 1982, and then by Bernard M. Feilden and Jukka Jokilehto’s World Heritage Site Management Guidelines (ICCROM 1998). Throughout the 1980s international professional organizations like ICOMOS, TICCIH, and DOCOMOMO began to focus particularly on the

issues of identifying and listing significant modern heritage places and national groups such as the Twentieth Century Society in the UK were at the forefront of such advocacy.

4SPECIFIC APPROACHES FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TWENTIETH CENTURY CULTURAL HERITAGE

There has been much discussion as to whether specific guidelines for conserving places of the modern era were separately needed. Many professionals argued that existing conservation approaches could be readily applied to heritage places of the twentieth-century.

In 2010 the members of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Twentieth-Century Heritage (ISC20C) began to draft a reference text for an international charter where they set out the approach and the principles that should be applied to managing and interpreting twentieth century sites. The ambitious objective was to provide an international benchmark document.

Lively debates ensued amongst members, drawing on their pragmatic experience from all regions of the world. Conferences, meetings, and broad consultations were undertaken internationally. The resulting final text Approaches for the Conservation of Twentieth-Century Cultural Heritage, colloquially called The Madrid New Delhi Document, was developed and revised from 2011-2017 and is now translated into seventeen languages10, an indication of the need for such an international guidance document and benchmark standard. It has proved adaptable for conserving and managing heritage

45 3

places of various typologies and scales—from mass public housing schemes, to infrastructure systems, skyscrapers, sports stadia, urban parks, and cultural landscapes.

This short document provides eleven basic articles and thirty-two more detailed principles follow. It is short, concise, and a great reference resource in practice. The basic articles are:

Article 1: Identify and assess cultural significance.

Article 2: Apply appropriate conservation planning and management methodology.

Article 3: Research the technical and planning aspects of twentieth-century cultural heritage.

Article 4: Develop policies to conserve significance.

Article 5: Acknowledge and manage pressures for change, which are constant.

Article 6: Manage change sensitively.

Article 7: Ensure a respectful approach to additions and interventions.

Article 8: Recognise when the use contributes to the significance and manage accordingly.

Article 9: Respect the authenticity and integrity of the site

Article 10: Consider environmental sustainability.

Article 11: Promote and celebrate twentieth century architectural heritage with the wider community.

I commend it to you as the single most useful guidance document available today for modern heritage conservation.

5CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLANS IN PRACTICE

It is within this international framework that one of the most practical and useful methodologies available to support the survival and adaptation of modern heritage places has been establishedConservation Management Plans, (CMPs) which are the primary tool explored through this publication— and what is happening here at Sidi Harazem as a result of the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern grant process.

My professional practice in Sydney is based on supporting owners and agencies to recognize and cherish the values of modern heritage places and manage them well for sustainable futures.

I work on modern heritage places all over the world, from Tokyo to Kuwait, Sydney to Los Angeles, from stadiums, to private houses, water towers, opera houses, and telescopes. Each of them has challenges, different management requirements, and a specific cultural context—yet they have all successfully adapted the CMP process to meet their resources and challenges.

After over thirty-five years of practice, teaching, and applying the CMP approach, I can reflect and say that in each case the key to successfully developing any type of plan to sustain a heritage site is an excellent understanding of why the place is significant.

This is a very different starting point to the usual analysis of condition and repair schedules that characterize historic structure reports, or detailed histories of building fabric. The CMP methodology requires a deeper understanding of why the place is significant. This knowledge – summarised in a

46 SHERIDAN BURKE

47

Figure 4: The KIM CMP flowchart.

short (100 word) statement of significance becomes the foundation for all that follows.

The second key to success is collaborating well with your stakeholders. They will have the long-term role and responsibility towards the site, and an understanding of operational realities. Stakeholders include people who work in government agencies, community groups, construction supervisors, project managers, school groups, property owners, professors, architects, politicians, tourism authorities, and others with vested community interest in the successful conservation of these sites. Close and frequent collaboration with all stakeholders is important as the CMP is developed.

Understanding the significance of the site is key before engaging effectively with stakeholders—as it will lead to direct actions and policies. This is the basis of the Getty’s Keeping It Modern program which has now completed fifty-four projects in all corners of the world. These project reports are being loaded into the Getty Foundation online library. In all of these conservation projects a standard five-

step process has been used and adapted. The same five logical steps of the conservation process are reflected in a Conservation Management Plan (or its international equivalent). A CMP, or conservation plan (these terms are often used interchangeably) can best be explained by a quote from Dr. James Semple Kerr:

At its simplest, a conservation plan is a document that sets out what is significant in a place and consequently, what policies are appropriate to enable that significance to be retained in its future use and development. For most places, it deals with the management of change.

James Semple Kerr, 201311

A good CMP is:

• Interdisciplinary: Developed with historians, architects, planners, landscape specialists, sometimes archaeologists and collections managers

• Collaborative: Prepared with stakeholders, not

48 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 5a: The Kosovo National Library, Kosovo.

delivered to them

• Succinct: The shorter and more visual the betterComprehensive: Based on all heritage values, not only on architecture

• Evolutionary: An iterative process which evolves as knowledge grows

• Engaging: Based on policies agreed upon with stakeholders, not imposed upon them

CMPs are based on well-established international conservation practices that are now formalized in national charters and legislation in many parts of the world. CMPs are mandatory requirements for all places on the World Heritage List. They embrace the values-based approach to conservation that is practiced and promoted by most international conservation institutions today. Values-based conservation requires comprehensively looking at all the reasons a place is significant, and avoids relying solely on the architecture or building fabric of a place.

One of the real benefits of a CMP is that it moves conservation from being a reactive process—"what repair do I need to do next?"—to a more proactive approach. A proactive approach asks—"what are the policies that need to be put in place for upcoming or future conservation work?" CMPs are a powerful tool to help determine funding needs in the short, medium, and long term. They establish a framework for decision-making and help to prioritize investment by owners.

It’s not just the content that makes a CMP different from a property management plan or an historic structure plan. It is the process, a simple logical development that progresses through understanding the site well (including its history and physical elements) into an explicit assessment of significance. This is then used to directly formulate policies designed to protect that significance in the long term.

49

Figure 5b: The METU Faculty Building, Turkey.

One of the real benefits of a CMP is that it moves conservation from being a reactive process -what repair do I need to do next?; to a more proactive approach.A proactive approach askswhat are the policies that need to be put in place for upcoming or future conservation work?

50 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 5c: Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Station, Morocco.

Figure 5d: The Gandhi Bhawan, India.

51

Figure 5e: The Atlantida Church, Uruguay.

Figure 5f: Tripoli Fairground, Lebanon.

6CONSERVATION PLANS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Like heritage sites, every CMP is unique. However, they all share the following five-step process.

The Sidi Harazem Keeping It Modern workshop that took place in February 2019 and gave rise to this publication shared the CMPs processes from seven Getty Keeping It Modern grant recipients. Maya Hmeidan presented the start of her CMP of Niemeyer’s Tripoli Fair, Aziza Chaouni discussed the ongoing CMP of Zevaco’s Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex, Shika Jain detailed the work on the Gandhi Bhawan in Chandigarh, and Ciro Carabello presented on his work on the brick buildings of Dieste in Uruguay with a focus on how community members (especially children) are engaging with the CMP.

The CMP process, as explained in figure 4, is a formal framework to explain the thinking process and approach for conservation. CMPs are a tried and tested methodology that provides a framework for organizing all of the information needed to make appropriate and consistent decisions about the conservation of a place based on the internationally recognized processes for conserving heritage. I’ll briefly introduce the five-steps to you, using as examples two CMPs I’ve recently been involved with The Eames House in California and the Sydney Opera House (SOH) to illustrate how they apply in practical terms.

52 SHERIDAN BURKE

"At its simplest, a conservation plan is a document that sets out what is significant in a place and, consequently, what policies are appropriate to enable that significance to be retained in its future use and development. For most places it deals with the management of change."

JAMES SEMPLE KERR, 2013

53

Figure 6: Sydney Opera House, Australia.

6.1 UNDERSTAND THE PLACE

Identifying the heritage values of a place and developing a deep understanding of these values as the basis for conservation decisions, has been the basis of conservation practice for a long time. Understanding significance means historical research and analysis, documentation, possibly documenting oral histories, and always stakeholder consultation.

It’s not just about the architecture. Step one requires investigating the setting, the contents, the collections, the landscape, and archives that all contribute to its significance.

6.2 ASSESS ITS SIGNIFICANCE: WHY? TO WHOM?

The significance of a place is of course often most evident in the building’s physical fabric but not exclusively, it can also be significant for its form, function (or use), location, and intangible values.

I’ve been a member of the Sydney Opera House Conservation Council for a decade, and we use the assessment of significance in our CMP as an essential tool to guide decisions about change daily. Issues such as use, spatial qualities, spatial sequences, connections with certain communities, setting, cultural practices, and so on are all attributes of the SOH that contribute to its significance.

For example, the Sydney Opera House is located on a site called Tubowgule- “where the knowledge waters meet,” a place of gathering and feasting for Indigenous Australians. These indigenous values of the place precede the modern era creation of the

Sydney Opera House by tens of thousands of years. Yet, for many, it’s the architectural masterpiece itself that is thought to be of significance.

At the Eames House, in Los Angeles, several intangible values contribute to its significance. It is Ray and Charles Eames’ way of living in the meadow landscape that reflects their unique design approach. As well, the collection of objects inside the house is a critical element of its significance, not just the iconic building.

This very personal connection between place, practice, and the working life of the Eames’ was captured and turned into policies and conservation actions.

The way the Eames situated the house in its landscape setting—close to an existing row of eucalyptus trees also contributed to the house’s overall significance.

Stepping through the five stages of the CMP process ensures that these values are captured—beyond the usual building fabric-centred approach.

6.3 GATHER INFORMATION TO INFORM POLICIES.

WHAT? WHO? WHY?

What are the elements of the site that are significant? It’s setting? Its archives or collections? Who are the stakeholders interested in its future?

Which oral histories might be accessible? What external factors are influencing the place? Building codes? Development pressures? Repair and condition concerns? These are some of the many questions that arose during Step 3 research and consultations.

54 SHERIDAN BURKE

In 2002 we had the great privilege of engaging with Jan Utzon and his son to develop the Utzon Design Principles for the Sydney Opera House. These principles describe how the original architect saw opportunities to manage change at the site. At the Eames House, oral history interviews with the Eames family members provided similar valuable insights.

6.4 DEVELOP CONSERVATION POLICIES TO SUSTAIN SIGNIFICANCE SETTING, CONTENTS, BUILDINGS, ARCHIVES. HOW? WHO? WHAT?

Methods used to conserve the site can only be determined by understanding its significance and writing policies and actions that will help sustain those values. An expert assessment needs to be

made as to how much change can the site elements will tolerate before their significance is lost.

Within the CMP for the Sydney Opera House a tool called 'Tolerance for Change' is used, enabling staff to quickly assess the impacts of actions needed to operate this busy living heritage site on a practical day-to-day basis (section 4.4.12) Respecting the Vision: the Sydney Opera House CMP (2017).

6.5 IMPLEMENT AND MONITOR THE CMPTHROUGH WORKING WITH STAKEHOLDERS

In every CMP there are usually recommendations for detailed research. At the Eames House, one of their iconic furniture designs the 'hang it all' has been used to show the central nature of the CMP and the range of associated research and documentation (fig. 8).

55

Figure 7: Eames House, USA.

56 SHERIDAN BURKE

Figure 8: Eames CMP Hang it All.

Figure 9: TWA terminal, USA.

A CMP is usually prepared by a professional conservation practitioner who is working closely with the building owner or manager and in consultation with site’s stakeholders. It is always an iterative process. To be successful, a CMP needs buy-in by the owner and the person responsible for the ongoing care and conservation of the place. Ensuring their involvement throughout the process is vital. At the Sydney Opera House, a detailed induction process occurs for every new staff member or contactor on-site, so that everyone is aware of its heritage significance and the need to care for it accordingly.

7IN CONCLUSION

To conclude on a positive note, the TWA terminal at JFK airport New York, completed by Eero Saarinen in 1962 for Trans World Airlines, is an iconic modern building no one thought could be saved. The building was closed in 2001, and left vacant since it was unable to support servicing the size of modern aircraft. Re-opened in 2019 after a major rehabilitation, it has become one of the most popular hotels at JFK airport, demonstrating that even such a highly specific function and location can be adapted and celebrated for modern use. This is a great example demonstrating future potential for modern heritage sites under pressure.

ENDNOTES

1. Sheridan, Burke. "Approaches to the Conservation of Modern Cultural Heritage (The Madrid New Delhi Document)" ICOMOS ISC20C, (2017).

2. Demolished 2019.

3. Demolished 2019.

4. Undergoing conversion for hotel, 2019.

5. A selection of 8 Frank Lloyd wright buildings were listed in 2019.

6. Susan Marsden & Peter Spearritt, "The Twentieth-Century Historic Thematic Framework: A Tool for Assessing Heritage Places," GCI. (2020).

7. "Approaches for the Conservation of Twentieth-Century Cultural Heritage (The Madrid New Delhi Document)" ICOMOS ISC20C, (2017)

8. John, Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1849).

9. Cesare, Brandi, Theory of Restoration, ed. Guiseppe Basile, trans. Cynthia Rockwell (Firenze, Istituto Centrale per il Restauro and Nardini Editore, 2005).

10. Translations available on the ISC20C website.

11. James S., Kerr, The Conservation Plan (Australia ICOMOS, 2013).

57

NIEMEYER’S INTERNATIONAL AND PERMANENT FAIRGROUND OF LEBANON

THE CHALLENGES OF CONSERVING A UTOPIAN VISION

MAYA HMEIDAN, LEBANON

OSCAR

OSCAR NIEMEYER’S INTERNATIONAL AND PERMANENT FAIRGROUND OF LEBANON

The Challenges of Conserving a Utopian Vision

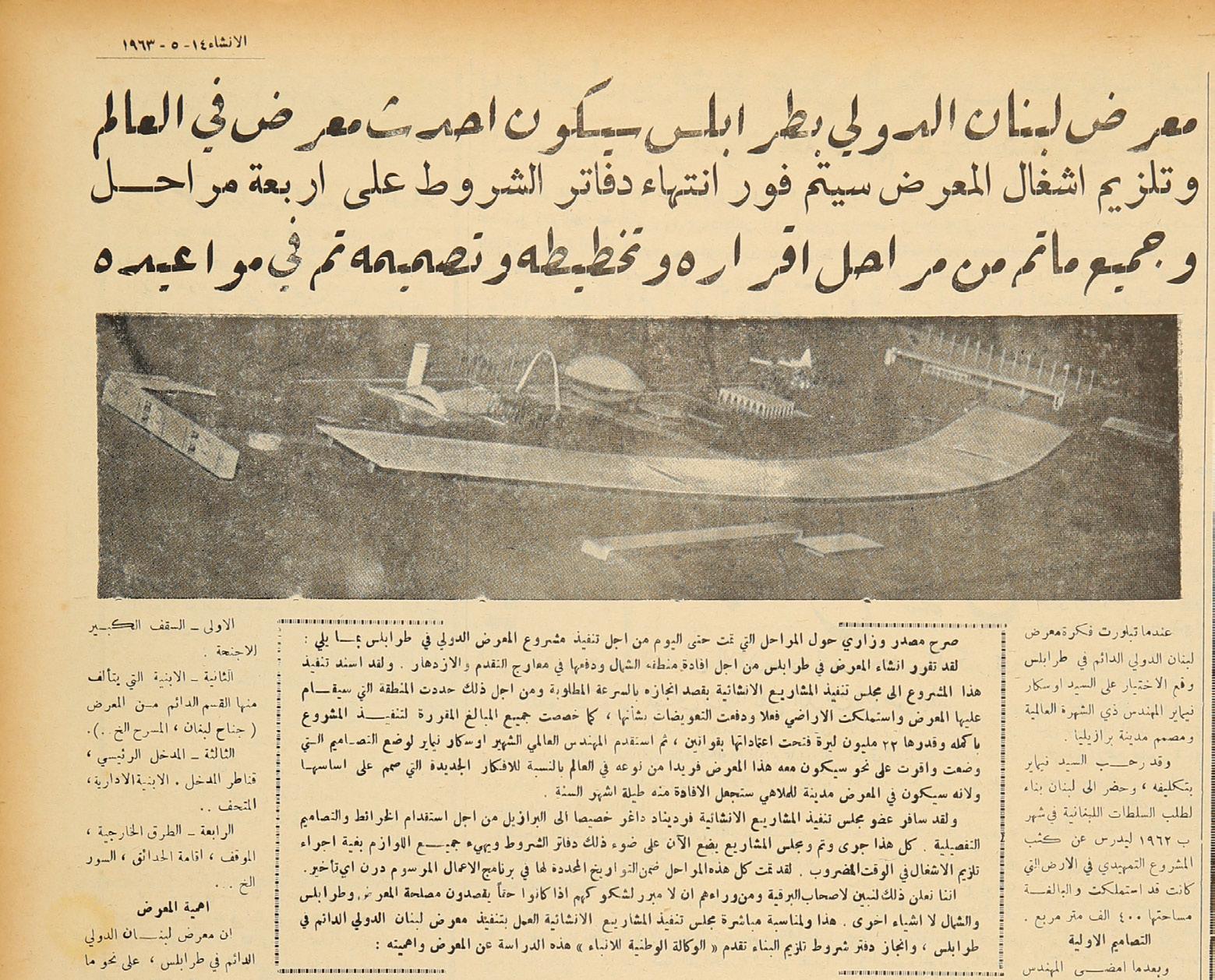

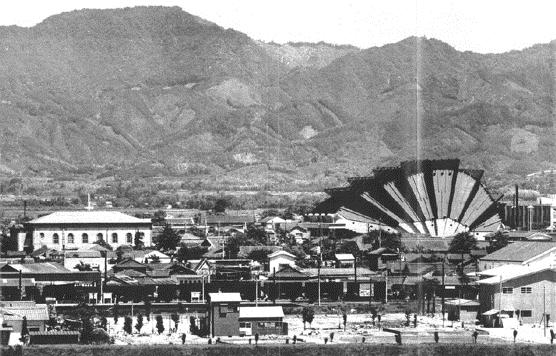

1INTRODUCTION