Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 - 1990 And 2021 - 2022

ISBN: 978-1-955260-66-4

Front Cover: Installation Li Trincere Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022 at David Richard Gallery

Title Page: Installation Li Trincere Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022 at David Richard Gallery

Back cover: IInstallation Li Trincere Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022 at David Richard Gallery

Installation Li Trincere Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022

January 7 - February 23, 2023

Published by:

David Richard Gallery, LLC,

526 West 26th Street, Suite 311, New York, NY 10001 www.DavidRichardGallery.com

212-882-1705 | 505-983-9555

DavidRichardGalleries1 DavidRichardGallery

Gallery Staff:

David Eichholtz and Richard Barger, Managers

All rights reserved by David Richard Gallery, LLC. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in whole or part in digital or printed form of any kind whatsoever without the express written permission of David Richard Gallery, LLC.

Artwork: © 1986 - 2022 - Li Trincere

Catalogue: © 2023 David Richard Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

Essay: LI TRINCERE Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022 by David Eichholtz

Essay: LI-TRINCERE: HARD EDGY by Peter Frank

Catalogue Design: David Eichholtz and Richard Barger, David Richard Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

Artwork © Li Trincere

Images by Yao Zu Lu

DAVID RICHARD GALLERY

Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 - 1990 And 2021 - 2022

LI TRINCERE

Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 – 1990 and 2021 – 2022

David Richard Gallery is pleased to present two simultaneous exhibitions by New York artist Li Trincere that span four decades of her studio practice focused on hard edge, geometric paintings. The first presentation includes earlier paintings dating from the late 1980s through the early 1990s. The second presentation debuts her newest series of paintings created in 2022 as well as selections of recent paintings from 2021, both conceived and created during the covid pandemic and funded with the assistance of a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. While the primary focus of both exhibitions is Trincere’s paintings, drawings are an integral part of her art making and produced in parallel with paintings. Both paintings and drawings are conceived and produced as stand-alone works and rarely is there a painting corresponding directly to a drawing. Each presentation includes a selection of representative drawings corresponding to each time period, all are all produced with Caren D’ache wax crayon on BFK paper measuring 22 x 30 inches in a standard horizontal format.

This exhibition is not a retrospective, but rather a close look at two discrete bodies of work separated by three decades. A lot happened aesthetically for Trincere in those intervening decades: exploring complex geometric shapes; combining and layering internal shapes with the literal perimeters of the canvases; creating internal compositional torque and tension; contrasting matte versus sheen surfaces; adding metallic flecks; combining spatial depth with complimentary perimeters of canvases. These empirical approaches all led to Trincere’s signature color palettes, internal banding and corresponding vector shapes (iconic shards of negative space), pristine surfaces, literal shapes, and illusory space. Taking inspirations and external influences and making them her own visual language brought more than nuance to her paintings, they map a successful trajectory and thoughtful maturation realized in the newer paintings. Many of the series of paintings from the past two decades have been the subject of three solo exhibitions since 2018 at David Richard Gallery.

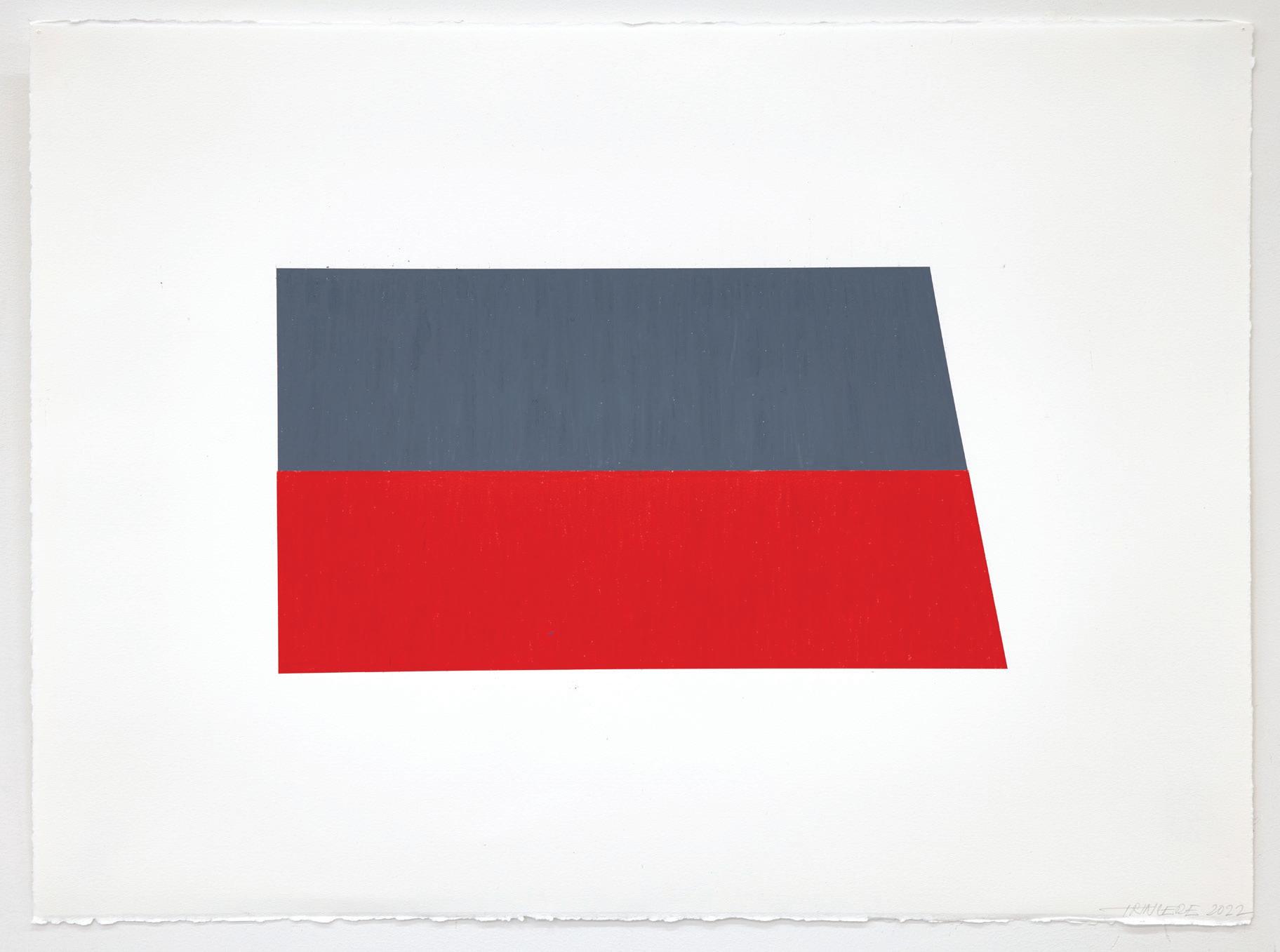

Throughout her career Trincere has remained committed to non-objective painting focusing solely on primary shapes (squares, polygons, quadrilaterals, trapezoids, X’s, and

various combinations and permutations as noted above) and using primary colors to provide a pop and contrast against reductive palettes of mostly black and white. The more things change in the world around her, both culturally and aesthetically, in New York City and the art world respectively, Trincere does not waiver in her devotion to hard edge, geometric painting. More important, she continually finds ways to both refine and perfect her approach, as well as reinvigorate and challenge her studio practice as seen in the most recent paintings. Hence, the similarity observed between her two bodies of paintings separated by three decades: a cohesive approach, but with elevated enhancements such as dynamic compositions, unique color palettes, and enigmatic surfaces in her newest series.

This pair of simultaneous exhibitions will be documented with a digital catalog and essays by Peter Frank, a Los Angeles-based art historian, curator, and critic, and David Eichholtz, based in New York, an art historian, curator, and co-founder of David Richard Gallery. Peter Frank began his career in New York, he knew Li Trincere in the early 1980s and saw most of the earlier paintings in this presentation either in her studio or exhibitions in New York.

Frank had first-hand knowledge of the art scene in East Village and knew most of Trincere’s male contemporaries: Ted Stamm, Olivier Mosset, Alan Uglow, Steven Parrino, Michael Scott, and Mark Dagley to name a few. It is interesting to note that in the early 1980s, Trincere was one of the few women emerging in the arena of hard edge, geometric painting, several of her female colleagues at that time included Joan Waltemath, Suzan Frecon, and Mary Obering.1 Not just the women had a tough go of it, so did the cadre of artists as a whole who chose to pursue not only rigorous geometric abstraction, but maintained their unwavering loyalty to painting as a medium. Trincere and her Neo-Geo colleagues bucked the mainstream of popular art in New York during the 1980s, which included Street and Graffiti Art, Scatter Art, Neo-Expressionism, Pictures Generation Artists, abject art, identity art, and photography.

About the Exhibition:

The exhibition of eleven earlier paintings from 1986 – 1990 are all on stretched canvas-

es with shaped perimeters, a cornerstone of Trincere’s studio practice. The exception is Untitled (T22), 1987, measuring 10 x 120 inches and comprised of 2 canvases, each 10 x 60 inches, held together with screws, and a unique composition: dynamic black and white geometric shapes with a central diamond and series of chevron shapes to the left and right. The three paintings measuring 36 x 36 inches and the two large “X” paintings measuring 72 x 72 inches (color palettes of one Black and White and the other Black and Green, both diptychs comprised of a pair of 36 x 36-inch canvases) were presented, along with other paintings not in this presentation, at Galerie Rolfe Ricke in Cologne, Germany in a solo presentation in 1989 and group presentations at the Cologne Art Fair in 1988 and 1990. Trincere continued exhibiting her paintings with Rolfe Ricke well into the 1990s and until he retired. Nearly all the other paintings in this exhibition were presented at the Julian Pretto Gallery in New York. The painting, Untitled (T09) Red/White, 1987, measuring 48 x 48 inches, was also presented in a group presentation at Annina Nosei Gallery, New York. There are also eight hard edge, geometric drawings of Caren D’ache wax crayons on BFK paper, each measuring 22 x 30 inches and created from 1986 to 1991. The imagery on paper mostly corresponds to the paintings in the presentation.

The simultaneous and second exhibition in a separate gallery space (Suite 9E) debuts new paintings from 2022 and recent paintings from 2021, as well as a selection of drawings dating from 2020 to 2022. The interesting and noteworthy aspect of the newer paintings is that they do not have shaped perimeters, they are all a fixed dimension of 54 x 54 inches square, a significant departure for Trincere. Since these two recent series of paintings emerged during the covid pandemic, the prescribed and consistent shape and dimensions almost echoed the confinement the artist experienced during the pandemic. However, the fixed shape and size of each canvas and series was not a limitation for the artist. In fact, the restraints became a source of innovation and experimentation for Trincere. She pushed geometry, figure / ground relationships, compositions, color palettes, value transitions, and surfaces to the limit.2 Oddly, at first glance each painting almost reads like a shaped canvas as the focus is on a mostly, centrally located geometric composition that nearly fills the canvas as it pushes to the edges; feeling torqued and pushed to the square perimeter other angles emerge to break the tension and then, the suggestion perfected with carefully selected palettes and extreme color values providing strong contrasts between figure and ground.

Along with the confinement during covid came introspection and assessing oneself and career. Thus, the new parameters and perimeters of her paintings in 2021 and 2022 were a way for Trincere to hit reset and start with a fresh and “blank” canvas. The new imagery and corresponding titles are bold, full of moxy. Trincere was pulling from two sources for this work. First, the notion of resetting and starting at zero espoused by the Zero Group of Germany. They saw zero as “a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning”. More important, Trincere shared similar aesthetic philosophies with the Zero Group, emphasizing non-objective artwork focused on materials and an end game that was clean, reductive, and for the most part, de-emphasized the artist’s hand.3 The second source came from her own roots, the urban and punk bravado of the Lower East side of New York in the 1980s.4 She lived and her work expressed unapologetically the need to be non-conformist; avoiding trends and anything fashionable or popular, especially in art; and staying true to her guiding principles. Permission was not required, living on the edge was the norm, and attitude was everything—you like it or you don’t.

About Trincere’s Paintings:

In an interview in the publication Widewalls, Trincere discussed the influence that Neoplasticism had, along with the structured, reductive, geometric work of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg on her early paintings—strong vertical and horizontal lines, asymmetry, and reductive palettes all working together to create balanced and harmonic compositions.5

While her paintings remain true to those early influences and what she considers to be principles of non-objective painting, her shaped canvases were inspired by several unrelated factors. Formally, the work of Kenneth Noland and Leon Polk Smith from the 1970s influenced her compositions by achieving internal tensions, figure / ground relationships, structure, and determining the right perimeters. Specifically, Trincere noted Leon Polk Smith said: “you can use any two colors, as long as the proportion is right”.5 That statement guided many of her color selections and combining seemingly unrelated hues in non-traditional palettes. The second, and very big influence was the urban environment, living and working on the Lower East Side of New York City. The ever-present architecture, construction of new buildings, signage, and hurried life of the city delivered ready-

made geometric shapes for the taking. The origins of the “X” paintings in this exhibition came from the railroad crossing signs where she lived nearby, along with crosses, triangles, hexagons, and other shapes in street signs surrounding her every day in the city. Surfaces have always been a major focus for Trincere’s paintings. Inspired by her work with Yoshi Higa, a Japanese printmaker, she saw first-hand the dynamic process of loading ink on the surface of the lithography stone with every pore being obliterated when filled with ink and the resulting opaque forms were transferred to the paper.5 She translated that experience to building up the surfaces of her paintings with layer after layer of paint to remove the evidence of the warp and weft of the canvas. Her surfaces became flat and smooth with only variations in hues, the light and any corresponding reflection providing any indication of the surface receding or projecting off the painted surface. Later, she began incorporating metallic flakes and other additives to differentiate surfaces sheen among adjacent colors.

David Eichholtz

January 2023, New York

1 Email exchange between Li Trincere and David Eichholtz date January 4, 2023

2 Trincere, Li, Painting Zero, October 6-29, 2021, David Richard Gallery, https://davidrichardgallery.com/news/823-press-release-li-trincere-painting-zero

3 From: https://magazine.artland.com/art-movement-zero-group/

4 Conversation with Li Trincere, November 2022.

5 Rapid Movement, Tension and Weight - Li Trincere in an Interview, By: Brent Hallard, March 28, 2019, WIDEWALLS, https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/li-trincere-interview

LI TRINCERE

Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 1986 - 1990

Untitled (T03), 1990

Li Trincere

Untitled (T05) , 1990

Acrylic on canvas

Li Trincere

Untitled (T05) , 1990

Acrylic on canvas

Li Trincere

Untitled (T22) , 1987

Acrylic on canvas

Li Trincere

Untitled (T22) , 1987

Acrylic on canvas

LI-TRINCERE: HARD EDGY

By Peter FrankIn the reflexive history of late-modernist art, “hard-edge painting” persists as a broadly practiced style but eludes attempts to fix it in terms of meaning and context. At the time (and place) of its emergence, in New York at the end of the 1950s, hard-edge painting presented itself as an alternative to – and at the same time oblique variant of – abstract expressionism, and it directly prefigured minimalism, but it was neither of those. Rather than obscure or dissolve relational dynamics between formal elements, hard-edge painting re-valorized, even re-awoke, the notion of composition as a (perhaps the) prime factor in the formulation of artwork. It was not simply the image that was determined by formal relations, but the painting as an integral object – a concept literalized by hardedge work incorporating shaped canvas.

Hard-edge – including shaped-canvas – painting flourished as a recognized “movement” (or two) in the first half of the ‘60s, but had emerged earlier in the evolution of individual artists associated with the tendency (e.g. Ellsworth Kelly, Leon Polk Smith, Jack Youngerman) and connected quite openly with modalities of geometric abstraction that went back to the 1910s. Hard-edge painting, an American manifestation, was in dialogue to some extent with its postwar European counterparts, but looked more to earlier loci such as the Bauhaus, de Stijl, Cercle et Carré, and other post-cubist phenomena. Hard-edge painting carried over the formal clarity and vibrant color of these high-modernist movements but eased the brittle counterpoint of cubist-derived composition into an articulation of field rather than of form – or, more to the point, field as form.

The elusiveness of hard-edge painting results in no small part from its transitional nature as an historical style, bridging the mega-movements of abstract expressionism and minimalism. But the continuing appeal of hard-edge practice, which has resulted in its stubborn recrudescence in various American art centers over the last two-thirds of a century, also makes it a difficult “ism” to package (especially as a “wasm”). And yet, hard-edge abstraction endures, presenting and re-presenting itself as an alternative to whatever kind of abstraction, or painting in general, might be in vogue at any given time, in any given place.

Having emerged around 1980 and having persisted in her hard-edge approach up until today, Li-Trincere demonstrates both the diffidence and the appeal of the hard edge. Trincere is dedicated to the practice almost ideologically, regarding it as an outgrowth, even shaper, of personal lifestyle and intellectual/poetic inquiry. Her commitment to a formal language of bold, crisply articulated form, vibrant color, and a compositional sense that conflates the monumental with the dynamic, the formidable with the fragmented, has held steady throughout her career. What Trincere has sought unstintingly has been an expression of the urban environment, refined into a visual language that celebrates modern life as an optical ecology of urgent signage and irrepressible kinesis. Beauty for Trincere is energy, and vice versa.

Clearly, the ethos as well as (perhaps even more than) the aesthetic of Trincere’s art harks back to Italian Futurism. (Compare her recent jagged, serialized works to the post-World War I abstractions of Giacomo Balla, for instance, or the proto-Art Deco images of Fortunato Depero.) The parallel here, however, is more one of attitude than of manner. At the time of Trincere’s emergence the Futurists’ tough, streetwise stance had been revived by Punk, a social as well as musical phenomenon with which Trincere, and the circle of artists she associated with in the 1980s, strongly Identified. They considered their flat, roughly architectural, picture-plane-adhering approach as, perhaps literally, emblematic of city life and social alienation. Theirs was a tough abstraction, easy to read but commanding respect for its intricacy as well as for its presence.

Note that Trincere and her circle – including painters such as Ted Stamm, Alan Uglow, Steven Parrino, Olivier Mosset, and Mary Obering – were active at a time when another kind of geometric strategy was attracting attention. The “neo-geo” of artists such as Peter Halley, Peter Nagy, and Ashley Bickerton came out of conceptual art and structuralist and post-structuralist theory, proposing in effect a non-objective version of what is now called the “pictures generation.” Trincere and her friends preferred a neo-modernist tack, oppositional, dramatic, and devoted to rather than dismissive of visual pleasure. It would seem ironic that these Punk-inspired painters would leave the nihilism to their cooler contemporaries; but, as their practice evinced, Punk itself, born of furious alienation and delirious cameraderie, was anything but nihilistic.

Was – and is – Trincere’s aesthetic, then, “re-geo”? Has it over-relied on the valorizing context(s) of the geometric art movements and painters that have influenced and prefigured her? Relied, yes; over-relied, no. Even as she professes the direct influence of Leon Polk Smith and Frank Stella, among others, Trincere adds to the vocabulary of envisionment she inherited from them and their modernist forebears. She is no mere revivalist, having formulated her style four decades ago and evolved, elaborated upon, and experimented with it consistently ever since. The earmarks of Trincere’s relational geometries readily distinguish hers from anyone else’s, even as they readily display her artistic heritage. Practicing an aggressively non-neutral aesthetic, she reasserts the geometric image, flag-like, as a declaration of presence and at the same time a site of visual gratification. Li-Trincere is not and has not been alone in her proud adherence to neo-modernist plastic values. But she is notable for the fervor of that adherence, and for the stunning structures that have long emerged from that fervor.

Los Angeles

January 2023

LI TRINCERE

Hard Edge, Geometric Paintings: 2021 - 2022

You Woke Up the Beast , 2021

Untitled

Caren

20.25

About Li Trincere:

Li Trincere lives and works in New York City. She has exhibited her artworks in the United States and abroad since 1982. Born in Far Rockaway, Queens she moved to Manhattan in the early 1980s, settled in East Village, and was part of that important development of abstract painting in Lower Manhattan. Trincere exhibited along with her colleagues Olivier Mosset and Alan Uglow at the Mission Gallery run by D.D. Chapin in 1984 and 85, then with the influential and important Julian Pretto Gallery. In 1989 and 1990 her work was presented in solo exhibitions at Galerie Rolf Ricke in Köln. More recently, Trincere exhibited at Minus Space in Brooklyn. David Richard Gallery is pleased to represent Li Trincere.