24 minute read

Dutchess County Women in the Military

By Nan Fogel

Nan Fogel' s interests in history and the arts have led to articles in past Year Books. She serves on the Publications Committee of the Historical Society and currently edits the Newsletter. She works at Vassar College.

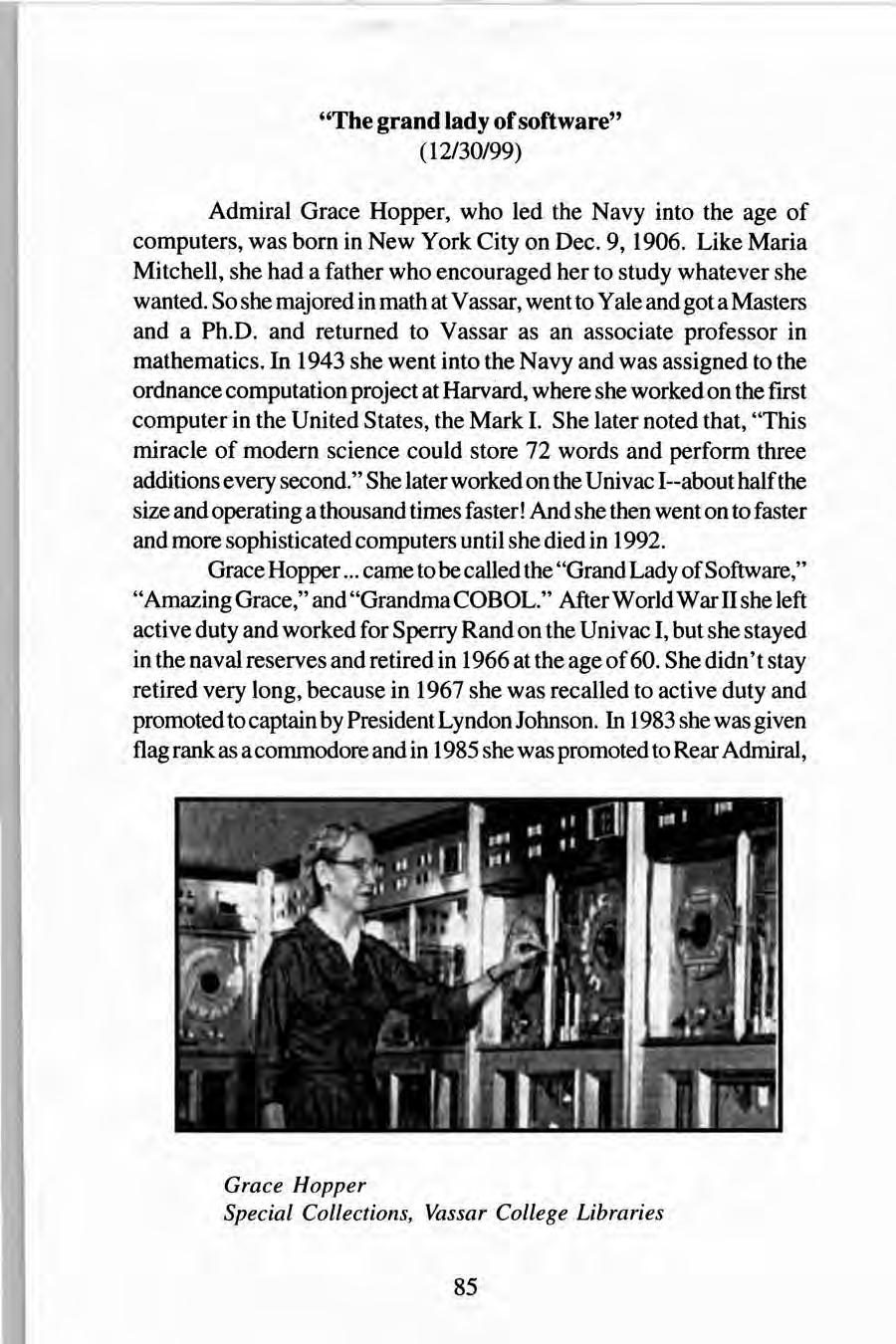

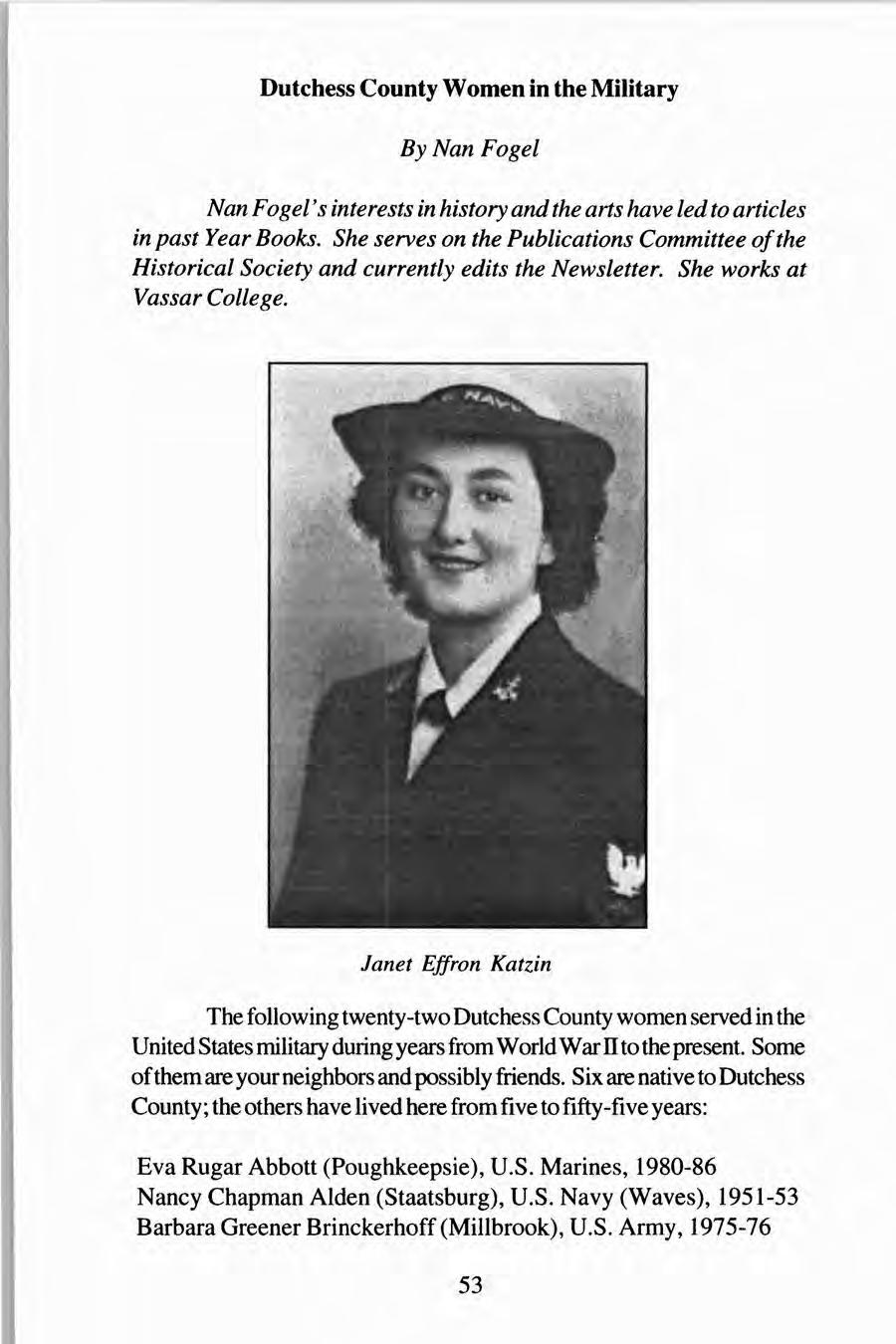

Janet Effron Katzin

The following twenty-two Dutchess County women served in the United States military during years from World War II to the present. Some of them are your neighbors and possibly friends. Six are native to Dutchess County;theothershavelivedherefromfivetofifty-fiveyears:

Eva Rugar Abbott (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Marines, 1980-86 Nancy Chapman Alden (Staatsburg), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1951-53 Barbara Greener Brinckerhoff (Millbrook), U.S. Army, 1975-76

Patty Brunk (Dover Plains), U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, 1978-84 and Air Force National Guard, 1997-present Karen Joyce Buckley (Hyde Park), U.S. Navy, 1978-82 and Naval Reserves, 1991-present Dorothy HammerleButrica(Fishkill), U.S. Marines, 1953-54 Lorraine Mondrick Campilli (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Army Medical Specialists Corps, 1954-56 Mary Darrow Ciolko (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1944-46 Helen Salsick Curran (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Army Nurse Corps, 1942-46 and U.S. Army Reserves, 1946-52 Patricia Deufemia (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Air Force, 1980-95 Elva Riker Girton (Wappingers Falls), U.S. Army, 1964-66 Goldie Weiss Greene (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Army Nurse Corps, 1943-46 Evelia Gary Harrell (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Army, 1956-58 Mary Alice Hunter(Poughkeepsie), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1943-46 Judy Utecht Husted (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Navy, 1979-82 Janet Effron Katzin(Litchfield, CT), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1943-45 Alice Roy LaDue (Fishkill), U.S. Army Medical Unit, 1945-46 Sarah Poppinhouse (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Army, 1975-78 Sally Goldberg Reifler (Wappingers Falls), U.S. Army Nurse Corps, 1944-46 Martha Umphenour Rooney (Columbia, SC), U.S. Army Nurse Corps, 1960-63 Margaret Stickler Schultz (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1943-45 Marjorie Weatherwax Woodside (Poughkeepsie), U.S. Navy (Waves), 1943-45

Collectively, the women served in every decade from the 1940' s to the 1990' s, years that cover World War II, the Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf wars. All branches of service are represented with the exception of the Coast Guard. Unfortunately it was not possible to find a woman veteran from Vietnam who was willing to be interviewed. Letters were sent to approximately 150 women whose names were gathered from bus lists of those who had gone to Washington, DC to take part in the dedication of a memorial to women who have served in the military, referrals from women in the American Legion and Castle Point Veterans Hospital, and word of mouth. An article in the Poughkeepsie

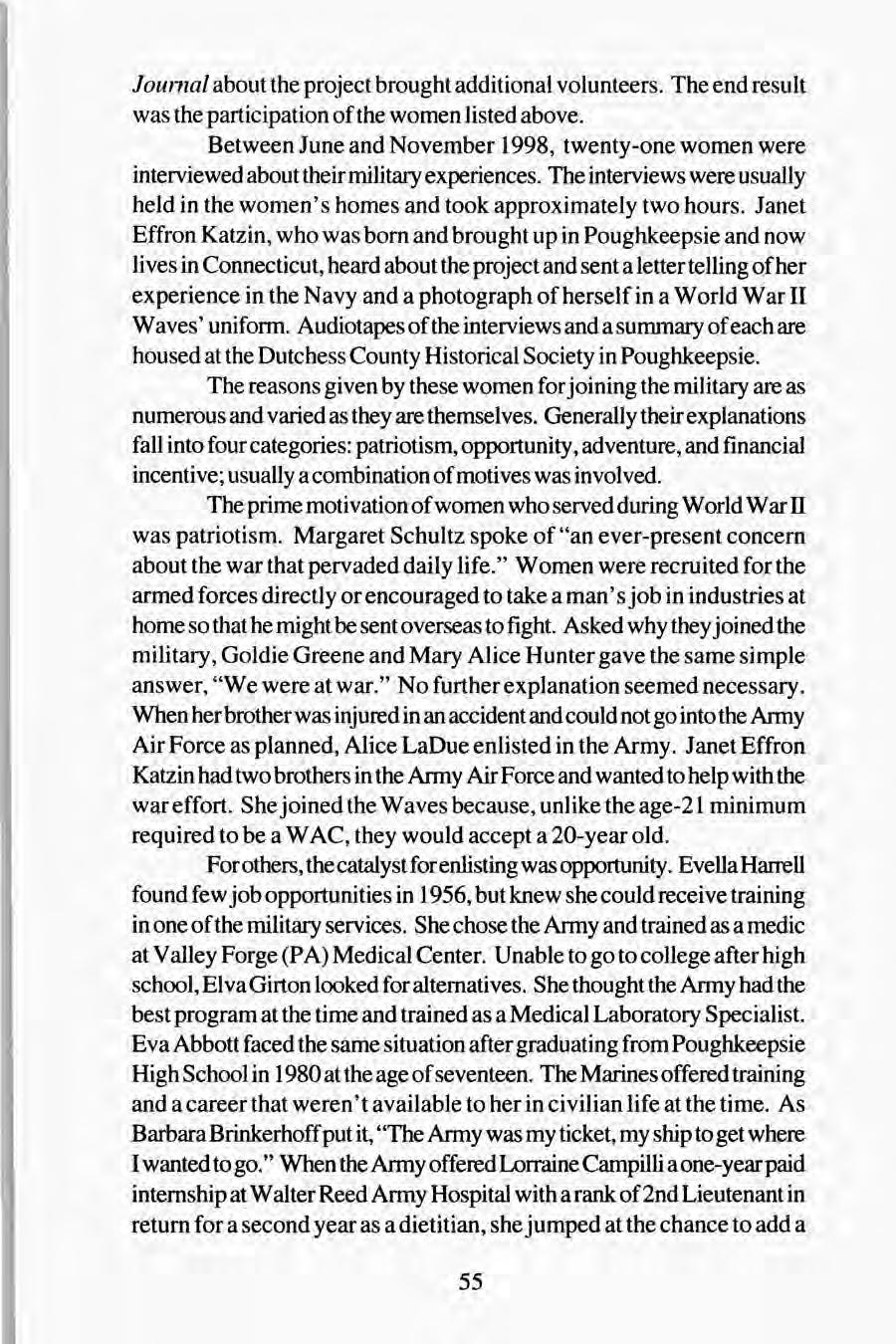

Joumal about the project brought additional volunteers. The end result was the participation of the women listed above. Between June and November 1998, twenty-one women were interviewed about their military experiences. The interviews were usually held in the women's homes and took approximately two hours. Janet Effron Katzin, who was born and brought up in Poughkeepsie and now lives in Connecticut, heard about the project and sent a letter telling of her experience in the Navy and a photograph of herself in a World War II Waves' uniform. Audiotapes of the interviews and a summary of each are housed at the Dutchess County Historical Society in Poughkeepsie. The reasons given by these women for joining the military are as numerous and varied as they are themselves. Generally their explanations fall into four categories: patriotism, opportunity, adventure, and financial incentive; usually a combination of motives was involved. The prime motivation of women who served during World War II was patriotism. Margaret Schultz spoke of "an ever-present concern about the war that pervaded daily life." Women were recruited for the armed forces directly or encouraged to take a man's job in industries at home so that he might be sent overseas to fight. Asked why they joined the military, Goldie Greene and Mary Alice Hunter gave the same simple answer, "We were at war." No further explanation seemed necessary. When her brother was injured in an accident and could not go into the Army Air Force as planned, Alice LaDue enlisted in the Army. Janet Effron Katzin had two brothers in the Army Air Force and wanted to help with the war effort. She joined the Waves because, unlike the age-21 minimum required to be a WAC, they would accept a 20-year old. For others, the catalyst for enlisting was opportunity. Evelia Harrell found few job opportunities in 1956, but knew she could receive training in one of the military services. She chose the Army and trained as a medic at Valley Forge (PA) Medical Center. Unable to go to college after high school, Elva Girton looked for alternatives. She thought the Army had the best program at the time and trained as a Medical Laboratory Specialist. Eva Abbott faced the same situation after graduating from Poughkeepsie High School in 1980 at the age of seventeen. The Marines offered training and a career that weren't available to her in civilian life at the time. As Barbara Brinkerhoff put it, "The Army was my ticket, my ship to get where I wanted to go." When the Army offered Lorraine Campilli a one-year paid internship at Walter Reed Army Hospital with a rank of 2nd Lieutenant in return for a second year as a dietitian, she jumped at the chance to add a

fifth year to her B.S. degree from Penn State University and be relieved of another year without an income. For Judy Husted, the Navy offered education, travel, and the chance to meet new people. Her training in electronics took almost half her time in service. The call to adventure spurred some to enlist. Nancy Alden wanted "to do something new and adventurous." As a journalism student and editor of her paper at Winthrop State College for Women in South Carolina, she thought she could always go back home and be a journalist one day. For Sarah Poppinhouse it was a desire to see the world.

Financial considerations were never entirely absent from the decision to enlist, although they were only part of the reason the women joined the military. With the financial assistance she received as a member of the Marine Corps Reserves from 1978-1984, Patty Brunk was able to finish college. She graduated fromMarist College with a Master's degree in psychology; with further study she earned an advanced certificate in school psychology. Martha Rooney and her twin sister joined the Army Reserves while they were in a three-year nursing school program in Kansas because they liked the idea of being paid and wanted to buy a car. It may have been a light decision but it was one she never regretted. In the Army Nurse Corps she was given more responsibility and a greater variety of nursing experience than she would have received as a civilian. That, together with meeting her husband and wonderful friends, has made her wonder what her life would have been like if she and her sister had not wanted that car so badly. Basic Training lasted from four to twelve weeks, depending on the branch of service and the needs of the country at the time. Some women took it in stride, but for others it was a harrowing experience. Margaret Schultz said the discipline didn't bother her. "I had made up my mind before enlisting that I would be given orders and I would follow them." Karen Buckley called her experience of basic training "deliberately hard" at the Navy base in Orlando, Florida. "All along we were tested as to whether we could take authority without question. I didn't rebel against it but some couldn't do that. We lost a lot of girls that way." Probably Mary Ciolko had the easiest time. On her way to Hunter College in New York City, where training was to be held, she learned about the Waves Chorus. She was accepted after auditioning and sang in the chorus at Navy hospitals and at official public functions. Although it only lasted during the training period, Ciolko said it relieved her of some of the

more unpleasant duties. Patty Brunk spoke of the pride she felt when she finished basic training at Parris Island and brought her 84-year old grandmother to South Carolina for her graduation. "I felt better than I had ever felt, both physically and mentally." "I went in as a child," Barbara Brinckerhoff said, relating a punishment she received on her first day ofbasic training in the Army at Fort McClellan, Alabama. "It was a valuable lesson. I learned to keep my mouth shut and my eyes and ears open." For Eva Abbott, the twelve-week Marine training program at Parris Island was "emotionally tough." She spoke of a process of breaking down individual will in order to foster being part of a team in which each person helped others toward a common goal. "We learned to depend on each other and the discipline was very strict." For her the experience was transforming. "I went into the Marines with little confidence," she said. "After boot camp I knew I could do anything." The work the women did was interesting and often vital. Assignments depended on preferences, as well as the results of aptitude tests, education, previous work experience, and current military needs. Women who served as nurses entered service already trained. Helen Curran joined the Army Nurse Corps in March 1942 and was sent to Iran as part of the Persian Gulf Company. Units stationed there were involved in the effort to supply Russia with planes, fuel and food. She served in four different hospitals along the supply route, often in desert conditions, where temperatures were between 120 and 150 degrees F. As an Army nurse, Goldie Greene worked in a large general hospital near Oxford, England which had been set up to receive injured American soldiers from battlefields in Belgium and France. She was there during the D-Day invasion. A year later, in June 1945, she was sent to Frankfort, Germany to nurse American soldiers needing long recoveries before being sent home. When Sally Reifler graduated from a five-year nursing program at Simmons College in 1944, she enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps. She was part of the 221 st General Hospital Unit stationed in Challons-sur-Marne, France, where wounded soldiers were sent after the Battle of the Bulge and other fighting during the last months ofW orld War II. In the early 1960' s, Martha Rooney was assigned to two 75-bed medical wards in Fort Bragg's new 800-bed hospital. During the Cuban Missile Emergency in October 1962 her unit was put on red alert and told to be ready to leave at a moment's notice. Fortunately the crisis passed and she remained at the North Carolina base. Other women involved in medical work received their training after

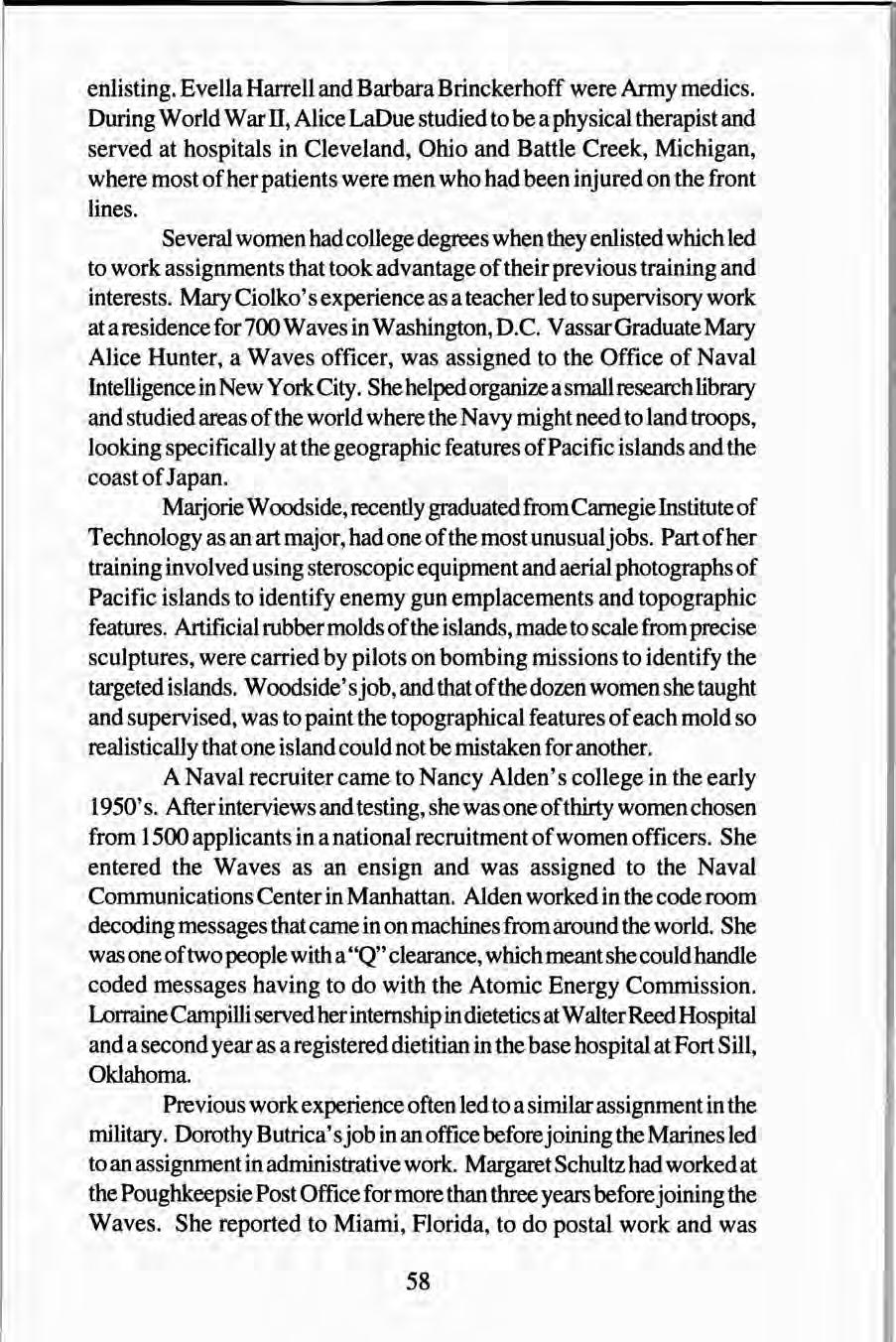

enlisting. Evella Harrell and Barbara Brinckerhoff were Army medics. During World War II, Alice LaDue studied to be a physical therapist and served at hospitals in Cleveland, Ohio and Battle Creek, Michigan, where most of her patients were men who had been injured on the front lines.

Several women had college degrees when they enlisted which led to work assignments that took advantage of their previous training and interests. Mary Ciolko' s experience as a teacher led to supervisory work at a residence for 700 Waves in Washington, D.C. V assarGraduate Mary Alice Hunter, a Waves officer, was assigned to the Office of Naval Intelligence in New York City. She helped organize a small research library and studied areas of the world where the Navy might need to land troops, looking specifically at the geographic features of Pacific islands and the coast of Japan. Marjorie Woodside, recently graduated from Carnegie Institute of Technology as an art major, had one of the most unusual jobs. Part of her training involved using steroscopic equipment and aerial photographs of Pacific islands to identify enemy gun emplacements and topographic features. Artificial rubber molds of the islands, made to scale from precise sculptures, were carried by pilots on bombing missions to identify the targeted islands. Woodside' s job, and that of the dozen women she taught and supervised, was to paint the topographical features of each mold so realistically that one island could not be mistaken for another. A Na val recruiter came to Nancy Alden's college in the early 1950' s. After interviews and testing, she was one of thirty women chosen from 1500 applicants in a national recruitment of women officers. She entered the Waves as an ensign and was assigned to the Naval Communications Center in Manhattan. Alden worked in the code room decoding messages that came in on machines from around the world. She was one of two people with a "Q" clearance, which meant she could handle coded messages having to do with the Atomic Energy Commission. Lorraine Campilli served her internship in dietetics at Walter Reed Hospital and a second year as a registered dietitian in the base hospital at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Previous work experience often led to a similar assignment in the military. Dorothy Butrica' s job in an office before joining the Marines led to an assignment in administrative work. Margaret Schultz had worked at the Poughkeepsie Post Office for more than three years before joining the Waves. She reported to Miami, Florida, to do postal work and was

promoted rapidly. In September 1944, she was sent to Officers' Candidate School. After completing the program she took a new assignment in Washington, D.C., also in postal work, as a supervisor reporting to a Lieutenant Commander. Sometimes it was high marks on tests that determined what a woman would do in the military. Elva Girton did so well she was able to train as a medical laboratory specialist. At the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology she did blood work, renal analyses, and prepared slides of human tissue specimens sent to the Institute from around the world. High scores qualified Sarah Poppinhouse for intelligence work. After six months of training she was sent to Okinawa where she intercepted and decoded messages in Morse code. Judy Husted' s test scores allowed her to enter the non-traditional (for women) field of radar and electronics. She was the first woman to work as an electronics technician on cryptographic equipment. With top security clearance, she diagnosed, repaired and maintained the machines in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington, D.C. More fields opened to women across the service branches in the late 1970' sand early '80' s. Patricia Deufemia, an officer in the Air Force, volunteered for the job of Section Commander, a new job category open to women officers. For the next two years she was in charge of the military behavior and discipline of 550 men who repaired and maintained C 130 planes. In her first year on the job she discharged 110 men for behavioral or drug problems. "It wasn't hard," she said, "because lives were on the line. The men who flew the planes had to know they were trustworthy." She went on to do a "remote tour" in Korea in 1986, acting as protocol officer at Ossan Air Base, outside of Seoul. In order to move ahead, Deufemia changed jobs every two or three years during her fifteen years in the Air Force. Patty Brunk chose avionics, a technical job involving repair and maintenance of a plane's electrical and electronic systems when she joined the Air Force National Guard in 1997. It is definitely a non-traditional job for women but Brunk says she enjoys being in a male-dominated field. She knows she is doing important work in meeting the high standards that are required for a craft's safety. When Eva Abbott chose a job in the aircraft maintenance field she was the only woman in the shop. She felt she had to work harder than anyone else to prove herself. Her work involved packing emergency materials: parachutes, life rafts, oxygen regulators and seat pads. She advanced to become an inspector and trained others.

Most of the women felt they were treated fairly in the military and there were few reports of discrimination. During World War II many women entered as officers in the Army Nurse Corps or the Waves. They were doing vital work and were well respected. Marjorie Woodside thought that was generally true of women officers. As Goldie Greene put it, "Being an officer excused the fact that I was female." Mary Alice Hunter, a Wave officer, did the same intelligence work as the men in her department. Mary Ciolko thought she remembered some opposition to bringing women into the Navy before the Waves program began during World War Il, and supposed "it was because it was a men's club." She stressed the fact that Waves were volunteers (the name stands for Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) and that their involvement in the war effort was considered commendable. Looking back at her experience in the military, Margaret Schultz said she didn't remember any discrimination and it would seem her promotions and appointment to Officers' Candidate School were proof of it. She thought the war years brought the beginnings of feminism. "A lot of women liked working and not having to depend on their husbands for everything," she recalled. Several women who did not experience discrimination themselves said they saw instances of racial prejudice. During the 1950' s Evella Harrell said she did not feel discriminated against as a woman, but the town near her training base in Alabama was segregated. When she and others in her company went to town they had to go in separate groups of blacks and whites. Janet Katzin said the Navy was segregated during World War II, as were the other branches of service; she recalled separate units of black men at the Great Lakes Training Center. When Elva Girton joined the Army in the mid-1960' s she felt the low enlistment of women was due to their being steered into clerical work. High test scores gave her a choice of occupation. She credits the lack of discrimination to the intelligence of people she worked with in medical technology. Working as an aircraft specialist in the Navy, Karen Buckley was twice denied training for a higher level technical job on grounds that "there were already too many women in that field." At the time she served ( 1978-82), women were not allowed on aircraft carriers; on the other hand she was the first woman to qualify for plane captain in her squadron. Buckley thinks things began to change in the 1970s and '80s as the military establishment became more sensitive to the women in its ranks.

A year after Sarah Poppinhouse enlisted in the Army in 197 5, the process of integrating men and women began. She went through basic training in an all-female unit; a year later men and women trained together. "In trying to make it equal," she said, "things were sometimes carrried too far. Common sense was missing." Throughout her time in the Navy, when she was the first or only woman in a job category, Judy Husted felt she was treated fairly. Her teachers, peers and the men she worked with were always helpful and respectful. She atttributes it to the intelligence of people required to meet the high standards of work in her field of electronics. Two women reported an incident of sexual harassment. A third felt she had to take care of herself a lot and wasn't always sure of her rights. "Nowadays," she said, "women don't have to worry about protecting themselves as much or knowing their rights. It's built into the military structure." Without exception these women had positive things to say about their time in the military. The desire to serve their country as well as their dreams of travel and adventure seem to have been realized. It's hard to convey in print the emotion in Mary Alice Hunter's voice when asked if she was glad to have had her experience in the Waves during World War II. "Oh, yes," she said. "OH, YES! Very, very glad." Other voices echo her response: "It was the greatest thing, I wouldn't have traded it for the world." ( Goldie Greene) "I enjoyed it all, the training, the work, the people, even the discipline." (Alice LaDue) "The military gave me a foundation for believing in myself." (Karen Buckley) "It taught me I could take care of myself." (Lorraine Campilli) "Going into the Marines was one of the best decisions I ever made." (Eva Abbott) "I liked coming into my own. People took me as I was; anything I accomplished was my own." (Judy Husted) Over and over again, the women named increased pride, confidence and independence as the fruits of their military experience. Other benefits were the occupational opportunities and excellent training that saw many of them into careers when they left service. One of the most valuable lessons the women named was learning to get along with a wide variety of people. Others mentioned learning more about the world. Not surprisingly, they named friendships as a positive outcome of service.

Many are still in touch with one or more people they met in service, even those who served more than fifty years ago. All agreed things have changed for women entering military service now. Most often mentioned were rules about pregnancy and new opportunities for women. When Nancy Alden was in the Navy in 1951-53, the highest ranked woman was a captain. At the dedication of the Women's Memorial she saw women majors, colonels and lieutenant colonels, several pushing baby carriages. "That's very different from my time," she said. "Then, even highly-trained women had to leave service if they were pregnant. Now a woman can build a career in the military." The rule was still in effect in 1963 when Martha Rooney chose to leave the Army, though she would have preferred to stay, because she and her husband wanted to have children. By the 1980s things had changed. Eva Abbott had her two children while she was still active in the Marines. When she left service in 1986 women no longer had a choice about staying in when they were pregnant. Now they have to remain for the length of their commitment. Pat Deufemia said a lot more job categories were opened to women when she joined the Air Force in 1980 and there are even more now. "In the 1980' s a male chauvinist attitude prevailed. Women had to prove themselves. Now they are on the front lines and flying." Eva Abbott agreed there are many more jobs open to women now, even some that could put them in combat zones. Among our interviewees, Eva Abbott (aircrew survival equipment), Patty Brunk (avionics), Judy Husted (electronics), and Pat Deufemia ( as a section commander), were all in jobs newly opened to women at the time they served. After military service, the women in our group who served during World War II and the Korean War period, tended to marry and have large families. Many continued to work. Helen Curran, Goldie Greene and Martha Rooney all have long histories in nursing. Lorraine Campilli and Evella Harrell stayed in health fields for many years as well. Nancy Alden became an elementary school teacher, a town supervisor and a journalist, the career she originally prepared for in college. Long before the women's movement took hold in the 1960' s, many of these women combined raising families and working outside the home. Those who served after 1965 continued to work after being discharged, but families were smaller, one or two children generally, and divorce was more common. Often they sought more education, as Sarah Poppinhouse

did, using the G .I. Bill to go back to college and get a degree in computer science. Although the women who served in the 1980' sand '90' shad more career opportunities open to them while in service, it didn't always have positive results when they returned to civilian life. Eva Abbott was surprised to find employers here did not consider her time in the Marines as work experience. The job she had done in the military was not the work she applied for but she had developed attitudes and skills that are critical for the workplace: discipline, responsibility, meticulous attention to detail. She was the mother of two daughters, had lived for extended periods in two foreign countries, and her leadership abilities were evident from support group activities at the air base in Cherry Point, North Carolina. Judy Husted said it was in civilian life that she found discrimination against her. Trained to diagnose, repair and maintain sophisticated electronic equipment, Husted said she was laughed at when she returned to Dutchess County and applied for jobs in her field. ''They said no woman had ever applied for a job taking care of electronic equipment. I didn't hear back from them." Husted went to school at night and now works as a computer programmer. The Women's Memorial in Washington, D.C. was dedicated in October 1997. It is located at the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery and honors the nearly two million women who have served their country in the past two hundred years. The museum holds a computerized register of women who served in the military and documents their experience and stories. Four of our interviewees went to the dedication. From their descriptions, images emerge of several thousand women from all over the country meeting in the nation's capital to celebrate women's military service to the country. The ceremonies included speeches by Vice President Gore, General Wilma Voight, whose idea it had been to build the Memorial, and a 100-year old woman who had served two years as a Navy yeoman before World War II. There was a large parade, many speeches, and receptions and reunions all over the city. The most impressive part of the weekend to Martha Rooney, who attended with her twin sister, was the mile-long line of women, each carrying a small battery-operated candle, marching by branch of service from Lincoln Memorial across the bridge to the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery. Sally Reifler, the local representative of Women In Military Service for America (WIMSA), called it "a wonderful experience." She went with her daughter and saw

several women she'd known in the Anny Nurse Corps during World War II. Nancy Alden also went with one of her daughters, who is in the Reserves. Elva Girton called the dedication "an emotional time." Although her foot was in a cast and she had to be pushed in a wheelchair by a friend, Girton said it didn't dampen her spirits. Whether they had gone to the dedication or not, all the women who were interviewed spoke of the pride they felt in women's contributions being recognized. As one woman said, "It was a long time coming." It was a pleasure to talk with these women and to live vicariously through them over six decades in the military. Those who served in World War II recalled forgotten memories: blackout shades and rationing, men and women spotting planes for Civil Defense, crowded railroad stations and trains, and servicemen everywhere. Women who spoke of "going to places they never expected to see," i.e. Chicago and Washington, D.C., recalled how little the average person traveled outside home areas in those days. Goldie Greene, who served in the Army Nurse Corps during World War II, spoke of medical advances at that time: skin grafts on bum patients, new methods of giving blood transfusions on the battlefields, and the "big panacea," penicillin. Greene described the method: "We filled a large syringe and gave shot after shot from it, discarding needles and inserting new ones for each patient. No one now would think of giving it to anyone the way we did then." Some methods of gathering intelligence then seem naive compared to today. In the small research library at the Office ofN aval Intelligence that Mary Alice Hunter helped organize to gather information about the Far East, some of the material that flowed into it were photo albums of people who had traveled there. Margaret Schultz emphasized the importance of mail to servicemen and recalled it had the same priority as food. 'There was a lot of secrecy surrounding the mails then because it could give the enemy advance information about where troops were being sent." In the decades that followed, women made inroads in all branches of the military. The division between "men's work" and "women's work" broke down and women rose to opportunities to enter new fields and prove themselves worthy. Who can gauge the impact on women ofleaving the familiarity and safety of home to travel to distant bases and cities for exhausting training and work? Or imagine the effects of thousands of interactions with people from all parts of the country and world, or know the pride they felt in their new

independence and accomplishments? It may well have been, as Margaret Shultz said, "the beginning of feminism." Adventurous, patriotic, resourceful, bright --all of these qualities and more describe the women in this article. They deserve a salute.