Deakin University is known for its collection of sculpture by well established artists. This valued and significant collection includes works by sculptors such as Geoffrey Bartlett, Inge King, Bruce Armstrong, Margel Hinder and Peter Blizzard. There is also a growing collection of small sculpture within the University’s holdings. Since 2009 the University has organised an annual Contemporary Small Sculpture Award which attracts both national and international entries. This acquisitive award has seen the addition of many small sculptures to the University’s collection from a diverse group of artists such as Dadang Christanto, Stephen Benwell, Mikala Dwyer and Lisa Roet.

This exhibition, exploring the sculptures of Andrew Rogers, Evolution: From Maquettes to Major Sculptures 1996-2019, enhances our understanding of how sculpture can work on a smaller scale or be a study for a larger work, something the University’s Contemporary Small Sculpture Award explores each year.

As a significant sculptor with an international profile who is based in Melbourne, it is important that Andrew Rogers’ work and career be suitably acknowledged. A prolific sculptor, his work in this exhibition is a tantalising array of bronze, stainless steel and polyamide and is both lyrical and enchanting, exploring the interplay between the nature and formality of the object. Andrew has generously supported the development of the exhibition with the loan of many works from his private collection to enable the visitor to see the genesis of an idea translated to a large scale.

After over 20 years in the arts industry I have had the privilege to meet and work with a range of gifted artists and I am so grateful that one of them is Andrew Rogers. I trust you will enjoy the opportunity to explore the work of this internationally respected and talented artist.

Leanne Willis Senior Manager, Art Collection and GalleriesThe work of few, if any, contemporary Australian artists has received the same international exposure – in terms of site-specific commissions, exhibitions, documentary films and substantial publications – as that of Melbournebased Andrew Rogers. But it would be fair to say that this critical attention has focused largely on the achievement for which the artist is best-known: the transnational series of colossal and remotely-located land-art projects known as geoglyphs.

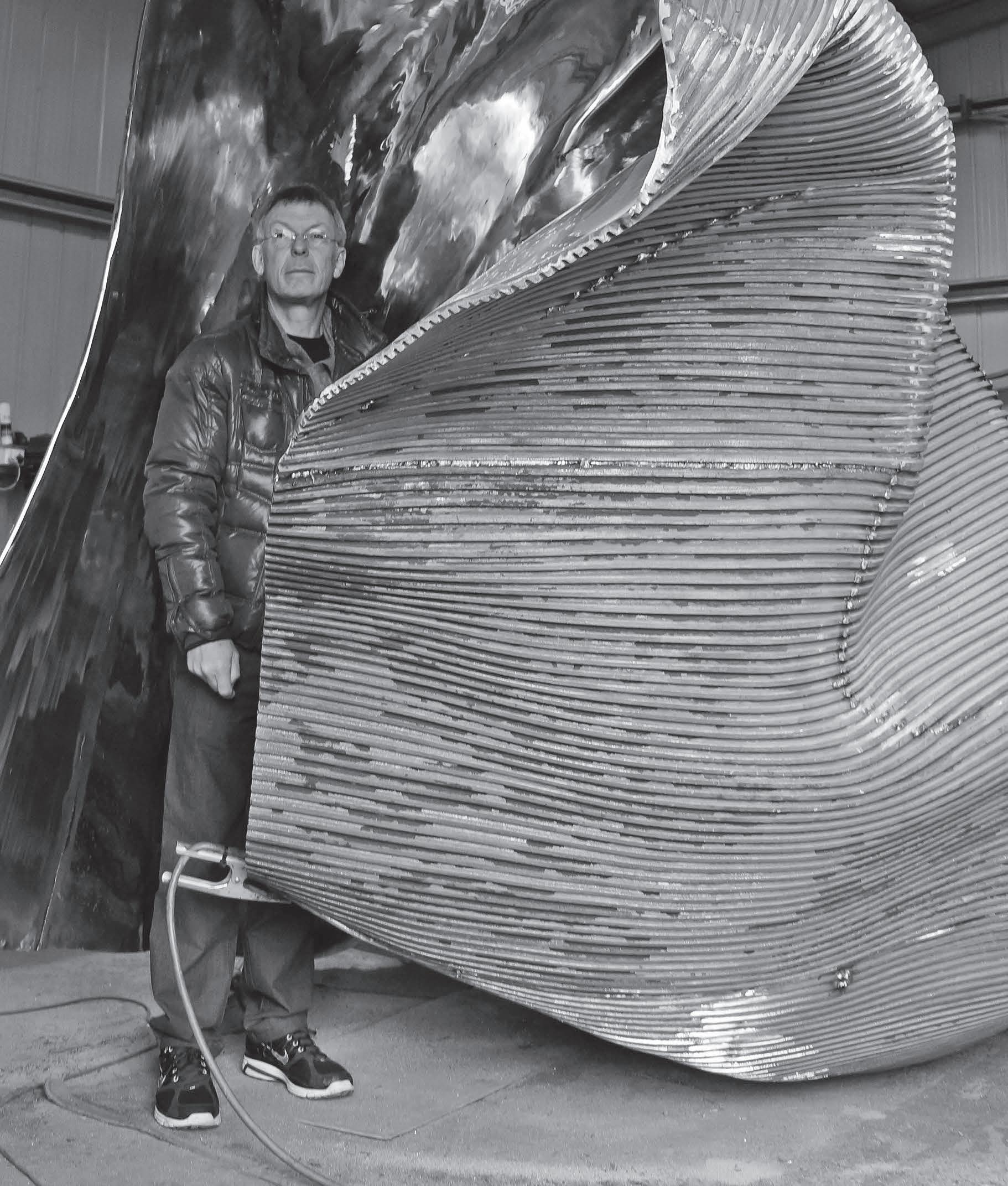

By and large, it has been the breathtaking scale, conceptual originality and eye-wateringly complex logistics of these projects that have been the subject of the aforementioned commentary. This is not to suggest, however, that the artist’s repertoire of largescale autonomous sculpture hasn’t had its share of attention with critical coverage, as has been the case, in international journals and the mainstream press.

All the better therefore that here, now, with this Deakin University Art Gallery exhibition, we have a specific and comprehensive focus on the artist’s considerable corpus of maquettes whose production has been a mainstay of Rogers’s practice for several decades. In recent years, a selection of these comparatively small-scale and yet highly-finished works has found its way into prominent public collections, most notably those of the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria, as well as the Geelong Gallery in regional Victoria, the Ian Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne, the McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, the Akureyri Art Museum in Iceland, the Australian Consulate in Japan, Gibbs Farm Collection in New Zealand and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. In this last instance, the maquettes were those for the first three geoglyphs created in 1998 in Israel’s Arava Desert at the outset of the so-named ‘Rhythms of Life’ land art project.

Before turning to focus on the main theme of this essay – the important body of work represented by Rogers’s maquettes made from around 2015 to the present – it is worth pausing for a brief review of signal developments in the artist’s oeuvre before this timeframe.

These developments have been extensively discussed in various exhibition catalogues and two handsome, heavyweight monographs: the first by Eleanor Heartney and titled Andrew Rogers, Geoglyphs, Rhythms of Life (Edizione Charta, 2009) and the more recent by Silvia Langen titled Andrew Rogers, Rhythms of Life, A Global Land Art Project (Prestel, 2015). Similarly, the catalogue of a previous exhibition of Rogers’s earlier maquettes (A Retrospective: Maquettes: 1996–2015) held in 2015 at the McClelland Gallery and Sculpture Park offered a succinct outline by Frances Lindsay of the artist’s early creative interests (painting and music) and specific influences on his sculpture (Rodin, Moore, Smith and Caro). Lindsay also discusses the underlying philosophy of the artist’s practice noting that ‘belief in the individual as a catalyst for change informs Rogers’s ongoing practice’, quoting the artist’s conviction that “We are all individuals possessing the sanctity of a singular life and the ability to express ourselves. At the same time, we are part of the society within which we live...(thus) figurative forms …remind us that it is the individual that makes our world a place of justice and compassion.”

Such philosophical underpinnings to Rogers’s practice are explored more fully in Lindsay’s essay than is possible or necessary to do here. By the same token, Lindsay traces in more detail than l propose to do, the artist’s experimentation with different media (bronze, polyamide, stainless steel) as well as the overall compositional shifts in Rogers’s sculpture from the organic simplicity and lush curvilinear character of early sculptures such as Leading (1996) and Rhythms of Life (1996) through an increasing complexity of structure in works such as Growth (1999) and Living (1999) where a kind of aerial anarchy inhabits tall, skeletal forms with swaying axes and cascades of cusp-like elements within a profile suggestive of a wayward molecular model.

These works are followed by a series of more angular or planar forms such as Ripening (1999), Escalate (2001) and the beginnings of a long sequence of supple, ribbed and twisting forms identified by the umbrella title of Rise (2000–2015). Overall, the visual dynamic, gravity-defying inferences and tactile quality of these works evoke the essential character of Rogers’s art which is an elusive but vital presence.

Impressively, all this artistic exploration occurs in parallel with Rogers’s other career in business which necessitated constant international travel that, in turn, furnished important opportunities such as the artist’s seminal experience of being able to handle Rodin’s casts and small sculptures in the basement of the Musée Rodin in Paris – a moment described by Lindsay as ‘an epiphany that changed the direction of his life.’

Moving on from Lindsay’s commentary, l’d now like to address the more recent maquettes and to do so in the context of a few broad themes: the significance

and purpose of a maquette; the ways in which certain artists, like Andrew Rogers, have sought primarily to communicate – in maquettes and scaled-up works alike – a sense of rhythmic and sometimes dramatic motion albeit within a static (sculptural) composition; analogous examples of sculpture by Tony Cragg and Naum Gabo; and finally, the particular quality of spatial lyricism found in Rogers’s most recent maquettes.

Significantly, Rogers’s maquettes are never simply loosely-handled or ‘rough sketches’ (indeed, the Italian term for maquettes is bozzetti, literally ‘sketch’) but are finished works in their own right, in spite of being comparatively small in scale for this artist’s wider practice. What’s more, for the most part, Rogers’s maquettes closely resemble the final and enlarged sculptures which is not always the case with sculptors, given the various purposes for which a maquette or scale model is intended.

So, what of the significance and purpose of a maquette? Briefly, the longstanding artistic practice of making maquettes (French for scale model) ranges from the preparation of an indicative or small-scale ‘prototype’ that might be submitted, for example, to an architect or selection committee charged with the oversight of a public commission. Less formally and straightforwardly, the maquette serves as the means by which an artist explores, in the round, spontaneously and without restraint, the gist of an idea. The making of a maquette tests the formal options for a planned larger work and, especially where multiple maquettes are involved, resolves compositional challenges before proceeding to the more daunting, risky and expensive process of carving, modelling or constructing an ambitiously-scaled and often publicly-sited work.

Invariably, in Rogers’s case, while his maquettes clearly have a spontaneous quality of structure, they are always afforded a high degree of ‘finish’ with a strategically patinated surface much the same as will later be deployed for the final scaled-up work.

Over time, certain sculptors have been singled out for the particular interest or unusually expressive quality of their maquettes. An outstanding example is the Italian Baroque master Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), whose bozzetti were vigorously and spontaneously modelled in either wax or clay (which was subsequently fired to preserve the form) as preparation for the elaborate carved marble or cast bronze commissions for which Bernini is duly celebrated. As curatorial research for a 2012 exhibition of Bernini’s bozzetti at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art revealed, Bernini’s bozzetti do not always closely resemble the finished forms; a circumstance that usefully illustrates the exuberantly experimental nature of the working processes that underlie Bernini’s oeuvre.

What Bernini’s bozzetti do accurately anticipate is the sense of tumultuous movement and rich emotion that we associate with his major finished works, while the energetic play of light and shadow for which his sculpture is revered, is generated by a breadth and vigour of modelling, a process that for Bernini was swift and direct to the extent that the soft surfaces of his original wax or clay models bear the visible imprint of the sculptor’s thumb and fingers.

In the early modernist and subsequent decades, artists such as August Rodin, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Lyn Chadwick were known for their prolific and distinctive production of maquettes. Chadwick, for example, acclaimed for imposing and angular semi-figurative works executed in various metals, saw the production of maquettes as indispensable to his practice, making multiple small versions or variations of a composition before embarking on the expensive enterprise of executing the design on a large scale.

When, in the 1950s, Henry Moore’s practice shifted gradually from carving to modelling and casting,

his preparation for each major work ceased to rely as much on preliminary drawings. At the time, Moore himself stated that he preferred instead to resolve a composition ‘in the round’ by means of exploring ideas with multiple maquettes. These, nevertheless preserved the qualities of spontaneity and directness found in his drawings. A fastidious technician, Moore often made scale models of an intermediary size after completing a number of small maquettes. After making adjustments to account for issues of perspective and other considerations, it was these intermediary models that were used by Moore’s assistants to shape-up the full-size work which, in turn, would be consigned to a bronze foundry for casting.

Hepworth, likewise, made different versions of her maquettes, particularly for major public commissions and even, from time to time, had these maquettes produced in limited editions. Moore frequently did the same. Rogers’s maquettes, on the other hand, we note, are mostly unique casts.

Pioneers of modernism in Australia such as Inge King and Lenton Parr, both former members of Melbourne’s influential Centre Five Group, made copious maquettes in preparation for large welded-metal works or, in King’s later career, for cast bronzes. King made maquettes using thin sheets of wood while Parr devised his open, curvilinear compositions by simply bending and soldering highly flexible bands of steel. From these versions, Parr then assembled and welded heavier metal maquettes that were impressive small works in their own right, mostly painted black and only occasionally coloured. Copious small line drawings in sketchbooks sometimes preceded the making of maquettes in Parr’s case.

Given the geometric or formal purity of King’s sculpture, her maquettes are always accurate indicators of the final form and were intended for this purpose when handed over to expert fabricating contractors. So too, we recognize the close correlation between Rogers’s maquettes and the monumental final forms. A maquette for Folded (2003), for example, conveys the same sense of gravity acting (implausibly given the medium of bronze) on a section of massive, finely-ribbed but seemingly flexible ‘drapery’ as seen also in its large-scale counterpart. The same visual irony is present in the large and small bronzes of the same title. The larger version is in the collection of Pt Leo Estate Sculpture Park. The ‘draped’ form is as carefully articulated and patinated in the maquette as it is in the final work. But Folded belongs more appropriately to the earlier period of the artist’s practice that has been dealt with elsewhere. Whereas I wish to consider the increasing structural transparency of the subsequent work marked also, as it is, by experimentation with forms that evoke spiraling or similar rhythms – particular spatial dynamics that, to my mind, characterize Rogers’s most recent body of work.

Not that this kind of spatial dynamic is without precedent in the history of art or the history of sculpture. Far from it. The magnificent conjuring up of the fierce and irresistible forces of nature are there, most memorably, in the deluge and

tempest drawings of Leonardo, with their curling and crashing waves, billowing clouds and terrible vortexes of matter. Hokusai’s famous woodcut of The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1829–1833) says much in a single remarkable image about this same sense of a colossal turbulence of matter. And it is there too, notionally in slow motion, with the freeze-frame image of Rogers’s Rise (2011) and the preparatory maquettes (2010) for this major work. Brett Whiteley’s most dramatic wave paintings and drawings are further cases in point.

In terms of creative representation of natural forces but of a more benign kind, still loosely associated with notions of spiral- or vortex-like structure, there are the iconic early-20th century Jack-in-the-pulpit glass ‘vessels’ by American designer Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933). Often acknowledged as the quintessence of Art Nouveau, these organic glass forms (with their tantalizing iridescence not dissimilar to patinated bronze) rise up on narrow stems like mini waterspouts of unusual elegance and poise. Certainly, these Jack-in-the-pulpit vessel forms are works of abstraction but they do nonetheless allude to natural form (specifically the eponymous American woodland plant) and more generally to the wider rhythms of the natural world.

Compare these relatively small and fragile images (Tiffany created numerous variations on the theme) with, for instance, Rogers’s vastly larger, infinitely more robust and more elaborately articulated sculpture titled I Am (2012).

This is the towering and prominent commission installed in the public concourse at the National Airport in Canberra. Although more conspicuously tornado-like in scale and visual impact, together with its related maquettes, I Am can still be said to effectively evoke vegetal structure (albeit gigantic in kind) with its finely ribbed, unfurling form and its gleaming golden interior.

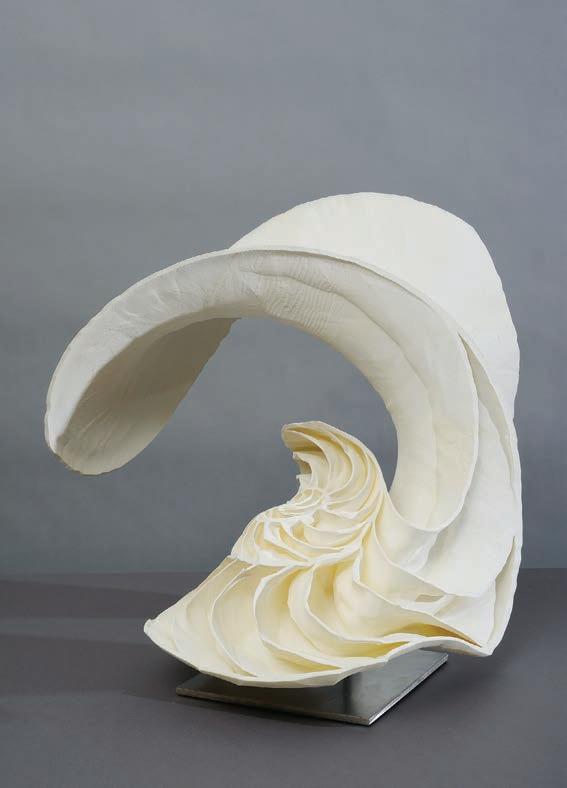

That said, the smoothly-contoured and flame-like maquettes designated as Tessera (2017–2019) are much closer to the understatement and simple profile of Tiffany’s creation than is the colossal I Am. Variously closed- or open-structured, and some incorporating tessellated patterns, the Tessera series again exemplifies the artist’s ongoing exploration of billowing, whirling or vortex-inspired forms suggestive of arrested motion.

This semblance of arrested motion extends impressively and diversely through the I Am and I Am Dancer series of works (2014–2016) but is there an attribute which is combined, on occasion and with restraint, with the whiff of a newly-emergent figuration. To wit, the thrusting profile of I Am (2016) is vaguely suggestive of the forward-surging torso of the most famous of Hellenistic marbles, the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre. Whereas selected works in the Come to the Edge (2015) series – entirely openstructured – are suggestive of flights of birds or even of individual birds, while Come to the Edge 3 (2015) and Embrace (2018) are plainly suggestive of dancing figures, such is the lyricism and spring of their compositional step.

This hovering of imagery between the stylistic poles of abstraction and figuration is a feature of the series just mentioned and recalls the equivalent and beguiling ambiguity cited by Tony Cragg in reference to his own tornado-like forms such as his remarkable Luke (2008) in the collection of the Pt Leo Estate Sculpture Park. From certain angles, Luke appears to be a spinning tower of elliptical forms, portions of which coalesce from certain vantage points, as a gigantic profile of a human head. Walk on around the sculpture, and this physiognomy dissolves back into an imposing edifice of billowing shapes.

Remaining in the realm of whirling or spinning illusion, we turn to the Resonance series (2017) of recent works with their volumetric generosity and streamlined profile. Here, we find no figurative allusion, rather we rejoice in the sheer exuberance of the billowing and seductively gestural forms, most of them balanced vertiginously on minimal bases.

These works, too, bring to mind the romantic reverie of Loie Fuller’s legendary ‘Serpentine Dance’. For our purposes, this comparison is achieved courtesy of You Tube by viewing the historic footage, shot in Paris in 1896 by film-makers Auguste and Louis Lumière, of another dancer clad in a long, loosely fitting silk gown with voluminous sleeves moving at random around a stage waving her arms above her head to create billowing wing- or cloud-like shapes accentuated by special lighting. There is something comparably seductive and engaging about the Resonance series of stainless steel casts.

l conclude by drawing a rather different parallel to those cited above and this is between the formally austere works Floating 1 (2018) and Kinetic 2 (2019) and the Constructivist abstractions of Russian modernist Naum Gabo (1890–1977).

Determined, in the interwar period, to distance himself from the conventional sculptural notions of mass and volume, texture, narrative and ornament, Gabo made a number of spatially dynamic abstractions (using intersecting sheets of clear plastic and nylon filament) that dealt exclusively with ‘the realities of depth and space’. By doing so he employed the then unorthodox process of ‘construction’, as opposed to conventional modelling or carving, just as he combined geometric abstraction with an animated deployment of materials to explore sculptural space. The twisting and spiraling sections of Gabo’s constructions underscore this parallel with Rogers’s later compositions.

As flagged briefly above, in the second decade of the current century, Andrew Rogers generates his own style of compositional vitality – an attribute we can interpret as a sculptural metaphor for the forces of nature, and of life itself. Above all else, these are life-affirming works of art, regardless of the small scale of the maquettes or the imposing size of the scaled-up versions.

A former Director of the Geelong Art Gallery and previously the Senior Curator of Sculpture at the National Gallery of Victoria, Geoffrey Edwards works now as a freelance curator and consultant to private, corporate and government bodies.

The author of various monographs, he has published widely in his fields of special interest including historical and contemporary sculpture, the decorative arts and Australian painting.

Currently, aside from his advisory work with Sydney’s popular Sculpture by the Sea exhibitions, his main role is curatorial adviser to the Melbourne-based Gandel family in respect of their remarkable new sculpture park at Pt Leo Estate on the Mornington Peninsula.

Growing 1996

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Spirit 1997

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Leading 1 1996

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Catching Wind 1997

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Macrocosm 1996

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Bronze and Silver 67 H x 35.5 W x 21.8 D cm

Rhythms of Life 1996

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia Bronze

Growth 1999

Geelong Gallery, Victoria, Australia Silicon

Evolution 1999

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Ripening 1999

Geelong Gallery, Victoria, Australia Silicon

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Molten Concept 12 2012

Polyamide 50.5 H x 24.5 W x 19 D cm

“The challenge is always to use materials in a new and different way, and make them convey meaning and portray form in a manner that has not previously been seen.”

Andrew Rogers

Andrew Rogers was born in Melbourne, Australia and attended Monash University, graduating with a Bachelor of Economics in 1968. He lectured as an Honorary Fellow part-time in the Department of Commerce at the University of Melbourne in the MBA course while pursuing a parallel, successful career in business and commerce.

Interested in art, during the 1960s he painted privately before turning to sculpture in 1989. His interest in sculpture was stimulated by the expressive power of the works of Auguste Rodin. However by 1995 this figurative focus turned to abstraction - exploring a dialogue between the rhythms of nature and patterns in mathematicsthe starting point of this retrospective exhibition.

Since the mid-1990s he has worked as a fulltime artist, in addition to his sculpture practice he has, since 1999, created monumental Land Art environmental installations under the title Rhythms of Life, the largest contemporary land art undertaking in the world, forming a chain of 51 massive stone structures, or Geoglyphs, spanning the globe. The project has involved over 7,500 people in 16 countries across seven continents.

www.andrewrogers.org for a full biography

2017 Expo Future Energy, Astana, Kazakhstan

Akureyri Museum, Akureyri, Iceland

Australian Consul General’s Residence, Kobe, Japan (2)

Balexert Cinemas, Switzerland

Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul, Turkey

Cirque du Soleil/Guy Laliberte, Canada, Tahiti and Spain (7)

City of Vienna, Nussdorferstrasse, Vienna, Austria

Curitiba, Brazil

Estate of Dr Simon Wiesenthal, Austria

Gibbs Farm, Kaipara, New Zealand

Golden Village, Marine Square South Multiplex, Singapore

Google Headquarters, California, USA

Grounds for Sculpture, New Jersey, USA (3)

Hall Arts, Texas, USA

Hall Park, Dallas, Texas, USA (16)

Hall Vineyard Inc., California, USA (8)

Harwood Center, Dallas, Texas, USA (2)

Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel (2)

Hokoku Construction, Kobe, Japan

International Conference Center, Jerusalem, Israel

Machu Picchu Municipality, Peru

Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California Davis, California, USA

Maroussi Multiplex, Athens, Greece

Nevada Museum of Art, Nevada, USA

Office of Hasfat Abiola, Founder, Kuridat Institute for Nigerian Democracy

Office of Vincente Fox, Former President of Mexico

Office of Jigme Lynpo, Minister for Culture, Bhutan

Residence of the Australian Consul General, New York, USA (2)

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel (3)

Ronald S Lauder Foundation, New York, USA

Tufts University Arts Center, Massachusetts, USA

Technion - Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel (Artist in Residence) (2)

Sapir, Arava, Israel

United Jewish Federation, New York, USA

Warner Brothers Complex, Taipei, Taiwan

Warner Village Cinemas, Berkshire, UK

Yale University, Connecticut, USA

2017 Expo Future Energy, Astana, Kazakhstan

Aspen, Colorado, USA

Bank Garanti, Istanbul, Turkey

Basel, Switzerland

Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul, Turkey

Cirque du Soleil/Guy Laliberte, Canada, Tahiti and Spain (7)

City of Jerusalem, Israel

City of Linzhou, Henan Province, China (2)

City of Vienna, Nussdorferstrasse, Austria

Curitiba, Brazil

Estate of Dr Simon Wiesenthal, Austria

Gibbs Farm, Kaipara, New Zealand

Grounds for Sculpture, New Jersey, USA

Hall Arts, Texas, USA

Hall Park, Texas, USA (16)

Hall Vineyard Inc., California, USA (8)

Harwood Center, Dallas, Texas, USA (2)

Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel

Kihei, Hawaii, USA

Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California Davis, California, USA

Office of the President of Israel, Israel

Proje4L Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art, Istanbul, Turkey

Sunset Beach, California, USA

State of the World Forum, San Francisco, USA

Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel (Artist in Residence) (2)

United Nations Environment Programme Ozone Secretariat

Young Presidents’ Organization, USA

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales

Australian National Airport, Canberra, ACT (2)

Bendigo Regional Art Gallery, Victoria

Bristol-Myers Squibb, Victoria

Castlemaine Art Gallery, Victoria

Citibank Building, 350 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria

City of Melbourne, Jolimont Terrace, East Melbourne, Victoria

City of Melbourne, King Street, Melbourne, Victoria

City Recital Hall, Sydney, New South Wales (2)

Copelen, South Yarra, Victoria

Crown Casino Complex, Melbourne, Victoria

Elgee Park, Red Hill, Victoria (2)

Geelong Gallery, Geelong, Victoria (3)

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Bulleen, Victoria

High Court Building, Melbourne, Victoria

Jam Factory, Prahran, Victoria

Jewish Museum of Victoria

Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW (2)

McClelland Gallery+Sculpture Park, Langwarrin, Victoria (5)

Melbourne Holocaust Museum, Elsternwick, Victoria

Mildura Art Centre, Mildura, Victoria

Montalto, Mornington Peninsula, Victoria (2)

Mornington Peninsula Art Gallery, Mornington, Victoria

Mount Scopus College, East Burwood, Victoria

National Alpine Museum of Australia, Mount Buller, Victoria (3)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT (21)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria (9)

Novotel International Hotel, Glen Waverley, Victoria (2)

Office of the former Prime Minister, The Hon. Kevin Rudd, Canberra, ACT

Office of the former Prime Minister, The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, Canberra, ACT

Office of the Prime Minister, Commonwealth Parliamentary Offices, Treasury Place, Melbourne, Victoria

Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Victoria

Point Leo Estate Sculpture Park, Merricks, Victoria (3)

Port Melbourne, Victoria

Residence of the Australian Consul, General,

New York, USA (2)

Sale Regional Art Gallery, Sale, Victoria

Shoreham, Victoria

Springvale Cemetery, Springvale, Victoria (4)

The Becton Corporation, Port Melbourne, Victoria

The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Parkville Victoria (8)

The Victorian State Government - City of Melbourne, Victoria

University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria

University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales

University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales (15)

Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne, Victoria

Wesley College, Prahran, Victoria

Westfield Corporate Ltd., Sydney, New South Wales

World Square Tower, Sydney, New South Wales (2)

Yabby Lake Vineyard, Mornington Peninsula, Victoria (6)

Australia/Israel Chamber of Commerce Awards - 1997, 1998, 2004 and 2007

Australian Israel Scientific Foundation

Australian National Airport, Canberra, ACT (2)

Caulfield, Victoria

F.C.A., Flinders, Victoria

Jewish Holocaust Museum, Elsternwick, Victoria

McClelland Sculpture Park Langwarrin, Victoria

Mosman, NSW

National Foods Headquarters, Docklands, Victoria (4)

One East, East Melbourne, Victoria (2) Point Leo Sculpture Park Merricks, Victoria

Presented to Former Prime Minister the Hon. John Howard, Commonwealth Parliamentary Offices, Treasury Place, Melbourne

Shoreham, Victoria

South Yarra, Victoria Springvale Cemetery, Victoria (4)

Temple Beth Israel, St Kilda, Victoria

Village Roadshow Theatres Presentation 1998, 1999, 2002 - Melbourne Cup, Australia

World Square, Sydney, NSW (2)

Ibiza, Spain 2014

TimeandSpacetheSpeedofLight 11m x 18m x 26.5m

Utah, USA 2013

Elements10.7mx3.4mx0.6m

Namib Desert, Namibia, 2012 SacredFire14mdiameter

Cappadocia, Turkey 2007 - 2011

TimeandSpaceGeoglyphPark 13structures,thetallestofwhichisa basaltarchthatweighs200tonsandrises toaheightof19.5m.

Presence24basaltcolumnsupto9mhigh

ADayonEarth31.5mx51mx9mand

19.5mhighArch

Listen 14.5mArchandAmphitheatre

Sentinels 8Basaltcolumns6mhigh

YesterdayTodayTomorrow 6mhigh

PredictingthePast4.2mx4.7mx1.1m

TimeandSpace24mx16mx5.3m

Siren 65mx100m

Sustenance100mx100m

Strength100mx50m

Grind100mx100m

RhythmsofLife100mx90m

TheGift60mx60m

Utah, USA 2010

Ratio13.5mx13mx2m

Dakshin Gangotri Glacier, Antarctica 2010 RhythmsofLife60mx60m

Chyulu Hills, Kenya 2010 Shield100mx70m LionsPaw40mx40m RhythmsofLife69mx69m

Yucca Valley, USA 2008

RhythmsofLife50mx50m

Atlatl,61m

Poprad, Slovakia 2008

RhythmsofLife35mx45m Sacred100mx100m

Jomsom, Nepal 2008

RhythmsofLife100mx100m Labyrinth60mx60m

Pokhara, Nepal 2008 GeoglyphKnot,60mx60m

Rajasthan, India 2007

RhythmsofLife90mx75m

Ratio8.5mx6.5m

Gobi Desert, China 2006

RhythmsofLife200mx200m

TheMessenger150mx150m

TheCaveman150mx150m

21 February 2014

In association with the 2006 Commonwealth Games You Yangs. Victoria, Australia Bunjil100mx80m

Eastern Park, Geelong, Victoria RhythmsofLife100mx90m

Akureyri, Iceland 2006 RhythmsofLife100mx100m Rune 100m x 100m Eagle100mx100m

January 2015

Kurunegala, Sri Lanka 2005 RhythmsofLife60mx60m Pride60mx60m Ascend6.5mx6.5m

Potosi, Bolivia, 2005 RhythmsofLife100mx100m

Presence 100m x 100m Circles100mx100m

Atacama Desert, Chile 2004 RhythmsofLife40mx30m TheAncients90mx88m AncientLanguage80mx2.8m

Arava Desert, Israel 2004 Ratio8mx32m

Arava Desert, Israel 2003 Slice80mx38.15m

Arava Desert, Israel 2001 RhythmsofLife29mx24m

Arava Desert, Israel 1999 ToLife38mx33m

1. Growing 1996 Bronze, 67.5 x 44 x 29 cm

2. Flora Exemplar 1996 Bronze, 64.8 x 31.4 x 21 cm

3. Observe 1996 Bronze, 62.2 x 37 x 26 cm

4. Entwine 1996

Bronze, 64.7 x 32.6 x 21.2 cm

5. Heritage 1996 Bronze, 65.3 x 29.6 x 23 cm

6. Spirit 1997 Bronze, 63.5 x 35.0 x 33.8 cm

7. Leading 1 1996 Bronze, 66.5 x 35 x 33.8 cm

8. Breaking Out 1997 Bronze, 110.4 x 57.4 x 35

9. Peak 1996 Bronze and Silver, 63 x 43.8 x 29.8 cm

10. Catching Wind 1997

Bronze, 78.3 x 42.5 x 22.6 cm

11. Macrocosm 1996

Bronze and Silver, 67 x 35.5 x 21.8 cm

12. Rhythms of the Metropolis 1996 Bronze, 67 x 26 x 22.6 cm

13. Harmony 1997 Bronze, 58.5 x 37.5 x 21.6 cm

14. Evolving 1996 Bronze, 70.4 x 42.4 x 31 cm

15. Balance 1997 Bronze, 57 x 79 x 36 cm

16. Rhythms of Life 1996 Bronze, 63 x 59.4 x 24 cm

17. Growth 1999

Silicon Bronze, 39.8 x 22.6 x 22 cm

18. Becoming 1999

Silicon Bronze, 41 x 23 x 20.5 cm

19. Living 1999

Silicon Bronze, 41 x 23 x 19 cm

20. Evolution 1999

Silicon Bronze, 38 x 48 x 27 cm

21. Organic 1999

Silicon Bronze, 38.4 x 21 x 16 cm

22. Balanced 1999

Silicon Bronze, 32.2 x 30.8 x 21.2 cm

23. Ripening 1999

Silicon Bronze, 39.4 x 27.6 x 25.4 cm

24. Mother Earth 3 2002

Bronze and Stone, 29.9 x 14.5 x 13.3 cm

25. Mother Earth 2 2002 Bronze and Stone, 22.5 x 15 x 7.4 cm

26. Mother Earth 1 2002

Bronze and Stone, 12 x 14.6 x 11.2 cm

27. Coiled 2011

Stainless Steel, 45 x 30 x 36.5 cm

28. Escalate 2001

Bronze, 32.6 x 19 x 16.4 cm

29. Flow 2000

Bronze, 38.8 x 61.7 x 19 cm

30. Rise 2000

Silicon Bronze, 44 x 38.8 x 24 cm

31. Rise 1 2010

Stainless Steel, 87 x 77 x 58 cm

32. Mount 2000

Bronze, 23.5 x 23 x 22.5 cm

33. Mount 2000

Bronze and ceramic, 47 x 45 x 44 cm

34. Ode to Kairos 2011 Stainless Steel, 30 x 28 x 28 cm

35. Folded 2003

Bronze, 106 x 74 x 50 cm

36. I Am 2012 Bronze, 65 x 29.8 x 24 cm

37. I Am VI 2016

Bronze, 137 x 118 x 88 cm

38. I Am 2014 Stainless Steel, 65 x 29.8 x 24 cm

39. Molten Concept 12 2012 Polyamide, 50.5 x 24.5 x 19 cm

40. Molten Concept 20 2012 Polyamide, 38.5 x 29.5 x 22.5 cm

41. Molten Concept 8 2012 Polyamide, 53 x 63 x 53 cm

42. Molten Concept 8 2012 Stainless Steel, 52 x 49 x 54 cm

43. I Am - Dancer 2015 Stainless Steel and Gold Polychrome 69 x 38 x 39 cm

44. Come to the Edge 1 2015

Stainless Steel, 73 x 61 x 49 cm

45. Come to the Edge 2 2015 Stainless Steel, 40 x 73 x 19 cm

46. Come to the Edge 3 2015 Stainless Steel, 69 x 66 x 63 cm

47. Tessera 0 2017 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

48. Tessera 1 2017 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

49. Tessera 1 Negative, 2018 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

50. Tessera 2 2017 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

51. Tessera 2 Negative 2019 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

52. Tessera 3 2017 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

53. Tessera 3 Negative 2019 Stainless Steel, 107 x 46 x 27 cm

Reproduced with the kind permission of McClelland Sculpture Park+Gallery

Andrew Rogers’s art is driven by an investigative pursuit of forms that can engender expressive emotion while resonating poetically with the underlying patterns and forces of nature. Underpinning this humanistic exploration of beauty and meaning is Rogers’s philosophical belief in the importance of life itself - the significance of nature, humanity and the role of the individual within the universe. (1)

His ambition is to embody in three-dimensional form what he refers to as the ‘rhythms of life’, whereby materials that are rigid and hard become seemingly tensile and malleable, and emanate both a dynamic corporal ‘presence’ and an internal spiritual ‘essence’. For him this transcendence defines aspects of the ‘human condition’, while the term the Rhythms of Life, is also the overarching title for a series of bronze sculptures produced from 1996-97 where a calligraphic zig-zagging ribbon twists and turns around a projecting arm supporting a sphere.

As a celebration of life, Rhythms of Life has become a leitmotif for Andrew Rogers’s work as a sculptor. In its free-flowing calligraphy it retains the immediacy of its conception as a charcoal drawing, while also incorporating Rogers’s deep love of music.(2) In this, it also relates to the concepts of Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), who often used musical terms to identify his non-objective paintings and who saw an analogy between music and art in terms of their effect on the observer and the attainment of a spiritual level or ‘inner resonance’. In Kandinsky’s book, Concerning the spiritual in art (1912), he referred to his compositions of geometric elements - circles, triangles and squares - as ‘vibrations in the soul’; and it is this kind of inner connection that Andrew Rogers seeks in his art. (3)

As a sculptor working with a variety of materials including bronze, stainless steel and polyamide, Andrew Rogers produces editions of individual works in both maquette and monumental scale. (4) These are limited in number with an edition of 12 being the maximum with 1-2 artist’s proofs, and in this respect Rogers maintains strict control by personally breaking and destroying the mold once the full edition has been achieved. This disciplined act metaphorically sums up the approach of Andrew Rogers as an artist who ‘breaks the mold’ with a self-directed and singular pathway that sits outside the usual career experience of most artists today. That is, in terms of sculptural training he is essentially an autodidact, whose desire to produce art came not from attending art school, but from intense study of sculptures in museums around the world.

Rogers’s initial love for art had been engendered by his family environment, and by art classes at secondary school taught by the eminent Australian painter John Brack, whose work and disciplined approach impressed him greatly. However, at University he studied commerce/economics, being attracted to the rigour of logic and mathematics, and although he toyed with the idea of undertaking a PhD in Philosophy, he was soon drawn into the world of business and finance, which necessitated constant international travel. When he started to make art privately he focused on painting; however the intimate experience of handling the casts and small sculptures by Rodin in the basement of the Musée Rodin in Paris was for him an epiphany that changed the direction of his life.

This museum holds most of Rodin’s sculptural oeuvre and Rogers was inspired by the supple modeling and expressive power of the artist’s bronzes with their strong emotional themes; as portrayed by

the individual figures in the ensemble The Burghers of Calais (18849), and in the monumental work, The Gates of Hell (1880-1917). He was impressed also by Rodin’s ability to fragment the body, as in The Walking Man (1907), a work that projects energy and vitality and is a powerful example of a sculpture that through non-specificity expresses the ‘essential’, and in so doing questions the nature of humanity. Rodin’s approach with its tactility and empathy struck an immediate chord with Rogers and encouraged him to try his hand at sculpture, which is quite literally what he did in 1989, by making a soapstone carving of his left hand, later casting it in bronze.

His decision to cast sculptural forms in bronze, necessitated working with a specialist foundry, and Rogers benefitted from the collaborative experience of working closely with a technical master such as Peter Morley at Meridian Sculpture in Melbourne who had worked previously with Henry Moore.(5) Rogers’s lack of casting knowledge presented an opportunity rather than a hindrance, for he took every opportunity to experiment and push boundaries in order to discover new directions and possibilities, a modus operandi he still adopts today working with new technologies and materials. His ‘apprenticeship’ was swift and over the next six years, he produced a number of sculptures of single thrusting/ reaching/imploring hands and groups of impassioned figures that with their gestural power reflected Rogers’s deep admiration for Renaissance bronzes and the work of Rodin in particular. In these figurative bronzes Rogers explored human endeavour through complex groupings of figures and individuals in various poses - gesturing with outstretched arms, reaching towards the sky and singular figures, entrapped, burdened or taking flight.

Rogers’s experimentation and his overarching desire to reach and express the uplifting spiritual core of the ‘essential’, set in motion an evolutionary shift. As a consequence he started to pare back the bronze surface in his figurative sculptures, cutting into the fabric, perforating the exterior surface, and opening it up to create see-through penetrations that he refers to as ‘ribs’. In this contradictory denial of the material properties of bronze, Rogers was seeking to achieve a spiritual dimension of weightlessness or ‘state of being’, that for him was a corollary to the ‘state of emotion’ produced by music. Initially he found expression for this in figurative sculpture that featured nude figures with musical instruments, especially the violin and cello, and even musical notes, which were exhibited in a solo exhibition at Meridian Gallery, Melbourne in 1993 titled ‘Mankind in the gesture of an individual’. Included were works that referenced Marc Chagall’s joyful, quasi-cubist painting The Fiddler, 1912-13 (Stedelijk Museum), with Rogers’s work of the same title being composed entirely of ribbed, cut-away bronze presenting an overall patterning of stripes that endowed the work with a sense of gaiety, levity and rhythmic movement.

Rogers was now on the cusp of a breakthrough where he would move from figuration to abstraction, in order to pursue the central goal of his on-going philosophical investigation into nature and humanity. With an inevitable evolution towards abstraction, his development of ribs and patterns in the bronze fabric of these early figurative works importantly provided a platform for further experimentation into weightlessness, movement and patterns. Rogers’s commitment to experimentation with materials and techniques had ineluctably set in motion an evolutionary shift as he gradually opened up the bronze surfaces of his works, eliminating the sense of mass and significantly endowing them with a new lightness. Increasingly, this approach would echo his perception of both the dynamism and fragility of life itself.

Central to this development was his admiration for the way in which the English sculptor Henry Moore cut away whole sections of his biomorphic shapes - thereby blurring the distinction between the internal and external, and making his human forms and groupings at one with the environment and nature itself. Moore, as Rodin before him, also provided evidence of the power of reducing forms to the essentials, of utilizing three dimensions and the importance of scale. In turn, Rogers now saw the potential for his sculptures to be located ‘in the landscape’, while also being ‘of the landscape’. In other words, nature itself was to assume a primary role.

This path towards abstraction and Rogers’s new focus on organic nature, was cogently made visible with the production of a new group of bronzes in 1996, beginning with the simplified leaf-like form of Growing 1996, where the smooth rounded bronze contours of this abstracted shape provided the impression of a large leaf gently unfurling with new life. This work, which represents the essence of germination, was first produced in maquette size and then in 2002 enlarged to monumental scale. (6)

A central characteristic of Rogers’s approach is to work in series, using the same elements within a concept to derive a number of different formats, and as a matter of course, producing each work in a range of sizes from maquette to medium scale, and when an opportunity occurs, in monumental scale for placement within the environment or public space. This was certainly the case with Flora Exemplar 1996, also from the first group of abstract bronzes, which in monumental scale soon took on an international public presence. The work represents a primary example of the trajectory in Rogers’s work towards natural growth with its plant-like forms and their sinuous almost Art Nouveau curves,

confidently revolving in three dimensions, while being symbolically referential to the human spirit. This form vaguely resembles a stem and bud, and, as Edmund Capon has noted, ‘its sheer expressiveness evokes in us emotions of human striving and introspection’. (7)

The organic imperative of growth and transformation continued in the next group of works including Entwine, Spirit, Leading, Heritage and Breaking Out, also from 1996, where a dominant coiled tendril springs upright from the base with the tensile energy of a shooting legume or a mechanical coiled spring. Despite being an enclosed spiral it nevertheless evokes associations with the spiral of the DNA double helix, and alludes to the notion of human technological advancement and new life breaking out of the armament of the past. This dichotomy and dualism between the natural and mechanical worlds seen in embryo here, has provided an on-going frisson in the direction and development of Rogers’s oeuvre, embodying as Igor Aronov has stated, ‘the interactions of life’s organic and technological forces apprehended in an intellectual, intuitive, emotional and spiritual manner to express the inner logic of life’s progressions’. (8)

Rogers’s interest in physics, mathematics, engineering and astronomy underpins the iconography and theoretical inspiration of the bronze and silver sculpture Macrocosm 1996, in which two curved forms with an ellipsoid or double ellipse effect are orbiting each other like moons to a planet, an effect that for Rogers ‘puts our human endeavor into scale’. (9) This summation of life and humanity’s relationship to the universe, reaches its zenith in Rhythms of Life 1996, a bronze composed of three basic elements: a curved line, described by Rogers as ‘the line of life’ (10) , that provides the support structure for life’s journey; a ball or sphere that could metaphorically be moving; and the swirling calligraphic

Leading 1 1996

tendril which is representative of the unforeseen, unexpected and uncontrollable occurrences in life.

This formalist combination of elements brings to mind Kandinsky’s theories, as expressed in Pointandlinetoplane, 1926, whereby the placement of key elements in a composition and their interaction produces certain expressive effects, which in abstraction communicates a spiritual cosmology that resonates with emotional power and meaning. (11)

The somewhat two-dimensional aspect of Rhythms of Life results from the calligraphic movement of the swirling ribbon that operates as a line in space, while the graphic power induced by the frontality of the composition elevates this work to a translatable codex for numerous other incantations in a variety of materials and monumental contexts. The two-dimensional aspect however, is unusual for Rogers whose sculptures are normally rounded for viewing in all directions, and in this respect the work calls to mind the innovative welded sculptures of American artist David Smith (1906-65), whose concept of ‘drawing in space’ saw him produce linear constructions that were expressive and gestural, and which posited a new language for sculpture. (12)

Rogers also admired the metal assemblage sculptures of Anthony Caro (1924-2013), who took on board Smith’s example, and constructed sculptures by welding and bolting together pieces of found metal, placing them directly on the floor or ground. Caro’s conceptual presentation of his sculptures, pedestal free in the environment, also echoed the break-through approach of Henry Moore who had integrated his work into the landscape. Moore, and then Smith and Caro, resolutely believed in the impact of the landscape in privileging the viewing and context of their work. Their innovation and experimental approach,

which had such great impact on the development of sculpture in the twentieth century, resonated with Rogers’s own recognition of the importance of continuous evolution and invention, which has continued to be a determining factor in the development of his sculptural practice.

By the end of the 1990s a number of developments were simultaneously opening up new directions for Andrew Rogers. The compelling humanist aspect underpinning his figurative work led to a commission in 1998 to design a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust as part of the Hadasa and Szymon Rosenbaum Holocaust Centre in Melbourne. This was an ambitious undertaking taking eighteen months to complete, with the final work, The Pillars of Witness 1999, comprising seventy-six bronze panels of literal imagery about the Holocaust combined with abstract elements that presented an overall symbolism of hope and affirmation for the future. This complex project, the first of many memorial works that he has produced, provided an opportunity for Rogers to collaborate with architects, engineers and the community in a process of consultation that he valued and for which his experience in business had equipped him well. (13)

In 1998 Rogers also undertook a six-week artist-in-residence opportunity at the Israel Institute of Technology at Haifa. Here, working with students, he produced an abstract bronze column Transform 1998, consisting of organic parts and an accumulation of machinelike elements, which in terms of its central coiling axis related back to the 1996 bronzes, Entwine, Spirit, Heritage, Leading, and Breaking Out. While in Haifa, Rogers visited the Arava Desert with the Chairman of the Central Arava Regional Council, who invited him to envisage a large sculpture for the site. This led to Rogers producing the first of his ambitious Land Art projects - the Geoglyphs, involving the construction

of massive stone structures in remote locations using traditional building processes. Commencing in 1999 in the Arava desert, where some four geoglyphs including a stone version of Rhythms of Life have been constructed, the Land Art works by Andrew Rogers now total some 51 structures in 16 countries across 7 continents.

The Geoglyphs gave Rogers a unique opportunity to work on an enormous scale, building stone structures that require complex engineering and tactical planning, along with ancient processes for moving stone in dry desert regions, on steep mountainsides, as well as in the deepest gorges and even on an Antarctic frozen lake. The experience of being in these extraordinary natural environments and the resulting body of work served to deepen Rogers’s engagement with nature and its force, with the knowledge that in time it will effectively bring on the detrition of these structures, consuming them back into the land itself.

On another level, his collaboration and engagement with various local communities, ensuring appropriate consultation and negotiating working conditions for workers above the normal rate for men and women equally, intensified his aspiration to make works that can embody universality, add meaning and bring hope, as Eleanor Heartney has commented, ‘Andrew Rogers’ Rhythms of Life can be seen as a response to its time, growing out of the search for meaning in an age dominated by globalism, renewed environmental threat, and the inescapable interdependence of the world’s peoples’. (14)

In terms of his studio work in Melbourne, 1999 saw a shift in Rogers’s methodology for the production of bronze sculptures. Normally this involved him first making a sketch, which was then translated into a twisted wooden armature and coated in sculpting clay that was carved and sanded to achieve a precise form. This was then cast into a highly finished bronze maquette, characterized by its uniform patina and finish. Now he shifted to utilizing thick sheets of sculptor’s modeling wax from which he cut individual shapes and organic forms that he progressively joined together, building them into three-dimensional ‘sketches’, which were translated into larger maquettes and then up-scaled to monumental public works.

This construction method of building up the various elements enabled Rogers to achieve the notion of organic growth and nature’s regeneration; visualized in Growth 1999, not as a flowing form emerging from the earth, but as an accretion of bountiful shapes and leaf-like forms built up along the upright stem.

Here too, the autumnal colours rising from green through red to brown produced by the use of ferric oxide and cupric (copper) nitrate, added to the sense of the work as an expression of nature’s fecundity with its patination echoing the germination and fruition of the botanical cycle. However, related works Organic and Balanced featuring this colourful patina, have a more distinctly industrial feel with long strips of bronze, slashed, folded over and skewered; while Ripening in its accumulation of bronze angled plates carefully balanced on four supports, verges away from nature towards a new form of organic constructivism, wherein Rogers begins to use pre-fabricated material sheets that retain the nature and traits of their industrial origin.

Growth 1999

Silicon Bronze

39.8 H x 22.6 W x 22 D cm

Geelong Gallery

With each series of works Andrew Rogers progresses the form and its defining characteristics through a number of different formats, in an exploratory and evolutionary progression while also pushing materials and scale to the limit; until all possible permutations that can deliver the qualities he seeks have been delivered. Characteristically, as the organic series was reaching its apex and with this spirit of innovation, he started to incorporate interventions of real rocks into the bronze sheeting as in the Mother Earth sculptures of 2002. As the title suggests there is a nurturing aspect to these works, however the stones are not simply nesting within the form, for some are straddled and restrained by bronze straps. And, in Mother Earth 1, the rock appears to break through the bronze sheets with the power and energy of an explosive force. Suddenly, it is as if we are witnessing a collision in space and the birth of a planet; and this sense of inter-planetary dynamic forces is equally evident in the singular work Coil 1999, where its thrusting, self-generated power and energy is absorbed back into its central core with the gravitational pull of a supermassive ‘black hole’ in space that increasingly pulls in matter to create a dense centre.

In the twisting configuration of Coil, crease marks are visible on the bronze surface at the points where the curve is accentuated, and these add to the impression that while the object is exerting enormous force, its extraordinary flexibility is an equally significant factor in its power and ultimate ‘presence’. Rogers’s fascination with transforming the base properties of bronze with its rigidity and unyielding toughness, into a form that can convey movement and animation, now presented a new exploratory direction for his work with a series of ‘ribbed forms’.

While he had introduced transparency by cutting slots into his early figurative works, he now experimented with adding ribs with a square profile onto flat sheets of rubber that were then cast in bronze. This endowed them with a repeating cog-like structure that in the circular movement of Mount 2000 is particularly reminiscent of modern industrialized engines. Here too, he continued with his determination to bestow malleability to bronze, transforming it into an animated twisting form, as in Rise 2000. (15)

The innovative spiral ribbed forms of the Rise series produced in the first year of the twenty-first century were revisited by Rogers in 2011 when, consistent with his determination to endow his works with a ‘lightness of being’, he employed stainless steel with its reflective surface adding to the sense of fluid movement. He also opened up the base fabric even further, with the dense mass of Coil becoming serrated and transparent, as in Coiled 2011; while the supporting fabric of Rise was dissolved in the later version, Rise 1; and Mount was spectacularly re-engineered as Ode to Kairos.

This period of experimentation was extremely significant for Rogers’s work going forward and led to a major development with his adoption of an industrially produced, ribbed rubber sheeting, which he could manipulate easily over an armature as if it were a piece of soft fabric, as in Folded 1 2006. This ribbed rubber sheeting echoed the forms that Rogers had been seeking in his seminal figurative sculpture

The Fiddler 1995 where he cut away the bronze to form linear patterns that projected a sense of movement. Now however, the concentration of his focus was on creating minimal sculptural forms with the appearance of being composed of soft fabric rather than rigid bronze; and here Rogers also explored the impact of gravity with the fabric taking on

a slumped attitude, as in Folded, and further, virtually collapsing with its strands pulling apart and drifting downwards in the ribboned form of Weightless 8 2007.

Just as the flat sheets of wax (approximately 10 millimetres thick), had served as the raw material from which Rogers cut the shapes and forms of his earlier organic series, for the Weightless series he now experimented with rubber sheets and wax, cutting a series of parallel lines across the centre, leaving the marginal edge for support. He then held the slashed sheet in a vertical orientation, allowing the wax ribbons formed by the cuts to fall into random gravity patterns. And here it is interesting to recall Robert Morris’s wall sculptures made of perforated industrial felt which also utilized gravity in the way they free-fell. However, while Andrew Rogers’s Weightless sculptures appear to be made of soft material they are instead cast in bronze and it is this contradiction, wherein what seems rigid now appears to be flexible, that intrigues Rogers.

In Weightless 8, Rogers has also made a further intervention in the freefall effect of gravity, with the pattern of cuts and the resulting ribbons being governed by his use of the Fibonacci number sequence (3, 5, 8, 13…)This sequence corresponds to growth patterns in nature and is intimately connected to the Aristotlean concept of the Golden Ratio or Mean. It has been utilized by Rogers in many of his Geoglyphs and Land Art installations, and is a governing principle in recent works where the graphic representation of the sequence forms an elegant spiral, as found in seed pods and sea shells. In the final work in the sequence of ribboned forms - Weightless 13, the bronze fabric with its series of cuts, folds in on itself, becoming like a cocoon or torso.

Rogers’s adoption of the industrially produced, commercial rubber ribbed sheets for the base component for his sculptures gave him a new medium with which to experiment, and in new body of work to translate into a major genre. His use of this ready-made material, has echoes in both the twentieth century Arte Povera aesthetic, and in the more recent Post-Punk utilization of common and kitsch materials, most notably taken up by Jeff Koons for figurative sculptures based on banal, commercially manufactured objects.

In terms of Rogers’s oeuvre his creative use of the industrially produced rubber material with its visual approximation to fabric, provided the springboard for the inspiring group of bronzes - I Am, Unfurling and Individuals, produced in 2012 and 2013, that are more concerned with transcendence than with the artifices of the material world. Here its capacity to be formed into dynamic, twisting cones of movement, enabled Rogers to endow his forms with a humanistic quality, so that each unfurling bronze is like a ‘personage’ with its own personality and spirit.

Initially for the I Am series the medium was bronze; then it was translated into polyamide, and in the latest manifestation, stainless steel has been used. In the bronze version the interior section is highly polished and reflective, creating a dramatic contrast with the patinated ribbed exterior. However, the stainless steel featured in the most recent works, exploits the inherently seductive properties of the highly polished bronze, and through its ultra-shiny, almost mirrored surfaces, creates visual ambiguities and enticing reflections of the external surrounding environment. (16)

This use of a mirror-like surface also echoes the creative aesthetic found in recent works by both Jeff Koons and Anish Kapoor. However, the articulation of the rippling envelope of the outer surface in Rogers’s works acts as a counterpoint to the private, highly polished interior of the organic form, and this poetic interplay reminds us that it is ‘the individual that makes our world a place of justice and compassion’. (17) Here, Rogers’s focus on the ‘human condition’ again comes to the fore as it had in 1993 with his first solo exhibition of figurative sculptures, where he was concerned to express a range of human emotions. Moreover, the 2012-13 works encapsulated the over-arching concern that Rogers has pursued throughout his sculptural practice, specifically his belief in life itself and the role of the individual within the community.

A further innovation in Rogers’s personal quest has been his adoption of available modern technologies - CAD (computer-aided design software) and 3D modeling that enable him to push the boundaries in terms of what was previously impossible in terms of fabrication and sculptural casting. This new capability has given life to his Molten Concept works of 2012, created in polyamide. This material is a macromolecule with repeating patterns that occur in natural proteins such as wool, but is also synthetically produced with plastic powder particles fused by laser for use in 3-D printing. This technology enabled Rogers to explore more fully his interest in patterns found in nature, such as the fractal patterns and symmetrical sequences that exist in plants, animals and even the non-organic materials of the earth; and also to work with the mathematics that help explain these features, such as the aforementioned Fibonacci sequence and the Golden Mean. The reference point for the Molten Concept group was a fossil of a nautilus shell observed by Rogers whilst working on one of his Geoglyphs in

a remote desert region. Specifically the focus of his interest here was the logarithmic, Fibonacci spiral contained within the inner case of the shell. This spiral allows the shell to expand incrementally and is a perfect example of the underlying geometry of nature that has inspired Rogers, not only for these Molten Concept works, but other works in his oeuvre. (18)

Needless to say however, nature provides only the starting point for Andrew Rogers as an artist whose humanist concern is to posit concepts, poetic encounters, collective memories, and imaginings for the future that embrace all aspects of the ‘rhythms of life’ that constitute our existence.

1. This essay reflects the author’s conversations with the artist, March 2015.

2. See Ken Scarlett, RhythmsofLife:theartofAndrewRogers, Macmillan, Australia, 2003, p.35.

3. Wassily Kandinsky, Concerningthespiritualinart, Dover Publications, New York, 1977, p.25.

4. Rogers has also worked in stone, crystalline marble from Italy and red granite from Brazil.

5. Meridian Sculpture was established in Melbourne in 1973 as Australia’s first commercial-scale lost wax foundry.

6. Growing 2002, large version, height 4.3 metres, Dallas, USA.

7. Edmund Capon, see Scarlett, ibid, p.49.

8. Scarlett, ibid, p.103.

9. See ‘Andrew Rogers in conversation with Robert Lindsay, 4 March 2015’, in AndrewRogers: ARetrospective:Maquettes1996-2015, McClelland Gallery+Sculpture Park, 2015.

10. Ibid.

11. Wassily Kandinsky, Pointandlinetoplane (1926), Dover Publications, New York, 1979, p.32.

12. See for example, David Smith, Hudson River 1951, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

13. Other memorials by Andrew Rogers include among others, the Buchenwald Memorial, Springvale, Victoria; and Rhythmsofthe Andes, Machupicchu, Peru.

14. Eleanor Heartney, AndrewRogers,Geoglyphs,RhythmsofLife, Edizioni Charta, Milano, Italy, 2009, p.10.

15. At this time Rogers was interested in exploring the possibilities of manipulating a flat plane into complex three-dimensional forms, an investigation that was enhanced by dialogue with the staff of the Department of Spatial Analysis at RMIT University, who are engaged on a major engineering project involving the construction principles underlying the completion of Antonio Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia Cathedral in Barcelona.

16. In his aim of achieving highly finished surfaces Rogers was inspired by the work of Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) whose minimal satin-smooth, polished surfaces provided the exemplar.

17. Frances Lindsay, AndrewRogers:Cometotheedge, Mossgreen Gallery, Melbourne, (exhibition catalogue), 2015.

18. Frances Lindsay, ibid.

Exhibition Dates: 10 April - 17 May 2019

Exhibition Curator:

Leanne Willis

Catalogue Design: Jacqui Klass

Photography:

Gavin Hansford, Andrew Rogers

Images:

Andrew Rogers

p2: © David Easton

p80: © Simon Peter Fox

p105: © Ben Symons

Text:

Leanne Willis

Geoffrey Edwards

Frances Lindsay

Andrew Rogers

Published by: Deakin University

©2019

The artist, the authors and publisher

Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any process, electronic or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Neither may any information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. All views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the publisher.

All works of art ©the artist

ISBN: 978-0-6483226-6-5

All rights reserved. This book is copyright.

Cover Image: I Am 2014 (detail)

www.andrewrogers.org for a full biography

Deakin University Art Gallery

Melbourne Burwood Campus

221 Burwood Highway, Burwood, VIC 3125

Phone: +61 3 9244 5344

deakin.edu.au/art-collection/

Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B