13 minute read

SLOT: A HISTORY

Tony Twigg

In 2002, Ray Hughes asked me to bring an exhibition of paintings to his gallery from my friend Charlie Co, a celebrated Filipino social realist painter. Along with Charlie’s show, I delivered an exhibition of Filipino abstract painting. I added a suite of my own constructions to paintings by my friend Gus Albor, and cardboard collages by Roberto Robles, whose work I had come to admire at Galleria Duemila where my own work is exhibited in Manila. With these shows completed I began imagining that I would need a gallery to go on exhibiting the art of my Filipino colleagues in Sydney. A vain fantasy! – until I realised that there was already a gallery, the front window of my studio, a shop at 38 Botany Road Alexandria. Gina Fairley, a fellow traveller with an insatiable curiosity about art, joined the project and SLOT was born. The ambition became, and remains, to engage with the art of the neighbourhood, the one around Redfern and the one around Southeast Asia. A wall was built, the ceiling fitted, a door contrived and lights installed. The first exhibition, a collection of my drawings, opened as I left for Manila to set up an installation at Pinto Gallery in October 2003. The second show was an installation by Catriona Stanton, an Australian artist and friend. As I was returning to Sydney from Manila my friend and artist Hermisanto handed me a tightly rolled wad of drawings, and they became SLOT’s third show.

Advertisement

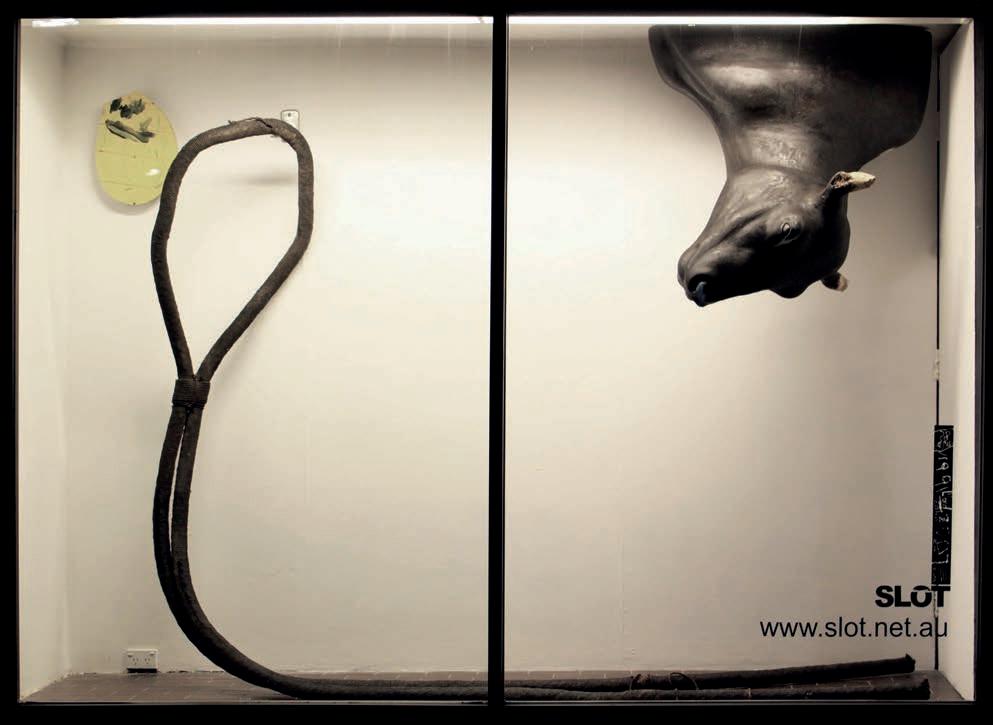

SLOT proposed that the distance between the Philippines and Australia could be negated with installations delivered as emailed instructions, to be realised by SLOT. Junyee, the grandfather of Filipino installation art is the only artist to act on the proposal and emailed one of SLOT’s most memorable early shows, Separate reality, as two jpegs and a few lines of text.

After moving to Alexandria in 2000, I watched with interest the interventions of a sign painter. He left hand-written signs offering the essentials of a transient lifestyle: a bed, a TV, a washing machine for sale, written on pieces of junk littered around the neighbourhood. Watching, photographing and collecting them revealed that they were far from littered – they were most observantly placed in the urban environment. In a couple of months, enough had been collected for a show, which was exhibited a few months later.

There was no response to a text sent to the sign painter saying his show had opened but one morning a pile of rubbish was mysteriously stacked in front of SLOT. It was art rubbish. And of course, it was delivered by the sign painter. There was a framed print of a Degas painting, faded to a lightdamaged blue, an empty frame already rusted, disastrous and discarded paintings on canvas, drawings, empty stretchers and much more, all stacked with great and possibly intuitive consideration. The splendid intervention remained in place and then, curiously, people began removing elements – presumably taking the rubbish home, to once again venerate it as art, unwittingly confirming the sign-maker as an artist with an alchemist power and SLOT as his agent.

Working in the studio behind SLOT, I noticed people pause to read the catalogue notes on each show posted on the glass door to the old shop. I guessed that they also paused to consider the works while they waited for their order from the take-away restaurant next door. In the street, I noticed people turn their heads, without breaking stride, to view the shows as they walked past. Late one winter night,

Sign painter of South Sydney

Homemade modernism 2004 [SLOT 10] with additional remarks by the artist walking home down Regent Street, a street of dark shuttered shops, I saw a single figure standing, gazing into the light of SLOT – I thought, warming the bones at the hearth of humanity. Once, someone slipped a note of thanks under the door; the butcher across the road became an art critic; and people mentioned gladly being caught in traffic at the lights on Botany Road because it gave them a chance to check out SLOT – the point being that SLOT was bringing art to people who would not normally think of going to an art gallery and doing it in a way that made art part of a life experience as opposed to a discrete cultural experience. Occasionally, the cognoscenti noticed. After an opening one night, I was sitting in a restaurant next to Tony Bond, then curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, who explained to me that he viewed SLOT from a car on his way to the airport, and as if to prove his point, went on to lucidly discuss the last six months of SLOT shows. After a while, people started asking how they might show at SLOT. The answer was, and remains, simple: send an email describing what you would like to do, attach some photographs of your work, there is no fee to exhibit – and sadly no fee paid to exhibitors, SLOT will get back to you with a date.

Over time, saying yes evolved from an inclination to an article of faith. In its history, SLOT has said no once, to a high school friend of my nephew. I can’t remember why but I regret it, because, while it is ridiculous to say that all art is equal, it is far from ridiculous to believe that all art has merit and so every art should have its turn.

Without question, the most luminous artist to show in SLOT is Roger Foley AKA Ellis D. Fogg, the creator of psychedelic light shows that illuminated the Counter Culture. This is the ideology that underpins the ethos of SLOT. Another reference is Tony Coeling’s Avago, a tiny window he maintained next door to Roslyn Oxley’s first gallery, the largest and coolest in 1980s Sydney. Tony Coleing offered the magnificent invitation to have a go and like his window, SLOT celebrates art made by everyone and art made for everyone.

But despite SLOT’s overt egalitarianism it is hard to find the shows that disappoint. Perhaps this has something to do with the space - it invites a single large work, as Tony Bond described “it’s the Roslyn Oxley of window galleries” where there are few physical limitations and no intellectual constraints.

Between these shows, others made works to accommodate SLOT’s proportions.

It was thrilling when Merilyn Fairskye asked to put up a show. Other artists followed: Ian Millis made two installations; Richard Tipping exhibited some photographs; Charlie Cooper put up a painting; Andrew Leslie tailored one of his optical works to fit SLOT; Christopher Hodges made an illuminated installation; Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan contributed three installations culled from their much larger museum works; Billy Gruner exhibited posters announcing exhibitions in another time and place; Joe Frost painted a mural of the other side of the street; and Ruark Lewis installed Banalities of a perfect home across the entire facade of the building. These are the landmark exhibitions. Generally speaking, these artists bent SLOT to accommodate existing works.

Loris Quantock, a school teacher who had developed a way of recording her bushwalks in meditative constructions made from twigs collected along the way, made one such piece that traversed SLOT side-to-side. Stephen Flanagan began by asking, “I’m not an artist but how can I show in SLOT?” and went on to produce a fascinating installation made from blueprints he had salvaged from an abandoned factory further down Botany Road. Russell Jeff knocked on the studio door asking if I would like to look at his paintings – of course, yes,

Stephen Flanagan

No fork 2 018 [SLOT 164]

Opposite Loris Quantock

33/59.4 south – 151/13.9 east 2009 [SLOT 62]

SLOT is interested in looking at all art. He was living on the “rock-n-roll” in the Waterloo Housing Commission towers and his story told of life as a discarded individual. His abstract paintings in contrast presented the image of an individual in command of a single vision at peace in its rendering. He produced a work for SLOT at the size of SLOT, glorious in its spiritual warmth and intellectual rigour – a clear triumph. Since then, we run into each other around the neighbourhood – he found a job working at a bakery in another suburb, still lives in Waterloo and seems a happy man. There would be few parables that illustrate as succinctly the virtue of social inclusivity over exclusivity.

Juni Salvador is one of the more enigmatic artists associated with SLOT. I had seen and admired his work in Manila but not met him until he arrived in Sydney with his children and his wife Edna who had come here to help set up a Montessori school on the upper north shore. Juni never found his way into the Sydney art world but in Manila he is part of a coterie of artists who were taught and influenced by Roberto Chabet, a celebrated and insightful Filipino conceptual

Russell Jeff Picture 2015 [SLOT 126]

Opposite

Juni Salvador

Fairy lights and fairy fails 2018 [SLOT 167] artist. Between trips back to Manila to make and exhibit his work, Juni contributed four revealing autobiographic works to SLOT that focussed on his Australian experience. As I watched these works evolve, I realised that he was devising a kind of installation that was idiosyncratically SLOT’s. Here a work occupies both wall space and floor space in a casual and spacious arrangement of elements. It’s clean with a theatrical presence that, like a diorama, is designed to be isolated in a vitrine. When Juni was returning to Manila, I commented on this by saying that I could see his and Chabet’s influence in other pieces being made for SLOT. He replied simply, “You noticed Tony”. It delights me to see in art a Filipino train of thought being shared locally through SLOT. It’s a grand claim but probably a true one that demonstrates SLOT’s successful interaction with its neighbourhood, around Redfern and in South East Asia.

Bellemore, Victoria Demafeliz, Gina Fairley, Leah Haynes, Pat Hoffie, Glenn Locklee, Mai Nguyen-Long, Ian Milliss, Constantine Nicholas, Sophie O’Brien, Emma Smith, Tracy Tucker and Chloé Wolifson. In 2015, Anie Nheu joined the project as collaborator. Since then, she has attracted many artists to SLOT, men and predominantly women who have produced individualistic and clearly resolved works while maintaining both a family and a job. Their lifestyle is a reflection of our contemporary society’s opportunities and expectations. The quality of their work however is a measure of their resolve that art should be made and shared. A resolve that SLOT shares, unreservedly.

Valentine Brown

(The new chum) c1980

Opposite

Valentine Brown, William Gaudinez

Romancing the colony 2017 [SLOT 153]

SLOT is not all my own work. Beyond the artists who are central to the project I have been assisted by friends and colleagues working as administrators, curators and web-masters, they are: Warren Andrews, Alex

Page 16

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan

Passage, another country 2017 [SLOT 154]

Page 17

Keiko Matsui

Scar vessels 2017 [SLOT 150]

A Series Of Opening Lines

Rebecca Gallo

Surveillance supplies – Something shuttered and empty-looking – A laundrette – Education agent (whatever that is) – A butcher – Takeaway joint – Variety store – Padded-wall kickboxing gym – Tobacconist

A brightly-lit window: thick-looking white paint, cracked in the corners from years of repainting, white on white. Dark brown floor tiles, a double powerpoint, large hinges stitching one corner together. A black vinyl logo on the window that’s been scratched into – lines and numbers, something rough, some unsolicited collaboration. Outside, the bricked footpath is littered with dry plane tree leaves that crunch underfoot. Traffic, always on this one-way street. Cars and trucks, and also (but with less density) pedestrians. It’s quiet at night.

Tony Twigg’s studio, at the intersection of Alexandria, Waterloo and Redfern, has a skin that faces the street, and for twenty years it has been dressed by other artists. Paint the walls, hang the work, talk to the artist, write about it, share it. Repetition and consistency. It’s how to get good at something, how to build skills, develop a practice. Doing it over and over again until it’s automatic, until it’s muscle memory, for twenty years, every month or so, a rhythm. Paint, hang, talk, write, share. It’s how you become an expert. It’s how you build something: a wall, a practice, a community. Consistency. Paint, hang, talk, write, share. It’s how passers-by get to know what art is, come to have feelings and opinions about it, an investment in it. Exposure, repetition, comparison: this work with last month’s work. What makes you feel something? What makes you angry, what do you walk past without really noticing, what work hits you in the guts before you know why?

SLOT is both a kind of offering and a protection, a closing in and an opening up. Tony’s space isn’t quite open to us, but a semipublic zone is created between studio and Joe Frost

Botany Rd Figures 2012 [SLOT 88] street. Run by Tony Twigg and Gina Fairley from 2003-2014, then Tony and curatorial collaborator Anie Nheu since 2015 as well as guest curators over the years, SLOT is social and collegial. It shifts the meaning of the studio, quietly refuting the myth of the sequestered lone artist. It’s neighbourly. It’s a series of opening lines, the start of a conversation offered over and over again to the street. an email, slip a note under a door or stop in for a chat. There has never been a ‘callout’ for proposals in the traditional sense but SLOT’s inbox (and door, metaphorically) has always been open. And they have only said no to a proposal once. Ask, and you shall receive an audience with Botany Road.

And this space is for anyone who wants to show there: for a while it was mostly friends and colleagues, people who were invited in. Then locals who enquired, artists who got wind, anyone with the confidence to send

SLOT operates differently to most artistrun spaces. These independent, grassroots groups of artists making space for other artists often echo, to varying extents, the structures of larger art institutions like commercial galleries, council- and state-run art spaces. Sometimes systems are deliberately borrowed, but often they are imprinted by proxy or

Vienna Parreno

War on Warhole 2009 [SLOT 60]

Opposite Pamela Leung

Sorry I no understand 2018 [SLOT 160] dictated by funding requirements. These can be at odds with artists’ own values. Artist-run spaces are complex and varied, generous and important. They do often end up gatekeeping in spite of themselves (curating a program to often opaque criteria), and they are a lot of work, so burnout is common. SLOT has, to a large extent, circumvented these pitfalls. It is completely independent: no funding applications or acquittals, no explanations or quantifying required. The system is deliberately simple. This is not to say that it’s not a lot of work – the maintenance of any space with an exhibition program takes time and energy. And access to long-term, stable real estate in Sydney is obviously very helpful here, and increasingly rare. But SLOT does not seek expansion, slickness or curatorial oversight. It seeks to start conversations between artists, their works and the street. mean heat and humidity control; on a cultural and aesthetic level, white walls and a sense of exclusivity, significance. Even for public galleries, audiences are self-selecting: not everyone chooses to visit these spaces, or feels like it’s for them, or has time and energy for it. The potential audience shrinks dramatically when it comes to commercial and artist-run spaces. People need to know these spaces exist, where they are and that they are open, before we even get to feeling comfortable entering them. Art also happens outside of these spaces: there is public sculpture, art in the lobbies and courtyards of major developments. Art that happens in home studios, in bedrooms, on people’s tablets or computers and is seen by few, if any. Art that is thrown up on the side of a building, or a train, or another piece of public infrastructure.

SLOT sits at the interface of public and private space, and locates itself between a range of modes for displaying and viewing art. As much as art seeks an audience, it also hides from it by requiring particular conditions for its display. On a practical level, this might

SLOT is related to all and yet is none of these things. It is on the street and visible 24/7. It’s not unsanctioned in the way that street art is, but it’s independent and democratic, and includes work by plenty of folks who wouldn’t call themselves artists. I doubt SLOT’s caretakers like all of the art that is shown

Poklong Anading

Untitled (gaze) 2007 [SLOT 42]

Opposite

Adam Laerkesen

My song is not your song 2018 [SLOT 161] there, and I think this is part of the point: they are facilitators, not arbiters of culture.

A SLOT caretaker writes about almost all of the exhibitions at SLOT. This writing demonstrates time spent with the work and (where possible) the artists, and reveals a depth of consideration: they place the work in broader contexts, and really seek to understand why each artist does what they do. These writings also reveal things about SLOT itself, like this from Tony’s piece about Julie Green’s 2021 exhibition:

“It might be a long bow to draw but in an art work there is a marriage between the artist and the viewer. Each arriving at roughly the same spot from different directions. For a moment caught in a single image before departing on divergent paths, each carrying perhaps, for a while at least some echo of their shared meditation.” a shopfront window that is forever offering, but never trying to sell you anything. Most of these encounters are small and unremarkable, and some cut through the traffic and noise and echo all the way down Botany Road.

This is what SLOT has been offering to the street, and to its surrounding community, for twenty years. A spot where encounters take place over and over again between artist, artwork and viewer; a moment of looking into

Rebecca Gallo is an artist, writer and producer who lives and works on Gadigal land and has been involved with artist-run spaces since 2014. They are a former director of Archive_ ARI which operated in Newtown, and a founding co-director of Pari, an artist-run space on Darug land in Parramatta.

Ruark Lewis

Banalities for the perfect house 2007 [SLOT 37]

Page 28

Jayanto Damanik Tan

Warung Peranakan Waginem 2019 [SLOT 171]

Page 29

Christopher Hodges

I’m dreaming 2018 [SLOT 169]

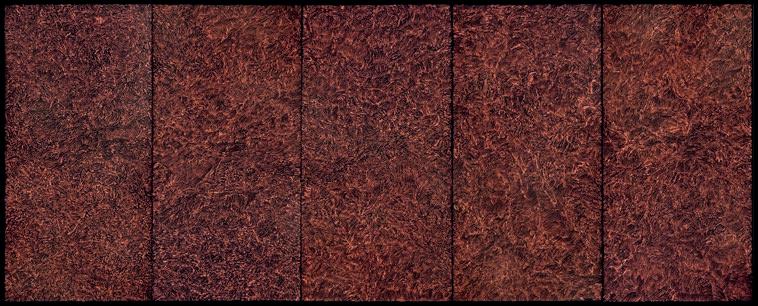

Roberto M.A. Robles

From the old pond I ponder (detail) 2007 [SLOT 34]

Opposite H.R. Ocampo, Gus Albor, Tony Twigg, Roberto M. A. Robles, MM Yu

Abstract art in the Philippines 2010 [SLOT 63]

Nglam Lzacy Tie from KL kartoon kids: art from KL 2006 [SLOT 33]

Opposite

Melbourne Aquino

Pinoy Cubism 2017 [SLOT 156]

Wong Perng Fey

Wo hui teng ni hui lai 2010 [SLOT 64]

Opposite

Tracy Luff

Passing through 2022 [SLOT 205]