33 minute read

London An apartment by Hollie Bowden with a tougher edge amid its softness

Feminine energy

A west London apartment with a tougher edge amid its softness

Words / Charlotte Abrahams Images / Genevieve Lutkin

Hollie Bowden is best known as a creator of edgy, rather masculine interiors, but as the west London apartment she has designed for her cousin, the model Lizzie Bowden, proves, she is equally adept at boho-pretty.

“The brief was very much to make quite a girlie apartment with the essence of Notting Hill,” says Bowden, and she has certainly delivered. This two-storey Victorian apartment on one of Notting Hill’s most prestigious roads is an eclectic treasure trove of a home, painted in shades of baby pink, peach and green. And the discoveries begin as soon as you step inside. The small entrance lobby is home to a pretty antique console and a richly detailed painting of two circus horses, a find Bowden loves so much she wishes she had kept it for herself.

Follow the grey-green floor into the living space and you find a pair of large linen-covered sofas, a tapestry-covered ottoman, a romantic Swedish armoire, and the most beautiful 18thcentury fireplace. “That was the first piece we bought,” she says. “It’s made from pink marble and helped to create a decorative language for the rest of the apartment.”

The living room opens into the dining area and it is here that the inspiration for the unusual green floor is revealed. Beyond the French windows lies a communal garden – a wildlooking, tree-filled space that was the reason Lizzie Bowden first fell in love with the apartment. “The original floor was mainly new and pretty awful,” Bowden says. “We talked about replacing it with stripped pine, but the views of the garden are so amazing as you walk through the house that we decided to paint it in Farrow and Ball’s Card Room Green, to lead you straight into it.”

The furniture in here speaks of gardens too. A set of the American designer Russell Woodard’s 1970s patio chairs sit around a vintage wooden table, and the pendant light is adorned with a delicate fern. But this is central London, not the English countryside, so there are edgier elements too – the Japanese stencils on the wall are arranged in a sharp geometric grid, and those woven Woodard chairs are made from spun fibreglass rather than the expected wicker. “I wanted to toughen things up a bit with some unpredictable pieces,” Bowden explains.

That unpredictability continues downstairs where the language of the apartment shifts slightly towards boudoir glamour. A luxe, leopard print Stark carpet leads into the main bedroom where, taking centre stage, there is a gloriously sumptuous bespoke bed upholstered in thick channels of green velvet. “Years ago, Lizzie and I stayed in a hotel in Monaco and it had this incredible bed with a curved headboard,” says Bowden. “I remember feeling really cocooned and cosy in it. This is a recreation of it, combined with some elements from a beautiful antique bed I came across.”

Previous page US designer Russell Woodard’s 1970s fibreglass patio chairs and a fern-draped light give the dining room an indooroutdoor feel

Facing page The entrance, with its antique console and painting of horses

Next page In the living room, the pink marble fireplace that Bowden sourced early on in the project helped to shape the apartment’s design language

Bowden’s boudoir touch is light and there are plenty of references to the antiques, natural materials and artisan objects found in the living space upstairs. Handmade Moroccan and old marble tiles line the walls and floor of the bathroom, the bed is draped in a heavy, embroidered suzani throw from Istanbul, and on the antique chest of drawers by its side stands an intriguing 1980s green-bronze face mask lamp designed by Garouste & Bonetti.

“It is a real challenge when you’re doing an eclectic project to create the right balance between eclecticism and harmony,” Bowden explains. “Anything goes – but everything also has to make sense.”

Bowden might be a self-described “collector, hoarder, magpie and beauty fundamentalist”, but she is also a deeply practical designer whose first consideration is always “how am I going to make this house function perfectly for the people who live here?”

This apartment is home not just to Lizzie Bowden but her young daughter, so the brief called for both a family home – with all the mess that brings – and a sophisticated, grownup space for entertaining friends. Creating this multifunctional home meant employing plenty of tricks of the trade, such as hiding the TV in that Swedish armoire and using the ottoman as a toy box. More importantly, though, it also meant going back to the bones of the place and sorting out the way the space flowed. “The apartment is on the ground and lower ground floor,” Bowden explains. “When I first saw it, there was a double staircase running from the living room down into the basement where the bedrooms are, which took up so much room that it ruined both spaces, so the first thing we did was to remove one side of it. It gave us extra room upstairs, but crucially, it also meant we could reconfigure the downstairs as well. Lizzie now has a bedroom with an ensuite bathroom and a door into the garden, and there’s a dressing room, a bathroom, a bedroom for her daughter and a laundry room down there, too.”

Upstairs, the idea was to create a familyfriendly, open-plan living/dining/kitchen space. The living room already opened into the dining room, but the kitchen was separate. Bowden was refused planning permission to remove the wall between the kitchen and dining room entirely, so instead she made a generous square arch. It’s a neat solution that delivers the same sense of openness, but also acts as a defining frame around both areas, giving each their own identity.

“This has been one of my favourite projects,” says Bowden. “I love how it looks – I’m doing up my own house at the moment, and it’s much more like this than the projects I’m best known for, but what I’m most proud of is how well it functions. We made a laundry room! That’s an amazing thing for a family to have.” There is indeed beauty in utility.

Facing page Clockwise from top left: a bronze lamp by Garouste & Bonetti; the new laundry room, created by removing one of two staircases; the apartment’s softness and informality, exemplified by a velvet-upholstered chair in the bedroom; Bowden is a great collector, and the artwork was sourced from far and wide

Next page The bespoke upholstered bed’s wrap-around design encourages a feeling of safety and sanctuary

ART & COLLECTING

A cultural review

by Hilma Af Klint. Read the full story on p92 The Swan, No. 16, Group IX/SUW Image by Moderna Museet, Stockholm. © Hilma Af Kint, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2021

Agenda

Sights to behold: a calendar of shows and fairs for the coming months

Words / Philomena Epps

Women in Abstraction, Guggenheim Bilbao

Until 27 February 2022

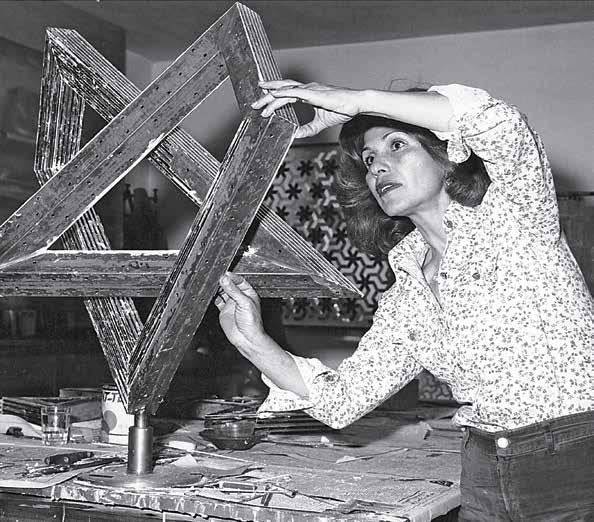

This survey exhibition reframes the history of abstraction through the work of over a hundred 20th-century female artists working across the visual and decorative arts, dance, photography and film. Attention is paid to the societal forces that led to the invisibility of the artists, in addition to those who resisted gendered labels or adopted a non-gendered identity, alongside those who laid claim to a particularly female form of creation. Pictured above is Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian in her Tehran studio; opposite is Barbara Kasten’s Metaphase 3 from 1986.

Estate of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian/ © Barbara Kasten Image courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery, New York. Thomas Dane Gallery, London; Kadel Willborn Gallery, Düsseldorf

Anni and Josef Albers: Art and Life, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris

Until 9 January 2022

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2021

Anni and Josef Albers met at the Bauhaus School and married in 1925, moving to the US as refugees in 1933. This show is dedicated to their artistic and romantic partnership and their mutual creativity, with over 350 works on show, from paintings to photographs, furniture, drawings and textiles. Anni combined traditional craft and weaving with the process of abstraction in modern art in works such as 1962’s Intersecting (above) while her husband pioneered colour theory through his now-iconic series of paintings, Homage to the Square (1950-76).

©2007 Philipp Scholz Rittermann. VG Bildkunst, 2021

LAS presents: Robert Irwin Light and Space, Kraftwerk Berlin

5 December 2021–30 January 2022

An East Berlin power station turned thriving cultural hub, the Kraftwerk building hosts this major site-specific installation by US artist Robert Irwin, a key figure in the West Coast’s Light and Space art movement. Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) is comprised of blue-coloured light tubes, typical of Irwin’s immersive environments, which challenge viewers’ perceptions by refocusing their eyes and their wider surroundings. Contemporary dance performances choreographed by Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar will take place during the show’s two-month run.

Martha Wilson in Halifax, Centre Pompidou, Paris

Until 31 January 2022

The Centre Pompidou is the first French institution to dedicate a solo exhibition to the work of US feminist and conceptual artist Martha Wilson. The 40 works included in its survey are focused on the period from 1972 to 1974 when Wilson taught at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Here she experimented with makeup and postures, creating a series of photographic works that explored subjectivity, female archetypes and gender transformation, such as Portfolio of Models (1974), where she role-plays as “Goddess, Housewife, Working Girl, Professional, Earth Mother, Lesbian.”

Alexander Calder, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Until 13 February 2022

Mies van der Rohe’s last solo project, the iconic Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, reopened in August following a restoration by David Chipperfield Architects. Alexander Calder’s monumental outdoor sculpture Têtes et Queue (1965) was installed when the gallery was inaugurated in 1968, and has been brought back in 2021, the starting point for a show of several more of the US artist’s mobiles and stabiles that viewers can experience in the museum’s infamous glass hall. The sculptures are also activated and set in motion once or twice a day, in order for viewers to fully appreciate their kinetic possibilities.

© Courtesy Martha Wilson, mfc-michèle didier and P.P.O.W. Gallery; © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe/ VG-Bildkunst Bonn, 2021

Photo: National Gallery/Hannu Aaltonen

The Modern Woman, Ateneum, Helsinki

11 February–27 March 2022

The 150 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints in The Modern Woman are all drawn from Helsinki’s Ateneum art museum, holder of Finland’s largest collection of art. Curated by the institution’s keeper of prints and drawings, Anu Utriainen, it explores 20th-century Finnish women from two angles – artist and muse – considering their changing role and position in the face of social, political and cultural changes. Artists include Helene Schjerfbeck, the recent subject of a retrospective at London’s Royal Academy, whose Californian (1919) is pictured.

Photo: Jack Hems. Courtesy the artist

Oscar Murillo, KM21, The Hague

9 December 2021–18 April 2022

Oscar Murillo (co-winner of the 2019 Turner Prize) has created a series of new large-scale paintings for his first solo exhibition in the Netherlands. Born in Colombia, Murillo is known for his wide ranging practice, spanning painting, work on paper, sculpture, installations and live events, and he is particularly concerned with globalisation and cultural exchange. His recent Surge paintings feature layers of oil-stick marks that form a thick impasto – a reference to the flow of water as a metaphor for an energy force that ignores the constraints of borders.

Courtesy Tracey Emin Studio. All rights reserved DACS 2021; Thomas Broadhead for OmVed Gardens; Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York; Photo: Pablo Leyva Hockney to Himid, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Until 24 April 2022

Celebrating 60 years of British printmaking, this show draws on Pallant House Gallery’s own collection of wood engravings, etchings, lithographs and screen prints. There are over a hundred works on show from 90 artists, from towering greats of British art such as Barbara Hepworth to storied mid-20th-century figures including Eduardo Paolozzi, and YBAs such as Tracey Emin (pictured).

Howardena Pindell, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

Until 2 May 2022

This is US artist, activist, writer and educator Howardena Pindell’s first solo institutional exhibition in the UK, bringing together work from her six-decade-long career. Pindell’s practice addresses issues concerning racism, violence, exploitation and feminism, often drawing on lived experiences or research; she is particularly engaged with the status and historical exclusion of Black artists. This winter, the restored 12th-century monastery turned museum is holding a solo exhibition dedicated to the Colombian modernist artist Feliza Bursztyn, a pioneer in kinetic sculpture who created immersive installations that utilised sound, light and movement. Over 50 sculptures, plus archival material and smaller works, will exemplify Bursztyn’s interdisciplinary and experimental approach.

Body Vessel Clay, Two Temple Place, London

29 January–24 April 2022

Subtitled Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art, this show has been guest curated by writer and academic Dr Jareh Das. The 80 works, including artists such as Bisila Noha (pictured), explore how the medium has been reimagined by Black female artists over the last 70 years, and how it has been used to express personal and political ideas concerning class, gender and postcolonial thought.

Feliza Bursztyn: Welding Madness, Muzeum Susch, Swiss Alps

18 December 2021–30 June 2022

Surrealism Beyond Borders, Tate Modern, London

24 February–29 August 2022

Arriving from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, this exhibition eschews surrealism’s Western European history in favour of an international approach. Showing nearly 80 years of work produced by those living in over 45 countries, the survey offers a renewed appraisal of how surrealism’s political interest in overthrowing the oppressive rules of modern society could be used as a tool and weapon in the struggle for freedom across the world. Artists from locations as far flung as Mexico City, Cairo and Tokyo include Argentina’s Ad Minoliti (pictured).

Photo: Shinjuku-I-Land Public Art Project / © 2021 Morgan Art Foundation Ltd./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Robert Indiana: Sculpture 1958-2018, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

22 March 2022–8 January 2023

Next year will see the first European museum exhibition of sculpture by US artist Robert Indiana. Its 47 works – 34 of which are sculptures, with six of those shown in the open air and the rest being painting and prints – will trace the development of his sculpture against the backdrop of six decades of social and political change. Responding to Indiana’s iconic LOVE sculptures and the themes of acceptance, peace and anti-discrimination, the venue will also present a Summer of Love – a season filled with events, interventions and artist commissions.

Reality check

A new way of seeing, or a speculative bubble? How the virtual world is shaking up the art market

When Martin Clausen and Kristian Snorre Andersen founded collectible design platform Adorno in 2017, virtual exhibitions weren’t really much of a thing. Cut to 2021, and that has completely changed. The regular schedules across the creative industries – fashion weeks, design festivals and art fairs – have been shaken up. This, obviously, has been partly through lack of option, with in-person events being a no-go during the pandemic, but it is also increasingly through disruptors who are presenting new ways of viewing and consuming the things we like to live among.

Digital exhibition spaces – and individual artworks – have been launched into the world en masse, sometimes in place of the physical experience, and sometimes alongside it. With the increase in demand for these kinds of virtual offerings, it seems as though the technology and imagination behind it has skyrocketed too, and what seemed revolutionary even at the beginning of 2020, now seems somewhat rudimentary.

For Adorno and Martin Clausen, it’s been imperative that they keep up. “We’ve always known that the best way of experiencing design and art is in real life,” he says. “But we set out to create the next best way, alongside our physical shows.” Since its beginnings, the company has invested heavily in staying at the forefront of technological developments. Of late, its budgets have swerved completely from the likes of PR and big exhibition spaces, and have instead been funnelled into 3D modelling and impressive production.

Its latest shows see collectors and visitors transported to an abandoned airport in Greece, before arriving on the rooftop of a Manhattan high-rise. At each location, they can roam around and view pieces placed into the environment, chosen by selected curators. “It’s not just about having an online blog with images, but having some kind of an immersive virtual space where people can really experience and engage with the design,” says Clausen.

Also taking advantage of these developing technologies is surface design specialist Giles Miller Studio, which launched its virtual gallery during this year’s London Design Festival in a bid to reach clients who may not be able to attend in person. The result, named V-Gallery, is set within a secluded wooded landscape and sees the studio’s work placed within a realistic gallery environment, complete with tour-guide-like voiceovers and a coffee bar where the studio’s new tile made from coffee waste is on show.

“Technology in this area has until now been lacking, but we felt the time was right for us to create a space which gives viewers a little more than the two-dimensional perspective our online presence has until now been able to offer,” says Miller, who adds that he felt it was important to steer clear of gimmicks. “If this format is harnessed to strengthen the presentation and conveyance of information, it will be hugely beneficial,” he says – referring to its place within a kit of parts, rather than a step towards a fully virtual future.

It’s a compelling argument, but of course there will always be purists. “The experience of appreciating physical works of art, whether it’s a sculpture, a drawing or an installation, can’t be replicated online, ever,” says Francesco Words Alice Morby

Facing page A virtual space for Dutch design, part of Adorno’s Designing Futures, a virtual event at the 2021 London Design Festival

Dama of Galleria Lorcan O’Neill in Rome. “Looking at a piece in person puts you right on the same spot its creator once stood. There’s tremendous power in that – it’s pure empathy.”

As such, Dama’s excitement about online viewing rooms and exhibitions has already died down. “During the pandemic, some galleries invested a hefty amount of money into them, and some thought the time of physical galleries was coming to an end. But within not even six months of that, we were desperate to visit a museum or a gallery in person and even the idea of scrolling over yet another online viewing room would make me queasy,” he says.

But beyond the actual experience of seeing the pieces themselves, it’s impossible not to look at the ways in which the rise of the online market has broadened the audience for collectible art and design. According to the Hiscox Online Art Trade Report, which published figures relating to collectors during the pandemic, 82 percent of new art collectors (defined as those who had been buying for less than three years) bought works online between March and September 2020.

Clausen says he sees this replicated through Adorno’s own network too: “Collectors are not only older, 60-plus-year-old people. In fact, over the past few years, we have seen our audience becoming younger.”

No examination of the impact of virtual reality on collecting would be complete without including a mention of NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, which have completely disrupted the art market. An NFT allows a digital artwork to be assigned a single owner, turning something otherwise easily reproducible into a one-of-a kind asset. In the same way that a physical work of art has a definitive owner, an NFT proves provenance and protects value.

Above Giles Miller Studio’s V-Gallery, showing its surface design products to a gobal audience

Facing page Norway’s virtual space at Adorno’s Designing Futures event, curated by Kirsten Visdal

“When NFTs first came out, the majority of galleries dealing in physical artworks had a pretty cautious approach to them, while some auction houses, which don’t entertain relationships with living artists, plunged into the digital market,” says Dama.

One auction house in particular, Christie’s, was the first of its kind to sell a purely digital artwork when it raked in a massive $69.3m for Everydays: The First 5000 Days by an artist known as Beeple. The collage of digital images, one created every day over 5,000 days, was not only the most expensive NFT to ever change hands, but was among the most expensive works ever sold by a living artist.

It’s clear to see the lucrative appeal, but Dama remains suspicious. “One listens to the news of all these NFTs sold for millions of dollars and the suspicion automatically arises that we’re in front of massive speculative operations. It certainly doesn’t make you think about democratisation,” he says.

Adorno has implemented NFTs into its own strategy, albeit in a slightly different way. Alongside each physical piece sold will be a certificate of authenticity in NFT format, rather than the traditional printed copy. As well as attracting a younger, newer audience, Clausen says that attaching the NFT to something physical may also make it an accessible concept for the more traditional collector. “It’s very important to connect the dots between the physical and virtual in order to get the real value,” he adds.

But for Dama, the connection to an artwork exists beyond owning it – be it virtual or physical. “[We need to] get rid of the concept of owning an artwork and start focusing on appreciating it instead,” he says. “There’s a beautiful sense of freedom in that.”

ARCHITECTURE

Surveying the built environment

Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Read the full story on p108 Image by Ossip van Duivenbode

Treasure chamber

Museum storage facilities are usually hidden from view, but a new publicly accessible depot designed by MVRDV is every bit as spectacular as the collection it holds

“The Depot is not a museum,” reads a panel of text affixed to the wall inside the Depot

Boijmans Van Beuningen, the latest addition to Rotterdam’s Museumpark. You could be forgiven for thinking otherwise as you move through this vast bowl-shaped structure. The building’s primary function is to provide storage for a 151,000-piece art collection, yet nothing about it says “warehouse”. For a start, it’s open to the public. Secondly, climbing its vertigo-inducing atrium is a bit like being inside a huge exhibition case. With glass walls and vitrines all around – so high you have to stretch your neck to see them all – everything feels like a spectacle. According to Winy Maas of MVRDV, the architect behind this radical project, the aim was to reinvent the concept of art storage. “It’s a prison of art, but a prison that you can open,” he says. “It’s more like a bazaar, where you can see all the stuff inside.”

The ideas behind the Depot first began to formulate back in 2004. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen boasts one of the largest and most prestigious collections of art in the Netherlands, yet for more than 20 years it had been using external depots to store works, as the cellars under the building were deemed unsafe. Not only were they too small but, with most of Rotterdam set below sea level, they were prone to regular flooding. For practical purposes, the museum felt there was a need to consolidate its multi-billion-pound collection to a single location that also included state-ofthe-art restoration facilities. Why build an anonymous warehouse out of town, when there was space on site to create something that could be a tourist attraction in its own right?

MVRDV has taken this idea and run with it, creating a building that is now billed as the world’s first publicly accessible art depot. Organised over seven levels, it contains five climate-controlled zones for different types of storage. There are 14 compartments for the museum’s own use plus an additional six that – in a smart commercial move – are leased to private collectors. There are restoration labs for a range of mediums, film booths and study rooms, plus gallery spaces for small exhibitions. Then, at the very top, a restaurant and events space open out to a rooftop garden planted with 100 birch and pine trees.

From the outside, the building makes a strong statement. Its distinctive curving form and mirror-clad facade were actually designed in a gesture to neighbouring museums – the idea being that the building has no rear facade and simply reflects its surroundings – but the effect is perhaps more impactful than expected, and the spaceship-style entrances certainly add to this impression. There may be some that take the Depot too much at face value, which would be a shame when there is so much more complexity going on inside.

The layout of the atrium, in particular, is multilayered. Staircases cross it in different places, offering views into glass-fronted storage areas where works are visible rather than boxed up. The glass vitrines, created by artist Marieke van Diemen, are carefully curated so that you walk over and under all kinds of artworks; van Diemen has envisaged it as a three-dimensional maze to explore. Meanwhile, lifts (for both artwork and people) whizz up and down as a backdrop. Maas says his dream was to create an environment where you might “walk between some Monets” on your way to the bathroom. Together, all these details help to demystify the archive environment and make it feel inviting. Words Amy Frearson

Images Ossip van Duivenbode

Facing page MVRDV’s Depot is a mirrored receptacle for art, topped by a rooftop garden

Above A fraction of the Boijmans Van Beuningen collection of 151,000 works of art, which is stored in 14 climate-controlled zones Facing page The atrium is criss-crossed with zig-zagging stairs, inspired by 18th-century architect Giovanni Piranesi’s fantastical prints

Facing page Artist Marieke van Diemen has created a series of vitrines in the atrium, to house a changing display of artworks from the collection Above Artist Olaf Mooij’s foam and leather car parked up in storage, alongside the spotted components for Yayoi Kasama’s Infinity Mirror Room

Growth industry

How Sweden’s Sara Cultural Centre is changing perceptions about timber as a structural building material

Words / Emma O’Kelly Images / Åke E:son Lindman and Patrick Degerman

Skellefteå in northern Sweden is going through a very modern evolution; known as Gold Town during the last century for its plentiful gold mines, this cold, remote city has, since then, been a place its inhabitants have wanted to escape from, not to. In 2023, however, Europe’s largest battery factory will bring new life to the unloved outpost, swelling its population from 70,000 to 90,000 people.

In anticipation of this influx, locals were asked what could make their city more appealing; their answer was a kulturhus, a cultural meeting point. Swedish firm White Arkitekter was asked what it would be made from; their answer was timber, sourced from local forests.

The result is the Sara Cultural Centre. Standing at 75m high it is the tallest all-timber tower in the country, and has already become a landmark attraction, brightening Skellefteå’s unassuming skyline. Inside, it houses the 20-storey Wood Hotel, six stages, the Västerbotten Regional Theatre, the Anna Nordlander Museum, the Skellefteå Art Gallery and the City Library.

It may be the region’s tallest timber structure, but it’s not its first. Skellefteå has a rich heritage and a tradition for building in wood that dates back to the 17th century; once the nearby wooden church town, Bonnstan, was the meeting place for locals. Now it’s Sara.

“We wanted to reintroduce timber to the city centre on an entirely new scale and refine the distinct wooden tradition of Skellefteå to meet today’s needs,” says White Arkitekter director Robert Schmitz. Everything, from the frames,

Above A 20-storey hotel rises up from the Sara Cultural Centre complex in Skellefteå, Sweden

Facing page A glass facade wraps the building, with the timber left exposed within

Previous page Open-plan spaces are made possible with the design of distinctive roof trusses combining timber and steel

lift-shafts, floors, walls and roofs are made in wood and pre-fabricated cross laminated timber (CLT). There are some concrete and steel elements – the open, grandiose foyer would not have been possible without them – and a glass facade that tackles the harsh north winds and temperatures that drop to minus 31°C. Sara’s blend of complexity and simplicity exudes what the late Finnish designer Alvar Aalto referred to as the “deeply human” feeling of wood. If it can stimulate more timber construction in Sweden and beyond, then the region’s abundant forests are a new ‘green gold’.

CLT is a 1990s invention that is finally moving mainstream; it is made from a sandwich of planks, glued together in perpendicular layers, creating a product so strong that it can used structurally. There are some persistent myths about timber – that it is not fire resistant, nor safe, nor durable – but Schmitz says that “we debunk these by proving the opposite. Projects like this are so important because they challenge public perceptions of what timber construction technology can achieve.” Next up for the practice is a 12m-high observation tower on southern Sweden’s Getterön nature reserve. Here, 140 wooden ‘ribs’ fold together to form an elegant hourglass silhouette. “With this project, we hope to show how timber architecture and engineering can create something fantastic that is sustainable both economically and ecologically,” says Schmitz.

Although timber towers are still unusual, perceptions are changing. This year in the US, wooden high-rises officially became part of the International Building Code. Portland firm

Above An education room; the building is home to a theatre company, museum, gallery and the city library

Lever Architecture was instrumental in the law change; for its 2016 project, Framework, the practice spent a $1.5m grant on timber building assemblies, testing fire, structural, seismic and acoustic elements. It met all the high-rise safety standards and, although the 12-storey tower was never built, was a catalyst project. “When you can show people images of a timber structure emerging intact from a twohour fire test, it makes an impact,” says Lever principal Thomas Robinson.

Robinson is inspired by the Pacific Northwest’s strong timber building tradition and pioneering US architects such as John Yeon and Pietro Belluschi, who developed a style fusing craft and modernism in the 1930s and 1940s. “There is a spirit of innovation and do-it-yourself independence in Oregon that is connected to the land,” he says. In 2019, Lever remodelled the state’s 1970s Nature Conservancy HQ in Portland with juniper and cedar cladding, sourced from the organisation’s conservation sites. And when it opens in downtown Los Angeles in 2022, the practice’s Spring Street project will be one of the city’s first major CLT office buildings. “Advanced wood construction is on the rise, especially on the West Coast,” says Robinson. “We’re seeing major tech companies, developers, colleges and universities embrace mass timber.”

The more we see of first-of-a-kind wooden structures that are built quickly, sustainably and inexpensively, the more perceptions will change. Scandinavia and the Pacific Northwest are already on board. The rest of the world just needs to catch up.

Above White Arkitekter's design celebrates the beauty of natural timber as well as its structural integrity

Invest in an annual subscription to Design Anthology UK to receive three issues a year, anywhere in the world

STYLE

Fashionable pursuits

Elettra jacket by Ulla Johnson. Read the full story on p127

Most wanted

Clothing, accessories and tech that are thoughtful, expressive, beautiful and good

Sirplus

Starting life in Spitalfields Market selling boxers made from offcuts from the shirt-making industry, Sirplus has grown to become a leading light when it comes to sustainable menswear. Increased demand means it can no longer make every garment from surplus materials, but it supplements this approach with environmentally friendly fabrics and native manufacturing where possible. New this season are a colour-block vest (opposite) made from British wool, and an orange corduroy workwear jacket/ overshirt (above), sourced from Italian overstock.

Ribbed lambswool vest, £125, corduroy overshirt, £195; sirplus.co.uk

Hyde Wares

Creative people can get pretty protective over their favourite pen, so Hyde Wares’ simple leather sleeve for that treasured possession is just the ticket. Its designer-maker is leatherworker Jonathan Hyde, who learned his craft living in Portugal. Now based in Sheffield, his raw materials are sourced from J&FJ Baker, the last remaining UK example of an oak-bark tannery, which uses a highly traditional process. Hyde’s products are made with longevity in mind and will only improve with age; he will stamp a name or initials on the pen sleeve at no extra cost, so there’s no doubting who that pen belongs to.

£30; hydewares.com

La Boite Concept

The coexistence of technology and craftsmanship is not new in the hi-fi industry, but no one does it with the added sheen of French elegance like La Boite Concept. Its new Square turntable features a minimalist design that is pleasingly off-centre; a veneered plywood top, available in oak or walnut, delivers stability and rigidity. If you need somewhere to put it, the brand has also just launched its Lines acoustic cabinet, a modular system in matching oak and walnut or matt black, with shelves that are backed with felt so that they fit snugly in the frame to prevent unwanted vibration.

€690; laboiteconcept.com

Aarke

There are endless ways to banish single-use plastic from your life, and a water carbonator (in lieu of endless disposable bottles of fizzy H20) is one of them. Swedish brand Aarke has rethought this normally utilitarian product as something a little slicker, with finishes including gold, white and matt black; its latest C3 model has had some subtle functional upgrades, including less plastic used in its manufacture. Founded in 2013 by friends and designers Carl Ljungh and Jonas Growth, Aarke is feeding a growing market for kitchen countertop gadgets for those who are discerning about design.

€199; aarke.com

Ulla Johnson

Perfect for pulling off a pattern-on-pattern layered look, Ulla Johnson’s patchwork Elettra jacket is made from a softly quilted cotton. The patches have been recycled from the brand’s past collections, so that nothing goes to waste. Need more of a coverup? Try the Sabreen coat, made from the same quilted material but in a longer style: both feature full-length sleeves, a boxy silhouette and a hidden zip. Brooklyn-based Johnson set up her label in 1998, and is known for her folky prints, romantic ruffles and dedication to natural materials, from alpaca wool to crisp cotton poplin and printed silk.

£565; ullajohnson.com

A potent protagonist

Curator Paola Antonelli, whose deceptively simple aim is to make design’s power known to all

Words / Alice Morby Image / Marton Perlaki

On 30 April 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic, Paola Antonelli and design critic Alice Rawsthorn created the Instagram handle @design.emergency. At a time of extreme uncertainty, the pair wanted to use the page to “explore design’s role in building a better future”. Each week, they would invite pioneering individuals to tell their story, contributing to a wider conversation about the importance of design practice as a whole. Interviews have included medical illustrator Alissa Eckert, who helped to visualise the Covid-19 “spiky blob”, and more recently, Swiss artist Ursula Biemann, whose work aims to tackle the world’s ecological predicaments.

Presenting projects that tackle the complex social, political, economic and ecological challenges faced by our contemporary world is what Antonelli does best; above all, though, her goal has been to make design known to the world. Trained as an architect in Milan, she joined MoMA in the mid-1990s and now holds the role of senior curator of the institution’s architecture and design department. Her exhibitions have covered everything from sustainable materials, design and its relationship to violence, and the meaning of fashion and clothing. She’s even acquired video games for the museum, including Pac-Man and Tetris – which wasn’t without snark or remark from critics. Not that it bothered Antonelli; it’s all part of raising awareness of the design of everyday life.

Examining the role of the curator through Antonelli’s work feels in equal parts thrilling and settling. At the centre of an industry driven by commodity and luxury, she cashes in on design currency in places others perhaps didn’t know existed. She remains committed to making sure those who leave her shows, or watch her interviews, or simply scroll through her Twitter feed, feel they understand their own relationship with design.

© Copyright 2021 Design Anthology UK

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, scanning or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except where noted.

Views expressed by authors are not necessarily those of the publisher.

FSC™ certification ensures that products come from well-managed forests that provide environmental, social and economic benefits.