August 2024

As with any project, success in developing a design code depends on adequate resourcing. Having the right budget and time are important factors, but so too are having the capacity and the right knowledge and skills. It therefore should be one of your first considerations when developing a code.

If you already face pressures on funding and staffing, you are likely to be concerned about how you can produce a design code on top of your existing duties. Fortunately, experiences from the Design Code Pathfinder Programme show that some of these resourcing needs can be overcome with good project planning and by finding practical ways to make the most of your existing resources. The following piece summarises some of the key lessons learned from Pathfinder experiences in relation to making efficiencies in producing codes.

At the start of the coding process, consider in detail what you need to do to prepare, test, adopt, implement, and monitor your design code. Also anticipate how much of the work can be carried out in-house and how much will have to be outsourced to external consultants. This will help inform the length of the project, who the major stakeholders are, what knowledge and skills you need and how much staff time the work will absorb.

Every case is different but results from a 2024 survey1 of Pathfinders showed that it took between one and two years to produce a design code, averaging out at 19 months. The survey also showed that, while many of the stages in the process took roughly the same amount of time, detailed coding took proportionately longer – over a quarter of the entire project duration.

Results from a 2024 survey of Pathfinders showed that it took between one and two years to produce a design code, averaging out at 19 months.

1 The Design Council’s 2024 Pathfinder Programme Survey secured responses from 10 Pathfinder teams about the resources and skills required to produce a design code.

27%

What percentage of your time was spent on each of the various parts of your project?

A 2024 survey of ten Pathfinder teams found that nearly a quarter of the project duration was taken up in detailed coding work.

Source: Design Council

A detailed resourcing plan will help to calculate the rough costs of developing and implementing your design code. Securing adequate financial resources for the entire exercise was a common concern for many Pathfinders and while this is a key part of the resourcing plan, financial costs might be offset by drawing on internal skills and staff resources, agreeing crossfunding from multiple directorates within

the local authority, or possibly sharing resource and expertise with neighbouring authorities. Similarly, it might be possible to secure financial or in-kind support from stakeholders, statutory consultees, and landowners of strategic sites.

For more on these topics, see ‘Managing code creation’ and ‘Bridging siloed working’.

Having the right structure, skills and mix of experience on the team responsible for developing your design code will help you to manage resources for successful delivery and adoption. Similarly, this team must have agreed an efficient way of working for effective partnership. Your initial resourcing plan will have identified what work you can do in-house – including with colleagues from other directorates – and what work is better procured externally. While planning teams have plenty of relevant skills and contextual knowledge, you may need to consult colleagues from other departments or procure people with skills in, for example, urban design, heritage, landscape or highways.

Procuring consultants is not always quick or straightforward. The survey of Pathfinders found that the process took on average 2.3 months, regardless of whether the Pathfinder had existing relationships or service agreements in place.

It makes sense, therefore, to have analysed your capacity to carry out the work inhouse at the outset, and to only procure external consultants if doing so is justified on grounds of cost-effectiveness, time and quality.

Trafford’s development management team determined that it made sense for them to lead on preparing the content of their design code. They were responsible for public consultation, testing and deployment too. While they used their framework consultants selectively to help develop the digital platform, graphic content, website hosting and maintenance, the core work and underlying evidence and analysis was all conducted in-house.

Initially the East Riding of Yorkshire Council Pathfinder team intended to develop their code in-house in order to “build skills internally”. Time constraints led to them appointing a consultancy to work with. The briefing and process of reviewing documents took longer than anticipated, making the project less efficient than the Pathfinder team hoped. They concluded that in future they would be likely to use consultancies for smaller sections of work, such as consultation or graphics, rather than to work alongside them on the main project.

Introducing Design Codes – a video showcasing the work undertaken by Pathfinders as part of the Design Code Pathfinder Programme, 2023.

Video: Design Council.

Medway Council developed their design code with a multi-disciplinary team led by BPTW, with whom they had an established relationship.

BPTW and the wider consultant team brought varied expertise to the table, including urban design, community engagement, landscape and public realm design, transport and highways.

This collaboration helped fill gaps in the Medway team’s skillset, provided focused production capabilities with an emphasis on specific disciplines when needed, and offered the vital ability to synthesise ideas, resulting in a richer and more “operationalised” design code. BPTW’s approach was enthusiastic and collaborative, two virtues identified by the Medway team as important ingredients in the overall success of their project. To find out more, watch ‘Introducing Design Coding’.

Even when a budget is agreed and the funding secured, there is still the risk that costs will creep up in unanticipated ways as your project unfolds. To counter this risk, you must manage your plan vigilantly and make the most of the resources at your disposal.

Most Pathfinders highlighted that, as well as having a clear vision, it was important to have a defined scope of work right from the start, something that is emphasised in ‘Design Coding in Practice’. Many of the Pathfinders were surprised at how long this process took, so make sure that you afford it plenty of time.

A key ingredient in refining the scope is to first consult with your development management team. Thereafter, you must clearly explain the scope of work to other stakeholders as you start to engage with them. This will help them to focus only on what is necessary, encouraging more efficient and effective use of available resources.

A narrowly scoped code will make implementation easier because the project team can concentrate their time on the most important tasks, policy areas and key design components and make better use of resources. It will also support adoption of the code at a later stage, as described in ‘Laying the groundwork’.

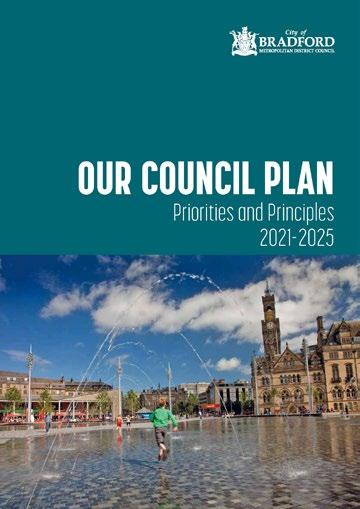

For example, the City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Pathfinder team found that defining their scope of work clearly and early helped to limit subsequent changes, which run the risk of delay and increased costs.

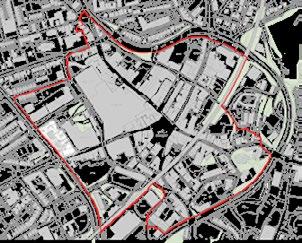

To emphasise their focus on new, high quality, viable and affordable urban housing, the Bradford team’s draft design code has been developed “primarily to support the policy for Urban Housing (HO3) within the Local Plan, which promotes intensifying housing density within appropriate ‘urban’ areas”.

Knowing what you want to do is half the battle. The other half is knowing how you can do it. In other words, you need a wellstructured and deliverable project plan. It must set out the main stages for developing the design code and identify risks and dependencies, which should be done in collaboration with other stakeholders.

For example, the Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team consulted their development management colleagues not just in defining their scope of work (which focused clearly on four development types) but also to set a robust project plan. It included testing phases that used a set of planning application case studies to be assessed using drafts of the design code. This allowed the Lake District team to assess the usefulness of their design code in advance of adoption, saving them from undesirable delays, additional work and unanticipated cost.

While the costs incurred in preparing a code can be a concern for local authorities, the Pathfinder programme has highlighted that significant returns can be achieved from the coding process.

Once adopted, codes can provide wider benefits by promoting inward investment, delivering on corporate objectives and driving development and regeneration. This is because a design code has the potential

to make the planning process more efficient by speeding up assessments, improving applications, minimising appeals, and helping junior development management colleagues to develop their competence sooner. A design code can also attract inward investment by driving development and regeneration, which in turn will help the local authority to deliver its wider corporate objectives for social and environmental good.

In developing their code, the City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Pathfinder team had two important objectives closely aligned to the council’s strategic plan. First, they wanted to improve clarity on expectations for new development through their planning approvals process, thereby saving time. Second, they wanted to deliver a greener and more sustainable street network and increase the level of street adoptions through Section 38 highway agreements.

Elsewhere, the Town Centre Design Code developed by Mansfield District Council supports their corporate vision, which sets out high-level objectives for placemaking in the town. Overtly expressing how the intended code would align to their corporate vision in reports to various committees, such as the scrutiny commission, cabinet, and mayoral report, was a successful tactic. The code was received positively at later stages of the process, aiding its adoption.

We will grow our local economy in an inclusive and sustainable way by increasing productivit y and suppor ting businesses to innovate, invest and create great jobs.

D e c e n t Ho m e s

We want ever yone to have a comfor table home which meets their needs and helps

them lead fulfilling lives.

G o o d S t a r t , G r e a t S c ho o l s

We will help our children to have the best star t in life by improving life chances, educational at tainment and overall qualit y of life for all young people regardless of their background

We will help people from all backgrounds to lead long, happy and productive lives by improving their health and socioeconomic wellbeing

S a f e , S t r o n g an d A c t i v e C omm u n it ie s

We want the Bradford District to be a place where ever yone can play a positive role in their communit y and be proud to call the district their home

We will make it easier for individuals, households and businesses to adapt, change and innovate to help to address the climate emergency, reduce carbon and use resources sustainably

We will be a council that is a great place

to work and reflects the communities we

ser ve Our people will have the tools to do their jobs ef fectively We will manage our resources well and seize all oppor tunities to bring funding into the district We will provide good, accessible ser vices.

Bradford council’s priorities as outlined in their strategic plan.

Chatham Centre Design Code 2050 vision.

The Medway Council Pathfinder team focused on the centre of Chatham, which has underperformed for many years. Developing a vision for change – for a more vibrant, greener and commercially successful urban centre – was therefore the focus of their code, including significantly growing the centre’s residential population to support the high street. The code is now at the heart of their marketing strategy, helping to improve Chatham’s branding and identity. With the potential to unlock a number of redundant sites, the code’s long-term benefits and return on investment have the potential to substantially offset the cost of its initial preparation. Medway feel confident that return on investment will be considerably more than the initial expenditure.

As part of this effort, the Council is also exploring innovative funding and delivery models to demonstrate how Medway’s development company can lead by example. This work aims to assess whether long-term patient investment can be leveraged to develop masterplanning areas identified within the code, particularly where Medway have significant land holdings. This work is exploring ways to promote local ownership through a ‘Medway Mortgage’ based on pioneering rent-to-buy initiatives that are yet to be fully embraced in the UK but have been used effectively abroad. These delivery approaches show how local authorities can use design codes creatively to address financial challenges while focusing on long-term quality delivery.

Using national, regional and local guidance and learning from relevant third-party sources will help make efficiencies in resourcing. Guidance will always have to be tailored to your unique needs and circumstances, but even so, using it will speed up your project and help you to avoid problems.

The National Model Design Code (NMDC) is an important point of reference with Part 1 setting out the process of preparing a code, while Part 2 contains detailed guidance notes on the generic contents of a code.

The Medway Council Pathfinder team drew directly on the NMDC. Using its structure helped them to be clear about the process and content of their code and therefore to manage resources efficiently. In particular, they understood that the success of the code required strong graphic communication, including diagrams, illustrations and a clear document structure, which can be very labour-intensive to produce. Their team was able to circumvent some of that difficulty by re-using imagery from the NMDC, which is permissible within the NMDC copyright status, and used the same drawing style for bespoke Chatham illustrations to blend the two.

This piece was written in collaboration with Peter Neal, an independent consultant and expert in planning, design, funding and management of green infrastructure frameworks, urban parks and the public realm.

Peter Neal – Design Council

Although much of the work involved in developing a design code will be led by planning teams, lessons learned from the Pathfinder programme confirm that it is important to collaborate with many other local authority departments from the outset. This allows you to acknowledge and account for differing priorities, needs and concerns, which improves both the code-writing process and its outcomes, helping the code to benefit as many parties as possible.

Results from a 2024 survey of the Pathfinders2 confirmed that the code-writing process was usually led by the planning team. They are best placed to leverage the necessary political support and make sure that the code is in line with local plans, policies and objectives. The survey results also stressed the vital role of collaboration.

Tactics for effective collaboration included conducting focused workshops at key stages to ensure that various service delivery teams and interest groups across the council – including elected members and development management colleagues – are involved. Previous research findings3 also

showed that it is helpful to nominate ‘coding champions’ from these groups.

Here are some of the other key lessons learnt.

Collaboration across departments and directorates allows you to align your code with the local authority’s wider corporate priorities. These are likely to include growth and regeneration, strategic development, placemaking, affordable housing, climate resilience, community health and wellbeing, and equality, diversity and social inclusion.

Striking the right balance between meeting the code’s core planning objectives and taking opportunities to progress relevant corporate priorities is a strategic judgement that can only be made with adequate engagement across all parts of the local authority. Doing so will help you not only to work out and agree a clear, achievable and relevant scope for the code but also, importantly, to secure leadership support.

2 The Design Council’s 2024 Pathfinder Programme Survey secured responses from 10 Pathfinder teams about the resources and skills required to produce a design code.

3 Design Council (2023) Design Code Pathfinders Programme: Supporting local authorities and neighbourhood planning groups developing design codes. Available at: Design Codes – Design Council

The City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council’s design code’s focus is on housing as a way to improve quality of life and address deprivation. This is directly related to the Council’s Corporate Plan, which has a priority to: “meet the needs and aspirations of our diverse and growing population” with “more high quality homes in neighbourhoods where people want to live and can thrive” and to “help ensure the district has green, safe, inclusive, and cohesive places which people are proud to call home.”

Feedback from community and stakeholder engagement revealed specific ways in which the design code could respond to these aspirations, materially affecting the detail of the code’s development. Equally important to the project was the willingness of internal colleagues to engage right from the start, described by the Bradford team as one of their “strong points”.

Reflecting on the coding process, the Bradford team highlighted the importance of establishing support from corporate leadership to help deal with pressures as they arose over the course of the project.

Step 1: Town Wide Design Rules

Read and apply all TOWN WIDE DESIGN RULES.

Go to Part B: Spatial Elements

Chapter 5: Town Wide Rules (from page 36).

Step 2: Area Specific Design Rules

Read and apply applicable AREA SPECIFIC DESIGN RULES.

Chapter 6: Area Specific Design Rules to identify area location within the town centre (Area 1, 2 or 3) (from page 76)

Mansfield District Council’s three-step approach to coding for the town centre. View a copy of the code here.

Step 3: Site Specific Design Rules

CHECK if the proposed development is located within one of the 15 key development sites.

Read and apply SITE SPECIFIC DESIGN RULES.

Go to Part C: Detailing the Place

Chapter 7: Site Specific Design Rules (from page 106).

The Mansfield District Council Pathfinder team’s task of aligning their code to the local authority’s wider strategic objectives was made easier thanks to the recent publication of a town-centre wide masterplan and their vision statement for the town, Towards 2030, A Strategy for Mansfield. This preceded the production of their design code and already enjoyed support from both the council and stakeholders, which meant the coding team hit the ground running.

They did not take leadership support for granted, though, and they were mindful, for example, to express how they intended the

code to align with the corporate vision and objectives in reports to committees. This focus on the town’s wider strategic aims informed the code’s eventual set of townwide, area-specific and site-specific design rules. The tactic secured the full support of senior managers, which helped to smooth the adoption process.

Breaking down and working across the traditional silos within a local authority can be challenging at first, but with perseverance it can be done. The experience from the Pathfinder programme shows that the collaborative process is regarded as constructive and satisfying for participants. It was also thought to improve the quality and effectiveness of the code.

As the example of Mansfield District Council shows, it is particularly important to find an effective way to engage with corporate leadership and elected members. Indeed, this should be the first stage in any wider engagement. To do so, the Mansfield team spent time analysing both management and committee structures to identify the most appropriate directorates and service delivery teams to connect with. This will vary from authority to authority but could include senior managers in

Number of commonly engaged with teams and departments in developing the design code (out of 10 respondents) 9 Development Management

2

Other: Communications, Urban Design, Drainage, Historic England, Environment Agency

An overview of the departments and teams that most commonly informed the design code development of pathfinders

housing, regeneration, communications and community infrastructure, environment and neighbourhood services, public health and wellbeing, cultural services, adult social care and children’s services.

Collaboration requires everyone involved to keep the big picture in mind. When the Medway Council team first consulted across internal departments, they found it difficult to establish a collective vision. Although everyone had their say early on, they were only looking at the code from a siloed mentality, i.e. from the point of view of their particular division’s priorities. To be effective, the lead team realised they needed to instil what they described as a ‘a place mentality’ by focussing on the different area types.

On the City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Pathfinder project, the lead team quickly identified their most important targets for collaboration which included development management officers, the local plan team, highways and other departments like public health. The highways team were particularly important, contributing not only to the streetscape and public realm elements of the code but also helping to align the code to the sustainable transport initiatives that were being developed at the same time. The Bradford team also set up a technical group consisting of people from highways, transport planning, drainage, biodiversity, landscape and maintenance, to “drill down into the technicalities”.

You get better results when you draw on a wide local knowledge base within and outside the council. An important first step is to identify which internal departments and external stakeholders to involve and when you can do so, which you can programme into your overall project plan.

At every step, you should make the most effective and efficient use of participants’ time, which means tailoring how you engage with them. For example, you might consult external interest groups separately or in mixed workshops depending on your objectives.

Even before you ask for participants’ input, be sure to explain and promote the objectives of the code. When asking for input, give participants a clear brief about what you aim to achieve from the exercise.

At the start of the project, this is likely to be to gather information and ideas that will help you to establish the scope and main objectives of the code.

Once you’ve agreed the scope and are ready to develop technical content, a useful technique is to run thematic workshops, probably with a mix of representatives across different stakeholder groups.

Collaboration at the later stages should be used to test the effectiveness of the code with development management teams along with other select groups, such as local architects and developers.

The Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP) Council Pathfinder team used design charettes over a couple of days to bring officers, consultants and stakeholders together in a collaborative environment. These events included site visits and workshops, and included the participation of elected members, who were able to add detailed local insight.

While resource-intensive, BCP’s approach engaged stakeholders early in the process and helped to build relationships which,

in turn, accelerated the co-production of the code. The team considered their approach successful and had no hesitation in recommending it to others. As they said, “Hosting events is about quality of engagement and enabling a collaboration between different disciplines. Having people in the same room was very good and a positive platform”.

The Lansdowne Design Charettes encouraging collaboration between officers, consultants and stakeholders.

The Lake District National Park Authority wider public consultation used a video inviting residents to have their say.

The Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team used the Lake District National Park Partnership (NPP) – an established entity comprising 22 organisations representing the public, private, community and voluntary sectors – alongside local architects and material suppliers to develop the design code steering group. They then used this group to build a wide consensus on the content of their code at key stages of its development. As a ready-made and widely representative sounding board, the NPP was a particularly helpful forum for the Lake District team.

After first introducing the steering group to the concept of design codes, the

Lake District team used them to define core themes and areas of focus. They held four workshops in total to support the development of the code, including an introduction to codes and defining key priorities; a baseline review; a review of character and identity, and lastly a review of nature and sustainability in the context of design codes.

The Lake District team’s engagement strategy also included wider public consultation. Called ‘Have your say on the Lake District’s unique Design Code’, it was promoted with a video to encourage residents to share their views on the emerging design code.

This piece was written in collaboration with Peter Neal, an independent consultant and expert in planning, design, funding and management of green infrastructure frameworks, urban parks and the public realm. Peter Neal – Design Council

One of the primary users of design codes are development management (DM) officers. Codes help them to apply planning policy and make planning decisions. To be truly effective therefore, the production, adoption and implementation of design codes must engage DM officers from the start. Doing so ensures that the code works for DM officers and can boost their confidence in making decisions.

You should not forget, though, that design codes are used by many groups besides the DM team, including everyone else in the local planning authority, councillors, relevant external consultants, stakeholders and statutory consultees and members of the public.

Whether design codes are produced internally by the LPA or externally by consultants, they will be more effective if the people leading the work engage with DM officers early and consistently throughout the process.

Given their day-to-day work on assessing and determining planning applications, DM officers have a strong collective understanding of the local area and the nature of development proposals that come forward, especially in relation to where good quality outcomes are not being achieved. Their knowledge and experience can add considerable value to the process of developing and implementing a successful design code.

DM officers’ involvement is especially important when it comes to defining priorities and thus agreeing the design code’s scope. Understanding what is being coded – and why – provides a sense of clarity and certainty. This assures good outcomes and helps to manage the project’s limited resources. See also ‘From planning to execution’.

The Pathfinder projects yielded plenty of stories of successful DM engagement. At Gedling Borough Council, for example, the code’s objectives were not only clearly aligned to the local authority’s three corporate priorities – ’Characterful Gedling’, ‘Greener Gedling’ and ‘Connected and Healthy Gedling’ – but also closely mapped to national and local planning policies.

To be effective however, the code had to be useable and, as far as possible, easily managed by the LPA. This meant narrowing its scope to objectives that address the building types and most frequently encountered issues most in the target area. This meant focusing on alterations and extensions, small and large sites, formalising minimum distances between properties, and the wide variety of local character areas.

The project was led by the LPA’s policy team, who worked with external consultants to develop the code. Aware that their DM team had the most day-to-day experience of negotiating planning applications, the policy team implemented a system of checks to ensure that the code stayed true to its mission. Early versions of the code were piloted within the policy team and tested against current and former planning applications for improvements. The final

version was then shared with DM officers, who assessed the code’s usefulness and value in a similar way.

Consulting DM officers in this way not only ensured that the code worked but also secured their buy-in, dispelling cynicism and increasing the chances of successful implementation.

The Lake District team collaborated with their DM colleagues to help them to define the scope prior to consultants coming on board. Notably, they co-created a mind map that allowed them to narrow and clarify the key design issues, including window design, use of materials, natural light, and privacy. These were then set out in the consultants’ briefs.

Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council’s pragmatic solution was to let DM officers lead the project and write the code themselves. They were able to set their code’s main themes and priorities as a responsive set of practical answers to common day-to-day issues. Because the code aligned closely to their needs, the DM team bought into it strongly, easing the overall process.

Gedling Council’s code focusses on Characterful Gedling, Green Gedling and Connected and Healthy Gedling.

Your engagement with DM officers should be timely, consistent, structured and wellplanned. DM officers can be overstretched and might be reluctant to engage with the design coding process for lack of time and energy. This was true at Gedling Borough Council, where the lead team got the best value out of their engagement process by planning it in a way that respected and worked around DM officers’ heavy workload.

Before you engage with DM officers at any length, investigate how much capacity the team has and what options are likely to produce the best results. Communicating the long-term benefits is likely to help in persuading them to engage.

Some Pathfinders found it helpful to bring a select group of DM officers together as part of a working group for consistent monthly involvement. Structuring these meetings on specific themes was seen as a practical way to deliver good results. The DM officers involved were then able to disseminate news on progress to the rest of the DM team.

At the Lake District National Park Authority, one of the three DM officers on the project team was also assigned the role of design code ‘champion’ for the duration

of the project. Their job was to report back to the DM team and to represent the DM team’s interests in the name of improving the code’s useability. This worked well and, once again, helped to raise awareness about the code in the DM department. One person on the Lake District design coding team described it as “one of the most useful things that we did.”

As part of the engagement strategy, consider how you might enable collaboration across disciplines. Different parts of an LPA sometimes have conflicting objectives and can become quite siloed, inhibiting cooperation across departments and between consultees and decision-makers. For DM engagement to work and for their critical needs to be met, these barriers need to be acknowledged and overcome. For more, see ‘Bridging siloed working’.

The team at the City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council recognised this as an issue. To overcome it, they used a process called ‘consultation and peer review’ as a way to allow a deeper understanding of the primary stakeholders’ needs across disciplines.

DM officers had the chance, in a couple of iterations, to comment on initial drafts of the design code, which, as it turned out, was too long, overly technical, and not clearly communicated enough.

“They are working very hard to determine planning applications in a timely manner. We needed to be careful about how we engage with them at the right time so that we get the best value out of that engagement.”

Gedling Borough Council

The writing team gradually sought to address DM officers’ concerns by stripping back the detail to just the essentials, with the aim of producing a simple, concise planning tool that limited each coding section to a single page. For more, see ‘Writing for the reader’.

Once an engagement strategy has been agreed with the DM team, it is possible to plan its precise format.

A good approach is to use ‘workshop’ sessions. This is where DM officers test the emerging code against actual or mock planning applications and, in the process,

improve and refine its useability as a regulatory tool. In particular, these sessions should be used to interrogate the wording and illustrations in the code for clarity, simplicity and overall brevity.

Testing the code against an actual or mock planning application could involve using the content of the code to, for example:

Negotiate improvements to a scheme and include the findings in a succinct pre-application response

Write up a mock planning committee report with recommendations

Write up a mock delegated decision

Good practice shop front design promoted in the Lake District, in line with their design code requirements. View a copy of the code here.

On the Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder, a select group of DM officers agreed to join the design code working group. A small sub-group of DM officers subsequently tested the code, advising on wording, alignment with policy, suitability, and illustrations.

The engagement resulted in the code’s content being boiled down to four focus

areas based on the majority of application types they deal with: new homes, house extensions, conversions, and shop fronts.

Feedback from officers showed that the adopted design code was valuable, especially in helping them to prepare planning committee reports and decision notices. For more, see ‘Writing for the reader’.

Once the design code has been tested and adopted into use on live projects, it is helpful to offer DM officer training on how it is intended to be applied in negotiations and decision-making. For more, see ‘Laying the groundwork’.

For those closely involved in the code’s inception, such training will serve as a useful recap. For others, it is a learning opportunity critical to the overall success of the design code. It may also boost junior colleagues’ confidence in making decisions, as the Lake District Pathfinder project found.

Over the longer term, any training sessions can also serve as a forum for gathering feedback from DM officers, which should be used to improve and refine the code over time.

All projects encounter unforeseen challenges, and the Pathfinder projects were no different.

One of the most significant challenges was to convince DM officers that the point of the design code is to help them, not to inconvenience or replace them. Your engagement process should recognise the possibility of DM scepticism and aim to proactively and persuasively dispel it.

The policy team leading the Gedling Borough Council project invited the LPA’s head of planning and DM to a series of meetings to ensure the document aligned with expectations and the department’s needs.

The Gedling policy team also undertook an analysis of DM casework, revealing that 78% of refused applications were on the grounds of design. This allowed them to make a compelling case to the DM team that a code could ease the process of determining an application – without adding an extra tier of bureaucracy. Their analysis also revealed that the vast majority of cases involved alterations, extensions and the development of small sites. This insight allowed the policy team to sharpen the focus and user-friendliness of the draft code.

“Through the use of the code, new team members began to show an increased level of confidence in making more assertive decisions on design.”

Lake District

Engage widely across the DM department

Involve senior officers and head of planning to secure buy-in across departments

Engage as early as possible with DM officers and nominate a ‘champion’ and/or a small core team to ensure their engagement throughout

Draw up a list of common day-today issues faced and applications received by DM officers and use it to define the design code’s scope

Set up a detailed project plan and programme for DM engagement

Set up a working group early in the process

Test drafts of the code during the project using mock applications and case studies to ensure high quality and useable codes

Providing training for all DM officers to bring the wider team on board before adopting the code

This piece was written in collaboration with Peter Garitsis, an Urban Designer with over 20 years of experience in both the private and public sector on a wide range and number of development projects. Currently working for Swindon Borough Council. Peter Garitsis – LinkedIn

A key measure of success for a design code is that people can use it and feel confident doing so. Unfortunately, design codes can be both dense and detailed, and often need to satisfy the needs of very different audiences.

Successfully meeting the needs of these audiences means carefully considering the language and visuals you use, how much information you provide and how you structure the information. In short, it means that you must write for the reader, not the writer.

Several Pathfinders had to change tack during their development process to ensure that their codes would be both useful and impactful. It makes sense, therefore, to identify your target audiences from the outset and plan your outputs with their specific needs in mind. This will avoid abortive work and editing, ultimately making the process more efficient.

Design codes are relevant to a wide range of people, from professionals developing and assessing major planning applications to local communities with an interest in shaping the future of their places – and many others besides. Catering to this breadth of different needs can be a challenge.

Having a clear view on who will be using your design code early on in the process will help to ensure that the information you produce is clearly structured and pitched at the appropriate level. Not only will this improve the success of your code, but it will also help to ensure that your resources are used efficiently.

‘‘The key thing is to aim for just as clear and user-friendly a document as possible. Otherwise, design codes are not going to be a success.”

Bradford Council

The key external audiences include:

Design teams and agents. These groups will often be seeking more technical detail to inform the development of their proposals, and are likely to be comfortable with technical language, or even to prefer it. Precision and clarity will be key for these groups to understand the status of elements of the code. Providing checklists can help them to navigate multiple documents and requirements in a user-friendly way.

Homeowners. This group may wish to navigate their own applications through the planning system. However, they are often unfamiliar with the process and its associated technical terminology. They are likely to prefer shorter, more visual explanations and plain language.

Community members. The people in this group have a general interest in understanding how the places they live in might evolve. Rather than checklists, this group are more likely to prefer clear narratives and have an appreciation for baseline information and context.

Local and national landowners and developers. Although the people in this stakeholder group are professional, their perspectives might be different, particularly in terms of how the code relates to viability. A good way to engage with them to explore their needs is through existing forums. See also ‘Managing Code Creation’.

You also have a number of key internal audiences, including:

Development management officers

Policy officers

Urban design officers

Elected members

People that you might consult about applications, including colleagues in the highways or open spaces departments

For each of these groups, the test of your code’s useability will be directly related to how efficiently they can extract the information they need. For decision-makers, you must ensure that the relevant codes and visuals are easy to identify, interpret and apply. Ultimately, the useability of the code needs to impact both the inputs (planning applications) as well as the outputs (planning decisions). Assuming that the content of your code is informed by inputs from each of these groups, success will be down to how well the content is designed for your audiences. See also ‘Bridging siloed working’ and ‘From policy to practice’.

The first draft of Gedling Borough Council’s design code offers valuable lessons about the importance of writing for the reader. While the information would serve as a useful internal resource, the team quickly realised that it was unlikely to be practical or useable for audiences who don’t understand planning or design.

An analysis of the types of application they receive on a day-to-day basis revealed that 98% are for alterations and extensions or small developments of between one and nine dwellings, implying that the vast majority of their target audience would be likely to prefer the code to be shorter and punchier.

Describing this as “a breakthrough moment”, the Gedling team understood then that the information in the draft code would have to be edited down and repackaged for different audiences, with the detail and language modified appropriately.

In the end, they produced three versions. One was for people undertaking alterations and extensions (about 10 pages long). One was for those developing small sites (about 20 pages). And finally, one was for larger operators developing big sites. Across all of them, design principles were explained with clear diagrams rather than words.

Mandatory Requirements:

Design proposals must:

Mandatory Requirements:

Design proposals must:

• achieve a minimum back-to-back distance of 21 metres between homes up to two-storeys, avoiding interruptions in existing patterns of dwellings in how they are grouped and spaced This distance must be greater for homes with additional upper floors overlooking habitable rooms, or where changes in levels between sites lead to height differences between dwellings of at least one storey or more

• achieve a minimum back-to-side distance of 11 metres between homes up to two storeys This distance will need to be greater for homes with additional upper floors overlooking habitable rooms, or where changes in levels between sites leads to height differences between dwellings of at least one storey or more; and ensure that any windows on the gable end walls must be to non-habitable rooms only, obscurely glazed to a minimum level of Pilkington 4 and are non-opening unless the parts of the window which can be opened are more than 1 7 metres above the floor of the room in which the window is installed

Desirable Requirements:

Design proposals should:

• ensure that north facing properties are dual aspect, especially apartment units to ensure they benefit from sufficient natural light

Even with the most carefully considered content and structure, your code will benefit from testing with end users. This will help you to spot issues and refine passages for maximum useability. For some Pathfinders, the process led to substantial changes, saving them time and unanticipated expense later in the project.

Pathfinders used a range of methods to ‘road test’ their codes during the drafting process. These included in-depth workshops, training and briefing sessions with planning committee members, engaging with existing developer and stakeholder forums, and working directly with architects and agents to see how comfortable they were with using the code.

Typically, Pathfinders tested their codes once an initial draft was available. It is worth noting that these drafts were informed by inputs from earlier engagements with users, and so the project leads could be confident that their drafts, while far from perfect, were at least on the right track.

The testing phase had extra benefits. It updated user groups about how the code would work so that they could be better prepared once it was adopted. It also promoted the code more generally so that its adoption would not come as a surprise.

Some Pathfinders planned to maintain the ‘feedback loop’ of testing and refining their codes beyond adoption in a process of continuous improvement. As the team from East Riding of Yorkshire Council put it, “As things become more standard practice, we can add extra things and keep raising the bar.”

The East Riding Pathfinder team ran ten immersive three-hour workshops with their development management officers over two weeks to test their code’s useability.

Comprising of colleagues at all levels of seniority, the group was broken into smaller teams, each of which was asked to apply the code to a ‘guinea pig’ live application. About a third of the time was used to test the code on the application, with the remainder used for wider discussion about participants’ experience.

Clearly, the lead team learnt from participants, which helped them refine the code in several ways. They improved the imagery to better illustrate the code requirements, refined overly prescriptive codes and the compliance checklist to enhance useability, and combined placetype codes with authority-wide requirements to reduce the page count. It was also an opportunity to tell the participants how their previous inputs had been incorporated, which built confidence that participants’ needs were being addressed.

Digitisation offers a key tool for councils when considering the useability of design codes. The ability to navigate directly to the sections of code that apply to a specific site or application, combined with tabs of additional information for those that need it means that a web-based format can be well-suited to clear communication of design code information.

Trafford Council worked with their consultants to produce a digital platform for their design code that was easy to use. They worked with their team and framework consultants to prioritise the key diagrams and visual material that would help to communicate the code without becoming overwhelming. As a result, Trafford have received positive feedback from code users:

“We’re proud of how easy it is [to use]. We hope that somebody who doesn’t even know what a design code is could go on to this website and to the platform and look at the codes. They’re straightforward and clear.”

Trafford Council develop a digital design code (view here) to aid useability of their design code, making it easy for readers to select information based on their focus areas.

Feedback on how easy or difficult design codes were to use often came down to general best-practice principles. The checklist below summarises the most commonly received feedback.

Think about your intended audiences. Consider separating your final code into different versions for user groups with distinct needs. Making these decisions early will avoid abortive work.

Be concise. Even 50-page documents have received feedback saying, ‘This is too long’!

Tailor your language. Codes for homeowners should be simple and avoid jargon. People making larger applications are likely to be more knowledgeable and familiar with the planning and design process and so versions for them can be more technical.

People are put off by lots of text so, wherever appropriate, communicate visually through good illustrations and accessible graphic design. The NMDC includes examples of useful illustrations that are free to download. See also ‘Presenting Codes’.

Consider using compliance checklists. These have generally been well-received as a simple way to navigate code requirements by applicants and development management teams. Checklists can be included at the end of relevant chapters, or collated together in one place. See also ‘Laying the groundwork’.

Don’t swamp users in information. As the team at City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council pointed out, “Developers and development management officers just find it overwhelming, the amount of stuff to factor in. The key for codes is to stand out amongst this, to be a clear and easy tool to use so people can see why we are doing this”.

Don’t include non-essential additional information, such as background analysis, that can be consigned to separate documents. The main code can afford to be quite sparse.

The relationship between the main code and supporting documents must be clear and well-mapped. This does not mean that other documents need to be referenced in the code itself, but rather that the team managing the code should clearly understand how all documents integrate. Keeping certain information separate is a great tactic for avoiding duplication, possible contradiction or misalignment between documents.

Don’t feel compelled to digitise until you have a good draft in place. It will be important, however, to have a good data schema which can allow you to process and present information in different ways, including with future digitisation. If you do intend to release your code in a digital format, structuring your drafts accordingly is strongly advised.

This piece was written in collaboration with Holly Lewis, a registered architect and co-founding partner at We Made That. Holly has extensive experience in urban projects, including industrial intensification and high street regeneration. Holly Lewis – Design Council

Your design code will be more successful if you plan rigorously for its implementation right from the start. This entails identifying all the factors that need to work seamlessly when the different elements of your code come together and are put into practice in making decisions on real planning applications.

Partly, this preparation is about foreseeing the things you need to do during the project. These include three critical topics that are covered in our other materials:

From policy to practice – engaging constructively with your development management team;

Bridging siloed working – crosscollaboration with other departments, politicians and other key stakeholders; and

Writing for the reader – optimising your code’s useability through user testing, careful editing, and clear information design

More fundamentally, though, successful implementation relies on understanding how your design code fits in with the discretionary planning system. We will focus more on this in this section.

To carry weight in decision-making, codes should be produced as part of a local plan, or as supplementary planning documents (SPDs) or, looking ahead, supplementary plans (SPs). It will be for individual local planning authorities to determine which is the most appropriate approach for them, reflecting local circumstances.

The choice of whether to make your design code part of the local plan or to keep it as an SPD (or, in the future, an SP) is strategic. The Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team, for example, favoured speed of production and so naturally chose to adopt their design code as an SPD. The beauty of this, they said, is that they can review and update it flexibly without major interruptions to its use4

While design codes set out in SPDs carry weight in decision-making, they are not themselves policy. Therefore, where design codes are being prepared as SPDs, they should clearly link to ‘policy hooks’ set out in the local plan which provides greater weight in decision-making. Most local plans include design policy to which a code can be supplementary, and an emerging local plan should seek to adopt clear design policies to better suit an existing or future code, including new-style local plans as they come forward.5

4 Further details of the Government’s intentions around plan-making reforms set out in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023 will be published in due course.

5 Under the new plan-making system, where a design code is brought forward as a Supplementary Plan, this will form part of the development plan and serve as policy.

Where SPDs are prepared, clearly identified policy hooks ensure that your design code aligns accurately with policy, making it easier to ensure it is ‘supplementary to’ existing policy, not creating new policy. In other words, the policy sets out the overarching ‘strategy’, and the code is built from this by providing the ‘tactics’ for implementation. As the Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team found, having strong policy hooks helped them to assess each of the codes against their policy ‘to make sure that they were all compliant’.

While your design code must be aligned to existing policy, it can also influence the phrasing of policies in an emerging local plan. Knowing the detail of the design code makes it possible to write new policy in a way that strengthens the links between the two documents.

This is exactly what the Medway Council Pathfinder team did. Describing it as “a balancing act”, they were scrupulous in making sure that their emerging local plan contained the right kinds of policy hooks to support their design code.

Since Medway is currently at the Regulation 18 stage of adopting their local plan, they provided descriptive references to policy rather than specific policy quotes to avoid any problems with later adjustments to specific policies within the emerging local plan. However, at the Regulation 19 stage, it is anticipated that these references will become more specific as the Design Code is adopted. View a copy of the code here.

A design code supports development management officers in dealing with design matters during the determination of planning applications. A code that communicates policy positions unambiguously and is easy to use will help development management officers to apply policy consistently. As a consequence, it will facilitate and speed up negotiations and decision-making.

Another benefit of a code’s clarity (in comparison to design guides) is that it reduces dependence on the judgement of DM officers. This allows senior colleagues to be more efficient with their time and makes it easier for junior officers to develop the confidence to justify their decisions.

Lake District National Park Authority development management officers are already using their design code regularly in compiling reports and in negotiations with applicants, both at pre-app and at the application stage. Applications have been withdrawn and resubmitted as a result.

Reasons for refusals not only referred to their code, but also back to policy. This emphasises the value of unambiguous policy hooks as they make it easier for officers to track back to the parent policy from the design code. As the Lake District team said: “The policy hook still is what the development management team use to

justify their decisions. But the design code provides further detailed guidance about what that policy wording means”.

Adopting a new code allows you to “draw a line in the sand”, as Gedling Borough Council put it, marking a boundary between decisions made up to that point and all that follow. This is particularly useful in areas of poor quality or bland development. Adopting a design code allows you to apply new, higher standards, regardless of what was permitted before.

This will only work if applications comply with the design code. How easy it is for development management officers to make this assessment depends on the scope of the code, and to what extent the design code is expressed as unambiguous, binary rules.

You can best define your code’s scope by engaging with development management officers and cross-collaborating with stakeholders. While this produces good insights, not all of them will be directly relevant to your code, with the risk that you widen the scope and lose sight of your core objectives. If this happens, implementing your code is likely to be more difficult. As a general rule, the narrower your code’s scope, the more likely that the code’s requirements can be expressed in unambiguous rules.

At Gedling Borough Council, for example, the code’s objectives were not only clearly aligned to three of the local authority’s corporate priorities – ‘Characterful Gedling’,

A code that communicates policy positions unambiguously and is easy to use will help development management officers to apply policy consistently.

‘Greener Gedling’ and ‘Connected and Healthy Gedling’– but also closely mapped to national and local planning policies.

To be effective, though, the code had to be useable and, as far as possible, easily managed by the LPA. This meant narrowing its scope to objectives that address the Borough’s most prominent issues, such as the wide variety of local character areas and to formalise minimum distances between

properties; and building types, such as alterations and extensions, and small sites and large sites, reflecting the high proportion of applications received in these categories.

The project was led by the LPA’s policy team, who were writing a brief for external consultants to develop the code. Aware that neither they nor their consultants had day-to-day experience of negotiating planning applications, the policy team

“The policy hook still is what the development management team use to justify their decisions. But the design code provides further detailed guidance about what that policy wording means.”

Lake District

instituted a system of checks to ensure that the code stayed true to its mission. Early versions of the code were passed to development management officers, who tested their usefulness and value against former planning applications.

While it helps to set requirements in design codes as straightforward yes–no options, it is not possible to impose that rigour in every instance. Retaining flexibility in some respects, for example to enable development proposals to go beyond the requirements of the code, is therefore important. However, since part of the rationale for design codes is to reduce reliance on professional judgements in assessing compliance, you should aim to minimise the scope of this flexibility to make the code less open to interpretation. Where there is a risk that flexibility will

lead to ambiguous assessments, you need a way to resolve the uncertainty.

Medway Council Pathfinder team addressed this by developing a ‘code breaking’ policy regarding exemplary design, which is defined in the adopted SPD design code. Where a proposal does not meet parts of their code, or addresses policy matters in an alternative way, the proposal must undertake a considered and successful process through the Council’s preferred Design Review Panel. Utilising a traffic light system, the review panel then makes a judgement on whether the proposal demonstrates exemplary design by breaking identified coding requirements. If the proposal includes sections marked in red, it will be automatically rejected and requires additional reviews. All sections marked

green will garner support while sections marked in amber, require a nuanced response to determine whether code breaking is permissible.

Even if an application is assessed as compliant with the design code, the findings need to be weighed in the light of other policies and material considerations before permission can be granted or refused. The code supports an objective assessment of the design aspects of a proposal by setting out clear, preferably unambiguous rules that achieve policy objectives. This often improves development management officers’ confidence in taking design matters into account and giving them sufficient weight, to balance against other policies and material considerations.

The sheer variety of possible applications makes it difficult for your code to work as you expect in every instance. It should nonetheless raise the design quality of development.

Successful implementation requires you to bring your development management colleagues up to speed on using the design code and thereafter embedding it into their day-to-day practice.

This is not the work of a single person or team, but it does need positive management and engagement to ensure codes help design become a core part of planning by integrating high quality into everyday practice. As the Gedling Borough Council Pathfinder team said, the objective is “to embed your code in the planning application process” rather than keeping design assessment as a separate isolated exercise.

Integrating your code into daily practice involves allocating appropriate resources, ensuring cross-collaboration with other departments and outside agencies, prioritising development management time for useability testing, and integrating monitoring with other plan monitoring activities. Furthermore, successfully embedding codes in practice also relies on a number of things:

Training is a critical phase in implementing your code. As well as explaining how the code works and the processes for monitoring, you need to communicate arrangements for transitioning to it in dayto-day practice. This is also an opportunity to explain the code’s status, the weight of its requirements, and how to balance them against the other pertinent matters in decision-making.

Training should be carefully planned for maximum benefit. As well as ensuring that it is properly resourced, you should think carefully about the best people to deliver it. There are many options – development management officers, members of the policy team, in-house specialists, or even an external consultant. The point is to choose people who have an in-depth understanding of the legislative and corporate context as well as the detail of the code and any operational issues. For more information, see ‘Writing for the reader’ and ‘From policy to practice’.

You might also consider written guidance or videos that can be accessed outside of training sessions. The Pathfinders all took different approaches tailored to their local circumstances.

An important ingredient of implementation success is to advertise and promote your code to applicants.

At the very least, applicants should be made aware of your design code before they apply. Well-targeted information will allow them to take account of its requirements in a timely way, avoiding wasted time and resource.

Timely promotion communicates the code’s numerous benefits in terms of clarity and speed of decision-making, both of which are likely to be important for applicants. The more applicants know and understand, the smoother the implementation process.

On the Gedling Borough Council project, their website will be a critical tool in promoting the Design Code and

consideration is being given as to how best to ensure that applicants are directed to information on the Design Code before they are able to submit a planning application.

And Gedling are also seeing that the design code can be used more widely to promote the value of good design. The team’s promotional efforts extend to maximising the influence of their design code. Their view is that the spirit of the design code should be in all development regardless of whether the local planning authority has any control over it, even on permitted development. Making the point that, “It’s the extensions in your street that bother people the most”, their innovative message is that adherence to the code has the potential to not only promotes neighbourhood harmony but improves design and boosts the value of property, too.

Many of the Pathfinders, including Medway Council, are using checklists to help embed the practice of the code across everyone involved, from applicants to registration and development management (DM) officers, and extending to the preparation of the code itself.

Checklists can be used in the registration and validation process. By requiring an applicant to complete a checklist before an application can be registered, it ensures that applicants are aware of the code. Over time, as agents become familiar with the process and requirements, applications should become more compliant, reducing bureaucracy and speeding up the decisionmaking process. Completing the checklist is a requirement for the registration and validation of planning applications.

Checklists can also be used by DM officers in their decision-making process. However, even if the checklist submitted by the applicant indicates that the scheme is codecompliant, it is still essential for the DM officer to provide independent confirmation and analysis. If the code is written as unambiguous rules, a checklist offers a simple tick-box route to approval for a DM officer. However, in other situations, the quality of synthesis, outcomes, and other judgments must still be considered before approval can be granted.

Checklists can also play a role in checking the code’s clarity during its preparation. For example, the Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team found that its checklist was “quite long and ambiguous in places,” resulting in development management officers not using it. As mentioned earlier, this has been noted as a lesson learned, with a plan to improve the code’s clarity in future revisions.

This piece was written in collaboration with Penelope Tollitt, who has broad experience in local plans, urban regeneration, and master planning. She runs the consultancy Making Places Together, working with public, private, and third sector clients to achieve quality sustainable development. Penelope Tollitt – Design Council

There are numerous benefits to having a system in place for monitoring the performance of your design code. Monitoring provides evidence about what is working and what needs to be improved or refined. It should allow you to gauge the extent to which planning applications comply to the code as a proxy measure for improvements in design quality. Your monitoring system should also be able to track outcomes over time against the policy objectives that underpin your design code.

The accumulated evidence from the monitoring of your code should allow you to show positive gains against key corporate objectives and the extent of any returns on your investment in developing

the code. Moreover, you can demonstrate transparency and accountability by sharing the results of your monitoring with stakeholders and the public.

In short, the point of collecting this evidence is not just to know how the code is working but to use it in a cycle of continuous improvement.

The pathfinder design codes are still too new for their monitoring systems to have yielded enough evidence to assess their long-term success. However, the early signs are generally good, particularly the feedback concerning how useful design codes are in framing discussions during the preapplication stage.

“Monitoring helps us see what’s working and what isn’t, so we can make necessary adjustments and ensure continuous improvement.”

Lake District National Park Authority

Implementing an effective monitoring system for your design code requires early planning as well as good engagement and crosscollaboration with various stakeholders. For more information, see ‘From policy to practice’ and ‘Bridging siloed working’.

Ideally, you should be thinking about how you will check that desired objectives are achieved in practice from the very start of the project. Thereafter, that thinking should be integrated into every aspect of your design code’s development.

Only monitor factors that support your vision, including progress against your design code objectives, the impact in relation to wider corporate policies, and validation evidence. To do so, you must have baseline information against which to measure change. One key baseline measure is to know what percentage of planning applications, considering different development types and scales, are refused consent on design grounds. These refusals are time-consuming to both applicants and the LPA, and so a reduction in refusals is likely to be one of the chief objectives of a design code. Knowing the rate of planning refusals before the design code is adopted will help you to quantify the extent to which the code improves the situation.

You must also have defined your desired outcomes in a way that can be measured either quantitatively or qualitatively.

Data that you can usefully capture quantitatively (i.e. in numbers) include not just refusal rates but also many others, for example the number of people who use the code to make applications. If your code is web-based, you can also capture useful information automatically using web tools that record impressions, clicks, pageviews, unique visitors and bounce rates.

Qualitative data arise from analysing concepts that can’t be measured in numbers and so have to be generated from other sources. These include simple judgements or opinions (from surveys, perhaps) about whether, for example, the design quality of the areas covered by your design code has improved, or whether your local authority vision for an area is being achieved.

It helps to set the most critical objectives for the success of your code as key performance indicators (KPIs). KPIs are measurable criteria that allow you to monitor the main objectives of your code and can be structured as a checklist used to steer the development, implementation and management of your design code.

Another aspect to consider when developing a monitoring framework relates to the simplicity and ease with which it is possible to convert design coding objectives to measurable qualitative criteria.

The Gedling Borough Council Pathfinder project demonstrated the importance of upfront analysis to understand business as usual. The scope and development of their design code was informed by an analysis of development management officers’ case work. This analysis revealed that, over the four years prior to producing a code, 77% of refused applications were based on design grounds. This analysis helped to collect baseline data from progress that can be monitored and to

The task of monitoring the performance of design codes is made easier when the status of their requirements is mandatory – you must do something – as opposed to preferred – you should do something.

There are several reasons unrelated to monitoring why being clear in this way is helpful. Applicants know what they can or cannot do, a level of certainty that makes negotiations much more straightforward. Development management officers can also assess applications much more quickly, saving time and resource.

define the scope of the code, setting the agenda for reprioritising the design code’s objectives and, therefore, reconfiguring the draft that was current at the time.

This reality-check paid off. When the Gedling team’s development management officers tested the revised document, they were won over by how easily it could be incorporated into the application process and how user-friendly it was.

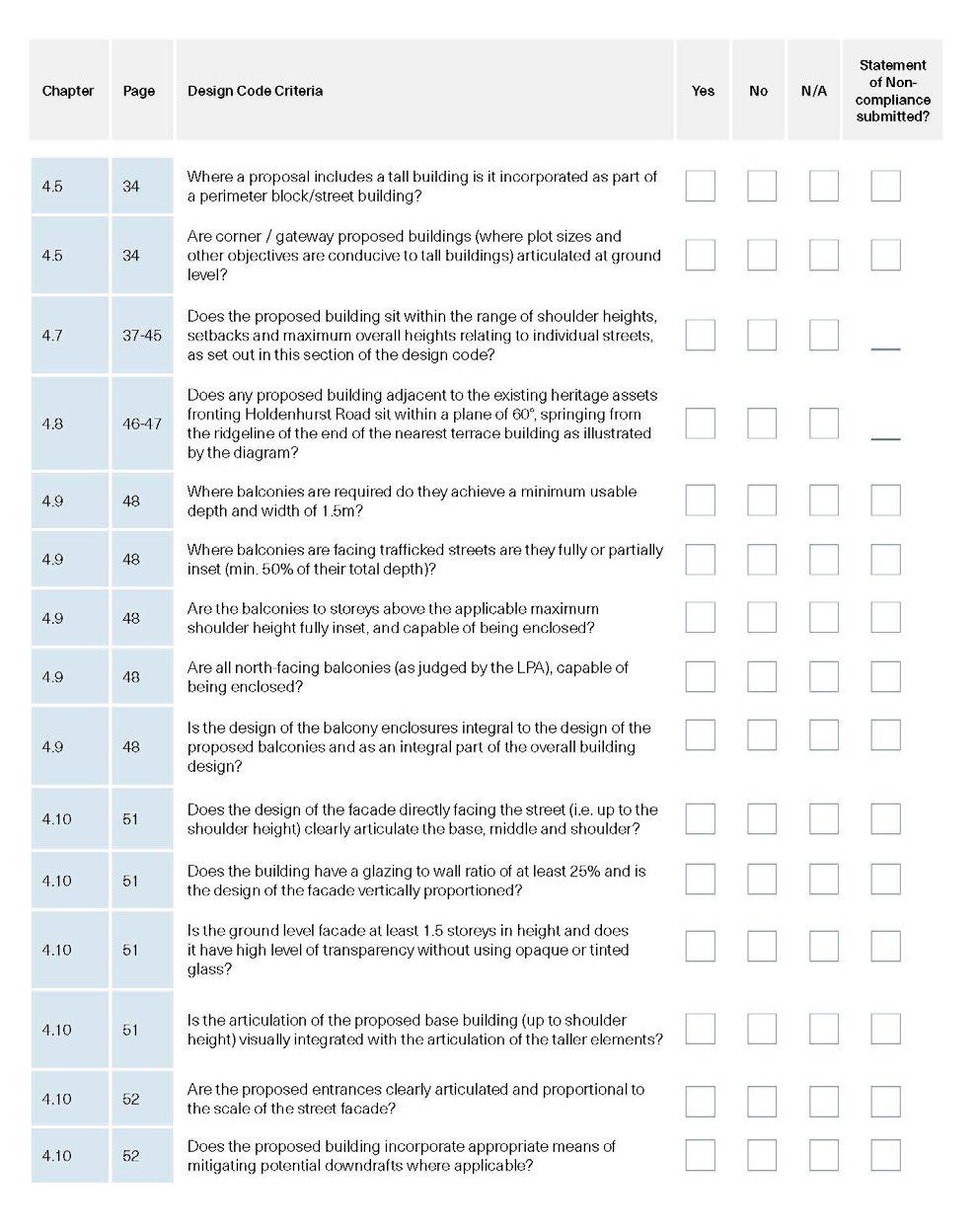

In terms of helping with monitoring, making as many requirements as possible mandatory allows them to be assessed in questions to which the answer is either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. These binary questions can then be compiled into a checklist that, once answered, allow you to see the extent to which applications meet the requirements of the design code. See, for example, the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council Pathfinder team’s ‘compliance checklist’ on page 50.

It is a very easy step from there to aggregate the yes/no answers in a monitoring system and use it to track improvements in the numbers of refusals on design grounds –one of the most important measures of a code’s success.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council’s Lansdowne design code compliance checklist features questions carefully designed to be answered either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, which effectively clarifies compliance.

This is exactly what the Lake District National Park Authority Pathfinder team has done. Using software called ‘Swift’ –already used by officers to feed data into the annual monitoring report related to the local plan – the team were able to monitor the numbers of refusals since the code was adopted. The monitoring system told the

LPA that, of the 42 applications they received in the first quarter of 2024 where the code had been applied, only five did not comply – and were refused. Having this monitoring framework in place allowed the team to track and quantify changes resulting from the adoption of the design code.

While useful, quantitative measurement of the kind described above lacks nuance, which is why it is worth backing it up with qualitative feedback (and, as with any statistic, careful objective interpretation).

The qualitative aspects of good design and placemaking – which are central to all planning policy – can only be assessed by proxy measures or in surveys, focus groups and interviews.

For example, in annual audits of the quality of the urban realm, city authorities in Melbourne, Australia, have developed a range of proxy measures to illustrate the continual improvements made relating the quality of life in the city, including yearly changes in: the number of cafés; number of front doors; number of pedestrians and cycles going through key gateways and public spaces; how people choose to spend their time in public spaces; number of trees; canopy cover; and so on. In understanding the existing context and measuring changes year-on-year, local

The bespoke Chatham area types illustrate a range of urban qualities that contribute to the success of each place, which may be measured over time. Images: BPTW

policies and initiatives focus on achieving positive change and enhancing quality of life improvements over time.

Inspired by this example, the Medway Council Pathfinder team incorporated these metrics into the design aspects of their own town centre code and are establishing a baseline for pedestrian activity, cyclists and trees. For want of time and resource, though, they have yet to establish a system to monitor its effectiveness.

Qualitative feedback is also important during stakeholder engagement and crosscollaboration and during testing and training phases. See also ‘Writing for the reader’.

Being clear about various code requirements calls for accurate use of language. In a code, you must use it precisely and consistently. Wording such as: ‘should’ , ‘could be’ , ‘consider’ and ‘typically’ introduce ambiguity and cannot properly be enforced, nor accurately assessed or measured in terms of compliance. It is vital in any design code to achieve clarity in its wording and imagery, as this translates to the qualitative requirements that are measured later.

Being clear, accurate and concise in the drafting of the code are pre-requisites for the creation and smooth functioning of a monitoring system. The reader must be able to distinguish between what is part of the code and what is merely guidance on how to meet the code. For related guidance, see also ‘Presenting codes’

Provided the objectives of a design code have been properly aligned to the local plan and wider corporate objectives through engagement and cross-collaboration, data from monitoring the code’s performance can be used to inform and update those higherlevel plans and objectives.

For example, the Medway Council Pathfinder team completed a digital 3D model of the area covered by their design code – the ‘Chatham Town Centre Massing Reckoner’ – to help to test the code’s parameters. This model is also being used to inform the emerging local plan by exploring options for the area and understanding the flexibility available for acceptable development capacity, based on insights from the code.

Best-practice principles for effective monitoring

Plan and resource a monitoring framework early: add monitoring criteria against design code objectives during initial visioning and scoping phases of developing a design code.

Create checklists for applicants and the development management review process.

Ensure metrics for monitoring are simple, clear and tied to specific outcomes.

Don’t rely solely on quantitative criteria: monitoring changes to the quality of the urban environment requires qualitative measurements as well as quantitative ones.

Allocate resource and build capacity: use a web-based format to gather basic usage data automatically. Otherwise, monitor change with simple digital tools, preferably ones that relevant colleagues are already familiar with from other contexts.

Prioritise what you want to monitor by understanding the code’s main objectives: tie your monitoring checklist to your code compliance checklist.

Engage development management officers in developing your monitoring framework and train them up on how to run the eventual monitoring system.

This piece was written in collaboration with Peter Garitsis, an Urban Designer with over 20 years of experience in both the private and public sector on a wide range and number of development projects. Currently working for Swindon Borough Council. Peter Garitsis – LinkedIn