Design for Planet Fellowship

Design for Planet Fellowship

2021 - 2022

Three Perspectives

The Design Council

Design Council has been the UK’s national strategic advisor on design for over 75 years. We are an independent not-for-profit organisation that champions design and its ability to make life better for all. Our work encompasses thought leadership, tools and resources, showcasing excellence and research to evidence the value of design and influence policy. We uniquely work across all design sectors and deliver programmes with business, government, public bodies and the third sector. Our Design for Planet mission aims to accelerate the critical role design must play to address the climate crisis.

Design for Planet Artworks

The Design for Planet Fellowship was funded by The National Lottery Community Fund.

Introduction

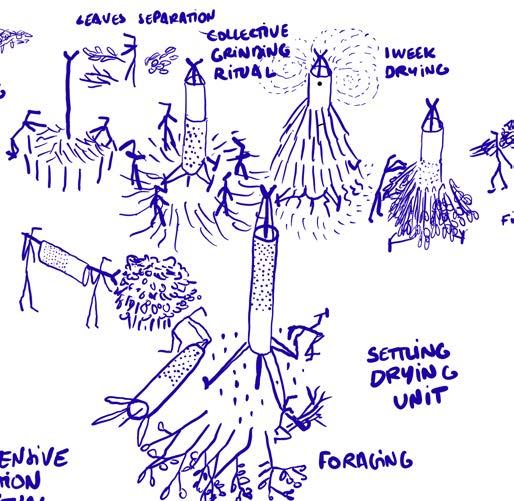

In December 2021, the Design Council launched the Design for Planet Fellowship: a proto-type programme that convened eight designers working across disciplines to explore emergent practices in systemic and regenerative design. Over seven months, the fellows undertook a collective enquiry to explore emerging opportunities for design to tackle the climate and biodiversity crisis.

Alongside this, the programme also explored how designers can act as ‘knowledge weavers’ experts at spotting the connections between different kinds of knowledges, sectors and industries, and who are adept at building relationships and new opportunities across these existing spheres in order to enable systemic change1. Knowledge weavers are often incredibly important actors within social and ecological activism, but their work is often under-valued, and their distinctive contribution to design unrecognised. In this, the project builds on Design Council’s recent Systemic Design and System-Shifting Design reports2.

The following three essays were co-authored by six of the Design for Planet fellows. They share critical perspectives on the role design can play in issues ranging from the rise of the digital commons, to declining connection with nature across communities. Throughout, they share examples of inspiring practice, and links to further reading and resources to continue your learning journey.

Author biographies

Professor Carole Collet

Carole is Director of Maison/0, the Central Saint Martins - LVMH platform for regenerative luxury set up in 2017. She is also co-director of the Living Systems Lab and explores how living systems thinking can inform new design knowledge. As an educator, she has pioneered the integration of ecological values in the creative curriculum at Central Saint Martins UAL by founding new courses such as MA Textile Futures in 2001 (now Material Futures), the world first MA Biodesign (2019) and recently launched the new online MA Regenerative Design (2022).

Sarah Drinkwater

Sarah is a community builder, entrepreneur and investor. Most recently, she built and led the responsible technology team at Omidyar Network, funding resources, tools, research, narratives and people working to design more societally beneficially tech futures. Before that, she was at Google building out physical community spaces for entrepreneurs, leading on the social layer on Google Maps, and advising startups on culture and community. Through Atomico’s angel program, she is an active angel investor in community-directed solutions.

Finn Harries

Finn is a British filmmaker and designer. He is the co-founder of Earthrise Studio, a digitial media company dedicated to communicating the climate crisis through research, design and filmmaking. He is currently studying at the University of Cambridge to complete an MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design. His research focuses on regenerative design and ecology. Finn has given talks at both TEDx and the United Nations in New York on the urgency for action on climate change and biodiversity loss.

Nat Hunter

Nat has worked in the field of sustainable design for 15 years as a practitioner and educator. She is also a trained CTI and Organisational Relationship Systems Coach and combines these trainings with her own experience as an entrepreneur and as an employee. She is a systems thinker, and brings her design skills, business experience, and coaching practice together in order to create and support change. She is very interested in how regenerative culture and behaviour within organisations can positively impact people, society and the planet.

Torange Khonsari

Torange is one of the original co-founders of the art and architecture practice public works. She has been a senior lecturer in architecture at London Metropolitan University since 2000 and is currently the course leader for post graduate programs and research on Design and Cultural Commons at London Metropolitan University. The direct two-way communication between academia and practice has enabled and enriched an exploratory environment within which public works is now operating.

John Thackara

A writer and curator, John is developing a Design for Earth Repair agenda for Tongji University in Shanghai, where he is visiting professor. The project explores design's contribution to ecological restoration, biodiversity recovery, and urban-rural reconnection.

Towards Regenerative Design

Professor Carole Collet, University of the Arts

London:

Central Saint Martins

Finn Harries, Director of Earthrise Studio

Introduction

In this short paper we want to reflect on how the creative sector can support a transition towards flourishing regenerative cultures . Design must shift from an anthropocentric discipline organised around linear economies, to become a more holistic practice that embraces living systems and circular economies, in order to restore the declining health of our climate, biodiversity and communities.

We often define design by what it delivers: a product, a service, a garment, a habitat, a system. What happens when the design output becomes a means to regenerate

our planetary health? Can fashion design help replenish our soils? Can architecture actively restore local biodiversity and sequester carbon? How can we transition to a regenerative design model that shapes a thriving culture where multi-species co-habit on a healthy planet?

This radical transition is urgent. The scientific evidence is clear: in the quest for perpetual economic growth, we have begun to destabilise critical planetary systems and, in the process, created profound social inequalities and injustice. The recent UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report reads as a “code red for humanity”, outlining our current trajectory towards more than three degrees of warming - over double the agreed safe average. While the “Living Planet Report 2022 “ by WWF revealed a 69% decline in wildlife populations between 1970 and 2018. It is clear designers must work not only to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,

but also to actively restore ecosystem health in order to mitigate the worst impacts of the environmental crisis.

So where and how can design act?

Since the Brundtland Report outlining the definition of “sustainable development” was published by the U.N in 1987, the creative sector has increasingly adopted sustainable principles. However, these widely differ from one creative discipline to the next, with very mixed results. The environmental narrative has evolved from “green design” to “responsible”, “zero waste”, “carbon neutral”, or more broadly sustainable design, with principles largely focused on limiting or reducing ecological damages. Fundamentally, these approaches fail to challenge the current linear global economic model at the heart of our environmental crisis and are therefore not fit to address our current planetary emergency.

The latest focus on circular design has helped introduce a step-change, where we recognise the finite dimensions of our planet and adopt nature-inspired circular systems. With circular design, material flows are redeployed, waste becomes a new resource, and toxic processes are eliminated, thus achieving a passive regeneration (by not extracting new materials or polluting natural resources).

With regenerative design (by default also circular), the focus - and starting point - is the positive and restorative impact of the biosphere and communities. Regenerative design is a holistic design process, often place-based, that supports conditions conducive to life. By incorporating principles of deep ecology and living systems thinking, regenerative practice can offer design propositions that provide for human communities whilst restoring ecosystems and climate. Instead of perpetuating an anthropocentric mindset which leads to

the depletion of our underlying life-support systems, we adopt bio-centric tenets: “regenerative design goes beyond sustainable and circular design principles to actively promote a multi-species approach in which humans and non-humans co-habit holistically.”

How do we transition to a regenerative design mindset?

Key Insights:

Ask different questions:

The Royal Society for the Arts (RSA) defines regenerative design as both a mindset and a new paradigm . Adopting this mindset means we need to review and evolve our design tools and methodologies. One of the first actions we can take is to reframe the starting point of the design process by asking questions of a different kind. If you are an architect, ask yourself: can my building improve the ecosystem around it? If you are a product designer, ask yourself: can my

Roker off Grid pods.

product help replenish the very materials it is made from? One key tenet is to give back to nature more than we take – so consider how you can design for reciprocity and for the benefit of other species. The key challenge is to embed this regenerative approach as the foundation for the design brief, not as a parallel or additional process.

Engage with living systems thinking

We live in highly complex interconnected ecosystems, organised in ecological cascades where every living being (including humans) has a role to play, from predator to decomposer. When these systems are out of balance, because they have been disrupted by the way we extract a material for instance, or by rejecting toxic pollutants in soil and water, then they are at risk of collapse. It is this way of thinking – remembering that everything is interconnected- that we need to practice and apply. We cannot interfere with one part of a system without considering the impact on the system as a whole. By adding, subtracting or replacing an element of the system we risk disrupting the whole ecosystem, even if we try to have a positive impact. This means that designers cannot act alone. We need to develop a network of stakeholders with relevant expertise in ecology and community building in order to be able to engage with living systems thinking and incorporate levels of eco-social complexity in the design process. Adopting living systems thinking in design means we need to consider the act of design as part of the web of life and think in terms of relationships and patterns as opposed to problem solving, novelty materials or innovative products. We also need to integrate multi-species thinking in our design process and question the values and impacts of our design proposals on other species who are part of the same web of life as us humans. This also includes adopting an intersectional dimension in our design approach to consider issues such as gender, cultural geographies and empathy towards all life forms.

Consider time and finance as key challenges

How do we build the true value of ecosystem functions into a product? How do we convince a client to invest in a regenerative approach? Whilst we might understand the urgent need to adopt a regenerative design practice, two key elements are needed: time and finance. Time to build a network of experts, to review our tools and processes and to think about how we can reframe our design practice at an individual or company level. Time to assess the beneficial impacts of our design propositions. This can take decades to be effective, especially when related to replenishing biodiversity. New courses to facilitate better training are emerging, whether academic or short professional staff development sessions, and the next generation of designers will be better equipped . However, for established designers, it is a matter of slowly building the expertise. Sometimes it is as much a matter of un-learning, as incorporating new knowledge.

The cost of the transition needs to be supported by wider economic and legislative frameworks. The Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) offers a pertinent new model that considers how we can thrive on this planet, and is beginning to be adopted by cities. Science based target initiatives help develop clear targets and goals which can be built within a company’s business plan. However one of the key challenges is that we have become used to operating in an economic system that does not include the value of the services of nature (such as pollination) in the final product. This will remain a key challenge until we can agree a new nature-positive international financial accounting system. “The worlds of ‘nature’ and ‘finance’ need to be better connected” and the tools and methodologies to incorporate the value of natural capital in our global finances remains an on-going topic for discussion in the UN annual Conference of the Parties (COP).

Art Gene’s Razzle Dazzle Braithwaite Bird Hide

Flat House: a case-study.

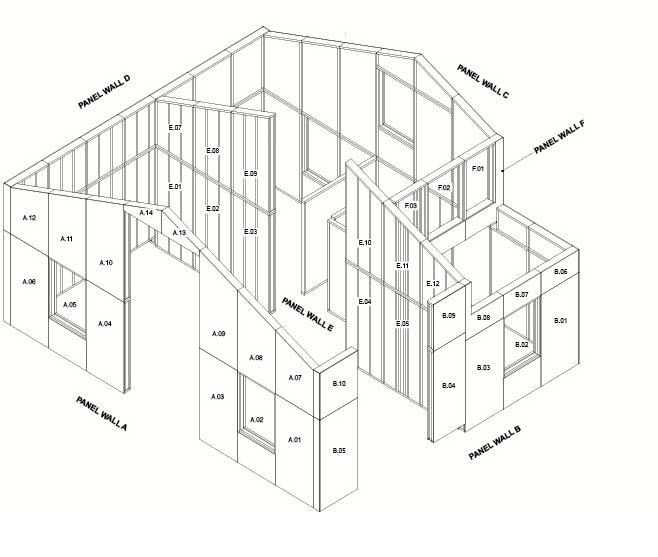

One example of a project that demonstrates a regenerative approach to design is Flat House on Margent Farm in Cambridgeshire in the UK. This architectural project attempts to address both the energy consumed and the carbon emitted during the construction process. In doing so, the solution proposed by the design team goes even further by supporting ecological and economic regeneration on-site through the use of a novel material and production process.

Flat House was built (in part) from the plants growing around it. The structure uses the fibrous hemp plant, both inside its timber framed walls for insulation and rigidity, and on its facade in the form of resin-based panels. To produce the material needed, the client cultivated 20 acres of hemp production directly on-site. This not only provided a local source of organic building material but a series of additional benefits. Hemp can be grown without the use of herbicides, pesticides or fungicides and has the capacity to bioremediate the soil by accumulating heavy metals in its tissues as it grows. It also sequesters a significant amount of carbon dioxide. According to the European Industrial

Flat House Photography by Oskar Proctor

Hemp Association one hectare of industrial hemp can absorb 15 tonnes of CO2. By growing hemp and using it in construction, the client was able to support the health of the soil on-site at the same time as reducing the embodied carbon of the building. The name Margent Farm references the “margins” around the hemp fields which are used to cultivate wild grass, flowers, hedges and fruit trees - creating a diverse ecosystem that supports local ecology.

Additionally, the research and innovation that came out of the design process created new sources of economic income for the client. Early on in the project the architect worked in collaboration with Cambridge University to develop a corrugated panel made from hemp and resin as cladding for the structure. This panel is now part of a set of products derived from hemp fibre and hemp oil that are sold by Margent Farm, helping them sustain their operations into the future. Finally, while the design project specifically investigated the embodied energy of the building through local material production, the operational energy has also been addressed through the installation of a biomass boiler, domestic wind turbine and on-site array of solar panels, keeping the overall carbon footprint of the building to a minimum throughout its life time.

Whilst this paper provides a very short introduction to regenerative design, we include a recommended bibliography below as well as key tips to begin your journey towards a holistic design practice conducive to life.

Top tips for designers

1. Use collaborative design as a means to weave knowledge across a range of socio-ecological expertise. Incorporate an ecologist and an anthropologist at the design briefing stage.

2. Design for reciprocity (what do you take from nature and what do you give back?) and with multi-species in mind.

3. Research and understand the value of local and indigenous knowledge as well as other ways of knowing and living.

4. Consider embodied knowledge by having conversations/design sessions in the place, not in the studio. Reconnect with the natural world and understand the impact of your design on other species and ecosystems.

5. Understand regenerative design is a journey and a practice. Take one step at a time - create the breadcrumb trail and stay with complexity.

6. Keep informed and develop a network of stakeholders invested in a regenerative future.

Further reading and resources

Bertalanffy, L. von. (2009). “General system theory: Foundations, development, applications.”(Rev. ed., 17. paperback print). Braziller.

Busby, P., Richter, M., & Driedger, M. (2011). “Towards a New Relationship with Nature: Research and Regenerative Design in Architecture.” Architectural Design, 81(6), 92–99.

Capra, Frijol; Luigi Luisi, Pierre. (2016). “The Systems View of Life. A Unifying Vision.” Cambridge University Press.

Clegg, P. (2012). “A practitioner’s view of the ‘Regenerative Paradigm’.” Building Research & Information, 40(3), 365–368.

Cole, R. J. (2012). “Transitioning From Green to Regenerative Design.” Building Research & Information, 40(1), 39–53.

Cole, R. J., Busby, P., Guenther, R., Briney, L., Blaviesciunaite, A., & Alencar, T. (2012).

“A Regenerative Design Framework: Setting New Aspirations and Initiating New Discussions.” Building Research & Information, 40(1), 95–111.

Cole, R. J., Oliver, A., & Robinson, J. (2013). “Regenerative Design, Socio-ecological Systems and Co-evolution.” Building Research & Information, 41(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/09613218.2013.747130

Design Council. (2021a). “Beyond Net Zero—A Systemic Design Approach.” Design Council. designcouncil.org.uk

Design Council. (2021b). “System-shifting Design: An Emerging Practice Explored.” Design Council. designcouncil.org.uk

Ichioka, S. Pawlyn, M. (2022). Flourish. “Design Paradigms for our Planetary Emergency.” Triarchy Press.

Fuller, R. Buckminster. (1969). “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth.” Carbondale.

Hawken, P. (2021). “Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation.”(First edition). Penguin Books.

Hutchins, G., Storm, L. (2019). “Regenerative Leadership.”Wordzworth Publishing.

Lyle, J. T. (1994). “Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development.” Wiley.

Mang, P., & Haggard, B. (2016). “Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability.” Wiley.

McHarg, I. L. (1992). “Design with Nature” (25th anniversary ed). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Meadows, Donella, H. ( 2017). “Thinking in Systems. A Primer.” Chelsea Green Publishing Co.

Raworth, K. (2017). “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-century Economist.” Random House Business Books.

Reed, Bill. (2007) “Shifting From ‘Sustainability’ to Regeneration”, Building Research & Information, 35:6, 674-680,

Sanford, C. (2017). “The Regenerative Business: Redesign Work, Cultivate Human Potential, and Achieve Extraordinary Outcomes.” Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Wall Kimmerer, Robin. (2013). “Braiding Sweetgrass. Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Penguin Books.

Wahl, D. C. (2016). “Designing Regenerative Cultures.” Triarchy Press.

Watson, J., & Davis, W. (2020). “Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism.” Taschen.

Power, Influence and Culture Change

Sarah Drinkwater and Torange Khonsari

Introduction

The joy of the Design for Planet fellowship is that it brings together leaders from very different backgrounds to build collective intelligence, find common ground and report back to our specific spheres of influence. Our workshop was framed as culture change, where values and norms can be interrupted and questioned. Culture change requires a shift in ritual or perspective at both an individual and a collective level. As well as where both interrelate and allow us to reimagine the collective in a way that creates space for individualism.

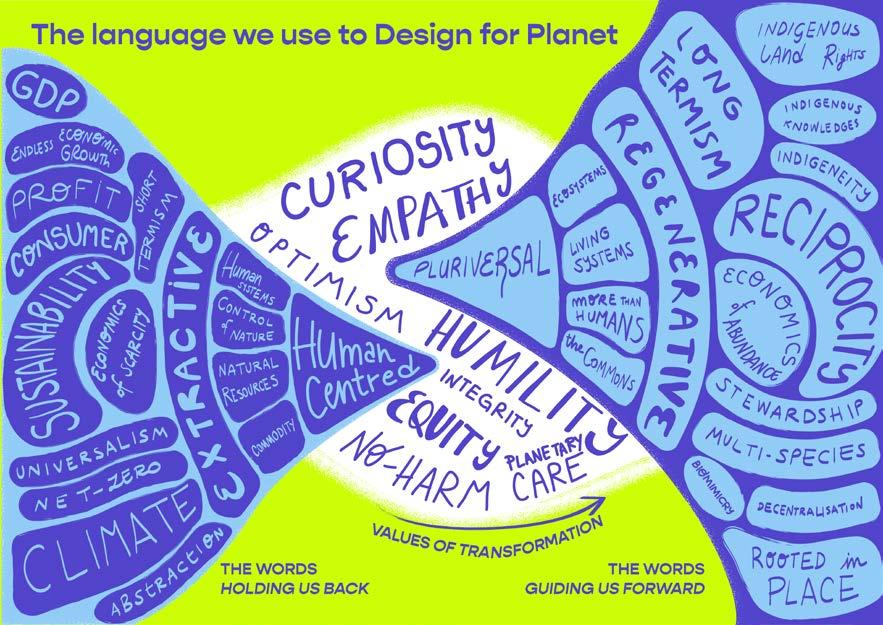

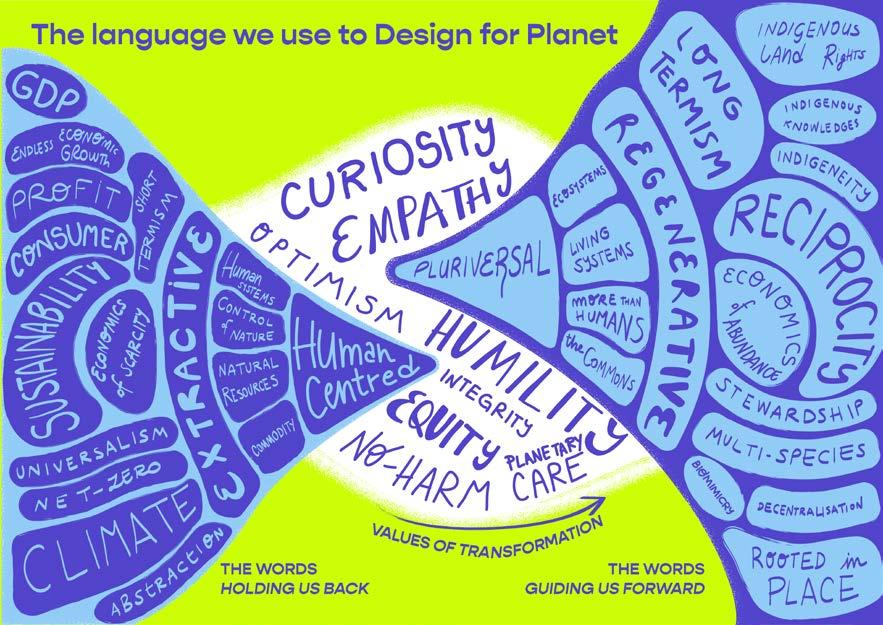

We took a different approach to the previous sessions, which were focused on regenerative design and ecology. This session was to systemically look at how values are created and the ways in which structures of power that go unnoticed can become obstacles to climate action.

Sarah comes from the world of technology, with a background in community-building and investing in early stage startups. To Sarah, “designer” often means the individual who is charged with creating the look and feel of a product. That sounds very simple but, of course, it isn’t. Not only does every choice have implications for the participant in or user of the product, but decisions taken at an individual product level can also have influence more broadly. Think of ‘dark

patterns’ - a user interface designed to subtly trick the user into doing something they might not wish to do, such as to share more information than they initially wanted. And outside of the specific function of design, the technology industry so often works to design for and not with people.

For the last few years, Sarah has been interested in helping technologists make better choices. That’s why she led Ethical Explorer, a set of playing cards designed to help people learn and consider challenges such as AI bias, surveillance, monopoly power and more.

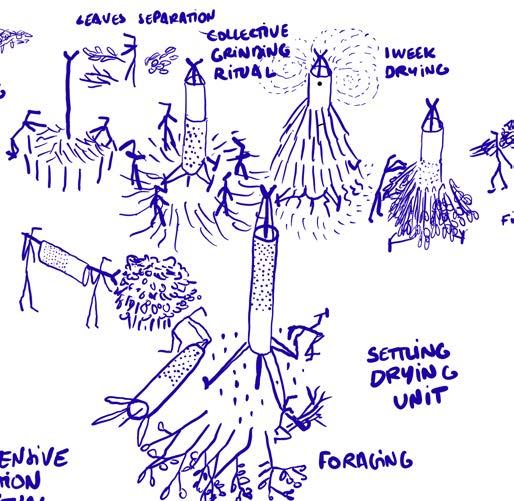

Torange has spent her career working one-toone with residents and communities in mostly deprived neighbourhoods up and down the UK. Her recent work has culminated in the introduction of her community engaged art, architecture and design projects into the field of the commons. She articulates the commons as the sphere of citizens whose logic is different to the sphere of the public (the state) and certainly the private (financial markets) with forms of practice that are ground up, self-determined, autonomous and care based (fig 1).

Design permeates every element of Torange’s work, ranging from system design, design

R-Urban_Poplar

R-Urban_Poplar

interventions, designing artefacts, institutional design and event design. In these design elements the functionality is not measured by pragmatic use but by the capacity to make change and shift hegemonic power. Power is pervasive and controls human action. Its use and abuse is normalised as the way our civilisation operates and behaves. It plays a great role in decisions around climate action. Torange has developed the professional course Design for Cultural Commons that is designed as a laboratory to deliver system change (fig 2). It maps systems of power as obstacles that need re-inventing. These reinventions provide shifts in cultural value as we use and work with them every day - a process called socialisation in social sciences.

We were brought together by our shared interest in the commons (specific communities) and public good (open to all). The commons are both the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a community, and the social practice of governing these resources, not by market or state but by a community of users. An emerging case study in how commons can be scaled up is in the rise of controversial Decentralised Autonomous Communities (DAOs), a term coined by Vitalik Buterin, the founder of Ethereum blockchain. DAOs have distinct goals, from funding public good to creating learning programs. But, at heart, they work to build the muscle in selfgovernance. Through building this muscle, we can create more resilient and regenerative systems. These systems are a fascinating technology in experimenting with relations of power more constructively.

In the workshop we wanted to explore ways to sustain the planetary commons and methods to scale them up. As described by Robert Mesle in his chapter “Relational Power, Personhood and Organisation”, power is usually conceived as unilateralthe ability to affect without being affected. Relational power oscillates power, with

R-Urban_Poplar

those who hold it creating an environment where everyone at one point has power and is powerless, including themselves. Centralised power is seen in most public and private sectors where relations of hierarchy can block power oscillation and democratic systems. Centralised power relationships put the right to decide on systemically fundamental values in the hands of the few, and this in turn sustains cultural values. The values that enable the top down power positions to be possible ultimately set the agenda. By visualising power relationships we can bear witness to both power’s destructive and constructive nature.

Spheres of influence

We observed that we sometimes used different words to mean the same thing in our different disciplines. So, before even getting into the core of our workshop, we wanted to help everyone to articulate both individually and as a group, our sphere of influence for culture change.

We asked all the fellows to look at fig 3, which is a diagram created from Kate Raworth’s 21st century priorities in “Doughnut Economics”, with an especial focus on the golden triangle of “the market — the commons — the state”. Here, the market represents those who work in the private sector, and the state those who work in the public sector . The commons represents the civic and community sphere. We asked all the fellows to articulate the sphere they primarily contribute to. This is an interesting exercise in becoming aware of how and where we contribute to society and the planet. The initial difficulty in trying to locate oneself in one or the other sphere was followed by responses that showed we cannot be purist about one sphere or another but are required to manoeuvre consciously across all three, with particular commitment to one in most cases. The question of what and who we are in service of and to was interesting, as it determines the culture and values we contribute to. If we are working in the service of the planet then extraction

R-Urban_Poplar

R-Urban_Poplar

of its resources is in complete opposition to the value of our service. Being conscious and critical of the sphere of value we are committed to, enables us to be less rhetorical about our actions.

One of the fellows talked about education not being on the list and yet it is one of the most important aspects of culture change. By broadening education to learning, we open up environments for culture change to places that we frequent every day such as projects we are part of, working environments, friendships we chose, neighbourhoods we live in, etc. In sociology, socialisation is the process of internalising the norms and ideologies of society. Socialisation encompasses both learning and teaching and essentially represents the whole process of learning throughout one’s life. It is a central influence on the behaviour, beliefs, and actions of adults and children. The diagram (fig 4) drawn during the session tries to capture where we felt culture change could happen.

One fellow used the word “pollinator or slime mould” as a facilitator of relationships between people across the three spheres. Another fellow, who also saw herself as a pollinator, talked about working with people in the private sector who are trapped on the capitalist, patriarchal hamster wheel where wealth accumulation is the only paradigm. She talked about placing them in other contexts to help them remember why they are here and connect them back to themselves, in order to break the framework we are socialised to believe as reality.

discipline and different contexts took years to bear fruit. You have to be persistent, patient and know that shifts in culture take time which can be framed as design practice.

Relational power as transformative tool

For the second exercise, we asked the fellows to think about instances of power relationships where a culture shifted or a power position was reversed.

Theories on relational power posit that you are more likely to build empathy in situations where power is agile and in flow than those where power is accumulated in the hands of a single individual or group. In the commons everyone, human and non-human, is high and low in terms of their position and power.

Getting people out of their familiar cultural environments, and into places that had managed to activate change, is powerful. One fellow described how by taking people to different places, from cities to farms, with a carefully curated participant mix of eco activists, farmers, artists and scientists created the cross pollination to imagine new realities. He said that the intersection of

The biggest challenge here is the use of the rhetoric of power-sharing for societal validation, rather than the practice of powersharing. The practice of relational power, like care, is embodied. Like a craft, it needs daily practice, development and designing. It is very hard to flex these new muscles and re-learn the value of being powerful through distribution of power when our society is dominated by centralised, hierarchical institutions and organisations. The design of systems where personal empowerment has a direct impact on collective empowerment enables healthy environments where the barometer of success is not individual power accumulation but a drive to heal the planet. If one practices both care and relational power every day in the home, with friends, at work and in the way we design the systems of future then nature cannot be seen outside those relationships. Nature does not become a detached problem, but the responsibility of us all as empowered carers whose motivation is not purely climbing ladders. Justice based ethics, as opposed to care

based ethics, promotes the individual rights of those who have a voice and have the resources to legally obtain one (where power is accumulated) and thus shifts our focus from caring to fighting. We would suggest every designer keep a daily diary of their power relationships and thinks about how to nurture or redesign them. We currently don’t have a blueprint for how this looks and need to share best practices with each other.

The mapping did not seek evidence or data but rather to visualise inequalities and the problems they pose to the non-human. One fellow talked about her frustration at having to spend time negotiating power with decision makers about the centrality of ecology in a climate emergency. Power is context related, so as an educator she resists overt power (although by holding the knowledge, you cannot avoid holding power). Students’ agency is paramount to ensure they gain the confidence to change the world in relation to our climate emergency. We need to equip them with the knowledge and power to become agents for change.

Another fellow talked about someone who held community values yet was unaware of inequality in power relationships. There was a conflict of power relations between this individual and the community of practice the fellow had nurtured in co-producing projects. The fellow created a bubble for the community to have a voice and decision-making power. This bubble allowed them to imagine different forms of living, doing and holding power. Through the exercise she realised that she had become a carer of collective power, protecting the group from imposed power.

Designers as empowered creators of such bubbles can allow others to think and dream alternatives and not be told what is reality.

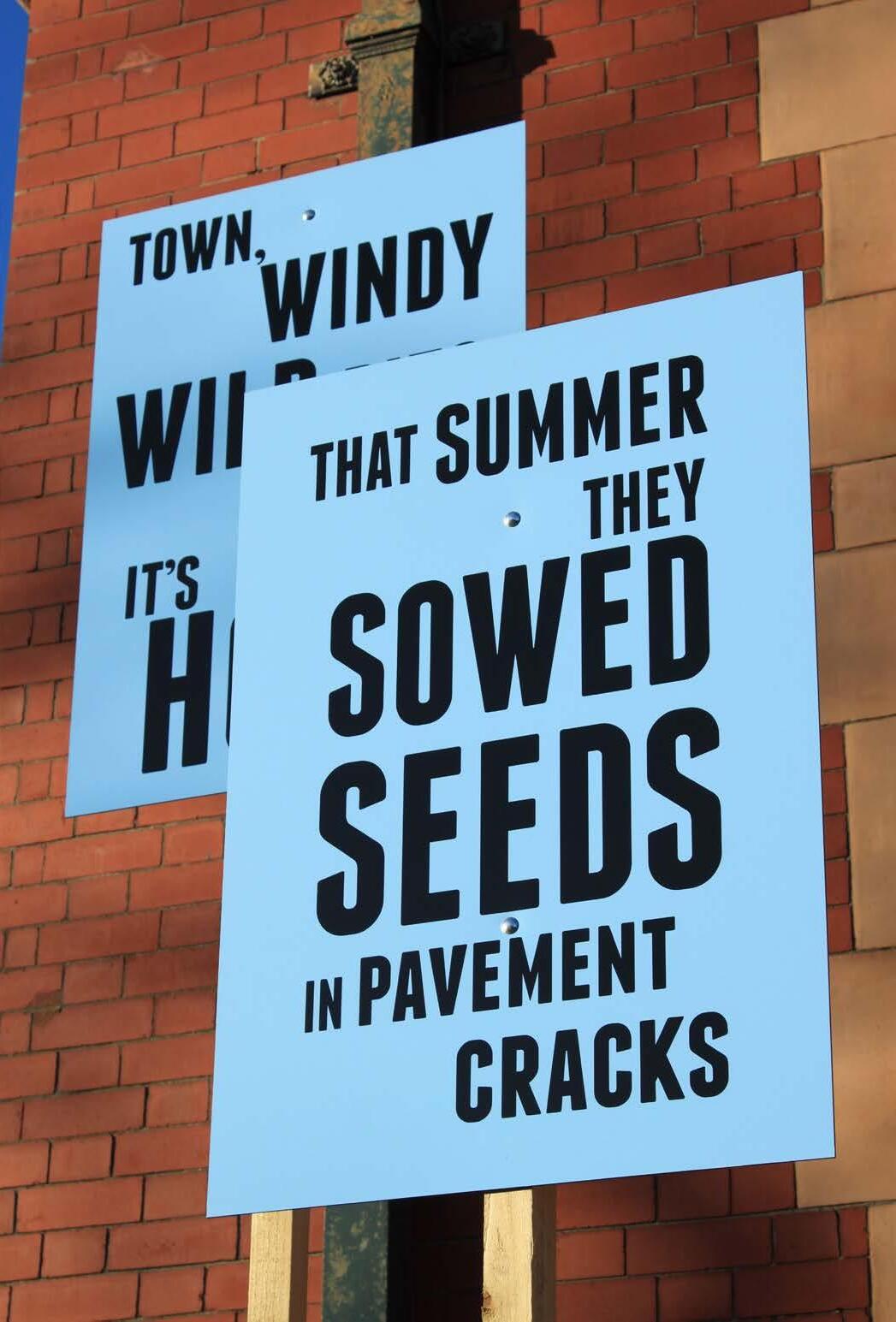

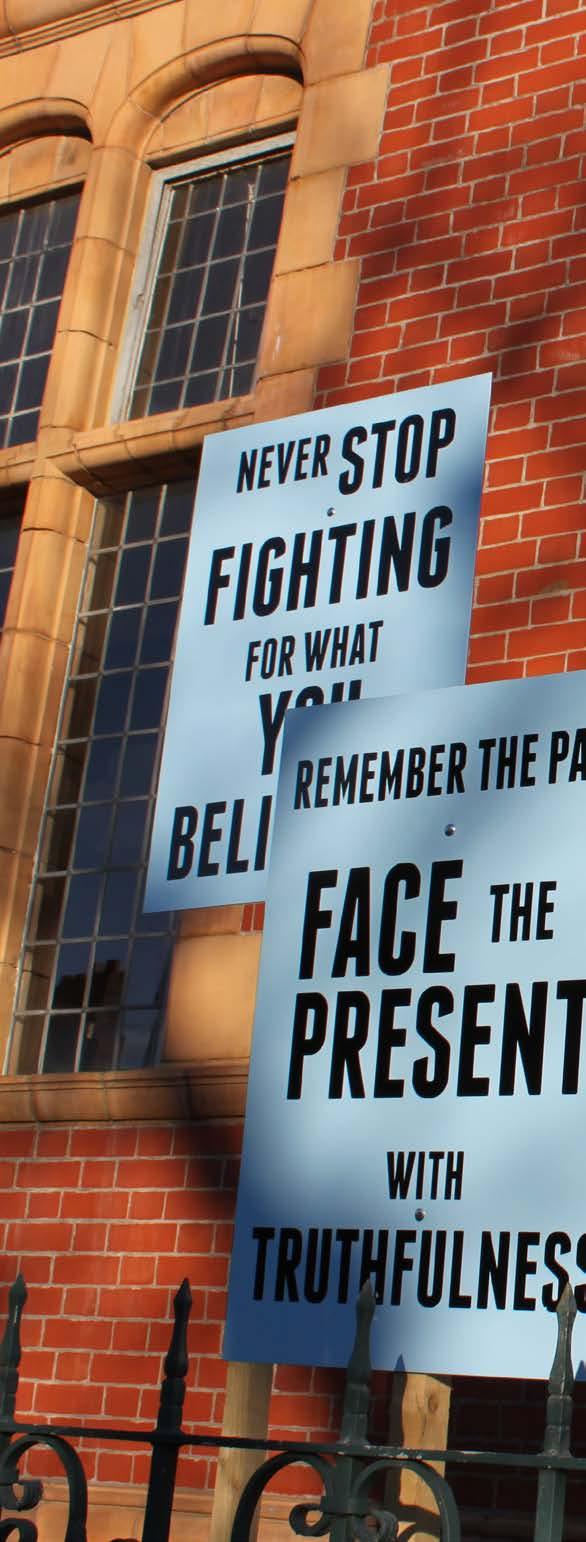

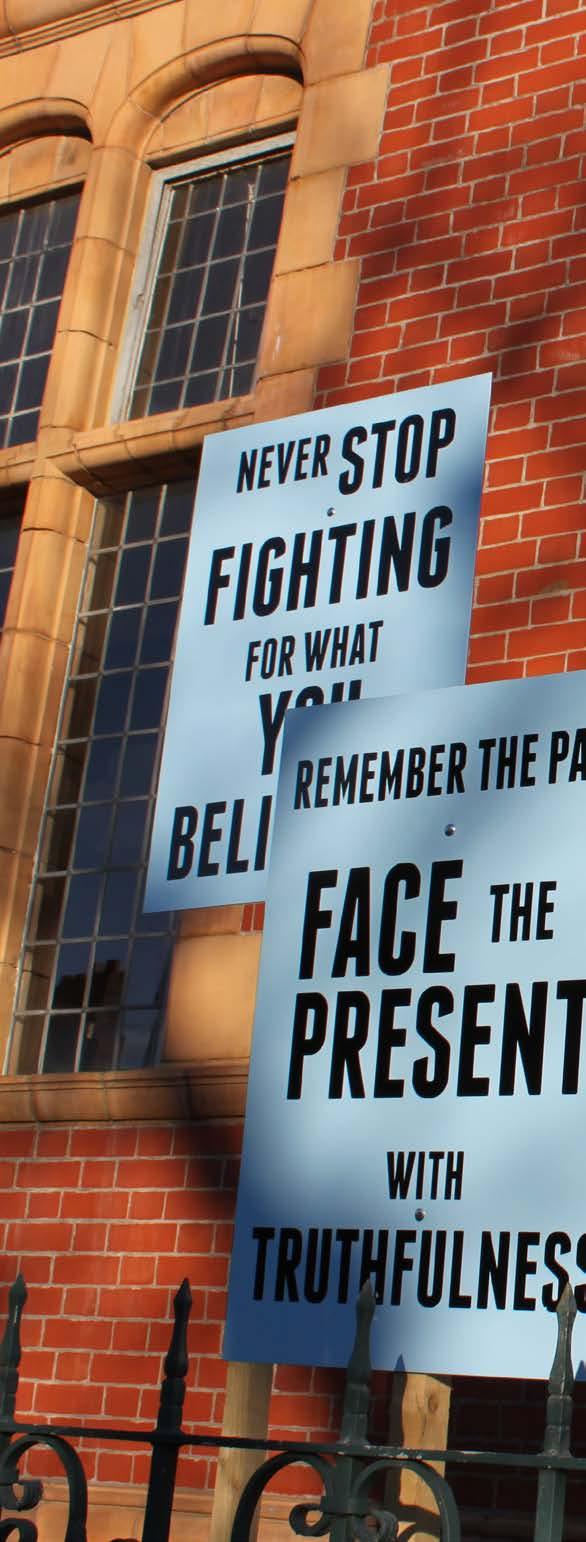

Another fellow’s story was about working with Extinction Rebellion and the power of direct action, even through small Promethean

acts such as holding up posters outside 10 Downing Street. The location brought home how the government dictates policies that respond to the climate crisis, which then trickle down to local government, agencies and business to be implemented. The people at the bottom are told how these policies should be implemented . They have no opportunity to engage, even when the policy is obviously flawed, creating complete powerlessness. This top down structure is not getting us anywhere in addressing the climate crisis.

Extinction Rebellion uses people’s assemblies, which are now being used at local government level. Individuals are randomly selected from a full cross section of society and brought into a room to make decisions. Given the most up-to-date science and statistics on the crisis as it

stands, they then have to make decisions in an emergency scenario, which are then mandated into law. We’re going to see these structures unfolding in different ways in different countries over the coming decades. We need new systems, skills and ethical practices that empower grassroots communities to make the changes that are necessary, without the pressure from invested interests such as industry.

Sarah gave an example of culture change within big tech companies like Facebook, Google and Amazon. People within these industries began to talk to unions and other community organising bodies about how to stand up to injustice. There were moments such as Google walk outs and the recognition of Amazon’s first union. Funds were raised to support whistle blowers of

fermeDesRenouees Outdoor

bad practice. Amazingly tech workers started to see themselves as employees with rights similar to the labour movement.

Again we return to the power of solidarity, community organisation and naming and shaming. The whistle blowing that shamed bosses in the media was a form of power that played against the enormous power of corporations and offered accountability within the private sector. It took employees years to recognise the difference between the publicly expressed values held up by tech companies, and the reality on the ground. Sarah saw employees begin to speak up internally and then externally to express their misgivings. This led to newspaper headlines, Congress hearings and, in more than one case, positive change and action within the company. The shift is still ongoing but, certainly, tech workers

are less naive about their employers now than they were five years ago.

Lastly, another fellow whose work is principally in policy-making talked about how power and culture change are intrinsically linked. Her role as an environmental strategist means she needs to comment on policies before they are ratified. She described how a policy was sent to her organisation to critique but by the time it had got to her it was a done deal and there was an acceptance that there would be limited challenge. Her power here was her expertise on the subject of the policy, but this was not enough on its own. She had to persuade her colleagues to look at the policy in detail to assess its flaws and collectively agree that it needed challenging. It was a huge undertaking for them to go back to a powerful client and admit

R-Urban_Poplar

Top tips to support system change in our everyday practices:

1. Possess self-awareness of one’s power and power relations engaged in every day

2. Critically interrogate rhetoric from action and impact

3. Engage in workshops, training and programmes that support system change design

4. Build in criticality in design, using care ethics and relational power

5. Produce the future new commons to strengthen citizen voice and protect our public goods

6. Support an economy that is holistic and for the common good

7. Act with agility when there is a fracture that offers the opportunity to make change

8. Become transformative practitioners

9. Build ecology, societal and climate care into the national curriculum

10. Become connected, outward organisations (solidarity movements) rather than inward enclosures (selfinterested)

this. However they collectively presented the challenges at the board meeting with success. As a result the client used them over and over again because they trusted their expertise and ability to challenge.

Interventions

We wanted to leave the workshop with a deeper sense of our collective power to act within the spheres of influence. This lead to the question of how we should intervene. Design interventions are both enquiry — the process of asking, listening and responding — and also activism. All of us are intervening in everyday experiences, whether at work, through cultural programs from museums to education, or through campaigning, policies, commissions and projects.

The more people who have power, the more we can scale up the impact. Culture change requires understanding what is possible and jolting people out of the familiar. We can’t think of power in a generic sense. We need to think about power in relation to those we interact with.

Conclusion

These examples, collectively, reminded the group how a collective can bring about powerful change even if they are small Promethean acts. The latter exercise helped an interdisciplinary team to speak more explicitly about power — a word and topic that had been less present during the fellowship. Power should be seen as a shared resource and a creative or

transformative tool, rather than a weapon to be wielded. Ultimately, culture change is about understanding human behaviours; how we can more effectively align and collaborate and how we operate in the commons that is our planet. We chose to bring the workshop back to an individual level at first so that we could see the overlapping communities we live and work in. The realisation of our incredible spread and reach heartened us, and made the notion of designing for planet seem a little less impossible. Each fellow works between worlds, acting as a translator or communicator across distinct fields. While the topic at hand seems more urgent than ever, we believe that to go far, it’s critical we first spend time building the muscle of collective understanding in order to unlock collective intelligence.

Outdoor

fermeDesRenouees

Case Study: Public Works

This relational power case study, Public Works, is a not-for-profit critical design practice working across architecture, art and performance, and has been an institutional design project itself. The below description includes reflections from a collaborator Rakan Buderi who described Public Works in 2015.

Public Works is a cultural practice embedded within the relational theories of French art critic Nicholas Bourriaud who, in the mid1990s, was involved in the aesthetic of social relations and spatial contexts within the public arena, rather than those of private and individual space. In contrast to object orientated art or architecture, the relational practice of Public Works encourages models of alternative sociability and the production of social spaces where the space is a social product. Participation is elementary to relational art and architecture and defines its political nature, with citizens invited to form a responsive community in relation to the practices carried out. By attempting to create relational architecture involving people from the outset, Public Works cannot frame their practice as a service and thus move away from traditional power relationships. The collaborative nature of Public Works with external practitioners and communities means they need to be flexible and reactive, tailoring projects to fit into what is happening around them, rather than imposing ideas on situations. This moves into actioncentric design methods, rather than the conventional linear ones found in traditional practice. Architects are normally aligned with top down power, being bound up in a restrictive system due to financial pressures. However, the shift to incorporating other disciplines with architectural practice (not in service of) within a network of collaborators, provides the support and financial ability for the practitioners to take increasingly ethical decisions. The practice’s methods revolve around models of participation, listening

and openness which is in opposition to the capitalist system of competition and metrics. The methods focus on models of common space and its empowerment through selfmanagement. Sometimes this takes the form of permanent or temporary interventions in a space but also includes discussion forums, objects, one-to-one actions, zines, and participatory programmes and events, all of which enable engagement, collaboration, relational power and knowledge transfer along with providing platforms for dialogue and for the public to find common ground within the city. The practice’s projects act to demonstrate how physically separated sites are connected within larger social, emotional, ecological and economic networks. In collaborating across disciplines and civil society, Public Works has been able to engage art, design and architecture as part of a social process with political undertones.

The processes have been experiments for rethinking ways that cities can be inhabited and civic life nurtured and formed, collectively.

From 2016 the practice became aware of its role as an outward looking organisation and applied the experience of building social relations to re-design its governance. Public Work’s organisational form intends to distribute power away from its founders and share it with internal members who also create value within it. Hence the decision by the founders to share the position of company director equally, giving equal rights and freedom to all its members to pursue individual interests, pitch for work they are interested in, build their client body, take holidays when needed and manage the budget to pay themselves as they see fit (within an agreed daily bracket), as long

as 20% of all income is contributed to the collective pot. Whilst the collective pot becomes the common resource of Public Works, the individual members set their own budgets for their labour, based on the time they need to deliver the projects. This structure means a move away from accumulation of profit by the original founders to the re-direction of profit as investment into the commons. This model contributes to the characterisation of the work environment as a forum for exchange which does not focus on power and wealth accumulation. The culture this aims to set, and the incidental learning of all its members, become embedded in equality, trust, commitment and care whilst still maintaining the payroll structures of PAYE and pension contributions.

fermeDesRenouees Outdoor

Nature (re)connection for designers

Nat Hunter and John Thackara

Why was this our theme?

Nature reconnection shifts our understanding of our place in a living world. It reminds us that all life is interconnected, and equally important. This awareness is the heart and soul of our work on systems change.

“The destruction will stop when we see nature differently, relate differently, understand our purpose here differently.”

When the Spanish philosopher Raymond Pannikar wrote these words in 2010, connection with nature was not a priority for the design world. The launch of “Design for Planet” is a signal that our culture is shifting. The idea is gaining hold that our highest purpose is to create conditions for life.

If this new mindset is indeed emerging, a novel question arises: under what circumstances would the majority of designers design for all of life, and not just human life?

When Children Rule the Worldenvironmental workshops

Our answer to that question - our theory of change - begins with an observation: telling designers how to think, or what to do, is counter-productive. What’s needed is less advocacy, and more embodied experiences of being connected with all of life - and on a mass scale.

Our theory of change then builds on some good news. Millions of people - of all ages and backgrounds - are already seeking a connection with nature through diverse practices. We are not starting from scratch.

Nature reconnection is not experienced in the same way everywhere. People understand the word ‘nature’ in diverse ways. For some, connecting with nature takes place in a distant natural park. Others find meaning engaging with weeds in an urban brownfield site. The relationship people have with nature - or not - is shaped by class, culture, lived experience and identity.

Access to nature can be a political issue: not all communities have equal access. Similarly, not everyone experiences nature as benign. Some people fear nature, and find security in being separated from it. Others perceive the presence of nature as disquieting evidence of disorder.

With these caveats in mind, we believe this flourishing ecosystem of projects represents three opportunities for design.

First, by exploring myriad experiences for themselves, and finding what works for them, designers can expand their understanding of the interconnectedness of life.

Second, they have the perfect skills to broaden and diversify the number of people connecting with such transformative experiences.

8 Words for Barrowmittens

And third, they can help their clients and employers too - by connecting them with local projects that do social and ecological good.

Connection with nature is also an essential complement of the Design Council’s work on systems change. We believe that by making designers curious about “what we’re inside of”, in the words of Nora Bateson, they will be motivated to explore a whole-systems understanding and experience of the world.

As a complement to systems thinking, ecological design practice brings designers into contact with real-world biotic communities

- from sub-microscopic viruses, to the vast subsoil networks that support trees.

Learning about these worlds - at different geographical and temporal scalesalso brings designers into contact with novel disciplines: climatology, hydrology, geography, psychology, history and many more. These new disciplines and actors enrich the systems change ecosystem that designers are now part of.

We believe that a combination of the latest insights of systems thinking and complexity science, together with wisdom traditions

Barra Nite life

from other places and times, will help designers connect with living systems emotionally, as well as rationally.

Our desired outcome

Life-first design is not yet mainstream, and we wanted, in this workshop, to understand two things. What kind of nature connection activities work well for designers? And what it would take for them to have these experiences on a mass scale?

Key insights and takeaways

Nature connection has significant potential

for policy makers engaged in system change work. It can be a cornerstone of the move towards rights to nature access for all.

The contribution of nature experiences to health and wellbeing is confirmed by a growing body of evidence. Public investment in social prescribing is an affordable way to enhance public health. Investment in skills training can benefit not just the voluntary sectors already doing this work, but also site owners such as farmers and foresters.

Enabling nature connection is a relatively easy way for companies to meet the demands from their staff, and clients, for meaningful climate action.

Connecting with nature is a journey, not an action. When Copernicus proved that the earth revolves around the sun rather than vice versa, it took a further 100 years of resistance and argument before the news really sunk in. On such a fundamental issue as our place within nature, learning to think and feel our way into an ecological world view, and daily life practice, is a lifelong journey.

We are not starting from zero on this journey. It is now 50 years since “Limits to Growth” was published. Today, nature reconnection is a fast-growing global phenomenon.

Connecting with nature is as much about attention, as it is about action. A culture of attentiveness to nature is the best way to sustain a sense of ecological responsibility towards future generations.

Connecting with nature is ideally experienced in places. The natural world - including urban locations - is a site of experiential learning, and a teacher, in its own right. Lifelong learning about interdependence, interconnectedness, and diversity should be situated learning.

The Me, and the We, and the Both, matter equally.

Cognitive Justice means recognition of the plurality of knowledge, and the right of the different forms of knowledge to co-exist. It’s important to understand different ways of knowing, of communicating and of what intelligence might mean. These include embodied intelligences that are shaped by place.

Time to think: we all need to slow down in order to experience the world from an embodied place. Workshop participants thanked us for providing space to hear themselves think, and to take time to connect to each other, and reflect together on what they might want to do next.

Barra Nite life

A case-study example from the workshop

Our workshop explored our feelings about our connection to nature. Without even venturing into the outside world, we were able to engage with emotions which lay beneath the surface and turn them into meaningful action.

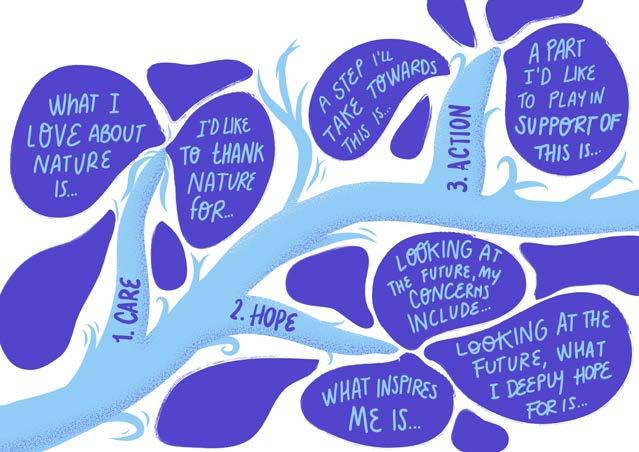

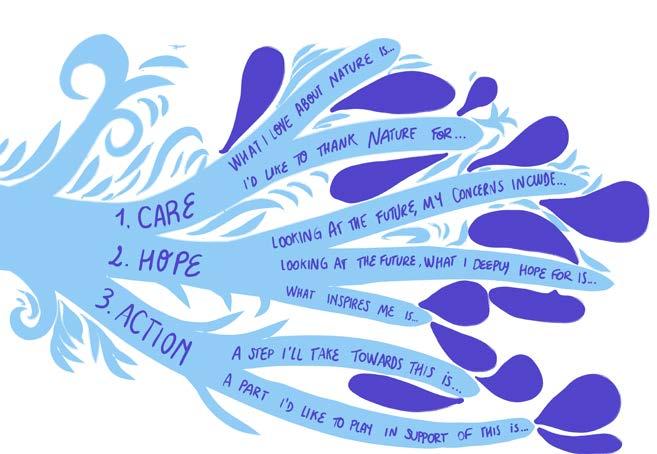

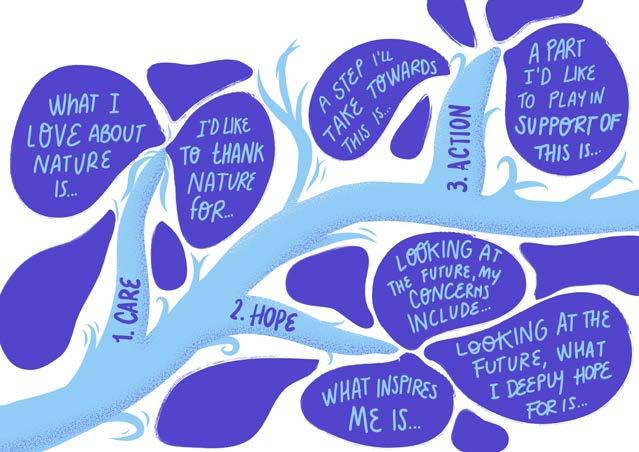

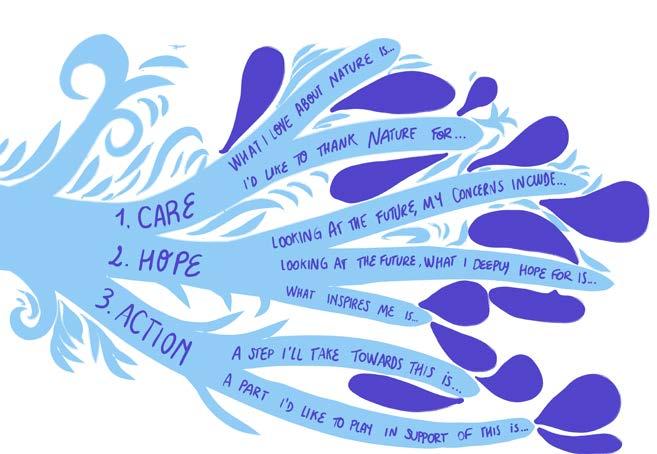

The main exercise of our workshop was based on Joanna Macy’s “The Work That Reconnects”. This particular exercise was based Macy’s idea of “Active Hope” - a practice we can apply to any situation.

The practice starts by taking a clear view of the reality we face, and what we feel about that. We then identify what we hope for -

in terms of the direction we’d like things to move in, or the values we’d like to see expressed. Finally, we commit to take a step, however small, that moves us or our situation in that direction.

The workshop was in Zoom, and we created breakout rooms of two people. We each took it in turn to speak for a minute, prompted by open sentence starters. Open sentences are prompts: there is no right answer. Participants were encouraged to just feel into the first thing that comes into their head and say it aloud.

10.EXTREME VIEWS - MILLOM - with rose tinted glasses. Photo Maddi Nicholson

10.EXTREME VIEWS - MILLOM - with rose tinted glasses. Photo Maddi Nicholson

The seven open sentences were as follows, with participants taking a minute for each sentence before swapping over.

1. What I love about nature is ...

2. I’d like to thank nature for...

3. Looking at the future we’re heading into, my concerns include...

4. What inspires me is....

5. Looking at the future we’re heading into, what I deeply hope for is...

6. A part I’d like to play in support of this is...

7. A step I’ll take towards this is...

At the end of the exercise there was a fiveminute period for solo reflection. We then came back to the group and shared our thoughts for another few minutes.

The overwhelming feedback from the exercise was one of gratitude. Participants cherished the opportunity to stop, feel and think. The open sentences created an intimate space in which we listened to ourselves think and feel, and witnessed our partner doing the same. It felt spacious and insightful, creating clarity about a step that we each individually wanted to take. The whole process took only 30 minutes.

When we started planning our workshop, the idea that designers might embrace the idea that all life is interconnected, and of equal value, seemed far-fetched. A few weeks later, this awareness felt like a very natural part of our work on systems change.

Further reading and resources Work That Reconnects Network

Books, lectures and debates are not enough by themselves. Based on systems theory, spiritual teachings, and deep ecology, The Work That Reconnects is a pioneering

Top-tips for designers

1. Go on a walk. Pay careful attention to nature. Find a ‘sweet spot’ you can easily return to. Consider adopting a weed.

2. Focus on connections in systems, rather than discrete elements. Consider ways to enhance relationships between people, place and nature.

3. Self- awareness and self-development are a key part of all of this - but we don’t have to do this work alone. Find a coach, a guide or a journey partner.

4. Embodiment is not so easy for those among us who were raised in a culture that praises left brain rational thought and dismisses intuition, hunches and inspiration. Don’t be discouraged! It may take a little perseverance and practice to relearn how to connect to and trust those parts of ourselves.

5. Create space and time in your life to be away from the computer, preferably amongst nature - however tiny.

form of group work that demonstrates our interconnectedness in the web of life. Its methods are described in “Coming Back to Life”. workthatreconnects.org

Emergence Magazine practice booklets

Emergence Magazine’s practices are simple but meaningful ways to connect with the living world:

emergencemagazine.org/print/practicebooklet-vol-1-2

emergencemagazine.org/practice/ befriending-a-tree

emergencemagazine.org/practice/

listening-for-silence emergencemagazine.org/practice/ navigating-a-shifting-world emergencemagazine.org/practice/ arriving-with-every-step emergencemagazine.org/practice/ listening-to-the-language-of-birds emergencemagazine.org/practice/beingwith-the-dark

“Kinship: Belonging In A World of Relations”

From The Center for Humans and Nature, a collection of essays, interviews, poems and stories of solidarity that highlight the interdependence that exists between humans and nonhuman beings. humansandnature.org

“The Web of Meaning”, Jeremy Lent

Once we shift our worldview, another world becomes possible. “The Web of Meaning” offers a coherent and intellectually solid foundation for an alternative worldview based

on deep interconnectedness, and shows how modern scientific knowledge echoes the ancient wisdom of earlier cultures.

“Ways of Being”, James Bridle

James Bridle is an artist, technologist and philosopher. This book explores different kinds of intelligence - plant, animal, human and artificial. For many people, the book transforms their understanding of humans’ place in the cosmos.

“Sacred Instructions”, Sherri Mitchell

“Sacred Instructions” is a narrative of Indigenous wisdom. It provides a road map for the spirit and a compass of compassion for humanity. Sherri Mitchell is an Indigenous elder and also an attorney and activist. Her book is about decolonisation and recovery of an Indigenous worldview.

“Braiding Sweetgrass”, Robin Wall Kimmerer

Potowami professor of Botany, Robin Wall

Kimmerer’s hugely influential book describes the role of Indigenous knowledge as an alternative to Western mainstream scientific

Extreme views - Millom walk

methodologies.

“Sand Talk”, Tyson Yunkapora Dr. Tyson Yunkaporta is a researcher, arts critic, poet and traditional woodcarver. In this book, which looks at global systems from an Indigenous perspective, we humans are no more important than rocks.

Back To The Land Reader

This reading list is for students on the summer course John Thackara runs together with Konstfack, in Sweden. These texts span how to be, as well as what to do, in an urban-rural context. thackara.com

Some examples of UK nature connection experiences that designers can try for themselves:

Deep Time Walk - explore Earth history and geological time deeptimewalk.org

Morethanweeds - change your perception of urban plants morethanweeds.co.uk

Nature Connection Retreat - make an inner journey in the great outdoors sharphamtrust.org

Learning Farms - connect with 120 School Farms in the UK farmgarden.org.uk

Connect to Nature - various natured-based airbnb experiences airbnb.com

Vision Quest - soulmaking in nature wildrites.uk

Soil Care Network – “Rediscovering Soils” workshops soilcarenetwork.com

Soil Voices - collect stories and memories about soil soilvoices.org

Quench - Nature Connection in Urban Environments lancaster.ac.uk

Wild Minds Collective - nature connection retreats, vision quests, online journeys dandelion.earth

Circle of Life Rediscovery - work with experienced pioneers in nature-based practice circleofliferediscovery.com

Embercombe - reconnect to your wild self embercombe.org

Schumacher College Short Courses –progressive college offering ecological studies in the classroom, the gardens, the kitchen campus.dartington.org

Centre for Alternative Technology Short Courses - day and short residential courses covering a range of sustainability issues cat.org.uk

Rewilding Academy – training and courses in rewilding rewilding.academy

Pishwanton Wood Project - Life Science Trust inspired by Goethe garvaldedinburgh.org.uk

Work That Reconnects Spiral - hear sounds of the Earth crying whiteawake.org

Walking The Forest – project exploring the connection between women, activism and trees walkingforest.co.uk

8 Words for Barrowmittens

can find out more and learn from our other inaugural Design for Planet Fellows

to the Design for Planet Fellows Exchange

You

by listening

podcast:

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-mission/design-for-planet-fellows/ This

Credits

Design for Planet Fellows

Tayo Adebowale

Carole Collet

Sarah Drinkwater

Finn Harries

Nat Hunter

Torange Khonsari

John Thackara

Josie Warden

Design Council Project Team

Cat Drew

Bernard Hay

Lucy Wildsmith

Podcast

Alisha Morenike Fisher

Lucia Scazzocchio

Graphic visualisations

Valentina D-Efilippo

Fellowship Graphic Identity

Gabi de Rosa

Graphic Design of ‘Three Perspectives’

Maryam Atta,

Thank you to The National Lottery Community Fund for funding this project, and to the RSA and Careful Infrastructures for their support of the programme.

R-Urban_Poplar

R-Urban_Poplar

R-Urban_Poplar

R-Urban_Poplar

10.EXTREME VIEWS - MILLOM - with rose tinted glasses. Photo Maddi Nicholson

10.EXTREME VIEWS - MILLOM - with rose tinted glasses. Photo Maddi Nicholson