5 minute read

Editor’s introduction

It’s been a great pleasure to be the guest editor of this publication. Many of the texts you will read are transcribed from presentations at the Design Council’s Design for Planet Festival 2022, hosted by Northumbria University and featuring a rich breadth of voices. It would have been an impossible task to collate all the talks and ideas from the Festival, so instead I have extracted select edits and moments, published here alongside a host of newly commissioned writing from thinkers and doers of various disciplines - and I want to thank all those commissioned writers for responding with passion, wit, and creativity on a very short deadline.

Also included is writing from the hosts of the 2023 edition of the Festival, the University of East Anglia in Norwich [UEA].

Advertisement

I want to extend thanks to all contributors from the university, but especially Alexander Bratt who is not a writer here but grabbed the opportunity to engage his various colleagues in support of this publication, leading to some valuable insights and foreshadowing for the next Festival.

There are loose themes and strands flowing between the following pages, though there is no central, singular editorial answer. Instead, this publication celebrates plurality and interconnectedness between disciplines and people - whether intentional or accidental.

Connection and interaction is central to design, which is fundamentally a process of creating new relationships - to each other, to systems, or indeed to the planet.

The richer and more varied those connections and relationships are, the stronger any designed outcome will be. Plurality is integral to design.

The solutions to climate breakdown also require a plurality of ideas - there will not and cannot be a single solution. It will take a million designed responses: from the largest systems of energy production to the smallest retrofit; from grand physical propositions to imagining new collective and individual ways of being; and designing new ways of looking and relating to others with empathy and awareness - whether those others are human or nonhuman.

Coinciding with the Design for Planet 2023 Festival, the Sainsbury Centre at the UEA - housed in Sir Norman Foster’s distinctive architecture - hosts an exhibition curated by newly appointed Curator of Art and Climate Change, John Kenneth Paranada. In this publication, Paranada previews his exhibition Sediment Spirit and describes anthropogenic climate change as “something intimate, immediate, interconnected, hyperlinked, and altogether quite abstract to grasp.” His role is the first of its kind in any UK museum and he will lead research and deliver a range of activities that promote sustainability and engage with the climate crisis - precisely the kind of collaborative interdisciplinary connections needed.

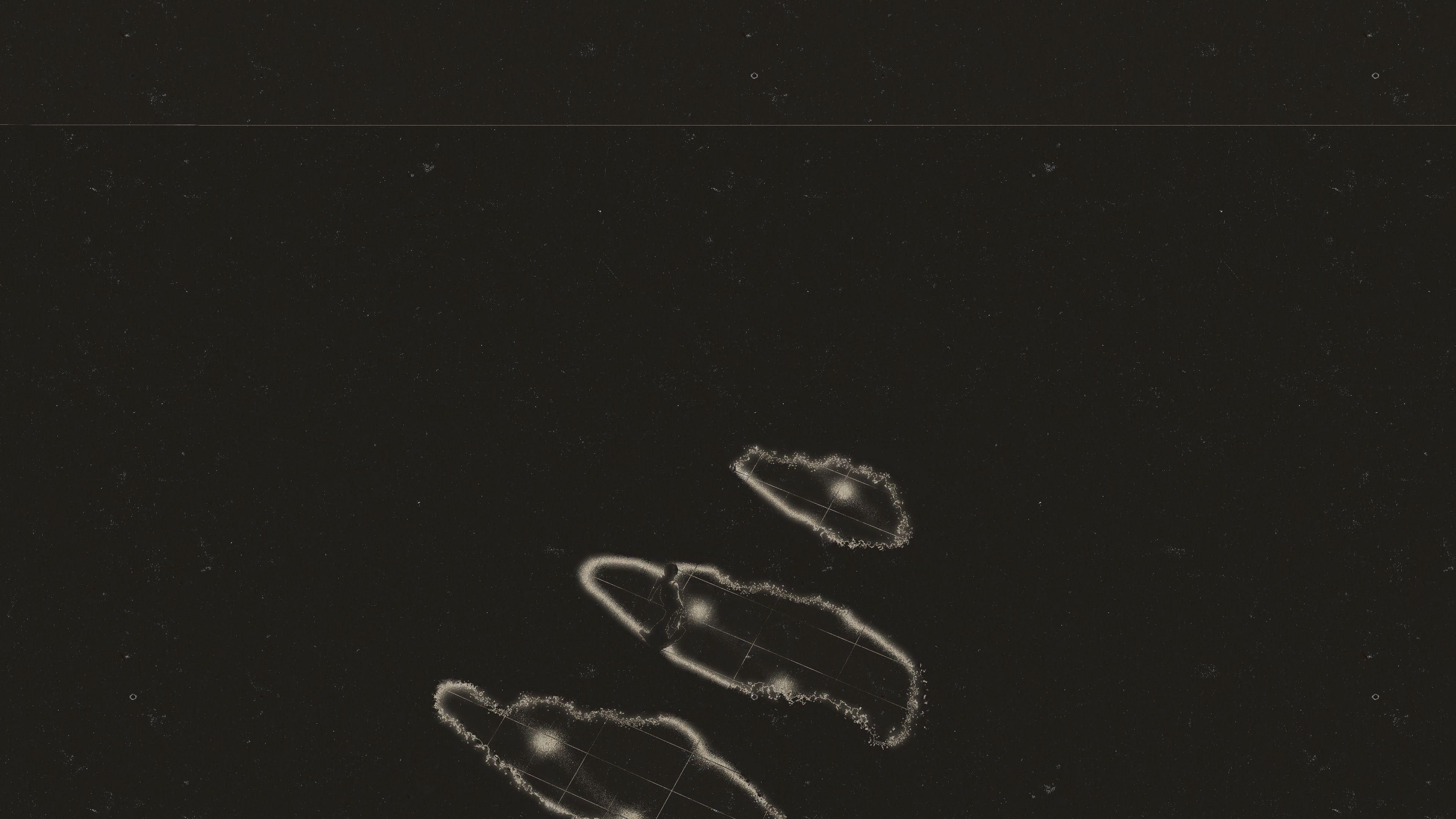

In editing this, I was keen to push at the boundaries of what design is and how it permeates other disciplines, especially the creative arts. I was so pleased that seven visual artists have contributed work spread throughout the publication, images which should not only be read as beautiful pauses between text, but as connective tissue between ideas and propositions you will read, and in their own right as creative tools to help us see and think differently. As Steve Waters, dramatist and UEA Professor of Scriptwriting, writes in his text “the very nature of our stories may need to change” and the creative sector will be at the forefront of those stories.

To this point, I am especially glad to include three short pieces from writing students at the UEA. Amongst all its academic and research pedigree the UEA is perhaps most well known as a centre of creative writing. It was at the UEA that WG Sebald worked for three decades, a writer whose 1995 book Rings of Saturn deeply studied the decaying, reforming, and resonant Suffolk coastline, connecting it to a plurality of histories, situations, and nature beyond. It is a study of place, but also of existential relationships, and Sebald writes:

“Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers. From the earliest times, human civilisation has been no more than a strange luminescence growing more intense by the hour, of which no one can say when it will begin to wane and when it will fade.”

The machines we devise from here on must all be designed with relationship to the planet hardwired, or the fading of civilisation Sebald saw within the saturated coast will certainly come sooner rather than later. Rings of Saturn was, however, perhaps a story for a different generation and different thinking - an age of reflection, mourning, and recognising. Stories and machines we design going forward may not need to be created in fear, but borne from progressive, collaborative, and creative optimism - and indeed utopian thinking. In his text for this publication, Professor of Landscape at University College London, Tim Waterman, states that “utopias are tools for better futures.” Everybody included within these pages is invested in that better future, and each is designing new utopian relationships at various scales.

I want to thank all at the Design Council, especially Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino for inviting me to guest edit with such creative freedom and Niamh Crawford for always being an email away to help propel the project forwards. Finally, huge thanks to Niall ÓConnor who has designed the following beautiful pages with creative play and an admirable sense of calm.

Many of the following texts are drawn from the 2022 Design for Planet Festival presentations. I encourage you to visit the Design Council’s YouTube channel where you can experience the talks at your leisure and to look out for updates on the 2023 UEA-hosted edition to continue the conversations and create new relationships

- Will Jennings Writer & Editor