16 minute read

Design Identities: Celebrating Black College of Design Alumni

Cover Art and Alumni Portraits by Sophia Chunn

“We believe that great design has the capacity to improve

the lives of people,” says Edwin Harris [BEDA ‘04, B.Arch ‘05] in an interview with current design student Jasmyn Byrd. “How can we create spaces and designs that are going to improve the lives of anyone who experiences them?”

That sentiment resonated across five separate interviews, all a part of the College of Design’s Design Identities virtual exhibition. The exhibition explored the careers and work of Black designers from each of the college’s disciplines, and what the designers’ personal experiences brought to their work. Through video interviews with current students, alumni shared what led them to find the College of Design and pursue their current career paths.

For many, their first exposure to the college was the School of Architecture. “I walked into this university thinking I would be an architect, and then I got in my first semester studio and fell in love with fabric manipulation,” says Charles Harbison [BAD ‘04}.

“My grandfather suggested I become an architect – all I knew is that you get to create things, you get to draw, and so from that point on, I pushed towards architecture,” added Edwin Harris. Thrilled to be accepted to the College of Design, Breeze Outlaw [BEDA ‘12, B.Arch ‘14, MLA ‘16] didn’t feel that the philosophies in architecture lined up with zir own philosophies, which led zir to pursue the Master of Landscape Architecture. “I was able to really start to challenge myself as a student. How can I actually see myself in the curriculum and in design?” zie adds. At that time, Breeze still didn’t see zirself. Sharing this common thread of not recognizing themselves in the design

environment, these alumni have forged different paths to success and continue fighting for change in their respective professions.

Renee Seward [MGD ‘07] offers some words of encouragement to current and future design students: “Our thoughts and our minds and the backgrounds that we come from are necessary to help address the problems that are ahead of us in this world,” she says. “I want [students] to go out there, and be comfortable in the room that they’re in, and to speak the knowledge that they know – you deserve a seat, you got a seat, take the seat and change the world,” she encourages.

14 | NC State University College of Design | design.ncsu.edu

— RENEE SEWARD

Breeze Outlaw is a landscape designer

interested in addressing the perceptual and physical interpretations of equitable and just access to public spaces. As the first person in zir family to go to college, zie began zir studies at UNC-Greensboro before transferring into the School of Architecture at NC State.

Thrilled to be accepted to the College of Design, zie didn’t feel that the philosophies in architecture lined up with zir own philosophies, which led zir to pursue the Master of Landscape Architecture. Working with faculty like Kofi Boone inspired zir.

“I was absorbing everything that Kofi [Boone] was teaching, and that led to my final project to look at neighborhoods and invest in the infrastructure that is needed to preserve cultural integrity. And that’s the journey I’m on right now – trying to figure that out and refining it as I get more into the profession,” zie says.

In zir work, zie explores frameworks of resilient sociocultural equity through futurism, cultural expressions, and natural systems. “One of the things I’m trying to do within my own practice is to be aware of the equity factor within the work that I do, making sure that I’m being conscious of the impact that the work that I’m doing has on the people that will be using the space or what that space perpetuates in the sense of either equity versus harm,” zie adds. As a junior designer at Sasaki, Outlaw started to feel as if zie wasn’t contributing zir fullest. “At what point am I going to learn the skillsets and leadership skills I need to be the best landscape architect I can be?” zie says. “From there, I started to speak up for myself and built on that momentum of needing to advocate for myself.”

Zir personal journey has involved engagement with the community in any project zie’s worked on – being aware of not just traditional demographics of the community, but demographics related to food insecurity and exposure to violence. “The process I’m doing with engagement evolves all the time – you learn new things and try to be sensitive when you engage with people,” zie adds.

Outlaw reflects on one of zir favorite projects – the Frederick Douglass Memorial Plaza in Roxbury, Massachusetts. “This was the first project where I felt the most valid in the sense of bringing my identity into a design,” zie says.

Zie started working with the community to foster a space for healing and think about what beauty meant to them in their space. “We wanted to find a way to convey this reclaiming of space, of developing a safe space,” zie says. The design incorporates African textures and patterns, and the planting palettes used were influenced by African American gardens – using bold colors, bold textures and asymmetrical designs. “We’re trying to invoke memory and a sense of smell, and be a place for people to celebrate, and reflect, but also a space for existing,” zie adds.

“One thing that I’ve been doing is being conscious of myself – unlearning or being very critical of the design thinking I’ve been taught. It takes a lot of work – you have to be really understanding of the power dynamics within these spaces, public or private,” Outlaw says.

Above Left: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial Plaza. Right: Renderings of the WE app for the Montreal Gay Village in Montreal, Canada. Developed by Sasaki.

design.ncsu.edu | NC State University College of Design | 15

“As a Black woman, my identity of

being Black sometimes supersedes that of being a woman, and all of this came out in this poster I was working on for AIGA,” said Renee Seward, director of the Communication Design Program at the University of Cincinnati for the past fourteen years. She was asked to create a poster encouraging women to vote, but with the events happening in June 2020, that evolved the way she tackled the work. “I was happy that that opportunity came my way, and that I could make what I want and say what I want, but I was slightly nervous in how it would be received,” she adds.

Including her voice paid off - she recently was named a winner in the Graphic Design USA Design competition for the poster she developed for the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) to promote voting. Reaching this point in her career has been a long road, but Renee has never been shy about speaking her own truth.

“I think there are lots of good discussions and when you have lots of different voices, you can hear everyone’s perspective. I think the love in my research is dealing with people who can’t read and seeing the world from their perspective and how they solve problems. So, difference is good,” she adds.

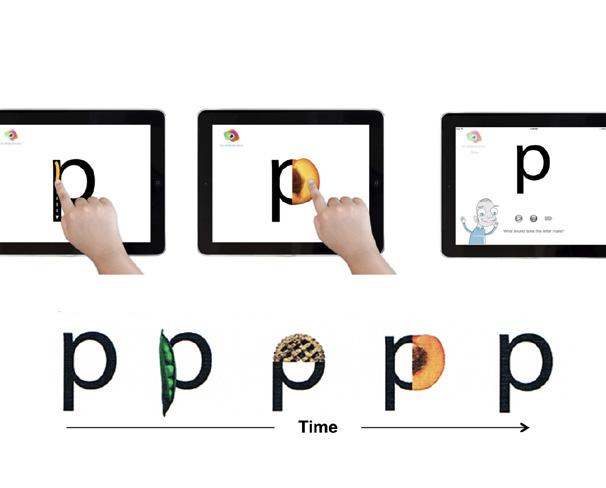

Through her company, See Words Reading®, she does research that focuses on developing digital and physical tools that seek to address our society’s literacy problem. “When I started on this project, it was my thesis at NC State. iPads weren’t even around. I was just hypothesizing on how touchscreen technology would impact education,” she says.

She started by going to private schools and seeing how teachers there helped students who were struggling to read. She quickly realized that children in public schools faced the same issues, but without the benefits of small classrooms and individualized attention. So, she brainstormed how to use technology to make an impact in larger school environments.

Becoming a teacher gave her the time and space to ask the questions that she wanted to ask: What can design do? How can design influence and help her community?

When she was early in her career, she felt that her work wasn’t reflecting her as its target audience. “That bothered me,” she says. “I would be asked to design an angel, and I would make a Black angel. And the client would have issues until it became a white, blonde angel. It seemed like whenever you brought in a person of color, that the message was talking about diversity or it’s talking about people of color, and that wasn’t the target audience. So I started stepping away from those projects.” Her past experiences led her to the advice she gives to new Black students entering the profession. “Our thoughts and our minds and the backgrounds that we come from are necessary to help address the problems that are ahead of us in this world,” she says. “I want [students] to go out there, and be comfortable in the room that they’re in, and to speak the knowledge that they know – you deserve a seat, you got a seat, take the seat and change the world,”

Top: Award-winning AIGA poster encouraging women to vote. Middle: Early education reading font. Bottom: Example of See Words Reading®

16 | NC State University College of Design | design.ncsu.edu

my first semester studio and fell in love with fabric manipulation,” says Charles Harbison, Art + Design graduate and founder and creative director of HARBISON. From there, he fell in love with fiber arts, tapestry, weaving, and textiles from around the world, and decided to switch to Art + Design and Textiles with the intent of pursuing fashion design in New York.

After receiving a bachelors degree from NC State, Harbison took a year to study textiles in Central Asia before moving on to Parsons School of Design. During his time there, he interned at Jack Spade before landing his first job at Michael Kors. From there, he worked at Luca Luca and Billy Reid, before finally launching his own collection in New York, HARBISON. Since then, the brand has pivoted to be a studio in LA, where he has been able to dress the likes of Beyoncé, Solange, and Ava Duvernay.

As Harbison continued to grow and shape his own design aesthetic, he reflects on how it all stemmed back to his experience growing up with his mother in a small mill town in NC. “I come from blue collar people, and I would see my mom transform on the weekends from a mill worker to this elegant, confident, beautiful woman. And it had less to do with what she looked like and more to do with being able to tell that she felt great.”

Realizing that connection to his own personal history was a journey that he continues to this day, but was also one that he felt gave him a huge advantage starting out in New York. “I was a country boy in this urban environment – honor your background in your work, even if it may feel difficult because in the end, it is your point of differentiation, and a reason for people to look back at you and you particularly,” he adds.

Harbison continues to put his identity at the forefront of his work, to help increase the representation of Black people – not just in fashion, but in entrepreneurship, ownership, talent, and decisionmaking. “We’re getting there – but we have a way to go. The goal now is to make sure that we are not depending on the next generation’s response to representation to invoke more change, but that we’re also pushing as hard as we can to take the

“The goal is to stop configuring a space where you’re looking to be represented but configuring a space where you’re inherently represented.” — CHARLES HARBISON

representation and center that ownership so that you’re not always configuring a space where you’re looking to be represented but you’re configuring a space where you’re

Left to right: Images from Harbison’s collection, HARBISON. Designed with a focus on construction, balance, and the modernist code, each HARBISON collection serves the customer who sees beauty through the lens of contradiction, modernity, and luxury. More info at harbison.studio. Photos by William Hereford.

design.ncsu.edu | NC State University College of Design | 17

“I was initially drawn to car design and shoe design - I didn’t even know that industrial design was a thing,” says Edwin

Harris, co-founder and design principal at EVOKE Studio and professor of the practice at the College of Design. “Then my grandfather suggested I become an architect – at that point, I couldn’t name one architect. I had never met one, I didn’t know anything but that architects design buildings. All I knew is that you get to create things, you get to draw, and so from that point on, I pushed towards architecture.”

Harris’ grandfather was a pivotal figure in his career trajectory towards becoming the architect he is today. After introducing the idea of architecture as a career path, his grandfather continued to help him achieve his dreams. Harris applied to the College of Design three times – twice unsuccessfully, before finally being accepted.

“My grandfather called up Phil Freelon and told him that my grandson wants to become an architect,” Harris remembers. “So, Phil Freelon met with me on a Friday in his office and he said ‘we’re going to get you into the school of design.’” He maintained a positive relationship with Freelon, even working at the Freelon Group for nine years before founding EVOKE.

While at the Freelon Group and Perkins+Will, his visioning for projects like Emancipation Park garnered him recognition as an emerging designer for the global firm. Emancipation Park embodies much of what would be the founding principles for EVOKE.

Former slave Reverend Jack Yates led community members of Antioch Baptist and Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church in Houston, Texas to purchase land for Juneteenth celebrations in 1872. Under racial segregation, the park was the only one in the city for Black people to use. The park underwent $33 million in renovations in 2017, led by Perkins+Will with Freelon heading the design team.

“We believe that great design has the capacity to improve the lives of people. So, we’re really ambitious about design and its capabilities – every project that we take on, from the smallest to the largest – how can we create spaces and designs that are going to improve the lives of anyone who experiences them,” say Harris.

He feels that his own personal ambition is driven by the desire to build upon the sacrifices of the previous generation.

“As a Black person in America, our ancestors fought so hard for freedoms and made sacrifices for freedoms that they never achieved and they did it for us,” he adds. “I’m trying to strive for greatness, not just for myself but for the people who come before me. I want to be able to tell them, ‘look, [your sacrifice] wasn’t all for nothing.”

Below Left: 5 Points Plaza in Charlotte, NC. Designed in collaboration wtih James Stacey Utley. Middle: Rogallo Museum of Low-Speed Flight, Nags Head, NC. Right: Emancipation Park, Houston, TX.

18 | NC State University College of Design | design.ncsu.edu

“The people who have experienced the most amount of exclusion are the most equipped to embrace empowering people and efforts that encourage inclusion,” says Tim Allen,

reflecting on his own experiences as member of a marginalized group of people in design.

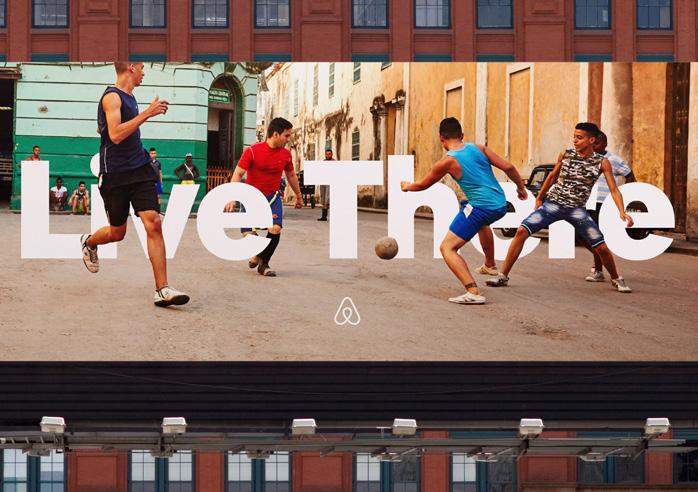

Now, as the leader of the global product design team at Airbnb, Allen is focused on what it means to design for everyone. In his role, he’s tasked with empowering his team of creatives to produce effective and meaningful work.

Allen describes his journey into design as a “reverse of an onion peel” – starting out by airbrushing and painting in high school. By the time he was a sophomore, he had his own small business working on boats, cars and signage for local businesses.

Unaware of the existence of design schools at that time, Allen sought out a future as businessman rather than a designer.

“I didn’t know what a portfolio was. To me, that book full of work that I had was just a part of my business,” he adds. “After hearing about the College of Design, that book became my portfolio. NC State was the only school I applied to.” According to Allen, developing a sense of awareness plays an integral role in his love for digital product design and user experience. During his time at the college, a curriculum focused on interactive design did not yet exist – leaving Allen to build his own realm of study combining psychology, industrial design and art.

“There are universal human truths,” he notes. “We all want to belong. We all want to connect. We all want to be creative. While you elevate those universal truths, there’s the nuance of understanding what makes us all unique. Inclusive design is really about discovering what belonging means to each individual.”

Allen credits faculty members such as Pat FitzGerald and Chandra Cox with making social responsibility in design a priority for himself as well as other students.

Thinking about the next generation of Black designers, Allen feels that finding a place which aligns with your values is critical, and encourages students to take culture seriously when looking for a welcoming community.

“Your unique view of the world is sorely needed in an extremely homogenous industry. It’s not going to be easy to develop your voice, but it’s worth it,” he says.

“There are numerous companies, brands and agencies that are craving new approaches and new ideas. Your contributions, your impact, can be great.”

Below Left: Typeface design for Airbnb. Middle: Brand and product design for Nike Digital Sport from Allen’s tenure at R/GA. Right: Brand design for Airbnb.

design.ncsu.edu | NC State University College of Design | 19