12 minute read

The Levin Legacy

OUR COMMUNITY

ON THE COVER

Advertisement

Carl Levin’s new memoir chronicles his 36-year Senate career. The Legacy Levin JACK LESSENBERRY CONTRIBUTING WRITER

COURTESY OF WSU PRESS

City Council days. Detroit, circa 1970.

Carl Levin, the longest-serving U.S. senator in Michigan’s history, admits he had to be pushed into writing his memoir, Getting to the Heart of the Matter: My 36 Years in the Senate, recently released by Wayne State University Press.

And we should be grateful to his wife, Barbara, and his longtime aide Linda Gustitus for doing just that. Political memoirs are often little more than self-satisfying ego trips; I confess I fell asleep trying to make it through Bill Clinton’s autobiography, and while better written, Barack Obama’s history of his presidential years may threaten to be longer than the Talmud when finally finished.

Not this book. This is the story, in little more than 300 pages, of a good and decent man who never lost an election, and about whom, after more than half a century in public life, there has never been the slightest whiff of personal or professional scandal.

You wouldn’t know from this book that he became the only statewide candidate in Michigan history to get 3 million votes. In fact, except for his first campaign, in which he performed the difficult feat of knocking off a powerful incumbent senator (Robert Griffin) and his second, when he managed to survive the Reagan landslide, Levin barely mentions his elections; and the last two, not at all.

Nor is this a personal tell-all; what details of his early life we get leave us wanting more. I had no idea that Levin was once a motorcycle fiend who broke his kneecap and otherwise smashed up his right leg crashing into a stone wall in Florence, Italy, or that he worked the line in three auto plants in Detroit and Highland Park.

Many readers also may be intrigued to know that his paternal grandparents, Morris and Gittelle Levinson,

COURTESY OF WSU PRESS

President Obama and Sen. Levin at the White House, Oct. 28, 2009.

Q & A with Sen. Levin

JACK LESSENBERRY

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

I talked with Sen. Levin at length when his book was published. Here are highlights of our conversation.

Did being Jewish influence how you saw your role?

It surely did. I think the values in Judaism are important — the values of being charitable, of thinking of others, the important Jewish values which I learned early in life: To take care of the poor, of each other — to watch out for each other and treat others the way we want to be treated. And thinking about the legacy of generations of antisemitism has made me very sensitive to others who are victims of prejudice and discrimination.

There’s long been a belief that Congress is broken, but people now appear to believe that more than ever.

I agree. There is increased divisiveness — it has gotten worse over the last decade. There are some points where it is totally dysfunctional. This started, I think, with the Tea Party and their leader [former Speaker of the House] Newt Gingrich, and their idea that you should not compromise. We have to understand that unless you are willing to compromise, you aren’t going to reach your goals.

When I was on the City Council, I learned to listen to the other guy, and that he has a point of view. You don’t have to agree with it, but you darned well better understand it. That’s how you find a way to achieve the common good.

Now it is true that if one party has a majority in both houses and holds the presidency, you can get away with a lot of ideological rigidi-

continued on page 14

— SEN. CARL LEVIN

Q&A from page 13

ty, but if government is split, you have no choice but to work together. Sometimes in a family, you learn that, too.

You know, Sandy [his older brother, former U.S. Rep. Sander Levin] is my role model. Talk about bringing people together! He did that as leader of the Democrats in the Michigan Senate.

By the way, he is also the one who taught me how to play squash — starting when I was a freshman and he was a senior at Harvard Law School. We calculated a while ago that we’d played something like 15,000 games together over the years.

How can we fix things?

No. 1, elect a president who wants to work together — and we’ve done that. Trump was the most divisive president in our history. He appealed to racial biases, ethnic biases and set different sections of the country against each other.

Do you think President Biden is the right person for the right time?

I sure do. I think his background is right. Biden is known for bringing people together to look at problems. You need someone who is not anti-government. We worked together in the Senate for many years. I saw the way he worked with people. He was a big part of always getting things done.

But we also need leadership in Congress who are willing to work together and like each other even if they disagree. People who can argue but then have a drink together and laugh together. They have to know how to get along.

How did you feel when you saw the riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6?

I was disgusted, obviously. To witness the central process of our democracy being subject to an attack — a betrayal of so much in this country and what we stand for. But when I see the voters in this country defeating a divider and electing a unifier, it makes me feel confident that nothing will tear down this democracy.

I think we withstood a storm with Trump. That democracy came out stronger than ever. What happened [Jan. 6] was a real lesson for our country, and I think we came out stronger.

Finally, why did you write this book?

I wanted to share with my family and anyone else who might be interested what I had learned in politics and share it with anyone who might possibly find it an incentive to go into public service.

Public service is an honorable profession, whether elected or appointed or volunteer. Young people need to realize how important it is.

OUR COMMUNITY

LEGACY from page 12

were the first Jews to arrive in Birmingham in the 1890s, where they started a little store at Maple and Woodward that eventually became four stores.

While I found all that fascinating, this is really a book about how government, principally the Senate, works, and what needs to be done to make it work better. Levin does provide a concise and mostly interesting history of the major issues of our time, especially the ones in which he played a role, from the armed services, his best-known area of expertise, to the Clinton impeachment to the auto industry and financial crises of the Great Recession.

There is a weak point or two; he discussed the emotionally wrenching right-to-die controversy involving a vegetative-state patient, Terri Schiavo, without mentioning that her feeding tube was eventually removed. Also, if you aren’t an accountant, your eyes may glaze over at the level of detail provided when he recounts the financial abuses his Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations uncovered.

However, the U.S. Senate is divided into show horses and work horses, and this is a good reminder of how hard a good U.S. senator must work to do his job the way it is supposed to be done.

MAN OF THE SENATE

Nobody ever accused Carl Levin of being a slacker. The fundamental message of this book is one about governing. “If you don’t come to elected office willing to compromise, you don’t come wanting to govern,” Levin says in discussing the role of an elected official.

He also has a view on the nature of his job many who are in Congress — or, for that matter, any elected position — ought to hear. “Being an effective representative, I’ve concluded, doesn’t necessarily mean voting in the way the majority of one’s constituents think best.” Instead, he thought it was his job to “seriously study, without arrogance or certainly” any issue, “being open to and respecting different views,” and then “do what I believed was in the best interests of my constituents in the long run.”

That at times, meant unpopular votes, from opposing our war against Iraq in 2002 to voting against the Reagan tax cuts in 1981, a vote that might have cost him reelection, had his opponent, astronaut Jack Lousma, not been filmed praising Toyota and telling Japanese auto executives how happy he was that his son drove one.

Levin was, and is, thoroughly a man of the Senate, including its rules and traditions. Some reformers may be dismayed to learn, for example, that he stoutly defends the practice of “earmarking” funds for special local projects, something opponents call “pork-barrel” spending. Levin believes that while there have indeed been some abuses, earmarks are “a legitimate part of the legislative process.”

While all will not agree, he makes a compelling case for his position. He is also adamantly opposed to abolishing the much-maligned filibuster. True, there are times when it has been used to obstruct progress, but Levin also thinks it is a huge mistake for either party to resort to the so-called “nuclear option,” one in which the Senate overrules the rule that you need 60 votes to end debate.

Instead, he recommends that instead of just allowing opponents to stop debate by threatening to filibuster, the majority should call their bluff and force them to do it; in most cases, he thinks those threatening to stage

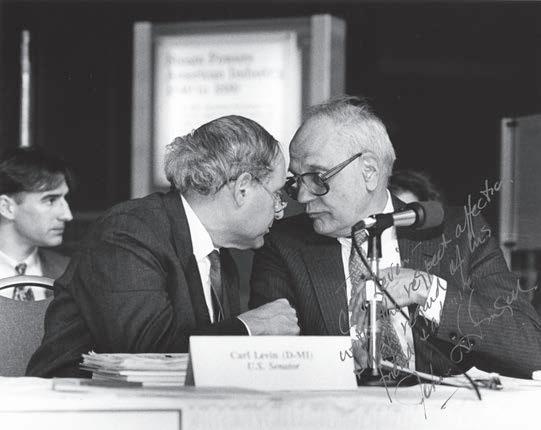

HS19604, CARL M. LEVIN PAPERS, BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

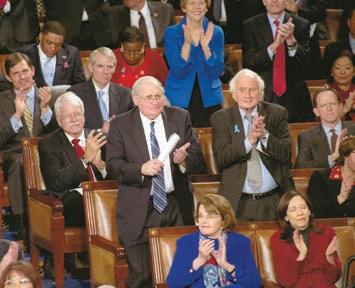

PHOTO BY JAY MALLIN/THE WASHINGTON

POST VIA GETTY IMAGES TOP ROW: Conferring with Michigan

congressman John Dingell before testifying together. Signing ceremony with President George W. Bush on the FY 2004 National Defense Authorization Act, Nov. 24, 2003. Left to right: Sen. John Warner, Sen. Levin, Rep. Tom Davis, Sen. Susan Collins, Rep. Duncan Hunter.

BOTTOM ROW: Carl and Sandy Levin at one

of dozens of State of the Union addresses where they always sat together. Going after Chinese counterfeit auto parts before the U.S.-China Economic Security Review Commission, June 7, 2006.

an endless debate would soon back down.

DETROIT ROOTS

But though he is a man of the Senate, Carl Levin is, even more so, a man whose roots are firmly in Detroit.

The one incident he cites at the very beginning of this book, something that shaped his career, happened when he was Detroit City Council president in 1975 and incompetent administrators at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development were refusing to tear down blighted homes they owned.

He led the Council to defy HUD and tear down the homes anyway, and dared HUD to sue, saying, “Do you think even one out of 12 jurors would vote to convict?”

They didn’t sue. Levin said HUD’s incompetence “convinced me that our elected members of Congress were not taking responsibility for overseeing the programs they had voted to establish.”

That helped lead him to the Senate, where he rigorously tried for a third of a century to hold those responsible who ran, and sometimes mismanaged, the country he loved.

The voters clearly felt he did something right. They reelected him the most times in Michigan — and longer than all but 19 senators in the history of the country; one of whom beat him by a mere 13 days is Joe Biden. (An interesting bit of trivia: Levin is also the longest-serving Jewish senator in U.S. history.)

A few years ago, not long after Levin announced he would not be a candidate for a seventh term in 2014, I asked him … why not?

True, he was going to be 80 that year, but many senators serve well past that — and Levin seemed more like a 60-year-old. He was strong, intellectually vigorous and at the top of his game as chair of the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee. Throughout Michigan, he was widely respected, even loved.

Republicans had barely fielded even token opposition in his last two races; winning reelection one more time would have been a virtual certainty. So why not run again? Levin smiled. Yes, he said, he did feel great, physically and mentally — “Now, yes. But I don’t know how I will feel at 86 [the year his next term would have ended]. Besides,” he added, “I want to spend more time with Barbara and get back to Michigan.

That was all true — and reflective of who Levin is. Few longtime senators or congressmen return to their home states after their political careers; they stay in Washington or retire to the Sunbelt.

Not Levin; he and Barbara, who will celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary this year, came back to where his political career began, Detroit, where he served two terms on City Council half a century ago, before his first campaign for the Senate in 1978.

Leaving the Senate hasn’t meant retirement; he joined the Honigman law firm in Detroit and helped establish the Levin Center at Wayne State University Law School, which is designed to focus on, he said, “the essential role that fact-based bipartisan legislative oversight plays in our nation’s constitutional system of government with its emphasis on checks and balances,” which was, in fact, perhaps the main focus of Carl Levin’s career in the Senate.

His thought that nobody can be too sure of their health after 80 turned out, sadly, to be all too true; in 2017, Levin, a former cigar smoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Fortunately, he was able to fight it; today at age 86, although his voice is raspy and no longer as powerful, he says his health is “stable.”

DETAILS Getting to the Heart of the Matter: My 36 Years in the Senate. By Carl Levin 338 pages; $29.99. Wayne State University Press, 2021