7 minute read

Preserving the Legacy of Albert Kahn

MICHAEL G. SMITH

Advertisement

14 | JANUARY 28 • 2021 MICHAEL G. SMITH

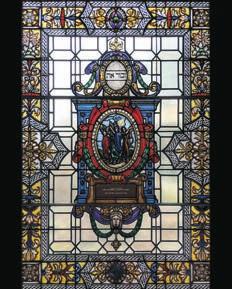

BURTON HISTORICAL COLLECTION, DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY TOP: Temple Beth El, Woodword and

Elliot, 1903 (later the Bonstelle Theatre).

LEFT: Stained glass window from Kahn’s

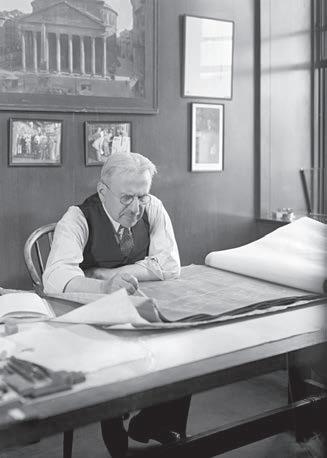

Temple Beth El, now on display at Temple Beth El in Bloomfield Township. A display from the Kahn Legacy Foundation quoting the architect, “Nine-tenths of my success has come because I listened to what people said they wanted and gave it to them.” A photo of young Albert Kahn, in foreground, at the Mason & Rice firm, 1888.

JEWSIN THED

ON THE COVER

Dedicated historical foundation to honor life’s work of Detroit’s master architect.

SHARI S. COHEN CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Many Detroiters have visited the Fisher Building, 1900 and 1940. His firm was the official consulting archiBonstelle Theatre or the University of Michigan’s tect for the U.S.S.R.’s Five-Year Plan and designed 500 facHill Auditorium without realizing that they were tories there from 1929-1931. In addition, Kahn designed designed by Albert Kahn. many American military facilities for World Wars I and II,

“He hasn’t gotten his place among famous Detroiters — as well as factories that produced war materiel. his story doesn’t go everywhere although his work does,” says Heidi Pfannes, senior assoALBERT KAHN ASSOCIATES ciate and director of business development at Albert Kahn Associates Inc. and president of the new Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation board. As an immigrant from a poor German Jewish family, Kahn’s formal education ended at the seventh grade. However, he was mentored by several Detroit architects, studied extensively on his own, and demonstrated extraordinary talent, focus and determination as an architect at an early age. Kahn achieved great success at a time when antisemitism Kahn at his desk, 1940. was widespread in the U.S. and Detroit. During the 1920s and ’30s, Detroit newspaper ads for apartment rentals could specify “No Jews or dogs.” Kahn designed at least two private clubs early in the 20th century — the Detroit Athletic Club and Detroit Golf Club — that did not admit Jewish members at the time they were built.

Despite all these obstacles, Kahn’s body of work is astonishing in its breadth of design styles, construction engineering innovations and the scope and volume of his projects — including factories, office buildings, synagogues, auditoriums and a hospital among many others.

The firm he established in 1895, now known as Albert Kahn Associates Inc., designed 2,000 factories between

LEGACY CELEBRATED

Last year, a group of local historians, architects, archivists and other interested volunteers established the Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation to “celebrate and preserve the legacy of Albert Kahn, often described as the foremost American industrial architect of the 20th century.” One of the motivating factors for the foundation’s creation was the 125th anniversary of Albert Kahn Associates Inc. last year. “We were getting so many requests for the Albert Kahn archives,” Pfannes explains. “So many people are passionate about Albert Kahn. We didn’t want it to be a company foundation. We need to be supported by the community.” About the same time, several Detroiters interested in history and architecture were talking about recognition for Kahn’s achievements. Kahn Legacy board member Levi Smith of Troy says that over the years he had visited The Henry Ford museum and Greenfield Village many times and noticed that there was no Jewish representation there. This oversight was particularly striking since Kahn designed the Ford plant, where the Model T was built, and the Ford River Rouge Complex among many other Fordrelated projects. “I started talking to people, and we put together a group,” he said, with an initial goal of obtaining recognition for Kahn at The Henry Ford. Smith, besides being a Kahn Legacy Foundation board member, also chairs its Museum and Exhibits Committee. Detroit’s rebirth and the rehabilitation of some of Kahn’s Detroit buildings also made this particularly timely. Eventually, the individuals interested in preserving Kahn’s legacy coalesced and established a nonprofit corporation — the Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation — last year. Their

JEWSIN THED

ON THE COVER

Ford Motor Company Highland Park Assembly Plant. Built in 1910, it was nicknamed the “Crystal Palace.”

continued from page 15

goal is to collect, preserve and display the public materials related to his life so that “researchers, students, historians and the general public will know and appreciate how his designs and ideas changed industrial America and helped make Detroit the manufacturing capital of the United States during the first half of the 20th century.”

POP-UP EXHIBIT

The Legacy Foundation wants to provide a space for archives preservation and plans to create traveling exhibits and offer educational programs. Their first effort is a “pop-up” exhibit introducing Albert Kahn and his achievements, designed by Eric Keller, a volunteer. (Some images from the pop-up exhibit are included with this article.)

Volunteer board members are considering possible exhibition locations — museums or libraries in Detroit and Ann Arbor as well as Kahn-designed buildings. However, they may wait until the COVID pandemic restrictions are loosened and permit greater foot traffic in public buildings.

Long-term, the board is considering the feasibility of creating an Albert Kahn museum. “Ideally, we want something permanent,” Pfannes says, “but there are pop-ups in the meanwhile. We need to raise money for a feasibility study for a museum. We’re working on partnering with the Fisher Building, Argonaut Building and Urban League (which has its headquarters in Kahn’s family home) — all designed by Kahn.”

“He is part of the Detroit community, the Jewish community. We have so much history, but people aren’t aware of it,” says Barbara Cohn, Kahn Legacy Foundation board member and co-author of Detroit Public Library — An American Classic. The Foundation is hoping to attract paying members (beginning at $25) as a financial base. Members will receive discounts for events, such as educational programs. A bicycle tour of Albert Kahn buildings in Detroit is planned for later this year.

MICHAEL G. SMITH

Hill Auditorium, the University of Michigan

ALBERT KAHN ASSOCIATES

For more information about the Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation, visit www.albertkahnlegacy.org.

Albert Kahn and Henry Ford

WIKIPEDIA One of the ironies of Kahn’s career is that his single most prominent client was Henry Ford, automotive pioneer, who was wellknown for public expressions of antisemitism in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. The newspaper published numerous articles about a conspiracy of Jewish bankers and Jews being the instigators of World War I. Eventually, a Jewish businessman sued Henry Ford for libel, there were protests of its contents by multiple organizations and the newspaper was closed. “Ford had no animus toward Jewish people individually,” says Michael G. Smith, a historian. Ford’s antisemitism stemmed from an experience with bankers when he sought a loan, Smith says. They wanted more control of the company than Ford was willing to provide. The bankers happened to be Jewish and from that encounter, Ford began to support a conspiracy theory about Jewish bankers and businessmen.

Eventually, Kahn would no longer meet with Ford, sending someone else in his place.

Why would Ford seek out a Jewish architect for his factories? It was basically due to Kahn’s ability to fulfill Ford’s ideas. “They had a great deal of respect for each other,” Smith says.

Factories at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries were multifloored, dark, airless buildings that were prone to fires. Ford wanted a factory that would accommodate his new assembly line rather than requiring cars to be built and transported between several levels of a building. Kahn was able to design a single-floor factory with lots of natural light, more floor space and better ventilation.

This resulted, in part, from his brother Julius’ development of an improved reinforced concrete that was stronger and required fewer support columns. Walls of windows provided much better lighting than other factories of the era.

This kind of construction provided a safer, more pleasant environment for workers and improved productivity. Kahn’s firm was also known for its efficiency and willingness to adapt to clients’ needs.