46 minute read

important modern works of art from a private collection, melbourne

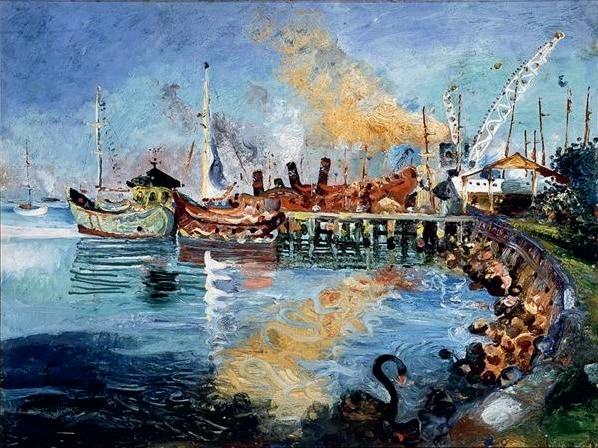

(1923 – 2000) OLD SHIPS AT WILLIAMSTOWN, 1959 (also known as ‘OLD HULKS AT WILLIAMSTOWN’) oil on canvas on composition board 86.5 x 103.0 cm signed lower left: Perceval

ESTIMATE: $400,000 – 600,000

PROVENANCE

Australian Galleries, Melbourne Miss Cara Black, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1959 Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 24 July 1988, lot 408 (as ‘Boats at Williamstown’) Private collection, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

John Perceval, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 17 March 1959, cat. 17 John Perceval: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings, Heide Park and Art Gallery, Melbourne, 10 July – 26 August 1984, cat. 52, p. 23 John Perceval: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 30 April – 12 July 1992, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 6 August – 20 September 1992 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Allen, T., John Perceval, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1992, p. 160

John Perceval Sulphur smoke, 1959 oil and tempera on composition board 90.8 x 121.0 cm Private collection

Amidst the turbulent war years of the 1940s, the art patrons John and Sunday Reed gathered a coterie of artists and writers around them at their farm cottage ‘Heide’ in the northern suburbs of Melbourne. Known now and forever as the Angry Penguins, their number includes Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester, Albert Tucker, Arthur Boyd and the youngest, John Perceval. Through the combination of drive and ambition, they and the Reeds collectively set a highly influential course through the trajectory of Australian post-war modernism. Incredibly, none of the artists ever graduated from art school and some had never even set foot within such an institution. They were, for the most part, self-trained but were also voracious readers absorbing ideas, suggestions and techniques that fed directly into the art they were making. For all but Hester, the 1950s brought fame and wealth, and Perceval’s Old Ships at Williamstown, 1959, is the perfect example of why this occurred, a life-affirming and boisterous view of the otherwise run-down port on Port Phillip Bay.

There is a seductive appeal to the Williamstown paintings with their swirling paint, rich colours and tumbling imagery which led critics to use such terms as ‘joie de vivre’ and ‘untrammelled joy’ to describe Perceval’s work. The noted historian Bernard Smith went further and saw links with American ‘action’ painting. Perceval believed such descriptions were simplistic, taking pains to explain instead that ‘at all times my work is primarily a response to the subject, to light and trees, air, people etc. Whatever success it may achieve is due to the desire to equate the vitality, the pulse of life in nature and the world around us.’1 Perceval, as noted, was not academically trained but had shown early talent. Forced into hospital for a year by a bout of polio when he had just turned fifteen, his story and a self-portrait were featured in a newspaper article in 1938 titled ‘Paralysed boy of 15 paints like a master.’2 The journalist had met Perceval by chance whilst visiting the wards and was immediately struck by the boy’s creativity and art knowledge noting that here was somebody with ‘talent oozing out of them.’3 The article also prompted the well known painter and teacher Arnold Shore to visit, advising him that to be serious, he must ‘make a drawing a day and a painting a week.’4 By the time he was an adult, Perceval’s drawings were uniquely his own, the complete antithesis of rigid academic emphasis on proportion and perspective. Instead, his lines become an integral component of his graphic work, twisting and spinning around the page, revealing a distinct kinship between these drawn marks and those of his brush.

Perceval served in the army during the early years of the war where he met Arthur Boyd and one of the pivotal partnerships in Australian art was formed. His new friend came from a family of artists who embraced the young man to such as extent that he married Boyd’s younger sister Mary. Perceval and Boyd founded the renowned AMB Pottery in 1944 and simultaneously embarked on a series of paintings informed

Arthur Boyd and John Perceval, 1943 photographer: Albert Tucker silver gelatin photograph 30.3 x 40.3 cm Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

by biblical tales and myths, underpinned by a deep admiration for such northern European artists as Rembrandt and Breughel. To truly understand how these early masters achieved their results, Boyd and Perceval studied Max Doerner’s The Materials of the Artist and their Use in Painting, published in 1934, using the book’s salient advice as a basis for their own experimentation. Following negative comments about his landscapes by John Reed, Perceval ceased painting to focus on his pottery but following the purchase of a Volkswagen beetle, and with Charles Blackman as an occasional companion, he began to travel further around Melbourne. Together, they ‘discovered’ picturesque Williamstown in 1955 which, as Perceval exclaimed, was ‘like finding Venice.’5 The resultant paintings formed the core of his solo exhibition the following year with Australian Galleries, who used the event to launch their business. The Gallery’s co-director Anne Purves later recalled the ‘overwhelming’ impact on first seeing the Williamstown works ‘where the aquamarine waters were edged by white lace as they washed up against the granite rocks, which formed the small havens for fishing boats.’6 As with Purves, the paintings struck a deep and positive chord with critics and collectors alike, and much of their number are now held in the collections of Australia’s state and national galleries.

Perceval returned to Williamstown in 1959 and painted a second, smaller series. In these he employed a higher key in his colours than that used in the earlier images, seen to full effect in Old Ships at Williamstown. As before, there is a palpable energy to these paintings – even a tang of salt air and diesel – but at their core is the artist’s distinctive technique and rigorous self-training, evident is such passages as the perfectly serried dashes that articulate the weed on the foreground ship’s ropes. Perceval’s design sets the cluster of the rusting ships against the sail of a passing yacht and, in the distance, the low profile of Melbourne city, under a sky full of scudding clouds, choppy on a base of Anne Purves’ lacy waves.

1. John Perceval, cited in Reed, J., New Painting 1952 – 1962, Longmans, Melbourne, 1963, p. 24. Bernard Smith’s ‘action painting’ quote appears on p. 99 2. Pimlott, F. L., ‘Paralysed boy of 15 paints like a master’, The Sun News Pictorial, Melbourne, 25 June 1938, p. 43 3. F. L. Pimlott cited in Barrett Reid, Of Light and Dark: the art of John Perceval, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1992, p. 10 4. Arnold Shore cited ibid., p. 9 5. Plant, M., John Perceval, Lansdowne Australian, Melbourne, 1971, p. 52 6. Anne Purves, unpublished memoirs cited in Field, C., Australian Galleries: the Purves family business. The first four decades 1956 – 1999, Australian Galleries, 2019, pp. 32-33

ANDREW GAYNOR

(1920 – 1999) PULPIT ROCK WITH FLAME TREES AND COCKATOOS, c.1982 oil on canvas 91.5 x 121.5 cm signed lower right: Arthur Boyd

ESTIMATE: $90,000 – 120,000

PROVENANCE

Art Galleries Schubert, Queensland Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in November 1987

‘The natural beauty of the Shoalhaven area caused Boyd to marvel constantly. His paintings are a celebration of grandeur and wonder of Nature. It is to Boyd’s credit that a single landscape can inspire such diversity of work. He gives us the impression that there are infinite possibilities, as long as we train ourselves to see.’1

Eager to rediscover his roots, his ‘Australianism’, after more than a decade abroad, in 1971 Arthur Boyd returned to the country of his birth to take up a Creative Arts Fellowship at the Australian National University in Canberra. Over the blazing summer of 1971 – 72, Boyd and his wife Yvonne were invited by the Sydney art dealer Frank McDonald to visit Bundanon for the weekend, staying at a home he shared on the south coast of New South Wales with art historian Sandra McGrath and her husband Tony. Here the artist’s joyful rediscovery of the Australian bush with its stark contrasts and clarity of light was nothing short of an epiphany, and thus in 1973, Boyd purchased the nearby property Riversdale on the banks of the Shoalhaven River. Once again the magic of the dour, untamed Australian landscape became the impetus for his art, and over the subsequent twenty-five years until his death in 1999, Boyd would dedicate himself almost exclusively to capturing the myriad moods of the Shoalhaven in images that are today imprinted upon the national psyche as some of our most beloved and iconic.

Soul-piercing in its beauty, the Shoalhaven region offered both refreshing solace for the artist’s world-weary eyes, and infinite potential as a subject – ‘the variation in the area with its great deep tones and high keys’ bearing strong affinities with music. As Boyd elaborated, ‘in the desert there is only one note, just one low singing note. In this landscape the tonal range – not tonal in the obvious sense of colour, but the actual fact of the horizon which can vary from very high to low to infinite, depending on your line of vision – makes it a greater challenge. It has a knife-edged clarity. Impressionism could never have been born here, but Wagner could easily have composed here. He could not have composed at Port Phillip Bay. In fact,’ he added with characteristic playfulness, ‘I actually think Wagner lived in the Shoalhaven.’2 Capturing the magnificent view from the Bundanon homestead, Pulpit Rock with Flame Trees and Cockatoos, c.1982 features the monolithic Pulpit Rock with its forward-tilting Phrygian cap profile, here symmetrically positioned and glistening in the searing midday sun, with the region’s ubiquitous cockatoos and flame trees dotted in the foreground. Central to Boyd’s Shoalhaven iconography during the eighties, the towering Pulpit Rock has not only been described by scholars as ‘his Rigi, his Mount Fuji, his Mont Sainte-Victoire’3 (alluding to the great mountain sequences of J.M.W. Turner, Hokusai and Cézanne), but moreover, compared to Monet’s various series of haystacks, poplars and the west front of Rouen Cathedral. Indeed, elaborating upon the religious significance imbued in his repeated use of this motif, Hoff suggests ‘in these paintings of Pulpit Rock set between sky and water in an ambience of luminous space, Boyd restates the theme of the cyclic element in nature that had occupied him in the forties.’4

Acknowledging that he is religious ‘in the sense that I am overawed by the marvellous things in the world and overawed by the awful things’,5 thus Boyd here pays homage to the sheer beauty, grandeur and wonder of Nature - all the while implying that unless steps are taken to preserve this wilderness for future generations, it will be destroyed. As he reflected, ‘I’d like to feel that through my work there is a possibility of making a contribution to a social progression or enlightenment. It would be nice if the creative effort or impulse was connected with a conscious contribution to society, a sort of duty or service. I think you have to make something which does involve concepts and ideas.’6

1. McKenzie, J., Arthur Boyd at Bundanon, Academy Editions, London, 1994, p. 42 2. Boyd, cited in McGrath, S., The Artist and The River: Arthur Boyd and the Shoalhaven, Bay

Books, Sydney, 1982, p. 62 3. Hoff, U., The Art of Arthur Boyd, Deutsch, London, p. 78 4. ibid. 5. Boyd, cited in McKenzie, op. cit., p. 43 6. Boyd, cited in Gunn, G., Arthur Boyd: Seven Persistent Images, National Gallery of Australia,

Canberra, 1985, p. 73

VERONICA ANGELATOS

(1920 – 1999) SLEEPING BRIDE, c.1967 oil and tempera on composition board 61.0 x 75.5 cm signed lower right: arthur Boyd

ESTIMATE: $70,000 – 90,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Sydney Savill Galleries, Sydney Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in June 2000

EXHIBITED

Arthur Boyd & John Olsen: Journeys through the Landscape, Savill Galleries, Sydney, 17 May – 14 June 2000, cat. 34 (label attached verso)

RELATED WORK

Bride in Landscape, c.1967, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 112.0 cm, private collection

Transformed from her former wide-eyed and full-bodied presence, Arthur Boyd’s symbolic bride is presented here, in Sleeping Bride, c.1967 as an ethereal echo of her previous embodiments. Bridging a stylistic and thematic gap between two chapters of Boyd’s oeuvre, this work features the painter’s recurrent bride in a desolate landscape observed only by two black crows. Alone, his protagonist now adopts the trope of a ‘figure in landscape’ that Boyd would use throughout the 1960s and 1970s, underpinned by Biblical and mythological narratives. Inspired by the discovery of European masterpieces following his migration to London in 1959, the artist began a series of inventive depictions of his bride, including Bride with Lover (Bride Turning into a Windmill), 1960, and Nude Turning into a Dragonfly, 1961. Franz Philipp in his 1967 monograph described these paintings as ‘forming an epilogue of mood rather than of narrative sequence, [they] call the fleeting apparitions of the phantom bride back into a land of timbered gullies and nocturnal ponds’.1

Following the critical acclaim of the series ‘Love, Marriage and Death of a Half-Caste’, commonly known as the ‘Bride’ series, depicting a poetic narrative of an ill-fated relationship, Boyd reused his former protagonist in later works as a means of further exploring psychological themes. When the initial series was presented by the artist in an exhibition at Australian Galleries in 1958, he labelled them as ‘Allegorical paintings’, partially masking the social commentary inherent in his subject matter, instead highlighting the exploration of universal themes of love, fear, and identity and alluding to thematic developments to come.

Revisiting the Bride series with whimsical variations throughout the 1960s, Boyd explored the existential limits of his leading lady. Continuing the constant physical and psychological transformations affecting her in his original series, this painting, Sleeping Bride, is an epilogue in which the bride is listless, exiled and almost formless in the physical absence of her departed lover. Painted concurrently with the artist’s Nebuchadnezzar series and featuring similar mise-en-scene and emblems, this bride is presented on the cusp of metamorphosis. She is loosely painted; the thin glazes of her white matrimonial regalia are physically permeated by the strong ochre colour of the central Australian earth. No longer floating in a Chagall-like manner, she is prostrated in the foreground of the landscape, becoming one with it. While the landscape that this bride inhabits is barren, its cavernous forms hint at underlying eroticism left over from Boyd’s original series.

Featuring the expressive brushstrokes of his later works, Sleeping Bride can be easily read as a portrait of the flawed hero, a painterly version of a theatrical soliloquy. The bride appears at once as herself but also as a tragic goddess of classical myths, such as the chaste Diana or a bathing Susannah. An example of pure artistic and poetic experimentation, Sleeping Bride is a psychological extension of Boyd’s famous series, seeking to illustrate less tangible themes of the vicissitudes of human emotion.

1. Philipp, F., Arthur Boyd, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 92

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

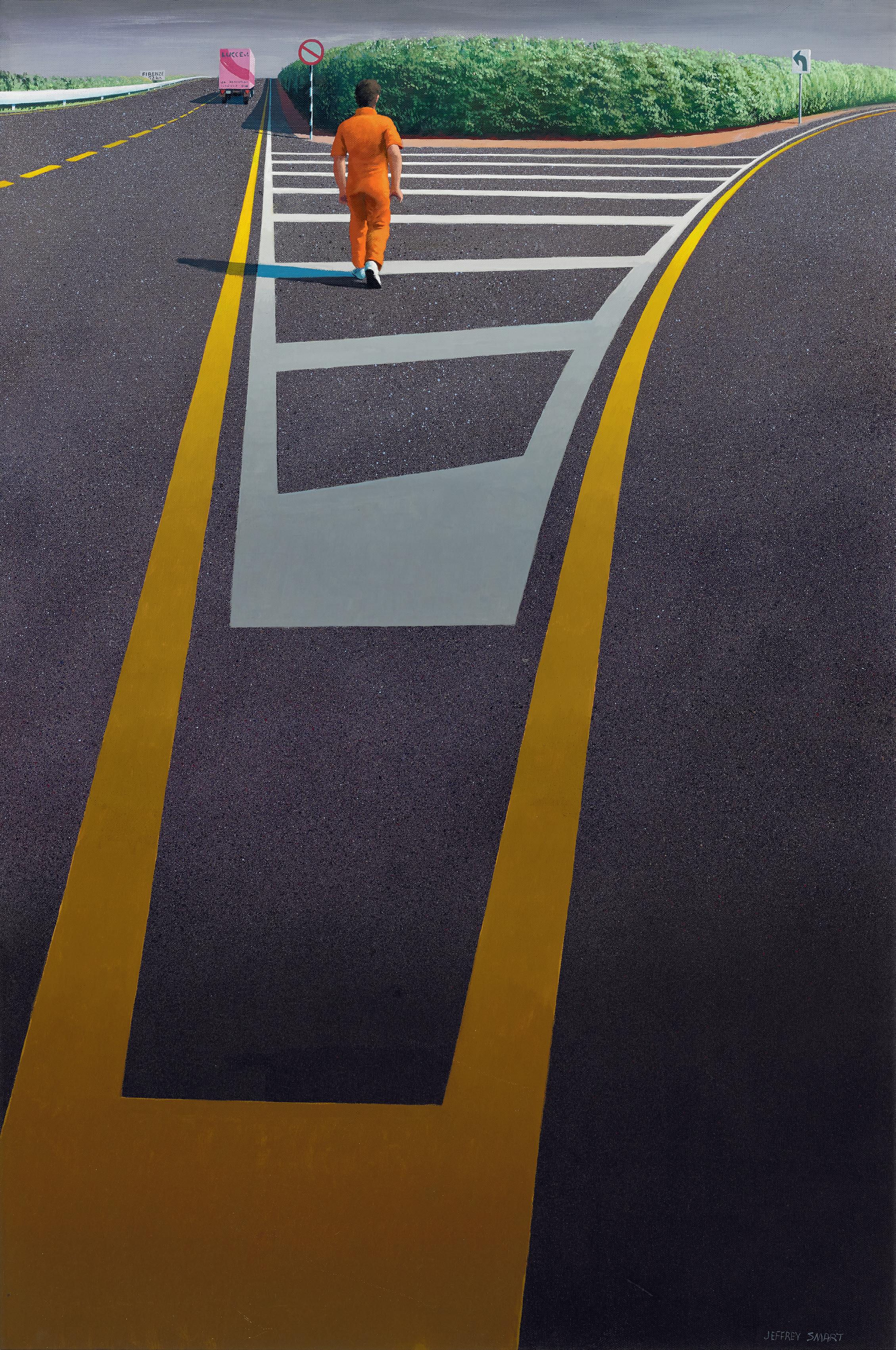

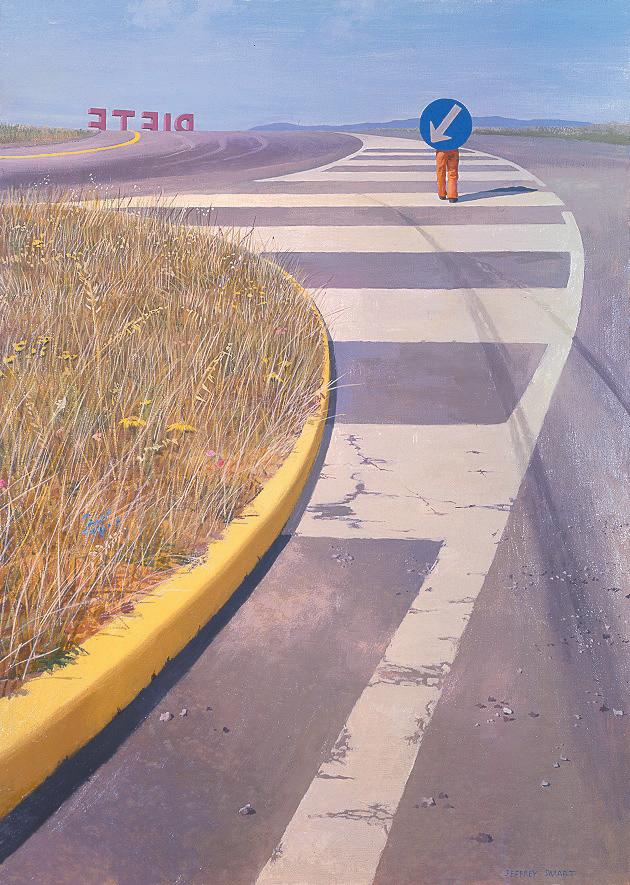

(1921 – 2013) THE AREZZO TURN–OFF II, 1973 oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas 119.0 x 79.0 cm signed lower right: JEFFREY SMART

ESTIMATE: $800,000 – 1,200,000

PROVENANCE

Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney Private collection, Sydney, acquired from the above in 1973 Australian Galleries, Melbourne (label attached verso) Private collection Christie’s, Melbourne, 27 November 2001, lot 69 Private collection, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

Jeffrey Smart, Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney, 30 November – 31 December 1973, cat. 10 Jeffrey Smart: A Review., The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 17 June – 8 August 1982, cat. 38 Urban and Urbane: paintings, drawings & prints, Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Sydney, 28 June – 23 July 1994, cat. 23 (label attached verso) Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 27 August 1999 – 6 August 2000, cat. 44, and touring to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne Australian Galleries, Melbourne, September 2000 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, cat. 618, pp. 76, 113 McDonald, J., Jeffrey Smart / Paintings of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, cat. 79, p. 157 McCulloch, A & S., The Encyclopedia of Australian Art, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 651 (illus.) Capon, E., Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, cat. 44, pp. 21, 135 (illus.), 208

RELATED WORK

The Arezzo Turn–off I, 1973, synthetic polymer paint and oil on canvas, 80.0 x 100.0 cm, private collection Sketch for The Arezzo Turn–off II, 1973, gouache on paper, 21.0 x 18.0 cm, private collection

We are grateful to Stephen Rogers, Archivist for the Estate of Jeffrey Smart, for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

Jeffrey Smart’s residence, Posticcia Nuova, Arezzo, Tuscany photographer unknown © The Jeffrey Smart Archive

‘Many of my paintings have in their origin a passing glance. Something catches my eye, and I cautiously rejoice because it might be the beginning of a painting. Sometimes it’s impossible to stop and sketch because I saw it from a train or a fast-moving car on the autostrada. And it can happen that when I go back to that place, I wonder what on earth it could have been that enchanted me – it isn’t there. Enchantment is the word for it…’1

Undoubtedly one of the great paradoxes of Jeffrey Smart’s widely acclaimed legacy is that symbols of modernity, urban pressure and activity such as freeways, road signs and trucks should be imbued with an aura of stillness, order and timeless serenity more reminiscent of the Italian Quattrocento painting he so admired. For while drawing inspiration from the urban environment that has flourished in Italy since the Second World War, Smart’s immaculate compositions invariably bear no trace of the chaos or randomness of the world from which they derive. Rather, meticulously distilling his subject of the modern city down to its purely formal qualities in a manner echoing his artistic mentor Cézanne, Smart encourages his audience to see the ‘everyday’ with fresh eyes – to discern beauty in the most unprepossessing, unromantic of subjects. With its signature motif of a broad sweeping bitumen arterial seen from a low perspective and disappearing to an unknowable destination beyond, The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 offers a magnificent example of the mastery and miracle of Smart’s art, encapsulating his unique ability ‘to elevate mundane familiarities… to the status of semi-mystic icons’.2 Redolent with his love of ambiguity and seductive in its ‘super realism’, indeed the work is Smart at his finest, betraying strong iconographic affinities with some of the artist’s most celebrated works, including the iconic The Guiding Spheres II (Homage to Cézanne), 1979 – 80 (private collection).

Having emigrated to his adopted homeland of Italy in 1963, in early 1971 Smart acquired ‘Posticcia Nuova’, a rustic farmhouse in the heart of Tuscany, near a village called Pieve a Presciano, not far from Arezzo. Proximate to the masterpieces of Renaissance master Piero della Francesca whose passion for stillness, light and geometry famously inspired him, it was to be Smart’s home for the rest of his life. A generous financial gift bequeathed by his dear friend and fellow artist, Mic Sandford, upon his sudden tragic death only weeks earlier, subsequently enabled Smart to undertake renovation works to make the old farmhouse habitable and importantly, to transform the two-storey hayloft into two bright spacious studios, one for himself and another for his partner at the time, Melbourne surrealist artist, Ian Bent. Immersed in this delightfully idyllic ambience within the picturesque olive groves,

Jeffrey Smart The Guiding Spheres II (Homage to Cezanne), 1979 – 80 oil on canvas 55.5 x 64.7cm Private collection © The Jeffrey Smart Archive

villas and gardens of the Tuscan countryside, the first two or three years in particular at Posticcia Nuova were a period of tremendous elation for Smart. As he reminisced, ‘Life was pretty good at Posticcia Nuova... the sun poured into the loggia during winter, and went up high above us in summer, leaving the whole place cool and shaded… We would work to music. Down in his studio Ian would play records and I was treated to Mahler, and lots of Bruckner which I’d not known, as well as the three Bs – Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. It was very pleasant not knowing what music was coming next…’3

Not surprisingly perhaps, these halcyon days also heralded the emergence of some of the most compelling and commercially successful paintings of Smart’s career. Reviewing the artist’s exhibition of recent work at South Yarra Gallery in November 1972, The Age art critic Patrick McCaughey declared the group to be ‘better than he’s ever done before’, enthusiastically welcoming ‘the new access in Smart’s quality’.4 Notably, the National Gallery of Victoria purchased the famous Factory and Staff, Erehwyna, 1972 from the show, while Painted Factory, Tuscany, 1972 entered the Fairfax collection. The following year when The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 was unveiled at Smart’s solo exhibition at the Rudy Komon Gallery in Sydney, the display of fourteen major canvases and eight studies was similarly applauded as his most ambitious and comprehensive to date. Significantly, several paintings were acquired by public institutions and have now become some of Smart’s most well-known images, including Truck and Trailer Approaching a City, 1973 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); The Traveller, 1973 (Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art); Bus Terminus, 1973 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); Near Knossos, 1973 (South Australian College of Advanced Education, Adelaide); and The Golf Links, 1971 and Over the Hill, Bicycle Race, 1973 (both University of Sydney Art Collection, Sydney). That the paintings unveiled in this legendary show still remain universally considered among the artist’s most important is attested by the inclusion of five (including The Arezzo Turn-Off II) in the groundbreaking retrospective organised by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1999, while the aforementioned six from public institutions will feature in the forthcoming Jeffrey Smart exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (December 2021 – May 2022).

Addressing the ostensible incongruity of depicting the Italian autostrada when surrounded by the beauty of the Tuscan countryside, Smart explained that the latter ‘…environment is conducive for work, and on my frequent forays to Arezzo and Florence I see a lot of that modern world which I like to paint.’5 As he elaborates further in his

Jeffrey Smart Near Ponticino, 1978 oil on canvas 91.0 x 66.0 cm Private collection © The Jeffrey Smart Archive

engaging memoir, Not Quite Straight, ‘Italy was even more beautiful seen from the autostrada – no hoardings were permitted; the only signs were those needed for the traffic and I found them beautiful, they were so well designed.’6 Although unmistakably derived from a moment glimpsed by Smart during one of his many journeys on the A1 autostrada between Rome and Florence, The Arezzo Turn-Off II does not offer a faithful depiction en plein air of an exact scene. Rather, the work here presents a composite image – constructed from the complex weaving of motifs, symbols and disparate elements recalled from either real-life locations or gleaned from other artworks, both his own and those painted by artists whom Smart admired. Accordingly, the genesis for The Arezzo Turn-Off II may be traced back to spontaneous, lucid sketches made by Smart while sitting in the front seat of his car during his travels on the autostrada, little visual notes that captured his initial sense of enchantment with the scene and would later become the aidemémoire for his painted studies, including the gouache Sketch for The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 (private collection). Subsequently embarking upon his first exploration of the subject with the full-scale canvas, The Arezzo Turn-Off I, 1973 (private collection) in which he employed a horizontal format and experimented for the first time with the technique of spray-painting to emulate the bitumen surface texture, Smart then fully resolved his compositional structure in the present work – which notably represents one of only a handful undertaken by the artist in the more dramatic vertical format. During his lifetime, Smart repeatedly avowed that his only concern was ‘putting the right shapes in the right colours in the right places’7 and indeed, in their deliberate orchestration his paintings have often persuasively been compared to the Italian films of the 1950s and 60s by Fellini, Antonioni and Pasolini which – similarly exploring the beauty of post-war Italian cities – typically feature composed shots distilled for poetic effect. Yet unlike compositions that betray a sense of evolvement, Smart’s paintings bear a remarkable quality of planned completion that is usually aided by a single dominant feature – in the present case, the broad arc of the highway arterial which literally sweeps the viewer from their low viewing point in the foreground and leads them to the dramatic horizon and mysteries of an unseen vista beyond. Such compositional doctrine in which a single element provides both the foundation and the dynamic may be discerned earlier in Smart’s oeuvre in works including Wasteland I, 1945 (private collection); Keswick Siding, 1945 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and Approach to a City III, 1968 (private collection); and reaches its fullest dramatic expression towards the end of the seventies in Near Ponticino, 1978 (private collection) and quintessentially, The Guiding Spheres II (Homage to Cezanne), 1979 – 80 (private collection). As with these consummate later works, here the apparent simplicity of the compositional structure in The Arezzo TurnOff II belies its overall tension and complexity, created by a series of perplexing visual conundrums.8 For example, the viewer’s perspective

Jeffrey Smart Arezzo Turn–Off I, 1973 oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas 80.0 x 100.0 cm Private collection © The Jeffrey Smart Archive

here is impossibly low, lower than that of a pedestrian or passenger in a car; it is broad daylight and yet the expected busy freeway is completely empty, save for the pink Lucce-branded truck disappearing over the horizon; and are we to continue along the road to Florence or take the turn-off on the right?

Like the best of Smart’s achievements, The Arezzo Turn-Off II beguiles both the eye and mind, remaining infinitely suggestive but revealing nothing. Although his works have frequently been construed as bleak commentaries on a society alienated by technology or a world impoverished by mass-produced architecture, such pessimistic interpretations would seem to negate Smart’s own professed intentions for his art. For as Barry Pearce elucidates, his paintings ‘…are, at the end of the day, expressions of himself. Container trucks which pollute cities, highways which have displaced communities, and modulised buildings which have absolved individuals from caring about each other are not in themselves beautiful. They cannot be, except that from the tranquility of his eighteenth-century farm in Tuscany, Smart has made them beautiful by extracting time and noise and pain.’9 Relentlessly asserting his faith in the timeless beauty he perceives amidst the clutter of contemporary life, Smart’s paintings convey rather, a rich sense of optimism despite their occasional uncertainties – a poignant reminder that the things which seem upon first glance to reflect a brutality to the soul can become, ironically, a source of wonder.10 As Quartermaine ultimately reiterates, ‘…Smart’s paintings are not to be looked through but looked at. If we look through them, we find only the preconceptions we brought with us – by looking at them with the attention they demand we can experience their world.’11

1. Smart cited in Capon, E., et al., Jeffrey Smart: Drawings and Studies 1942 – 2001, Australian

Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2001, inside cover 2. Capon, E., ‘Still, Silent, Composed: The Art of Jeffrey Smart’ in Jeffrey Smart, Art Gallery of

New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, p.16 3. Smart, cited in Smart, J., Not Quite Straight a memoir, William Heinemann Australia,

Melbourne, 1996, p. 414 4. McCaughey, P., ‘Australian Painting in Familiar Custody’, The Age, 15 November 1972, p. 2 5. Smart cited in O’Grady, D., ‘Jeffrey Smart; loitering with intent’, Sydney Morning Herald,

Spectrum, 25 November 1995 6. Smart cited in Smart, 1996, op. cit., p. 386 7. Smart cited in Jeffrey Smart, 1999, op.cit., p.14 8. See Smith, G., catalogue entry for lot 16, The Arezzo Turn-Off I, 1973 in Smith and Singer,

Important Australian and International Art, Sydney, 20 April 2021, p. 53 9. Pearce, B, ‘Out of Adelaide’ in Jeffrey Smart, 1999, p. 32 10. Ibid. 11. Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, p. 78

VERONICA ANGELATOS

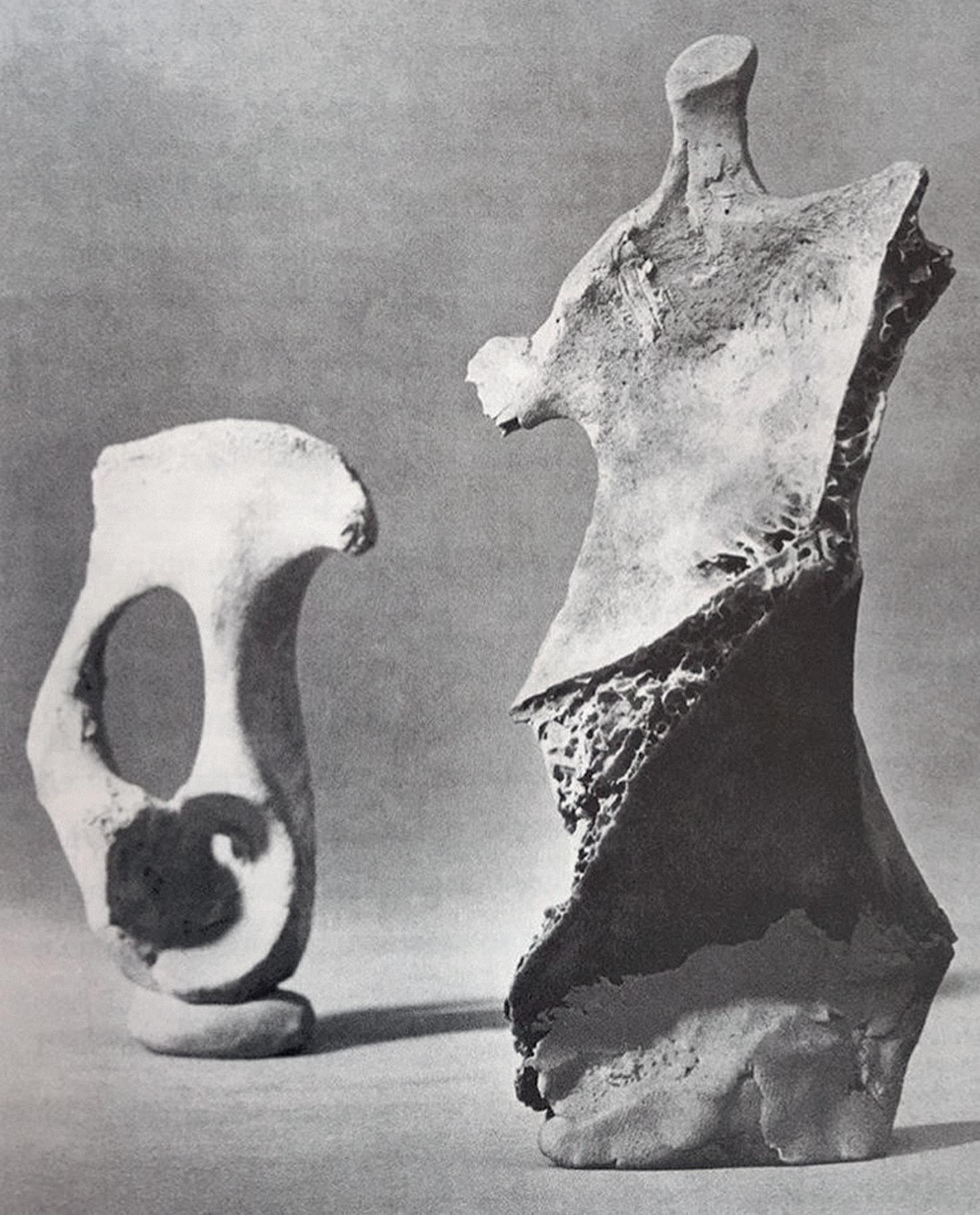

(1898 – 1986, British) MAQUETTE FOR RECLINING FIGURE: CIRCLE, 1983 bronze, brown patina 7.5 x 15.5 x 4.5 cm edition: 8/9 signed and numbered on base: Moore 8/9

ESTIMATE: $60,000 – 90,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, USA, acquired directly from the artist Lillian Heidenberg Fine Art, New York (label attached to base) Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in December 2003

EXHIBITED

Henry Moore, Fonds Hélène & Édouard Leclerc pour la Culture, Landerneau, France, 10 June – 4 November 2018 (another example)

LITERATURE

Bowness, A., (ed.) Henry Moore, Complete Sculpture 1949 – 54, London, 1986, vol. 6, cat. LH 902, pl. 127 (illus. another example)

RELATED WORK

Another example of this cast is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, United Kingdom Reclining Figure: Circle, 1983, plaster, 7.5 × 15.7 × 4.4 cm, held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, United Kingdom Reclining Figure: Circle, 1983, bronze, 43.2 x 88.9 cm, edition of 9, held in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Henry Moore OM CH (1898 – 1986) is regarded today, as he was during his lifetime, as one of Britain’s greatest Modernist artists, with his sculptures known and admired around the world. Approaching the subject of the reclining human form with a radical revision of figurative representation, Moore came to symbolise the resilience and inventiveness of the English people in the wake of the wars of the early 20th century. Founded on organic and mineral forms, his sculptures contain familiar shapes that are then transformed and rearranged into semi-abstract figurative compositions, anonymous and universally resonant. Almost completely divorced from a recognisable figurative form, Reclining Figure: Circle’s revision of this pose is bold and authoritative, unifying the many threads of artistic inquiry Moore had followed throughout his career.

Maquette for Reclining Figure: Circle, 1983 is a small editioned bronze sculpture by Henry Moore, cast from an original plaster carving (LH902, plaster, now held in the Henry Moore Foundation), and later enlarged into another editioned bronze sculpture (LH903), although never into a monumental format. A quintessentially modern artist, Henry Moore created sculptures which rarely refer to their geographical environment, and can exist independently as small objects, to inhabit in private spaces as well as in grand, public ones.

Reduced to the most condensed ratio of proportions and directional lines, the format of a reclining female figure with knees bent, resting on her elbow, is only barely discernible within this maquette. Moore has created a dramatic transformation of smooth curves, crests and pointy accretions into the silhouette of a human being. Although modest in size, paradoxically, Henry Moore’s composition of Reclining Figure: Circle was constructed with the intention of monumentality. As the artist himself explained: ‘everything I do is intended to be big, and while I’m working on the models, for me they are life size. When I take one in my hand like this, I am seeing and feeling it as life size… so in my mind there’s never any change of scale at all’.1 Moore’s oeuvre is underpinned by the concepts of transformation and metamorphosis, using organic objects as stimuli, combined with a Jungian theory of archetypal images and collective unconscious.2 His works in sculpture, drawing and print reveal this tightly cohesive visual thesis. From the 1930s, Moore sought the true essence of form within nature and mathematics. He used the ‘raw materials’ of found items such as weathered flint stones, shells, and bones, displayed in vast collections on the shelves of his maquette studio in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. The 1930s were a period of extraordinarily creative experimentation for Moore, sadly suspended in a preparatory state over the years of the second world war and only revisited much later in works such as this Reclining Figure: Circle.

Pencil and ink drawings held in Moore Foundation demonstrate the clear development of ideas through a progressive reduction of form. Photographs and drawings from his studio dating back at least to 1961 reveal the exact organic stimulus for Reclining Figure: Circle, a hipbone of a sheep [fig. 1]. This shape appears in several charcoal and ink studies and finally was copied in 1983 into the plaster sculpture from which this bronze was cast. The clearest example can be found in Idea for sculpture: Bone Form, 1983 (HMF 83 (129) and HMF 83(77)), although scholars at the Henry Moore Foundation have suggested these may have been drawn from the finished sculpture as opposed to being preparatory sketches.3

The classical ideal of the reclining nude was a recurrent theme within Henry Moore’s oeuvre, generating many masterpieces, including Reclining Figure, 1935 – 1936 (elmwood, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo) and Reclining Figure, 1951 (bronze, National Galleries of Scotland). With its advanced formal abstraction, the innovation that distinguishes Maquette for Reclining Figure: Circle from previous investigations of the format was the inclusion of two holes directly copied from the mammalian pelvic bone in Moore’s studio: the perforation of the obturator foramen and the ball socket joint of the

Bone forms, ideas for sculpture Henry Moore’s studio, c.1961 photographer unknown illus. in Henry Moore 1898 – 1986, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1992, p. 20

femur. The spherical indentation of this ball socket, with sharp edges around the rim, is the circle of this work’s title. The original plaster form of Reclining Figure: Circle was scored and filed to mimic the texture of the original bone, contrasting with the rounded rhythmic arches that anchor the sculpture to its base and its uppermost crests. When cast in bronze, these textures remain apparent, only now gleaming with a dynamic tension. Reclining Figure: Circle, while fixed in its heavy bronze materiality, is delicately poised on three points of contact, and the viewer’s eye is instinctively drawn through these voids and back through the form, giving multiple points of view of the form at once, verifying Moore’s claim that ‘The hole connects one side to the other, making it immediately more three-dimensional.’4

1. Henry Moore, interview with Donald Hall, 1960, quoted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore:

Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p. 208 2. Calvocoressi, R., director of the Henry Moore Foundation, quoted in ‘Henry Moore

Wunderkammer Origin of Forms’, Gagosian, London, February – April 2015, p. 78 3. Henry Moore Foundation online catalogue [https://catalogue.henry-moore.org/objects/12112/ reclining-figure-idea-for-sculpture?ctx=7e72c6f95f9658ebf12380b7d5b91f7d3aec85da&i dx=192] (accessed 4/11/21) 4. Moore, H., ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, London, 18 August 1937, pp. 338 – 40

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

born 1932, Columbian RECLINING WOMAN (DONNA SDRAIATA), 2009 bronze 54.5 x 27.0 x 22.0 cm edition: 6/6 signed and numbered at base: Botero 6/6

ESTIMATE: $300,000 – 500,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, acquired directly from the artist David Benrimon Fine Art, New York Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in November 2012

Accompanied by a copy of the original certificate of authenticity from the artist.

‘In the history of sculpture, eighty percent of the subject matter has been a woman, either reclining standing or seated. It is a great tribute paid to the most beautiful form of nature. The interesting thing is that in returning to the same subject, you always say something different.’1

Renowned Colombian painter and sculptor Fernando Botero almost requires no introduction, he’s an enduring popular hero of Latin America. The whimsical stylisation of his rotund figures and objects have coined a new term, Boterismo, and are instantly recognisable from his extensive oeuvre of drawings, paintings and sculptures. While Botero’s career began with painting, it was through the medium of sculpture during the mid-1970s that his fascination with the plasticity of inflated, curvaceous forms was best conveyed. In bronze and marble, the confluence of taut volumes and smooth shining surfaces is masterfully used by Botero, and most often applied to anonymous and archetypal female forms. With blank expressions and unfurrowed brows, the inhabitants of Botero’s universe are placid and languorous, occasionally represented smoking a cigarette or holding an apple. Donna Sdraiata, 2009 is a magnificent example of the sculptor’s reclining female nudes. Featuring a simple composition upon a cloth, Botero highlights the smooth surfaces and soft, supple textures paradoxically conveyed by the gleaming bronze.

Botero spent three years living and working in Italy at the start of his career, and having imbibed this visual culture, Renaissance tropes began to inform his artistic compositions in painting and sculpture. Instead of working live models, Botero relies on his visual memory and other artistic appropriations. In reprising the classical theme of the reclining female nude, Botero found the perfect vehicle to explore again and again an overtly sensuous female form, working within the pre-determined confines of well-known theme of Western Art history. He has created many versions of the Donna Sdraiata, the reclining woman, between 1984 – 2009, often in a monumental size, including Reclining Nude, 1984 (Birmingham Museum of Art, USA and Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Japan), Reclining Woman, 1993 (Kunstmuseum Leichtenstein, Lichtenstein) and Donna Sdraiata, 2003 (Ekebergparken, Olso, Norway), sculptures which are all closely related to one another.

The plump limbs of these languid women caught in their reverie spill over the edges of their plinths. Many of Botero’s sculpted rectangular bases also have a plump, pillowy aspect, emphasising the inherent material contradiction with the bronze and marble of which they are made. With an almost comic disregard for exact proportions, Botero emphasises the physical and plastic impact of a generous figure rather than the elegant poise expected of a classical reclining nude. This Reclining Woman, unlike her more relaxed and licentious counterparts, is alert, poised to leap up. While her gaze is loftily disengaged, she is modest, curled on her side, with an arm covering her chest. Innocently removed from the dangers of the real world, Botero’s figures are unaware of our presence, and the viewer necessarily becomes a voyeur.

Botero comes from and depicts in turn Colombian mestizo culture – hybridising Castilian conservatism and elements of indigenous Amerindian culture, striving to humanize visual representations of Latin American culture.2 Considered by some academics to be humorous caricatures of the upper classes of the conquistadors of Latin America, Botero’s figures display humanist ideals in their accessibility and anonymity. Botero’s art is democratic, easily legible, and accessible to viewers of all ages, particularly when publicly installed and displayed in a monumental format. While the influence of classical Western Renaissance art is evident in Botero’s works, he remains engaged with Latin American concerns and subject matter, invoking the ‘atmospheres and characters of all the paisa cultures in which [he] has lived’.3

1. Fernando Botero, March 2021, quoted in Zest and Curiosity, [https://www.zestandcuriosity. com/2021/01/03/botero/] (accessed 4/11/21) 2. ibid. 3. Chow Kian, K., and Willie, V., Botero in Singapore, Singapore Art Museum, 2004, p. 30

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

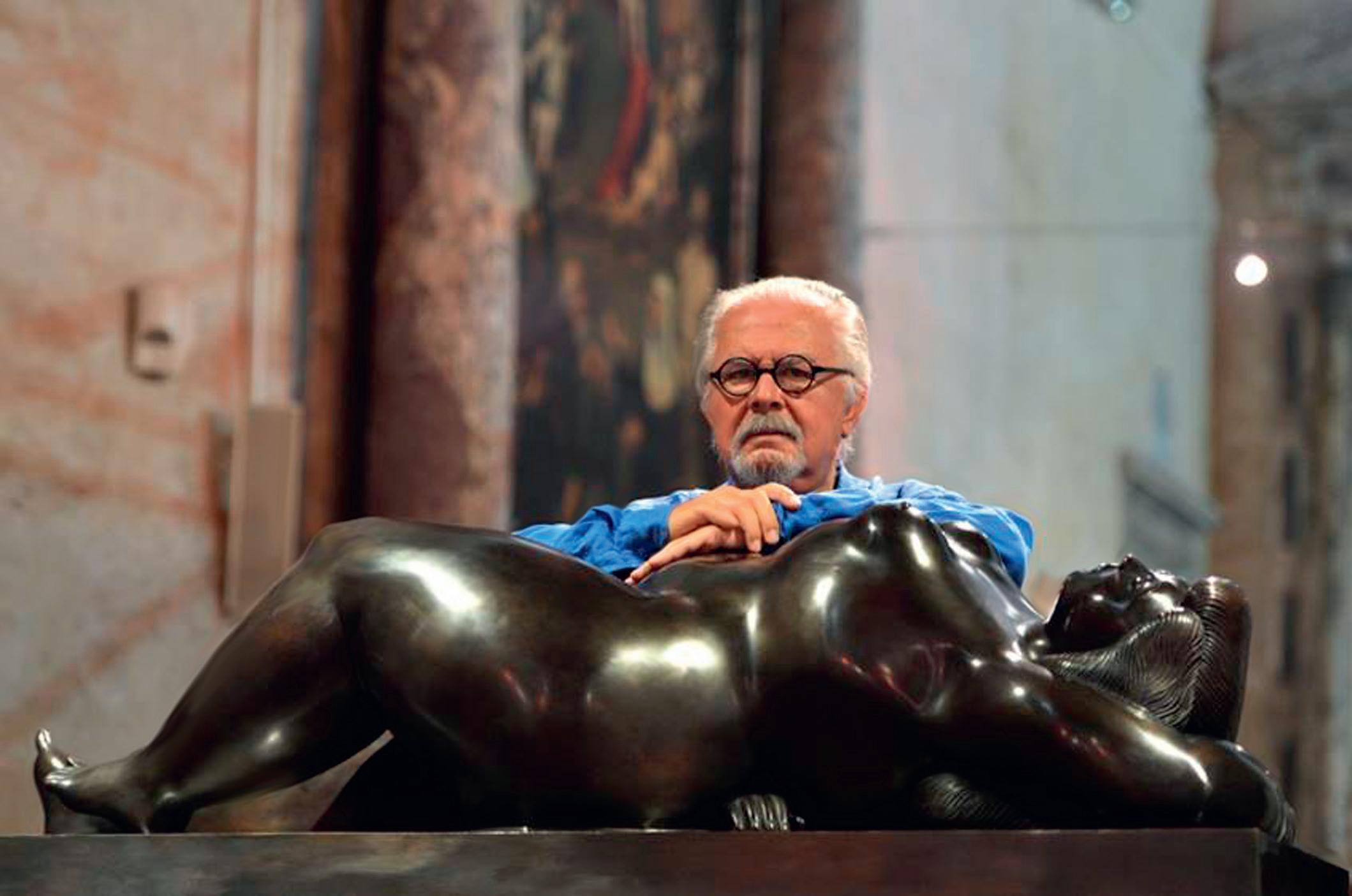

Fernado Botero poses next to one of his sculptures in Santo Augustino’s Church in Pietrasanta, Tuscany, prior the opening of ‘Fernando Botero: designer and sculptor’ exhibition on July 6, 2012 photographer: Gabriel Bouys AFP Photo / Getty Images

(1925 – 2013, French) LA MARATHONIENNE, 1981 cast 2004 steel with rust patina 190.0 x 127.0 x 74.0 cm edition: 5/8 + 4 APs signed and numbered at base: HIQUILY 5/8

ESTIMATE: $80,000 – 120,000

PROVENANCE

Galerie des Lices, Saint–Tropez, France Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in August 2006

EXHIBITED

Hiquily, Fer, Galerie Ratton–Hourdé, Paris, September – October 2007 (another example) Philippe Hiquily, Galerie LOFT, Paris, September – November 2008 (another example) Philippe Hiquily et Wang Keping: Sculptures et Sensualité, Galerie LOFT, Paris, May 2009 (another example) BRAFA, Tour et Taxis, Brussels, 21 – 30 January 2011 (another example) Hiquily au Donjon de Vez, Vez, France, 4 July – 14 September 2014 (another example) Hiquily, Galerie Laurent Strouk, Paris, 10 March – 9 April 2016 (another example) Philippe Hiquily, Musée de la Vallée de la Creuse, Éguzon, France, 2 June – 22 September 2019 (another example)

LITERATURE

Chen Yen–Fong, Hiquily, Erotisme, Mouvement et Humour en Sculptures, Artist no. 112, Taiwan–Taipei, September 1984, p. 170 (illus. another example) Art dans la ville – 100 oeuvres, Vitry–Sur–Seine, France, 1988, p. 84 (illus. another example) Joncquet, F., Hiquily, Éditions du Cercle d’Art, Paris, 1992, pl. 101, p. 126 (illus. another example) Vinot, M., Jouffroy, A., Roudillon, J–F., Hiquily, T., Philippe Hiquily, Catalogue Raisonné: 1948 – 2011, Loft Editions, Paris, 2012, vol. I, cat. 358, pp. 265 (illus. another example), 269

RELATED WORK

La Marathonienne, 1981 – 82, corten steel, 500.0 cm height, public sculpture, Vitry–sur–Seine, France

French post-war and contemporary artist Philippe Hiquily worked primarily in the field of sculpture over a career spanning 60 years. Almost immediately after his graduation from the École des Beaux Arts in Paris in 1959, his modern assemblages were collected by national museums in America (the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art) and in France (Centre Pompidou) and later were installed in public urban areas and private homes around the globe.

Fiercely independent and with a singular aesthetic voice, Hiquily created surrealist figurative sculptures in tin and brass based on the female form, examples of which were keenly collected from his first exhibition in New York City, at The Contemporaries gallery, in 1959. Later, following in the footsteps of Spanish modernist Julio Gonzales and American kinetic sculpture pioneer Alexander Calder, Hiquily’s suite of geometric cut ironwork sculptures became monumental installations, the most well-known of which is La Marathonienne.

With a title referring to an ancient Greek female marathon-runner, La Marathonienne’s body is composed of disjointed geometric planes. Devoid of identifying features beyond her stylised breasts, she becomes an archetypal woman. The cut sheets of metal that comprise the limbs of Hiquily’s running woman span out from central axis. They are visible from every angle, and the windows pierced through the sheets create multiple simultaneous views of the figure metaphorically at the apex of her physical activity. Although La Marathonienne is undeniably static and monumental as opposed to being kinetically animated like Hiquily’s 1960s girouettes, the suggested rapid motion of her athletic pose is suspended in space and time.

Initially conceived in 1981 as a commission for public sculpture in the Parisian suburb of Vitry-Sur-Seine, the first example of La Marathonienne stands tall at 6m high of rusted steel. Fittingly, Hiquily’s icon of a modern sportswoman was installed in front of a sports centre, the Complexe Sportif Georges Gosnat. She was revisited much later by the artist, and in 2004, La Marathonienne was cast in editions of 8 in several sizes, some painted with black epoxy, and others, like this one, fabricated from steel, each recorded in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, published in 2012. In addition to appearing in prominent outdoor sculptural installations in Paris, including in Place Saint-Germaindes-Près in 2010, La Marathonienne was beamed to a wider global audience through the American Showtime television series, Billions, where it was installed overlooking the bay of Villefranche-sur-Mer. She is a modern version of the monumental statue, a triumphant expression and celebration of the physical potential of the human body.

With a bold graphic geometric abstraction of the figure inspired by hieratic ancient Cycladic figurines, La Marathonienne’s proportions are exaggerated and reduced into a matrix of sweeping curves, sharp lines and delicately counter-balanced points. With Hiquily’s most profound geometric abstraction, La Marathonienne, and her angular, crouched counterpart, l’Épicurienne, while both figurative constructions, bear little resemblance to the artist’s former bulbous and insect-like female idols, Objets Mères. Instead, their folded and cut-out structures are reminiscent of paper snowflakes, cut and then unfurled around a central axis. The tension of open-work between La Marathonienne’s curves and straight edges animates the construction with a sense of lightness and movement that belies the sculpture’s material nature. Dr Malika Vinot, editor of Hiquily catalogue raisonné, describes this figure as ‘immortalised in an ultimate moment of grace, both strong and untameable, rendered vulnerable by the stolen moment in which she seems suspended.’1

1. Vinot, M., Jouffroy, A., Roudillon, J-F., Hiquily, T., Philippe Hiquily, Catalogue Raisonné: 19482011, Loft Editions, Paris, 2012, vol. I, p. 269

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

Philippe Hiquily with a monumental version of ‘La Marathonienne’, Paris, c.1982 photographer unknown The Ferus Gallery, France

prospective buyers and sellers guide

ALL PARTIES ARE STRONGLY URGED TO READ THE CONDITIONS OF AUCTION AND SALE INCLUDED IN THIS CATALOGUE

1. PRIOR TO AUCTION

CATALOGUE SUBSCRIPTIONS Catalogues can be obtained at Deutscher and Hackett offices or by subscription (see the Catalogue Subscription Form at the back of this catalogue or online for more information).

PRE-SALE ESTIMATES The price range estimated against each lot reflects the opinion of our art specialists as to the hammer price expected for the lot at auction and is informed by realised prices for comparable works as well as the particularities of each lot including condition, quality, provenance and rarity. While presale estimates are intended as a guide for prospective buyers, lots can be sold outside of these ranges. Pre-sale estimates include GST (if any) on a lot but do not include the buyer’s premium or other charges where applicable.

RESERVES The reserve is the minimum price including GST (if any) that the vendor will accept for a lot and below which the lot will not normally be sold.

PRE-AUCTION VIEWINGS In both Sydney and Melbourne pre-auction viewings are scheduled for several days in advance of each auction. Deutscher and Hackett specialists are available to give obligation free advice at viewings or by appointment and prospective buyers are strongly encouraged to thoroughly examine and request condition reports for potential purchases. Pre-auction viewings are open to the public and are free to attend.

SYMBOL KEY ▲ Unless ownership is clearly stated in the provenance, this symbol is used where a lot is offered which Deutscher and Hackett owns in whole or in part. In these instances, Deutscher and Hackett has a direct financial interest in the property or means that Deutscher and Hackett has guaranteed a minimum price. ● Used to indicate lots for sale without a reserve.

EXPLANATION OF CATALOGUING PRACTICE AND TERMS All information published in Deutscher and Hackett catalogues represent statements of opinion and should not be relied upon as fact. All dimensions are listed in centimetres, height before width and are approximate. All prices are in Australian dollars.

ARTIST’S NAMES All reference to artists make use of common and not full names in accordance with the standards outlined in the National Gallery of Australia reference publication Australian Art: Artist’s working names authority list. For instance, John Brack rather than Cecil John Brack; Roy de Maistre rather than Leroy Leveson Laurent De Maistre; Rosalie Gascoigne rather than Rosalie Norah Gascoigne.

Terms used in this catalogue have the meanings ascribed to them below:

a. NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, a work by the artist. b. Attributed to NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, probably a work by the artist, in whole or in part. c. Circle of NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, a work showing the influence and style of the artist and of the artist’s period. d. Studio/Workshop of NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and

Hackett, a work possibly executed under the supervision of the artist. e. School of NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, a work by a follower or student of the artist. f. Manner of NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, a work created in the style, but not necessarily in the period, of the artist. g. After NICHOLAS CHEVALIER: in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, a copy of a work by the artist. h. “signed” / “dated” in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, the work has been signed/dated by the artist. i. “bears signature” / “bears date” in the opinion of Deutscher and Hackett, the work has possibly been signed/dated by someone other than the artist.

PROVENANCE Where appropriate, Deutscher and Hackett will include the known provenance, or history of ownership of lots. Non disclosure may indicate that prior owners are unknown or that the seller wishes to maintain confidentiality.

2. THE AUCTION

Auctions are open to the public and are free to attend. Deutscher and Hackett may exclude any person at any time in its discretion.

REGISTRATION Bidders must register to bid prior to the commencement of an auction. Deutscher and Hackett may impose other obligations on the registration of bidders in its discretion.

CONDUCT OF AUCTION Lots are offered for sale on a consecutive basis. Deutscher and Hackett will determine the conduct of the auction in its absolute discretion, including the regulation of bidding. Consecutive or responsive bids may be placed by the auctioneer on behalf of the vendor up to the reserve.

ABSENTEE OR COMMISSION BIDS AND TELEPHONE BIDS As a courtesy service, Deutscher and Hackett will make reasonable efforts to place bids for prospective buyers in absentia provided written or verbal instructions (as indicated on absentee bid forms included at the back of this catalogue or online) are received 24 hours prior to auction. Where successful, lots will be purchased at the lowest possible bid and in the event of identical absentee bids, the bid received earliest will take precedence. Deutscher and Hackett accepts no responsibility for errors and omissions in relation to this courtesy service and reserves the right to record telephone bids.

RESERVE Unless indicated otherwise, all lots are subject to a confidential reserve price determined by the vendor. Deutscher and Hackett or the auctioneer may place any number of bids on behalf of the vendor below the reserve price and is not obliged to identify that the bids are being placed on behalf of the vendor.

BIDDING INCREMENTS Bidding usually opens below the listed pre-sale estimate and proceeds in the following increments (the auctioneer may vary the bidding increments at his or her discretion): $500 – 1,000 by $50 $1,000 – 2,000 by $100 $2,000 – 3,000 by $200 $3,000 – 5,000 by $200 / $500 / $800 $5,000 – 10,000 by $500 $10,000 – 20,000 by $1,000 $20,000 – 30,000 by $2,000 $30,000 – 50,000 by $2,000 / $5,000 / $8,000 $50,000 – 100,000 by $5,000 $100,000 – 200,000 by $10,000 $200,000 – 300,000 by $20,000 $300,000 – 500,000 by $20,000 / $50,000 / $80,000 $500,000 – 1,000,000 by $50,000 $1,000,000+ by $100,000

SUCCESSFUL BIDS The fall of the auctioneer’s hammer indicates the final bid and the buyer assumes full responsibility for the lot from this time.

UNSOLD LOTS Where a lot is unsold, the auctioneer will announce that the lot is “bought in”, “passed”, “withdrawn” or “returned to owner”.

3. AFTER THE AUCTION

PAYMENTS Payment must be made within seven days of the date of sale in Australian dollars by cash, cheque, direct deposit, approved credit cards or electronic funds transfer. If payment is made by credit card the price will increase by any merchant fees payable by Deutscher and Hackett (1.15% (including GST) for Visa and Mastercard and 1.65% (including GST) for American Express). In certain circumstances, extension of payment may be granted at the discretion of Deutscher and Hackett. Cleared funds will be held in an interest bearing trust account by Deutscher and Hackett until remitted to the vendor. Deutscher and Hackett will be entitled to retain any interest earned during this period. Payment by the vendor of any charge to Deutscher and Hackett is to be made within fourteen days of invoice.

PURCHASE PRICE AND BUYER’S PREMIUM The purchase price will be the sum of the final bid price (including any GST) plus a buyer’s premium set at 25% (inclusive of GST) of the final bid price. Buyers may be liable for other charges reasonably incurred once ownership has passed.

GOODS AND SERVICES TAX Buyers are required to pay a 10% G.S.T which sum is: a. included in the final bid prices where buying from a GST registered vendor; and b. included in any additional fees charged by Deutscher and Hackett; and c. included in the buyer’s premium. Where GST applies to some lots the final bid price will be inclusive of the applicable GST. If a buyer is classified as a “non-resident” for the purpose of GST, the buyer may be able to recover GST paid on the final purchase price if certain conditions are met.

COLLECTION Lots paid for in full may be collected from Deutscher and Hackett premises the day after the auction occurs but lots paid for by cheque may not be collected until all funds have cleared. Proof of identification is required upon collection and lots not collected within seven days of the sale may incur costs associated with external storage and freight.

LOSS OR DAMAGE Risk in the lot, including risk of loss or damage, will pass to the buyer on either the date payment is due, whether or not it has been made, or on collection by the buyer, whichever is earlier. The buyer is therefore encouraged to make arrangements to ensure comprehensive cover is maintained from the payment due date.

TRANSPORT AND SHIPPING Deutscher and Hackett directly offers services including storage, hanging and display, appraisals and valuations, collection management and research and in all instances will endeavour to coordinate or advise upon shipping and handling, insurance, transport, framing and conservation at the request and expense of the client. Deutscher and Hackett does not accept liability for the acts or omissions of contracted third parties.

EXPORT Prospective bidders are advised to enquire about export licences — including endangered species licences and cultural heritage permits, where relevant — prior to bidding at auction. Telephone the Cultural Property and Gifts Section, Museums Section, Ministry for the Arts, on 1800 819 461 for further information. The delay or denial of such a licence will not be grounds for a rescission of sale.

COPYRIGHT The copyright in the images and illustrations contained in this catalogue may be owned by third parties and used under licence by Deutscher and Hackett. As between Deutscher and Hackett and the buyer, Deutscher and Hackett retains all rights in the images and illustrations. Deutscher and Hackett retains copyright in the text contained in this catalogue. The buyer must not reproduce or otherwise use the images, illustrations or text without prior written consent.