74 minute read

important traditional works of art from a private collection, adelaide

from IMPORTANT TRADITIONAL WORKS OF ART FROM A PRIVATE COLLECTION, ADELAIDE+SELECTED AUSTRALIAN FINE ART

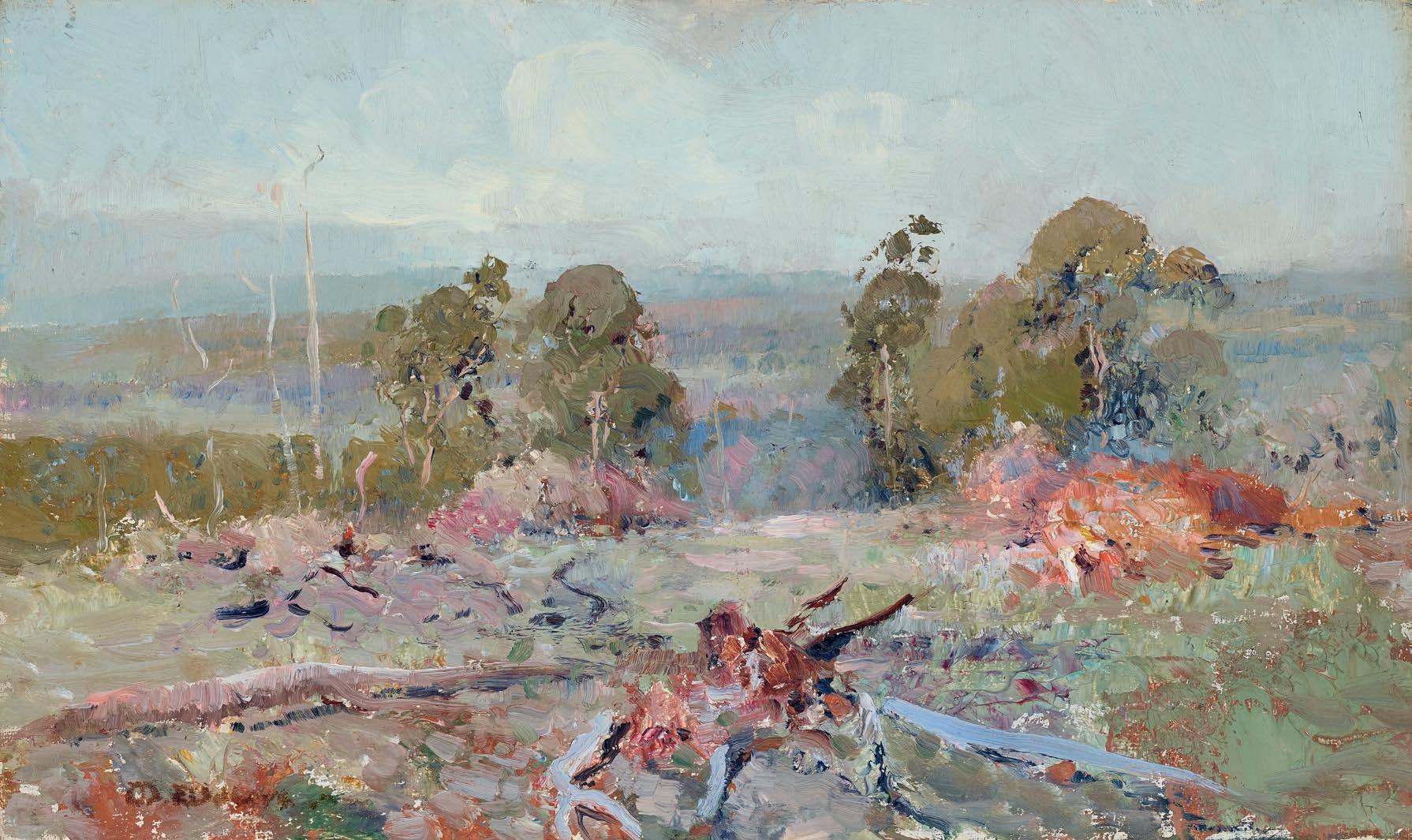

(1855 – 1917) THE CLEARING, MT. MACEDON, c.1904 oil on canvas board 35.5 x 25.5 cm signed lower left: F McCubbin

ESTIMATE: $30,000 – 40,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 80 (label attached verso, as ‘In the Dandenongs’) Three Varied Exhibitions Of Fine Australian Traditional Art, Bugle Galleries, Adelaide, 24 February – 30 March 1976 (as ‘Dandenong Hillside’)

RELATED WORK

The Hillside, Macedon, 1904, oil on canvas, 51.2 x 76.4 cm, private collection, illus. in Clark, J., ‘A Happy Life’: Frederick McCubbin’s Small Paintings & Oil Sketches, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1991, p. 17

When Frederick McCubbin moved to Macedon in 1901 he entered upon, as his son Alexander later wrote, ‘the most fertile and vigorous period of his life.’1 Some of his best and most popular works soon followed including his masterpiece, The Pioneer 1904, ‘an established favorite’ within a short time of its acquisition in 1906 by the National Gallery of Victoria through the Felton Bequest.2 When Childhood Fancies 1905 (private collection) was first exhibited, the art critic for The Age wrote enthusiastically, ‘McCubbin has never painted a more happily inspired picture .’3 And in Lost 1907, (National Gallery of Victoria), another gem from this period, both the narrative and the early morning light filtering through the Macedon bush captured the public’s imagination. McCubbin devoted himself enthusiastically to the subjects around him - ‘The bush up our way looks more charming than ever’, McCubbin wrote to his friend Tom Roberts in 1904. ‘Pictures everywhere.’4 As the gifted interpreter of the secluded glade, he delighted in capturing the play of light in the subtlest of colours, of lyrical moments of childhood and the heroic endeavours of the early settlers of Victoria, the triptych format as much in veneration of the bush itself as of the pioneers.

Significantly, McCubbin named their family Macedon home ‘Fontainebleau’ after the forest in France, neighbouring the village of Barbizon and its school of plein air painters, especially McCubbin’s favourite, Corot. Devoting himself to painting in the open air, he even dug a trench in the ground so that he could reach the canvas tops of The Pioneer. Now in the middle years of his art, his style became broader and vision fresher in response to painting out-of-doors directly from the motif, as readily seen in The Clearing, Mount Macedon, c.1904. The smoothly painted tight style of earlier years gave way to the freer, textured brushstroke and palette knife. These transitions are clearly visible in the comparison of Macedon landscapes such as A Bush Scene 1903, in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat, and two works close to the painting on offer - The Hillside, Macedon 1904, private collection, Melbourne, and Sunny Glade. 5 In these later paintings the brushstrokes are applied with such verve that they seem to dance in spontaneous response to the scene. The focus of attention had now moved from the figure to the enchanting play of light, as in Sylvan Glade, Macedon 1906, in the Bendigo Art Gallery. In radiant sunlight or in shade, each of these paintings captures the characteristic qualities of his beloved bush at Mount Macedon, one of his most fruitful paintings grounds.

1. McCubbin, A., ‘Biographical Sketch of the Life of Frederick McCubbin’, in MacDonald, J.,

The Art of Frederick McCubbin, Lothian, Melbourne, 1916, p. 65 2. ‘Mr. McCubbin’s Exhibition of Pictures’, The Age, Melbourne, 17 May 1907 3. ‘Exhibition of Arts and Crafts’, The Age, 20 November 1905, p. 5 4. Letters to Tom Roberts, vol. II, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney,

A2479, 7 November 1904 5. For The Hillside, Macedon see Clark, J., ‘A Happy Life’: Frederick McCubbin’s Small Paintings & Oil Sketches, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1991, p. 17, p. 12 (illus.), and for Sunny Glade, Sotheby’s, Sydney, 25 August 2002, lot 13

DAVID THOMAS

(1854 – 1914) EARLY MORNING, ELTHAM, 1899 oil on canvas 45.5 x 76.5 cm signed and dated lower right: Walter Withers. / 99 bears inscription with title on label attached to frame verso: Erly [sic.] Morning, Eltham

ESTIMATE: $100,000 – 150,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Melbourne Southern Cross Galleries, Melbourne Private collection, Adelaide, acquired from the above in October 1966 Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Unknown exhibition, lent by the Ladies Art Association, [Ballarat] (label attached verso) Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 123 (label attached verso, as ‘Near Eltham’) In the face of parental opposition to his desired career as an artist, Walter Withers came to Australia from England in 1883 and worked as a jackaroo. Life on the land didn’t last long however, and by the following year he had settled in Melbourne and enrolled at the National Gallery school, extending art studies begun earlier at London’s Royal Academy and South Kensington Schools. There, he met fellow students Louis Abrahams and Frederick McCubbin, as well as the older Tom Roberts – all of whom became lifelong friends – earning the nickname ‘The Orderly Colonel’ as a result of his efficient manner and efforts to organise his colleagues.1

Marrying in England in 1887, Withers and his wife, Fanny, subsequently spent six months in Paris. There, he studied at the Académie Julian alongside many international students including the Australians E. Phillips Fox, Tudor St George Tucker and John Longstaff, who had all flocked to the City of Light, at that time, the centre of the art world. His painting, Life Class, Académie Julian, 1887 – 88 (private collection) describes the life drawing sessions that took place there twice-daily, with models posing at each end of a sky-lit studio, and a large coke stove in the foreground to keep them warm.2 With a commission to produce pen and ink illustrations for a book on early Melbourne, Withers returned to Australia the following year, soon moving to Heidelberg outside Melbourne, where he rented Charterisville, ‘a fine old stone mansion with a large barn and stables … a wild romantic garden … a broken fountain, and an odd pedestal here and there [which] suggested the glory of other days.’3 Cottages in the grounds were sub-let to other artists including Tom Humphrey and Leon (Sonny) Pole, and when, in 1894, the lease was taken over by Phillips Fox and Tucker, who ran a school there offering instruction in plein air painting, it became a popular gathering place for local artists.

Renowned as an artist ‘who went out [in]to nature and made sincere and successful attempts to represent her varying moods’4, Withers’ art was widely recognised during these years. In 1894 the National Gallery of Victoria purchased A Bright Winter’s Morning, 1894 for its permanent collection and Tranquil Winter, 1895, was acquired the following year.5 The Storm, 1896 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) was awarded the inaugural Wynne Prize for landscape painting in 1897 – for which he received a generous payment of £40 – and in 1900 Withers won the prestigious prize again. A measure of international acknowledgement came too, with the inclusion of Tranquil Winter in the colonial art exhibition in London in 1898.

Early Morning, Eltham was painted in 1899 and shows Withers at his characteristic best. Gentle morning light illuminates the expansive scene, broad rolling hills in the distance painted in varying shades of pale blue and green. In the foreground, a lone farmer guides a plough which is being pulled by a pair of horses through a furrowed field, and fine plumes of white smoke rise from a small fire burning to the left, the orange embers and flames the only high-key colour in the composition. Smoke from other fires is visible throughout the scene, a symbol of the quiet labour and routines which brought this otherwise seemingly still landscape to life.

Withers found landscape subjects in many parts of Victoria, travelling by pony and jinker, as well as making use of the expanding rail network to venture further afield. Many of his subjects however, were areas close to his home – especially around Heidelberg and later, Eltham – locations he could walk or cycle to, which he reportedly often did with a prepared canvas and lightweight, portable easel slung over his shoulder.6 Heidelberg was like a small, rural village when Withers lived there during the 1890s, providing many picturesque views which he recorded in oil paint and watercolour. This changed as the city and suburbs grew and in 1903, with funds earned from a major commission to paint a series of narrative panels for Purrumbete (the majestic home of pastoralist W. T. Manifold at Camperdown in the Western District of Victoria), Withers and his family moved to Eltham. Located about twenty kilometres north-east of Melbourne, Eltham offered a country environment and experience, with access to the city via a recently established railway service.

As Fanny Withers wrote, ‘Purchasing a cottage there, with an orchard attached, he built for himself a charming Studio, the windows of which open on to a bit of Virgin Bush, where stand stately white gums of great beauty’.7 Having worked in and around Eltham previously, it was an area Withers knew well, and the decision to live there permanently proved to be productive for his art, offering limitless sources of inspiration: ‘Every form of subject was there before him, with the added charm of rural figures at work in the paddocks, as tending their animals near the homesteads, as following the cows towards the milking sheds; in riding their horses to the creek for water. All these incidents were noted by the painter’.8

1. For Withers’ full biography, see Clark, J., and Whitelaw, B., Golden Summers: Heidelberg and

Beyond, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1985, pp. 28-29 and Andrew Mackenzie,

‘Withers, Walter Herbert (1854-1914)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu/biography/withers-walterherbert-9156/text16183, published first in hardcopy 1990 2. See Taylor, E., ‘The city of light: Australians in Paris’ in Taylor, E., Australian Impressionists in

France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013, pp. 10 and 13 3. Whitelaw, B., ‘Melbourne’s Answer in the 90s – ‘Charterisville’’ in Clark & Whitelaw, op. cit., p. 172 4. ‘Art of Walter Withers’, The Argus, Melbourne, 29 July 1919, p. 6 5. A Bright Winter’s Morning, 1894 was purchased in 1894 and then exchanged with the artist for Tranquil Winter, 1895 the following year. A Bright Winter’s Morning was reacquired for the

NGV collection in 1956 when it was bequeathed by Mrs Nina Sheppard. 6. Mackenzie, A., Walter Withers: The Forgotten Manuscripts, Mannagum Press, Lilydale, 1987, pp. 24 and 30 7. Ibid, p. 27 8. Ibid. p. 130

KIRSTY GRANT

Walter Withers in his studio, Eltham, c.1906 photographer unknown Eltham District Society in partnership with Yarra Plenty Regional Library, Melbourne

WALTER WITHERS

(1854 – 1914) TWICKENHAM RIVER CROSSING, BURNLEY, c.1898 oil on wood panel 16.5 x 25.0 cm signed lower left: Walter / Withers partially inscribed with title on handwritten label attached verso: Twickenham

ESTIMATE: $10,000 – 15,000

11 PROVENANCE

Private collection Theodore Bruce, Adelaide, 18 October 1978, lot 100 Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

RELATED WORK

Twickenham Ferry (Burnley, on the Yarra, Melbourne), c.1905, pencil on paper, 21.0 x 24.0 cm, private collection

WALTER WITHERS

(1854 – 1914) BURNING OFF, c.1894 oil on canvas 30.5 x 51.0 cm signed lower left: W Withers.

ESTIMATE: $20,000 – 30,000

PROVENANCE

Sir Baldwin Spencer, Melbourne (label attached verso) Arthur Tuckett and Son in collaboration with Fine Arts Society Gallery, Melbourne, 19 December 1919, lot 65 Mrs J. S Teulon, Melbourne Mrs Lambert Latham, Sorrento Joshua McClelland Print Room, Melbourne Private collection, Adelaide, acquired from the above 12 June 1978 Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

12 EXHIBITED

Possibly: Annual Exhibition of the Victorian Artists’ Society, Victorian Artists’ Society, Melbourne, October 1894, cat. 80 Sir W. Baldwin Spencer’s Collection, National Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1 December 1916 (label attached verso) The Baldwin Spencer Collection Exhibition, Fine Arts Society Gallery, Melbourne, May 1919, cat. 58

LITERATURE

Possibly: ‘Exhibition of Pictures’, The Age, 25 October 1894, p. 6

(1867 – 1943) SIRIUS COVE, SYDNEY, c.1893 – 95 oil on canvas 36.0 x 28.5 cm signed lower left: A STREETON

ESTIMATE: $180,000 – 260,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Sydney [frame by S.A. Parker] Private collection, Adelaide, acquired prior to 1968 Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Sir Arthur Streeton Exhibition, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 6 – 23 March 1968, cat. 71 (label attached verso, as ‘Sydney Harbour, 1908’) Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 108 (label attached verso, as ‘Sirius Cove’)

‘And then it dipped again, more and more steeply, a shadowy woodland path by this time, showing sudden wide views of the intense blue waters, all overspread with the twinkling dazzle of the reflected sun; and at last it dipped down to the shore, a quiet, lonely, sheltered shore, with a narrow strip of white beach on which little wavelets broke and bubbled, faintly echoing the sound and fury of the ocean surf outside. And here was the camp – a cluster of tents, a little garden, a woodstack, a water tub – almost hidden in the trees and bushes … the camp looked out upon the great gateway of the Heads, and saw all the ships that passed through, voyaging to the distant world and back again. But the ships did not see it.’1

This evocative description of a Sydney harbourside camp featured in Ada Cambridge’s novel, A Marked Man, which was serialised in the Melbourne Age newspaper between 1888 – 89. Arthur Streeton may well have read it there, but by this time, Charles Conder had painted at the camp it describes and his friend and fellow artist, Tom Roberts, had probably visited during a recent trip to Sydney.2 Streeton and Roberts sailed for Sydney together in late 1891, lured by the promise of a rich prize for watercolour landscapes offered by the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, as well as its more enlightened attitude towards collecting Australian art. Committing some of its annual budget to the work of local artists, the Sydney gallery had recently purchased Streeton’s painting, ‘Still glides the stream, and shall forever glide’, 1890.

Although Sydney didn’t suffer from the effects of the economic Depression as badly as its southern neighbour at this time, there were numerous established campsites on the shores of the harbour. Set up in the 1880s as places for weekend recreation, an escape from the ‘foetid air and gritty of the dusty, dirty city’,3 in the following decade they became permanent dwellings for men who couldn’t afford accommodation in town.4 It was at Curlew Camp, located on the eastern shore of Little Sirius Cove – one of numerous bays along the Mosman peninsula on Sydney’s North Shore – where Roberts and Streeton took up residence. Along with the neighbouring Great Sirius Cove, it was named after the flagship of the First Fleet, HMS Sirius, which was careened there in 1789. Part of the traditional lands of the Cammeraigal and Borogeal peoples, it had long been known as Gorma Bullagong.

Accommodation was in canvas tents and a contemporary photograph of the communal artists’ tent shows paper lanterns and lengths of fabric draped from the ceiling, cane and bentwood furniture, ornamental floor rugs, plants and a piano – very much the bohemian gathering place.5 With a freshwater creek nearby, the camp also boasted a cook and an odd-jobs man, and evidently suited Roberts and Streeton well. They lived there, on and off, until April 1896 and January 1897 respectively. Curlew Camp was also home to a varied cast of people during these years, including the artists Julian Ashton, A. J. Daplyn and Albert Henry Fullwood.6 A photograph taken around 1892-93 by Rodney Cherry (a fellow camp resident) of a shirtless Streeton, crouched on the rocky beach at Sirius Cove painting an oil sketch, gives an indication of the simplicity and solitude of camp life. Streeton’s letter to Theodore Fink, written during the summer of 1896, confirms this impression: ‘…Saturday 9pm in our tent at Mossman’s Bay – the front of our tent thrown open wide, & the night sky is deep green blue, & below the great hill the bay reaches down into a deep wonderfull [sic.] gulf, under the sea – picnic parties pulling about quietly through the rare phosphorescence, steamers puffing, breathing heavily & fluting away,

Arthur Streeton at the camp at Mosman, c.1892 – 93 photographer unknown Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney Arthur Streeton From my camp (Sirius Cove), 1896 oil on plywood 28.0 x 21.5 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

& all with me is melody.’7 He wasn’t completely removed from the city however, and as funds allowed, maintained a studio there which was easily accessible via the Mosman ferry which docked beyond the point a short walk from camp.

Streeton was entranced by the ocean, describing it in a letter to Roberts as, ‘a big wonder … a great miracle’, which was ‘hard to comprehend … like death & sleep.’8 It was a central focus of many paintings made during the first half of the 1890s, such as Near Streeton’s Camp at Sirius Cove, 1892 (New England Regional Art Museum) and From my Camp (Sirius Cove), 1896 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) – typically coloured vivid ‘Streeton blue’, sparkling and reflecting the clear blue skies above. In other examples, such as Sirius Cove, c.1895 (National Gallery of Australia) and the current painting, Sirius Cove, Sydney, c.1893-95, the colour is more subdued, as Streeton conveys the sometimes moody atmosphere of the area he had observed so closely and knew so well. In this view, Streeton shares an intimate view of his landscape, looking out across the tranquil waters from Whiting Beach – where Curlew Camp was located – towards Cremorne Point in the distance. The dusky silhouettes of houses and tall buildings lining the horizon remind us that the suburbs and the city are not far away, but it is the peaceful, secluded beach flanked by bush which prevails. The distinctive rocky outcrop of Little Sirius Point in the middle distance leads on to Great Sirius Cove, where a sail boat sits beneath a band of white birds flying above and two figures rowing in a small boat near the shore. In 1900, The Bulletin claimed that it was Streeton, rather than Captain Arthur Phillip, who had discovered Sydney Harbour.9 His myriad paintings of the subject, even then, well-known and loved, had already become iconic depictions of what Mark Twain, upon visiting in 1895, described as ‘the darling of Sydney and the wonder of the world … beautiful – superbly beautiful’.10 Streeton’s singular vision of the harbour and surrounding landscape captured its light, movement and colour, eschewing the realism of other depictions,11 and conveying its distinctive atmosphere in a manner that makes these images as appealing today as they were at the time they were painted.

1. Cambridge, A., A Marked Man, Sydney, 1987, chap. 24, p. 163 quoted in Eagle, M., ‘Streeton in the City of Laughing Loveliness’, Lane, T., Australian Impressionism, National Gallery of

Victoria, Melbourne, 2007, p. 201. First published in London in 1891, this was serialised in the Age between 1888-89 under the title, The Black Sheep. 2. Eagle, ibid. 3. Thomas, A., Bohemians in the Bush: The Artists’ Camps of Mosman, Art Gallery of New South

Wales, Sydney, 1991, p. 31 4. See Topliss, H., The Artists’ Camps: Plein Air Painting in Australia, Hedley Australia

Publications, Melbourne, 1992, p. 134; Thomas, ibid.; and Eagle, M., The Oil Paintings of

Arthur Streeton in the NGA, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1994, p. 61 5. Topliss, ibid., p. 135 6. Eagle, 1994, op. cit. 7. Streeton to Theodore Fink, c. January 1896, quoted in Galbally, A. and Gray, A., Letters from

Smike: The Letters of Arthur Streeton 1890-1943, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989, p. 66 8. Streeton to Tom Roberts, quoted in Eagle, 2007, op. cit., p. 207 9. See Mimmocchi, D., ‘An Artist’s City: Streeton in Sydney’ in Tunnicliffe, W., Streeton, Art

Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2020, p. 96 10. Twain, M., Following the Equator: A Journey around the World, Hartford, Connecticut, 1897, chap. 9, p. 57 quoted in Eagle, 2007, op. cit., p. 204 11. Eagle, ibid.

KIRSTY GRANT

(1856 – 1931) KIRRIBILLI POINT, SYDNEY, c.1895 oil on wood panel 18.0 x 25.5 cm

ESTIMATE: $80,000 – 120,000

PROVENANCE

Mr H. L Johnstone Leonard Joel, Melbourne, 7 March 1969, lot 26 (as ‘Sydney Harbour, c.1880’) Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 98 (as ‘Summer’)

LITERATURE

Spate, V., Tom Roberts, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1978, cat. 86 Topliss, H., Tom Roberts: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. I, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985, cat. 284, vol. II, pl. 128 (as ‘Untitled, Kirribilli Point’, c.1890 – 98) Hailed as the father of Australian landscape painting, Tom Roberts holds a significant place in the history of Australian art. With Fred McCubbin and Louis Abrahams, he established the first painting camp at Box Hill in the summer of 1885, cementing the local practice of plein air painting with naturalistic images which celebrated the ‘wild bush, tall young saplings with the sun glistening on their leaves’.1 Four years later, Roberts was the instigator of the famous 9x5 Impression Exhibition held at Buxton’s Rooms in Melbourne, where 183 small paintings – many on cigar box lids – declared that quick, painterly impressions emphasising fleeting atmospheric effects were the artistic order of the day.

Roberts is perhaps best known, however, for his large and consciously nationalistic pictures which have become iconic depictions of life in Australia including Shearing the Rams, 1888-90 (National Gallery of Victoria) and A Break Away!, 1891 (Art Gallery of South Australia). Painted during the late nineteenth century, in the years leading up to the Federation of Australia, these pictures remain on permanent display in the public galleries that house them, markers of national identity centred on rural life and activity, which still have relevance despite Australia’s urbanisation and the fact that most of the population resides in cities along the coastal periphery.

Although Roberts and his fellow members of the so-called Heidelberg School are strongly associated with the rural Australian landscape, they lived predominantly urban lives and were at home in close proximity to the city. Bush scenes were painted during camps and on excursions made possible by the extension of the railway network around Melbourne. Later, Roberts travelled widely, seeking varied subjects for his work, but he also consistently maintained city-based studios. In Melbourne for example, he was at 95 Collins Street in 1885 – where he probably began work on the view of Melbourne’s bustling centre, Allegro con brio, Bourke Street west, c.1885-86, reworked 1890 (National Gallery of Australia and the National Library of Australia) – then the St James Building, 59 William Street (1887) and from 1888, a residential studio on the top floor of Collins Street’s new Grosvenor Chambers. A member of the Buonarotti Club, as well as a founding member of both the Australian Artists’ Association and the Victorian Artists’ Society, Roberts was actively involved in Melbourne’s artistic community during these years. He also understood the importance of cultivating the

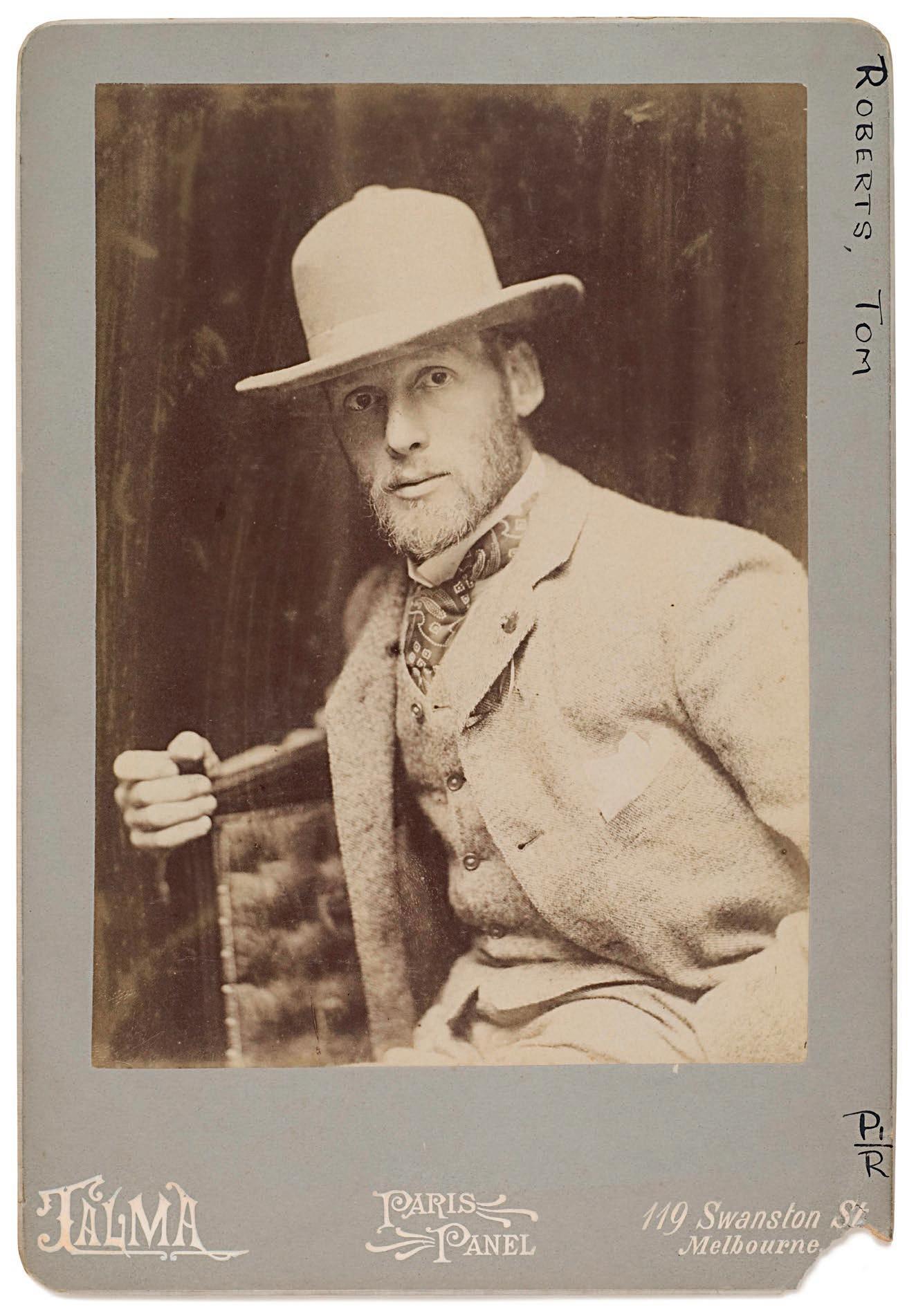

Tom Roberts, c.1895 photographer: Talma Studio, Melbourne State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Tom Roberts Sydney Harbour from Milson’s Point, 1897 oil on wood 18.3 x 33.0 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

audience for his work, and the critical need for enthusiastic patrons, opening his studio for previews and socialising with the right people. To this end, he was successful, as the range of sitters who feature in his extensive portrait oeuvre attests.

Visiting Sydney for several weeks in March-April 1888, Roberts met the young Charles Conder and working side by side, the two artists famously painted views of Coogee Bay from the same vantage point.2 Roberts’ Holiday Sketch at Coogee, 1888 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) reflects his delight in the beauty of the scene and the intensity of Sydney’s light and colour. The vibrant blue of the ocean is a central focus. Other seascapes from the time were ‘executed with unprecedented boldness … Roberts was not so much depicting the objective being of the landscape, as expressing his subjective reaction to it. He translated his external delight into sensuously handled paint.’3

The chromatic brilliance of harbourside Sydney is also a primary focus of this view. A study of sea and sky, the picture is divided into two broad horizontal bands, the pale blue of the sky, broken up with occasional white clouds, reflected in the vivid blue of the calm water below. Helen Topliss has identified the area seen across the open water as Kirribilli Point, and the distinctive multi-storey building on the left hand side appears to be the Pastoral Finance Association Wool Store, which was constructed in 1892 adjacent to the grounds of Admiralty House, the long roof of which can be seen to the right.4 The seven storey PFA warehouse was reportedly ‘one of the most conspicuous [buildings] on the harbour front’5 and when it burned down in December 1921 along with the 30,000 bales of wool it housed, provided ‘a magnificent spectacle … for the thousands of ferry passengers … who watched the devastating progress of the fire’.6 The industry that characterised much of harbourside Sydney during the late nineteenth century is highlighted by the nearby tug boat, a short white wake describing its slow and steady path. The most prominent man-made element of the scene is the elegant four-masted schooner to the right, which directs the view into the distance beyond Kirribilli Point towards Bradleys Head, with Fort Denison visible in between. Topliss highlights the variety in Roberts’ painting technique, pointing out that the lines on the side of the vessel are incised with the end of a paint brush.7 The textured sky too, exemplifies his lively brushwork.

Roberts had been resident in Sydney since 1891, when he arrived from Melbourne by ship with Arthur Streeton, and took up residence at Curlew Camp on Little Sirius Cove. Living at the beachside campsite on and off until his marriage five years later, Roberts had constant access to the water and Kirribilli Point, thought to have been painted during the mid-1890s, reflects his intimate knowledge of the myriad moods and colours of the harbour.

1. Nancy Elmhurst Goode quoted in Whitelaw, B., ‘’Plein Air’ Painting: The Early Artists’ Camps

Around Melbourne’ in Clark, J. and Whitelaw, B., Golden Summers: Heidelberg and Beyond,

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1985, p. 55 2. Tom Roberts, Holiday Sketch at Coogee, 1888 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and Charles

Conder, Coogee Bay, 1888 (National Gallery of Victoria). See Eagle, M., ‘Friendly Rivalry:

Paintings of Waterside Sydney, 1888 and 1890’ in Lane, T., Australian Impressionism,

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2007, pp. 103 – 108 3. Spate, V., Tom Roberts, Lansdowne Editions, East Melbourne, 1978, p. 52 4. Topliss, H., Tom Roberts 1856-1931: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 1, Oxford University Press,

Melbourne, 1985, cat. 284, p. 152. Topliss notes ‘the building on the left is Dalgetty’s [sic.] woolshed, which burned down in 1926’, however research suggests that the wool store was owned by the Pastoral Finance Association and burned down in 1921. See ‘The Leading Wool

Selling Houses of Sydney’, The Sydney Wool and Stock Journal, 9 May 1902, p. 7; ‘The Great Sydney Fire: Destruction of the P.F.A. Stores’, Sydney Mail, 21

December 1921, p. 5 and ‘Kirribilli’s Great Fire’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 May 1954, p. 7. 5. Sydney Mail, ibid. 6. Ibid. 7. Topliss, vol. 1, op. cit., p. 152

KIRSTY GRANT

(1867 – 1943) SUNLIGHT AFTER RAIN, 1938 oil on canvas 76.5 x 64.0 cm signed lower left: A STREETON dated lower right: 1938 bears inscription on stretcher verso: 6

ESTIMATE: $150,000 – 200,000

PROVENANCE

Estate of Mrs. M. Levinson, Adelaide Theodore Bruce, Adelaide, 11 November 1962, lot 92 (as ‘In the Park’) Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Arthur Streeton’s Exhibition: Form and Colour, Athenaeum Gallery, Melbourne, August 1938, cat. 6 Three varied exhibitions of Fine Australian Traditional Art, Bugle Galleries, Adelaide, 24 February – 30 March 1976 (as ‘In the Park’)

LITERATURE

‘Paintings by Sir A. Streeton’, The Age, Melbourne, 2 August 1938, p. 6 ‘S.A. Auction’, The Advertiser, Sydney, 15 November 1962 (as ‘In the Park’)

Even as a young man in his twenties, Arthur Streeton longed for a garden of his own, writing to Tom Roberts in 1892 about the home of a patron, ‘Peach trees in blushing bloom …scarlet poppies bending to the rich grass, & bright sweet nasturtiums & mignonette & violets, ay’ and roses, all blooming around a pretty house… Yes, I must have a pastoral treasury like this some day’.1

The first steps towards making this desire a reality took place during the 1920s, by which time Streeton was widely celebrated as one of Australia’s finest painters. In 1921, he purchased five acres of land at Olinda in the Dandenong Ranges east of Melbourne, naming it ‘Longacres’. Following the sale of Golden Summer, Eaglemont, 1889 (National Gallery of Australia) for the extraordinary sum of 1000 guineas, he built a house there several years later and enthusiastically began to develop a garden against the backdrop of established native blackwoods and gum trees. In 1927, Streeton bought a house on the corner of Grange Road and Douglas Street in Toorak, later purchasing the neighbouring property in order to extend the garden. He typically spent summers at Olinda, as well as making regular visits during the year, a pattern which he maintained throughout the following decade until moving there permanently in 1939. Writing to Julian Ashton in July 1934, Streeton joked, ‘I am beginning to find that painting nowadays is beginning to interfere seriously with my gardening operations.’2 Indeed, the strength of his horticultural passion was made very clear in an article he penned earlier that year for the Melbourne Argus: ‘Gardening, once it attains a firm hold upon a man, enslaves him just as does alcohol or a pernicious drug; but the aftereffects are entirely different. Doing one’s own gardening, like painting pictures, has its own reward – the secret pleasures of doing it… It is one of the advantages of a civilised state to labour from morning till night in one’s half-acre garden with the freedom to do things in one’s own way.’3

It is not surprising then, that views of domesticated landscapes – including his own gardens – feature in Streeton’s oeuvre, and many of the still life paintings produced later in his career depict flowers which he had tended and grown. Sunlight After Rain, 1938, which is possibly a view of the garden at ‘Longacres’, where apple trees still grow, depicts two tall trees enclosed in an intimate space with a dense band of trees beyond. Reflecting the artist’s familiarity with his subject, as well as his sensual response to its natural beauty, the image is infused with light, the ubiquitous ‘blue and gold’ so well-known from his earlier landscapes, combined with the depiction of the varied textures and colours of foliage. Streeton received major accolades during the 1930s: he was the subject of a retrospective at the National Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1931, and received a knighthood in 1937. These career highlights were counterbalanced in 1938 with the death of Nora, his wife of thirty years. Looking for meaning beyond the literal, it is tempting to interpret this painting as an image of quiet optimism, acknowledging his sadness, but looking forward to the possibilities of the future.

1. Streeton to Tom Roberts, Melbourne, 29 June 1892 quoted in Smith, G., and Streeton,

O., Arthur Streeton: The Passionate Gardener, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery,

Mornington, 2001, p. 7 2. Streeton to Julian Ashton, Melbourne, 4 July 1934 quoted in Smith and Streeton, op. cit., p. 12 3. Streeton, A., ‘On Gardening – A Reverie’, Argus, Melbourne, 6 January 1934, p. 4

KIRSTY GRANT

(1873 – 1930) ARTIST AND HIS BATMAN, LIGHT HORSE CALVARY, JERUSALEM HEIGHTS, 1920 oil on canvas on plywood 31.5 x 42.0 cm signed with initials lower right: G. W. L

ESTIMATE: $100,000 – 150,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection Sir Edward Hayward, Adelaide Old Clarendon Gallery, Adelaide (label attached verso) Private collection, Adelaide, acquired from the above in November 1982 Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Royal Visit Loan Exhibition of Australian Paintings, National Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 1954 (label attached verso) Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 66 (label attached verso, as ‘Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Height’) George Washington Lambert, S.H Ervin Museum and Art Gallery, The National Trust of Australia, Sydney, 22 August – 8 October 1978, cat. 41 (as ‘Australian Light Horse on the hills above Damascus’) Old Clarendon Gallery, Adelaide, 1982 (as ‘Portrait with Horses’)

LITERATURE

Gray, A., George Lambert 1873–1930: Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculpture, Drawings in Public Collections, Bonamy Press, Perth, Sotheby’s Australia and Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1996, cat. P356, p. 95 (as ‘The artist and his batman’)

RELATED WORK

The official artist (Self Portrait), 1921, oil on canvas, 91.7 x 71.5 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra When the First World War erupted, George Washington Lambert was aged forty and resident in Britain. A society painter of some renown, his equestrian portrait of Edward VII (1910) was considered by many as the best ever done of the monarch. Now considered an equal in London’s art world, Lambert had actually spent his formative years working on a sheep property at Warren in far-western New South Wales and remained in his heart a ‘country man’ with a great love of horses and abiding respect for people who worked the land. In late 1917, he was commissioned to be Australia’s sole war artist in Palestine, and through this ‘the war was to release the man of action that slumbered in Lambert. Always a keen observer, he was by this a splendidly trained draughtsman capable of painting equally well men, horses and landscape, and the incidents of war – the ideal man for Palestine.’1 Artist and his batman, Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Heights, 1920, is a self-portrait as personal souvenir, one redolent of his experience embedded with the troops.

Due to his age, Lambert was unable to enlist for the Australian Imperial Force, so he joined a voluntary unit called the United Arts Rifles, where he trained recruits in horsemanship. Following the appointment as war artist, he travelled to Palestine where the Light Horse Brigade was engaged in fighting the Turkish forces. On Christmas Day, ‘complete with a Light Horseman’s plumed hat, spurs, leggings and honorary commission as Lieutenant’, Lambert sailed for the Palestine front and disembarked in Alexandria three weeks later.4 The artist was dazzled by the blazing light which played over the jagged landscape, and soon recognised in the ‘“sweating, sun-bronzed men and beautiful horses” of the Light Horse, the pioneer bushmen he had observed working the wool trade (on) his uncle’s property at Warren.’5 Many of Lambert’s new companions were veterans of the Gallipoli campaign, and with their guidance and vivid stories, he moved from Egypt through to Syria and Palestine, producing forty-nine oil sketches and nearly a hundred drawings, as well as several sketchbooks filled with small pencil studies by the end of the three-month commission.

Captain George W Lambert, official war artist, standing with a Turkish pony, 1919 photographer: George Hubert Wilkins. One of a series of photographs taken on the Gallipoli Peninsula under the direction of Captain C E W Bean of the Australian Historical Mission, during the months of February and March, 1919. Australian War Memorial, Canberra

In early 1919, Lambert was the only artist invited to join the historian Charles. E. W. Bean on the first official mission to visit Gallipoli since the ANZAC forces had evacuated. He again produced many images but also revealed his strength of character when he and others of the party were ‘forced to bury more than 300 bodies in a strip of land the size of three tennis courts [at The Nek], which prompted Lambert to write to his wife that “gruesome is scattered all over the battlefield... evidence grins coldly at us non-combatants and I feel thankful that I have been trained to stop my emotions at the border line.’’’6 He then re-visited Palestine and Syria, painting more preparatory studies as he again stayed with the Light Horse whilst they demobilised. On return to London, Lambert set to work creating large paintings based on his sketches, armed with new understanding of the true horrors of war. Numerous of these are now star attractions at the Australian War Memorial, such as The charge of the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba 1917, 1920; ANZAC, the landing 1915, 1920-22; and The charge of the 3 rd Light Horse Brigade at the Nek, 7 August 1915, 1924. However, it is in the smaller, more intimate works painted at the same time that Lambert truly expressed himself, celebrating the camaraderie experienced amongst his fellow horsemen. Artist and his batman, Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Heights is one of these and its sense of immediacy is striking. Jerusalem is set on a plateau 785 metres above

Captain George W Lambert, Official Artist, sketching. An unidentified soldier is standing watching him, c.1918 Photographer: Oswald Hillam Coulson Australian War Memorial, Canberra George W. Lambert A sergeant of the Light Horse, 1920 oil on canvas 77.0 × 62.0 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

sea level, with views overlooking the Dead Sea, the biblical Mountains of Moab, and coastal plains that march west toward the Mediterranean. It was territory Lambert knew intimately, having ‘camped for a time during the fierce heat of the summer of 1918 in Chauvel’s Desert Mounted Corps camp at Talaat ed Dum [just north of Jerusalem], in the hideous country of the Wilderness, and from there, and from the Light Horse camps down in the stifling Jordan Valley, he would walk out day after day for hours at his labour of love.’7 In this self-portrait, painted in the London studio, Lambert’s delight is obvious, seated with his portable paint box in this harsh land amongst the horses and men he so admired, his smiling face and favourite pipe accentuated by the curved loop of the white bridle. His batman, who has not been identified, wears the Light Horse emblem of an emu feather in his hat and was an essential companion in Palestine, being a soldier assigned to act as a servant to commissioned officers and who also looked after their horse (known as the bat-horse).8

Lambert returned to Australia in 1921 and was to enjoy another decade of success in Australia and Britain, but his experiences in the Middle East remained some of his happiest memories. He actively re-engaged with the Australian art community and was important in his advocacy and support for a number of younger artists. Horses, however, remained his greatest love and it was after a ride in May, 1930, as he leant over to fix a piece of timber to his mount’s drinking trough, that this grand cavalier died of a heart attack. Arthur Streeton was devastated to lose his old friend, writing to Basil Burdett that ‘it’s difficult to get the horrible news out of one’s head – it’s quite useless to fret about him. But everything here reminds me of him ... poor old Julian Ashton will feel it, he was always so proud of G. W. L.’9

1. Lindsay, L., ‘George Lambert – our first Australian master’, Art in Australia, 3rd series, no.36,

February 1931, p. 15 2. Konody, P.G., The Observer, London, 5 June 1910 3. See Motion, A, The Lamberts: George, Constance and Kit, Chatto and Windus, London, 1886, p.45 4. Roberts, Major M. L. H., ‘George Washington Lambert’, The Australian Light Horse Association, www.lighthorse.org.au/george-washington-lambert Viewed 12 October 2021 5. Yip, A., ‘George Lambert at Gallipoli. ‘A wonderful setting for the tragedy’: an artist captures the Anzac horror’, Look magazine, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2013, pp. 10-11 6. Ibid. 7. Gullett, H.S., ‘Lambert and the Light Horse’, in: Art in Australia, ‘Lambert Memorial Number’, 3rd series, no.33, August-September 1930 8. Charles Bean recorded that Lambert was assigned a Light Horseman named (William?)

Spruce from Port Stephens, NSW, to handle the mule the artist used to carry his supplies in

Gallipoli, but there is no record that Spruce was also with Lambert in Palestine. The author thanks Hollie Gill at the Australian War Memorial for this information. 9. Arthur Streeton, letter to Basil Burdett, 31 May 1930. Transcribed in: Galbally, A., and Gray,

A., Letters from Smike: the letters of Arthur Streeton 1890-1943, Oxford University Press,

Melbourne, 1989, p. 196. Between 1895 and 1899, Lambert studied with Julian Ashton who always remained proud of student’s achievements.

ANDREW GAYNOR

(1873 – 1930) EYRE AND WYLIE, 1908 oil on wood panel 26.5 x 38.0 cm signed lower right: G. W. LAMBERT bears inscription on handwritten label attached verso: ‘Eyre the Explorer threatened by blacks who had murdered Baxter, Wylie (the aborigine) saved Eyre’s life’

ESTIMATE: $50,000 – 80,000

PROVENANCE

Mrs. L. Abrahams, Melbourne, by 1918 George Page Cooper, Melbourne The Historical George Page Cooper Collection, Leonard Joel, Melbourne, 21 November 1967, lot 354 Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Loan Exhibition of Australian Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, April 1918, cat. 71 (as ‘Eyre the Explorer’) Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 69 (label attached verso) George Washington Lambert, S.H Ervin Museum and Art Gallery, The National Trust of Australia, Sydney, 22 August – 8 October 1978, cat. 8

LITERATURE

Lang, W. H., Romance of Empire: Australia, T.C. & E.C. Jack, London, 1908, p. 164 (illus., as ‘Eyre and Wylie threatened by the murderers of Baxter’) Borlase, N., ‘A love of flamboyance’, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 September 1978, p. 17 Gray, A., George Lambert 1873–1930: Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculpture, Drawings in Public Collections, Bonamy Press, Perth, Sotheby’s Australia and Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1996, cat. P88, p. 25

RELATED WORK

Burke and Wills on the way to Mount Hopeless, 1907, watercolour, 26.2 x 38.5 cm, in the collection of Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria An historical incident (a little white hero), 1907, pencil, watercolour and gouache, 30.5 x 41.9 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Kate Kelly (during the last stand of the Kelly Gang), 1908, oil on canvas, 36.5 x 51.0 cm, private collection

Samuel Calvert Eyre’s Journey to Albany, 1891 wood engraving State Library of Victoria, Melbourne

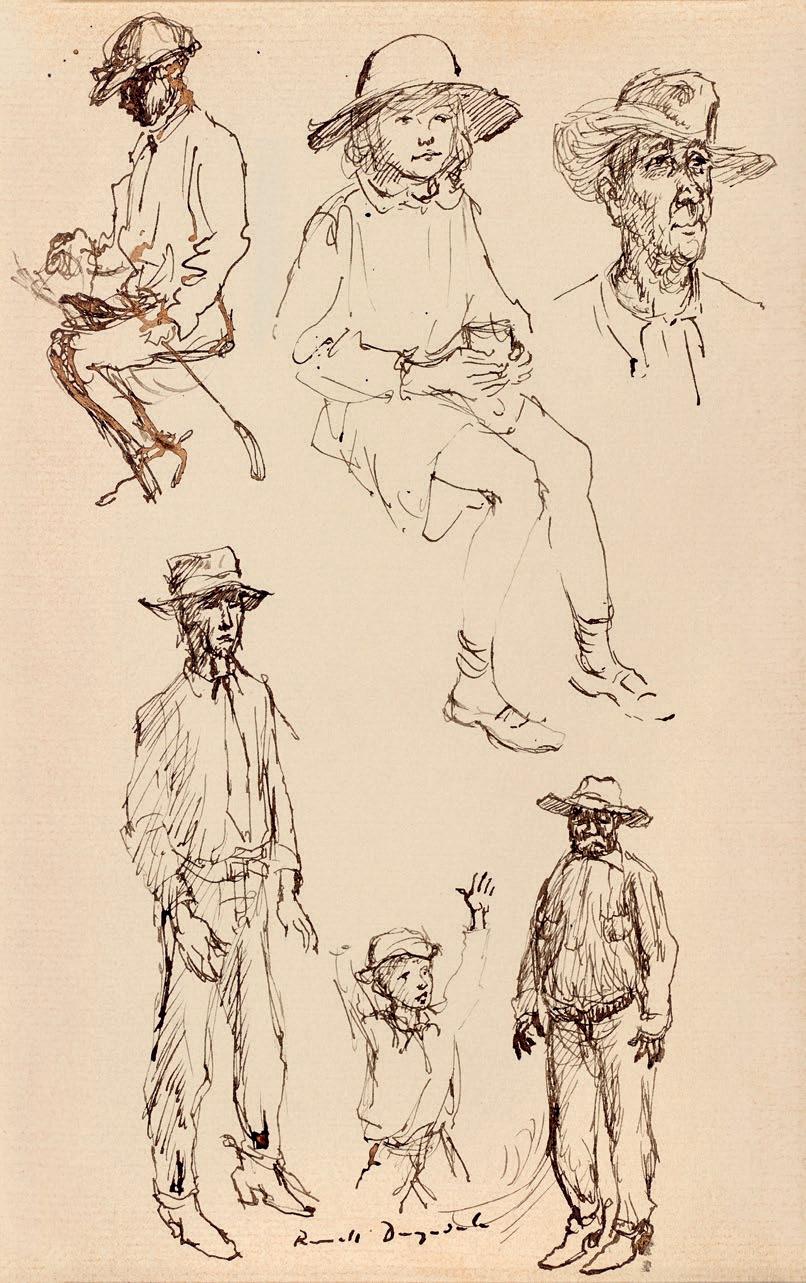

The epic saga of Edward Eyre and Wylie’s arduous crossing of the Nullarbor Plain in 1841 is almost operatic in its dimension. The two young men experienced tragedy, starvation, deprivation and drought, yet both made it alive to King George’s Sound in Western Australia having stumbled overland for nearly 600 miles (965 kilometres) from their start in South Australia. When W. D. Lang’s Romance of Empire: Australia was being planned in 1907, it was to be the first national history written for child readers; thus, it was a certainty that Eyre and Wylie would be included in the narrative. However, the editorial choice of George Lambert to provide illustrations was particularly inspired and ensured that an artist who loved the Australian outback, its people and its horses would be responsible for visualising many of the book’s exciting ‘Boys Own’ moments. Confrontation, Eyre and Wylie, 1908, captures a pivotal moment two months after departure when the explorers’ overseer was shot by two of the party’s younger members, who then abandoned Eyre and Wylie to their fate; and Lambert’s crisp draughtsmanship is on full display.

When commissioned to work with Lang, the artist was already noted for his illustrations for The Bulletin from 1895, and for similar work in three books published by Angus and Robertson. After re-locating to London in 1902, he continued the practice with Cassell’s and Pall Mall magazines, and the following year, drew lively sketches for Alexander Wilberforce (A. W.) Jose’s Two awheel: and some others afoot in Australia. However, Jose’s writing suffered next to Lambert’s contributions with The Bulletin for one proclaiming that ‘the illustrations are more interesting than the book.’1 In 1907, he was invited to create twelve images to accompany the text in Romance of Empire: Australia, one in a new series of books exploring outposts of the British Commonwealth; other countries included Canada, India, West Africa, New Zealand and South Africa. Lambert’s illustrations were originally executed in watercolour and he chose to subsequently reproduce a small number of these in oils, including the lot on offer here.

The description of Eyre and Wylie’s journey covers three chapters in Romance of Empire: Australia and was informed by the author reading Eyre’s own account, published in 1845, and Professor J.W. Gregory’s The dead heart of Australia: a journey around Lake Eyre in the summer of 1901-1902, which appeared in 1906.2 In 1840, Eyre was still only twenty-five, yet had already gained notable attention for his entrepreneurship in driving stock from Sydney to South Australia, plus a sequence of explorations to the north of Adelaide. In January 1841,

Edward John Eyre, c.1860 photographer unknown State Library of South Australia, Adelaide

he commenced the attempt to cross the Nullarbor, and after a few stalled beginnings, Eyre sent most of the party back once they reached the head of the Great Australian Bight. His remaining companions were the overseer John Baxter; Wylie, a sixteen year-old Noongar man from the King George Sound district; and two younger boys, Neramberein and Cootachah, recorded as being from the Flinders Ranges.3

By mid-April, privations had set in sowing discontent, and on 29 April, disaster struck. Eyre had taken the first turn in watching the horses that night ‘and as it drew eleven he peered through the scrub to catch the glow of the camp fire, for Baxter’s watch began at that hour. Then suddenly, about a quarter of a mile away, there was a flash and the loud report of a gun.’4 Baxter was dead, shot by Neramberein or Cootachah who had apparently been disturbed by the overseer when they tried to steal supplies. Wylie chose to stay with Eyre in spite of repeated attempts over the next days by his former companions to entice him to join them; the two boys subsequently vanished.

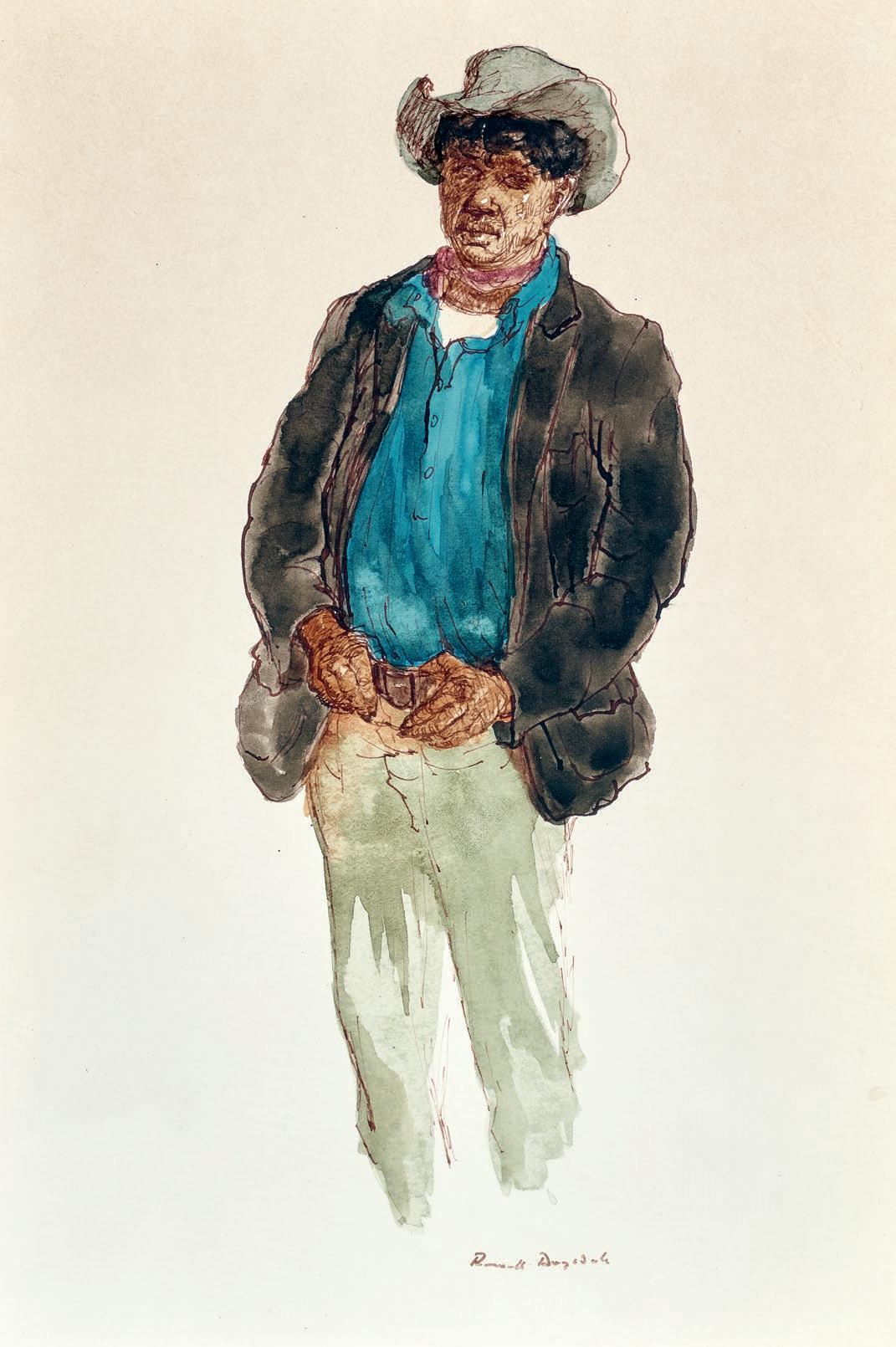

Lambert’s painting shows Eyre being menaced by the killers as Wylie cowers in his wake, an exaggerated stereotype rife in the Edwardian age. Even so, the artist has captured the high drama of the confrontation and vividly displays the physical privations endured by all the participants, horses included. Lambert has reduced the palette dramatically to monochromatic brown and grey reinforcing its emotive suggestion of a desperate moment in a desolate place. After many more struggles, the two men reached Albany where Wylie was greeted ecstatically by his people, who had believed him already dead. Of the twelve gouache and watercolour images which appeared in Romance of Empire: Australia, two are in the collections of the Bendigo Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria. The two that Lambert chose to re-imagine in oil paint were Eyre and Wylie and another of Ned Kelly’s sister Kate appealing to police at Glenrowan, location unknown.

1. ‘The red page: newly published’, The Bulletin, vol. 24, no. 1240, 19 November 1903, inside front cover, np 2. See Lang, W. H., Romance of Empire: Australia, T.C. & E.C. Jack, London, 1908, p. 148 3. Also known as Yarry and Joey, the two boys were probably of the Adnyamathanha people, and both had already been in Eyre’s employ for some years. 4. Eyre, E. J., Journals of expeditions of discovery into central Australia and overland from

Adelaide to King George’s Sound in the years 1840-1, T. and W. Boone, London, 1845, vol 2, (online), www.gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00048.html Viewed 12 October 2021

ANDREW GAYNOR

(1873 – 1930) PORTRAIT OF THEA PROCTOR, 1905 oil on canvas 51.0 x 41.0 cm signed and dated lower right: G. W LAMBERT / 1905

ESTIMATE: $30,000 – 40,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection Theodore Bruce, Adelaide, 30 July 1970 Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 67 or 70 George Washington Lambert, S.H Ervin Museum and Art Gallery, The National Trust of Australia, Sydney, 22 August – 8 October 1978, cat. 13

RELATED WORK

Miss Thea Proctor, 1903, oil on canvas, 90.0 x 69.8 cm, in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

George Lambert and Althea (Thea) Proctor were students together in the late 1890s at the painting academy run by Julian Ashton, later renamed the Sydney Art School. In 1900, Lambert was awarded the inaugural Society of Artists’ Travelling Scholarship and left for England with his wife Amy, whom he had married two days earlier. In 1903, Proctor also arrived in London and to assist her finances, worked parttime as a paid model for Lambert Through this she become an integral component in a sequence of portraits that established her colleague’s European reputation as a painter of note, and Portrait of Thea Proctor, 1905, is a fine example of their collaboration.

Proctor was acknowledged as one of the most stylish Australian women of her time. She combined charm and elegance with a renowned talent for art and design, particularly woodcuts, of which The rose, c.1928, and Women with fans, c.1930, are readily identifiable images from this country’s artistic heritage. In the lead up to leaving for London, Proctor had been engaged for some years to fellow art student Sydney Long, who shared one of the Ashton school’s studios with Lambert. Frustrated by Long’s reticence to commit, she returned the ring and left for overseas. Conversely, her connection to Lambert in London developed well beyond her role as model and she became, above all, his vibrant and intelligent art colleague; a confidant and muse, but not his lover as conjecture has often suggested. In fact, she became an extended member of the artist’s family, ‘a woman with whom Lambert could visit an exhibition while Amy stayed at home and looked after the children, and who in turn was willing to mind the children while he and Amy went to concerts or the theatre.’1 Their first success was the commanding Miss Thea Proctor, 1903, which so impressed the judges at the Royal Academy that it was ‘hung on the line’ at their annual exhibition. Proctor is depicted in this work as both sophisticated and aware, brimming with a forthright confidence that Lambert captured perfectly.

In 1905, he painted Althea, a full-length portrait of Proctor wearing a high-necked black dress and striding across the moors with a greyhound.2 She is shown without a hat but the tilt of the head is identical to the painting on offer here, hinting that Portrait of Thea Proctor may well be a related work, with the main difference being that she is now crowned by a fashionably wide-rimmed and feathered hat, worn at a rakish, suggestive angle. Lambert’s bravura technique as a painter exudes from the frame, with the sweep of the feather carried through by the curves of Proctor’s neckline and the decorative black ribbon attached to the hat. A cameo of rich red and gold sits at her sternum, the colour of which assists to accentuate the sitter’s rich, auburn hair and sensual red lips. There are a number of major works by Lambert featuring Proctor and all but two are now owned by Australian State galleries. Of the latter, the prominent collector Kerry Stokes owns The blue hat, 1909; and Portrait of Thea Proctor, 1905, is the only example remaining in private hands.3

1. Gray, A., George Lambert retrospective: heroes and icons, National Gallery of Australia,

Canberra, 2007, p. 17 2. Althea was subsequently cut down in size and has been re-titled Portrait of Thea Proctor by the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. 3. A final portrait of Proctor, location unknown, is illustrated in Jose, A. and others, The art of

George W. Lambert A.R.A, Art in Australia, Sydney, 1924, pl. 46

ANDREW GAYNOR

(1768 – 1851, British) SELF PORTRAIT, 1835 oil on canvas 95.5 x 82.5 cm signed with initials and dated lower right: B D. 1835

ESTIMATE: $100,000 – 150,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Hobart (acquired directly from the artist in payment of an account – the first owners were said to be early Hobart bakers) Thence by descent Ted Braithwaite, Esq. Christie’s, Sydney, 1 October 1974, lot 10 Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

LITERATURE

Buscombe, E., Artists in Early Australia and Their Portraits, Eureka Research, Sydney, 1979, no. 28/1a P., pp. 320.1 (illus.), 321

RELATED WORKS

Portrait of an Artist (Self Portrait) c.1819, oil on canvas, 76.7 x 64.2 cm, private collection Self Portrait, 1837, oil on canvas on composition board, 91.5 x 72.0 cm, presented by Mr L Lodge, 1900, AG140, in the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart This celebrated picture, called the School of Athens, which is at Oxford University, where I have spent much time in studying it and examining every minute part, was painted by Julio Romano from the original picture in the Vatican at Rome, which was painted by Rafaelle.

The more I bring this grand work to my mind, the more it appears to be a subject that should be spoken of in this room, where we consider that the School of Hobart Town [The Mechanics’ Institution] was instituted to disseminate useful knowledge, and in that point of view closely resembles the School of Athens.

BENJAMIN DUTERRAU, HOBART TOWN, 1849.1

Born into an old Huguenot family as the son of a watchmaker, Londonborn widower Benjamin Duterrau was one of the steerage passengers on board the ship Lang that arrived safely in the harbour of Hobart Town in the evening of 16 August 1832, having sailed direct from the heart of the British Empire to its furthest outpost.2

The so-called Black War – the conflict between European settlers and the Tasmanian Aboriginal (Palawa) people – had all but ceased by the time of Duterrau’s arrival, the historic conciliation that took place on 31 December 1831 signalling the end of physical hostilities between the colonisers and the island’s indigenous inhabitants.3

Accompanying Duterrau on the long sea voyage were his daughter Miss Sarah Jane and sister-in-law Miss Mary Perigal. Packed in the ship’s hull was a collection of work by this ‘artist of very considerable eminence’ who swiftly established a studio in Hobart Town, setting himself up in business as a portrait painter.4 On 18 October 1832 His Excellency, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur (1784-1854) and family paid Duterrau the honour of inspecting his collection of paintings in Campbell-street, ‘an occurrence which we have pleasure to commemorate as the commencement of an era, in which the fine arts will we trust be patronised in Van Diemen’s Land’.5

Benjamin Duterrau The Conciliation, 1840 oil on canvas 121.0 x 170.5 cm Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart

Duterrau soon became a particularly active member and generous patron of the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institution (established in 1827), fully supporting its high ideals and purpose, even becoming a member of its Committee of Management and, in time, one of its very few life members.6 A catalogue of the Library of the Van Diemen’s Land Mechanics’ Institution, printed in Hobart Town in 1839, indicates that Duterrau had donated five items to the Institution which included a: ‘Portrait of himself (painted by himself)’.7

Provenance details for the 1835 Duterrau self-portrait published by Christie’s in 1974 relay that the canvas was ‘acquired directly from the artist in payment of an account’, the then owner being of the family said to be the first Hobart bakers.8 Might this 1835 canvas be the self-portrait donated by its maker toward the ‘nucleus of a museum in existence’ within the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institution?9 It would have exited the collection of the Mechanics’ Institution when the sale of its entire property, comprising ‘many valuable philosophical donations’, went under the auctioneer’s hammer in early January 1872, the Institution being from its inception ‘designed to promote useful and scientific knowledge’. It ceased to function late in 1871 due to ‘inanition’.10 No catalogue of the auction seems to have survived but certainly on offer, apart from the Institution’s valuable Library, was music (printed and manuscript), a magic lantern and slides, geological specimens, a thirty-nine draw cabinet with specimens of shells and dried plants, and: ‘Framed paintings and engravings’.11

On 16 July 1833 Duterrau delivered a lecture ‘on painting, sculpture, and engraving to a very full meeting of the members of the Mechanics’ Institution’.12 It was the first of many lectures that the resident artist presented in the colony. Bernard Smith followed William Moore in pronouncing Duterrau’s July 1833 lecture the first on painting given in Australia.13 Before the year’s end the portraitist had completed a series of ‘remarkably striking portraits’ of some of the Tasmanian Aborigines which earned him approbation, the memorial worth of the important colonial paintings being immediately recognised. The Hobart Town Courier eulogised: ‘Great praise is due to Mr. Duterrau for his thus fixing on canvas which may commemorate and hand down to posterity for hundreds of years to come so close a resemblance in their original appearance and costume a race now all but extinct.’14

Three self-portraits by Duterrau are known today.15 The earliest features Duterrau aged no more than fifty-two for it was exhibited in the summer

Benjamin Duterrau Portrait of an Artist (Self Portrait), c.1819 oil on canvas 76.7 x 64.2 cm Private collection Benjamin Duterrau Self Portrait, 1837 oil on canvas on composition board 91.5 x 72.0 cm Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart

Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art in London in 1819.16 Long-time resident of Hobart, accountant Mr Lorenzo Lodge (1823-1911) – son of a London architect – presented the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) with a different self-portrait by Duterrau in 1900. He and Duterrau never met as Lodge did not arrive in Tasmania until 1854, three or so years after Duterrau’s death in his Bathurst Street house on 11 July 1851, aged eighty-four. The two men shared a strong belief in temperance, Duterrau lecturing at least twice on the topic of total abstinence in Hobart Town, once in 1847 in the Infant School in Murray Street.17

Mary Perigal – Duterrau’s sister-in-law who kept house for Duterrau and his daughter – died in Lodge’s residence in Sandy Bay in May 1871. She bequeathed her household furniture and effects to Lodge.18 It is most likely, therefore, that the TMAG Duterrau self-portrait was once the property of Mary Perigal having passed to her from Duterrau. It is unlikely to represent Duterrau as he appeared in 1837 which is the year painted on the folio prominently displayed to viewers by the gentleman sitter. Duterrau is clearly portrayed as an older man in the initialled and dated 1835 closely related self-portrait. As he arrived in Van Diemen’s Land aged sixty-five, it is reasonable to deduce that the TMAG selfportrait predates the 1835 version. The full date on the TMAG self-portrait, at the bottom right of the folio is: ‘13 Sep 1837’. This was the day on which Duterrau delivered a lecture to the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institution. It was ‘most respectably attended, both in point of fashion and numbers’. Present in the audience listening to Duterrau expiate ‘on the importance of good taste being encouraged, in the fine arts’, was the cream of the Island’s European gentry, including the Lt-Governor Sir John Franklin (1786 – 1847) and wife Lady Jane (1791 – 1875), Franklin’s Private Secretary Captain Alexander Maconochie (1787 – 1860) and wife Mary, and the young aide-de-camp Henry George Elliot (1817 – 1907). 1837 was the year in which Duterrau advertised having completed a series of paintings representing ‘the occupations and amusements of the Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land’. In the series was ‘a work of such magnitude as the national picture’.19 Duterrau illustrated the lecture pointing to the recent history of painting and engraving in England.20 He knew his subject well having worked as an engraver in England where he was also known to the Franklins.

21

The self-portrait that bears the specific date of an 1837 lecture – evidently so important to Duterrau – measures ‘91.5 x 72 cm’. It has been laid onto Masonite panel; the oil on canvas does not extend

After Raphael (1483 - 1520) The School of Athens, early 17th century oil on canvas 170.4 x 234.0 cm Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

beyond the recto surface of the composition board.22 As such the canvas that initially would have curled around a stretcher has been cut. Is it possible that the TMAG self-portrait was larger when first painted?

The 1835 self-portrait measures 95.5 x 82.5 cm. By comparison, the TMAG version of the painting is about four centimetres shorter in height and about ten centimetres less in width. When included, it was customary for Duterrau to place the year of his production to the right of his initials, such a year being absent in the TMAG version which, upon a sight inspection of the painting, has the bottom half of the initials missing in the lower right corner. Visible, on the table, at the right edge of both paintings, is the entire spectacle case of the subject.

Whilst being on an old re-lined canvas the original canvas of the 1835 self-portrait reaches mostly to the front edge of an old timber stretcher, in some places wrapping a little around it. Considering the age appearance of Duterrau in the 1835 self-portrait we can conclude that it was definitely painted in Tasmania. Given the specific date on the folio of the TMAG’s Duterrau self-portrait it was certainly finalised by the artist in Tasmania noting the important ‘13 Sep 1837’ evening lecture date after the event. Nearly all of the front of the dog-eared, blue-grey folio as held by the sitter – enclosing within loose works on paper – is visible in the 1835 version, the folio being a key element on each of the three self-portraits. In the painting exhibited in 1819 a thick folio is clearly claimed, tucked under the subject’s arm, announcing no title that would point to anything specific regarding its contents, or owner. The TMAG self-portrait folio bears the title: ‘Rafaelle’s / Cartoons’, and, in smaller letters underneath – as a subtitle and perhaps as a final addition like its date – the fainter ‘and School of Athens’. With more balanced spacing and even lettering, prominence is given to the full title on the folio of the 1835 self-portrait: ‘Raffaelle’s Cartoons / and / School of Athens.’ (note Duterrau’s different spellings of ‘Rafaelle’ and ‘Raffaelle’, respectively).

1835 was a tremendously significant year in the colonial career of Duterrau. He delivered four lectures on ‘Sculpture and Painting’ in the 1835 Course of Lectures season of the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institution.23 In its promotion of Duterrau’s first lecture of 1835 The Hobart Town Courier offered:

On Tuesday the 2nd of June Mr. Duterrau will deliver his first lecture on the Fine Arts, and the advantage of the arts and sciences in general as they tend to our happiness, plan of conduct, and our search of

truth. – The school of Athens, explained as it bears a similitude with all institutions established to spread useful knowledge. – The properties of a good picture explained as relates to composition, colouring, &c. particularly drawing as it is connected with perspective and anatomy.

24

Three days after the lecture was delivered the same newspaper reported at length how the speaker had enlarged upon ‘the advantages we might derive in this remote corner of the world from cultivating good taste … – the principle of honour and beauty of truth. As a powerful and instructive example he [Duterrau] analysed that splendid picture of Raphael, ‘The School of Athens.’ In pointing out the characteristics of a good picture the lecturer ‘showed the necessity of attending to graceful attitudes in the figures – to grouping and propriety of arrangement or composition’.25

Duterrau’s colonial production – to represent and group people properly – went hand-in-glove with contemporary British principles of taste that were shaped by British views concerning history painting and British theories of moral sentiment, particularly stemming from Scottish Enlightenment thought.26 In his representations of Tasmanian Aborigines he adhered to expressions that were in keeping with the principles of expression as embodied in Raphael’s Cartoons – (full scale designs for tapestries to cover the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palace, Rome, depicting the Acts of the apostles St Peter and St Paul) – specifically to promulgate moral, philosophical and aesthetic ideas within a colonial context.27

His second lecture for the season was delivered on 21 July 1835. Six days earlier ‘AN OUTLINE of a proposed National Picture, in commemoration of the Aborigines of this Island …’ was published; the etching is said to be the first produced in Australia. It included the inscription: ‘Design’d etch’d & publish’d by Bn. Duterrau July 15th 1835 Hobart Town’.28 Representing a group of people, the Outline was to form the basis of the first major history painting in Australia: The Conciliation, the work dated 1840 in the TMAG being, according to a verso label: ‘A sketch for a national picture / to be 14 feet long by 10 feet high’.29 The first known report about the proposed ‘national picture’ appeared in The Hobart Town Courier in April 1835.30 Six ‘outlines of Aboriginal subjects’, designed and etched by Duterrau, were subsequently published by the artist on 24 August 1835.31 Might Duterrau have produced a folio set of engravings in England after the Raphael Cartoons and/or engraved a print of Raphael’s The School of Athens with its pivotal theme of philosophy?32 He certainly used an image of Raphael’s famous High Renaissance fresco in the Apostolic Palace in Rome to illustrate his 29 June 1849 lecture entitled: ‘The School of Athens, as it assimilates with the Mechanics’ Institution’, the published talk clearly indicating that the speaker intimately knew the oil on canvas copy (after Raphael’s fresco) The School of Athens bequeathed to Oxford University by politician Mr Francis Page (17261803). Received by the University in 1804 the Oxford copy was put on display in the Bodleian Library where Duterrau carefully studied it.33

Duterrau also knew the slim publication The history of the celebrated painting, in the Picture Gallery, Oxford; called “The School of Athens:” supposed to be painted by Julio Romano – first published in 1805 – as he incorporated parts of it in his 29 June 1849 lecture. The text of this anonymous pamphlet was appended to editions of the ‘Oxford Guide’ in the 1820s of which there were numerous editions.34 Such was the importance that Duterrau placed upon the Raphael fresco and the Oxford copy of it that he believed if a print of ‘The School of Athens’ could be seen in a conspicuous part of the Mechanics’ Institution in Hobart Town, a ‘beneficial result would accrue’ in the minds of its colonial viewers, the copy being equally efficacious as the original to teach desirable high ideals for the benefit of the colony. Fine art to Duterrau held nothing short of the miracle power to civilise.35

Benjamin Duterrau’s 1835 self-portrait is arguably the most significant self-portrait in Australia’s early colonial art, the gentleman artist presenting an unambiguous declaration of the important visual sources that guided him in the formation of the self, his art making and his hopes for the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institution. He wanted the humble ‘School’ of learning to be ‘actively instrumental in conveying every noble, useful and enviable attainment that raises the mental character to its highest order of human perfection.’ This was the emigrant artist’s high-minded dream for the entire population of the colony, convict, indigenous people and free settler alike.

PAUL PAFFEN

ENDNOTES For the endnotes to this essay please see the online catalogue at www.deutscherandhackett.com

(1870 – 1947, New Zealand) MEMORIES, ENA TE PAPATAHI, A CHIEFTAINESS OF THE NGAPUHI TRIBE, 1910 oil on panel 20.5 x 14.5 cm signed and dated lower right: – C F Goldie. / 1910 inscribed with title on handwritten label attached verso: Memories. / Ena Te Papatahi. / a chieftainess of the Ngapuhi Tribe / by C. F. Goldie. original artist’s frame

ESTIMATE: $150,000 – 200,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection Leonard Joel, Melbourne, 16 November 1972, lot 169 Private collection, Adelaide Thence by descent Private collection, Adelaide

EXHIBITED

Thirtieth Annual Exhibition, Canterbury Society of Arts, Christchurch, 17 March 1910, cat. 191 Thirty–fourth Annual Exhibition, Auckland Society of Arts, Auckland, 20 – 29 May 1915, cat. 148

RELATED WORKS

The memory of what has been and never more will be [Ina Te Papatahi, Ngã Puhi], 1905, oil on canvas, 115.0 x 90.0 cm, in the collection of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand Forty Winks, 1915, oil on canvas, 62.5 x 75.5cm, private collection

Charles Frederick Goldie Forty winks, 1915 oil on canvas 62.5 x 75.5cm

Memories: Ena Te Papatahi, 1910, is a fine example of the paintings by Auckland artist Charles Frederick Goldie (1870 – 1947) who specialised in the detailed portrayal of sitters chosen to represent what he called the ‘old Maori who in a very short time will be a thing of the past.’1 Goldie began painting these works on his return to Auckland after four years study in Paris where he attended Julian’s Academy from 1893 until 1898. There he studied under famous academic artists like William Bouguereau from whom he learnt a style of oil painting that involved a high degree of skill in drawing and painting the human figure in a naturalistic way with an emphasis on modelling, and illusionistic texture. It was a studio-based practice requiring the use of posed models and controlled lighting. Detail and verisimilitude were essential so that the close-up view was favoured.

With Goldie, as in Memories, it is almost always a one-on-one encounter with the sitter. We experience the intimacy of being able to almost reach out and touch his subjects, for the tactile is the essence of his art. He had a passionate involvement with his artistic mission and was remarkable for his single-minded focus on one type of work. He painted almost nothing else for his entire career but portraits of old-time Maori. At an early stage of his career, it was remarked how he returned again and again to the same sitters. This was especially true of Ena Te Papatahi who sat for Memories. A critic for The Auckland Star in 1905 remarked that ‘...the well-known chieftainess ... sat for two pictures this year, as well as two the year before and two before that.’2 Undeterred he continued to paint her, even showing her controversially as if in death in The Last Sleep (location unknown). In all, he painted her some twenty times.

The pragmatic reason for her popularity with Goldie was given by the Auckland Star critic as her ready availability. Although Goldie presents her in Memories as seemingly living in a traditional Maori village, she did in fact live in the Waipapa Maori Hostel in Mechanics Bay, Auckland, a short walk from Goldie’s Hobson Street studio. The Hostel was a facility in Auckland where Maori who had difficulty finding accommodation in town could stay for free with their own people. Ena stayed there for years with a friend who also posed for Goldie. Ena was able to go to Goldie’s studio and get regular work for which he paid

her. This was exactly the arrangement painters living in Rome or Paris had when hiring exotic models to pose for their compositions. Goldie was not interested in Ena simply as a subject for a portrait. She could be a vehicle for projecting the melancholic mood he wanted to show at the passing of traditional Maori lifestyle and values. Her age, her chin tattoo (moko kauae) and her dignified bearing as a chieftainess matched his requirements. Also, she was willing to pose and to be dressed by the artist, as in this case, in a cloak (korowai) with black tassels, with a tiki carved in greenstone (pounamu) hung around her neck and an ear pendant, also of greenstone, visible on her shoulder. The inclusion of carved Maori figures in the whare (house) behind her and the paddle evoke a traditional setting, not that of urban Auckland.

What Goldie has done is transform Ena into his symbolic image of an old Maori chieftainess lost in recollections of earlier pre-colonial times. The title Memories captures that idea succinctly. In another, larger painting of Ena in the Dunedin Art Gallery the title is expanded to ‘The memory of what has been and never more will be.’ Ena appears to have been a likeable character with a keen sense of humour who wore European dress and smoked a pipe. On occasion Goldie showed her this way. While Goldie did not have great imaginative ability, he did have a commitment to conveying ideas and feelings through the mood of his paintings. At times he could be humorous as well as sad and nostalgic. He was not just a literal recorder of what was before him but an interpreter of the Maori at a time of great change. There is nothing to suggest that he had a deep knowledge of Maori language and culture. He did not speak Te Reo, Maori language, nor did he have engagement with their society. He was in many respects an outsider, but he took his art seriously and captured much of the dignity (mana) of his sitters in his paintings which are prized today by modern Maori as a treasure (taonga) to be handed down to future generations. He painted both male and female sitters favouring those who were older and had the traditional tattoo or moko. He rarely painted young women or young men. Memories is an excellent example of Goldie’s smaller works on a wooden panel rather than canvas. It dates to 1910, a time which is regarded as his finest period as a painter. The wood support gave a firm surface for him to build up his textures as seen in the treatment of the grey hair of Ena with heavy impasto to give it a tactile quality. He also evokes the depth of the incisions of her moko, cut by chisel, into the flesh in a painful process. In this instance the painting has a pronounced chiaroscuro in the face with fully half the image in shadow. Ena’s eyes are downcast, and half closed to convey the idea of introversion and thought rather than awareness of or engagement with the viewer. In another work called Forty Winks, 1915 (private collection) he shows Ena asleep in her own dream world. Goldie was an admirer of Rembrandt whose studies of elderly sitters such as his Woman in Prayer, known in various versions, use the same effects of chiaroscuro and selfabsorption to convey a mood that leads from the literal to the spiritual. This dimension sets Goldie apart from his most well-known rival in the depiction of Maori, Gottfried Lindauer (1839 – 1926).3 Lindauer made extensive use of photographs and gives a wooden, objective recording of features and artefacts suitable for a museum display. Goldie aims at a more human recording of feeling and gives a greater sense of reality to his portraits by his technical skill and illusionism. For example, the way he shows the tiki half hidden by the cloak gives an informality to the item and does not emphasize its ethnographic value. Although small, Memories bestows a dignity and grandeur to Ena Te Papatahi that befits the subject who was descended from prominent Nga Puhi rangatira (chiefs).

1. Goldie to Alfred Hill, 23 Oct. 1916. Hill Correspondence, vol. 2, pp. 285 – 87,

Mitchell Library, Sydney. 2. See Blackley, R., Goldie, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, 1997, pp. 22 – 25, with full bibliography. 3. See Gottfried Lindauer’s New Zealand: The Maori Portraits, Auckland Art Gallery,

Auckland, 2016.